Aethina tumida, commonly known as the small hive beetle (SHB), is a scavenger and parasite of social bee colonies native to South Africa, where it is considered a minor pest [

1]. In 1996, the SHB was first found outside its endemic range in the United States. Since then, it has spread rapidly and has been recorded in Egypt (2000), Australia (2001), Canada (2002), Portugal (2004, eradicated since), Jamaica (2005), Mexico (2007), Hawaii (2010), Cuba (2012), El Salvador (2013), Nicaragua (2014), Italy and Brazil (2014), the Philippines (2015), Belize, Canada and South Korea (2017), Mauritius (2018), Colombia (2020), and China (2017) [

1,

2,

3]. Europe is free of SHBs except in the Italian region of Calabria. SHBs were previously found in the neighboring region of Sicily, but are no longer present there. Due to the potential for significant damage to bee colonies and honey production in these new regions [

4,

5], the SHB is often considered a major pest outside its native range. For instance, Neumann and Elzen [

1] stated that:

Unlike the mite

Varroa destructor, the SHB does not directly attack adult bees, but feeds and reproduces in the combs of hives. In large and healthy colonies, the bees can often control small populations of SHBs and limit their reproduction [

6,

7]. Damages to beehives are caused mainly by sudden mass aggregation and the subsequent reproduction of SHBs, but the mechanism is not yet fully understood [

5]. In addition to possible colony loss, an important component of economic damage to beekeepers is honey and wax destruction that can occur with moderate SHB infestations [

8].

Economic damages caused by SHB infestations are not well documented. This is due to limited knowledge about the biological and ecological processes of SHB invasion in new regions, and the fact that beekeeping is a small industry in many world regions. The assessment of SHB invasions’ impacts on beekeeping industries is generally hampered by the lack of statistical information about bee-breeding production costs, revenues, and other economic data. This also means that SHB prevention and control policies have not been evaluated in economic terms or through cost-benefit analysis.

1.1. Cost Estimates of SHB Infestation and Eradication

The first published estimates of the economic damages of the SHB are those resulting from the early stages of the invasion of the United States. An estimated 20,000 bee colonies were destroyed in the initial SHB spread in Florida, causing losses of more than 3 million USD (2.4 million EUR) [

9]. The costs of invasion in some regions of Australia have also been documented. Rhodes and McCorkell [

10] provided a detailed assessment of SHB damages based on firm-level surveys in Australia, and recorded the loss of 4631 hives in 117 operations among 312 beekeepers surveyed. The average loss of bee inventory was estimated at 3300 AUD (1980 EUR) per operation or 84 AUD (50 EUR) per hive, with another 3400 AUD (2040 EUR) per operation for destroyed hive products and materials. To manage the invasion, the increased cost of production—increased travel to apiaries, purchase of chemicals, and other management costs—was estimated at 3800 AUD (2280 EUR) per operation and 140 additional hours per operation.

A survey conducted by Mulherin [

11] in Queensland estimated a cost per hive of 400 AUD (240 EUR), including clean up, control, and restoration. A survey of 1302 beekeepers conducted by Biosecurity Queensland in November 2010 estimated a loss of 3 million AUD (1.8 million EUR), with a complete loss of 12 to 15% of hives [

12]. According to a survey conducted between 2008 and 2016, the annual hive losses peaked at 5.5 million AUD (3.3 million EUR) during the 2010–2011 summer, decreasing to 1 million AUD (0.6 million EUR) in 2015–2016 as a result of both the steady uptake of various methods of SHB control and the unusually dry spring before the 2015–2016 summer [

13].

In addition to direct bee inventory loss and hive or equipment damages caused by SHB infestation, beekeepers may further incur economic losses from regulatory measures undertaken to eradicate or control SHB spread. For instance, beekeepers may see decreased ability to migrate, or trade reduced due to restrictions on the movement of bees, hive products, and beekeeping equipment (e.g., quarantines or export bans). In Australia, SHBs did not initially cause significant problems in commercial beekeeping operations, but restrictions halted the export of live bees and queens out of Australia, worth around 2 million USD (1.6 million EUR) per year [

14].

1.2. Policy Responses to SHB Invasions in the US, Australia, and Europe

Following the initial damages caused by the SHB invasion in the US, the species was given the status of major pest. The invasion also stimulated considerable research to understand the SHB better and help mitigate the economic impact on the beekeeping industry. However, no restrictions on hive movement or mandatory control and eradication practices were implemented. The SHB is no longer notifiable in the US, even if it is still a notifiable pest according to the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE).

In Australia, SHBs were initially managed as a notifiable disease. To prevent the spread to uninfected states or territories, the interstate and overseas movement of honey, bees, apiary products, and beekeeping equipment from the infected regions were subject to strict quarantine conditions for entry, and importers had to apply for permits. The SHB has since been removed from the notifiable disease list. However, by law, everyone in Australia has a general biosecurity obligation to take reasonable and practical steps to minimize the risks associated with invasive plants and animals under their control.

After the detection of SHBs in Australia in 2002, advisory sheets, booklets, and extension articles were produced in many countries, including the United Kingdom [

15]. The SHB was often presented as a major threat to EU apiculture’s long-term sustainability and economic prosperity [

4,

16].

In 2003, the European Commission implemented additional measures to protect EU apiculture. The SHB was declared a notifiable pest throughout the community, and additional import controls were established to reduce the risk of further SHB introductions from third countries (Commission Decision 2003/881/EC, now Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2020/692 [

17]). In 2020, the EU counted around 615,000 beekeepers and 18.9 million beehives [

18]. The value of honey produced in the EU is estimated at about 140 million EUR [

19].

1.3. SHB Eradication Policy in Italy

In 2014, when the SHB was first detected in the Italian region of Calabria [

20], the EU mandated that Italy set up an SHB surveillance system and implement protective measures [

21]. Accordingly, the Italian Ministry of Health (MoH) developed and started to conduct an eradication strategy [

22].

The strategy developed since the first detection has several components: strict regulations of bee movements across national and regional borders, including the establishment of a protection zone covering all apiaries where the beetle has been detected, with a ban on the transport of any bees in and out such a zone; a surveillance system of sentinel apiaries and inspections of managed apiaries in the whole country; mandatory use of traps; the destruction of apiaries where a single infected colony is found, with indemnity payments to beekeepers for the destruction of honey bee colonies, equipment, and supers with honey to provide incentives for beekeepers to comply with reporting requirements in addition to the threat of fines, which can be harder to enforce.

In two years, around 6000 hives were destroyed, and 2 million EUR were paid to beekeepers by the Italian government as compensation [

23]. The total financial burden borne by the state and regional governments for the control strategy also includes monitoring and surveillance costs (e.g., veterinary inspections of managed and sentinel apiaries), research, and information campaigns. According to the current National Plan of Surveillance of

Aethina tumida (MoH 2020), around 4000 hives must be clinically inspected every year (including around 250 in Calabria), and around 1500 inspections of sentinel colonies occur yearly in Calabria and Sicily. Though a detailed cost accounting is not available, a rough estimate indicates that the cost of the inspection program alone is likely to exceed 100,000 EUR per year, including personnel salaries and travel costs.

The strategy launched by the MoH was effective in eradicating the SHB from Sicily. In 2017, after 2 years of surveillance without any positive case of SHBs since the initial outbreak, the EU Commission lifted all safeguard measures on Sicily while continuing surveillance. On 20 June 2019, an infested apiary was found in the province of Siracusa (Sicily region). The same control and surveillance measures previously applied were adopted. Based on the favorable epidemiological situation in February 2020, the Veterinary Service of the Sicily region ordered the withdrawal of the protection zone established in the outbreak area in Siracusa.

In Calabria, on the contrary, the protection zone (20 km around the infected apiaries) and the surveillance zone (5 to 10 km from the outer border of the protection zone) progressively expanded over time. Since 2017, the protection zone covers the entire Reggio Calabria and Vibo Valentia provinces [

24]. Though the effort to eradicate the SHB was not successful, the prompt adoption of movement restrictions prevented the spread of SHBs to other regions. The model developed by the European Food Safety Authority [

25] simulates that through the natural spread, it would take more than 200 years for the SHB to move across the 250 km from Calabria to Abruzzo (Central Italy). In contrast, the transportation of infested hives for migration or other management accelerates the speed of diffusion up to tenfold in model simulations. Cini, Santosuosso, and Papini [

26] also found evidence that the two mechanisms of spread have very different rates. This finding is consistent with the observation that the spread of SHBs along the entire East Coast of North America took no longer than three years due to hive migration [

1].

Zoning and other biosecurity measures are likely to have had significant economic impacts on the beekeeping industry in Calabria and other Italian regions, although no cost estimates have been published so far. The impact has likely been severe on the queen production industry, which generates between 9 and 17 million EUR in yearly revenues, with exports valued at around 2 million EUR in 2020. These figures are based on the Italian Queen Bee Farmers Association’s estimate of 600 to 700 thousand queen honeybees being produced in Italy every year, with a market price per queen ranging from 15 to 25 EUR [

27]. In addition, around 150,000 queens are exported yearly, according to personal communication with the MoH. The ban on exports from the restriction zone has resulted in the shutdown of queen operations in Calabria, and is likely to result in further losses in beekeeping operations in Italian regions free from SHBs. Additionally, the interruption of annual migration from Abruzzo and other regions outside Calabria to the nectar-rich citrus groves of the region has likely had a significant impact on beekeeping activity.

Over time, dissatisfaction with the MoH’s eradication measures has grown among beekeepers in Calabria [

28,

29]. Compliance with reporting obligations of SHB presence in apiaries has eroded drastically [

30]. The pattern is visible in the statistics reported by the veterinary institute responsible for tracking the invasion: the data available on the IZSVe website show that in 2014, 8 of the 32 affected beekeepers had spontaneously reported the presence of

A. tumida to the local veterinary services, whereas from 2015 onward, all occurrences were identified through official surveillance activities (clinical inspections in managed apiaries and sentinel hives, see [

31]). This erosion of compliance is consistent with findings from other studies of disease eradication campaigns, where the loss of stakeholder support grows as the duration and total cost of eradication efforts increase while effectiveness decreases [

32]. Other studies have shown that the willingness of livestock owners to report disease is influenced by the amount of financial compensation paid in case of culling [

33]. In this regard, beekeepers in the Calabria region complained about payment delays [

29] and that indemnities only cover asset replacement value (e.g., destroyed hives and bee colonies, supers with honey) without accounting for costs related to business interruption. This latter cost cannot be covered by the MoH, which only covers losses directly related to eradication and containment measures; however, they could be considered by other agencies such as the Ministry of Agriculture. Other non-financial factors causing low compliance with the reporting requirements are the fear of the negative consequences of disease notification [

32], the lack of trust in the efficacy of the eradication measures proposed by veterinary authorities [

34,

35], and the method of culling [

36]. The destruction of entire apiaries where a single infected colony is detected has been increasingly perceived by beekeepers in Calabria as excessive and ineffective because the beetles may fly off the hive during the inspections, and can survive outside hives [

28,

37]. Low self-reporting increases the cost of monitoring SHB prevalence significantly, and is likely to limit the performance of any SHB management policy, eradication or other.

In September 2019, a new regulation was issued by the MoH that permits regional veterinary authorities in the protection zone to enforce the selective destruction of infected hives in the protection zones (where SHB is known to be established) only, provided a scientific opinion of the National Reference Laboratory is given for honeybee health. However, the mandatory destruction of a whole apiary when the SHB is found is maintained in surveillance zones or an SHB-free region [

38]. This selective destruction is yet to be implemented due in part to the lack of appropriate regional regulation.

1.4. Documenting Experts’ Opinions on Eradication and Control Policy

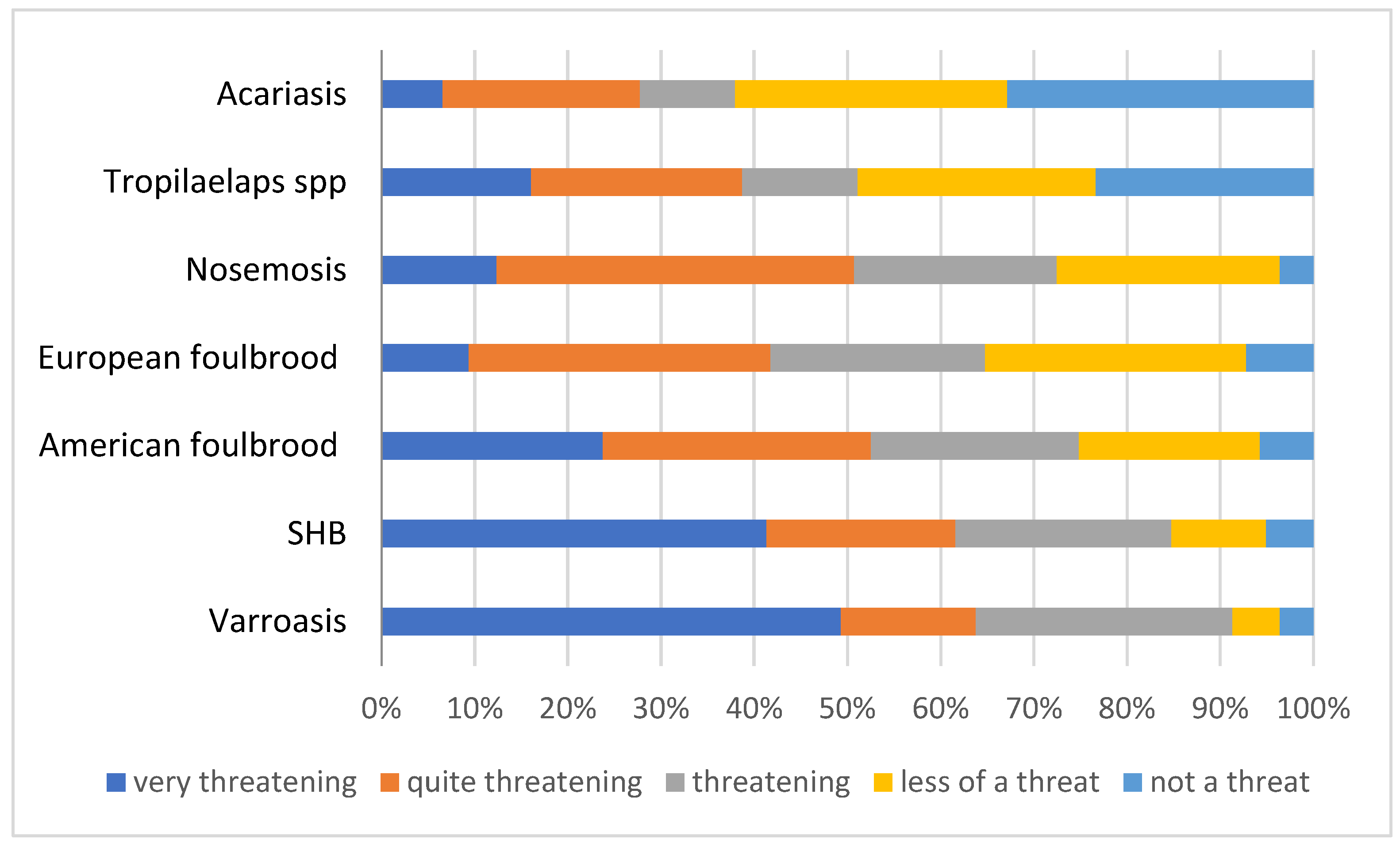

In order to assess the barriers to the adoption of biosecurity measures, we present the results of a survey on the perception of the effectiveness of SHB management in Southern Italy among bee experts, such as extension agents, veterinarians, and researchers.

We test whether extension agents perceive SHB invasion and the damages it causes differently from the broader scientific and veterinary communities. Differences in perception may emerge when the biological and epidemiological characteristics of the pest in the specific local environment are poorly understood, as may be the case with the SHB invasion in Italy. The direct observation of SHB infestation in the field, and interactions with beekeepers in the invaded regions may lead extension agents to develop perceptions and local subjective beliefs regarding the likelihood and magnitude of damages from the SHB invasion. These may differ from the evidence derived from past invasions in other locations, or from an assessment based on general scientific knowledge.

Our interest in the difference of stakeholders’ opinions towards the effectiveness of SHB management is motivated by the important role played by the collaboration between beekeepers and veterinarians in the control of exotic invasive species. The resolution of disagreements between stakeholders is crucial to ensure the participation of beekeepers in the surveillance and control efforts and, hence, the success of the SHB management policy.