1. Introduction

A significant fraction of rural households in low- and middle-income countries, particularly of sub-Saharan Africa, have no access to piped water in their neighbourhood [

1,

2]. There are long walking distances to collect water, as well as cooking fuel, especially from an “improved” source of water for potable use and other household activities. The collection of water and cooking fuels can be a considerable physical and economic load that particularly impacts on women and mainly female children [

3,

4,

5]. Households linked to water collection journey times of greater than 30 min commonly collect progressively less water [

6,

7]. Restricted water and energy availabilities often lead to a reduction in the amount of water and energy that are used for drinking, hygiene, and cooking in the household.

Residents’ access to clean potable water and cooking fuels is imperative for appropriate development, and addressed in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [

8]. The Joint Monitoring Program of the World Health Organization on water highlights that “Access to drinking water means that the source is less than 1 km away from its place of use and that it is possible to reliably obtain at least 20 L per member of a household per day.” [

1]. For the post-2015 SDGs, access to basic drinking water is defined as “using an improved source with a total fetching time of 30 min or less for a round trip including queuing” [

9].

Access to good-quality water and a clean energy supply is an essential requirement for the reduction of poverty, and sustainable human development [

10,

11,

12]. Despite impressive accomplishments towards sustainable access to safe water and clean energy sources, billions of people still lack access to sustainable resources nowadays. The Joint Monitoring Program (JMP) states that 26% of the global population (2.6 billion people) safely manages potable water, and that 2.3 billion people reside in water-stressed regions of the world [

13]. Furthermore, at least 20% of the global population (about 1.4 billion people) are still denied access to electricity sources, and around 40% of the global population (roughly 2.7 billion people) depend on traditional biomass as their major source of energy for cooking [

14]. Universal sustainable access to both clean water and energy are key priorities of the global development agenda, which is the foundation for the SDGs. Without sustainable water and energy provisions, large proportions of the world’s population are denied access to essential amenities. As a consequence, the poor are forced to live and work in unhealthy circumstances.

Two-thirds of the world’s poor people are female. They typically reside in water-scarce regions, with limited access to a secure and permanent supply of water for productive and household uses [

15]. The majority of these poor people rely on agriculture for their livelihood, and reside in regions of south Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. These areas are linked to the world’s water-poorest communities [

16].

The SDGs were unanimously accepted by the member states of the United Nations in September 2015, providing a comprehensive framework for global cooperation to achieve a sustainable prospect for the planet. The 17 SDGs and their 169 targets define a path to fight long-standing inequality and injustice, end extreme poverty, and protect the planet’s environment. Sustainable access to clean water and energy, as well as gender equality, are central to the success of the SDGs. The global goal on water (SDG6) consists of key elements such as ensuring availability to clean water and safe sanitation for all, as well as safe and affordable drinking water. The global goal on energy (SDG7) comprises three key targets: affordable, reliable, and common access to contemporary energy services; a substantial share of renewable energy in the overall energy mix; and doubling up the rate of improvement in global energy productivity [

17]. It is imperative to highlight that inequality in accessing water and energy resources is intensified among some communities. For instance, women in rural communities often represent a marginalized group, which is unjustifiably burdened with inaccessibility to good-quality water and clean energy sources [

13]. Females excessively serve as water and energy suppliers, collecting water and cooking fuels across many households. Frequently, women and girls need to walk long distances to fetch water and energy supplies [

18].

Consequently, in low- and medium-income countries, water and energy inaccessibility is typically characterized by insufficient household access to both good-quality water and energy sources. This is particularly the case for electricity, leading to a reliance on unimproved water sources and unclean fuels for heating, cooking, and lighting, which can be harmful for human health and welfare [

13,

19,

20,

21,

22].

Concerning the gender dimension, the understanding of ‘gender’ by the authors needs to be defined in the context of this article. The authors agree with Risman [

23], and view gender as a social structure that identifies and legitimatizes certain behaviours, roles, and responsibilities as masculine or feminine, which is subsequently linked to social actions. As people usually act in accordance with their predefined gender roles, the social structure is remodelled [

24]. Gender is typically associated with differences in what people can actually perform, the services and resources they may access, and their potentials and prospects for their own development [

25]. Concerning the study region in rural Nigeria, gender is traditionally seen as binary. However, the authors are aware of, and accept, a more modern view of gender as not being binary.

There are considerable inter-linkages between water, energy, gender, and health-worsening imbalances among females, which cause health challenges. Amid other challenges, inaccessibility to safe and sufficient water, as well as clean energy, increases the risk for related waterborne and respiratory illnesses including, for example, cholera, which is a bacterial infection transmitted by polluted water, and cardiovascular illnesses, due to indoor air pollution [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. Considering the position of females in providing water and energy for their households, women and girls are particularly exposed to the contraction and transmission of several diseases [

26,

30].

A number of conceptual frameworks of vulnerability are significant for directing multiple disciplines [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]. To evaluate the various vulnerabilities experienced, the study used the vulnerability concept, based on resource accessibility. This refers to a state of being exposed to the possibility of being assaulted, or otherwise harmed, either emotionally or/and physically, due to an incapacity to protect affected individuals’ personal interests in the course of resource accessibility [

36,

37,

38].

Since 2015, gender equality and the empowerment of women are seen as crucial in attaining the SDGs. Adhering to these development obligations, a considerable number of studies focus on the impacts of inequality experienced by females, with women and girls regularly experiencing a greater proportion of the detrimental effects of water and energy inaccessibility. However, limited work has been undertaken on the interaction between gender, water, and energy at the household level, particularly in rural areas. Remarkably, the Sustainable development Goals (SDGs) highlight the significance of equal rights to resource accessibility across gender in target 5.a. Thus, water and energy are crucial resources, which women should have the same right to as their male counterparts. Moreover, the importance of ending all forms of gender-based discrimination against women is enshrined in target 5.1 of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [

39]. The series of connections between gender, water, and energy arise from the conventional roles played by women and girls on a household scale, which includes the collection of water and cooking fuel, as well as cooking [

40].

Across several nations, women are prohibited from working, for social and cultural reasons. According to the World Bank, there are over 100 economies with labour regulations that limit the types of employment women can embark on, as well as where and when they are allowed to work [

41]. It further assesses that this has an effect on the employment options of about three billion women. Furthermore, the report points out that 18 countries give husbands legitimate rights to prevent their spouses from working. Correspondingly, International Labour Organization (ILO) reports disclose that 14% of the women in Africa are household workers, and women represent an estimated 83% of household workers globally [

42]. In 2018, the work force involvement rate of women was 48%, in contrast with that of men, which was 75% in the matching year [

43]. This situation is more common in rural areas of Nigeria, where more than 50% of Nigerian women reside [

44]. Despite the gender-based employment marginalisation faced by women in many regions of the world, studies show that women contribute immensely to households’ resources accessibility. Studies [

45,

46] reveal that women in many rural Nigerian households contribute significantly from what they earn towards running daily activities, and securing households’ food security [

45,

46].

Individual constituents (either water or energy) are examined in some research projects. For instance, other studies [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30] assess individual elements, such as water or energy, as a separate entity. Pouramin et al. [

26] find that females experience barriers towards accessing basic water provisions. They discover that women, due to their responsibilities as water providers, are at risk of exposure to polluted water, thereby suffering from various negative health effects. Wu [

29] investigates the influence of the choice of household cooking energy source on female’s health from various dimensions, including health and common activities. The study intends to assess energy transition and health enhancement concerning developing countries. Findings for individual households indicate that cooking energy selection switches from solid fuel to clean energy sources, which improves female health.

Regardless of these gender-related inequalities, research evaluating the intersection between gender on one side, and water and energy on the other, is still in progress. Successfully addressing gendered water–energy inequities requires considerable focused resources. Thus, this study aims to examine women’s accessibility to households’ water and energy; it also explores the various vulnerabilities experienced due to water and energy collection in rural areas of Katsina State, northern Nigeria.

This research article is structured in the following way: after a concise overview and a critical review of the scientific literature related to water–energy accessibility in

Section 1,

Section 2 summarises the methodology covering a description of the materials and methods applied to conduct the work, which involves the description of the study area, conceptual framework, a selection of the rural surveyed communities, as well as statistical analysis of the data.

Section 3 is devoted to the results, highlighting socio-economic characteristics of the female household heads, access to water and energy across the identified income groups, physical distances covered, and time taken to collect water and cooking fuel. Moreover, key findings are discussed in

Section 4.

Section 5 concludes on the main results, and emphasizes the wider importance of this work. Finally,

Section 6 summarises limitations and recommends future studies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area Description

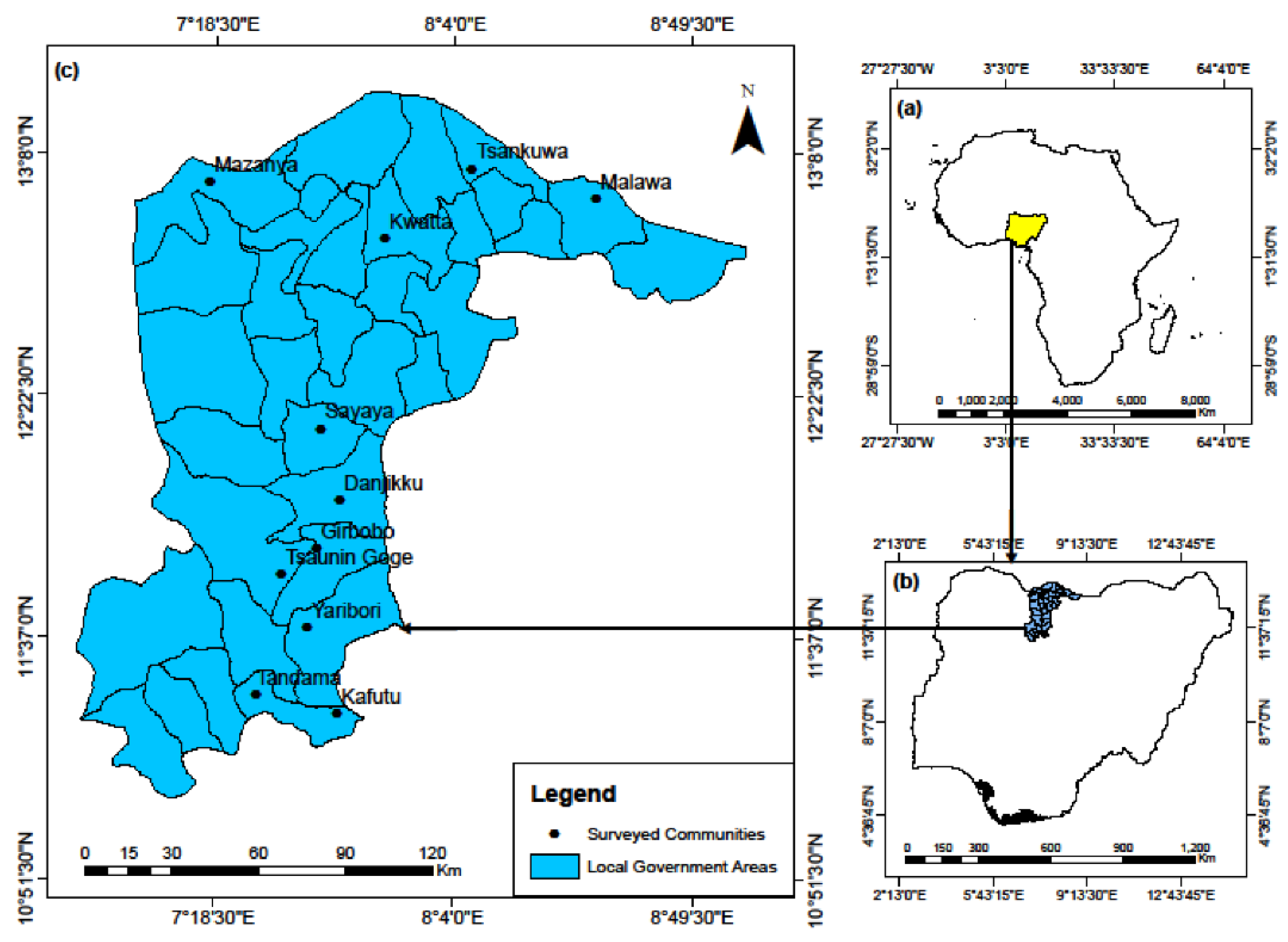

The project was carried out in Katsina State, located within latitude 11°08′ N and 13°22′, and longitude 6°52′ E and 9°20′ E, with an area of about 24,000 km

2 (

Figure 1). The state consists of 34 local government areas. The average literacy proportions are 59% for males, and 29% for females. In 2019, 56.42% of people in the state were below the poverty threshold [

47]. The state population estimated census data released by the National Population Commission states that the total population for the year 2021 was 9,145,600, of which 4,664,256 (51%) and 4,481,344 (49%) were males and females, respectively.

The map of the study region highlighting the surveyed communities was created using a geographical information system application and subsequent cartographical analysis. Global positioning system coordinates of the sampled communities were noted during the field study, and integrated into the existing digital map database, accessible at the Geographical Information System and Remote Sensing Unit (Department of Geography, Umaru Musa Yarádua University).

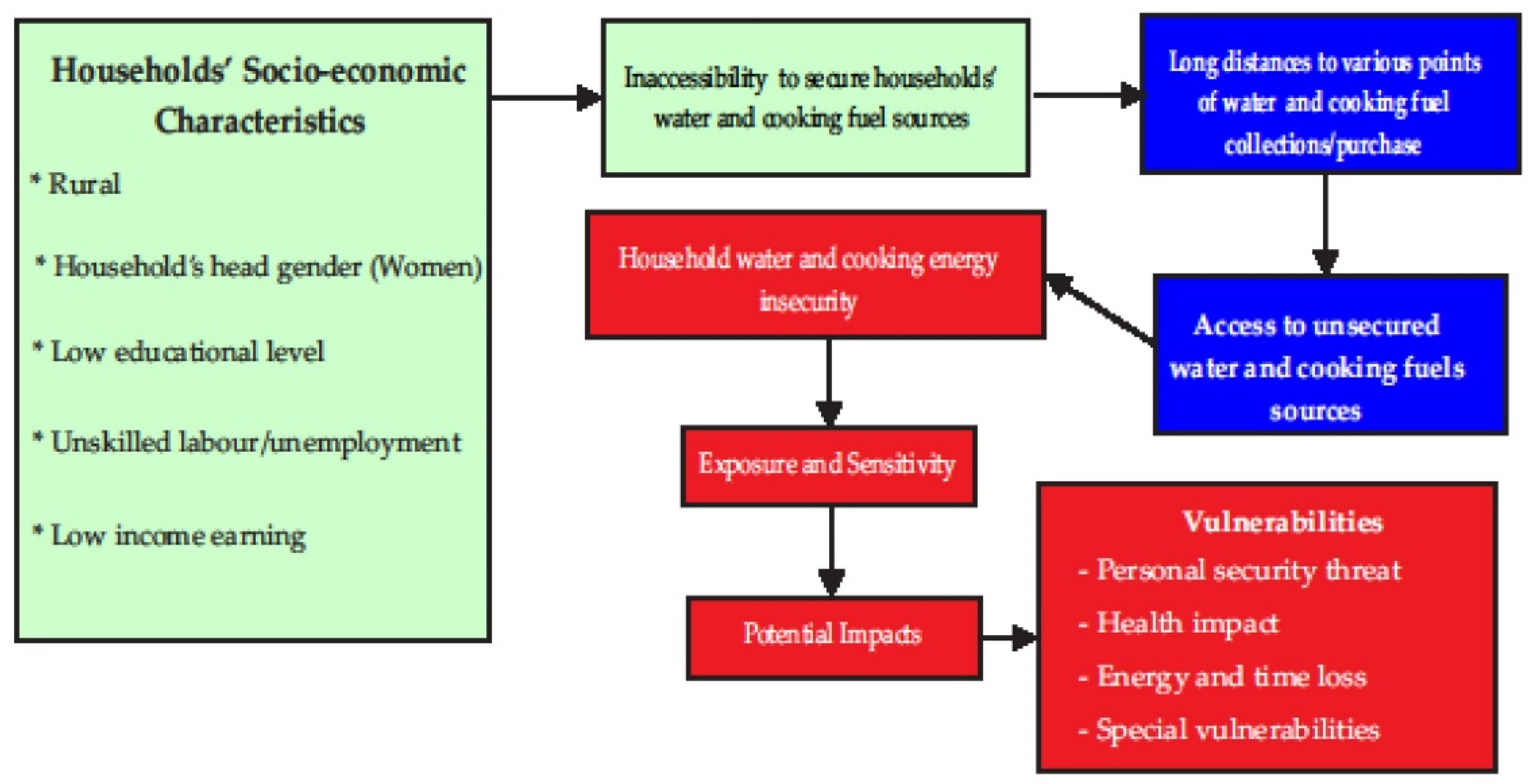

2.2. Conceptual Framework

To investigate the inter-linkages between gender and accessibility to households’ resources (water and energy), and to understand the different intensities of vulnerabilities as a result of water and cooking energy accessibility among rural, women-headed households, a conceptual framework for the study was designed. In rural, women-headed households of low- and medium-income countries, water and energy insecurities typically manifest themselves as a deficiency in household access to both safe drinking water and cooking fuels, leading to a reliance on unclean water and cooking fuels (biomass), which can be detrimental for health and well-being.

Fetching water and gathering biomass is commonly the responsibility of females. They can be asked by their husbands to perform this task for many hours per day, resulting in less productive time and energy for formal employment, education, as well as social and political interactions in public. Water and cooking fuel (biomass) collections may also be unsafe, due to grievances from carrying heavy loads and other health impacts (see above). In some contexts, women also face an increased exposure to both physical and sexual attacks. Consequently, old-fashioned gender divisions of household labour mean that females commonly spend considerable time at home, and prepare almost all household meals. This leaves females more vulnerable to the negative impacts of indoor air contamination and accidents. The associated impacts are felt disproportionately between males and females, with women experiencing a higher percentage of the harmful effects of water and energy insecurity.

2.3. Research Design

The study was designed based on the conceptual framework, illustrated in

Figure 2, to explore women’s access to households’ water and cooking fuels, as well as the associated vulnerabilities experienced by accessing these resources. A semi-structured questionnaire was specifically designed for this study, including a socio-economic section, and questions about the physical and economic access to water and energy sources, as well as the considerable vulnerabilities and burdens experienced by females in rural communities. The focus was on conditions linked to water and cooking fuel accessibility, considering particularly the unequal dangers, physical security threats, and health risks, as well as time and energy losses, linked with water and energy access.

In order to explore the characteristics of socio-economic classification, the collected information included household heads’ educational level, monthly income, and occupation. To understand the accessibility to water and energy sources, respondents were first questioned about the leading sources of drinking water and cooking energy in the surveyed area. Sources specified were grouped into enhanced and unimproved water sources [

48]. The improved sources are piped water into dwelling, piped water to yard, public tap/standpipe, borehole/tube well, protected dug well, protected spring, and rainwater; original water sources are unprotected spring, unprotected dug well, cart with tank or drum (water vending), tanker truck, and surface water.

The cooking energy sources were also categorised, based on the World Health Organization (WHO) [

49], into clean and unclean fuels. The clean fuel sources are electricity, natural gas, liquefied petroleum gas, ethanol/methanol, and kerosene; the unclean sources are coal, charcoal, sawdust, fuelwood, agricultural residue, and animal dung. To measure the distance covered to access various water sources, and the time taken to collect the corresponding water, WHO and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) recommend thresholds of 1000 m and 30 min, respectively [

18]. The authors adopted these values in this study for categorisation purposes.

2.4. Selection of the Surveyed Households

A qualitative study design was carried out in Katsina State. The state has been stratified into urban and rural areas. Hence, this format was adopted in selecting ten surveyed communities that were chosen considering rural norms [

50]. The selected surveyed rural communities are Mazanya, Tsankuwa, Kwalla, Malawa, Sayaya, Danjanku, Girbobo, Tsaunin Goge, Tandama, Yari bori, and Kafutu, as indicated in

Figure 1.

Only households that are headed by a female were considered for the study. Respondents were questioned on the estimation of distance and time taken for a round trip to fetch water, quantity of water collected from the various sources, availability of cooking fuels at the point of purchase or collection, and who is responsible for water and energy collections. Information on vulnerabilities such as personal security threats, health impact of the water and energy collection trip, and energy and time loss, as well as special vulnerabilities, were also gathered and analysed.

2.5. Data Collection

Primary and secondary sources of data were applied for this study. The primary data were generated through the structured questionnaire administration. The survey was conducted in person by ten field assistants, who are conversant with the surveyed rural communities.

Data were collected over a period of one month (between mid-March to mid-April 2022). Due to unavailable data on the number of female-headed households in the study area, the number of households surveyed is a reflection of the available female-headed households across the surveyed communities. Mazanya has 11.8% of the surveyed households (65 households), Sayaya has 12.7% (70 households), Kwalla and Malawa each have 10.2% (56 households each), Danjanku has 9.1% (50 households), Tsankuwa has 7.3% (40 households), Girbobo has 7.6% (42 households), Tsaunin Goge has 9.5% (52 households), Tandama has 8.4% (46 households), and Kafutu has 6.7% (37 households). Finally, Yari bori, which represents 6.5% of the surveyed households, has 36 households. At the end of the exercise, 550 copies of questionnaires were served to the female-headed households across the selected rural communities.

2.6. Statistical Data Analysis

IBM SPSS version 24 was applied for data entry and analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to assess the household heads’ socio-economic and demographic variables, as well as their access to various water and energy sources. Summary statistics in terms of proportions, expressed in percentages, were calculated. To determine the association and direction of the water and energy crisis, the Pearson product-moment correlation (PPMC) was employed to determine the relationships between the socio-economic variables of the female household heads. The corresponding key variables are educational status and monthly income. Simple bivariate correlations were adopted. Chi-square tests of independence were undertaken, to determine whether there is relationship between access to households’ water and energy and the households’ income groups. The authors only considered a minimum degree of significance at 95% confidence level (p = 0.05).

4. Discussion

This investigative study adds hard data evidence to the ongoing discussion towards achieving sustainable equitable access to clean water and energy, regardless of gender, socio-economic status, or location in sub-Saharan, rural African settings. Ending all forms of discrimination against women is not only a fundamental human right, but is central for the sustainable future of these regions. Empowering women and girls helps economic growth and development. Thus, ensuring equitable rights to economic resources and accessibility to household resources, which include water and energy, is key to empowering women.

The study observes that physical and economic inaccessibility to good-quality water and clean energy is prevalent in many of the surveyed rural households. Poor water and energy access is more widespread in low-income households, whereas poor accessibility to these essential household resources is associated with various vulnerabilities experienced across the affected households.

The investigation, across 550 households headed by females, reveals a low level of household head education, which implies that women are denied access to the same education as men. The study also reveals that the relationship between the educational status of female household heads with their various income groups is strong. In addition, high-income households with a household head with a relatively higher educational level tend to have easy access to enhanced water and clean energy sources. This finding reveals the water access situation where low-income households have access to various unimproved water sources. Consequently, the study shows the prevalence of access to different sources of unclean (solid) cooking fuels across the surveyed households. This is directly associated with a low-income level and location. Previous articles indicate that income is important for rural household water and energy preferences in developing states [

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60].

The results show that the accessibility to various water sources, availability of fuels, and the various distances to either points of collections or purchases varies across the investigated households. Several households (52.8% of the surveyed households) obtain water by walking more than 1000 m from their households, which coincides with some studies conducted in other sub-Saharan African countries [

61,

62]. The distances are above the maximum threshold recommended by WHO and UNICEF [

18].

The study further reveals the frequent unavailability of many high-value fuel sources from local supplies, which include cooking gas, kerosene, charcoal, and saw dust, across the surveyed rural communities. This can be explained by poorly developed markets and distribution problems [

63]. Conversely, households that access low-value energy sources made of biomass, which include dung, agricultural residue (post-harvest waste), and fuelwood, find these readily available either at the point of collection or via purchase.

The findings support international investigations by Rahut et al. [

54] and Zhou et al. [

64] in rural households of Pakistan and northern China, respectively. They find that the availability of biomass energy sources in the respective rural households are a major factor in energy choice. Furthermore, Gaur [

57] finds that in rural areas of India, closeness to the market is one of the reasons that positively affects domestic use of modern fuel sources.

The study reveals the average distance travelled and time taken to collect water from various sources remains high for most households, which indicates that a large proportion of women and children live in families where the burden of collection is both over 1000 m and 30 min, which means that the distance covered and time taken are higher than the respective WHO and UNICEF thresholds for a safe journey [

18]. Consequently, the study finds that rural women and children spend unreasonable time periods collecting cooking energy sources. This finding is supported by Heltberg [

65], who finds that household responses to fuel scarcity leads to increased fuel collection times in rural India.

Moreover, the findings reveal that the majority of the surveyed households travel long distances to collect water and cooking fuels. On their daily trips to collect water and cooking fuel, rural women across the investigated households are vulnerable to dangers threatening their personal security. As the water and cooking fuel collection sources are located at various different places away from their households, women and children commonly walk very long distances, and have to trek via unsecured paths, often on their own and defenceless. Women and girls fetching water and cooking fuel everyday often became the target of threats to their personal security, sexual violence, and physical attacks.

Pommells et al. [

66] report that travelling long distances, intensified by the regularity of community women’s water-fetching habits, gives attackers the chance to target women who are alone, isolated, and defenceless. In addition, other studies [

66,

67,

68] reveal that beyond the physical threats, which include sexual assaults, women are also subjected to psychological stress linked to panic attacks and general anxiety, intensified by the lack of confidence among females. On the same paths to water and fuel collection locations, physical violence linked to animal attacks is also reported [

66,

67,

69]. Sharing the same water resource and foot paths with dangerous hungry animals also contributes to physical insecurity.

The study reveals that women and children collecting large quantities of water and cooking fuel multiple times per day report considerable physiological health impacts attributed to their trips. These health impacts are outside of those linked to water quality or safe cooking fuel. Women are often executing collection activities from an early age when good physical development is critical. Other studies [

69,

70] state that adverse health impacts linked to collecting water and cooking fuels include lasting back injuries, fatigue, micronutrient shortages due to a high number of calories being burned, body parts scratched and wounded by shrubs, attacks by wild dogs, and bites by venomous snakes.

Combining health effects with security fears, a broader scope of health risks appear. As an example, sexual attacks may not only damage the attacked person physically and psychologically, but may also result in long-term sexually transmitted diseases, such as the human immunodeficiency virus, potentially leading to the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Animal strikes are also a considerable health threat. Inflicted injuries are either hard to cure in remote rural locations and/or are liable to infection, potentially leading to mortality. The consequential health effects as a result of these experiences not only damage the physical advancement of women and children, but also obstruct their capability to take part in or achieve other daily activities and tasks, which include school education and professional work. As a consequence, some women remain uneducated, and without qualified jobs.

While collecting water and fuels for various household activities including cooking, hygiene, drinking, cleaning, and other fundamental actions is not a waste of time, the way in which most women and children across the investigated households fetch the resources often pose a great loss of time for them. In most of the surveyed households, access to water and cooking fuel sources is remote. It follows that women spend many hours making their daily collection round trips. The time spent could be used differently, for other productive or recreational activities.

The challenges highlighted in this study are also common to other rural settings, for example in Somalia, where women devote an average of 11.3 h weekly to the fetching of water [

68]. The time spent on water and cooking fuel collection is accompanied by an opportunity cost [

5], linked to ‘trade-offs’ [

68]. Fetching water, collecting fuelwood, and other household responsibilities performed by women cause trade-offs including reduced security, nourishment deficiencies, and insufficient schooling [

68].

In addition to time loss, the intensity of energy required to carry out water and fuel collections leaves little energy to accomplish other productive pursuits in the remaining daytime hours. Therefore, enhancing access to water, as well as cooking fuel, and reducing the distant trips to collect water and fuel allows women to participate in other productive activities, such as education and professional work.

This study reveals the influence of various income groups on access to household resources. For instance, high-income groups are linked to a lower average distance to the water sources than the other groups. However, this is not the case for collecting water from improved sources. The insecurity is related to the time taken and distance covered, which show the vulnerability of all respondents, regardless of their income group. There is a very high level of health concern common to all individuals who need to walk more than 1000 m to a water source, or require more than 30 min for total collection time.

The research reveals that across all investigated households, rural women and children are exclusively accountable for the collection of water and cooking fuels. Geere and Cortobius [

68] also highlight that the women and children are principally in charge of fetching water. Moreover, women with special vulnerabilities are at an even greater disadvantage in accessing water. The study indicates that older adults, pregnant women, orphans, individuals with long-term illnesses, disabled females, and women coping with social stigma are in a more difficult position to access, and subsequently carry, water. It follows that these people are especially vulnerable, and their households face severe water insecurity [

66,

68]. Respondents report that pregnant women are extremely exposed to water uncertainty because of their physical constraints in undertaking the water collection activities. These groups have diverse physical or incidental constraints, and their incapability to perform the trip of water collection effectively broadens the challenge of inequitable access to water sources. This may either force them to take more dangerous journeys to other water resources, reduce their opportunity to successfully meet their basic needs for water, or force them to make other more costly arrangements.

The study findings reveal that it is a major role of women to collect cooking fuel across the investigated households; this coincides with the findings of the African Development Bank [

69], which indicate that the typical rural energy predicament is linked to traditional gender role separation, with women spending considerably more time than men addressing energy supply needs for family survival [

71]. This renders them vulnerable to wounds, including attacks by feral animals [

70]. Moreover, addressing the challenges of women’s access to water and energy is critical towards achieving SDGs 5, 6, and 7. Females are disadvantaged concerning water and energy governance in rural societies in sub-Saharan Africa, because they are not participating in the decisions concerning water and energy access, control, and utilisation. In order to proceed positively on SDG 6.B (“stakeholders participation”) and SDG 7.1.2 (“proportion of population with primary reliance on clean fuels and technology”), a clear focus on addressing SDGs 5.1 (“end all forms of discrimination against all women and girls everywhere”), 5.2 (“eliminate all forms of violence against all women and girls in the public and private spheres, including trafficking and sexual and other types of exploitation”), and 5.5 (“ensure women’s full and effective participation and equal opportunities for leadership at all levels of decision-making in political, economic and public life”) is required [

17]. Therefore, it is necessary to include women in local water and energy management decision-making, in order to lessen discrimination and violent behaviour linked to water and energy collection.

The struggles faced by rural women can be addressed if there is improved ownership by women, and a reduction in power held by men who traditionally manage key components of the household income, which also concerns water and energy management. Safeguarding women, so they have the same opportunities as men, would encourage them, and add invaluable understanding to basic processes that they are personally connected to, such as water and energy organisation.