1. Introduction

Cities continuously face challenges, points of depression, and illness. These issues influence human living and behavior. They can deteriorate if not treated with great care. One crucial area in cities is the historic urban area in the city center, given their architectural and social values, which is losing importance due to rapid urbanization [

1]. When building sustainable cities, rapid urban growth is one of the major issues that causes environmental problems, such as unregulated urban expansion and the degradation of ecological resources [

2]. It is essential to achieve a smart, sustainable solution by regenerating old towns that support the dysfunctionalities of urban deterioration, economic obsolescence, and social deficiency. In addition, the implementation of redevelopment strategies and programs for the regeneration of degraded urban spaces or the reuse of abandoned buildings and previously disused urban land [

3], help to increase the attractiveness of urban centers and the wellbeing of citizens [

4,

5,

6].

Urban regeneration started as urban reconstruction in 1950, then modified to urban revitalization in 1960, urban regeneration and redevelopment in 1980, and finally urban regeneration in 1990 [

6]. Urban regeneration aims to recover damaged urban areas by enhancing quality of life and preserving the urban character [

1]. It considers a range of scales, from buildings to blocks, and neighborhoods to cities [

7].

Lee believes that researchers are making a significant contribution to sustainable urban regeneration, urban regeneration, and urban design [

8]. Best practice models and general principles underpinning urban regeneration are fairly well known [

3] and emphasize that urban regeneration interventions should always be adapted to local governments’ urban development models and specific geographical contexts [

3,

9,

10]. In contrast, there are some studies of urban design where researchers have realized the benefits of sustainable urban regeneration and regeneration approaches. According to Tin and Lee [

11], urban regeneration can be accomplished efficiently by improving infrastructure conditions. Future designs of street layouts should be equipped with walkable street networks and bikeable street network infrastructure. Planning specific routes that are relevant to the local contexts significantly reduce traffic congestion, high population density, and they promote sustainable urban development [

12]. The development of accessible, safe, and functional urban green spaces for recreation fosters an environment for a livable city [

13].

Despite most of the published literature is about sustainable urban regeneration, some research gaps exist. As a result, detailed approaches for implementation—for instance, quantity or quality improvement—cannot be acquired from these studies. Furthermore, despite the relevance of urban regeneration and interventions in the development and design of sustainable cities, only a few contributions have quantitatively examined the actual sustainability outcomes of different urban regeneration interventions [

3,

10,

14,

15,

16]. Moreover, a lack of flexibility is observed in many studies on strategies for sustainable urban regeneration, where the approach is specific to a particular kind of development. For example, blighted neighborhoods are essential for the municipality to be regenerated strategically to prompt the city to achieve sustainable urban revitalization; therefore, urban regeneration and its implementation should be flexible and follow the local context.

The study examines how modern urban planning ideas are applicable within an area. It is crucial to incorporate integrated and systemic methods concerning urban development and regeneration that are likely to represent interactions among urban groups [

17]. The researchers examined Doha Old Ghanim, one of Qatar’s oldest neighborhoods, as an example of rapid development that ignored old districts and resulted in sprawl, leaving houses in poor condition and subjecting them to further change based on the new residents’ lifestyles, economic abilities, and requirements. Traditional buildings were harmed and even threatened by these changes. As Old Ghanim serves as a major transitional zone and a destination, the revitalization of this area will influence the city of Doha. A conceptual framework and strategies are proposed to renew blighted neighborhoods in Doha, in terms of a model that impacts the development of, and upgrades, the built setting.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Blighted Neighborhoods

A neighborhood is defined as the regional segment of a city, which maintains its characteristics and features [

18], and whose social causes result in physical variety [

19]. There were solid dynamic relationships between old urban textures and residential structures; however, this central element in urbanism has been lost due to sudden changes associated with urbanisation. The incapability to update land use and the lack of effective administration to adapt to modern world changes has disadvantaged communities in that they cannot sustain inflows of new people and activities [

20]. As a result, the detrition of the blighted area has spread [

21,

22]. In search of a practical solution, sustainable urban regeneration has been recommended worldwide.

2.2. Sustainable Neighborhood Regeneration

“Our Common Future” is a report published in 1987 by the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED), wherein the vital concepts approach of sustainable development was introduced [

23]. According to the report, sustainable development refers to “the development that satisfies the requirements of the current generation without compromising the future generation in meeting their own needs” [

22,

23,

24]. Sustainable neighborhood regeneration is a long-term strategic approach for improving and rehabilitating a blighted, urban, neighborhood [

25]. Building reconstruction, slum removal, physical regeneration, and other components are included in the regeneration approach [

26]. With the help of neighborhood regeneration, problems such as social coherence, physical deterioration, neighborhood crimes, and environmental pollution can be fixed. Among other benefits, it can enhance social networks, improve the building situation, revamp the living environment, and there are ultimate goals that ensure that the local communities are not reluctant to stay in the neighborhood [

6]. On this scale, neighborhood regeneration projects can improve the living conditions and adjust according to the precise needs of the residents. In addition, these projects can also follow a larger urban vision for the city [

27]. In this context, sustainable urban development is closely related to neighborhood regeneration projects [

28].

2.3. Blighted Neighborhood Regeneration: Sustainable Considerations

The increasing inflow of the workforce and residents in cities has created urban development challenges about appropriate land division and identification of land uses, thus changing the urban landscape to adapt to new demands [

29]. Urban identity is an essential factor affecting the implementation of the neighborhood regeneration strategy. The literature on the urban environment refers to diversity and continuity as crucial concepts in understanding urban development [

30]. Additionally, the city’s revitalization must consider environmental and cultural interplay in different sites and amenities [

31]. On top of that, a successful regeneration project should improve the life opportunities of the residents and promote social cohesion and a sense of belonging in areas dealing with several social issues, such as inequality, displacement, and poor quality of livability [

32]. According to Ryn and Calthorpe, urban planning and architecture play a significant role in passing culture to the next generation. The dynamics between and progression of, the artificial urban environment and the city’s social fabric can be mediated by the richness of its urban culture [

33].

The same rise in the workforce and residents can have a negative impact on the load of the urban network and can bring new challenges [

29]. One of the adverse effects is the influence on health conditions, primarily for low-income inhabitants, and the possibility of gentrification [

34]. In addition, the adjoining properties can have an unintentional negative impact due to urban regeneration, which tends to reduce their worth beyond the boundaries of this project [

35]. The likely negative consequences witnessed by urban regeneration programs are believed to be the loss of local characteristics, social segregation, and the relocation of residents [

36]. At the same time, cultural decline can be the product of a faulty interplay between progress in the city’s physical development and changes in its social structures [

33].

However, sustainability indicators are not standardized in cities around the world, although they help identify and monitor the progress of the environmental outcomes of urban development [

37]. Moreover, the inability to locate outstanding areas, means that local needs in the urban regeneration process cannot be fulfilled, due to the aftermath of general policies and strategies [

38]. Furthermore, neighborhoods with close geographical locations may adjust to the same regeneration strategy; therefore, the urban regeneration decision-making process must consider the abovementioned principles based on the local context and the development area.

3. Conceptual Framework

Several main urban dimensions, including social, economic, environmental, cultural, and physical aspects, are identified by [

39]. Given the approach and research shortcomings, this study develops a range of assessment policies based on the physical dimensions which arise from the case-study analyses and literature review.

Some researchers are concerned with the urban design process, recommending that old areas be acknowledged to increase the urban regeneration project’s sustainability. Central districts should be comprehensively re-imagined, including physical developments [

40]. The urban design’s physical expression is part of sustainable development. It is possible to identify design principles that help sustainable development [

41] and establish a sustainable urban design principles framework, as the concepts were extracted from the literature associated with urban design. Each of the tenets are linked to various sustainable design principles. Holden [

42] states that tenets and principles are interrelated, thus allowing a sustainable approach. The sustainability progress is monitored using relevant indicators of urban sustainability. Moreover, Wang creates a social sustainability framework with a three-level constitution [

43]. Each sub-theme presents the critical inclusions of social sustainability and where indicators need to be further developed.

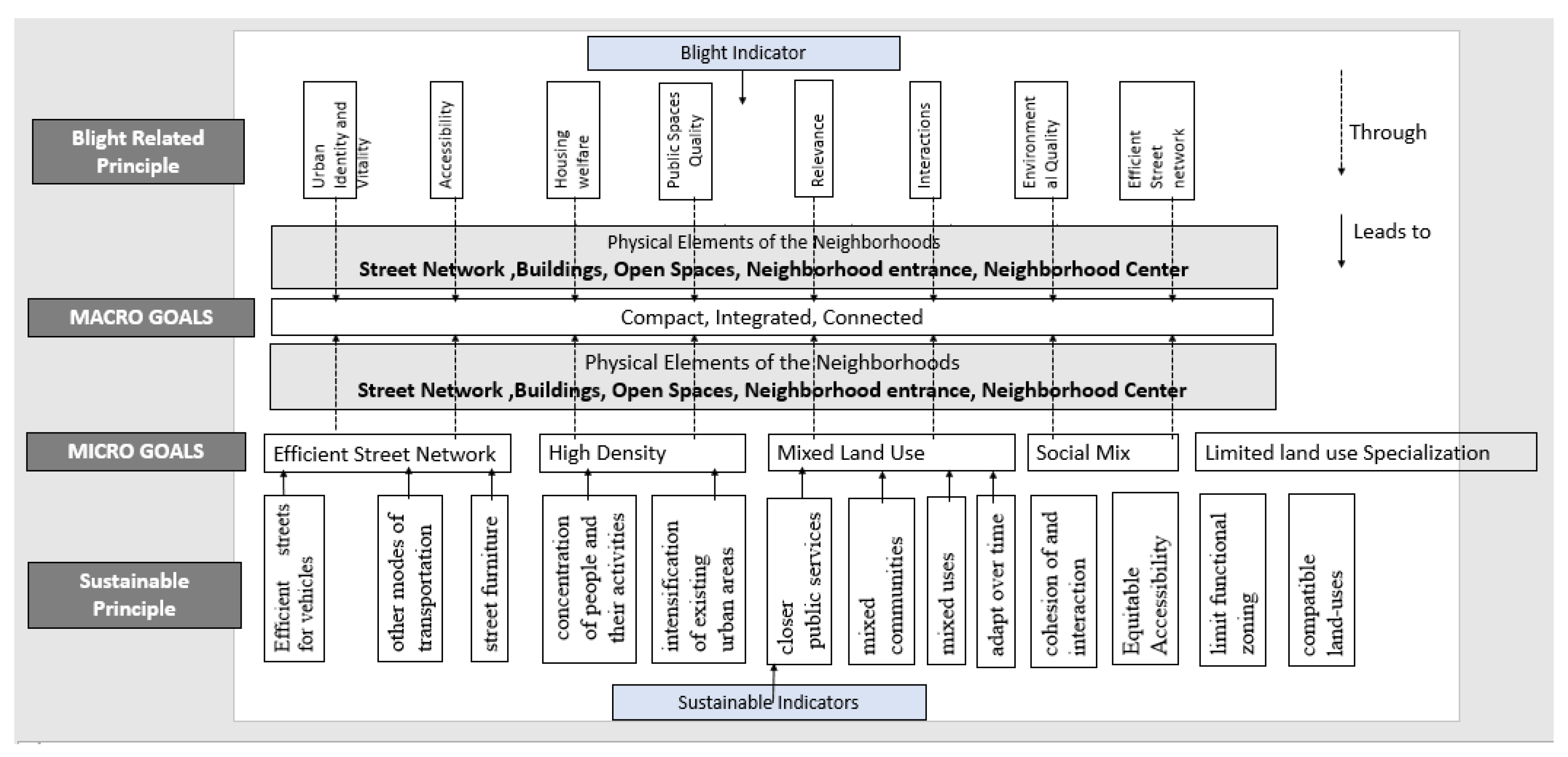

A framework for the regeneration of physical sustainability related to the blighted neighborhoods within Qatar has been extracted from Wang’s model in

Figure 1. Aspects of the framework include urban regeneration, and micro- and macro-objectives keeping sustainability development as indicators and principles for the urban development plan. The authors established a strategy for the urban regeneration project for Qatari blighted neighborhoods after analyzing the physical indicators of urban sustainability and its principles and goals. The framework has been established by integrating already available regeneration models. The focus was on the physical features of the established environment, which is relevant in terms of blight settings.

3.1. Identification of Macro and Micro Goals of Sustainable Urban Regeneration

Objectives indicate that the required future position is to resolve issues within the community. When the objectives are clear, the policies and action plans can be specified in more detail to allow the successful implementation to happen. Sustainable urban development can be achieved through four general goals: environmental enhancement and socio-cultural, economic, and physical aspects [

44]. The UN-Habitat lays out the three key features of sustainable cities and neighborhoods: “compact, integrated, and connected”. Five guiding principles support these, including: (i) adequate space for streets and an efficient street network, (ii) high density, (iii) mixed land-use, (iv) social mix, and (v) limited land-use specialization [

45,

46,

47].

3.2. Identification of Sustainable Blight Regeneration Principal

According to Habib [

48], there are five physical aspects of the urban design framework: street network, buildings, open spaces, neighborhood entrances, and neighborhood landmarks. Various urban design principles contribute to the sustainable urban redevelopment of these elements. Per their relevance to blighted conditions, several of them have been shortlisted in

Table 1. The principles may not be definitive yet, but they represent the essential typical design objectives and variables within the literature. Moreover, they emphasize benchmarks needed to achieve the required quality for the new regeneration. Furthermore, there is a requirement to present sustainable design positively regarding the blighted neighborhood.

3.3. Identification of Indicators of Sustainable Blight Regeneration

To identify indicators for sustainable regeneration, the authors refer to the EUROSTAT, the OECD, the World Bank, and the European Environment Agency. The current literature indicates that urban regeneration performance is measured through the analysis of neighborhood sustainability, where an indicator–draft list focuses on the neighborhood’s physical features. Initially, the search extracted several indicators for urban integration and interpretation. However, the authors reduced the list when considering the relativeness criteria regarding the blighted neighborhood’s issues, as presented in

Table 1.

3.4. Structure of Urban Regeneration Strategy

The established framework has been attained by developing criteria for urban regeneration to determine its quality. Its application helps achieve a comprehensive sustainability regeneration system within the built environment at a local planning level. It can be classified into three levels. The first level is a significant intervention that applies to most indicators. The second is a moderate intervention that applies to some aspects of the indicators. The third is minor intervention, such as painting, cleaning, and maintenance. The framework is integrated for urban regeneration as per the sustainability goals. The essential components are extracted using urban design principles and related indicators to upgrade the physical elements to attain micro and macro-objectives (

Figure 2).

4. Methodology

4.1. Research Approach

Determining urban planning and regeneration follows a set of objectives that guide the development. First, an investigation of the existing urban conditions within the area was executed to establish an evidence base for the design solutions and consider the proposed changes’ effectiveness after their implementation. Elements addressed explicitly in the proposed urban planning and design regeneration process relate to the connectivity enhancement, the social character of the place, urban form, amenities, quality of the urban environment, type of existing street fabric, transportation links, and existing buildings.

The urban design indicators and principles represent the vital components of the regeneration strategy. The following components have been extracted from the literature and were modified based on the goals of urban design and planning policies for blighted redevelopment. The proposed strategy should be assessed for reliability and validity; thus, the current appraisal framework is implemented as the blighted Qatari neighborhood is implemented within the case study. Hence, the case study procedure has been applied to the research. The required data was collected through internet research, academic databases, site visits, and observations. The collected data from the literature and real-life observations were analyzed according to their contribution to our research goals. As a recommended approach, applying the strategies is based on theoretical and analytical studies.

4.2. Data Collection Tools

Site analysis and studying the neighbourhood’s physical elements were used to gather the data. These data collection tools were created using a well-established definition of sustainable neighbourhood redevelopment, including qualitative and quantitative assessments. Investigation of the site and observation of the local location of the Fareej Old Ghanim district provided the qualitative data for the research. The researchers created site analysis maps to understand better the built environment’s current state, including land use, building heights, site orientation, transit alternatives, road networks, walking distances, and connectedness to the surrounding communities. In addition, daytime observations were conducted for the detailed documentation of the physical environment and to reduce the negligence in the perceptual state of the urban environment. Photographs of the neighborhood’s four critical physical elements were taken to obtain a visual analysis of the study area. These approaches collected important physical, cognitive, and geographical data to meet the research objectives. They discovered several site opportunities, as well as obstacles, because of these evaluations.

5. Case Study

Doha, the capital of Qatar, rapidly encountered growing urbanism amid the growth of its economy [

54]. Qatar’s economic prosperity was due to the discovery of natural gas and oil resources in 1939, which created unlimited trade opportunities for Qatar, especially in 1949, when petroleum was first produced [

55]. In addition, the country is recognized as a fast-developing region with a distinctive demographic profile, with an uppermost man to woman ratio, and it has the second-highest number of overseas residents globally [

56]. The Old Al Ghanim neighborhood is a part of Doha’s historic downtown. According to Fletcher and Carter, Old Ghanim is the oldest part of Doha, with significantly better water quality and proximity to the sea and mosque access [

57]. Compared with the rest of the districts, it also had better access to the Souq. Rapid economic development within the region led to the drastic urban sprawl and the Ghanim family’s relocation. These houses were taken over by foreign workers hired by the local companies, who naturally adapted the neighborhood based on their lifestyle, economic abilities, and requirements. The neighborhood has been challenged due to its degradation, street activation, and public realm.

5.1. Site Analysis

5.1.1. Location Map and Connectivity

Al Ghanim consists of three zones (16, 17, 18). It is located in the heart of the old Doha city centre, surrounded by similar areas that share the same building fabric and development challenges. Zone 16 is located in line with the new port and with the sea shoreline from the north side, which, at the same time, is connected by a straight road starting from Corniche Street vertically, which penetrates the zone by dividing it into two subzones. Another primary separation of the zone is caused by the main highway (Ras Abu Abood) running horizontally through the top end of the area, separating it from its Ghanim zones with two parallel roads, which separate it further into four distinct sub-zones. The highway itself enforces high accessibility and connectivity of the zone through penetration with an eight-lane wide road that reaches the new airport (

Figure 3).

5.1.2. Transportation

The current road system of Old Ghanim is designed so that the three main roads of AL Matar Street, Ring Road, and Ras Abu Abud Expressway allow the public to enter the neighborhood. It is evident from the images that most of the vehicles on the roads are cars which leads to heavy traffic congestion, specifically at peak times. Even when the traffic flow is smooth on the three main roads, the streets that are linked face enormous traffic jams because of their narrow design, as shown in

Figure 4.

The Karwa bus service has two stops within a 10 min walk radius. The Doha Al Jadeeda Metro is the closest station to Old Ghanim within a 550 m radius of the neighborhood centre. The physical texture of Fareej Old Ghanim lacks cycling lanes, which are not considered a mode of transportation. Moreover, there is a dearth of sufficient parking areas and public transportation facilities in the neighbourhood; however, the entire neighborhood has a 10 min walking distance between its furthest parts (

Figure 5).

5.1.3. Existing Land Use

A mixed-use urban development style characterizes the neighbourhood of Old Ghanim. Single-family and multiple-family residential units fulfil the needs of citizens. Commercial activities, offices, markets, and hotels are located predominantly on the periphery of the building blocks. The public service offices, such as the Qatar Civil Defence Department Fire Station, are also a part of the neighborhood

Figure 6.

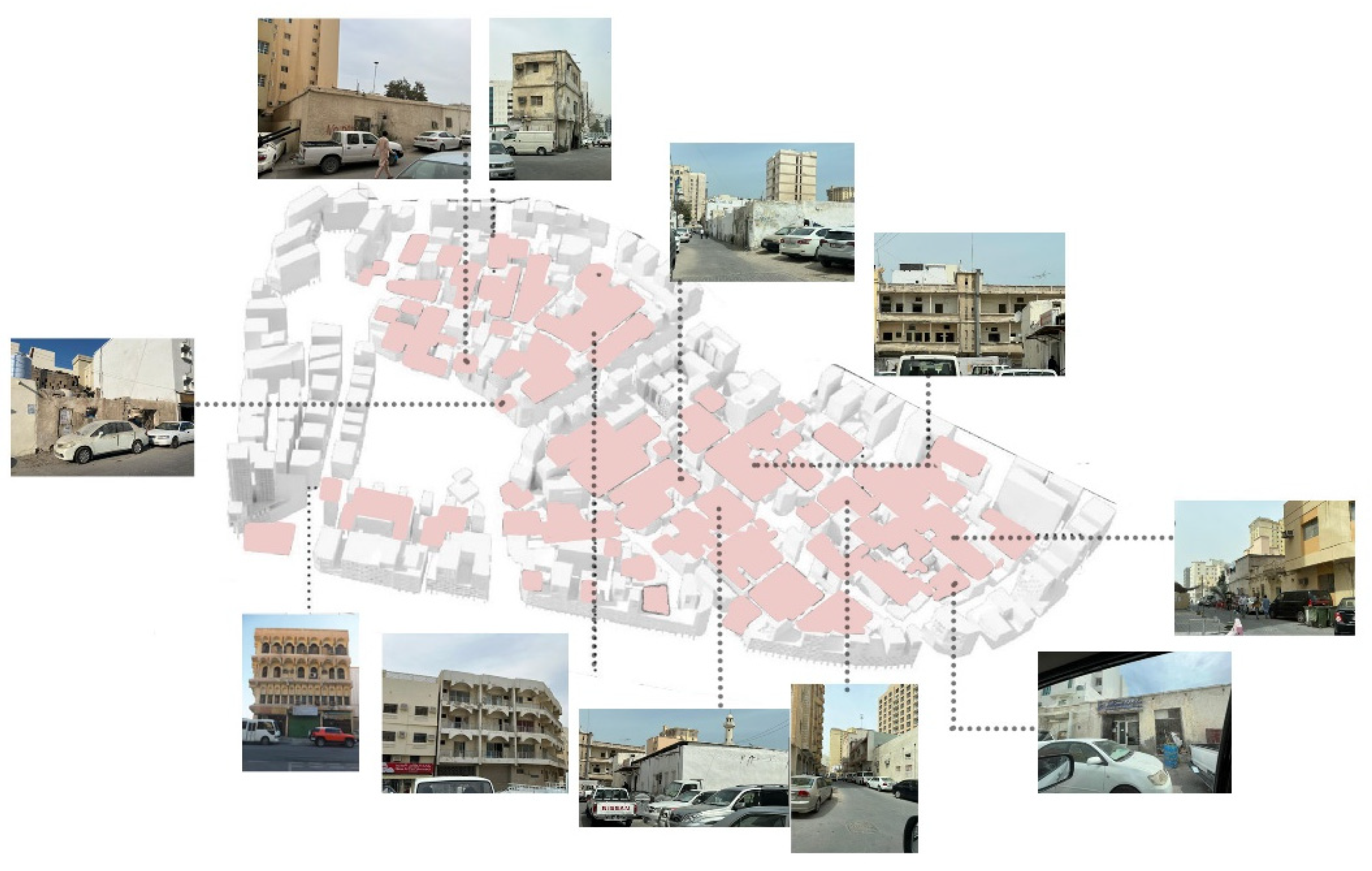

5.1.4. Building Conditions and Style

Buildings of varying physical conditions characterize the neighbourhood of Old Ghanim; some are in good condition whereas others are in poor condition and require to be demolished urgently. About 30% of the area in Old Ghanim is occupied by buildings in good condition, whereas buildings in bad condition

Figure 7 dominate 50% of the area. The remaining area of neighborhood houses are either under construction or demolished structures.

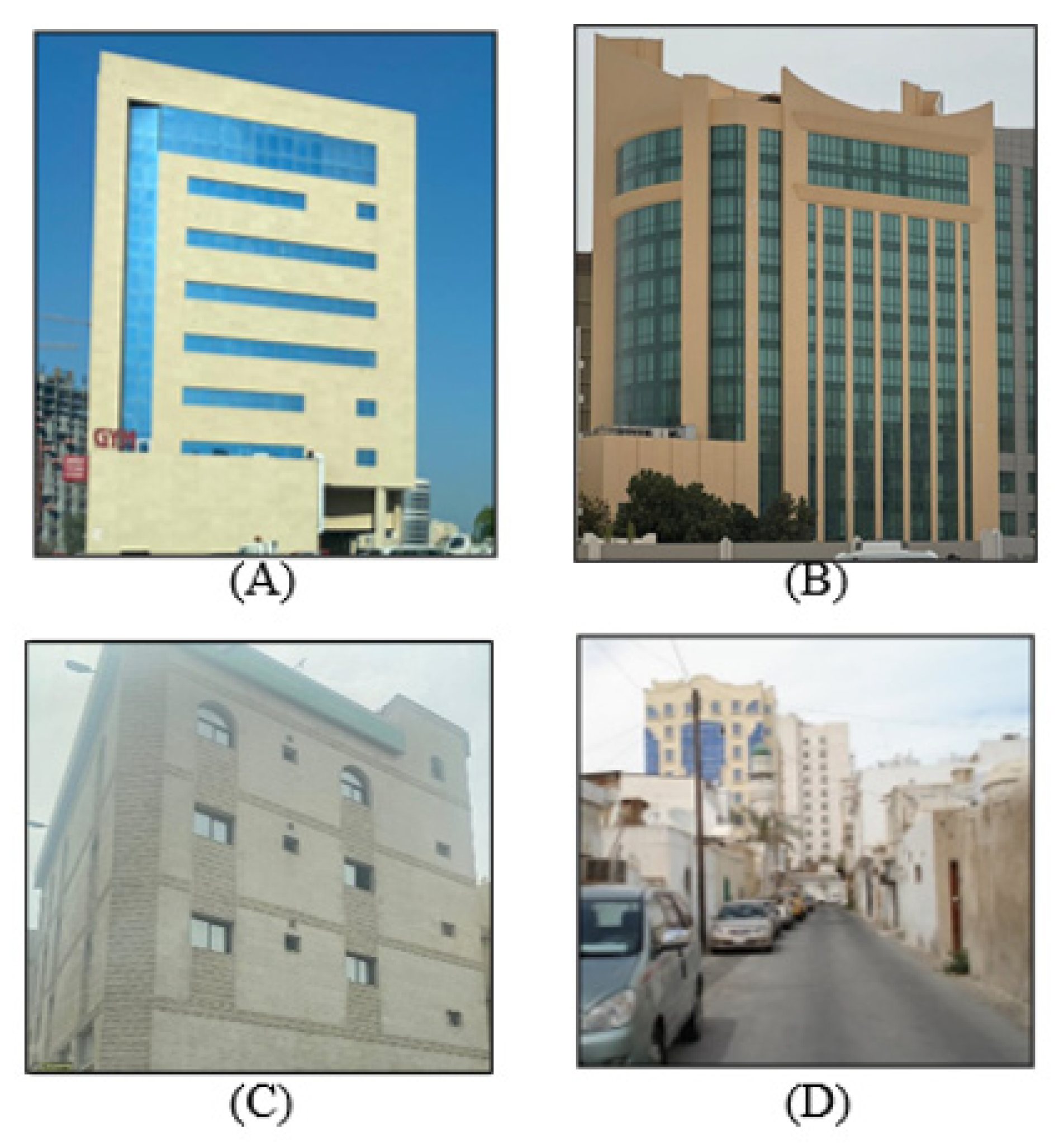

The study of the neighbourhood reveals that the buildings of Old Ghanim have been constructed in mixed building styles; some are characterized by modern architecture (

Figure 8A,B) whereas others depict a mixture of modern and early building styles (

Figure 8C). A few of the buildings show a traditional style with walkways, and some have an internal courtyard depicting another traditional building style, as shown in

Figure 8D.

5.2. Physical Elements Analysis

5.2.1. Neighborhood Entrance

Old Ghanim Neighborhood has three main entrance roads: Al Matar Street, Ras Abu Abboud expressway, and B Ring Road. These streets limit pedestrian access to the neighborhood. There are many vehicle access points, but none of these have a unique element that represents the neighbourhood’s identity characteristics that link the semi-public, neighborhood, and city life together. Al Ghanim Al Qadeem Park (Old Al Ghanim Park) functions as the neighbourhood center, thus promoting social interaction. Nevertheless, it lacks services that can enhance the community feeling amongst locals, and functions as a core point of attraction in the neighborhood. Some vacant lots can be used as neighborhood centers

Figure 9.

5.2.2. Buildings

The following series of photos represent a sample of the residential apartments in Old Ghanim. They are: newly constructed (

Figure 10A); renovated (

Figure 10B); under construction (

Figure 10C); traditional (

Figure 10D); or issued for demolition (

Figure 10E).

The building facades and functions have evolved from traditional, low-residential houses to high-rise commercial buildings on the surrounding streets. Despite the functionality of the buildings in the central part of Old Ghanim, the conditions are worse and require restoration. In some areas, decayed residential buildings have been replaced with multi-storey housing.

5.2.3. Streets

Three main roads define the Old Ghanim neighborhood (

Figure 11). On the north periphery of Old Ghanim runs the Ras Abu Abboud expressway. It is a significant artery connecting to the new Doha International Airport. The traffic flows smoothly and speedily there without any congestion most of the time. Old Ghanim has the renowned B ring Road in its East–South direction. This road is one of the biggest roads managing the heavy traffic flow throughout the day. Despite the effective traffic management of the Ras Abu Abboud Expy, the Al Matar Street (Airport Street), and the B Ring Road, the roads fail to offer convenience to pedestrians. Pedestrians cannot access the areas closest to them due to the lack of required sidewalks. The streets leading inside the neighborhood are narrow and dark. There are no signs or proper pavements. In addition, the buildings on the street are in a deteriorated condition and have no separation between the building zone and the road. Consequently, this situation goes against all safety and security measures, putting residents at risk. As shown in the following photos, Old Ghanim roads are in poor condition. There is a lack of traffic signs and pedestrian walkways.

6. Analysis and Findings

The following are the results of the observations conducted in the study area for blight indicators, as shown in

Table 2. These indicators are measured on good, minor, and major scales. With this scale, a rating of “good” indicates no blighting conditions, and a “major” rating indicates an extreme example of a blighting condition.

Out of 11 groups of blight indicators, two (2) are in good condition, four (4) are minor, and five (5) are major. This indicated that for 9 aspects, an urban regeneration intervention is required. The following is the assessment of the sustainability indicators on the physical elements of the neighbourhood as per the specified principles based on the constructed framework.

6.1. Street Network and Transportation

Traffic and street: the width and condition of the roads do not reflect the demand for vehicular activity, causing an increase in car accidents that hinder the flow even further in cross junctions and roundabout areas.

Street capacity is low (2–3 cars max): there is no directional flow control—the capacity is not enough for the current traffic flow suitable for the area.

Extreme shortage in parking spaces: continuous parallel parking on the streets creates further congestion. Small delivery trucks enter the passages, thus resulting in serious congestion and difficulties in manoeuvring safely and without interrupting the pedestrian flow.

Width of the street: no pedestrian path nor functional street separations are visible in the inner parts of the zone, creating excessive random pedestrian movement across the streets and causing interruptions between flows.

6.2. Building Physical Situation

The general overview of the area demonstrates the absence of regular individual or governmental maintenance overlooking the buildings. Thus, the physical condition of the building facades is relatively degraded, but they are not in a critical or dangerous situation. The outer building surroundings, which create an envelope for the area, are new (2008–2012). The outer buildings are commercial and services centres. The physical condition of the facades is modern, well-maintained aluminium cladding, with height variations from G+4 to G+7.

6.3. Environment

The separation between the street and pedestrian zones is in a degraded condition, where leftover construction barricades affect street use and image.

The location of the buildings is suitable in terms of use; however, the condition of the buildings is low and requires restoration.

The physical appearance and building forms are not consistent. Traditionally, buildings designed with a low budget were added during the 1980s, and old residential buildings were used as small commercial shops.

In a small number of the mixed-use areas, the condition of the exposed infrastructures is extremely decayed, due to their function not being in line with the original purpose. The sense of cultural heritage in terms of the design and architecture was manipulated to suit small businesses’ new functions, resulting in a disconnection from Qatar’s heritage.

The area suffers from poor hygiene in central regions and weak airflow due to narrow streets occupied by many small restaurants and trash.

There is no separation between construction clutter, potential hazards, and pedestrian and street space in demolished areas.

The area suffers from a lack of gradual transition between old and new building facades in visual connectivity.

7. Proposed Master Plan

7.1. Sustainable Goals and Principles

The study focused on investigating different sustainability principles and associated urban design strategies.

Table 3 shows the integration of the sustainable principles in terms of physical element regeneration in the developed master plan.

7.2. Proposed Master Plan

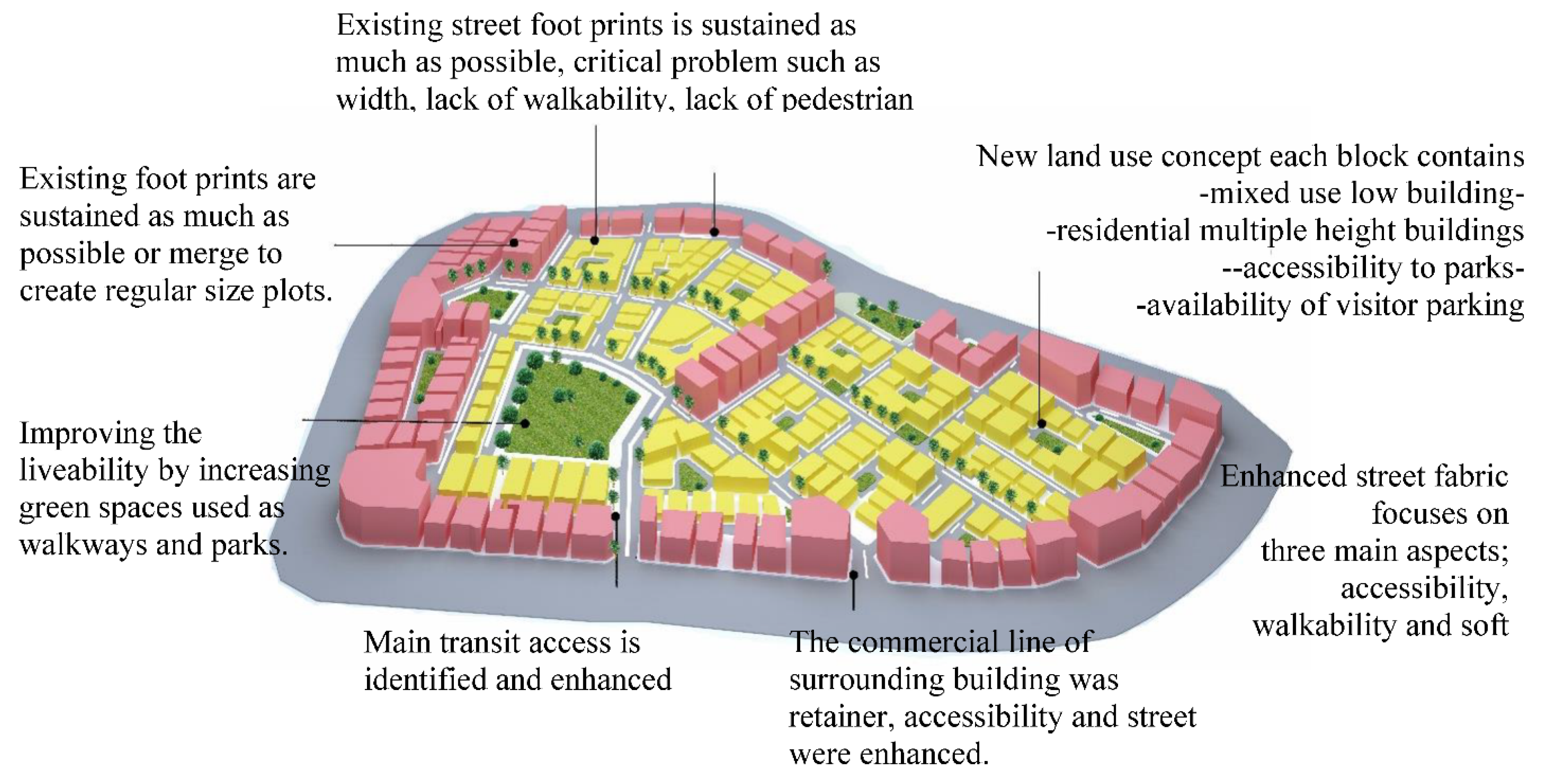

7.2.1. Street Network

The regeneration design development process considers various types of transportation, and encourages walkability and adequate parking space provisions. These solutions upgrade the street network and enhance commercial growth

Figure 12.

7.2.2. Efficient Streets for Vehicles

The hierarchical infrastructure approach of the roads and access points has been designed as a series of legible and efficiently connected routes to service residents’, businesses’, and visitors’ needs in three layers (main access roads, secondary roads, and tertiary roads). The following transportation links are represented throughout the district. The cohesive edge of the development consists of the commercial ring of previously developed buildings that interact both inwards, through secondary level backflow roads, and outwards, via the zone looking towards the primary roads. The maximum access quality is achieved through four main segments of the roads that vary in width and type based on the road category. The following features are pedestrian path, soft scape and shading elements, safe crossovers, and the size of parking lots. The efficiency of the access points is achieved by assessing the road width and car speed on the streets throughout the district. The assessment results help to change the poor urban environment by promoting walkability and reducing the car stops interrupting the traffic flow across the district.

7.2.3. Promotion of the Various Transportation Modes

A strategic path of visual continuity and accessibility between adjacent blocks leads to the main commercial line that vertically penetrates the area by creating an entire pedestrian street network. The walkable routes can be enhanced by identifying continuous pedestrian pathways where the major design aspect is safety and convenience measures. The following approach should be applied throughout the urban regeneration development area and considered one of the key approaches when moving forward in the urban design of blighted neighborhoods. The proposition of cycling lanes and new bus stations is another crucial element that helps optimize the load on the transport network within the area.

7.2.4. Adequate Parking

There are many vacant plots within the area without any specific land use. The following areas can be used as communal parking for private vehicles, thus solving chaotic and unregulated parking issues on the streets. It is necessary to envisage the exact location of the following parking spaces close to the residential blocks and the suitable sanitary gap that depends on the number of cars on the site to the distance to the building facade. This distance is required to prevent harmful fumes from penetrating living rooms through the windows.

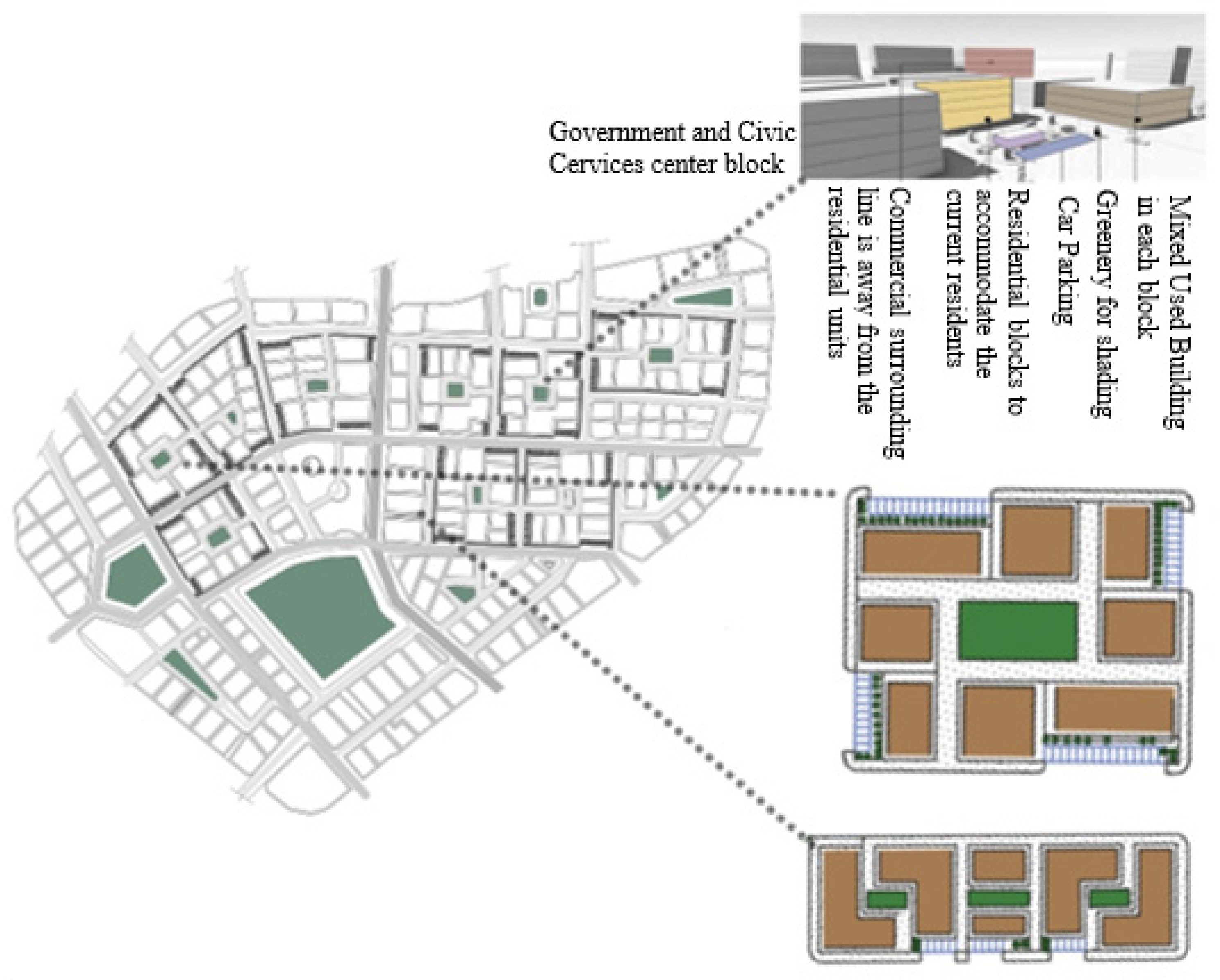

7.2.5. Building Form

Distinct, identifiable, self-need blocks guarantee that each urban cluster has its sense of privacy, and that the place is adapted for the user

Figure 13. Urban design solutions of neighbourhood blocks should support the standard walking distance to necessary daily facilities. The capacity of the master plan’s infrastructure has been scaled to accommodate the current density profile. For this reason, urban blocks must fit within the observed density requirements so the completed development can operate within its means. During the guidelines’ development, critical considerations have been taken into account to promote passive measurements of temperature control and wind flow. These considerations include:

Build up buildings and urban masses on the north and south side of the district to increase the shaded area and capture the northwestern wind.

The height reduction on the east and west side is established to improve ventilation and enhance cross ventilation of the west to the east line.

The creation of open green areas within the district is established to improve the air quality, temperature, and health conditions.

The construction of deep arcades on the main pedestrian routes is vital. The high-quality design of the buildings meets local architectural standards and expectations. In addition, the design solutions must respond to the detailed thermal comfort considerations and optimize internal organization to achieve maximum space efficiency.

7.2.6. Building Use

Horizontal land use: the district-scale creates clear area zoning with commercial and residential activities balanced by quantity and separated for functional convenience. Each residential plot is designed to have a direct interaction. Interaction of mixed-use and civic plots accessible to one another using strategic allocation. Vertical land uses of each block should be mixed-use to encourage vertical diversity and social mixing, as shown in

Figure 14.

7.2.7. Open Spaces: Green Community Concept

Green areas are distributed within the blocks as internal nodes, which increase the green spaces, and at the same time, serve as a social hub. These green nodes are interconnected and have access to the central green links. The increasing use of soft landscapes occurs along the main streets and corridors. Pedestrian corridors connect the main neighborhood park to the building blocks.

7.2.8. Neighborhood Entrance

The primary identity of the gateway is a vehicular entrance to the district marked by high-quality low-built forms and landscapes. Moreover, the following access points allow visual continuity to the inner parts of the central line of the district, as well as promoting access to the commercial developments within the area, as shown in

Figure 15.

7.2.9. Neighborhood Center

Old Ghanim park has been redesigned to serve as a neighborhood centre. The library, neighborhood service, and local businesses have been added to encourage resident engagement and gatherings. Wide local paths define the attraction of the centre for the visitors.

8. Case Studies Comparison

The following is an international, regional and local neighborhood with analyses of the applied strategies for declining urban blight. Local and international projects were chosen to achieve a benchmark for comparison with the implemented solutions and sustainable practices within the study area. A description of the chosen case studies is presented in

Table 4.

In the case studies, significant aspects were adapted to the context of the study area. Moreover, some negative consequences, which resulted in the neighborhoods, were avoided as per

Table 5 and

Table 6.

In the South of America, the neighbourhood of Illinois has applied reconstruction of streets, improved circulation, and connected the regeneration area with neighbouring areas within and surrounding the downtown region. The Deira Enrichment Project has uplifted and modernized one of Dubai’s longstanding residential districts and the emirate’s historic heart of commerce by creating a lively community built on traditions and historicity. Msheireb is a valuable example as it is situated within the B and C Ring Roads and is a notable example of an urban regeneration project that occurred in the downtown region of Doha based on sustainable principles.

The selected case studies demonstrated various land uses and transportation mechanisms which supported the proposed master plan of Old Ghanim. Hence, these studies helped obtain valuable design strategies employed in the current times to promote sustainability, as shown in

Table 6.

9. Conclusions

The sustainable urban regeneration of blighted neighbourhoods plays a significant role in urban development. The recovery of blighted sites may provide the city with many opportunities to reconstruct the physical structure, creating a healthier environment and achieving social, cultural, and economic sustainability.

Multiple stakeholders across the world devised and proposed various policies and methods based on their goals and the characteristics of each case. The intended primary audiences for these new policies are the local parties that guide and manage development. These policies are, to some extent, acceptable for the Qatari setting, according to the current study. The following policy lists are an aide-mémoire rather than a full list of permissible information, and they reflect good practice. The master plan incorporates various additional qualities for specific interventions and the concepts established in the urban design research. The following important challenges should receive priority for implementing rehabilitation and regeneration methods in Qatar’s blighted areas and embracing urban design concepts. Local parties that guide and manage development are the primary audience for these policies (

Table 7).

The following recommended points are concluded by compiling different concepts of blight, sustainability and urban regeneration:

Efficient street network;

High-density urban blocks;

Mixed land use;

Social interaction and engagement.

The fundamental principles of sustainable blight regeneration could guide sustainable blight regeneration projects. These principles can be implemented for the main elements of the neighborhood, such as streets, buildings, open spaces, neighborhood entrances, and social centres, using the land zoning development, accessibility, and architectural strategy.

Hence, it is true to say that incorporating the element of sustainability in the neighbourhood through a complex social fabric, structures, and mixed uses of land, enhances the city’s attraction; therefore, the plan for a community to attain sustainability must be adaptable while offering a clear direction. As a result, extensive planning based on the aforementioned principles is required to build a sustainable community.

10. Research Limitations and Future Recommendations

This study, however, is not without limitations. Although the study results provided a comprehensive initiative, the study area was only a Qatari blighted neighbourhood; therefore, the results may not represent other countries.

Future researchers might look at the long-term viability of urban regeneration programs in various circumstances and draw worldwide comparisons. They may also replicate the study and increase the secondary data utilized. As previously stated, the results of this study created a list of urban design features. It is a start toward attaining sustainable urban regeneration in Qatar, but further study is needed to achieve such a long-term aim in the country. Due to research constraints, the researchers used qualitative criteria for most assessment indicators. The authors propose that future scholars conduct further research utilizing quantitative factors to improve policies and initiatives’ accuracy, objectivity, and simplicity. Furthermore, expanding the scope of the research and increasing the total number of criteria and indicators in the model might be interesting in future studies when more resources are available. According to the scope of the current research, the researchers of this study investigated the physical component of sustainability.

The present study did not investigate sustainable regeneration in terms of economic and social factors for blighted neighborhoods. Therefore, analysing the climate and microclimate of the research area, Old Ghanim, is essential for this research since the regeneration of the neighborhood depends on the recommendations derived from environmental, social, and financial conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S.F. and V.M.M.; methodology, V.M.M. and S.B.G.; software, A.M.A.; validation, M.S.F., S.B.G. and A.M.A.; formal analysis, V.M.M.; investigation, V.M.M. and M.S.F.; resources, S.B.G.; data curation, V.M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, V.M.M.; writing—review and editing, M.S.F. and A.M.A.; visualization, V.M.M.; supervision, M.S.F.; project administration, A.M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This publication was made possible by the NPRP grant (NPRP 12S-0304-190230) from the Qatar National Research Fund (a member of Qatar Foundation). The statements made herein are solely the responsibility of the authors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mehanna, W.A.E.-H.; Mehanna, W.A.E.-H. Urban regenerationfor traditional commercial streets at the historical centers of cities. Alex. Eng. J. 2019, 58, 1127–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohebbi, T.A.; Mohebbi, T.G. Investigation and zoning of geo-environmental risk around the western edge of Khareshk village’s oil transmission line, Iran. Earth Sci. Inform. 2021, 14, 1367–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Rosa, D.; Privitera, R.; Barbarossa, L.; La Greca, P. Assessing spatial benefits of urban regeneration programs in a highly vulnerable urban context: A case study in Catania, Italy. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 157, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couch, C.; Dennemann, A. Urban regeneration and sustainable development in Britain: The example of the Liverpool ropewalks partnership. Cities 2000, 17, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turcu, C. Local experiences of urban sustainability: Researching Housing Market Regeneration interventions in three English neighbourhoods. Prog. Plan. 2012, 78, 101150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abass, A.S.; Kucukmehmetoglu, M. Transforming slums in Ghana: The urban regeneration approach. Cities 2021, 116, 103284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.J.; Zhao, D.X.; Zhu, J.; Darko, A.; Gou, Z.H. Promoting and implementing urban sustainability in China: An integration of sustainable initiatives at different urban scales. Habitat Int. 2018, 82, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.K.L.; Chan, E.H.W. The Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) Approach for Assessment of Urban Regeneration Proposals. Soc. Indic. Res. 2008, 89, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinhans, R.J. Housing policies and regeneration. In International Encyclopedia of Housing and Home; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 590–595. [Google Scholar]

- Korkmaz, C.; Balaban, O. Sustainability of urban regeneration in Turkey: Assessing the performance of the North Ankara Urban Regeneration Project. Habitat Int. 2020, 95, 102081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tin, W.J.; Lee, S.H. Development of Neighborhood regenerationin Malaysia through case study for middle income households in New Village Jinjang, Kuala Lumpur. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2017, 32, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yat, Y.; Zhao, P.; Sohail, M.T. The Morphology and Circuity of Walkable, Bikeable and Drivable Street Networks in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. J. Environ. Plan. B 2021, 48, 169–185. [Google Scholar]

- Yen, Y.; Wang, Z.; Shi, Y.; Xu, F.; Soeung, B.; Sohail, M.T.; Juma, S.A. The predictors of the behavioral intention to the use of urban green spaces: The perspectives of young residents in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Habitat Int. 2017, 64, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villagra, P.; Rojas, C.; Ohno, R.; Xue, M.; Gomez, K. A GIS-base exploration of the relationships between open space systems and urban form for the adaptive capacity of cities after an earthquake: The cases of two Chilean cities. Appl. Geogr. 2014, 48, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.W.; Shen, G.Q.P.; Wang, H. A review of recent studies on sustainable urban regeneration. Habitat Int. 2014, 41, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laprise, M.; Lufkin, S.; Rey, E. An indicator system for the assessment of sustainability integrated into the project dynamics of regeneration of disused urban areas. Build. Environ. 2015, 86, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala Benites, H.; Osmond, P.; Rossi, A.M.G. Developing Low-Carbon Communities with LEED-ND and Climate Tools and Policies in São Paulo, Brazil. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2020, 146, 04019025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlin, P.; Choay, F. Dictionnaire de l’Urbanisme et de l’Aménagement; Presses Universitaires de France: Paris, France, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Hakim, B.S. Mediterranean Urbanism: Historic Urban: Building Rules and Processes; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Brueckner, J.K.; Helsley, R.W. Sprawl and blight. J. Urban Econ. 2011, 69, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, S.; Maliheh, M. Urban Restoration: Definitions, Theories, Experiences, Universal Charters and Resolutions, Methods, 3rd ed.; University of Tehran Press (UTP): Tehran, Iran, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini, A.; Pourahmad, A.; Taeeb, A.; Amini, M.; Behvandi, S. Regenerationstrategies and neighborhood participation on urban blight. Int. J. Sustain. Built Environ. 2017, 6, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundtland, G.H.; Khalid, M. Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Devuyst, D. How Green Is the City? Sustainability Assessment and the Management of Urban Environments; New York Chichester, West Sussex; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso, J.M.; Andrews, R.; Jorda, V. Do Neighborhood regenerationprograms reduce crime rates? Evidence from England. J. Urban Econ. 2019, 110, 51–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Shen, G.Q.; Wang, H.; Hong, J.; Li, Z. Decision support for sustainable urban regeneration: A multi-scale model. Land Use Policy 2017, 69, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, H.; Lee, J.S.; Lee, S.-Y. Participatory Neighborhood Revitalization Effects on Social Capital: Evidence from Community Building Projects in Seoul. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2017, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riera Pérez, M.G.; Laprise, M.; Rey, E. Fostering sustainable urban regenerationat the neighborhood scale with a spatial decision support system. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 38, 440–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.C.; Huang, F.H.; Lin, S.E. Land assembly for urban development in Taipei City with particular reference to old neighborhoods. Land Use Policy 2018, 78, 555–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Holcomb, H.B.; Beauregard, R.A. Revitalizing Cities; Association of American Geographers: Washington, DC, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Marta, B.; Giulia, D. Addressing Social Sustainability in Urban Regeneration Processes. An Application of the Social Multi-Criteria Evaluation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Ryn, S.; Calthorpe, P. Sustainable Communities: A New Design Synthesis for Cities, Suburbs and Towns; New Catalyst Books: Gabriola Island, BC, Canada, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mehdipanah, R.; Marra, G.; Melis, G.; Gelormino, E. Urban regeneration, gentrification and health equity: A realist perspective. Eur. J. Public Health 2017, 28, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wing, C.K.; Wong, S.K. Externalities of Urban Regeneration: A Real Option Perspective. J. Real Estate Financ. Econ. 2012, 48, 546–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rohe, W.M. From Local to Global: One Hundred Years of Neighborhood Planning. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2009, 75, 209–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harger, J.R.E.; Meyer, F.M. Definition of indicators for environmentally sustainable development. Chemosphere 1996, 33, 1749–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromley, R.D.F.; Tallon, A.R.; Thomas, C.J. City Centre Regeneration through Residential Development: Contributing to Sustainability. Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 2407–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colantonio, A.; Dixon, T. Urban Regeneration and Social Sustainability: Best Practice from European Cities; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2011; p. 158. [Google Scholar]

- Tallon, A. Urban Regeneration in the UK, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, M. Sustainable urban design: Principles to practice. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. 2009, 12, 48–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, M. Urban indicators and the integrative ideals of cities. Cities 2006, 23, 170–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. The Framework of Social Sustainability for Chinese Communities: Revelation from Western Experiences. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2014, 2, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miri, S.H.; Miri, S.B.; Mohammad Rasoul, M. Urban Regenerationthrough Sustainable Development: A Case Study in Iran. Am. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2020, 13, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN-HABITAT. A New Strategy of Sustainable Neighborhood Planning. 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2014. Available online: http://unhabitat.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/5-Principles_web.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2022).

- Teed, J.; Condon, P.; Muir, S.; Midgley, C. Sustainable Urban Landscapes, Neighbourhood Pattern Typology. 2013. Retrieved 11 June 2014. Available online: http://www.jtc.sala.ubc.ca/projects/SDRI/typ.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2022).

- Falk, N.; Carley, M. Sustainable Urban Neighborhoods Building Communities That Last. 2012. Retrieved 10 June 2014. Available online: http://www.jrf.org.uk/sites/files/jrf/sustainable-urban-neighbourhoodsfull.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- Habib, F.; Hodjati, V.; Moztarzadeh, H. The Concept of Neighborhood and its Constituent Elements in the Context of Traditional Neighborhoods in Iran. Adv. Environ. Biol. 2013, 7, 2270–2278. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, H.; Grant, M.; Guise, R. Shaping Neighborhoods: For Local Health and Global Sustainability, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2003; pp. 293–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choguill, C.L. Developing sustainable Neighborhoods. Habitat Int. 2008, 32, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamble, T.; Bahadure, S. Neighborhood sustainability assessment in developed and developing countries. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 22, 4955–4977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghanmongabadi, A.; Hoşkara, Ş.Ö.; Shirkhanloo, N. Introduction to achieve sustainable neighborhoods. Int. J. Arts Commer. 2014, 3, 16–26. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, P.; Yen, Y.; Bailey, E.; Sohail, M.T. Analysis of Urban Drivable and Walkable Street Networks of the ASEAN Smart Cities Network. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2019, 8, 459. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2220-9964/8/10/459 (accessed on 24 May 2022). [CrossRef]

- Shandas, V.; Makido, Y.; Ferwati, M.S. Rapid Urban Growth and Land Use Patterns in Doha, Qatar: Opportunities for Sustainability? Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. Res. 2017, 1, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Siddiqi, A.; Dawe, R. Qatar’s oil and gasfields: A review. J. Pet. Geol. 2007, 22, 417–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrouh, H.; Ismail, A.; Cheema, S. Demographic and health indicators in Gulf Cooperation Council nations with an emphasis on Qatar. J. Local Glob. Health Perspect. 2013, 2013, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, R.; Carter, R. Mapping the Growth of an Arabian Gulf Town: The Case of Doha, Qatar. J. Econ. Soc. Hist. Orient 2017, 60, 420–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- County, F. Fairfax County Comprehensive Plan. 2013. Available online: chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/viewer.html?pdfurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.fairfaxcounty.gov%2Fplanning-development%2Fsites%2Fplanning-development%2Ffiles%2Fassets%2Fdocuments%2Fcomprehensiveplan%2Fplanhistoric%2F2011%2Farea4%2Ffranconia%2F2-12-2013.pdf&clen=3117414&chunk=true (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Aly, S.A. Downtown Redevelopment by Applying New Urbanism Principles (Case Study: Alexandria Downtown, Egypt). Am. J. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2015. Available online: chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://rspublication.com/ajscs/jan15/12.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Buisness, A. First Phase of Plan to Regenerate One of Dubai’s Oldest Districts Near Complete. 2020. Available online: https://www.arabianbusiness.com/gcc/uae/448478-first-phase-of-plan-to-regenerate-one-of-dubais-oldest-districts-near-complete (accessed on 6 April 2022).

- Min-Allah, N.; Alrashed, S. Smart campus—A sketch. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 59, 102231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alawadi, K. Rethinking Dubai’s urbanism: Generating sustainable form-based urban design strategies for an integrated neighborhood. Cities 2017, 60, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedmann, F.; Mirincheva, V.; Salama, A. Urban Reconfiguration and Revitalization: Public Mega Projects in Doha’s Historic Center. Open House Int. 2013, 38, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, R.; Shaaban, K. Rebuilding Old Downtowns: The Case of Doha, Qatar. In Proceedings of the REAL CORP, Schwechat, Austria, 14–16 May 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Al Malki, A. Investigating Livability of Mixed-Use Neighborhood Case Study of Najma in Doha, Qatar: A Thesis in Urban Planning and Design. Master’s Thesis, Qatar University, Doha, Qatar, 2017. Available online: http://qspace.qu.edu.qa/handle/10576/5801 (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Agency, E.N. Ithra Dubai Launches One Deira at Deira Enrichment Project. 2021. Available online: https://www.zawya.com/en/business/ithra-dubai-launches-one-deira-at-deira-enrichment-project-i3wge6mu (accessed on 6 April 2022).

- Awad, J.; Jung, C. Extracting the Planning Elements for Sustainable Urban Regeneration in Dubai with AHP (Analytic Hierarchy Process). Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 76, 103496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Ahmad, A.; Aliyu, A.A. Strategy for shading walkable spaces in the GCC region. J. Urban Regen. Renew. 2021, 14, 312–328. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Urban sustainability assessment frameworks. Source: Authors, elaborated from Wang, 2014.

Figure 1.

Urban sustainability assessment frameworks. Source: Authors, elaborated from Wang, 2014.

Figure 2.

Theoretical framework. Source: Author.

Figure 2.

Theoretical framework. Source: Author.

Figure 3.

Freej Old Ghanim main and secondary connections to the surrounding neighborhoods. (Source: Authors).

Figure 3.

Freej Old Ghanim main and secondary connections to the surrounding neighborhoods. (Source: Authors).

Figure 4.

Typical traffic in Old Ghanim at 5 p.m. (Left) and 8 p.m. (Right). Source: Google Maps.

Figure 4.

Typical traffic in Old Ghanim at 5 p.m. (Left) and 8 p.m. (Right). Source: Google Maps.

Figure 5.

Ten minute walking distance in Freej Old Ghanim (Source: iso4map).

Figure 5.

Ten minute walking distance in Freej Old Ghanim (Source: iso4map).

Figure 6.

Freej Old Ghanim existing land use map (Source: edited from MME).

Figure 6.

Freej Old Ghanim existing land use map (Source: edited from MME).

Figure 7.

Old Ghanim building with poor conditions map (Source: ARUS, modified by the Autor).

Figure 7.

Old Ghanim building with poor conditions map (Source: ARUS, modified by the Autor).

Figure 8.

The study area’s building style (A,B): modern style: (C): mixture of modern and early building styles, (D): traditional style. (Source: Authors).

Figure 8.

The study area’s building style (A,B): modern style: (C): mixture of modern and early building styles, (D): traditional style. (Source: Authors).

Figure 9.

Map of the vacant lots in Old Ghanim for potential neighborhood centers (Source: Authors).

Figure 9.

Map of the vacant lots in Old Ghanim for potential neighborhood centers (Source: Authors).

Figure 10.

Types of residential buildings in Old Ghanim. (A): newly constructed, (B): renovated, (C): under construction, (D): traditional, (E): issued for demolition. (Source: Authors).

Figure 10.

Types of residential buildings in Old Ghanim. (A): newly constructed, (B): renovated, (C): under construction, (D): traditional, (E): issued for demolition. (Source: Authors).

Figure 11.

Street ap and street conditions of Old Ghanim (Source: Authors).

Figure 11.

Street ap and street conditions of Old Ghanim (Source: Authors).

Figure 12.

Proposed Network (Source: Authors).

Figure 12.

Proposed Network (Source: Authors).

Figure 13.

Strategies of Block Components and Proposed Open Spaces (Source: Authors).

Figure 13.

Strategies of Block Components and Proposed Open Spaces (Source: Authors).

Figure 14.

Proposed land-use map (Source: Authors).

Figure 14.

Proposed land-use map (Source: Authors).

Figure 15.

Gate Points and Accessibility map (Source: Authors).

Figure 15.

Gate Points and Accessibility map (Source: Authors).

Table 1.

Urban design principles adopted in the current research and their sustainable indicators following the blight indicators.

Table 1.

Urban design principles adopted in the current research and their sustainable indicators following the blight indicators.

| Sustainable Urban Design Principle | Sustainable Indicator | Blight Indicator |

|---|

Urban identity and vitality

[49] | Well maintained local cultural centers. | - -

Incompatibility of the historical surroundings; - -

Abandoned architecturally and culturally valuable buildings.

|

| Housing and Setting welfare [5] | - -

Preserved unoccupied houses and commercial amenities; - -

Preserved depreciated houses and commercial amenities.

| - -

Unmaintained property; - -

Violations to building code.

|

| Improvement of quality of life [5] | - -

Roads in good condition; - -

Provision of pedestrian roads.

| - -

Unsanitary; - -

Unsafe Conditions.

|

| Green open space | - -

Open space/active greens per dwelling which are easily accessed and of quality; - -

Active greens/open space per development area.

| The poor condition of urban facilities such as green spaces. |

| Public spaces quality [18] | - -

The place identity was preserved; - -

Mix usage space was dedicated; - -

Heritage buildings and monuments.

| The poor condition of public spaces. |

| Neighborhood relevance into the wider community [50,51]. | - -

Main roads on the periphery; - -

Reduced internal roads; - -

External connections.

| Insufficient street network. |

Interaction and gathering

[50,51] | - -

Parks and other green spaces; - -

Common meeting place for residents.

| The poor condition of urban facilities. |

Environmental quality

[51] | - -

Boundaries that are efficiently defined should exist; - -

Well maintained Neighborhood central place should be present; - -

Presence of current services and facilities

| - -

Drawings and litter; - -

Safety; - -

Environmental hazards.

|

Efficient street network

[51,52,53] | - -

Walking and cycling-friendly streets; - -

Encouragement of public transportation; - -

Strong interconnection of street hierarchy; - -

Sufficient parking area; - -

Motorized and pedestrian traffic to be separated; - -

Public transit system or nodes to be within proximity; - -

Pedestrian network; - -

Street connectivity; - -

Vehicular entry and exit routes; - -

Separation between pedestrian and motorized traffic; - -

Reduce parking footprint; - -

Traffic calming measures; - -

Sidewalk completeness; - -

Proximity to public transit nodes/system; - -

Cities with orthogonal street grids, high street density, junction density, and fewer cul-de-sacs provide excellent access to destinations.

| - -

Lack of transportation; - -

Insufficient Infrastructure; - -

Defective Parking.

|

Upgrade local environments

[18] | Urban quality and density to maintain a balance. | Outdated density. |

Table 2.

Blight indicators of Old Ghanim. Source: Author.

Table 2.

Blight indicators of Old Ghanim. Source: Author.

| Blight Indicator | Status | Comments | Site Pictures |

|---|

- -

Incompatibility of the history surrounding architecturally and culturally valuable abandoned buildings.

| minor | - -

Old (Dar Alketab). - -

Does not attain historic or essential buildings which need preservation.

| ![Sustainability 14 06963 i001 Sustainability 14 06963 i001]() |

- -

Unrecognized property violations. - -

Local building code compliance.

| major | - -

Many of the buildings are in poor and unsafe conditions.

| ![Sustainability 14 06963 i002 Sustainability 14 06963 i002]() |

- -

Faulty of the layout of the lots.

| good | - -

No large lots. Pedestrian-friendly grid network.

| ![Sustainability 14 06963 i003 Sustainability 14 06963 i003]() |

- -

Uninhibited building.

| major | - -

The local residents have abandoned many buildings.

| ![Sustainability 14 06963 i004 Sustainability 14 06963 i004]() |

- -

Site maintenance. - -

Unsanitary and unsafe conditions. - -

Deterioration of the site improvements.

| major | - -

Many abandoned buildings hold trash and construction waste. - -

Many buildings issued as deterioration sites have still not been removed.

| ![Sustainability 14 06963 i005 Sustainability 14 06963 i005]() ![Sustainability 14 06963 i006 Sustainability 14 06963 i006]() |

| The poor condition of urban facilities such as green spaces. | good | Old Ghanim park is well maintained and does not need significant regeneration. | ![Sustainability 14 06963 i007 Sustainability 14 06963 i007]() |

| Unoccupied lots. | minor | - -

Not functioning vacant lots.

| ![Sustainability 14 06963 i008 Sustainability 14 06963 i008]() |

| Insufficient street network. | Minor | - -

Main roads exist on the periphery but are not well connected to the internal roads - -

Internal roads are well organized on a grid - -

Compact pedestrian network

| ![Sustainability 14 06963 i009 Sustainability 14 06963 i009]() |

- -

Drawings and litter. - -

Sanitation. - -

Safety. - -

Environmental hazards.

| Major | - -

Poor street furniture. - -

Poor waste management. - -

Absence of sidewalks. - -

No separation between vehicular and pedestrian zones. - -

Litter and waste spread, such as

| ![Sustainability 14 06963 i010 Sustainability 14 06963 i010]() |

| | |

graffiti on the walls stating “No parking”, among other scattered writings.

- -

Lack of proper signage.

| ![Sustainability 14 06963 i011 Sustainability 14 06963 i011]() |

- -

Transportation infrastructure/defective parking.

| minor | - -

Public transportation exists, but there are few stations in poor condition. - -

Many parked cars are on the pedestrian sidewalks. Weak allocation and management of parking spaces.

| ![Sustainability 14 06963 i012 Sustainability 14 06963 i012]() ![Sustainability 14 06963 i013 Sustainability 14 06963 i013]() |

| Outdated density. | major | Many foreign workers occupying inadequate residential units. | ![Sustainability 14 06963 i014 Sustainability 14 06963 i014]() |

Table 3.

Incorporation of the sustainability principles in urban development.

Table 3.

Incorporation of the sustainability principles in urban development.

| Sustainable Goal | Principle | Applied Urban Design Strategies |

|---|

| Efficient Street Network | Efficient streets for vehicles. | - -

Road hierarchy is highly interconnected with arterial routes and local streets. - -

Provision of sufficient parking spaces.

|

| Promote different transportation modes leading to the reduction of private cars. | - -

Walkable and cyclist-friendly streets. - -

Encouragement of public transport.

|

| Functional, flexible, and aesthetic street furniture. | - -

Provision of a clear and readable signage system. - -

Availability of street furniture based on the intensity of activity within a particular area. - -

Street elements are carefully placed to create unobstructed paths for pedestrians without creating hazards.

|

| High Density | The concentration of people and their activities. | Relationship between land use, the form of the cities, and travel patterns. |

| Intensification of existing urban areas | Well-designed and organized high-density neighborhood. | Urban blocks which vary in size and activities. |

| Mixed Land Use | Provision close proximity and access to the public services. | Activities should be designed compatible, well balanced and close to each other

Inappropriate locations |

| Support mixed-use communities. | - -

Combination of residential, commercial, industrial, office, and other land-uses on site. - -

Avoid single-use zoning.

|

| Compacted mixed uses. | - -

Mixed horizontal and vertical land uses. - -

Range of compatible activities.

|

| The flexibility of the development to adapt over time. | - -

Ensure convenient satisfaction of the uses within the neighbourhood based on the residents’ everyday needs.

|

| Social Mix | Promotion of cohesion and social interaction among different classes. | - -

Providing different types of housing. - -

Spatial distribution of poor households.

|

| Efficient Street Network | Efficient streets for vehicles. | - -

Road hierarchy is highly interconnected with arterial routes and local streets. - -

Provision of the sufficient parking spaces.

|

| | Promote different transportation modes leading to the reduction of private cars. | - -

Walkable and cyclist-friendly streets. - -

Encouragement of public transport use.

|

| | Functional, flexible, and aesthetic street furniture. | - -

Provision of a clear and readable signage system. - -

Availability of the street furniture based on the intensity and activity within a particular area. - -

Street elements are carefully placed to create unobstructed paths for pedestrians without creating hazards.

|

| High Density | The concentration of people and their activities. | The relationship between the land uses that form the cities, and travel patterns. |

| Ensure accessibility to equitable urban opportunities | Providing plots in different sizes and with various regulations. | |

| Limited Land Use Specialization | Adjust/limit the use of functional zoning. | - -

Building height regulation based on the different zone types and location-regulated lot coverage.

|

| Combine compatible land uses into one block. | - -

Limitation of the single function blocks.

|

Table 4.

Description of the chosen case studies.

Table 4.

Description of the chosen case studies.

| Case Study | Type | Significance to Study |

|---|

| Springfield Downtown Redevelopment, US | Urban regeneration plan for the resurgence of the downtown and removal of blight. It aims to transform the area into

a mixed-use, easily accessible, and interconnected place

[58]. | It has similar features of blight to the neighborhoods situated in Downtown Doha

[59]. |

| Deira Enrichment Project, Dubai | The reinforcement and redevelopment of the historic economic centre in Dubai through a sustainable urban regeneration project [60]. | The speed of economic development in Dubai is parallel to Qatar’s [61]. With the development in the economic sector, old infrastructure in Dubai was shattered by disruptions in the local economic development and the weakness of the urban population residing in Dubai. As a result, the vitality and the hustle and bustle of the city center were badly affected [62]. |

| Musheireb Properties, Doha | Urban regeneration project seeking to renew the neighbourhood with better urban design policies and guidelines

[63]. | The area falls within the same zone as the study region and is similar to the earlier uses and functions that prevailed before Msheireb went through urban regeneration. The region adopted sustainable principles and accomplished LEED certifications. |

Table 5.

Adopted and Avoided Design Principles.

Table 5.

Adopted and Avoided Design Principles.

| Case Study | Adopted Principle | Avoided Consequences |

|---|

Msheireb

Properties | Corresponds to international and domestic sustainability standards.

Adequately-connected pedestrian networks in the site [64]. | The old and urban fabric of Msheireb was entirely damaged.

No consideration was given to the earlier residents.

There is inadequate diversity in housing alternatives.

Gentrification was endorsed [65]. |

| Springfield Downtown Redevelopment | Enhances streets, parks, streetscapes and open spaces.

Develops or rehabilitates parking facilities.Encourages different land uses [59]. | Presently, the neighbourhood appears to be dominated by commercial, rather than residential, activities [58]. |

| Diera Enrichment Project | - -

A vibrant mix of residential, commercial, retail, and hospitality offerings. - -

Rejuvenates Dubai’s historic heart of commerce and original community centre while preserving its unique cultural characteristics. - -

Integrated central transport station [ 66].

| Only developed the waterfront area. The link between the natural growth of the city to revitalize the Deira area for the economic success and

being a densely populated area is broken. There is often quite a lot of traffic in Deira, especially during peak hours with a shortage of parking spaces [67]. |

Table 6.

Adopted Design Strategies to Old Ghanim Neighborhood.

Table 6.

Adopted Design Strategies to Old Ghanim Neighborhood.

| Case Study | Design Strategy |

|---|

| Msheireb Properties | Integrate transportation network in the region to reduce dependence on the use of cars.

Offer high-quality public arena.

Safeguard neighbrhood identity and diversity. |

| Springfield downtown Redevelopment | Develop an integrated transportation network in the region.

Offer residential diversity.

Offer a combination of commercial activities.

Develop intermodal connectivity. |

| Diera Enrichment Project | It is a connected, vibrant, and diverse space.

Retain the urban grain of the old city.

Connect all plots via narrow alleys. |

Table 7.

Urban Design Principles for achieving sustainable policies.

Table 7.

Urban Design Principles for achieving sustainable policies.

| Urban Design Principles | Sustainable Policies |

|---|

| Urban Form | Respond to the city’s “scale and massing” of buildings as well as their “character.”

Ensure that the size and enclosure of public areas, the continuity of the building line and urban grid, road layout, and block and plot size are all considered. |

| Public Realm and Open Space | Public space plans of high quality which are open.

Encourage busy ground-level frontages. Sustainable shading strategies for the GCC regions described by Ahmad et al. (2021) can be adopted to facilitate pedestrian activities [68] |

| Mixed-use | The combination of residential, commercial, and recreational activity fostered the blending of tenures and designs that incorporate a range of tenure types. |

| Connection, Movement, Walkability | Encourage walking and cycling by providing enough space, networks, and facilities.

Through the street hierarchy, ensure that road layouts promote safe, simple, and direct pedestrian mobility and establish a network of beautiful, well-connected public areas. |

| Architecture Design | High-quality architecture that is sensitive to its surroundings.

Prevent out-of-scale usage and structures (including tall buildings).

Make active peripheral frontages, such as storefronts. |

| Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).