1. Introduction

Business process management (BPM) is an accepted means to optimize business processes. It has a long tradition in information systems engineering and constitutes a research field of its own [

1,

2]. BPM can be understood as the science and practice both of overseeing how processes are executed to ensure consistent and high quality outcomes and of taking advantage of the improvement opportunities of these processes [

3,

4]. Today, BPM is more and more focusing on ensuring that business processes are sustainable [

5], from not only the environmental perspective (Green BPM) but also that of social sustainability [

6]. While this perspective of sustainable BPM includes a continuous effort, it also implies the execution of BPM projects [

7]. In fact, authors have argued that BPM can be understood as a sequence of recurring projects [

8,

9].

Building on this, project management is understood as one of the core capabilities for successful BPM [

10], especially within the core factor BPM methods [

11]. The BPM handbook builds upon this and argues that for successful BPM, organizations require project management capabilities “that are used for the overall enterprise-wide management of BPM and for specific BPM projects. The latter requires a sound integration of BPM methods with specific project management approaches (e.g., PMBOK [Project Management Body of Knowledge], PRINCE 2)” [

12] (p. 117).

However, the assessment that project management capabilities are important for successful BPM mainly results from the pre-digital era. On the one hand, project management has changed and increasingly follows less waterfall or plan-based approaches, such as PMBOK or PRINCE 2. Instead, modern agile approaches of project management are used [

13]. On the other hand, contemporary BPM studies focus less on project management. For example, project management was no longer mentioned as a capability in the recently updated BPM capability model [

3]. This is also underlined by a recently published measurement instrument for BPM capabilities [

14], where project management is not a capability that is measured. Instead, it can be interpreted as a negative aspect within process-oriented top management commitment, when it is insisted that top managers should focus on BPM as a way of managing the business instead of focusing on individual process improvement projects [

14]. Exaggeratedly, it could be argued that, as BPM is mainly executed as a continuous activity, and as remaining BPM projects are managed in an agile fashion, traditional project management is no longer a capability needed for successful BPM.

With this study, we want to assess whether this exaggerated statement is true. Specifically, we aim to answer the following research questions: In view of digitalization, how important is project management for contemporary BPM? What are the critical aspects of project management for contemporary BPM in the view of digitalization?

To answer the questions, we first discuss prior research on project management capabilities and BPM. We derive four potential explanations for why contemporary BPM, in the view of digitalization, might not view traditional project management knowledge as a core capability (

Section 2). Next, we conduct an in depth case study and identify aspects where project management influenced BPM success (

Section 3 and

Section 4). The results are discussed in light of the existing scholarly literature in

Section 5.

2. Research Background

2.1. Business Process Management

BPM can be understood as the science and practice both of overseeing how processes are executed to ensure consistent and high quality outcomes and of taking advantage of the improvement opportunities of these processes [

3,

4]. There is general agreement that BPM can be understood as a set of organizational capabilities [

8,

9,

10,

12,

14]. The currently most prevalent way of thinking about these BPM capabilities is to structure them into the six core elements of strategic alignment, governance, methods, information technology (IT), culture, and people [

12], a perspective that also holds true in a digitalized world [

3]. The core element of strategic alignment refers to the continuous linkage between organizational priorities and business processes to achieve business goals. Governance encompasses roles, responsibilities, and decision-making processes with regard to processes and process change. Methods includes the approaches and techniques that support and enable consistent actions and outcomes of BPM. The core element of IT refers to the hardware, software, and information systems that enable and support process and process management activities. The core element of people, as a softer factor, includes the individuals and groups who enhance and apply their process-related knowledge and expertise. Last, culture, as another softer factor, includes the collective values and beliefs that shape process-related attitudes and behaviors [

3,

11,

12].

BPM and the corresponding organizational capabilities are used for the radical [

2] and continuous improvement of business processes [

15] and thus inform digitalization efforts. Radical improvement in the tradition of business process reengineering [

2] often refers to discrete change [

16]. In contrast, the continuous activities of BPM are used to either continuously improve processes over time [

15] or to encounter processes at drift [

16,

17]. However, there are strong arguments that “the senior executive team or board of directors [should perceive] process management not as a project but as a way of managing the business” in contemporary, digitalized environments [

14] (p. 310).

From a sustainability perspective, BPM requires both the discrete and the continuous change activities mentioned above. It is clear that organizations need to implement sustainable processes to become sustainable [

5]. As such, sustainable BPM takes sustainability goals into account when changing processes [

6]. As Seidel and Recker highlight, “some processes may become more sustainable through rather simple improvements […] [while] others may require a fundamental redesign” [

7] (p. 251). Here, simple improvements refer to continuous change, while fundamental redesign refers to a discrete change activity.

2.2. Project Management

The term project can be defined as “a temporary endeavor undertaken to create a unique product, service, or result” [

18] (p. 13). Accordingly, project management refers to “the application of knowledge, skills, tools, and techniques to project activities to meet the project requirements” [

18] (p. 10). As such, project management deals with the creation of a new organizational state, e.g., through the creation of a new or adapted product, service, or process. Project management ensures that the creation of this new organizational state happens within the prior defined time and costs, i.e., that the project is completed on time, within budget, and in scope. Sustainable project management extends this perspective and also includes sustainability targets [

19]. The PMBOK defines 10 knowledge areas that a project manager should be knowledgeable in [

18]:

Project Integration Management can be understood as the core project management task. It encompasses all activities to identify, define, combine, unify, and coordinate other project management tasks. It ensures the alignment of project plan, budget, risk management, etc., and includes the management of all project plan changes.

Project Scope Management covers all tasks related to the project scope. This area is especially focused on the delineation of the project, i.e., ensuring that the project includes all (and only) the work required to complete the project successfully.

Project Schedule Management focuses on the time dimension of the project. It includes all activities that ensure that the project is completed on time.

Project Cost Management focuses on the budget dimension of the project. Here, the focus is on planning, estimating, budgeting, funding, managing, and controlling costs so that the project is completed within the approved budget.

Project Quality Management encompasses all tasks that ensure that the project meets quality requirements, especially with regard to the stakeholders’ expectations.

Project Resource Management includes the activities that identify, acquire, and manage the (monetary and non-monetary) resources needed to complete the project.

Project Communications Management deals with the development and execution of a project communication strategy. This communication strategy should be designed to achieve effective information exchange between the different project team members and between the project and stakeholders.

Project Risk Management acknowledges that all projects come with risks. This knowledge area includes all activities that minimize the risks and their impact, e.g., the activities of risk monitoring, response planning, or response implementation.

Project Procurement Management includes the processes necessary to purchase or acquire goods from outside the project team. This knowledge area has a more legal focus than resource management and also encompasses the management of contracts, purchase orders, or service-level agreements.

Project Stakeholder Management forms the last knowledge area. Closely related to project communication management, stakeholder management focuses less on information exchange and more on ensuring the right level of stakeholder engagement.

In the last decades, projects are increasingly executed following agile values and principles, as expressed in the agile manifesto [

13,

20,

21]. Agile values and principles, as a new way of project management, focus on iterations, increments, self-organization, and closer customer interaction and collaboration [

22]. Projects that are managed in an agile way are typically divided into small cycles (or iterations) where smaller parts of the project’s scope are planned and executed [

20,

22]. These parts incrementally add up to the full project scope. However, changes in the project scope are easier to manage as the original project scope has only partially been planned upfront. This work in iterations and increments is only possible if the team is able to self-organize, i.e., take over a lot of the activities mentioned in the knowledge areas above. One of the main goals of agile project management is to create real customer value through a strong focus on true customer interaction and collaboration [

22]. Through this, agile project management also facilitates reaching sustainability goals [

23].

2.3. Project Management as a Business Process Management Capability

For many years, project management was understood as an important prerequisite for or even as a capability of BPM. Prior research showed that process management initiatives often rely on project management capabilities [

24,

25]. Moreover, project management is often seen to be one of the BPM success factors [

9]. Quantitative studies have underlined this understanding: Project management capabilities have a direct positive impact on BPM performance [

10] and also on business process performance [

26]. More prominently, project management was included as one of the capability areas within the BPM core factors in the most prevalent BPM capability model [

11,

12]. Building on this, project management was also found to be one of the core competencies supplied by BPM professionals [

27]. The process management handbook highlights the needed sound integration of project management methods explicitly mentioning the PMBOK [

12].

However, in the last year, the BPM capability model was updated in view of digitalization, partially by the original authors [

3]. To this end, a Delphi study with 29 participants was conducted, first, to highlight the challenges and opportunities of BPM in light of digitalization and, second, to update the capability model with new or adapted BPM capabilities. This updated model includes 30 capability areas. According to the findings, project management is not included as a BPM capability any more. Moreover, the detailed online appendix E also shows that the original project management capability area is, at best, only partially covered by the new capability areas [

3].

In general, there appears to be a shift in perspectives in the last decades.

Table 1 summarizes some core findings with regard to publications on BPM and the corresponding relationship to project management. As indicated, the importance of project management for BPM appears to be declining with increasing digitalization.

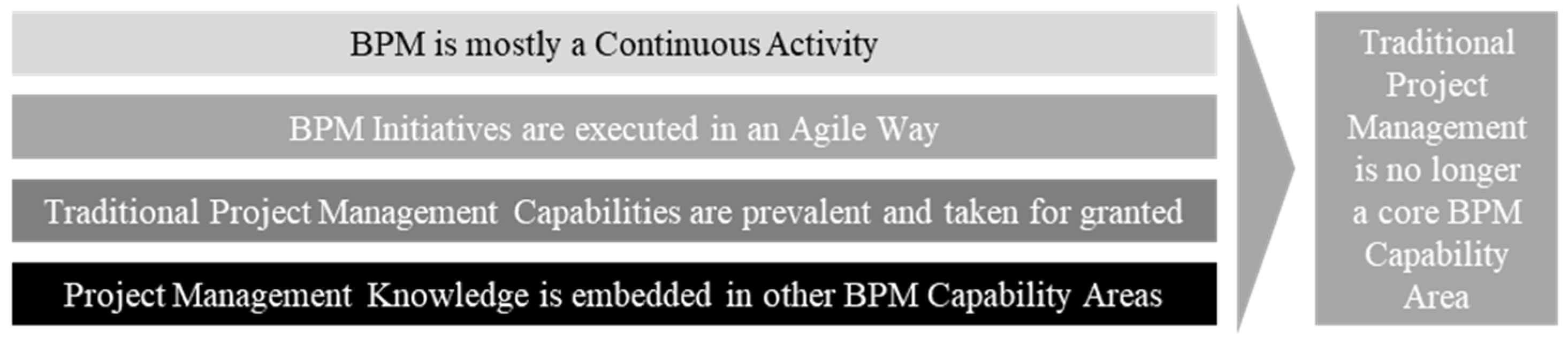

There are four potential reasons for this reduced attention to project management with regard to BPM in the view of digitalization (

Figure 1). First, the prior literature has argued that BPM should be seen as a continuous activity [

28]. Organizations should not rely on BPM projects any more [

14]. It might be that the experts involved by Kerpedzhiev et al. [

3] follow this perception, i.e., they do not consider BPM as a project but as a continuous, routine-like activity. Second, even if BPM is still executed in a project-like fashion, it might be that, following general observations on project management, these BPM projects are increasingly executed in an agile way [

29]. These agile approaches focus less and less on traditional project management capabilities [

13]. As such, traditional project management capabilities have less importance for BPM also. Third, assuming that BPM is executed in a project-like fashion, relying on traditional project management capabilities, it might be that these project management capabilities are now prevalent in organizations and therefore not seen as important by experts any more. Last (and building upon the third reason), several of the project management knowledge areas have their direct equivalent in the BPM core capability areas. For example, the knowledge area “Project Communication Management” has strong overlaps with the capability areas of process customer and stakeholder alignment [

3,

11] and the capability area of change centricity [

3]. It might be that the most important project management knowledge areas are already seen as BPM capabilities on their own, and thus, an overarching project management capability is not needed for BPM success.

3. Research Method

To answer our research questions, we conducted an in-depth case study [

30] at ServiceCo (pseudonymized for confidentiality reasons) as the representative case for the phenomenon of interest. ServiceCo is a German service company active in the healthcare industry. In the past, ServiceCo consolidated its product portfolio and has achieved a strong market position with a good and growing customer base. However, so far, it has not explicitly focused on process efficiency targets.

In 2017, ServiceCo launched a structured process optimization and digitalization initiative with the goal to (a) improve process efficiencies by 20% through optimized and digitalized processes, (b) right-size human resources (reduce full-time equivalents (FTE) by a corresponding 20%), and (c) increase customer satisfaction through higher process digitalization while maintaining the effectiveness of the processes. In this initiative, ServiceCo not only worked on analyzing the existing business processes and improving them, they also used BPM to collect requirements for modern digitalization measures, e.g., core system changes, robotic process automation (RPA), artificial intelligence and machine learning, and customer self-service portals.

We studied ServiceCo over the course of over 3 years (2017–2020) using the participant observation method [

30]. During this time, we had close interactions with multiple key members and stakeholders of the process optimization initiative. These people included both initiative leads, the line head of organizational development, the Chief Information Officer, and multiple business leaders. On an operational level, these also included various operational employees involved in process improvement initiatives. We were able to observe them in their interactions in the initiative on an almost daily basis, create corresponding notes, and collect secondary data. On a more strategic level, we participated in bi-weekly strategy meetings that also included discussions on the current process optimization and digitalization initiative and the way BPM is established at ServiceCo.

After our participating observation, we conducted four formal interviews with key employees, i.e., both leads of the improvement initiative, the head of change management, and a line manager. These interviews lasted about 30 min and were recorded and transcribed (see

Table 2).

With the help of these different data sources, a rich description of BPM at ServiceCo emerged. To answer the research questions, we followed deductive coding [

31]. To this end, a coding frame based on the ten key project management knowledge areas and the identified four key features of agile project management was developed. Here, the codes are formulated according to the theoretical concepts introduced above. During coding, additional sub-codes were added where needed. The codes were reviewed and reinterpreted in light of the prior observations in a hermeneutic circle.

4. Results

Based on the analyzed case data and the personal observations, we could identify direct instances of eight of the ten project management knowledge areas and all four core ideas of agile project management within the case (see

Table 3).

The structured process optimization and digitalization initiative which was started by ServiceCo followed the typical BPM lifecycle [

4]. In so-called “waves” of 3 months, different core processes or connected process bundles were analyzed, redesigned, and implemented. In each wave, multiple process optimization teams were working in parallel. A team was responsible for one of the core processes or process bundles. Each team consisted of different process management professionals both from a central BPM department, the corresponding functional departments (especially the process owner(s)), and (if needed) external process and IT consultants. The teams presented their progress to a steering committee three times: (1) after the analysis of the as-is processes, (2) after the redesign, and (3) during the implementation of the new processes with a defined set of requirements for digitalization.

Next to these waves and the corresponding process optimization teams, an overarching initiative management was instantiated. This initiative management was led by two people, a technical lead from the IT and BPM department and a business lead from a business unit. They were supported by an initiative core team which included the head of organizational development, the head of HR, the CIO, and the head of communications. This core team was jointly working on achieving the overall targets and reported to the steering committee mentioned above.

During the process optimization and digitalization initiative, ServiceCo heavily relied on project management knowledge. As indicated above, the initiative had three integrated goals which were relevant for both the individual process optimization teams and the overarching initiative management. While the process optimization teams managed this scope on a more individual level, the initiative management needed to manage scope on an overarching level using a variety of tools, e.g., a common data share or regular integrating meetings. As such, the initiative relied on project integration management knowledge.

During the initiative, the schedule also needed to be managed on both levels. On the one hand, the individual process optimization teams needed to work to fulfill their three-month schedule in each wave. One the other hand, initiative leadership had to work towards achieving the whole initiative within time. As resources were scarce (see also below), the schedule needed to be extended. To sum up, we could observe project schedule management knowledge to be important for the overall BPM initiative.

In particular, the initiative leadership had to have a close look at costs. While most of the costs occurred for internal employees, the external consultants needed hard budgets. Here, the initiative leadership had to assess and control these costs over the time of the initiative, which required some level of project cost management knowledge. Through this, the initiative stayed within the planned budget with regard to external costs.

With regard to project quality, the initiative leadership and the individual process optimization teams needed to focus on the creation of high-quality solutions. While this had great overlap with the defined scope (especially the required increase in customer satisfaction), quality became especially important in the implementation of digital-enhanced processes. In particular, the introduction of new components used in the initiative (e.g., RPA or advanced optical character recognition) was problematic at the start. Here, project quality needed to be closely managed by the initiative leads.

As indicated above, resources were oftentimes scarce, and the corresponding leaders spent a considerable amount of time on their identification, acquisition, and management. This included external IT consultants and internal process management professionals. Especially in the later waves, initiative leadership needed to acquire new project team members that could be trained to work in the project optimization teams. The success of this resource management in conjunction with schedule extensions prevented situations where process optimization teams were understaffed.

Communication of both the initiative goals and the corresponding changes each process optimization team identified and implemented was one major theme that was intertwined through the whole duration of the initiative. For this reason, the head of communications of ServiceCo was part of the overarching initiative core team. As the head of communication indicated, management of the right messages to be shared within the team and across the boundaries of the initiative was crucial.

Obviously, the process optimization and digitalization initiative came with risks. While initiative leads discussed some of these risks (e.g., resources becoming unavailable, failing introduction of new digitalized processes due to technical problems or organizational non-acceptance, or severe stakeholder protests against the planned FTE reduction), constant risk monitoring or response planning were not observable.

There were only few resources in the process optimization and digitalization initiative that needed to be procured. These included mainly external consultants and a few tools. Most other resources stemmed from the organization and thus did not require any dedicated procurement. However, procuring tools resided with IT, and the procurement of consultants was also handled outside of the initiative. As such, the knowledge area of project procurement management was not observable in the case study.

In contrast, the stakeholders of the project were closely managed. Top management was formally informed by the initiative leads every 3 weeks. The individual process optimization teams presented their progress to a steering committee which also included stakeholders (e.g., from data security and compliance) three times per wave. This ensured consistent top management support for the whole initiative.

Looking at selected core ideas of agile project management, the case also underlines the importance of corresponding skills and capabilities. Each wave can be seen as consisting of three iterations where the process optimization team works on one core process or process bundle. In the first iteration, an understanding of the processes and first ideas for improvement were created. In the second iteration, these ideas were refined into a redesign of the process and requirements for digital solutions. In the third iteration, the redesigned processes were further worked on as they were implemented.

A wave in itself can be understood as an increment. All waves added up incrementally to the overarching target to optimize and digitalize ServiceCo. There was no grand plan for when to optimize which process/process bundle. Instead, based on learnings from earlier waves further waves were planned and replanned, especially taking into account optimizing related processes. As such, the overall initiative profited from prior experiences and consistently improved the used process optimization processes.

While each process optimization team was, to some extent, steered by the central initiative management and the stakeholders, it was, in itself, self-organized and needed to structure optimization activities on its own. The central initiative management set the goals (i.e., defined the “what”), while the team itself needed to plan, schedule, and coordinate self-sufficiently (i.e., defined the “how”).

Last, the whole initiative relied on close interaction with customers, i.e., the business departments and operational employees. They were included in all steps of each wave from idea generation over detailing until implementation. When teams neglected customer collaboration at the beginning, initiative management needed to step in to ensure success in the long term.

Using the identified project management knowledge areas and the core ideas of agile project management, the initiative was fairly successful. Although the schedule needed to be extended, the overarching goals of higher process efficiency, reduced administrative costs, and improved customer satisfaction could be reached. Admittedly, the realization of the identified savings potential will take more time, so a definite assessment of the initiative’s success is not possible as of now.

5. Concluding Discussion

Current research on BPM capabilities puts less emphasis on project management [

3]. However, the results of the presented case study indicate that the success of contemporary process optimization and digitalization initiatives rely on the application of project management knowledge, both from a more traditional, plan-based perspective [

18] and from an agile perspective [

13]. We could find evidence for eight of the ten knowledge areas for project management as defined by the PMBOK. Moreover, we could also find evidence for all four core ideas of agile project management.

These observations form evidence against some of the potential reasons (see

Figure 1) for a declining importance of project management for BPM. First, the analyzed BPM initiative had a clear start and end and, therefore, according to prior definitions, can be considered a project [

18]. As such, the initiative cannot be considered a continuous activity. Apparently, even in light of digitalization, organizations still plan, execute, and control process optimization and digitalization initiatives in a project-like manner. Second, while the studied case of ServiceCo followed the four identified core ideas of agile project management, the overall initiative cannot be considered agile only. Instead, it can be described as following a hybrid project lifecycle [

20]. The case underlined that traditional project management knowledge areas such as scope, schedule, or cost management, are still important for the execution of process optimization and digitalization initiatives. The third potential reason for the declining perceived importance of project management for BPM is that project management knowledge is prevalent in organizations and, thus, taken for granted by the expert panel in [

3]. However, prior studies show that a large share of projects still do not succeed and that, on average, 11.4% of a project budget is wasted due to poor project performance [

32], which can be seen as an indicator of a lack of project management capabilities in contemporary organizations. Thus, the argument that project management capabilities can be taken for granted and do not need to be considered for BPM comes with heavy doubt. The last potential reason can be assessed only partially using the case study results. The results indicate, however, that not all project management knowledge areas are embedded in BPM capability areas. While this might be the case for project communication and stakeholder management, the areas of schedule and cost management appear to have been neglected by the Delphi panel and thus do not appear in the updated BPM capability model [

3].

Based on this, there is no good argument why project management should not be required for BPM. On the one hand, it might be true that project management is not needed when BPM is not executed in a project mode, i.e., neither to counter unconscious change or process drift [

17] nor to continuously monitor and improve processes [

15]. On the other hand, prior research has shown that continuous improvement can culminate in a sequence of recurring BPM projects [

8,

9]. Moreover, instances where real BPM projects are executed exist: The case studied shows that organizations execute process improvement initiatives in a project mode in light of digitalization. The literature also argues that BPM projects are needed to cope with the changes induced by exogenous shocks [

16]. Next to this need for project management capabilities in BPM projects, project management capabilities might also be needed in BPM introduction projects. Prior research has shown that organizations consciously start programs to build BPM capabilities [

8]. It can be safely assumed that these programs are executed in project form and, as such, also require project management capabilities.

From a sustainability perspective, project management skills are needed in all of these situations. Research on sustainable project management has underlined the importance of skills in meeting sustainability targets [

19]. Research on sustainable BPM argued that organizations need to manage their processes to be able to meet sustainability targets [

5,

6,

7].

This study has several implications for theory. First, it could be shown that project management capabilities are needed for (at least some) BPM initiatives. While this finding is in line with earlier research, we contribute the existence of this need also in the view of digitalization. Whether project management should be considered a BPM capability, or whether both fields should be conceptualized as separate but connected, remains an open question which requires further work. Second, we contribute a deeper understanding of agility in the context of BPM [

29] and show that BPM projects follow some of the core ideas of agile project management. Regarding how far agility in BPM really leads to higher success in BPM initiatives is another open question. Third, we contribute a deeper understanding of the specific project management knowledge areas that are required for successful BPM projects. However, this understanding lacks any quantification of the strength of influence of individual knowledge areas on BPM success. Last, we also contribute a better understanding of project management capabilities for sustainable BPM. We were able to show that reaching sustainability targets requires sustainable BPM, which, in turn, requires project management capabilities.

Moreover, our study also has two main lessons learned for practitioners. First, organizations starting a large process optimization and digitalization initiative should include people with the right project management knowledge. Prior research showed that this knowledge is crucial for BPM success [

10], a finding that is also underlined for process digitalization projects by this study. Second, in these process optimization and digitalization initiatives, practitioners should also consider following some aspects of agile methodologies. The case-study organization employed an approach that can be considered hybrid and was quite satisfied with the corresponding results. While our study was based in the healthcare industry, the results should hold true for other service firms and their BPM efforts, too. To sustainably manage processes over a long period of time, project management capabilities are needed to facilitate phases of radical change (i.e., discrete BPM projects), such as those driven by digitalization [

25], exogenous shocks [

16], or by clear sustainability goals [

19].

Naturally, this study comes with some limitations. Most important, the results stem from a single, case study in the German healthcare industry. As such, transferability to other companies, regions, and sectors is limited. Nevertheless, we believe that the case can be considered representative for the phenomenon of interest. Moreover, our assessment of the success of the project optimization and digitalization initiative is limited. Typically, the real and lasting success of such large scale initiatives can only be assessed after several years.

Building on these findings and limitations, future research could quantitatively assess the importance of different project management knowledge areas for BPM success. While our results indicate that eight out of ten knowledge areas are needed, a quantitative analysis would lead to deeper insights into this area. Moreover, future research could also conceptualize agile and hybrid BPM project management in a more detailed way building on the insights into the interplay provided by this article. Next, the interplay of sustainable project management and sustainable BPM can be studied further. Lastly, the transferability of our results to other sectors could also be analyzed using further qualitative studies, such as case studies in other sectors.

To conclude, BPM needs project management capabilities: Our results suggest that knowledge both in traditional and agile project management is needed to sustainably manage business processes. While this is true for discrete BPM projects, it might not be true for continuous BPM efforts, e.g., having process drift under control or continuously improving processes (ad RQ1). A deeper analysis shows two critical aspects (ad RQ2): First, when setting up a process optimization and digitalization initiative, project management knowledge needs to be considered. Second, organizations should also extend their BPM project methodologies more towards agility.