Abstract

While there is a growing general awareness of sustainable development challenges among the students in Poland, the transition from a general notion to specific applications on various scales of designing the built environment is still a challenge. The described experience was aimed at setting up engaging learning experiences to improve education in sustainable urban design. In the presented case, introducing sustainability issues in urban design education was fostered by sharing international best practices and experiences through a Fulbright Specialist project, which allowed a range of means and opportunities to share knowledge and expertise in sustainable urban design. The Fulbright Specialist Program provides short-term consultancies of U.S. established professionals as experts on curriculum, faculty development, institutional planning, etc. In the discussed project, implemented in Poland, an American expert in real estate and sustainable urban development shared her experiences with an integrated sustainable approach to planning, development and design. The project demonstrated successful ways of maximizing the impact and knowledge-sharing in various activities: lectures, workshops, consultancies and TEDx talks. This experience shows how short-term workshops backed by a foreign specialist can trigger inspiration and opportunities for synergy in incorporating environmental, social and economic sustainability in education and campus design.

1. Introduction

While there is a growing general awareness of sustainable development requirements and challenges among architecture and urban design students in Poland (as in the whole society), it is necessary in the education process to concretize the general notion of sustainability and specific applications, opportunities and constraints on various scales of designing the built environment. Several teaching experiences have demonstrated that immersing students in a process similar to real professional challenges and providing a structured way towards finding valuable solutions resulted in increased engagement in students’ work, as compared with ordinary classes. Secondly, applying the knowledge to a situation that students experience first-hand and can well refer to provides better conditions for understanding and applying the knowledge. Initiatives providing an interesting and engaging learning experience can significantly enhance students’ overall engagement and academic success [1]. Thirdly, architecture students seem to highly appreciate first-hand experiences from successful practitioners as a supplement to “ordinary classes”.

The described teaching and learning experience aimed to improve education in sustainability in urban design. Introducing sustainability issues in urban design education was fostered by the Fulbright Program—a renowned scholarship program designed to enable cooperation between Americans and the people of other countries [2]. the Fulbright Specialist Program is meant for highly experienced, well-established academics and professionals from the U.S. to engage in short-term consultancies at host institutions. They serve as experts and consultants on curriculum, faculty development, institutional planning, etc., at academic institutions for a period of two to six weeks. The program is meant as a mutually beneficial opportunity for the host institution to have an experienced partner jointly examine an issue on a short-term basis and for the Specialist to gain international experience without leaving their position for a long time [3].

There are several international education cooperation programs, several Project-Based Learning studios, and several opportunities to invite practitioners to share their professional experiences with students. However, the project at hand was set up to combine a particular combination of innovation and novelty elements that the authors believe makes it worth sharing within the debate on sustainable education approaches:

- Immersing students in a structured process of finding valuable solutions within the design workshop based on the Project-Based Learning method;

- Appling the knowledge to a space known and accessible to the students—their university campus;

- Providing insights and guidance by a successful practitioner—the Fulbright Specialist with extensive practical experiences in the issues at hand;

- Enhancing the overall learning experience through guest lectures and consultations, especially through the renowned and acclaimed TEDx format;

- Using the prestige of the Fulbright Program to promote international cooperation and establish partnerships with other institutions (City Council, Polish Society of Architects, University Authorities, Local Media).

1.1. The Fulbright Specialist Project

The described Fulbright Specialist Project was entitled Sustainable Urban Development—an integrated approach: from municipal policy, through master planning and public participation, to building development. Its purpose was to share sustainable urban development best practices from the United States of America (US) with Polish faculty members, students and professionals. The project was implemented at the Faculty of Architecture of the Silesian University of Technology in Gliwice—a leading institution of education and research in architecture and urban design in Poland, dealing with the current built-environment challenges in the country. It was assumed that sharing US experiences in shaping sustainable urban form and showing interrelations on various scales and levels of planning, design and development can provide valuable professional input for the university community.

The invited Fulbright Specialist, Anyeley Hallová, is a development professional with cross-disciplinary experience on various scales of shaping the built environment—from municipal policy, through large-scale urban master plans and facilitating public participation processes, to developing mixed-use sustainable developments and individual buildings. She gained profound experience from Portland, Oregon—the city referred to as one of the most sustainable cities in the United States. She holds a Master’s Degree in Landscape Architecture from Harvard University, a Master’s in City Planning from MIT and a BA in Environmental Systems Technology from Cornell University.

The specialist shared her unique experience with multidisciplinary education and project teams. It seems that in many institutions worldwide (including the United States and Poland), there is a detachment in the fields of architecture and design, environmental policy, social sciences, real estate development and business. The specialist made the case that in order to solve the problems of the future—mainly climate change, inequality and economic instability—there needs to be stronger interaction between these fields. More importantly, academic institutions should take the lead in introducing multidisciplinary collaboration among students in their study courses. This approach could better prepare students of the Silesian University of Technology to be the leaders of the future while providing them and the University with a competitive edge in the marketplace of other institutions and in the workforce. Possible outcomes could include improvements in the curriculum by introducing post-graduate multidisciplinary courses or workshops.

1.2. A System Approach to Sustainable Urban Development

Shaping sustainable built environments requires a holistic approach that not only considers the physical form of the city and the design of its buildings but also its environmental systems, water and energy resources allocation, transportation networks and its relationship with natural and working landscapes. It also requires a system-based approach that considers the interconnected and dependent aspects of the needs of its people (social), the short-term and long-term viability of its plans (economic) and the land and resources it depends on (environmental).

The most common definition of sustainable development was established by the highly influential report Our Common Future, World Commission on Environment and Development in 1987, commonly referred to as the Brundtland Report. The report defines sustainable development as Development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs [4]. The essence of sustainable development is the rational use of resources and maximizing the social, economic and environmental benefits from human activities. As most of those activities take place in cities, sustainable development has several implications for shaping the built environment [5]. The paradigm of sustainable urbanism [6] postulates a holistic approach in three scales: polycentric structure of regions, metropolia and cities; urban grid of districts and neighborhoods; and the micro-scale of an urban block and buildings providing active frontages for public space. This implies compact and multifunctional urban tissue, with local access to services, green spaces and amenities, where density and intensity rationalize sustainable mobility.

The three pillars of sustainability are: environment, society and economy. However, an early focus on sustainability turned toward environmental considerations at the expense of societal and economic factors. Terms such as “green” and “earth-friendly” are now seen as synonymous with sustainable development rather than a system-based approach that understands the interconnection and dependencies of one aspect on another and that true sustainability cannot occur unless all factors are sustainable. This integrated and balanced approach provides responses that are bearable, equitable and viable.

1.3. A Sustainable Campus

In recent years, many universities have attempted to institutionalize the concept of sustainable development by incorporating it into the curriculum, research agendas, infrastructure, administration and operations. Universities are expected to be at the forefront of knowledge creation and development, which includes the area of sustainability [7]. Campuses and their masterplans, due to the nature of institutions being a large microcosm within “a complex ecosystem called the city”, need to consider the needs of multiple stakeholders. These stakeholders include the university faculty, staff, students, city residents, employees, business owners, officials and, importantly, the natural environment that all of these depend on.

This makes a campus, most especially at its edges or interfaces with the city, the perfect backdrop and case study to apply a sustainability framework [8,9,10]. True sustainable system thinking is the best tool for generating more bearable, equitable and viable solutions to the challenges at this interface, thus realizing latent opportunities for all stakeholders.

Contemporary, multi-functional urban campuses not only serve the universities but can also serve the local community and, moreover, be used for other means, such as popular education, youth activities, science popularization, university of the third age, as well as general urban functions, such as retail, catering, entertainment, etc. Important aspects of an urban campus are the general features of good public space, such as comfort, activities, connectivity and active frontages of the surrounding buildings [11]. Campuses also have the potential to be at the forefront of inspiring, flexible environments. For example, the concept of the “Learning Landscape” envisions the future of universities as a network of attractive places, providing students with opportunities for activities in formal and informal learning places, as well as inspiring, multi-functional and flexible environments for interdisciplinary activities, where due to increased mobility and technological advancement, students may choose the place and manner of learning [12]. The Silesian University of Technology situated in downtown Gliwice is essential and plays a critical role in the revitalization and reactivation of the city. University buildings and public spaces of the campus can either support or alienate collaboration between stakeholders. Successful recommendations would be plans that further progress knowledge, advancement, and innovation in the society of the University and the City while pushing conventional thinking toward innovations in economic, social and environmental sustainability.

2. Materials and Methods

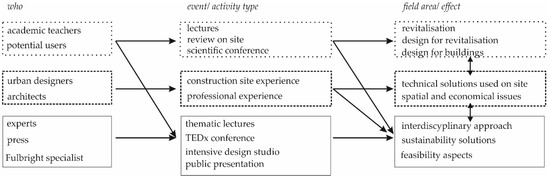

In order to take the best advantage of the specialist’s presence and experience and to achieve the best impact on the host institution, the project included a range of activities that aimed to trigger synergy and opportunities for collaboration and inspiration. The scope of work that the specialist engaged in included lectures for various audiences: students and staff, the Polish Society of Architects and TEDx participants. She also gave a keynote speech at the interdisciplinary Conference Region—City—Country, which links academics, administrators, politicians, planners and other parties interested in shaping urban space. She consulted with the instructors of the Silesian University of Technology, participated in and directed a workshop and developed educational materials. The individual PBL approach was organized as follows: special lectures were held in addition to ordinary lectures, and students also took part in the TEDx event and scientific conference. Additionally, a design studio was conducted in an unusual way as a very intensive two-week course instead of one semester. The most important input to the education program were specialists from outside of the university who attended the events. The diagram of the described teaching experience is shown on Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Diagram showing standard (dotted line), nonstandard elements (dashed performed by professionals) and additional (solid line) in the framework of the teaching method.

2.1. TEDxSilesian University of Technology: Interfaces

To popularize the specialists knowledge and enhance the profile of the workshop, a TEDx event was organized—TEDxSilesianUniversityofTechnology: Interfaces [13], with most of the the student participants in the organizing team (Figure 2). TEDx is a program of local, self-organized events that bring people together to share a TED-like experience and spark inspiration, deep discussion and connection, in the spirit of “ideas worth spreading”. The Polish–U.S. Fulbright Commission granted honorary patronage over the event. The specialist’s talk was entitled The City of the Future [14]. Other talks covered a range of transdisciplinary activities “at the interface” between design and other fields and were meant to give a fresh view of some of the issues that designers and engineers are dealing with directly or indirectly related to sustainability and design. Agnieszka Szóstek, a UX expert, discussed innovations in the user-centered campus design process. Kathryn Zazenski, a visual artist and Fulbright Visiting Scholar in Warsaw, demonstrated bonds between art and science. Peadar de Burca, an Irish writer, presented an outsider’s perspective on the urban quality of Gliwice, emphasizing the need for civic involvement. Daniel Bargieł, a developer, investigated the social influence on the decisions we make. Piotr Prokopowicz, a sociologist, demonstrated the importance of an evidence-based approach to life, science and design practice.

Figure 2.

The organizing team of TEDxSilesianUniversityofTechnology, including the students who took part in the described urban design.

2.2. Inspirational Lectures

Following lectures by the specialist provided a deeper insight into sustainability in the built environment. The presentation called Sustainability: Oregon Case Studies [15] reviewed the definition of sustainability in detail; gave a background on the State of Oregon and the City of Portland in comparison to Poland; and then reviewed four case studies, ranging in size from the region to the city, district and the project level: (1) Oregon Land Use System which uses land use policy, public participation and advocacy as tools of sustainable development; (2) SOUL District, which uses the tools of grassroots programming and real estate development; (3) EcoDistricts, which uses urban design and district energy systems; and (4) Framework, which uses renewable local materials, energy efficiency and economic development as its tools. The presentation included an evaluation of the environmental, social and economic benefits and challenges of each of the case studies. The presentation was a way to demonstrate how a sustainability framework can be taken to any project at any scale, be it regional planning or detailed building design. The finale of the presentation was a compelling argument for a multidisciplinary approach to both education and professional practice in order to solve the problems of the future and create plans that respond to the environmental challenges of the community, meet the needs of the people it serves and will be economically viable for years to come.

Another presentation was on the economic, environmental, and social goals of the award-winning project named Framework [16], which won a USD 1.5-million grant from the United States Department of Agriculture to design and build the first skyscraper made out of wood in the United States. The specialist described the design including the resilient design that has been designed to withstand a very strong earthquake; the design of the facade; sustainable best practices that reduce energy and water consumption; the users of the building; rural economic development goals; and the design considerations and benefits from using new engineered wood products as the structure of the building.

The specialist showed a range of her work. Showing her company’s housing development work, she discussed the motivation for each design and how they differentiated themselves from the marketplace by placed-based design that considers the user and a high level of environmental responsibility. While presenting examples of retail and office developments, the indoor/outdoor nature of the work was stressed as a pleasant and healthy place for people to work and shop and also as a market differentiator for creating value in the buildings and projects her company produces. The specialist also showed samples of her past work as an urban designer at EDAW, the largest landscape architecture firm in the world at that time. She focused on graphic representation as a tool for conveying an analysis of complex problems and how system diagrams can break down multi-level solutions for environmental and other systems responses.

2.3. Hands on Experience: Interfaces—Campus and the City Workshop

A key method of an architect’s education is immersing students in a process similar to real professional challenges and providing a structured way to find valuable solutions. The notion of PBL (Problem/Project-Based Learning) advocates teamwork, undertaking complex, realistic design challenges and providing opportunities to apply the knowledge—in our case, of sustainability—in urban design [17]. Gordon Lindsay [18] described three necessary elements of such a learning experience as: (1) Immersion—students are immersed in a project with a scope and complexity greater than the capacity of an individual student; (2) Exemplarity—the work and processes related to the project are a good example of what is found in their profession; and (3) Social contract—while being accountable for their own learning, students share responsibility in the team and learn from one another.

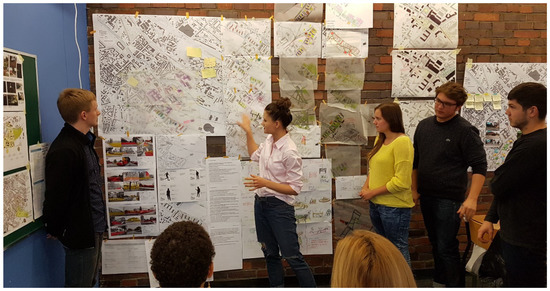

Such a process of a meaningful educational experience also relates to the psychological theory of flow [19], which describes the conditions for optimal experience and efficient activity. It argues that optimal effects come from performing realistic, tangible tasks that have well-defined goals, where feedback is available, and that give the possibility of using the possessed skills. Referring to urban design education, a good way of transmitting knowledge is a design studio and workshop methods, dealing with realistic issues important for students, increasing engagement and enthusiasm in their work (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

An interim presentation by one of the workshop teams.

The workshop aimed at combining the sustainable urban development insights with the case study of the Silesian University of Technology campus. It was organized within the Urban regeneration design studio for graduate students. The method of work entailed activities undertaken to identify the conditions and potential of the sites, i.e., research by design. Due to the revitalization nature of the elaboration, the method of work was equivalent to specific successive stages: diagnosis of the existing condition, delimitation of the area, urban evaluation, designation of the objectives, indication of the means and methods of revaluation and the revaluation project [20].

The campus for 20 thousand students is located in downtown Gliwice, a mid-size city with 180 thousand inhabitants, located within a 10 min walk from the main street, main square and railway station [21]. Like many centrally located campuses, it plays a critical role in the performance of the city [22]. University buildings and public spaces of the campus can either support or alienate collaboration between stakeholders. As Friedman observes: one single [campus] masterplan can transform a nondescript, slipshod building complex into an international cultural destination [23]. Successful recommendations would be plans that further progress knowledge, advancement and innovation in the society of the University and the city while pushing conventional thinking towards innovations in economic, social and environmental sustainability.

The aim of the workshop was to envision the improvement of functionality and sustainability of the campus area and the improvement of connections with the city (see Figure 4)—in other words, creating functional, spatial and ecological “interfaces” between the campus and the city. Students had the opportunity to apply the sustainability factors in their proposals. The integrated workshop exceeded the standard education method—separate work with specialized teachers: urban designers, planners and architects. The idea of the interfaces enabled an enhanced studio work in multidisciplinary teams with interdisciplinary approach and international perspective. The urban proposals would be later continued within the frame of an architecture studio.

Figure 4.

Overview map of the campus and students working sites: 1—Residential Campus/Dormitories; 2—Akademicka-Strzody Axis; 3—Chrobry Park; 4—Kłodnica River; 5—Connection to Old Town and Krakowski Square; 6—Southern Gateway to Campus.

2.4. Integrating Sustainability in Urban Design

In order to inspire and guide the students’ teams, a range of working questions were formulated to be addressed in the students’ proposals. The following environmental sustainability questions were asked regarding the environmental sustainability ideas: green building practices, green streets, increasing plant and animal biodiversity, alternative energy, indoor and outdoor air quality, stormwater management, water management, reduced reliance on cars, transit and bicycle transportation, renewable materials, environmental preservation, environmental remediation, divert waste from landfills, reduce greenhouse gas emissions and the use of recycled materials:

- What is the most pressing environmental issue in your community? Can your design help to solve this problem?

- Can your design reduce energy consumption or provide renewable energy?

- Can your design control stormwater or wastewater by reducing or reusing water?

- Can the design of your building provide a system for water or energy reuse?

- Can your design reduce impervious surfaces compared to a typical design?

- Can you use renewable materials in your design?

- Is your design respectful of environmentally sensitive areas?

- What are the environmental goals for the future development of your project?

The following social sustainability questions were asked to keep the following social sustainability ideas: 24 h community, mixed-uses, uses for underserved populations, the introduction of new land uses, community spaces, recreational areas, transportation hubs, food center, user-centered design and safety focused design:

- Who is your design made for? How did you identify this user group(s)?

- What do these groups want or need?

- How does your design meet the needs of this population you have identified?

- Is there an underserved group of people in this area? Can your design meet their needs also?

- What uses or amenities are missing in this community? Can your design provide these missing amenities?

- Are there community spaces lacking in this area? If so, can your design provide new community spaces?

- Will your design be well-used (24 h a day/seasonally) by the community?

- Is your design safe for pedestrians? Have you created places of unsafety?

- Will your design be embraced by the community in the long term? If so, why?

The following economic sustainability questions were asked to keep the following economic sustainability ideas: revenue-generating uses (housing, retail, hotel, office), private sector funding, Public–Private Partnerships (P3 or PPP), university expanding and growing, tourism dollars, co-working, business incubators, resilient design and the use of local materials that support the local economy:

- How does your project increase the economic viability of Gliwice or the University?

- Where are the materials in your design? Is there a way to utilize local materials or create goals for your project that utilize mainly local products?

- Who are the financial stakeholders in the success or the failure of your design?

- How can you leverage these stakeholders’ motivations to ensure the success of your project?

- Are there any economically disadvantaged groups? Is there an ability to have job training or opportunities for these groups as a part of your design?

- How will your design be maintained and funded over time?

- Is there an ability to design in a way that funds the future maintenance costs?

- Is there a way to design that reduces the future maintenance costs?

- Is there an ability to introduce private funding or uses into your project?

- Is there an ability to bring in a new source of revenue?

2.5. Literature

The intensive workshop was generally based on knowledge shared through lectures and experiences, but students were given a range of literature sources to be referenced on the topic of sustainability. Due to the practical issue of availability, the main sources were the freely available online materials prepared by Sendzimir Foundation—a leading Polish institution popularizing the applications of sustainable solutions in the built environment [24,25], as well as authors articles made available to the students [26,27].

3. Results

The students worked with the specialist during the intensive two-week workshop, concluding with a presentation, and continued their studio work through November 2016. In this regard, the specialist developed a “Sustainability Challenge”, asking the students to further develop their plans with a sustainability framework in mind. The recognition and prize money was offered to the top team—those who could demonstrate an understanding of and application of how to use a sustainability framework in urban design and architectural designs in the best way and how the plans and designs addressed environmental, social and economic sustainability. Among the six teams, the following four addressed the issues of sustainability in the most appropriate ways.

3.1. Improving the Sustainability of the Campus

The area of the dormitories is located in a strategic position, linking the sport and recreation part of Gliwice with the campus and downtown. The space between the dormitories is neglected, disordered, and mostly not functioning as a place for students. The group most adequately addressed the sustainability issues and, accordingly, was awarded the “Sustainability Challenge”.

The main idea of the project was to link the areas of the dormitories by the line of arranged greenery with recreation and service areas, giving a sense of security and providing various functions attracting active use not only for students but also for citizens of Gliwice (see Figure 5). Several short terms solutions were proposed: the main green path with recreation and services areas, joining students and city, the development of identification and identity of students with the place by, e.g., new facades of the dormitories, new ideas for internal courtyards along the green path—greenery arrangement, creating spaces for groups with different interests: outdoor gym, cinema, barbecue, parties, sculpture making, recreation area, etc.

Figure 5.

Perspective view of the existing dormitories (white) and design proposals for interventions using sustainable solutions; author: student group no 1; ref. background photography source: www.googlemaps.com (accessed: 1 November 2016).

Additionally, some long-term solutions were proposed: moving the planned road junction to the next street; limiting the traffic on the existing road and opening it up for people to connect students and separating a part of the dormitory area for young couples, PhD students, residents and guests; moving residents to another part of the city; changing and converting residential buildings to dormitories. Other proposals were: the creation of additional volume for services, change of ground floors for commercial services, creation of a multi-level car-park, closure of the area for vehicles, options such as: “kiss&ride”, “20-min luggage”. Furthermore, eco-solutions with new technologies were proposed, such as using renewable sources such as the sun, water and plants to create an ecologically friendly area with future constructions, infrastructure and the use of the underground system of waste disposal.

Environmental sustainability issues were mentioned, including reduced reliance on cars, transit, use of bicycle transportation, green buildings and streets, green walls, taking care of the existing and organizing new greenery areas, rainwater management, an artificial lake, volumes for collecting water for the greenery area, gardens, greywater for toilets (but how to do it?), the area slopes and the roof infrastructure should meet in collectors, use of recycled materials, palettes for the exhibition and seats, timber wood for new elements, etc.

The social sustainability issues were considered by mixed usage of spaces, such as new different services on the ground floors of the dormitories, and community spaces, such as new volumes for meetings, sports and work. The project relayed on recreation- and safety-focused design; it proposed several landscape architecture solutions for greenery, urban furniture and waste bin management. Additionally, economic sustainability was taken into account: cost-efficient changes, low rental prices in different business incubators, and opportunities for new work places and co-working with Gliwice incubators.

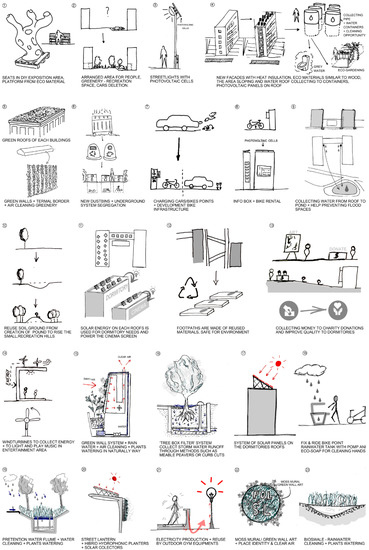

The Fulbright specialist assessed that this group proposed the best and deepest exploration of the sustainability issues and distributed eco-solutions through the site in a clever and reasonable way. While there were still some critical comments (some ideas could be picked and realized with better drawings rather than a light touch on all aspects; economic sustainability aspects could be pointed out in a better way), this group showed the best understanding of sustainability and the desired integration of various aspects of sustainability in the design concept. During the final presentation, the representatives of the university authorities commented that several of the ideas were valuable and could be considered in the planned redevelopment of the dormitories area. Circulation improvement proposals included speed limits, improving walkability and cycling, and reducing parking by providing a new car park on the edge of the site. Additionally, sustainability design proposals for every possible location have been proposed (see Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Sketches for sustainable solutions used in the design proposal by student team 1.

The Fulbright specialist endorsed the premise of short-term and long-term scenarios as a good way to look at the economic sustainability of the project. It would be better to test out the ideas in the short term before big investments are made, giving long-term options a greater opportunity for success and acceptance. However, the project could further explore environmental sustainability: eco-friendly ways of building a plaza by reusing water and power. The land is a crucial component of the built environment and can be planned, designed and developed to protect and enhance the benefits derived from a healthy functioning landscape.

3.2. Campus Park

The Park is a part of the campus. The group proposed a non-invasive project that would preserve as many existing trees and plants as possible. The authors suggested a commercial building with catering and recreational amenities, with environmental facilities such as green walls and a green roof. One of the design proposals was an auditorium to be used as an ice-skating rink in winter. The plan acknowledged the fact that Chrobry Park is occasionally flooded. The rainwater management system would use the subsidence of the auditorium, enabling the grass to hold water longer and enhancing natural filing through the soil to be absorbed by the plants.

The design included active and passive public spaces which could accommodate the interests of all social groups: jogging and walking paths, dog runs, seating areas, playgrounds, performance space, dining sites and an event area. The designed esplanade along the river banks was supposed to support the process of cleaning the Kłodnica River by filtering plants on the slope and the riverbed. Re-naturing the river and designing a public boulevard with seating expressed the effort to combine social and environmental goals.

While it is an interesting design concept, the issue was addressed mostly in terms of beautification than considering the park as a living system, fulfilling only the social needs. The idea of a large impervious amphitheater in the middle of the park is a radical intervention in such an environmentally sensitive idea. The proposal hardly addressed the maintenance and management of the park in the long run or the environmental factors (topography, natural flooding areas, animal habit, solar exposure). Thus, the design of the park should be grounded in its natural features and in the natural systems that have an impact over time. Additionally, the proposed riverbed planting was a solution not sufficient to secure cleaning the water in the river, as something more extensive must be carried out.

3.3. Kłodnica River Corridor

The Kłodnica River flows through Gliwice, linking two distant green areas in Gliwice: Chrobry Park on the campus and Chopin Park in the center. The group aimed to use the full potential of the river: activating the river corridor, opening the city to water and yielding social, environmental and economic profits (see Figure 7). The target was to make the waterfronts available by removing accessibility barriers and setting up places for integration. The landscaping ideas were: easing visual orientation in the area with different colors and signs for particular zones, increasing the prestige of representative places and creating walkways and educational places. The environmental aspects taken into account were: ensuring safe and high-quality water with natural ways of cleaning the water by using adequate plants on the waterfronts and in the current, different micro-habitats and water flow (declines, dilatation, narrowing); introducing new plants, as biological diversity helps to create attractive habitats for different types of animals; designing bike roads along the river; seating made of natural materials. The long-term targets were: to create flow-balancing reservoirs in Chrobry Park, which could save the city from floods; to eliminate noise by using water elements such as water curtains; plant passages for eliminating negative effects on the city environment (e.g., car traffic). Additionally, the economic aspects were discussed: improving the cooperation of the public sector with the private sector (the city, the Silesian University, private investors) and encouraging new development along the river such as trade and gastronomy points, hotels and entrepreneurship incubators.

Figure 7.

Sustainable ecological Kłodnica River corridor linking the campus and the center of Gliwice proposed by student team 4.

The attractive design missed giving greater attention to sustainability. The proposed impermeable, concrete paths do not respond in the best environmentally sustainable way. Instead, steel and wood were recommended as proper materials for the edge of the river. Other ideas, such as turning a straight bank of the river into islands of vegetation, were promising but not thoroughly developed.

3.4. Connection to the Old Town and Sustainable Mobility and Local Economy

While the old town is just 10 min walk away from the campus, the path is complicated, not legible and unpleasant due to two major crossings on the way. Despite the proximity, students often prefer to take a longer way along the main axis and the main streets. The aim was to make the shortest link comfortable and attractive. The proposals were: providing comfort for pedestrians (new crossings, wider lanes, green spaces along the way, signage, slowing down traffic) as well as a few infill buildings in key empty spaces, with active frontages on the ground floor. The second idea was to erect a new building at Krakowski Square, which could serve as the City Promotion Centre, hotel and student center. All the proposed buildings were designed as sustainable, with wooden recyclable structures and photovoltaic cells on the rooftop, reusing the rainwater, etc. Sustainability was articulated in the vision and project description, with a link between social and economic sustainability. The uses that meet the needs of the users also contribute to increasing the economic viability of the city and the university due to their proximity and placement within the city.

4. Conclusions: Fulbright Specialist Project Approach—Added Value, Synergies and Lessons for Sustainable Urban Design Education

The described teaching experiences have confirmed that expanding urban design education with new forms beyond traditional classes improves student engagement and results in better learning experiences [28,29,30], and experiential learning can also provide several benefits in communication sustainability issues in architectural education [31]. The term “sustainability” as a definition was understood by all students and seen as a desirable factor. However, there was little to no understanding of how to apply this thinking to urban design and architecture projects. The main request asked during these lectures by design professionals and faculty was the business case for sustainability, including metrics and data, to demonstrate to institutional partners, city officials and private sector clients the need for longer-term economic analysis and not just the first-in costs of a project. Additionally, they were interested in what economic tools were available to promote and pay for sustainable development. Given this, it is apparent that a system-based sustainability framework was not a part of the university curriculum and thereby not readily practiced in the private sector.

Based on the students’ presentation and response to the provided guiding questions on various aspects of sustainability, the students appeared to have a good understanding of how to plan for and evaluate their projects based on social sustainability. The majority of students did complete an analysis of the constituencies affected by their project, going so far as conducting on-the-street interviews to gain insight. Their diagrams showed a good understanding of both the 24 h nature of the city and the seasonal needs of the stakeholder populations. The topics of environmental sustainability, however, proved challenging, as students do not have a knowledge basis or exposure to sustainable planning or building practices. As far as economic sustainability, like in most design schools, they did not have a framework for starting to think about this topic. There was also a need to understand that sustainability can be applied to any scale—from a regional plan to the design of a single chair and in any industry—from the making of buildings to the production of food. A sustainability framework requires first believing in and making a commitment to the three aspects of sustainability; secondly, establishing goals or metrics of elevation; and then asking the right questions in order to creatively problem solve for these established goals. Fortunately, design school can be the perfect place for creative problem solving as it is cultivated and nurtured.

The discussed Fulbright Specialist project provided a range of ways to share insights on an integrated sustainable approach to planning, urban development and architectural design. The overall experience of the Fulbright Specialist project proved a successful impact on the Silesian University of Technology and triggered multiple synergic effects for collaboration and inspiration. The outcome increased the awareness of sustainable development in cities and buildings, enriching the design workshop and insights into upgrading the curriculum with an integrated approach to the sustainable development of the built environment.

By evaluating the project, potential recommendations for the improvement and concretization of sustainable urban design education within the Faculty of Architecture to move toward sustainability innovation in the environmental and economic sustainability were to (1) provide environmental sustainability training to the faculty; (2) have students research and present case studies on environmental sustainability solutions, so they can learn what tools and technologies are available to them; (3) create architecture and urban design studios whose entire focus is on how to apply environmental sustainable design practices; (4) create or encourage students to participate in multidisciplinary competitions; and (5) create multidisciplinary studios that include business students to increase awareness of economic sustainability issues. Since the discussed project, most of these issues were incorporated in both standard curriculum, blended learning activities [32], and occasional international and/or interdisciplinary projects, within the frameworks of Erasmus, ArchéA [33], Ceepus [34], programs, etc.

Several similar educational projects with international tutors further organized at the Faculty of Architecture certainly benefited from the experiences of the Fulbright Specialist visit in providing students and staff with several opportunities to use the specialist’s practical experience through lectures, consulting and workshops. The impact of the visit on the community was successfully enhanced by arranging her involvement in additional activities reaching beyond the university, such as the TEDx “Interfaces” event, which since then remained the brand of a guest lecture series for the faculty. Moreover, a framework for additional specialists’ participation in the SUT programs has been established. In most cases, such as an f.e. design study for a new pocket park in Gliwice [35], external companies were involved. Specialists from those usually delivered knowledge on sustainability that cannot be obtained by a traditional way of studying.

To conclude, as one of the key elements of sustainability is the reasonable and effective use of resources [36], the approach of maximizing the opportunities for knowledge sharing, collaboration and inspiration through an international cooperation program (efficient use of the program’s resources) could be recommended for other, similar intentional staff exchange programs to strengthen the efficiency and synergic impact of sustainable urban design education.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.H. and M.S.; methodology, A.H. and M.S.; investigation, T.B., A.H. and M.S.; resources, T.B. and A.H.; data curation, T.B. and M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, T.B., A.H. and M.S.; writing—review and editing, T.B. and M.S.; project administration, M.S.; funding acquisition, M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Polish-U.S. Fulbright Commission, Silesian University of Technology.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The project Sustainable Urban Development—an integrated approach. From municipal policy, through master planning and public participation, to building development was realized within the Fulbright Specialist Program (Project ID: 7019). TEDxSilesianUniversityofTechnology Interfaces was organized with the TED license. The event was granted patronage by the Rector of the Silesian University of Technology, Arkadiusz Mężyk, Dean of the Faculty of Architecture, Klaudiusz Fross, and by the Polish-U.S. Fulbright Commission. Speakers included: Anyeley Hallová, Aga Szóstek, Peadar de Burca, Kathryn Zazenski, Daniel Bargieł and Piotr Prokopowicz. Organizers: Michał Stangel, Magdalena Brzuska and a team of volunteers, students of the Silesian University of Technology. The workshop Interfaces Campus and the City included presentations by: Tomasz Bradecki, Krzysztof Gasidło, Grzegorz Nawrot, Ewa Twardoch, Tomasz Wagner, Dorota Winnicka-Jasłowska. Workshop tutors: Anyeley Hallová, Tomasz Bradecki, Michał Stangel, Andrzej Duda, Aleksandra Witeczek. Student groups: 1: Aleksandra Targiel, Magdalena Pawlus, Marcin Szlauer, Piotr Górny, Joanna Basek, Etienne Comi, Adrien Monnier. 2: Helena Szewiola, Bartłomiej Zdanowski, Anna Woźny, Jakub Skrok, Paulina Sikora. 3: Magda Rugor, Wojciech Zientek, Magdalena Malinowska, Anna Mirecka, Mafalda Conceigao, Carlos Villar. 4: Maciej Rogóż, Robert Bosiek, Magdalena Mazur, Zuzanna Kmak, Sonia Machej, Patryk Bryłka. 5: Zuzanna Procner, Anna Reklińska, Aleksandra Lesisz, Michał Wojarski. 6: Celestyna Kura, Piotr Synal, Anna Muras, Agata Sempruch.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Tarrant, M.; Schweinsberg, S.; Landon, A.; Wearing, S.L.; McDonald, M.; Rubin, D. Exploring Student Engagement in Sustainability Education and Study Abroad. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulbright, J.W. The First Fifteen Years of the Fulbright Program. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 1961, 335, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulbright Specialist Program Overview. Available online: www.worldlearning.org/what-we-do/Fulbright-specialist-program (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- World Commission on Environment and Development. Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Haas, T. Sustainable Urbanism and Beyond. Rethinking Cities for the Future; Rizzoli: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Farr, D. Sustainable Urbanism—Urban Design with Nature; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Too, L.; Bajracharya, B.; Khanjanasthiti, I. Developing a sustainable campus through community engagement: An empirical study. Archit. Res. 2013, 3, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulson, J.; Roberts, P.; Taylor, I. University Trends: Contemporary Campus Design; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Darren, R.; Kirrane, M.J.; Curley, B.; Brosnan, D.; Koch, S.; Bolger, P.; Dunphy, N.; McCarthy, M.; Poland, M.; Fogarty, Y.R.; et al. A Journey in Sustainable Development in an Urban Campus. In Integrative Approaches to Sustainable Development at University Level; Part of the series World Sustainability Series; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 599–613. [Google Scholar]

- Vaishar, A.; Koutny, J.; Zapletalova, J. Influence of higher education and science on physical structure of the city of Brno. ACEE Archit. Civ. Eng. Environ. 2009, 2, 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Gehl, J. Life between Buildings: Using Public Space; Arkitektens Forlag: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Winnicka-Jasłowska, D. New outlook on higher education facilities. Modifications of the assumptions for programming and designing university buildings and campuses under the influence of changing organizational and behavioral needs. ACEE Archit. Civ. Eng. Environ. 2012, 5, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- TEDxSilesianUniversityofTechnology. Available online: https://www.ted.com/tedx/events/20618 (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- Hallová, A. The City of the Future. Talk at TEDxSilesianUniversityofTechnology. 2016. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XSjfqSdqKsY (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Hallová, A. Sustainability: Oregon Case Studies; Polish Society of Architects in Katowice: Katowice, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hallová, A. Framework, Project Housing Development Work, Project^ Retail and Office Developments; Lectures in Architecture and Urban Design Classes: Gliwice, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Trigwell, K.; Reid, A. Introduction: Work-Based Learning and the Student’s Perspective. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 1998, 17, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcock, G.L.; Blyt, H. Defining, Profiling and Accommodating Learning Diversity in an International PBL-Environment. Available online: http://ale2009.ac.upc.edu/ (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience; Harper and Row: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Gasidło, K. Urban Regeneration and Revalorization Studio Curriculum and Lecture Series; Silesian University of Technology: Gliwice, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Campus of the Silesian University of Technology. Available online: https://www.polsl.pl/uczelnia/en/campus/ (accessed on 11 February 2022).

- Gliwice—Education and Science. Available online: https://gliwice.eu/en/city-gliwice/education-and-science (accessed on 11 February 2022).

- Friedman, D. Campus Design as Critical Practice. Places J. 2005, 17, 1. Available online: http://escholarship.org/uc/item/6tg4p87s (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- Kronenberg, J.; Bergier, T. (Eds.) Challenges of Sustainable Development in Poland, Sendzimir Foundation. 2010. Available online: https://systemssolutions.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Challenges_of_Sustainable_Development_in_Poland.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Sendzimir Foundation: Sustainable Development Applications Series, 2010–2018. Available online: https://sendzimir.org.pl/en/publications/sustainable-development-applications-series/ (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Bradecki, T.; Stangel, M. The Image of Density—Challenges of Delivering Compact Urban Structure in Contemporary Urban Design in Poland. ACEE Archit. Civ. Eng. Environ. 2011, 4, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Stangel, M. Shaping Contemporary Urban Areas in the Context of Sustainable Development; Gliwice University Press: Gliwice, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Stangel, M.; Szóstek, A. Empowering citizens through participatory design: A case study of Mstów, Poland. ACEE Archit. Civ. Eng. Environ. 2015, 8, 47–58. [Google Scholar]

- Bradecki, T.; Stangel, M. Freehand drawing for understanding and imagining urban space in design education. ACEE Archit. Civ. Eng. Environ. 2014, 7, 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Stangel, M.; Witeczek, A. Design thinking and role-playing in education on brownfields regeneration. Experiences from Polish-Czech cooperation. ACEE Archit. Civ. Eng. Environ. 2015, 12, 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Brzezicki, M.; Jasiolek, A. A Survey-Based Study of Students’ Expectations vs. Experience of Sustainability Issues in Architectural Education at Wroclaw University of Science and Technology, Poland. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stangel, M. Blended Training Activities in On-Line and On-Site Exploration of the Urban Structures, FAMagazine. Ricerche e Progetti Sull’architettura e la Città. 2021, pp. 176–185. Available online: https://www.famagazine.it/index.php/famagazine/article/view/839 (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Amistadi, L.; Balducci, V.; Bradecki, T.; Prandi, E.; Schröder, U. Mapping Urban Spaces: Designing the European City; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Adamiak, M.; Bartnicka, J.; Bradecki, T.; Górski, M.; Stępień, M.; Tobór-Osadnik, K. Experimental summer school—Lessons from Ceepus Summer School in Gliwice, Poland: Interdisciplinary approach in shaping sustainable public space. In Proceedings of the 12th International Technology, Education and Development Conference, INTED 2018, Valencia, Spain, 5–7 March 2018; Gomez Chova, L., Lopez Martinez, A., Candel Torres, I., Eds.; IATED Academy: Valencia, Spain, 2018; pp. 4331–4340. [Google Scholar]

- Bradecki, T.; Opania, S. Pocket Park in Gliwice. In Possibility Study for an Education Center for Social Responsibility, Environmental and Cultural Education; Silesian University of Technology: Gliwice, Poland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- OECD Policy Brief: Sustainable Development Strategies What Are They and How Can Development Co-Operation Agencies Support Them? 2001. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/dac/environment-development/1899857.pdf (accessed on 29 May 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).