Abstract

Recently, more and more research has examined sustainability reports, including how to process materiality analysis in sustainability reports. However, the motivation for why and how companies prepare materiality analysis has not received much attention from researchers. This study fills a gap in the sustainability literature related to materiality analysis by identifying the theoretical motivations of companies in conducting materiality analysis. The literature review on materiality analysis also showed that the existing measurements have not used the GRI 102-46 and 102-47, which are guidelines for companies in conducting materiality analysis based on the GRI. Therefore, this study developed a measurement of materiality analysis based on GRI 102-46 and 102-47. This study aimed to assess materiality analysis in sustainability reports based on the perspectives of legitimacy theory and stakeholder theory. The research sample was 150 sustainability reports of company listed on the Indonesia Stock Exchange from 2018 to 2020. The researcher developed an index using the GRI approach to measure the quality of materiality analysis. This study proves that the legitimacy theory perspective is mainly the basis for the company in conducting materiality analysis. This study also found no significant improvement in the quality of materiality topic analysis from 2018 to 2020. Of the four financial characteristics, only DER has a significant relationship with materiality analysis, which indicates that the disclosure of materiality analysis tends to be related to the company’s debt condition. The study fills a gap in the literature by contributing to research on sustainability reporting quality, specifically on materiality analysis.

1. Introduction

Increased awareness of stakeholder groups causes companies to face various reporting demands. In response to this demand, there has been an increase in company reports over the last decade [1]. One of the reports that many parties demand is a sustainability report. Although more and more companies are compiling sustainability reports, many parties still criticize because the quality and credibility of the information are still questionable. Even the reports that have received assurance are no exception.

The reasons for this criticism are manifold: due to the limited and voluntary nature of reporting [2,3], regulations that are still evolving [4], and incomplete standardization [5]. It is also due to the vulnerability to manipulation through the narrative character of the report [6,7] or the lax management policy in selecting the reported content [8].

Sustainability reports should present data based on material topics for the company and its stakeholders. Before identifying material topics, the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) encourages companies to conduct a materiality analysis. Material analysis is the process of determining topics that are considered significant based on economic, environmental, and social impacts and substantially affect stakeholder assessments and decisions [9]. According to ref. [10], materiality is concerned with identifying and prioritizing the most relevant sustainability topics, taking into account the impact of each topic on the organization and its stakeholders. This analysis confirms that material issues are recognized and the company publishes a high-quality sustainability report. Materiality analysis helps improve the quality of sustainability reports. This assessment ensures that material issues are recognized and the company publishes a high-quality sustainability report. The materiality analysis identifies material issues for the company and its stakeholders (i.e., economic, social, and environmental issues) [9].

Materiality analysis allows companies to determine report content in a structured manner to confirm the report addresses relevant topics and aspects with relevant stakeholders [10,11,12]. The Global Reporting Initiative (G.R.I.) defines inclusivity and stakeholder materiality as two reporting principles. It requires companies to improve the quality of reporting through information about materiality analysis [9].

The GRI standard presents a materiality matrix to identify relevant topics from the relevant stakeholders. According to ref. [13], identifying material topics to determine the content of the sustainability report will impact the sustainability report’s quality. Ref. [14] stated that determining materiality reflects the process of management’s decision to publish specific information. They argued that firms may use the concept of materiality to exclude negative information. At the same time, ref. [11] asserted that the company could improve transparency to relevant stakeholders through materiality analysis.

In 2013, KPMG’s research found of the 250 largest companies reporting “materiality” in their Sustainability Report, only 59% described the process of conducting a “materiality” analysis. The same thing is still being discovered four years later. The company has not explained the materiality analysis process [9]. Several studies observe materiality topics in sustainability reports by identifying determinants of materiality disclosure [15,16,17,18]. Their research aims to assess whether disclosure of materiality analysis improves reporting.

However, some gaps have not been explained in previous empirical studies regarding theoretical perspectives that can help explain the motives for disclosing material information, which can help increase the report’s credibility. The motivation of companies to compile sustainability reports that are still voluntary can be observed through two theories. Based on the legitimacy theory perspective, companies use sustainability reports to justify their activities to the public as the legitimacy of company activities [19]. Based on stakeholder theory, sustainability reports are not always intended for all interests but certain individual interest groups determined by the company. In this case, the sustainability report is a means of accountability to the company’s stakeholders, sometimes even based on, according to ref. [20], pressure from specific stakeholders.

The company’s reporting on topics relevant to critical stakeholders only is an instrument in stakeholder theory’s (managerial) branch. Companies tend to provide a detailed description of their materiality analysis if stakeholders are their primary target [19]. Meanwhile, if the company seeks legitimacy by utilizing sustainability reports, the topics reported tend to be influenced by the company’s choices addressed to the broader community. They tend to ignore specific stakeholders. Therefore, in the legitimacy theory perspective, companies tend to provide a simple and limited explanation of materiality analysis.

This study fills a gap in the sustainability literature related to materiality analysis by identifying the theoretical motivations of companies in conducting materiality analysis. The literature review on materiality analysis also showed that the existing measurements have not used the GRI 102-46 and 102-47, which are guidelines for companies in conducting materiality analysis based on the GRI. Therefore, this study developed a measurement of materiality analysis based on GRI 102-46 and 102-47.

To date, sustainability reports are still voluntary in Indonesia. However, recently there has been an increase in the number of sustainability reports published by public companies, specifically since the government launched the sustainable development goals in 2017. Therefore, this study analyzed sustainability reports published from 2018 to 2020. The increasing number of public companies that compile sustainability reports shows that companies want to convey their sustainability performance to the public. However, the existing literature has not answered why companies compile sustainability reports based on a theoretical perspective.

Based on the previous literature, research on materiality analysis in sustainability reports in Indonesia is relatively unexplored. So far, research on the disclosure of materiality of non-financial information has focused on Europe and other Western countries [20,21,22]. Ref. [13] highlighted that materiality research is still not widely explored. This research aimed to fill the research gap by using empirical evidence to examine materiality analysis in sustainability reporting on public companies in Indonesia. The following research problems will answer the theoretical background of the company in conducting materiality analysis.

- RQ1.

- How do companies in Indonesia report their materiality analysis?

- RQ2.

- What is the relationship between disclosure of materiality analysis and financial company characteristics?

Using legitimacy and stakeholder (managerial) theories, both research problems are discussed. Using a content analysis approach, this study assessed 150 sustainability reports from companies listed on the Indonesia Stock Exchange from 2018 to 2020.

According to ref. [16], in the perspective of legitimacy theory, companies tend to choose topics related to their reputation and pay less attention to the interests of stakeholders; as a consequence, management will disclose brief and unclear information about materiality analysis. However, if a company seeks to improve the quality of its reporting, the materiality analysis process should be more understandable to stakeholder groups. This practice means that the materiality analysis aligns with the stakeholder theory perspective [16,18].

Therefore, this research has two main contributions; the first is to provide an overview of the theoretical reasons of stakeholder and legitimacy theory regarding the differences in the company’s materiality analysis process. For this reason, researchers should develop an alternative measurement of materiality analysis based on GRI 102-46 and 102-47. Furthermore, this study identified the relationship between the company’s financial characteristics as measured by profitability (ROA and ROE), liquidity (DER.), and company size (Total Assets). Some previous research has not succeeded in proving any consistent findings.

Furthermore, this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 discusses the literature review, which contains the theory of legitimacy and stakeholders and its relation to the concept of materiality. Section 3 discusses previous research and development of disclosure measures of materiality. Following the research methods in Section 4, section five presents the results and discussion. The last section presents the conclusions of the study.

2. Literature Review

According to GRI, sustainability reports are a means to “understand and manage the impact of sustainable development on an organization’s activities and strategies” [11]. All parties should be able to evaluate the company’s contribution to the achievement of sustainable development goals. Sustainability reports must be of high quality by reporting on material topics for all affected parties to meet this goal.

In sustainability reporting, materiality analysis is how companies determine and prioritize relevant topics through a materiality matrix [1]. All issues or topics from this analysis should be part of the sustainability report. Material topics are important because the relevance of corporate decisions to stakeholders can affect the company’s long-term viability [12].

The concept of materiality originates from the term in financial reporting, and there are several definitions for this concept. The International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) states that information is material if omitting them or misrepresenting them could influence the user in making economic decisions [23].

Due to the broad scope of the materiality concept and the complex determination process, GRI provides guidelines to assist companies in determining materiality topics. In sustainability reporting, materiality is the principle for deciding what topics are relevant to be reported in a sustainability report. Since not all material topics are equally important, it is necessary to emphasize the priority in the report [11].

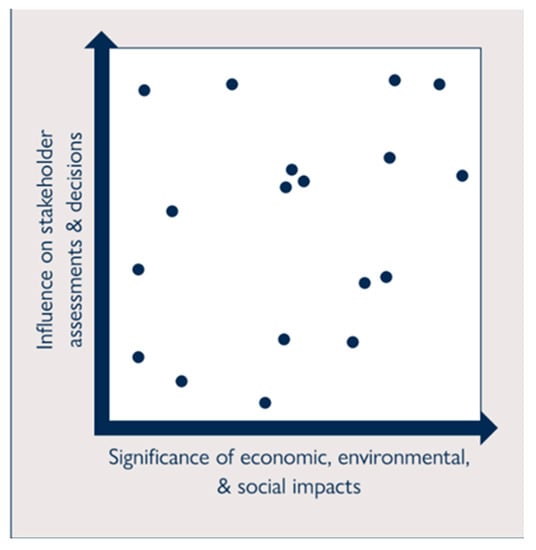

The result of the materiality analysis is a materiality matrix. This matrix reflects the prioritized aspects and topics from the company and stakeholders’ perspectives [1]. Figure 1 shows an example of a material topic analysis using a materiality matrix that describes the company’s priority topics.

Figure 1.

Visual representation of prioritization of topics.

Companies select the most significant material topics regarding their sustainability implications and act accordingly in applying a materiality analysis. If a topic is considered material, then the topic must be explained extensively in the sustainability report, including the allocation of resources and the efforts made by the company [17].

Although standard-setters try to provide more binding content to sustainability reports through the materiality concept, reporting on materiality topics remains voluntary. There is a leeway of choice in this case, which can cause a condition where the quality of reporting will not improve even if the company conducts a materiality analysis.

Because materiality analysis mirrors management decisions, it is interesting to examine and assess management’s perspective in reporting materiality analysis. Whether material topics depend on management decisions and benefit stakeholders, two theories can explain the disclosure of material analysis.

Despite many studies on voluntary reporting, a comprehensive theoretical framework to explain why companies disclose sustainability reporting is still minimal [24,25].

To explain how companies report materiality analysis and identify material topics, researchers usually use stakeholder theory and legitimacy theory. These two theories are built on political-economic assumptions that represent two perspectives that offer insight into phenomena at different levels of resolution [26].

Furthermore, these two theories are used because materiality analysis in sustainability reports will encourage companies to involve and communicate with various stakeholder groups. This action confirms that the company is part of the community system. The survival of companies depends on how they manage relationships with the community [27].

Stakeholder theory suggests organizations pay attention to stakeholders’ interests, i.e., “any group or individual who can influence or be influenced by the achievement of organizational goals” [28]. According to ref. [29], stakeholder theory can examine the extent to which and how companies manage stakeholders.

There are two stakeholder theories: normative and managerial [26,27]. According to normative thinking, companies are accountable to all stakeholders who have the right to know the implications of their operations. This stakeholder theory view is known as stakeholders with ethical values [30].

Meanwhile, the managerial perspective claims that companies use voluntary reporting to manage the most important stakeholders for the company’s sustainability [31]. In stakeholder theory, voluntary reporting manages the company’s primary stakeholders [20]. Ref. [32] asserted that stakeholder theory is about “knowing how” to engage stakeholders and create value for them. A well-conducted materiality analysis will involve stakeholders and provide added value through quality sustainability reports.

Research by ref. [33] proves that the primary reason for providing CSR information is to improve the company’s image and manage critical stakeholder interests. Furthermore, ref. [34] found that broader reporting was given to topics under pressure from specific stakeholders and found variations in report content depending on the key stakeholder interests. Similarly, ref. [35] identified intense pressure from stakeholder groups as a determinant to direct CSR strategy and reporting.

In addition to stakeholder theory, sustainability reports are also often explained through the perspective of legitimacy theory [31,32]. Based on the theory of legitimacy, the company always tries to ensure that its activities do not violate the rules and norms of the surrounding community [36]. Legitimacy theory assumed a “social contract” between a business organization and its respective communities. In legitimacy theory, a community is supposed to be a unit without looking at individuals separately [28,37]. Thus, this theory deals with the relationship between organizations and society. In contrast to stakeholder theory, the purpose of sustainability reports in the perspective of legitimacy theory is the wider community, not just certain groups [20,38,39].

Research by ref. [35] found that companies involved with legitimacy threats have higher narrative disclosure ratios than those that do not. These results indicate that companies provide narrative information to demonstrate commitment to the environment. This disclosure follows the predictions of the legitimacy theory.

Ref. [40] used legitimacy theory to explain the reasons for reducing environmental disclosure in the South African context. They concluded that the goal of legitimacy is achieved by changing and reducing the volume of disclosure. This supports the argument that disclosure in the context of legitimacy is generally limited. As stated by ref. [20], to increase legitimacy, companies try to refrain from disclosing negative or bad news related to the company or even reduce news about social responsibility if it is considered to help increase or maintain the level of company legitimacy. Ref. [39] in his study of voluntary reports (integrated reports), asserts that the purpose of companies compiling voluntary reports is to strengthen their legitimacy in society.

The company’s perspective difference also applies in conducting materiality analysis; as evidenced by ref. [36], there were differences in the materiality identification process in companies. Ref. [36]’s findings show differences in the company’s perspective, which makes the effectiveness and consistency of the materiality analysis different.

Ref. [13] highlighted the concept of materiality in social and environmental disclosures because companies can use it as an excuse not to disclose information that can potentially harm the company. Ref. [13] stated that the precondition for determining undisclosed information is a materiality analysis process. This process indicates management’s choices about what to disclose and what not to disclose in the report.

Ref. [41] argued that materiality significantly influences the formulation and implementation of corporate strategy and risk management processes and is essential in preparing sustainability reports. Ref. [14] concluded that disclosing material topic analysis on sustainability reporting increases organizational transparency.

In addition to discussing the motivation behind why companies compile voluntary reports such as sustainability reports and how to determine the content of sustainability reports, another important thing to pay attention to is how to measure the level of materiality, considering this topic is still in the development stage. Several researchers [17,18,40,42] used various measures to determine an adequate materiality level. From several materiality analysis measurements used in previous studies, refs. [17,42] developed a measure based on the Sustainability Accounting Standard Board (SASB) and the International Integrated Reporting Committee (IIRC). Ref. [17] found that companies that rank well on sustainability materials significantly outperform companies that rank poorly on this topic. In contrast, companies that rank well on the issue of immaterial sustainability do not significantly outperform companies that rank poorly on the same topic. Ref. [17], regarding material and immaterial topics, referred to the materiality map issued by the SASB.

Ref. [42] identified the factors for materiality analysis in the integrated report. They found that the quality of material disclosure (M.D.Q.) was positively related to the effects of learning, gender diversity, and assurance of non-financial information in integrated reports. To measure the quality of material disclosures, they used a seven-component score based on the IIRC.

In addition to developing measurements based on the SASB and IIRC standards, some researchers use measurements based on categories 0–5 [18,40,43]. The study by ref. [18] evaluated the level of materiality disclosure analysis on companies in the Gulf Cooperation Council and its determinants. Their materiality analysis developed a rating from 0 (no information) to 5 (comprehensive disclosure) to measure the disclosure level.

Ref. [40] examined the factors that influence the materiality disclosure of companies in Malaysia. They found that board size, company size, profitability, and industry are insignificant in disclosing materiality in corporate sustainability reports. This study applied materiality and disclosure based on the index developed [44] to measure materiality disclosure. Ref. [44] developed a measure ranging from 0 (no materiality) to 5 (significant materiality).

Furthermore, ref. [43] examined the factors influencing materiality disclosure in the integrated report. They found that the industry, board size, and diversity were significant factors in disclosing materiality in the integrated report. Disclosure of materiality is gauged by two constructs, namely weight and relevance. The materiality weight is gauged by the number of materiality words in the sustainability report. The relevance of materiality is measured in categories 0–5. Although using the same category (0–5), the context and description of the categories in each of these studies are different. From various studies on materiality analysis, this research identified two research gaps that need further exploration. First, there is no measurement of materiality analysis that can simultaneously identify management’s motivation in conducting materiality analysis based on the views of the two theories, stakeholders, and legitimacy. Second, the various measures used in previous studies have not implemented the concept of materiality based on GRI 102-46 and 102-47. GRI 102-46 and 102-47 are the main requirements according to GRI standards in conducting materiality analysis to maintain the quality of sustainability reports. Considering, in general, companies in Indonesia use the GRI standards in preparing sustainability reports, the researchers consider it necessary to develop a measurement of materiality analysis based on GRI guidelines.

This study adopted ref. [43]’s approach linked to the GRI materiality guidelines to determine whether a company uses a stakeholder managerial theory perspective or a legitimacy strategy in a sustainability report. Based on ref. [32], companies that adhere to legitimacy theory tend to make short and fuzzy materiality analysis disclosures, not explaining the methods and processes. Meanwhile, managers who adhere to stakeholder theory will provide a more detailed materiality analysis according to the needs of priority stakeholders.

GRI provides several guidelines for materiality analysis that companies must carry out. The GRI-G3 Guidelines are guidelines that include fairly detailed materiality considerations. They are guidelines for determining whether a particular topic is material enough to be presented in a sustainability report [15].

Based on GRI 102-46 and 102-47, there are several provisions in conducting materiality analysis. First, the company needs to explain the process in determining the topic and content of the report. Determination of material topics will decide what should be reported in the sustainability report. A sufficient explanation should be provided to ensure that the topics disclosed are related to the company’s impact on stakeholders. Second, according to G.R.I., the company must meet principles in compiling a sustainability report. How the company applies this principle in determining the report’s content is also an important part that must be presented. Furthermore, as evidence that the company has carried out a materiality analysis well, the company should present a materiality matrix. This ensures that the material topics are determined based on reporting principles. Finally, the material topics that have been determined are presented as a list of material topics which serve as a guide in preparing the sustainability report. Companies that carry out a good materiality analysis will deliver a quality sustainability report.

3. Research Methods

The object of this research was the sustainability report of companies listed on the Indonesia Stock Exchange. The research population was all companies that prepare sustainability reports. Furthermore, this study explored the implementation of the company’s materiality analysis disclosed in sustainability report.

This study used two sample selection criteria, first, companies that prepare sustainability reports for the period 2018–2020; second, the company conducts a materiality analysis and reports this information in the sustainability report. For this reason, all reports were screened using specific keywords (materiality, materiality analysis). Based on this process, the research sample became 50 companies, so the research observations were 150 company sustainability reports—the sample distributed in the following Table 1.

Table 1.

Research sample.

This study used a content analysis approach in collecting data. Overall, the data collection in the sustainability report is based on a qualitative approach, which is expanded by quantitative analysis steps to answer research questions. The following were the steps of this research: First, collect qualitative data by extracting data from sustainability reports on materiality analysis reporting; second, develop a materiality disclosure index; third, calculate the quality of disclosure of materiality analysis and identify the characteristics of the company based on the theoretical perspective they use.

Analysis of the sustainability report was carried out qualitatively by sorting out information about (a) the process and basis for determining report content and material topic boundaries and (b) explanation of how the organization implements reporting principles to determine report content. Material topic determination should be carried out using the principles of stakeholder inclusivity and materiality. The materiality principle identifies material topics based on the following two dimensions: the importance of the organization’s economic, environmental, and social impacts; and the substantial influence of those impacts on stakeholder assessments and decisions. The following table presents how to calculate the materiality analysis score in this study.

This measurement method follows the methodology in content analysis, which allows qualitative data to be converted into quantitative data systematically and objectively. According to ref. [33], content analysis in reports is carried out by identifying words, sentences, or thematics. This method has been widely used in research that analyses content reports or articles [34,35,36,45,46]. Thus, based on the assessment above, each company will have a maximum score of eight for disclosing its materiality analysis.

Two researchers read the sustainability report on the materiality analysis section to ensure all necessary information and overcome subjectivity. Furthermore, they discussed the conclusions to reach an agreement if there were differences in results. Based on the results of this process, the quality index from the materiality analysis were calculated. Calculation of the quality of materiality analysis refers to Table 2. Based on the disclosures in Table 2, the value of materiality analysis is 0–8.

Table 2.

Measurement of the materiality analysis disclosure.

This study used crosstabulation and chi-square analysis to answer the second research question. The materiality analysis was divided into low (if the value is 5 or lower) and high (if the value is greater than 5). Meanwhile, the characteristics of the companies that are of concern to this research are profitability, leverage, and firm size. These three variables have been used in previous studies and show inconsistent results [18,40,43,44]. Profitability is gauged by both Return on Assets (ROA) and Return on Equity (ROE.); leverage using Debt to Equity Ratio (DER); and company size using total assets. Furthermore, ROA, ROE, and DER are divided into three common categories and have become an agreement in the business world, while total assets are divided into two categories, namely less or equal to 10 trillion Rupiahs and above 10 trillion Rupiahs.

4. Results and Discussion

The presentation of the results is structured as follows: First, it presents a description of the data on the sample companies consisting of material topics of companies based on economic, social, and environmental categories, the method used by the company in determining the material topic, and the company sector. To answer the research question about how companies report their materiality analysis, this study presents the disclosure scores per category. Furthermore, this study used crosstabulation to identify the relationship between company characteristics and materiality analysis.

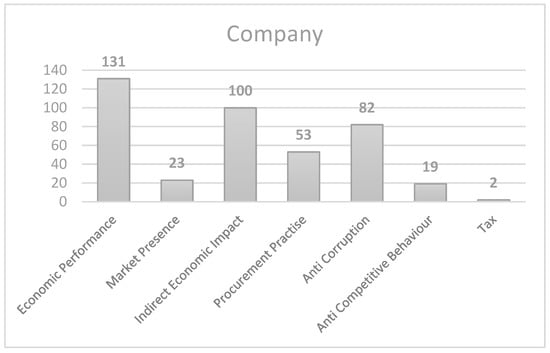

Furthermore, Figure 2 shows the material topics for the economic area of concern to the company. Economic performance and indirect economic impact are the topics most chosen by companies. Economic performance is a material topic for 131 companies, followed by indirect economic impact for 100 companies. The topic of anti-corruption is a topic that is considered necessary by 82 companies. Meanwhile, anti-competitive behavior and market presence are not important material topics for most companies, including tax topics that are only of interest to 2 sample companies.

Figure 2.

Economy topics.

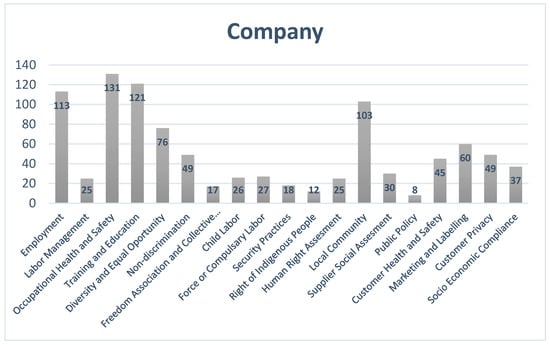

Figure 3 shows topics in the social area which are the company’s material topics. Companies’ top four topics in great demand are occupational health and safety, training and education, and employment and local communities. Meanwhile, less than half of the sample companies disclosed other social topics. Public policy is a material topic that the eight sample companies only disclose.

Figure 3.

Social topics.

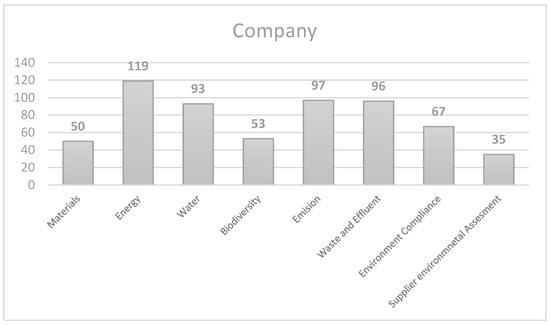

Figure 4 shows the three material topics about the environment disclosed mainly by companies, namely energy, emission, and waste and effluent. Material topics on biodiversity, environmental assessment materials, and suppliers are three topics that have received little attention from the sample companies.

Figure 4.

Environment topics.

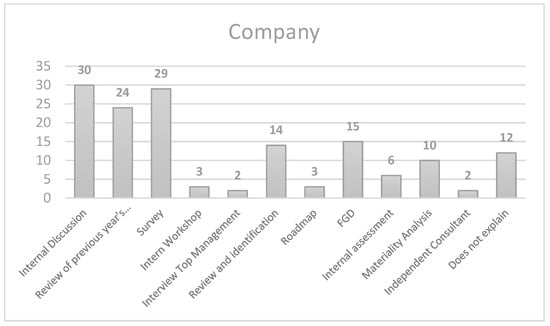

Further analysis identifies how the company determines its material topics. The way the company determines material topics shows how important the company considers the process of deciding material topics for determining the content of the sustainability report. Ref. [13] stated that the materiality analysis process indicates management’s decision to publish certain information. They argued that companies can (intentionally) use the concept of materiality not to disclose negative information. The following Figure 5 describes the methods used by companies in determining materiality topics.

Figure 5.

The method in determining materiality topics.

Of the several methods companies use, most companies use methods that involve more internal parties. These methods include internal discussions, internal workshops, top management interviews, internal assessments, and reviews of the previous year’s topics compared to methods involving stakeholders or parties outside the company, such as surveys. Based on ref. [32], companies that adhere to legitimacy theory will tend to make short and fuzzy materiality analysis disclosures, not explaining the methods and processes in detail and not involving parties outside the company too much.

Next, Table 3 describes the value of disclosure of materiality analysis during the research year.

Table 3.

Materiality analysis disclosure.

Based on Table 3, generally, companies report materiality analysis. However, there are still companies that do not explain the materiality analysis. There are still more companies that make limited disclosures than those that disclose comprehensively. This finding is in line with the research of ref. [13], which found that management chose what to disclose and what not to disclose in the report. Management uses materiality analysis as an excuse not to disclose information that has the potential to be a nuisance to the company. These findings prove that legitimacy theory is still the majority of theories used by companies to analyze materiality topics. To give a little explanation, some companies do not even explain the process of analyzing the materiality topic. This finding could be interpreted as companies’ tendency to consider this process not so necessary. This finding is in line with the research by ref. [41] on the materiality assessment process at the top 10 retailers in United Kingdom. They found that disclosure of materiality assessments in sustainability reports is limited. In addition, the materiality assessment revealed that companies adopt various approaches to assessing materiality. This is in accordance with ref. [36], who found differences in the company’s perspective in preparing materiality analysis. These differences are related to the company’s approach, assumptions, and choices.

Table 3 also shows that most companies (ninety-two) do not implement reporting principles in determining the content of sustainability reports. This finding indicates that the company does not yet understand the principles of sustainable reporting. As a result, sustainability reporting tends to be copying what other companies do. An explanation of how the company has applied the reporting principles to determine report content is what the company should do. This explanation is essential to show the quality of the content of the sustainability report [39]. This finding is in line with research [1] stating that organizations tend not to report approaches in identifying material topics. In the context of sustainability reporting, materiality analysis has the potential to improve the quality of sustainability reports if it is implemented by considering the most significant impact the company has on the environment and society [47]. However, the findings of this study suggest that in current reporting practice, this is rarely the case.

Ref. [17] explained that organizational structures and practices lead to homogeneity. Organizational structures (including their reporting systems) and methods adopted by various organizations tend to be similar to conform to what is considered ‘normal’ by a particular society or group. Organizations that deviate from structures considered ‘normal’ have the potential to have problems gaining or maintaining legitimacy.

In sustainability reporting, materiality is the principle that determines what topics are material enough to be reported. The materiality matrix shows a two-dimensional way of assessing whether an issue is a material, and that a topic can be material based on only one of these dimensions. The use of this exact matrix is not required; however, the existence of this matrix at least shows the company’s seriousness in analyzing the materiality topic. Based on the data in Table 3, point c out of 150 observations, 101 sustainability reports use the materiality matrix to determine the topic. The remaining 49 sustainability reports do not have a materiality matrix. The explanation of the materiality topic analysis is only descriptive and narrative.

The last indicator of materiality analysis quality is a list of materiality topics. A total of 140 companies have a list of materiality topics. Meanwhile, only ten companies did not explain the list of materiality topics. This finding is inconsistent with disclosures 102-47 required by the GRI. This finding is interesting, considering that the company should first explain the list of materiality topics before disclosing the sustainability report’s contents. This finding can be interpreted as there are still companies that do not understand the importance of the process of determining material topics in sustainability reports. The list of materiality topics determines the content of the sustainability report, so if the company does not have a list of material topics, it can be ascertained that the report will not be directed so that the purpose of compiling a sustainability report is not achieved. This causes the quality of sustainability reports to be questioned. This finding is not in line with ref. [9], which stated that the quality of sustainability reports should improve with the materiality analysis.

Table 4 shows an increase in the mean value of the materiality analysis score from 2018 to 2020. However, this increase is not so significant. This value is still below the maximum value [8] expected from the materiality analysis process that the company should carry out. That the maximum value has not been achieved yet indicates that many companies only provide limited explanations about materiality analysis. This proves that the legitimacy theory is the majority motivation for management to conduct materiality analysis. Materiality analysis in sustainability reports is only one of the company’s efforts to ensure that they are considered to function within community ties and norms [33].

Table 4.

Materiality analysis score.

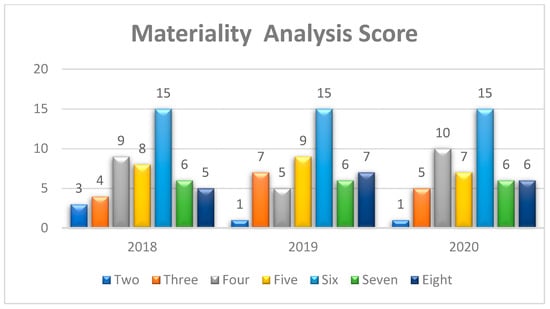

Figure 6 shows the Materiality Analysis disclosure score over the three years of the study. It starts from the lowest (two) to the highest (eight) score. From 2018 to 2020, the most scores obtained were six. There are fifteen samples each year that have a score of six. This value is below the maximum score that should be obtained.

Figure 6.

Materiality analysis score per year.

In 2018, five companies had the highest score (eight). In 2019, there were seven companies; in 2020, only six companies. This finding indicates that from 2018 to 2020, there was no significant improvement in the quality of materiality topic analysis. The importance of materiality analysis carried out correctly and following reporting principles needs to be a concern of the company to ensure the quality of the content of the sustainability report.

Furthermore, this study uses crosstabulation and chi-square analysis to identify the relationship between the company’s financial characteristics and the quality of materiality analysis. The quality of materiality analysis was categorized as low (≤5) and high (>5) to simplify the analysis. The characteristics of the companies identified are Return on Asset (ROA), Return on Equity (ROE), and Debt Equity Ratio (DER). Low ROA values are less or equal to 5 percent, moderate ROA values are above 5 percent to 20 percent, while high values are above 20 percent.

ROE values are grouped according to three categories, low (less/equal to 15 percent), moderate (15–20 percent), and high (more than 20 percent). Meanwhile, DER is categorized as low if it is more than 1, moderate (0.5–1), and high (less than 0.5). This category is based on the generally accepted state of the company’s financial health. A 5% or better ROA is typically considered a good ratio, while 20% or better is considered great [48]. A 15–20% ROE is generally considered good [49]. A good DER is anything lower than 1.0. A ratio of 2.0 or higher is usually considered risky [49]. Although there may be exceptions in some cases for different types of companies, this study assumes that there are no specific differences. Several studies use the same category [50,51].

Table 5 shows that the proportion of companies in the high materiality score is more significant (54 percent) than in the low materiality score (46 percent). In the low ROA category, the proportion of the high materiality score is better (58.4 percent) than in the low materiality score (41.6 percent). Otherwise, in the high ROA category, the low materiality score is higher than the high materiality score.

Table 5.

Crosstabulation ROA and materiality score.

ROA is a value that shows how efficiently the company uses its assets to make a profit. The findings above indicate that companies with low ROA have better materiality analysis. Meanwhile, companies with better ROA tend to have low-quality materiality analysis. This finding can be interpreted as a company that is less able to profit, trying to give a different impression to its stakeholders by compiling a better materiality analysis. However, the Pearson chi-square (0.139 > 0.05) does not prove a relationship between ROA and Materiality score.

Next, Table 6 shows the results of the crosstabulation between ROE and materiality analysis score. ROE is a value that indicates how efficiently the company manages the resources invested by its investors.

Table 6.

Chi-Square Tests.

Table 7 shows that in the Low ROE, high materiality scores are higher (56.4 percent) than low materiality scores (43.6 percent). In contrast, low materiality scores in the ROE high group were higher (60 percent) than high materiality scores (40 percent). This finding is consistent with Table 4. Companies with a smaller ROE tend to disclose materiality analysis better than companies with a more significant ROE. However, the Pearson Chi-Square number at Table 8 did not prove a significant relationship between ROE and Materiality score (0.455 > 0.05). This finding confirms that companies tend to use sustainability reports to change public opinion about companies, especially companies with unfavorable financial conditions [52].

Table 7.

Crosstabulation ROE and materiality score.

Table 8.

Chi-Square tests.

Although there is an argument that profitable companies have better financial resources to publish more material information to their stakeholders, this study did not prove it is significant. The insignificant results were confirmed by previous studies by refs. [53,54,55]. Research by refs. [53,54] concluded that profitability (measured by ROA or ROE) is not a significant predictor of social and environmental disclosure in companies listed in the UK, India, and Italy.

Table 9 shows the crosstabulation between the DER and the materiality analysis score. DER is a ratio that compares the company’s debt with shareholder equity. The higher the DER means the company has higher debt than its equity. This condition is considered less good for the company.

Table 9.

Crosstabulation of DER and materiality score.

Table 9 shows that high materiality scores in the low DER category are higher (61.2 percent) than low materiality scores (38.8 percent). The same is true for the high DER category. This finding indicated that the DER value is not related to the company’s materiality score. Regardless of the DER condition of the company, the company continues to perform a good materiality analysis. This finding is significantly based on the Pearson chi-square (0.004 < 0.05) at Table 10. This finding is in line with ref. [25], which found a significant positive relationship between leverage and the quality of environmental disclosure.

Table 10.

Chi-Square tests.

Table 11 presents the proportion of materiality analysis scores based on company size. Based on Table 11, more companies have low materiality scores in the asset group of less than 10 trillion. While in the asset group of more than 10 trillion, more companies have high materiality scores. This finding can be interpreted as companies with larger sizes performing materiality analysis better. Although this finding is in line with ref. [56], which stated that larger companies are more likely to increase the extent and quality of their sustainability reporting than smaller ones, based on the Pearson Chi-square at Table 12, this relationship is insignificant (0.124 > 0.05).

Table 11.

Crosstabulation size and materiality score.

Table 12.

Chi-Square tests.

5. Conclusions

Materiality analysis is an important process in preparing a sustainability report. Although many researchers have discussed sustainability reports, there is very little empirical evidence about how companies carry out materiality analyses and report them in sustainability reports. This study aimed to assess the disclosure of materiality analysis in sustainability reports based on legitimacy and stakeholder theory perspectives. For this reason, this study developed a materiality analysis measure based on GRI 102-46 and 102-47. This study also identified the relationship between the company’s financial characteristics and materiality analysis.

Answering the first research question, this study found that most companies provide limited explanations about defining report content and topic boundaries and how organizations apply reporting principles to determine report content. Based on findings, it can be concluded that the legitimacy theory’s perspective is the motivation of many companies to conduct materiality analysis. In addition, this study also found that most companies use a materiality matrix in determining material topics. This study also found no significant improvement in the quality of materiality topic analysis from 2018 to 2020.

Concerning the relationship between financial characteristics and materiality analysis, companies with lower ROA and ROE tend to have a better quality of materiality analysis. The explanation for this is that the company is trying to gain legitimacy by presenting better non-financial information (sustainability reports). This finding is in line with the statement [57] that the sustainability report is one of the company’s strategies to attract the attention of stakeholders by displaying non-financial performance. Ref. [39], in their study of voluntary reports (integrated reports), asserted that the purpose of companies compiling voluntary reports is to strengthen their legitimacy in society. This study also found that firms with larger asset sizes tends to perform better on materiality analysis

Of the four financial characteristics, only DER has a significant relationship with materiality analysis. Meanwhile, this study failed to prove that ROA, ROE, and firm size were significantly correlated with materiality analysis. This finding indicates that companies tend to disclose materiality analysis regardless of profitability and size. Once again, these findings confirm that the motivation of materiality analysis is in line with the theory of legitimacy.

The study fills a gap in the literature by contributing to research on sustainability reporting quality, focusing specifically on materiality analysis disclosures. This finding is useful for companies to conduct better materiality analysis to ensure that only material information is presented in the sustainability report.

At the academic level, this research provides empirical evidence of the implementation of legitimacy theory and stakeholders in materiality analysis. Companies with a legitimacy perspective will conduct a materiality analysis that tends to be brief and limited. Meanwhile, companies that use the perspective of stakeholders will conduct a more detailed and comprehensive materiality analysis. Besides that, at the practitioner level, these findings may be helpful for regulators to encourage the implementation of a better materiality analysis to improve the quality of sustainability reports.

This research cannot be separated from several limitations. The number of samples is relatively small due to the limited number of companies in Indonesia that compile sustainability reports. In addition, this study only identified four characteristics of the company’s finances related to the quality of materiality analysis. Future research may consider other company characteristics such as governance and type of industry. Further research can also continue by examining the relationship between the quality of sustainability reports with different motivations (legitimacy and stakeholder theory).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.M.; data curation, S.F.K.; formal analysis, I.M. and S.F.K.; investigation, S.F.K.; methodology, Z.Y. and I.M.; project administration, I.M.; supervision, I.M.; validation, Z.Y. and S.F.K.; visualization, I.M.; writing—original draft, I.M.; writing—review and editing, I.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bellantuono, N.; Pontrandolfo, P.; Scozzi, B. Capturing the Stakeholders’ View in Sustainability Reporting: A Novel Approach. Sustainability 2016, 8, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, B.A.A.; Dias, L.C.P.; Fonseca, A. Transparency of materiality analysis in GRI-based sustainability reports. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 570–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seguí-Mas, E.; Polo-Garrido, F.; Bollas-Araya, H. Sustainability Assurance in Socially-Sensitive Sectors: A Worldwide Analysis of the Financial Services Industry. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2777. Available online: http://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/10/8/2777 (accessed on 11 May 2022). [CrossRef]

- Comyns, B.; Figge, F.; Hahn, T.; Barkemeyer, R. Sustainability reporting: The role of “Search”, “Experience” and “Credence” information. Account. Forum 2013, 37, 231–243. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accfor.2013.04.006 (accessed on 11 May 2022). [CrossRef]

- Braam, G.; Peeters, R. Corporate Sustainability Performance and Assurance on Sustainability Reports: Diffusion of Accounting Practices in the Realm of Sustainable Development. Corp Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 164–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melloni, G.; Caglio, A.; Perego, P. Saying more with less? Disclosure conciseness, completeness and balance in Integrated Reports. J. Account. Public Policy 2017, 36, 220–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meutia, I.; Putra, B.C. Narrative Accounting Practices in Indonesia Companies. Binus Bus. Rev. 2017, 8, 77. Available online: https://journal.binus.ac.id/index.php/BBR/article/view/1944 (accessed on 11 May 2022). [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Milne, M.J.; Gray, R. W(h)ither Ecology? The Triple Bottom Line, the Global Reporting Initiative, and Corporate Sustainability Reporting. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 118, 13–29. Available online: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10551-012-1543-8 (accessed on 11 May 2022). [CrossRef]

- Beske, F.; Haustein, E.; Lorson, P.C. Materiality analysis in sustainability and integrated reports. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2020, 11, 162–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AccountAbility. Accountability 2018 Principles. 2018. Available online: https://www.accountability.org/standards (accessed on 11 May 2022).

- GRI 101: Foundation 2016 101; Global Reporting Initiative. GRI: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016.

- Hsu, C.-W.; Lee, W.-H.; Chao, W.-C. Materiality analysis model in sustainability reporting: A case study at Lite-On Technology Corporation. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 57, 142–151. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0959652613003788 (accessed on 11 May 2022). [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, A.; Costa, R.; Ghiron, N.L.; Menichini, T. Materiality Analysis in Sustainability Reporting: A Method for Making It Work in Practice. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 6, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, R.G.; Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. The Impact of Corporate Sustainability on Organizational Processes and Performance. Manag. Sci. 2014, 60, 2835–2857. Available online: http://pubsonline.informs.org/doi/abs/10.1287/mnsc.2014.1984 (accessed on 11 May 2022). [CrossRef]

- Unerman, J.; Zappettini, F. Incorporating materiality considerations into analyses of absence from sustainability reporting. Soc. Environ. Account. J. 2014, 34, 172–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junior, R.M.; Best, P.J.; Cotter, J. Sustainability Reporting and Assurance: A Historical Analysis on a World-Wide Phenomenon. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 120, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Serafeim, G.; Yoon, A. Corporate Sustainability: First Evidence on Materiality. Account. Rev. 2016, 91, 1697–1724. Available online: http://aaajournals.org/doi/10.2308/accr-51383 (accessed on 11 May 2022). [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.B.; Zaman, R.; Sarraj, D.; Khalid, F. Examining the extent of and drivers for materiality assessment disclosures in sustainability reports. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2021, 12, 965–1002. Available online: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/SAMPJ-04-2020-0113/full/html (accessed on 11 May 2022). [CrossRef]

- Deegan, C. An overview of legitimacy theory as applied within the social and environmental accounting literature. In Sustainability Accounting and Accountability, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Fernando, S.; Lawrence, S. A theoretical framework for CSR practices: Integrating legitimacy theory, stakeholder theory and intitutional work. J. Theor. Account. 2014, 10, 149–178. [Google Scholar]

- Suchman, M.C. Managing Legitimacy: Strategic and Institutional Approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 571–610. Available online: http://journals.aom.org/doi/10.5465/amr.1995.9508080331 (accessed on 11 May 2022). [CrossRef]

- Edgley, C.; Jones, M.J.; Atkins, J. The adoption of the materiality concept in social and environmental reporting assurance: A field study approach. Br. Account. Rev. 2015, 47, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IASB. Conceptual Framework for Financial Reporting At a Glance. IASB. 2018. Available online: https://www.ifrs.org/content/dam/ifrs/publications/pdf-standards/english/2021/issued/part-a/conceptual-framework-for-financial-reporting.pdf (accessed on 11 May 2022).

- Verbeeten, F.H.M.; Gamerschlag, R.; Möller, K. Are CSR disclosures relevant for investors? Empirical evidence from Germany. Manag. Decis. 2016, 54, 1359–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormier, D.; Magnan, M.; Van, B. Environmental disclosure quality in large German companies: Economic incentives, public pressures or institutional conditions? Account. Rev. 2005, 14, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, R.; Walters, D.; Bebbington, J.; Thompson, I. The greening of enterprise: An exploration of the (NON) role of environmental accounting and environmental accountants in organizational change. Crit. Perspect. Account. 1995, 6, 211–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reverte, C. Determinants of Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure Ratings by Spanish Listed Firms. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 88, 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. The Politics of Stakeholder Theory: Some Future Directions. Bus. Ethics Q. 1994, 4, 409–421. Available online: https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/S1052150X00012185/type/journal_article (accessed on 11 May 2022). [CrossRef]

- Kaur, A.; Lodhia, S. Stakeholder engagement in sustainability accounting and reporting: A study of Australian local councils. Account. Audit. Acc. J. 2018, 31, 338–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deegan, C.M. Financial accounting theory Craig Deegan. Account. Forum 2013, 20, 63–73. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, R.K.; Agle, B.R.; Wood, D.J. Toward a Theory of Stakeholder Identification and Salience: Defining the Principle of who and What Really Counts. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1997, 22, 853–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E.; Phillips, R.; Sisodia, R. Tensions in Stakeholder Theory. Bus. Soc. 2020, 59, 213–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belal, A.R.; Owen, D.L. The views of corporate managers on the current state of, and future prospects for, social reporting in Bangladesh: An engagement-based study. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2007, 20, 472–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizul Islam, M.; Deegan, C. Motivations for an organisation within a developing country to report social responsibility information. Account. Audit. Acc. J. 2008, 21, 850–874. Available online: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/09513570810893272/full/html (accessed on 11 May 2022). [CrossRef]

- Deegan, C.; Blomquist, C. Stakeholder influence on corporate reporting: An exploration of the interaction between WWF-Australia and the Australian minerals industry. Account. Organ. Soc. 2006, 31, 343–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deegan, C. Introduction: The legitimising effect of social and environmental disclosures—A theoretical foundation. Account. Audit. Acc. J. 2002, 15, 282–311. Available online: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/09513570210435852/full/html (accessed on 11 May 2022). [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, T.; Preston, L.E. The Stakeholder Theory of the Corporation: Concepts, Evidence, and Implications. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deegan, C.; Rankin, M.; Tobin, J. An examination of the corporate social and environmental disclosures of BHP from 1983–1997. Account. Audit. Acc. J. 2002, 15, 312–343. Available online: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/09513570210435861/full/html (accessed on 11 May 2022). [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M.A. Theoretical insights on integrated reporting. Corp. Commun. An. Int. J. 2018, 23, 567–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Villiers, C.; van Staden, C.J. Can less environmental disclosure have a legitimising effect? Evidence from Africa. Account. Organ. Soc. 2006, 31, 763–781. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0361368206000250 (accessed on 11 May 2022). [CrossRef]

- Belal, A.R.; Cooper, S. The absence of corporate social responsibility reporting in Bangladesh. Crit. Perspect. Acc. 2011, 22, 654–667. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1045235411000311 (accessed on 11 May 2022). [CrossRef]

- Ngu, S.B.; Amran, A. Materiality Disclosure in Sustainability Reporting: Evidence from Malaysia. Asian J. Bus. Account. 2021, 14, 225–252. Available online: https://ajba.um.edu.my/index.php/AJBA/article/view/27452 (accessed on 11 May 2022). [CrossRef]

- Gerwanski, J.; Kordsachia, O.; Velte, P. Determinants of materiality disclosure quality in integrated reporting: Empirical evidence from an international setting. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 750–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasan, M.; Mio, C. Fostering Stakeholder Engagement: The Role of Materiality Disclosure in Integrated Reporting. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 288–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooghiemstra, R. Corporate Communication and Impression Management—New Perspectives Why Companies Engage in Corporate Social Reporting. In Business Challenging Business Ethics: New Instruments for Coping with Diversity in International Business; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2000; pp. 55–68. Available online: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-94-011-4311-0_7 (accessed on 11 May 2022).

- Tilling, M.V. Refinements to Legitimacy Theory in Social and Environmental Accounting not One Theory but Two (at Least); Commerce Research Paper Series; 2004; Available online: https://www.academia.edu/25301128/Refinements_to_Legitimacy_Theory_in_Social_and_Environmental_Accounting (accessed on 11 May 2022).

- Lubinger, M.; Frei, J.; Greiling, D. Assessing the materiality of university G4-sustainability reports. J. Public Budg. Account. Financ. Manag. 2019, 31, 364–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangngisalu, J. Current Ratio, Return on Asset, and Debt-to-Equity-Ratio on Stock-Price of Sector Property and Real Estate. Gold. Ratio Financ. Manag. 2022, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, W.; Li, H.; Ali, R.; Rehman, R.U. Knowledge Mapping of Corporate Financial Performance Research: A Visual Analysis Using Cite Space and Ucinet. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oncioiu, I.; Petrescu, A.-G.; Bîlcan, F.-R.; Petrescu, M.; Popescu, D.-M.; Anghel, E. Corporate Sustainability Reporting and Financial Performance. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyere, M.; Ausloos, M. Corporate governance and firms financial performance in the United Kingdom. Int. J. Financ. Econ. 2021, 26, 1871–1885. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ijfe.1883 (accessed on 11 May 2022). [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.; Comfort, D.; Hillier, D. Materiality in corporate sustainability reporting within UK retailing. J. Public Aff. 2016, 16, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, I. Sustainability and financial performance relationship: International evidence. World J. Entrep. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2021. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shaer, H.; Albitar, K.; Hussainey, K. Creating sustainability reports that matter: An investigation of factors behind the narratives. J. Appl. Account. Res. 2022, 23, 738–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, P.M.; Overell, M.B.; Chapple, L. Environmental Reporting and its Relation to Corporate Environmental Performance. Abacus 2011, 47, 27–60. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1467-6281.2011.00330.x (accessed on 11 May 2022). [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Lozano, M.; De Vicente-Lama, M.; Tirado-Valencia, P.; Cordobés-Madueño, M. The disclosure of the materiality process in sustainability reporting by Spanish state-owned enterprises. Account. Audit. Acc. J. 2022, 35, 385–412. Available online: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/AAAJ-08-2018-3629/full/html (accessed on 11 May 2022). [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Shao, C.; Chen, J. Approaches on the Screening Methods for Materiality in Sustainability Reporting. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3233. Available online: http://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/10/9/3233 (accessed on 11 May 2022). [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).