Sustainability-Related Strategic Evaluation of Business Models

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

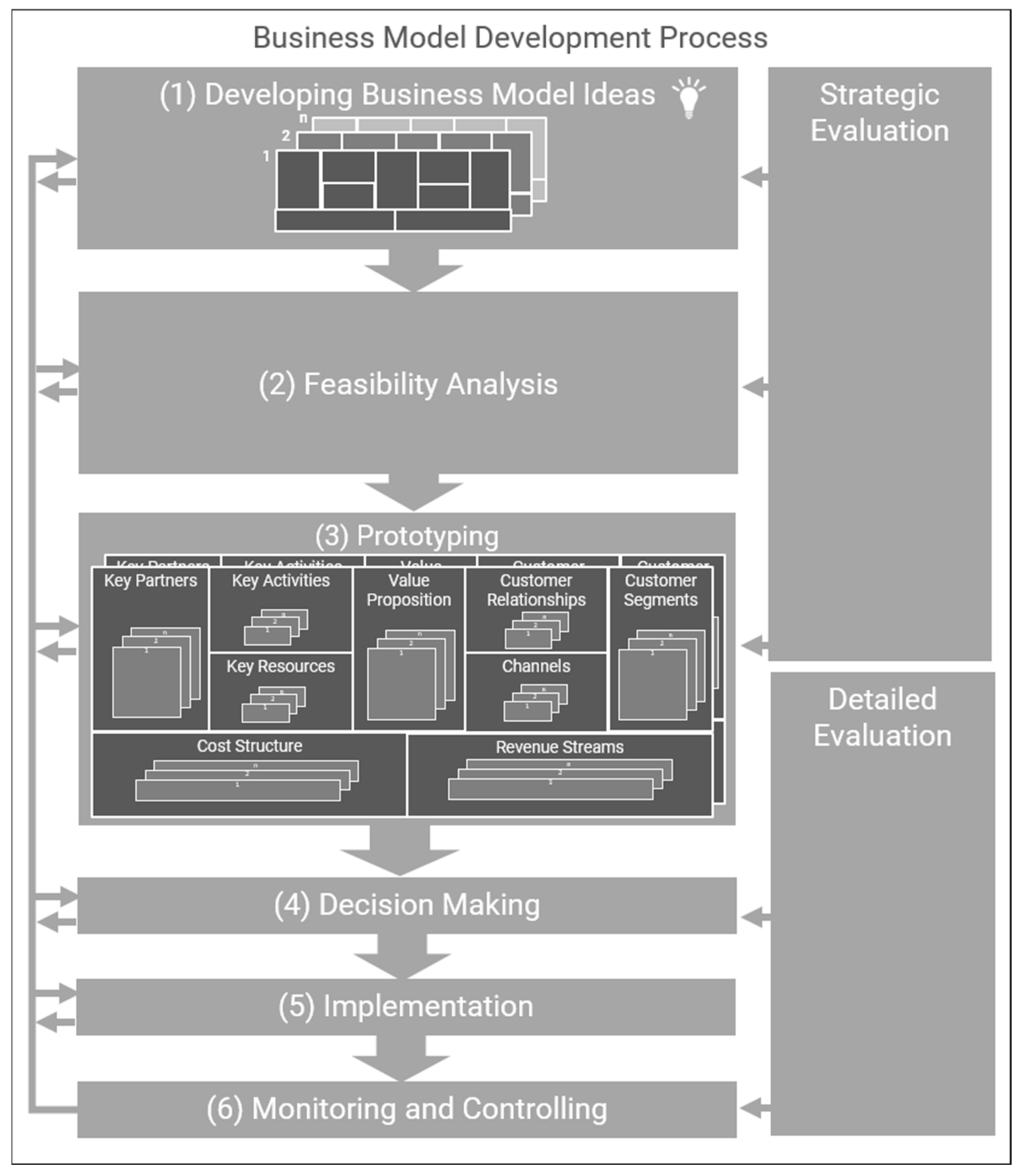

2.1. Business Models, Their Development and Their Evaluation

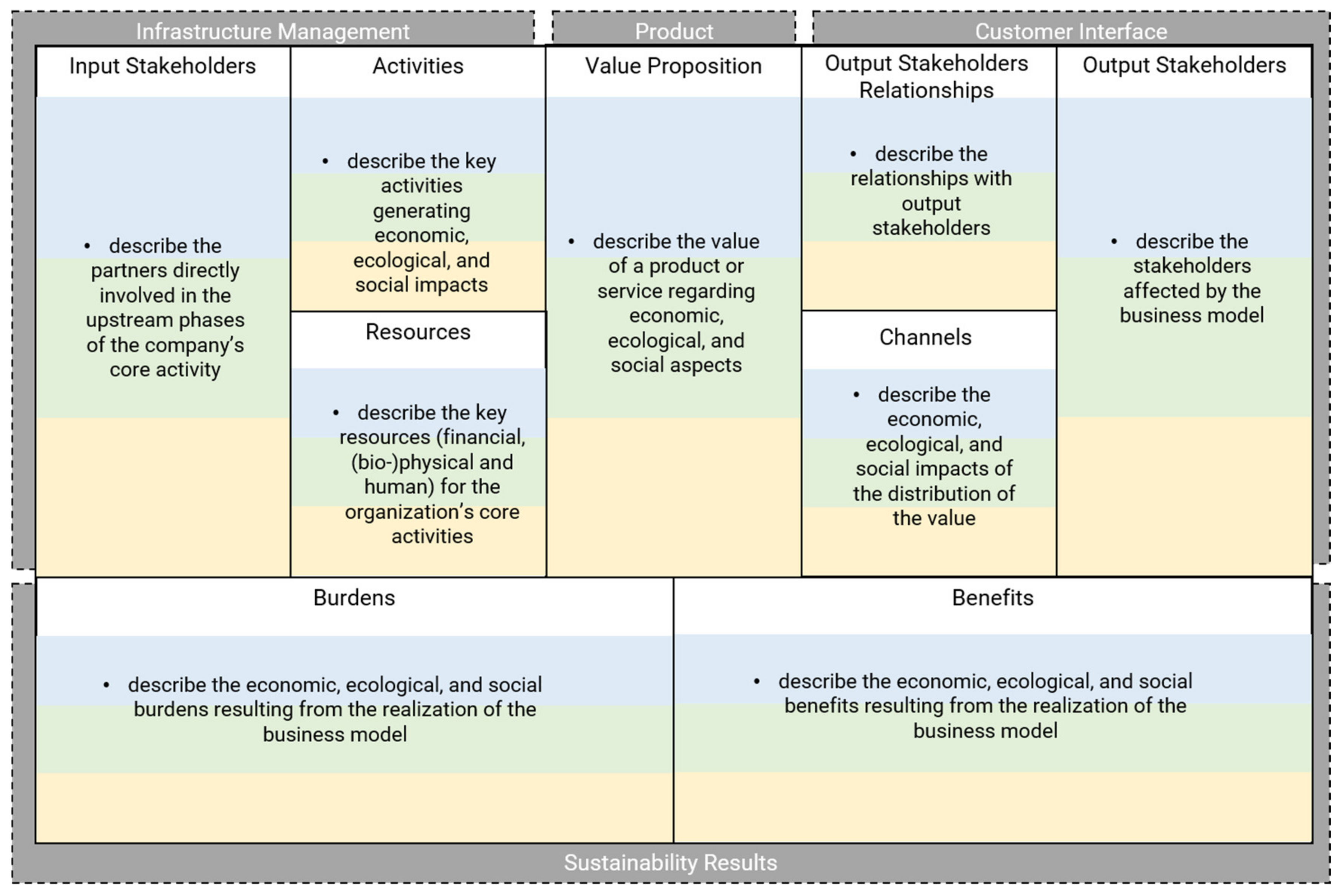

2.2. Sustainable Business Models, Their Development and Their Evaluation

3. Methods

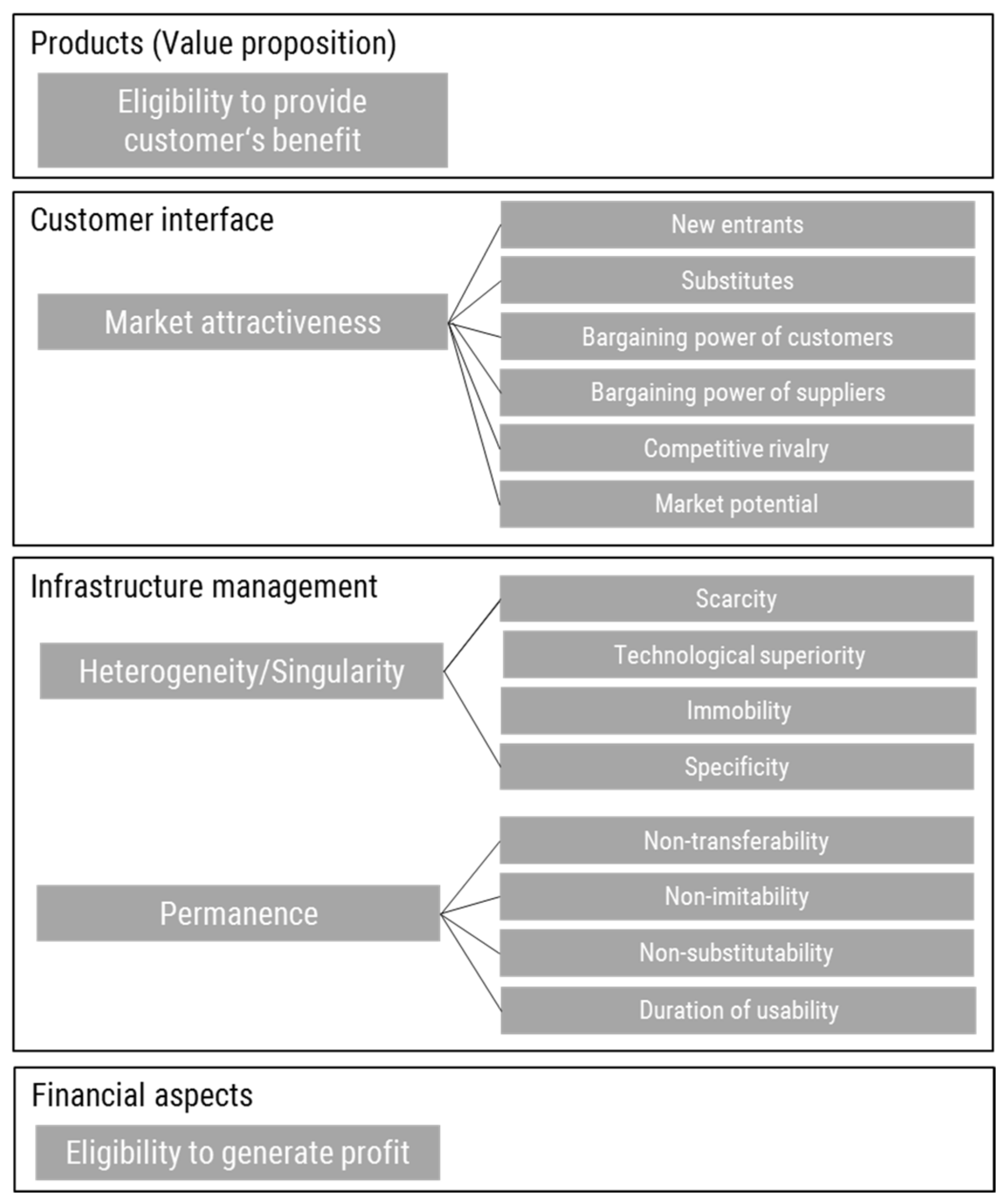

3.1. Developing Criteria for a Strategic Evaluation of Business Models

- Value: Is a company able to react to environmental opportunities/threats with the assistance of its resources?

- Rarity: Do only a few companies have the control over a resource?

- Imitability: Does a company face a disadvantage by obtaining a resource it does not have but competitors have?

- Organization: Is a company organized in a way that enables exploiting the potential of its resources and capabilities?

- Eligibility of providing customer benefits/value;

- Heterogeneity;

- Permanence;

- Eligibility to generate profit.

3.2. Including Sustainability Aspects within the Strategic Evaluation Criteria

4. Results

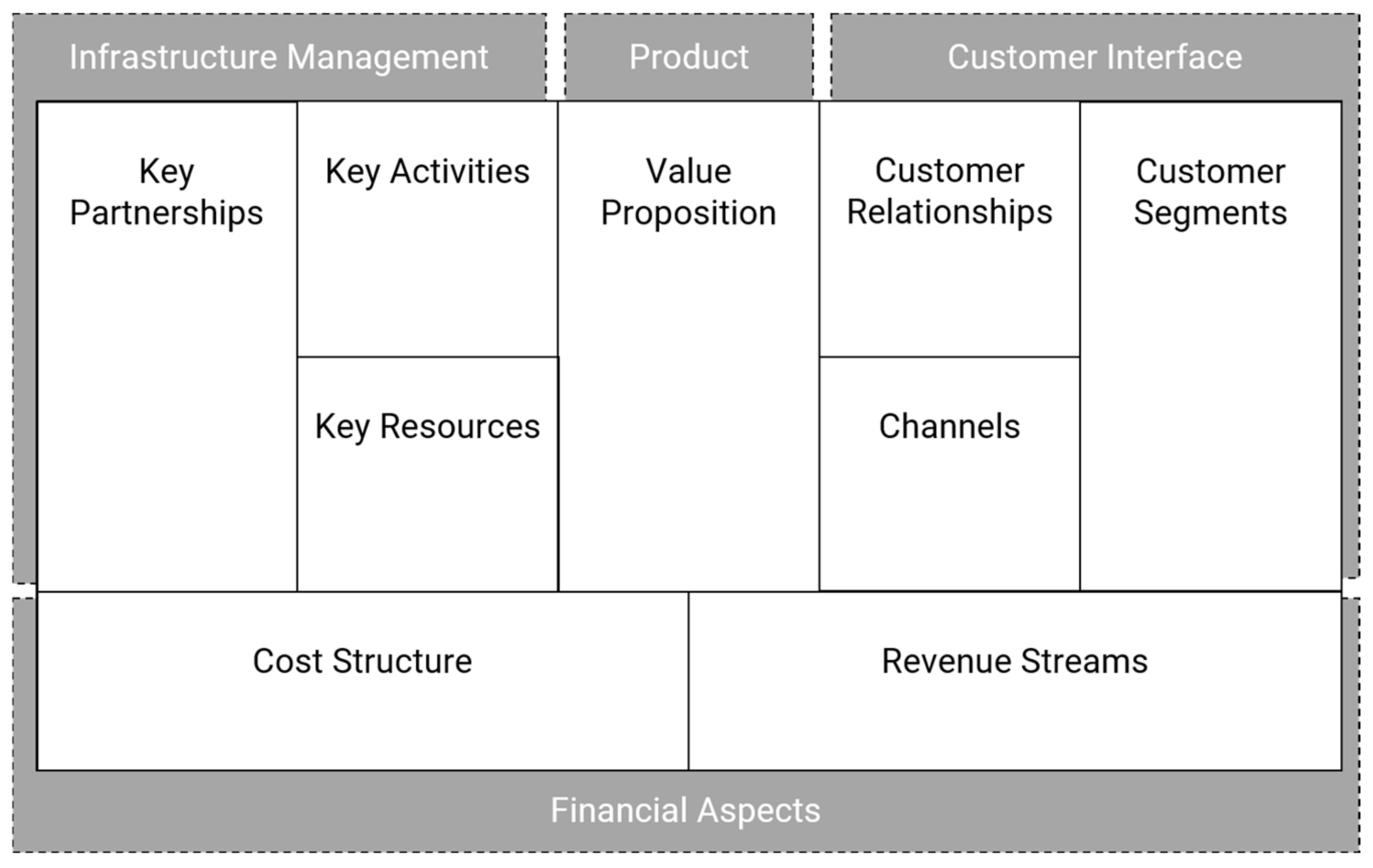

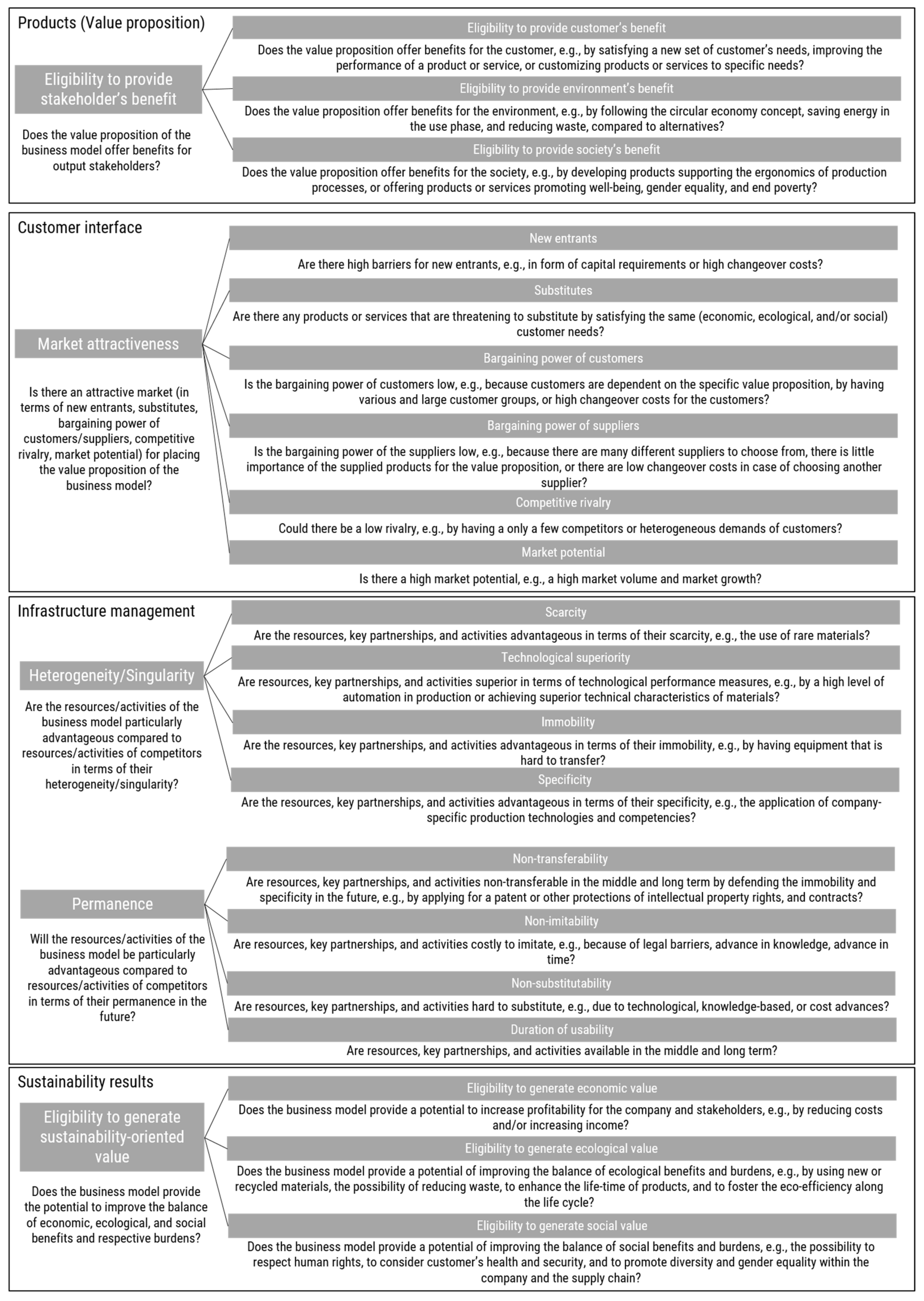

4.1. Resulting List of Criteria for Strategic Evaluation of Business Models

- The eligibility to provide customers benefits is reflected by the value proposition;

- Market attractiveness refers to the customer interface elements (customer relationships, channels and customer segments);

- The heterogeneity and the permanence of resources are the results of the infrastructure management (and its elements key partners, key activities and key resources);

- The eligibility to generate profit is considered by financial aspects (cost structure, revenue streams).

4.2. Resulting List of Sustainability-Related Criteria for Strategic Evaluation of Business Models

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bocken, N.M.P.; Rana, P.; Short, S.W. Value Mapping for Sustainable Business Thinking. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 2015, 32, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chesbrough, H.; Rosenbloom, R.S. The Role of the Business Model in Capturing Value from Innovation: Evidence from Xerox Corporation’s Technology Spin-off Companies. Ind. Corp. Chang. 2002, 11, 529–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sosna, M.; Trevinyo-Rodríguez, R.N.; Velamuri, S.R. Business Model Innovation through Trial-and-Error Learning. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 383–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schallmo, D.R.A. Geschäftsmodelle Erfolgreich Entwickeln Und Implementieren, 2nd ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; ISBN 9783662576045. [Google Scholar]

- Rehme, M.; Lindner, R.; Götze, U. Perspektiven Für Geschäftsmodelle Der Fahrstrombereitstellung. In Entscheidungen beim Übergang in die Elektromobilität—Technische und Betriebswirtschaftliche Aspekte; Proff, H., Ed.; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2015; pp. 409–428. [Google Scholar]

- Cardeal, G.; Höse, K.; Ribeiro, I.; Götze, U. Sustainable Business Models–Canvas for Sustainability, Evaluation Method, and Their Application to Additive Manufacturing in Aircraft Maintenance. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüdeke-Freund, F.; Freudenreich, B.; Saviuc, I.; Schaltegger, S.; Stock, M. Sustainability-Oriented Business Model Assessment—A Conceptual Foundation. In Analytics, Innovation, and Excellence-Driven Enterprise Sustainability; Carayannis, E.G., Sindakis, S., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan US: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 45, pp. 169–206. ISBN 9781137393012. [Google Scholar]

- Amit, R.; Zott, C. Value Creation in E-Business. Strateg. Manag. J. 2001, 22, 493–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schallmo, D.R.A. Geschäftsmodell-Innovation: Grundlagen, Bestehende Ansätze, Methodisches Vorgehen und B2B-Geschäftsmodelle; Springer Gabler: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2013; ISBN 9783658002442. [Google Scholar]

- Timmers, P. Business Models for Electronic Markets. Electron. Mark. 1998, 8, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afuah, A.; Tucci, C.L. Internet Business Models and Strategies: Text and Cases, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill Higher Education: New York, NY, USA, 2002; ISBN 0072511664. [Google Scholar]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Vladimirova, D.; Evans, S. Sustainable Business Model Innovation: A Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 198, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Business Models, Business Strategy and Innovation. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 172–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y. Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers and Challengers; John Wiley and Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Osterwalder, A. The Business Model Ontology—A Proposition in a Design Science Approach; Universite de Lausanne: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2004; ISBN 0071392319. [Google Scholar]

- Wirtz, B.W. Business Model Management, 2nd ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; ISBN 9783030480165. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E. Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2008; ISBN 9781416595847. [Google Scholar]

- Tesch, J.F.; Brillinger, A.-S. The Evaluation Aspect of Digital Business Model Innovation. In Proceedings of the 25th European Conference on Information Systems, Guimares, Portugal, 5–10 June 2017; pp. 2250–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, U. Umweltmanagement. Erfahrungen Und Instrumente Einer Umweltorientierten Unternehmensstrategie, 2nd ed.; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Reinhardt, R.; Christodoulou, I.; Gassó-Domingo, S.; Amante García, B. Towards Sustainable Business Models for Electric Vehicle Battery Second Use: A Critical Review. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 245, 432–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S.; Hansen, E.G.; Lüdeke-Freund, F. Business Models for Sustainability: Origins, Present Research, and Future Avenues. Organ. Environ. 2016, 29, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.; Short, S.; Rana, P.; Evans, S. A Value Mapping Tool for Sustainable Business Modelling. Corp. Gov. 2013, 13, 482–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Morioka, S.N.; de Carvalho, M.M.; Evans, S. Business Models and Supply Chains for the Circular Economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 190, 712–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.M.P.; Short, S.W.; Rana, P.; Evans, S. A Literature and Practice Review to Develop Sustainable Business Model Archetypes. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Kleef, H.; Ropes, D. Waste Management Firms as Catalysts for Developing SME’s Circular Business Models: The Possibilities of Industrial Symbiosis. Int. J. Innov. Econ. Dev. 2021, 7, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boons, F.; Lüdeke-Freund, F. Business Models for Sustainable Innovation: State-of-the-Art and Steps towards a Research Agenda. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 45, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoormann, T.; Behrens, D.; Kolek, E.; Knackstedt, R. Sustainability in Business Models—A Literature-Review-Based Design-Science-Oriented Research Agenda. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS) 2016, Istanbul, Türkiye, 12–15 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Joyce, A.; Paquin, R.L. The Triple Layered Business Model Canvas: A Tool to Design More Sustainable Business Models. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 1474–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upward, A. Towards an Ontology and Canvas for Strongly Sustainable Business Models: A Systemic Design Science Exploration; Graduate Program in Environmental Studies York University: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tewes, S.; Tewes, C.; Jäger, C. The 9×9 of Future Business Models. Int. J. Innov. Econ. Dev. 2018, 4, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.M.P.; de Pauw, I.; Bakker, C.; van der Grinten, B. Product Design and Business Model Strategies for a Circular Economy. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 2016, 33, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Götze, U.; Peças, P.; Richter, F. Design for Eco-Efficiency—A System of Indicators and Their Application to the Case of Moulds for Injection Moulding. Procedia Manuf. 2019, 33, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Götze, U.; Rehme, M. Bewertung Innovativer Geschäftsmodelle Bei Sich Wandelnden Wertschöpfungsstrukturen—Analyse-, Prognose-Und Gestaltungsrahmen Sowie Die Anwendung Auf Die Ladeinfrastruktur Für Elektrofahrzeuge. In Zeitschrift für Die Gesamte Wertschöpfungskette Automobilwirtschaft (ZfAW) Heft 4; FAW-Verlag: Bamber, Germany, 2013; pp. 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Hauschild, M.; Rosenbaum, R.K.; Olsen, S.I. Life Cycle Assessment Theory and Practice; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; ISBN 9783319859200. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, B.S.; de Simone Morais, J.; Teodoro, P.F. Life Cycle Assessment of Innovative Circular Business Models for Modern Cloth Diapers. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 249, 119364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP Setac Life Cycle Initiative. Guidelines for Social Life Cycle Assessment of Products; United Nations Publications: Paris, France, 2009; ISBN 9789280730210. [Google Scholar]

- Götze, U.; Schildt, M.; Mikus, B. Methodology for Manufacturing Sustainability Evaluation of Human-Robot Collaborations. Int. J. Sustain. Manuf. 2020, 4, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoormann, T.; Kaufhold, A.; Behrens, D.; Knackstedt, R. Towards a Typology of Approaches for Sustainability-Oriented Business Model Evaluation. Lect. Notes Bus. Inf. Process. 2018, 320, 58–70. [Google Scholar]

- Süß, A.; Höse, K.; Götze, U. Sustainability-Oriented Business Model Evaluation—A Literature Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2008; ISBN 9781416590354. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, J.B. Gaining and Sustaining Competitive Advantage, 4th ed.; Pearson Education Ltd.: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mikus, B.; Götze, U. Zur Bewertung Der Strategischen Bedeutung von Unternehmensressourcen—Instrumentenüberblick Und Vorgehensmodell. Z. Plan. Unternehm. 2004, 3, 325–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, B.W. B2B Digital Business Models; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; ISBN 9783030130046. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, R.M. Contemporary Strategy Analysis, 7th ed.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2010; ISBN 9780470747100. [Google Scholar]

- Wernerfelt, B. A Resource-Based View of the Firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 1984, 5, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikus, B. Strategisches Logistikmanagement; Deutscher Universitätsverlag: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2003; ISBN 9783824491285. [Google Scholar]

- GRI-Standards; Global Reporting Initiative: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016.

- Götze, U.; Northcott, D.; Schuster, P. Investment Appraisal—Methods and Models, 2nd ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; ISBN 9783642334368. [Google Scholar]

- Reichel, T.; Rünger, G.; Meynerts, L.; Götze, U. Environment-Oriented Multi-Criteria Decision Support for the Assessment of Manufacturing Process Chains. In Energetisch-Wirtschaftliche Bilanzierung—Diskussion der Ergebnisse des Spitzentechnologieclusters eniPROD: 3. Methodenband der Querschnittsarbeitsgruppe “Energetisch-wirtschaftliche Bilanzierung” des Spitzentechnologieclusters eniPROD; Neugebauer, R., Götze, U., Drossel, W.-G., Eds.; Verlag Wissenschaftliche Scripten: Auerbach, Germany, 2014; pp. 85–92. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, I.; Peças, P.; Silva, A.; Henriques, E. Life Cycle Engineering Methodology Applied to Material Selection, a Fender Case Study. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1887–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Höse, K.; Süß, A.; Götze, U. Sustainability-Related Strategic Evaluation of Business Models. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7285. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127285

Höse K, Süß A, Götze U. Sustainability-Related Strategic Evaluation of Business Models. Sustainability. 2022; 14(12):7285. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127285

Chicago/Turabian StyleHöse, Kristina, Anika Süß, and Uwe Götze. 2022. "Sustainability-Related Strategic Evaluation of Business Models" Sustainability 14, no. 12: 7285. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127285

APA StyleHöse, K., Süß, A., & Götze, U. (2022). Sustainability-Related Strategic Evaluation of Business Models. Sustainability, 14(12), 7285. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127285