How Is Alumni Giving Affected by Satisfactory Campus Experience? Analysis of an Industry-Research-Oriented University in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

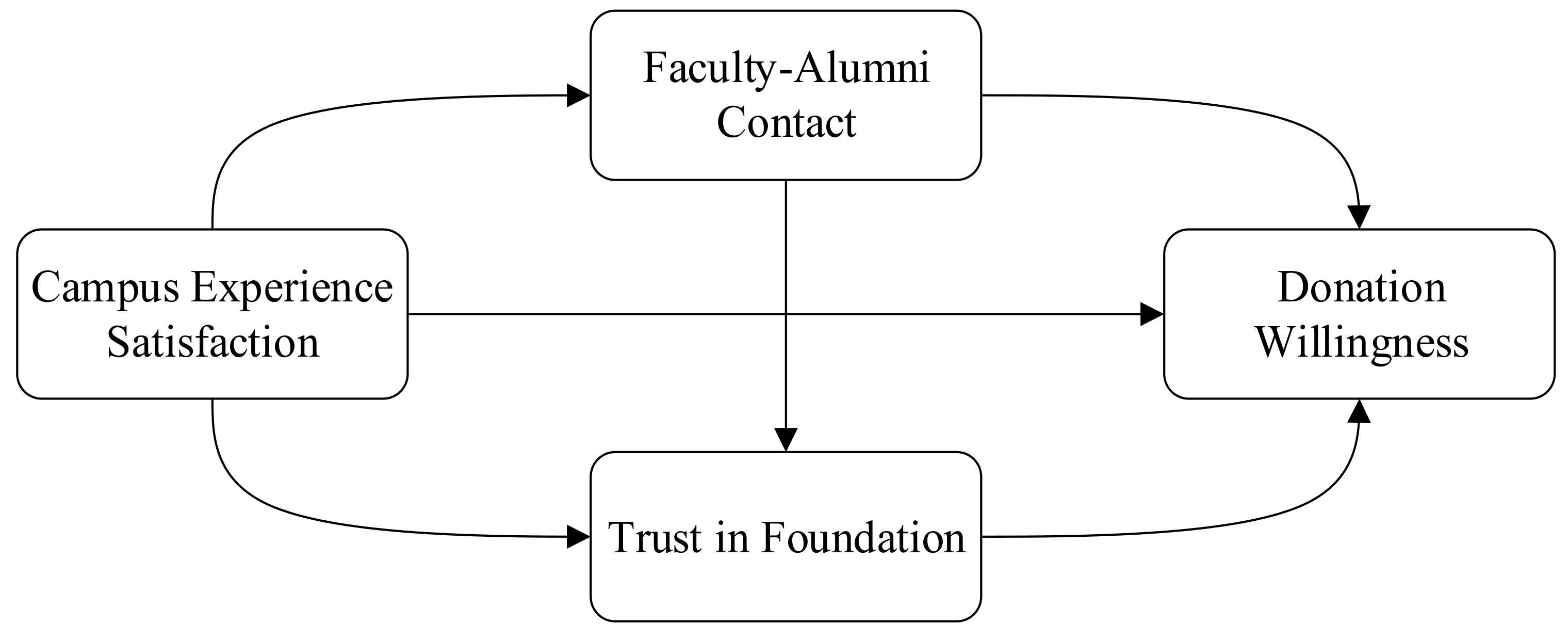

2. Hypothesis Development

2.1. Campus Experience Satisfaction and Donation Willingness

2.2. Faculty-Alumni Contact and Donation Willingness

2.3. Trust in Foundation and Donation Willingness

2.4. The Mediating Role of Faculty-Alumni Contact

2.5. The Mediating Role of Trust in Foundation

2.6. The Sequential Mediating Role of Faculty-Alumni Contact and Trust in Foundation

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedure

3.2. Measurement

4. Data Analysis and Results

4.1. Common Method Bias

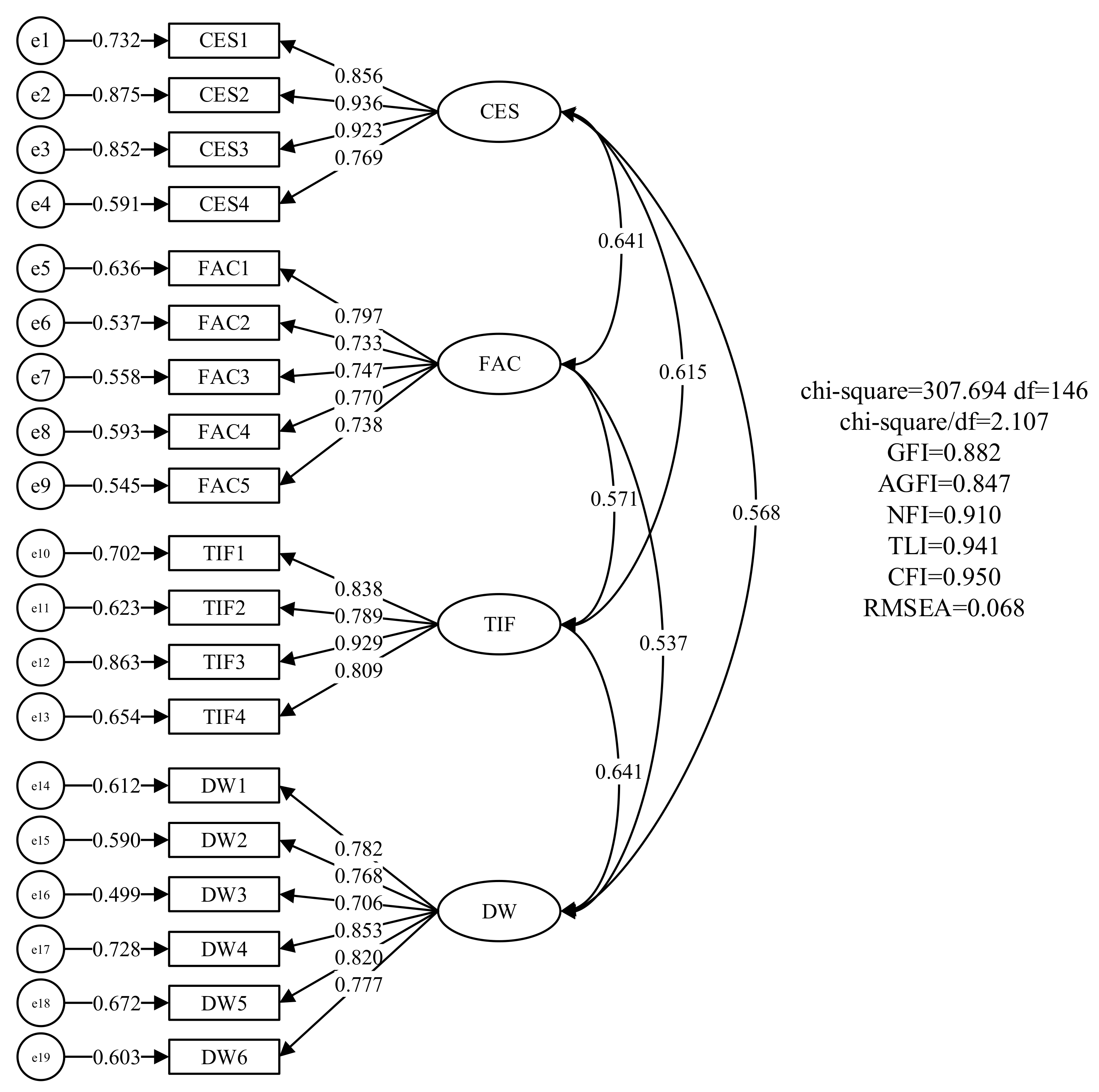

4.2. Measurement Model

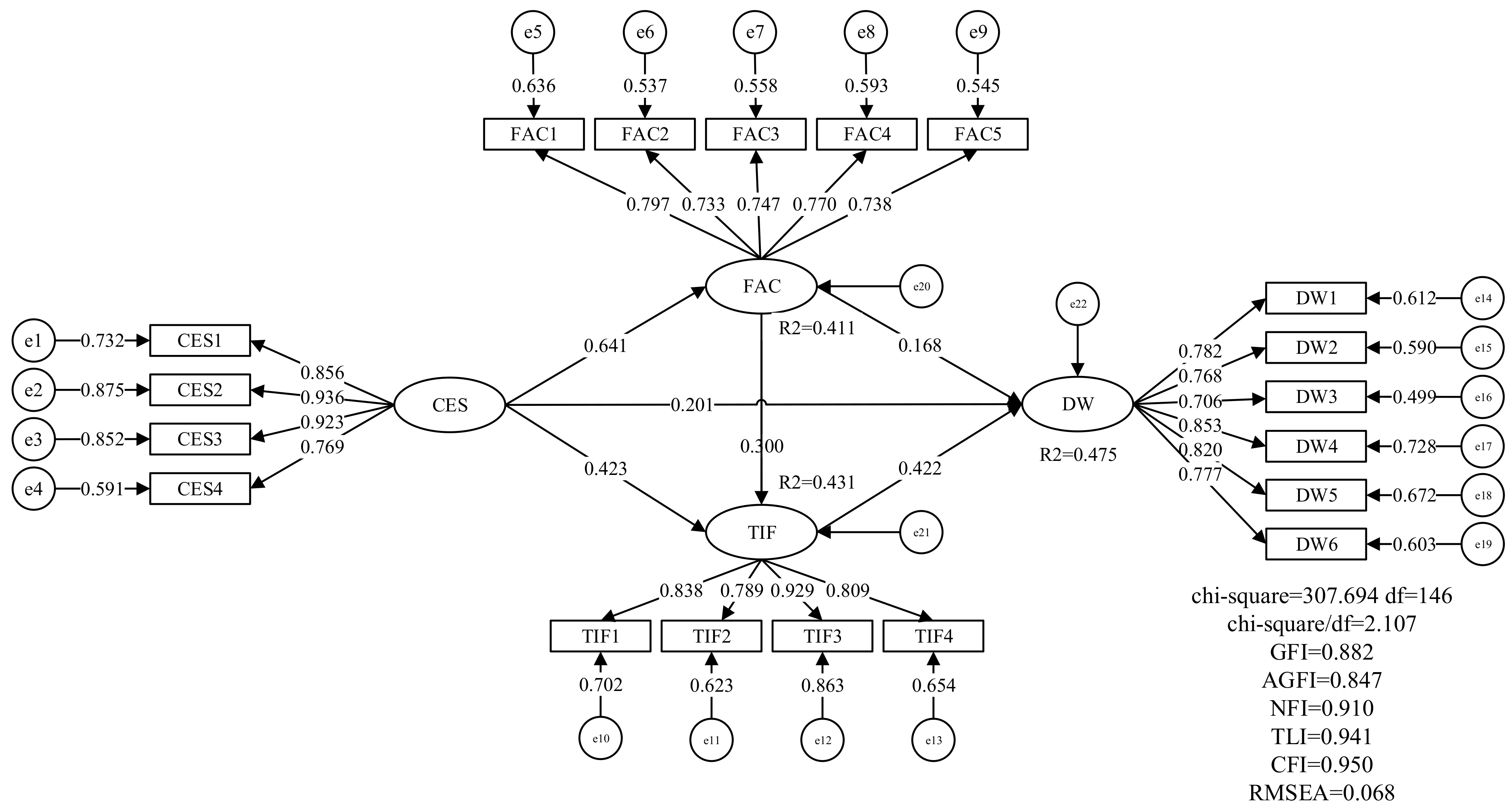

4.3. Structural Model

4.4. Mediation Effect Analysis

5. General Discussion

5.1. Summary and Explanation of Findings

5.2. Theoretical Implications

5.3. Managerial Implications

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stephenson, A.L.; Yerger, D.B. The Role of Satisfaction in Alumni Perceptions and Supportive Behaviors. Serv. Mark. Q. 2015, 36, 299–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council for Aid to Education. 2016/2017 Voluntary Support for Education [EB/OL]. 2018. Available online: Https://Cae.Org/Images/Uploads/Pdf/VSE-2017-Press-Release.Pdf (accessed on 8 March 2018).

- Drezner, N.D. Philanthropic Mirroring: Exploring Identity-Based Fundraising in Higher Education. J. High. Educ. 2018, 89, 261–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohayati, M.; Najdi, Y.; Williamson, J. Philanthropic Fundraising of Higher Education Institutions: A Review of the Malaysian and Australian Perspectives. Sustainability 2016, 8, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, C.-I. Investigating Philanthropy Initiatives in Chinese Higher Education. Volunt. Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Organ. 2016, 27, 2514–2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airuishen Research Institute. 2021Chinese University Alumni Giving Rankings. Available online: Http://www.Chinaxy.Com/2022index/News/News.Jsp?Information_id=1915 (accessed on 13 March 2022).

- Poole, S.M. Developing Relationships with School Customers: The Role of Market Orientation. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2017, 31, 1054–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francioni, B.; Curina, I.; Dennis, C.; Papagiannidis, S.; Alamanos, E.; Bourlakis, M.; Hegner, S.M. Does Trust Play a Role When It Comes to Donations? A Comparison of Italian and US Higher Education Institutions. High. Educ. 2021, 82, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snijders, I.; Wijnia, L.; Rikers, R.M.J.P.; Loyens, S.M.M. Alumni Loyalty Drivers in Higher Education. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2019, 22, 607–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drezner, N.D.; Pizmony-Levy, O. I Belong, Therefore, I Give? The Impact of Sense of Belonging on Graduate Student Alumni Engagement. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2021, 50, 753–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaier, S. Alumni Satisfaction with Their Undergraduate Academic Experience and the Impact on Alumni Giving and Participation. Int. J. Educ. Adv. 2005, 5, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meer, J.; Rosen, H.S. The Impact of Athletic Performance on Alumni Giving: An Analysis of Micro Data. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2008, 28, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monks, J. Patterns of Giving to One’s Alma Mater among Young Graduates from Selective Institutions. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2003, 22, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeimah Saraeh, U.; Abdul Rahman, N.I.; Noordin, N.; Ramlan, S.N.; Ahmad, R.; Sakdan, M.F. The Influence of Students’ Experience on Alumni Giving in Malaysian Public Educational Institution. MATEC Web Conf. 2018, 150, 05030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Carson, B.H. Thirty Years of Stories: The Professor’s Place in Student Memories. Change Mag. High. Learn. 2010, 28, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clotfelter, C.T. Interracial Contact in High School Extracurricular Activities. Urban Rev. 2002, 34, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisby, B.N.; Sidelinger, R.J.; Tatum, N.T. Alumni Recollections of Interactions with Instructors and Current Organizational Identification, Commitment, and Support of the University. Commun. Rep. 2019, 32, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iskhakova, L.; Hoffmann, S.; Hilbert, A. Alumni Loyalty: Systematic Literature Review. J. Nonprofit Public Sect. Mark. 2017, 29, 274–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchheit, S.; Parsons, L.M. An Experimental Investigation of Accounting Information’s Influence on the Individual Giving Process. J. Account. Public Policy 2006, 25, 666–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyndman, N.; Mcconville, D. Transparency in Reporting on Charities’ Efficiency: A Framework for Analysis. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2016, 45, 844–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovits, C.; Shakespeare, C.; Shih, A. The Causes and Consequences of Internal Control Problems in Nonprofit Organizations. Account. Rev. 2010, 86, 325–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heffernan, T.; Wilkins, S.; Butt, M.M. Transnational Higher Education: The Importance of Institutional Reputation, Trust and Student-University Identification in International Partnerships. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2018, 32, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAlexander, J.H.; Koenig, H.F. University Experiences, the Student-College Relationship, and Alumni Support. J. Mark. High. Educ. 2001, 10, 21–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utter, D.B.; Noble, C.H.; Brady, M. Investing in the Future: Transforming Current Students into Generous Alumni. Fund Rais. Manag. 1999, 30, 31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Shank, M.D.; Walker, M.; Hayes, T. Understanding Professional Service Expectations: Do We Know What Our Students Expect in a Quality Education? Serv. Mark. Q. 1996, 13, 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadikoemoro, S. A Comparison of Public and Private University Students Expectations and Perceptions of Service Quality in Jakarta. Ph.D. Thesis, Nova Southeastern University, Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L. SERVQUAL: A Multiple-Item Scale for Measuring Consumer Perceptions of Service Quality. J. Retail. 1988, 64, 12–40. [Google Scholar]

- Marr, K.A.; Mullin, C.H.; Siegfried, J.J. Undergraduate Financial Aid and Subsequent Alumni Giving Behavior. Q. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2005, 45, 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunnava, P.V.; Lauze, M.A. Alumni Giving at a Small Liberal Arts College: Evidence from Consistent and Occasional Donors. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2001, 20, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clotfelter, C.T. Alumni Giving to Elite Private Colleges and Universities. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2003, 22, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frymier, B.; Houser, L. The Teacher-Student Relationship as an Interpersonal Relationship. Commun. Educ. 2000, 49, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korvas, J. The Relationship of Selected Alumni Characteristics and Attitudes to Alumni Financial Support at a Private College. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Missouri-Kansas City, Kansas City, MO, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Mael, F.; Ashforth, B.E. Alumni and Their Alma Mater: A Partial Test of the Reformulated Model of Organizational Identification. J. Organ. Behav. 1992, 13, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.M.; Hunt, S.D. The Commitment-Trust Theory of Relationship Marketing. J. Mark. 1994, 53, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedro, I.H.; Andraz, J.M. Alumni Commitment in Higher Education Institutions: Determinants and Empirical Evidence. J. Nonprofit Public Sect. Mark. 2021, 33, 29–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, L.; Liu, H.K.; Cheng, W. Exploring Factors That Influence Voluntary Disclosure by Chinese Foundations. Volunt. Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Organ. 2016, 27, 2374–2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig-Thurau, T.; Langer, M.F.; Hansen, U. Modeling and Managing Student Loyalty: An Approach Based on the Concept of Relationship Quality. J. Serv. Res. 2001, 3, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helgesen, Ø.; Nesset, E. Images, Satisfaction and Antecedents: Drivers of Student Loyalty? A Case Study of a Norwegian University College. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2007, 10, 38–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, R.D. Measuring Stewardship in Public Relations: A Test Exploring Impact on the Fundraising Relationship. Public Relat. Rev. 2009, 35, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlesinger, W.; Cervera, A.; Pérez-Cabañero, C. Sticking with Your University: The Importance of Satisfaction, Trust, Image, and Shared Values. Stud. High. Educ. 2017, 42, 2178–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Q.; Niu, Y. Governance and Transparency of the Chinese Charity Foundations. Asian Rev. Account. 2019, 27, 307–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.P.; Shen, W. Empirical Methods in Organization and Management Research, 3rd ed.; Peking University Press: Beijing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Trompenaars, F.; Turner, H.C. Riding the Waves of Culture: Understanding Cultural Diversity in Global Business, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Infanger, M.; Bosak, J.; Sczesny, S. Communality Sells: The Impact of Perceivers’ Sexism on the Evaluation of Women’s Portrayals in Advertisements: Sexism and Advertising Effectiveness. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 42, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, X.; Xie, D. Evaluating the Impact of Positive Implicit Followership towards Employees’ Feedback-Seeking: Based on the Social Information Processing Perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.-C.; Hsieh, H.-H.; Tsai, C.-Y.; Cheng, B.-S. Does Value Congruence Lead to Voice? Cooperative Voice and Cooperative Silence under Team and Differentiated Transformational Leadership. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2012, 8, 341–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Wang, F. Three-Dimensional Filial Piety Scale: Development and Validation of Filial Piety Among Chinese Working Adults. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Z.; Wu, N.; Yue, T.; Jie, J.; Hou, G.; Fu, A. How Leader-Member Exchange Affects Creative Performance: An Examination From the Perspective of Self-Determination Theory. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 573793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, M.E.; Quaddus, M.; Shanka, T. Effects of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Quality Cues and Perceived Risk on Visitors’ Satisfaction and Loyalty. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2015, 16, 119–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barclay, D.; Higgins, C.; Thompson, R. The Partial Least Squares (PLS) Approach to Causal Modeling: Personal Computer Adoption and Use as an Illustration. Technol. Stud. 1995, 2, 285–324. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W.; Newsted, P.R. Structural Equation Modeling Analysis with Small Samples Using Partial Least Squares. In Statistical Strategies for Small Sample Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1999; pp. 307–341. [Google Scholar]

- Kahai, S.S.; Cooper, R.B. Exploring the Core Concepts of Media Richness Theory: The Impact of Cue Multiplicity and Feedback Immediacy on Decision Quality. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2003, 20, 263–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, K.M.; Shin, D. Student Satisfaction: An Alternative Approach to Assessing This Important Concept. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 2002, 24, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, S.L. Os Fatores Que Influenciam a Formação da Imagem das Instituições de Ensino Superior: O Caso do Instituto Politécnico de Leiria na Perspetiva dos Professores do Ensino Secundário do Distrito de Leiria [Factors Influencing the Formation of the Image of Higher Education Institutions: The Case of the Polytechnic Institute of Leiria in the Perspective of Secondary School Teachers in the District of Leiria]. Master’s Thesis, Polytechnic Institute of Leiria, Leiria, Portugal, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hartman, D.E.; Schmidt, S.L. Understanding Student/Alumni Satisfaction from a Consumer’s Perspective: The Effects of Institutional Performance and Program Outcomes. Res. High. Educ. 1995, 36, 197–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerts, D.J. Toward an Engagement Model of Institutional Advancement at Public Colleges and Universities. Int. J. Educ. Adv. 2007, 7, 79–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Iacobucci, D. Structural Equations Modeling: Fit Indices, Sample Size, and Advanced Topics. J. Consum. Psychol. 2010, 20, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Organ, D.W. Self-Reports in Organizational Research: Problems and Prospects. J. Manag. 1986, 12, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ylitalo, J. Controlling for Common Method Variance with Partial Least Squares Path Modeling: A Monte Carlo Study; Helsinki University of Technology: Espoo, Finland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, D.L.; Gillaspy, J.A.; Purc-Stephenson, R. Reporting Practices in Confirmatory Factor Analysis: An Overview and Some Recommendations. Psychol. Methods 2009, 14, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doll, W.J.; Xia, W.; Torkzadeh, G.A. A Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the End-User Computing Satisfaction Instrument. MIS Q. 1994, 18, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria Versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y.; Phillips, L.W. Assessing Construct Validity in Organizational Research. Adm. Sci. Q. 1991, 36, 421–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the Evaluation of Structural Equation Models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and Resampling Strategies for Assessing and Comparing Indirect Effects in Multiple Mediator Models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical Mediation Analysis in the New Millennium. Commun. Monogr. 2009, 76, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongbloed, B.; Enders, J.; Salerno, C. Higher Education and Its Communities: Interconnections, Interdependencies and a Research Agenda. High. Educ. 2008, 56, 303–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enders, J.; Fulton, O. Blurring Boundaries and Blistering Institutions: An Introduction. In Higher Education in a Globalising World. International Trends and Mutual Observations—A Festschrift in Honour of Ulrich Teichler; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherland, 2002; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, J. Prestige, Charitable Deductions and Other Determinants of Alumni Giving: Evidence from a Highly Selective Liberal Arts College. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2009, 28, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargeant, A.; Woodliffe, L. Gift Giving: An Interdisciplinary Review. Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Mark. 2007, 12, 275–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographics | Category | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Men | 116 | 48.7% |

| Women | 122 | 51.3% | |

| Age | <23 | 28 | 11.8% |

| 25–35 | 174 | 73.1% | |

| >35 | 36 | 15.1% | |

| Annual income | <100,000 RMB | 75 | 31.5% |

| 100,000–300,000 RMB | 125 | 52.5% | |

| >300,000 RMB | 38 | 16.0% | |

| Qualification | Bachelor’s | 49 | 20.6% |

| Professional master’s | 72 | 30.3% | |

| Academic master’s | 79 | 33.2% | |

| Doctoral | 38 | 15.9% | |

| Occupation | Middle/senior manager | 46 | 19.3% |

| Line manager | 56 | 23.5% | |

| Junior | 126 | 52.9% | |

| Entrepreneur | 10 | 4.2% | |

| Industry type | Mining | 9 | 3.8% |

| Finance/banking | 39 | 16.4% | |

| Manufacturing | 26 | 10.9% | |

| Scientific research institution | 23 | 9.7% | |

| Others | 141 | 59.2% | |

| Work location | Beijing | 164 | 68.9% |

| Shanghai/Guangdong/Shenzhen | 11 | 4.6% | |

| others | 63 | 26.5% | |

| Graduate period | <5 years | 164 | 68.9% |

| 5–10 years | 44 | 18.5% | |

| >10 years | 30 | 12.6% |

| Constructs | Measurement Items | Related Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Campus experience satisfaction | I was satisfied with the teaching service of my alma mater. | Helgesen and Nesset [38] Elliott and Shin [53] Rodrigues [54] |

| I was satisfied with the campus academic activities of my alma mater. | ||

| I was satisfied with the extracurricular recreational activities of my alma mater. | ||

| I was satisfied with the support service of my alma mater. | ||

| Faculty-alumni contact | I kept in frequent contact with my counselor or head teacher after graduation. | Hartman and Schmidt [55] McAlexander and Koenig [23] |

| I kept in frequent contact with my tutor after graduation. | ||

| I kept in frequent contact with one or more subject teachers after graduation. | ||

| I kept in frequent contact with other seniors after graduation. | ||

| I returned to my alma mater frequently after graduation. | ||

| Trust in foundation | The primary goal of the alma mater foundation is to help the university grow rapidly. | Waters [39] Xue and Niu [41] |

| The primary goal of the alma mater foundation is to help poor students. | ||

| The alma mater foundation can distribute donations to the final recipient on time and in full. | ||

| The financial information of the alma mater foundation is open and transparent. | ||

| Donation willingness | I would be more willing to donate if the funds can be used for the development of my subject. | Drezner and Pizmony-Levy [10] Naeimah Saraeh et al. [14] Weerts [56] |

| I would be more willing to donate if it could save poor students from embarrassment. | ||

| I would be more willing to donate if it could help someone close to me. | ||

| I would be more willing to donate if it could fund the research and development of major projects. | ||

| Donating to my alma mater makes me feel a greater sense of belonging. | ||

| I would be more willing to donate when financial conditions permit. |

| Construct | Code | Estimate | S.E. | t-Value | p-Value | Loading | CA | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Campus experience satisfaction | CES1 | 1.000 | 0.856 | 0.925 | 0.928 | 0.763 | |||

| CES2 | 1.275 | 0.063 | 20.315 | *** | 0.936 | ||||

| CES3 | 1.247 | 0.064 | 19.538 | *** | 0.923 | ||||

| CES4 | 0.963 | 0.066 | 14.497 | *** | 0.769 | ||||

| Faculty-alumni contact | FAC1 | 1.000 | 0.797 | 0.870 | 0.871 | 0.574 | |||

| FAC2 | 0.953 | 0.081 | 11.713 | *** | 0.733 | ||||

| FAC3 | 0.958 | 0.081 | 11.852 | *** | 0.747 | ||||

| FAC4 | 0.915 | 0.075 | 12.254 | *** | 0.770 | ||||

| FAC5 | 0.942 | 0.079 | 11.899 | *** | 0.738 | ||||

| Trust in foundation | TIF1 | 1.000 | 0.838 | 0.902 | 0.908 | 0.711 | |||

| TIF2 | 0.926 | 0.065 | 14.298 | *** | 0.789 | ||||

| TIF3 | 1.076 | 0.058 | 18.672 | *** | 0.929 | ||||

| TIF4 | 1.039 | 0.070 | 14.830 | *** | 0.809 | ||||

| Donation willingness | DW1 | 1.000 | 0.782 | 0.905 | 0.906 | 0.617 | |||

| DW2 | 0.959 | 0.077 | 12.519 | *** | 0.768 | ||||

| DW3 | 0.960 | 0.084 | 11.406 | *** | 0.706 | ||||

| DW4 | 1.092 | 0.077 | 14.271 | *** | 0.853 | ||||

| DW5 | 1.077 | 0.079 | 13.579 | *** | 0.820 | ||||

| DW6 | 0.948 | 0.074 | 12.788 | *** | 0.777 |

| Construct | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Campus experience satisfaction | 0.873 | |||

| 2. Faculty-alumni contact | 0.641 *** | 0.758 | ||

| 3. Trust in foundation | 0.615 *** | 0.571 *** | 0.843 | |

| 4. Donation willingness | 0.568 *** | 0.537 *** | 0.641 *** | 0.785 |

| Hypothesis | Path | Std. Estimate | Estimate | S.E. | t-Value | p-Value | Result | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | CES→DW | 0.201 | 0.174 | 0.071 | 2.456 | 0.014 | Support | 0.475 |

| H2 | FAC→DW | 0.168 | 0.124 | 0.060 | 2.045 | 0.041 | Support | |

| H3 | TIF→DW | 0.422 | 0.350 | 0.066 | 5.266 | *** | Support | |

| H4 | CES→FAC | 0.641 | 0.755 | 0.082 | 9.170 | *** | Support | 0.411 |

| H6 | CES→TIF | 0.423 | 0.443 | 0.083 | 5.302 | *** | Support | 0.431 |

| H8 | FAC→TIF | 0.300 | 0.266 | 0.072 | 3.684 | *** | Support |

| Path | Bootstrapping | BC 95% CI | Effect of | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Point Estimate | S.E. | Lower | Upper | |||

| Indirect effect | CES-FAC-DW | 0.108 | 0.059 | 0.001 | 0.238 | 19.01% |

| CES-TIF-DW | 0.178 | 0.055 | 0.087 | 0.306 | 31.34% | |

| CES-FAC-TIF-DW | 0.081 | 0.028 | 0.038 | 0.152 | 14.26% | |

| Total indirect effect | CES on DW | 0.367 | 0.070 | 0.236 | 0.513 | 64.61% |

| Direct effect | CES on DW | 0.201 | 0.093 | 0.027 | 0.394 | 35.39% |

| Total effect | CES on DW | 0.568 | 0.061 | 0.445 | 0.683 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mo, L.; Zhu, Y. How Is Alumni Giving Affected by Satisfactory Campus Experience? Analysis of an Industry-Research-Oriented University in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7570. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14137570

Mo L, Zhu Y. How Is Alumni Giving Affected by Satisfactory Campus Experience? Analysis of an Industry-Research-Oriented University in China. Sustainability. 2022; 14(13):7570. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14137570

Chicago/Turabian StyleMo, Leiyu, and Yuting Zhu. 2022. "How Is Alumni Giving Affected by Satisfactory Campus Experience? Analysis of an Industry-Research-Oriented University in China" Sustainability 14, no. 13: 7570. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14137570

APA StyleMo, L., & Zhu, Y. (2022). How Is Alumni Giving Affected by Satisfactory Campus Experience? Analysis of an Industry-Research-Oriented University in China. Sustainability, 14(13), 7570. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14137570