Abstract

Biodiversity at the species and ecosystem level is an important basis for tourism, especially for tourism economies in landscapes optimal for the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity, which are addressed under the Convention on Biological Diversity. In the last two decades, the Podocnemis Unifilis turtle has presented problems represented in a decrease of individuals in their populations in the Ecuadorian Amazon. The objective of the study was to describe the characteristics and current situation of the charapa turtle (Podocnemis Unifilis), to analyze the perception of the community of the Indillama River towards this species and finally to establish a proposal for its conservation with a socio-economic contribution from the community tourism segment. The methodology used consisted of a bibliographic review, semi-structured interviews and expert judgment. The main results indicate that the charapa turtle has had population problems in the last 30 years due to various anthropogenic pressures. The inhabitants of the Río Indillama community perceive this species mainly as a source of economic income (sale of individuals and their eggs) and food by consuming their eggs and adult individuals. Finally, we present a proposal for conservation through tourism that provides experiential activities for the collection of P. unifilis eggs, nesting and release (sponsorship) of individuals, providing economic benefits to local communities. This will contribute to its conservation and local socioeconomic development.

1. Introduction

Biological diversity is the result of billions of years of evolution, in which it has been affected by natural processes and human activity. Biodiversity has a truly incalculable value, not only because of its immense variety but also because of the functions it fulfills, functions that are irreplaceable [1]. Over the last 50 years, biodiversity has been decreasing at an alarming rate, mainly due to human activities. This loss represents a threat to human beings and, paradoxically, is largely a consequence of their own activity, such as changes in land use, pollution and climate change [2,3].

Today, there is an enormous and growing interest in the natural world, and natural protected areas provide the opportunity to interact with nature [4]. Protected areas are one of the main environmental management tools for safeguarding natural ecosystems and the animal and plant species that inhabit them [5,6]. Natural protected areas are essential for biodiversity conservation. They are intended to maintain functioning natural ecosystems, act as refuges for species and maintain essential ecological processes [7,8].

Tourism is one of the main economic sectors worldwide, being the object of study in various geographic destinations. This economic activity operates as a source of opportunities for the socioeconomic and cultural modernization of a geographical area, and heritage is a factor of social cohesion due to the important sensitivities it affects [9,10]. Consequently, models that revolve around the sustainable development of a destination’s tourism are more frequent. In this sense, cultural, natural and heritage resources are part of a network of great value and wealth, which should be promoted and marketed in a sustainable manner, with the aim of improving the socioeconomic development of local populations in the destinations and the conservation of resources [11].

The main motivation of nature tourism is to carry out recreational and recreational activities in the natural environment without altering its balance. It promotes the conservation of nature and existing ecosystems, carrying out re-creative activities of appreciation and knowledge through interaction [12,13]. Biodiversity at the species and ecosystem level constitutes an important basis for tourism, especially for rural and indigenous communities seeking additional economic income [14]. Responsibly managed tourism activities contribute significantly to biodiversity conservation. They can even increase the populations of certain key species, in addition to raising awareness of the value of biodiversity and its ecosystem services [15,16,17]. In Ecuador, biodiversity is a strategic ally for promoting sustainable tourism. Protecting this type of tourism is essential for promoting social inclusion, employment and poverty reduction [15,18]. Thus, this type of tourism is becoming more popular in the Amazon region, with greater numbers of tourists visiting national parks, protected areas, unique ecosystems and their communities. The need to integrate biodiversity with tourism and the socioeconomic development of its peoples is of increasing interest among researchers and managers in protected areas in search of sustainable development.

In Latin America and the Caribbean, a significant number of rural communities have integrated tourism activities into their social, productive and economic dynamics as an alternative to fight poverty, incorporating the inhabitants, who are sometimes indigenous and mestizo groups, generating a new form of tourism that has been called Rural Community Tourism [19,20,21,22]. This type of tourism has been implemented in rural areas where the local inhabitants, organized collectively, play a participatory role in its progress, management and monitoring, ensuring respect for the natural environment, socio-cultural [23] and ancestral values of their community [24], allowing a pleasant, favorable and reciprocal enjoyment of experiences between local people and tourists (visitors). This interrelation tourist–rural community should be characterized by justice in the equitable distribution of the benefits generated by the execution [22,25,26]. In short, this segment of tourism in the last two decades will increasingly generate greater economic returns for local populations, presenting itself as an easy and quick strategy for development and the fight against poverty, capable of generating benefits with very little investment, since its main attraction is biodiversity, its landscape and culture [27,28].

In the Ecuadorian Amazon as in other parts of the world, the development of at least three practical applications of the relationship between conservation and local populations can be seen as a type of conservation model with local people [16]. They can therefore only be distinguished analytically since in practice they are combined in different ways. The first refers to preservation “for” the well-being of the people. The second model deals with conservation “with” the people, that is, with the participation of indigenous peoples and people who are considered subjects of certain conservation actions, but who are not key decision-makers. The third model deals with conservation “by” people. It considers local people as a determining factor for conservation. It assumes that conservation sustainability in the long term is only possible if the organized local population takes charge and establishes its own self-regulation mechanisms [29,30,31].

There is no doubt about the importance of the participation of indigenous or local communities in biodiversity conservation processes [32]. They play a key role in providing knowledge and contributing to work in the territory at different stages of biological conservation [33]. Since 1990, the P. unifilis turtle has presented problems represented by a decrease in the number of individuals in its population in the Ecuadorian Amazon. In view of this situation, it has been considered necessary to design and apply a conservation strategy to increase the population of P. unifilis turtles, with the collaboration of an indigenous community in Yasuní National Park and to be considered as a nature tourism product [34,35].

In this sense, the objective of this article was initially focused on describing the current situation of the Charapa turtle (P. unifilis), with respect to its conservation status. Next, to learn about the historical and current use of the species in the community of Río Indi-llama; and, finally, to establish a proposal that would allow its sustainable use for tourism purposes and contribute to its conservation. Three methodological techniques were used for the development of this research: bibliographic review, field interview and expert judgment. The results demonstrate that it is possible to sustainably exploit a species in a vulnerable state, allowing one to dynamize the local economy and also contribute to its conservation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The Río Indillama community is located in the Alejandro Labaka parish, Francisco de Orellana canton, Orellana Province, 80 km downstream from the city of El Coca, on the banks of the Napo River (Figure 1). It is bordered to the north by the Napo River, to the south by the Tiputini River and Yasuní National Park, to the east by the Nueva Providencia community and to the west by the Pompeya community [36]. The Río Indillama community has 14,000 hectares, including flooded and hilly forests; all of its inhabitants are Kichwa [27]. The projected population in 2019 was 250 inhabitants. There are two alternatives to reach the community: by river, from Puerto Francisco de Orellana in canoes; the second alternative to reach the community is by land from Puerto Francisco de Orellana to Puerto Itaya in interprovincial buses [34,36].

Figure 1.

Location of the study area in Ecuador.

This area is characterized by its great biodiversity, with a large number of tree species with canopies of 35–40 m in height, species such as ceibo, guarumo, balsa, higuerón, laurel and a variety of herbaceous plants that grow along the banks of the Napo River [36]. More than 38 mammal, 81 bird, 8 reptile and 4 fish species have been recorded. The community is dedicated to agricultural activities, planting products for family sustenance and very few for commercialization. The main crops are: yucca, plantain, lemon, sugar cane, guaba, wild grapes, rice, hard chonta, among others [37].

2.2. Methods

For a better understanding of the methodological process, this section has been divided into three sections. The first section focused on a search for information from scientific publications on the description and current status of the species P. unifilis in the Amazon basin. The second section analyzed the social perception of the inhabitants of the Río Indillama community in Yasuní National Park towards the charapas turtles. Finally, a proposal for community-based conservation tourism was proposed to improve the community’s economy and guarantee the protection of P. unifilis in the Río Indillama community in Yasuní National Park.

To respond to the first objective regarding the conservation status of the charapa turtle (P. unifilis), it was necessary to conduct a literature review based on scientific publications corresponding to the last five years (2017–2021). This information search was carried out in high-impact databases such as Scopus and Web of Science; and, regional databases such as Scielo and Redalyc. In the bibliographic review process, search parameters were applied, resulting in 43 documents, 40 high impact (23 Web of Science and 17 in Scopus) and three regional (0 in Scielo and 3 in Redalyc). Next, in order to filter the results, the titles and summaries were read and only 19 documents were considered for the final analysis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Search parameters for the literature review.

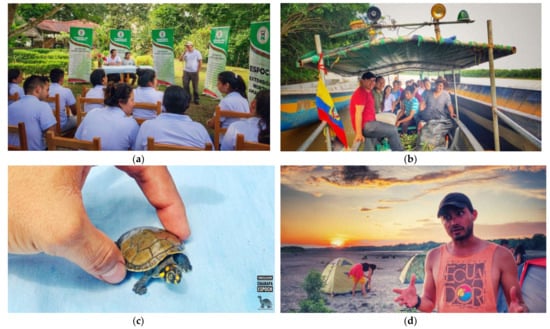

With respect to the second objective and to learn about perceptions, field visits were made to the Río Indillama community, where a meeting was held with the community president and the rest of the inhabitants. During the visits to the study area (Figure 2b), semi-structured interviews (Table 2) were conducted, that is, open-ended questions directed to focal groups in the community (Figure 2a). A total of 12 people were interviewed, including community leaders and the tourism association, that is, people who have knowledge about the charapas turtles (Figure 2c). Each interview was conducted in the form of a conversation so that people could feel confident (Figure 2d). The main objective of the visit was to know the perception of the inhabitants towards the charapa turtle. The following are the questions that were asked to obtain the results of this objective.

Figure 2.

Entrance to the Río Indillama Community-Yasuní National Park. (a) Socialization of the project and interview with community representatives. (b) Navigation on the Napo River, entrance to the Indillama River Community. (c) Analysis and testing with eggs and hatchlings in the Community. (d) Socialization and indications by the project director in Yasuní National Park.

Table 2.

Questions to know the perception of the inhabitants of the community towards the turtle.

Finally, in the third section, a proposal for community-based tourism involving the conservation of the P. unifilis species was established. For this, the method called expert judgment was used, which consisted of a compilation of opinions provided by professional experts on a given topic to verify the credibility of the research. Similarly, a discussion and a round table were organized with the participation of researchers who contributed different perspectives to the subject of the proposal (Table 3).

Table 3.

Experts and social actors involved in the tourism proposal.

The results obtained in the previous steps of this research were given to this group of professionals so that they could learn about the current status of the charapa turtle at the national and local levels, as well as the perception of the inhabitants of the study area towards this species.

3. Results and Discussions

Once the methodological process to know the conservation status of the charapa turtle, the perception of the inhabitants of the sector and carrying out the community tourism proposal has been explained, the results are presented in an orderly manner responding to the objectives of this study. Next, the results are presented in an orderly manner in response to the objectives of this study. The first section describes the main characteristics and current status of the species P. unifilis, based on a bibliographic review. The second section analyzes the perception of the inhabitants of the Río Indillama community of the charapa turtles. Finally, the proposal elaborated with the help of different experts on the subject is presented.

3.1. Descripción y Estado Actual de la Podocnemis Unifilis

The species P. unifilis is one of the largest freshwater turtles, also known as charapa or side-necked turtles because they cannot completely insert their head into the shell, but have to bend their neck to one side to attach, leaving a part open [23]. The habitat of the charapa turtle are areas that correspond to water courses, arms, lagoons or lakes interconnected to abundant rivers. Their diet mainly corresponds to various aquatic plants, herbs, fruits, seeds, flowers, roots and stems found on the coast and sometimes also small animals such as crustaceans, insects, mollusks, fish, eggs and even carrion. In the dry seasons, individuals come out and congregate in the main rivers or rivers near the beaches for mating and spawning. This species lays its eggs on the banks of dry rivers to prevent the nests from being washed away [46]. The charapa spends most of its time underwater and prefers the main channels of large rivers. It spawns in the summer season and nests solitarily in ravines and vegetated areas [54].

The species differs from other Podocnemis species by the combination of the following characteristics: (i) unicarenate carapace with strongly reversed anterior edge expanding towards the caudal region; (ii) carapace with a slightly raised keel on vertebral scutes V2 and V3; (iii) convex and oval carapace; (iv) yellow cephalic spots: one rounded on each lateral margin of the interparietal scale, one on the end of the rostrum, one on the tympanum and two on the maxillary ranophotheca; (v) one barbule on the chin (less frequently two); (vi) three axillary pores on the bridge and one inguinal pore; (vii) legs completely webbed; (viii) plastron smaller than the carapace, with the anterior region longer, wider and rounder than the posterior region; (ix) two large frontal parietal scales, one interparietal groove and one large tympanic membrane; (x) plastral formula [55,56].

The breeding cycle of the charapa is annual, which is closely related to the periods of rain and drought in the Amazon area, that is, with the rise and fall of river levels. In the spawning and incubation process, this species prefers high and extensive sandy beaches, so these processes occur when river levels are at their lowest, and their sands are completely exposed and dry, usually after 10 to 15 days of sunshine. The charapa spawning is a collective activity, the number of individuals that congregate will depend on the surface area of the beaches available, developing mainly at night. Hatching generally coincides with the beginning of the rainy season and the increase in river flow. In the study area of the Napo River in the Indillama River Community sector, the main nesting season takes place between September and non-November, with isolated nesting occurring in August and December.

The charapa turtle is classified as Vulnerable (VU) in the Red List of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) [19]. However, each country has its own rating, and they are available in red books to evaluate the status of each species, but only within its territory. In this case, the national risk category should refer to the 2005 Red List of Reptiles of Ecuador, where the charapa is categorized as Critically Endangered. This specimen is very important within its ecosystem because of the crucial ecological role they play as seed dispersers, cleaners of the aquatic system and as a food source for other species of aquatic fauna [35,57]. In Ecuador, charapas are threatened by the increasing illegal co-commercialization and exploitation of their meat and eggs for human consumption, as well as the capture and sale of juveniles and adults as domestic pets [58].

The main threat to the charapa turtle is indiscriminate hunting, an activity that has been carried out since pre-Hispanic times due to its great importance as a food resource because of its high nutritional value. This has caused turtle populations to decrease [59]. Another threat is the exploitation of eggs and hatchlings for food and aphrodisiac purposes, which has prevented them from maintaining a regular reproductive rate [60]. It has been observed that in some communities a large number of hatchlings are captured and used as pets for children in the communities [46,54], or are sold to settlers for the same purpose [24].

3.2. Historical and Current Use of the Charapa Turtle (Podocnemis unifilis)

The first words with which the inhabitants of the Río Indillama community relate the term turtle are: “food”, “money”, “shell”, “pity” and “curiosity”. For the indigenous thought, in the discursiveness of the myth, the beings of nature are perceived from the status of humanity, but not of species; it is the animal and the vegetables who are framed in many cases deontologically in relation to humans [61]. Thanks to the interviews, it was possible to know the perception of the inhabitants of the commune towards the charapas turtles. The main activities of the community’s inhabitants are fishing and agriculture.

The people interviewed reviled that historically the species was exploited first by the indigenous people and later by settlers who came to their territory from different places. The historical interest in the species lies in taking advantage of its meat and collecting its eggs during the spawning season. Year after year, a large number of indigenous people and settlers travel the banks of the Napo River from Puerto Pompeya, near the Limoncocha Biological Reserve, to the northern border of Yasuní National Park in the Indillama River Community and Puerto Providencia. Each turtle egg can be traded for between 0.15 to 0.25 cents and an adult turtle can easily sell for between 15 to 25 dollars. As for where they are sold, some people commented that they are obtained from neighbors, veterinarians and the market.

From a nutritional standpoint, the charapa turtle has historically provided a large amount of protein for the indigenous people living along the Napo River during the dry season, which coincides with the laying season. This resource has been so important that groups from the interior of the jungle move during these seasons to take advantage of the abundance of individuals and their eggs. Each season between September and November, up to 200 turtles and approximately 1200 eggs are captured in the Indillama River-Yasuní National Park sector. To capture the eggs, the indigenous people or settlers at dawn are guided by the footprints left by the turtles in the sand after the process of going to the beach to lay their eggs and returning to the river. Different techniques have been used to hunt the species. Among the techniques used to capture turtles, they mainly mention spear fishing, hook and line fishing, traps and diving. Community residents do not have specific tools for turtle fishing. A common method is to look for feces floating in the water; if they perceive that they are complete they indicate that they are less than 50 m away, so they wait for them to come up for air before capturing them.

Once the turtles are captured, the entire body is usually consumed. The main dishes prepared are: turtle stew and stewed with masa, yucca and plantain; other dishes mentioned were in marinade, broth and soup. They mentioned that all turtles can be used as food since their meat has a sweet flavor, but the texture is very soft, so they recognize the charapa turtle as the most in-demand because its meat is considered the tastiest of all because it has a harder texture that gives it a better flavor, and it is also easy to catch. It is very common to save turtle meat for special occasions, such as visits from authorities or local events.

The oil from the charapa turtle is preserved for medicinal and protective purposes. One of the main uses is to apply this oil twice a day on the body and it serves as a repellent. Another common use is to consume the oil because it cleanses the stomach in case of discomfort. A minimum number of interviewees mentioned that they generally use the neonates as a pet for children. In the past, the charapa turtle shell was used to shuck corn and as an accessory in the construction of canoes, but this practice is no longer used because there are now other tools for these activities.

Those interviewed agreed that the charapa turtles are used for food and economic purposes. During the nesting season, the inhabitants of the Río Indillama community capture adult individuals and their eggs; a percentage is consumed or preserved for food, while another percentage earns income from the sale of adult individuals and eggs. During the hatching season, the hatchlings are captured and sold as pets to colonists. When interviewees were asked if it was necessary to implement projects to preserve the charapa species, they argued that it would be very feasible, because it is evident that its population is decreasing, and as a result, there are fewer resources (individuals, eggs and hatchlings). As strategies, they considered environmental education in their populations and trying to link the species to conservation processes and tourism to be opportune.

3.3. Community-Based Conservation Tourism Proposal

At present, the Río Indillama Community has been developing a community-based tourism activity that involves approximately 30 people in its management and the entire community as active decision-makers. This type of tourism is where small rural communities share their homes with tourists and allow them to learn about their customs, daily life and ancestral knowledge. It is important to note that the tourism activity manager affirms that since the emergence of community-based tourism in the Indillama River Community, it has never been consolidated. From the point of view of the tourism managers, it is indicated that one of the problems for not consolidating has been incorrect management. On the other hand, researchers state that another serious problem that limits the consolidation of tourism activities is the lack of tourism activities and the consolidation of a quality tourism product.

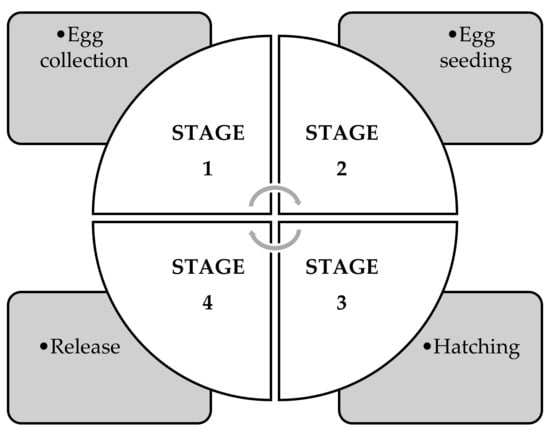

In this context, after analyzing the reality of tourism in the Río Indillama community and learning about the potential of the charapa turtle (P. unifilis) as a tourism resource based on its different historical and current uses, a proposal was developed to implement tourism activities that involve the charapa turtle and contribute to its conservation, considering that one of its biggest problems is its low birth rate and high mortality rate in hatchlings. The proposal is composed of four phases (Figure 3), from the time the charapas lay eggs on sandy beaches, their collection, seeding in artificial sand banks and final release in their natural habitat. These activities will be carried out with the collaboration of tourists visiting the Río Indillama Community.

Figure 3.

Proposal design.

Stage 1. Egg collection.

Tourists are directly involved in activities to collect charapa turtle eggs in order to ensure their protection. They are given an induction class on the subject of the project. This process of collecting the charapa turtle has an environmental education component, through which the communities and visitors learn about the risks of this species due to indiscriminate hunting so that they become the main protectors and harmonize life between the people who live along the riverbanks and wildlife.

Stage 2. Egg seeding.

Artificial incubators prevent the loss of nests due to flooding and predators. From November to February in the Amazon, the eggs hatch in artificial sand at a depth of 7 to 18 cm for 45 to 60 days; with a temperature of 25.3 to 32.7 degrees Celsius and 20 eggs are laid per nest. The depth varies according to the number of eggs in the nest; the greater the volume of the nest, the greater the number of eggs it contains. To ensure the greatest possible number of hatchlings, the nests should be monitored daily to avoid access to species that may affect the incubation process.

The participation of visitors is reflected in the observations and it is possible that they are directly involved in the seeding process as long as they have been previously trained to avoid moving the position of the eggs, each nest is marked with codes that indicate the date and name of the beach where they were collected.

Stage 3. Hatching.

Once the turtle eggs have hatched, the number of live hatchlings is counted and they will be transferred to a tub with wet sand, where they will remain for 2 or 3 days in a shaded place until the navel heals and the blood loss from the egg hatching is minimal. Then, they will be measured, weighed and monitored until they are ready to be transferred to the artificial pool. The hatching season is from October to March, after which visitors can be part of the hatchling release process on the beaches of the Indillama River.

Stage 4. Release.

The turtles will be kept in artificial pools with food (malanga leaves, sweet potato, nettle and Chinese potatoes). After one year, which is the recommended time, they are encrypted and placed in a container for careful handling on the wet sand on the beaches from which the eggs were collected. Prior to the turtle release, a sponsorship event will take place, in which tourists will name the turtle and follow the species on its journey until it reaches its aquatic habitat. The cost of releasing the turtles is a minimum of USD 5 per person. During the sponsorship event, traditional dances and craft shows will be used to promote indigenous culture, generating economic income for the community and imparting ancestral and cultural knowledge. At the end of the stages, a certificate will be issued certifying the tourist’s participation in the process, which is part of the objective of conserving biodiversity through the preservation of a species, thus achieving a unique experience.

4. Conclusions

According to Ecuador’s 2005 Red List of Reptiles, the charapa is listed as Critically Endangered. This specimen is important in its ecosystem due to the important ecological role it plays as a seed disperser, cleaner of aquatic systems and food source for other aquatic animals. In Ecuador, charapas are threatened by the increasing commercialization and illegal exploitation of their meat and eggs for human consumption, as well as the capture and sale of juveniles and adults. This turtle is an animal that has been used as a food source since pre-Hispanic times due to its abundance in the area, although turtle populations are now in decline and there are legal restrictions, which is why its consumption continues to be deeply rooted in certain places and cultures in Ecuador and South America.

The area of the Rio Indillama community on the northern boundary of Yasuní National Park has been recognized over time by local communities as a strategic point for the capture of laying females and the extraction of eggs, which are collected during the summer, ignoring the prohibitions on hunting and egg collection that exist for these species by the environmental authority, the Ministry of Environment, Water and Ecological Transition of Ecuador. Thus, this extractive activity is evidence of the problem of harvesting these species as a resource, and there is a need to work as a team with local communities by formulating conservation strategies that contribute to the sustainable management of both turtle species and the resources offered by the protected area. Some of the strategies mentioned to protect the turtles were to create surveillance and monitoring groups, protect the places where they live, take care of the environment, the river and the lagoon, avoid hunting for commercial purposes, keep their capture prohibited, inform people of their importance in the environment, have conservation programs, check boats and provide continuity to species conservation projects.

Finally, this project proposal will contribute to the conservation of the species by increasing its birth rate and recovering its populations. As well as involving visitors in their community tourism activity in the activities of collecting, sowing, hatching and releasing eggs and hatchlings. This process will be called “sponsorship of a charapa turtle”. One of the main limitations in developing the study was the lack of interest of the locals in participating in the elaboration of the proposal, due to the low income that this activity generates in the Indillama River Community. New researchers are encouraged to generate new tourism activities to link the present and create more attractive tourism products. Likewise, we believe it is vitally important to generate new linkage projects where work is focused on socializing the proposal with the members of the Río Indillama community about its importance in the conservation of the charapa turtle (P. unifilis), tourism and its sustainability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, C.M.-R. and D.M.-S.; formal analysis, C.M.-R., R.L.-V., D.M.-S., C.B.M., A.S.-H., M.S.-C. and A.C.-G.; investigation, C.M.-R., R.L.-V., D.M.-S., C.B.M., A.S.-H., M.S.-C. and A.C.-G.; writing—original draft preparation, C.M.-R. and D.M.-S.; writing—review and editing, C.M.-R. and D.M.-S.; supervision, C.M.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was financed by the Escuela Superior Politécnica de Chimborazo, within the project “Dinamización de la economía mediante la implementación de un producto turístico de conservación sostenible, para mejorar la calidad de vida y protección del ambiente en la comunidad Río Indillama, Parque Nacional Yasuni”.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting this study will be available upon request from the first and second authors of the study.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Escuela Superior Politécnica de Chimborazo (ESPOCH) for providing the facilities for the execution of the project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Colli, G.R.; Vieira, C.R.; Dianese, J.C. Biodiversity and conservation of the Cerrado: Recent advances and old challenges. Biodivers. Conserv. 2020, 29, 1465–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-Silveira, M.-J.; Barros, S.G. El estudio de la biodiversidad. Alambique Didáctica Las Cienc. Exp. 2015, 79, 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Púrez Miranda, C. Tucumán y Los Recursos Naturales. Biodiversidad, Los Recursos Silvestres, Los Ambientes Naturales y Las Áreas Protegidas. Caracterización, Evolución, Situación Actual y Marco Legislativo; EPDA, PROSAP; Gobierno de la Provincia de Tucumán: San Miguel de Tucumán, Argentina, 2006; ISBN 9879471210. Available online: https://agris.fao.org/agris-search/search.do?recordID=AR2006000193 (accessed on 18 April 2022).

- Encabo, M.; Mastrocola, Y.I.; Vázquez, V. La conservacíón de la biodiversidad y los servicios turísticos. Augmdomus 2013, 5, 33–46. [Google Scholar]

- Halffter, G. Conservación de la biodiversidad y áreas protegidas en los países tropicales. Ciencias 1994, 36, 4–13. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, G.J.; Manzano-García, J. Estilos de percepción de la biodiversidad y su conservación en actores sociales de áreas protegidas de Córdoba. Rev. Mus. Antropol. 2016, 9, 135–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halffter, G.; Ezcurra, E. La diversidad biológica de Iberoamérica; CYTED-D, Programa Iberoamericano de Ciencia y Tecnologia para el Desarollo; Instituto de Ecología, A.C.: Xalapa, Mexico, 1992; Volume 1, ISBN 9687213310. [Google Scholar]

- Monjeau, J.A. Conservación de la biodiversidad, áreas protegidas y gente: Escalas diferentes, problemas diferentes. In Unidades de Conservação: Atualidades e Tendências; Fundação O Boticário de Proteção à Natureza: Curitiba, Brazil, 2007; pp. 77–91. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Adrian-Monjeau/publication/298792009_Conservacion_de_la_biodiversidad_parques_gente_escalas_diferentes_problemas_diferentes/links/56ec0f3a08aee4707a384e99/Conservacion-de-la-biodiversidad-parques-gente-escalas-diferentes-problemas-diferentes.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2022).

- Unwto. Unwto World Tourism Barometer and Statistical Annex, January 2021. UNWTO World Tour. Barom. 2021, 19, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croes, R. The role of tourism in poverty reduction: An empirical assessment. Tour. Econ. 2014, 20, 207–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestanza-Ramón, C.; Jiménez-Caballero, J.L. Nature Tourism on the Colombian—Ecuadorian Amazonian Border: History, Current Situation, and Challenges. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintana, V.M. El turismo de naturaleza: Un producto turístico sostenible. Arbor 2017, 193, a396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra, J.G. La evolución del turismo rural en España y las nuevas oportunidades del turismo de naturaleza. Estud. Turísticos 2006, 169, 85–102. [Google Scholar]

- Jaramillo-Moreno, B.C.; Sánchez-Cueva, I.P.; Tinizaray-Tituana, D.G.; Narváez, J.C.; Cabanilla-Vásconez, E.A.; Muñoz Torrecillas, M.J.; Cruz Rambaud, S. Diagnosis of Administrative and Financial Processes in Community-Based Tourism Enterprises in Ecuador. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Corral, V.H.; Sucoshañay, D.; Álvarez, L.; Castro, P. La actividad ecoturística y su incidencia en la conservación ambiental del Jardín Botánico Las Orquídeas del sector Los Ángeles de Puyo, Pastaza, Ecuador. Rev. Interam. Ambient. y Tur. 2017, 13, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Barrera, C.; Bahamondes, R. Turismo Sostenible: Importancia en el cuidado del medio ambiente. RIAT Rev. Interam. Medioambiente y Tur. 2012, 8, 50–56. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, A.M. Editorial: Land Issues and Their Impact on Tourism Development. Land 2022, 11, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavilanes Montoya, A.V.; Esparza Parra, J.F.; Chávez Velásquez, C.R.; Tito Guanuche, P.E.; Parra Vintimilla, G.M.; Mestanza-Ramón, C.; Vizuete, D.D.C. A Nature Tourism Route through GIS to Improve the Visibility of the Natural Resources of the Altar Volcano, Sangay National Park, Ecuador. Land 2021, 10, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosquera-Laverde, W.E.; Vásquez-Bernal, O.A.; Gomez, E.C.P. Eco-touristic foresight in the Colombian post-conflict for the sustainability of the tourist service with emphasis on ecological marketing. Buenaventura case. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, Pilsen, Czech Republic, 23–26 July 2019; pp. 2428–2436. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo-Vizuete, D.; Gavilanes-Montoya, A.; Chávez-Velásquez, C.; Benalcázar-Vergara, P.; Mestanza-Ramón, C. Design of Nature Tourism Route in Chimborazo Wildlife Reserve, Ecuador. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andries, D.M.; Arnaiz-Schmitz, C.; Díaz-Rodríguez, P.; Herrero-Jáuregui, C.; Schmitz, M.F. Sustainable Tourism and Natural Protected Areas: Exploring Local Population Perceptions in a Post-Conflict Scenario. Land 2021, 10, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, C.; Qin, J.X.; Yin, L. Study on the rural ecotourism resource evaluation system. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2020, 20, 101131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, F.P.; Canestrelli, D.; Boitani, L. Conserving the terecay (Podocnemis unifilis, Testudines: Pelomedusidae) through a community-based sustainable harvest of its eggs. Biol. Conserv. 2005, 126, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagundes, C.K.; Fath, F.; Côrtes, L.G.; Uhlig, V.; Andrade, P.C.M.; Vogt, R.C.; Pezzuti, J.C.B.; De Marco Júnior, P. A large scale analysis of threats to the nesting sites of Podocnemis species and the effectiveness of the coverage of these areas by the Brazilian Action Plan for Amazon Turtle Conservation. J. Nat. Conserv. 2021, 61, 125997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fun, F.S.; Chiun, L.M.; Songan, P.; Nair, V. The Impact of Local Communities’ Involvement and Relationship Quality on Sustainable Rural Tourism in Rural Area, Sarawak. The Moderating Impact of Self-efficacy. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 144, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielinski, S.; Jeong, Y.; Kim, S.-i.; Milanés, C.B. Why Community-Based Tourism and Rural Tourism in Developing and Developed Nations are Treated Differently? A Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado-Erazo, C.P.; del Río-Rama, M.D.; Noboa-Viñan, P.; Álvarez-García, J. Community-Based Tourism in Ecuador: Community Ventures of the Provincial and Cantonal Networks. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucari, N.; Wankowicz, E.; Esposito De Falco, S. Rural tourism and Albergo Diffuso: A case study for sustainable land-use planning. Land Use Policy 2019, 82, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Martín, J.M.; Sarmiento-Ramírez, J.M.; Diéguez-Uribeondo, J. Beyond Sea Turtles: Fusarium keratoplasticum in Eggshells of Podocnemis unifilis, a Threatened Amazonian Freshwater Turtle. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz Barriga, A. Percepciones de la gestión del turismo en dos reservas de biosfera ecuatorianas: Galápagos y Sumaco. Investig. Geográficas Boletín del Inst. Geogr. 2017, 2017, 110–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floris, M.; Gazale, V.; Isola, F.; Leccis, F.; Pinna, S.; Pira, C. The Contribution of Ecosystem Services in Developing Effective and Sustainable Management Practices in Marine Protected Areas. The Case Study of “Isola dell’Asinara”. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, J.R.; Coimbra, C.E.A., Jr. Indigenous fire ecologies, restoration, and territorial sovereignty in the Brazilian Cerrado: The case of two Xavante reserves. Land Use Policy 2021, 104, 104055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monterroso, I. Comunidades locales en áreas protegidas: Reflexiones sobre las políticas de conservación en la reserva de Biosfera Maya; CLASCO: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ramón, C.M.; Villacís, M.A.T.; García, A.E.C. Tortugas Charapa un aporte para el turismo comunitario y conservación de la biodiversidad. Explor. Digit. 2020, 4, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveda-Rodríguez, A.; Cueva, R.; Zapata-Ríos, G. Space use of yellow-spotted river turtles (Podocnemis unifilis) in Yasuni National Park, Ecuador. Chelonian Conserv. Biol. 2018, 17, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weckmüller, H.; Barriocanal, C.; Maneja, R.; Boada, M. Factors Affecting Traditional Medicinal Plant Knowledge of the Waorani, Ecuador. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cueva, R. Diagnóstico de los Recursos Naturales en el Territorio de Seis Comunidades Kichwas Asentadas en la Zona Noroccidental del Parque Nacional Yasuní, Río Napo, Orellana-Ecuador. Wildl. Conserv. Soc. 2005, 1, 3–34. [Google Scholar]

- Bárcenas-García, A.; Michalski, F.; Gibbs, J.P.; Norris, D. Amazonian run-of-river dam reservoir impacts underestimated: Evidence from a before–after control–impact study of freshwater turtle nesting areas. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2022, 32, 508–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escalona, T.; Valenzuela, N.; Adams, D.C. Do Local Environmental Factors and Lunar Cycle Influence Timing and Synchrony of Oviposition of a Turtle with Strict Nocturnal Nesting? Diversity 2019, 11, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harju, E.; Sirén, A.H.; Salo, M. Experiences from harvest-driven conservation: Management of Amazonian river turtles as a common-pool resource. Ambio 2018, 47, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisemberg, C.C.; Vogt, R.C.; Balestra, R.A.M.; Reynolds, S.J.; Christian, K.A. Don’t put all your eggs in one basket—Lessons learned from the largest-scale and longest-term wildlife conservation program in the Amazon Basin. Biol. Conserv. 2019, 238, 108182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, D.; Peres, C.A.; Michalski, F.; Gibbs, J.P. Prospects for freshwater turtle population recovery are catalyzed by pan-Amazonian community-based management. Biol. Conserv. 2019, 233, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escalona, T.; Adams, D.C.; Valenzuela, N. A lengthy solution to the optimal propagule size problem in the large-bodied South American freshwater turtle, Podocnemis unifilis. Evol. Ecol. 2018, 32, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.Y.; Li, L.; Li, S.K.; Sun, H.H.; Bi, G.Q. Characterization of the complete mitochondrial genome of Podocnemis expansa (Pleurodira: Podocnemididae). Conserv. Genet. Resour. 2018, 10, 479–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pignati, M.T.; De Souza, L.C.; Mendes, R.D.; Lima, M.D.; Pignati, W.A.; Pezzuti, J.C.B. Levels of organochlorine pesticides in Amazon turtle (Podocnemis unifilis) in the Xingu River, Brazil. J. Environ. Sci. Health B 2018, 53, 810–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway-Gómez, K.; Reibel, M.; Mihiar, C. A predictive model of yellow spotted river turtle (Podocnemis unifilis) encounter rates at basking sites in lowland eastern Bolivia. Appl. Geogr. 2014, 53, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, L.L.; Mertins, O.; Gama, G.S.; Fernandes Patta, A.C.M.; Mathews, P.D. A new Myxidium species (Myxozoa: Myxosporea) infecting the gallbladder of the turtle Podocnemis unifilis (Testudines: Podocnemididae) from Peruvian Amazon. Acta Trop. 2017, 172, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Leão, S.P.; Famelli, S.; Vogt, R.C. Home Range of Yellow-Spotted Amazon River Turtles (Podocnemis unifilis) (Testudines: Podocnemididae) in the Trombetas River Biological Reserve, Pará, Brazil. Chelonian Conserv. Biol. 2019, 18, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, D.T.M.T.O.; de Sousa Correia, J.M.; Rameh-de-Albuquerque, L.C.; dos Santos, E.M. Record of exotic species yellow-spotted river turtle (Podocnemis unifilis podocnemididae) in a conservation unit in northeastern Brazil. Herpetol. Notes 2019, 12, 87–89. [Google Scholar]

- Gentil, E.; Bezerra, B.; De Medeiros, L.A.; Barnett, A.A. Predation by white-fronted capuchin monkeys, Cebus albifrons on eggs of three species of freshwater turtles in Brazilian Amazonia: Solitary nests are also depredated. J. Nat. Hist. 2021, 55, 1983–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, C.J.; Macey, S.K.; Blair, M.E.; Sterling, E.J. Assessing Ecological and Social Dimensions of Success in a Community-based Sustainable Harvest Program. Environ. Manag. 2021, 67, 731–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reig, M.C. De lagos propios a Patrimonio de la Nación. Disputas por el espacio acuático en la Reserva Nacional Pacaya Samiria. Rev. Antropol. Soc. 2017, 26, 281–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintana-Arias, R.-F. El manejo del mundo naturaleza y sociedad: Visión del conflicto ambiental desde la concepción y el manejo del medio natural de una comunidad indígena colombiana. Rev. Luna Azul 2017, 45, 353–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirano, L.Q.L.; da Alves, L.S.; Menezes-Reis, L.T.; Dos Santos Mendonça, J.; Simões, K.; Santos, A.L.Q.; Vieira, L.G. Effects of egg exposure to atrazine and/or glyphosate on bone development in Podocnemis unifilis (Testudines, Podocnemididae). Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 182, 109400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fachín Terán, A.; Von Mülhen, E.M. Reproducción de la taricaya Podocnemis unifilis troschel 1848 (testudines: Podocnemididae) en la várzea del medio solimões, Amazonas, Brasil. Ecol. Apl. 2003, 2, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barroso, W.A.; de Moura, N.A. Etnoconhecimento morfológico e ecológico de quelônios (Podocnemis expansa e P. unifilis) em uma comunidade ribeirinha. Biota Amaz. (Biote Amaz. Biota Amaz. Amaz. Biota) 2016, 6, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fierro, D.; Salvador, P.; Terneus, E. Estimación de la proporción de sexos de neonatos de tortuga charapa (Podocnemis unifilis) mediante morfometría del caparazón, en la Amazonía ecuatoriana. Espíritu Emprend. TES 2018, 2, 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestanza-Ramón, C.; Capa, M.S.; Garcia, A.C.; Gutierrez, M.J.; Villacís, M.T.; Velasco, A.A. Community Tourism In Ecuador: A Special Case In The Rio Indillama Community, Yasuní National Park. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. 2019, 8, 653–657. [Google Scholar]

- Casal, A.C.; Fornelino, M.M.; Restrepo, M.F.G.; Torres, M.A.C.; Velasco, F.G. Uso histórico y actual de las tortugas charapa (Podocnemis expansa) y terecay (Podocnemis unifilis) en la Orinoquia y la Amazonia. Biota Colomb. 2013, 14, 45–64. [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa Forero, I.C. Saber Local, Uso y Manejo de las Tortugas Charapa Podocnemis Expansa y Taricaya Podocnemis unifilis (Testudines: Podocnemididae) en el Resguardo Curare-Los Ingleses. La Pedrera: Amazonas: Colombia. Sede Amaz. 2010. Available online: https://repositorio.unal.edu.co/bitstream/handle/unal/9601/ilbacarolinafigueroaforero.2010.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 18 April 2022).

- Meza Salcedo, G. Ética de la investigación desde el pensamiento indígena: Derechos colectivos y el principio de la comunalidad. Rev. Bioética y Derecho 2017, 41, 141–159. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).