Abstract

Misinformation on sustainability has become a widespread phenomenon in many different contexts. However, relatively little is known about several important determinants of belief in misinformation, and even less is known about how to debias that belief. The present research proposes and investigates a new effect, the half-truth effect, to explain how message structure can influence belief in misinformation. Two survey-based experiments were conducted to show that people exhibit greater belief in a false claim when it is preceded by a true claim, even if the two claims are logically unrelated. Conversely, when a false claim is presented before the true claim, it reduces the belief in the entire statement. Experiment 1 shows the basic half-truth effect. Experiment 2 investigates an individual difference, propensity to believe meaningless statements are profound, which impacts the half-truth effect. Both experiments also investigate debiasing of the false information. The results of the experiments were analyzed using analysis of variance and regression-based mediation analysis. Results show that belief in misinformation is dependent on message structure, and show that the order in which true and false elements are presented has a strong influence on belief in sustainability misinformation. Finally, we present a discussion of how policy makers can use these findings to identify those people who are most likely to be swayed by the misinformation, and then design responses to debias sustainability misinformation.

1. Introduction

“The lie which is half a truth is ever the blackest of lies.”[1] (St. 8).

Is Tennyson’s observation accurate? Are half-truths more insidious than lies that are not associated with truths? If so, what are the boundary conditions of the half-truth effect? What are the implications of the half-truth effect for understanding misinformation campaigns more generally, and how can people protect themselves from the half-truth effect? The present research addresses these questions by proposing that consumers process misinformation in a way that conforms to Tennyson’s quote. We call this new phenomenon the half-truth effect and offer some insights into the moderation of the new proposed half-truth effect.

Misinformation is defined as information that is initially presented as valid but is subsequently shown to be incorrect [2,3]. The phenomenon of misinformation has become widespread in online environments [4,5], as exemplified by the fact that one in four Americans have admitted to sharing false information online [6], and that falsehood spreads more quickly than truth on social networking sites like Twitter [7]. In recent years, digital misinformation has been influencing the public’s perceptions of scientific topics [8,9,10,11,12,13]. For instance, false accounts regarding the safety of vaccines [14,15] and climate change [2,3] have been gaining more online support. The rapid spreading of false information has been posing a growing risk to the health of the public and the planet [16,17], so much so that the World Economic Forum has classified it among the most relevant dangers to modern society [18].

Half-truth is defined as “a statement that mingles truth and falsehood with deliberate intent to deceive” [19]. However, it may not be that simple. The current work proposes and investigates a new effect, the half-truth effect, that hypothesizes that it is both message structure and veracity of the elements of the argument that can influence belief in misinformation on topics of sustainability and genetically modified organisms (GMOs). Additionally, we analyze a personal characteristic that influences the half-truth effect and a potential debiasing technique to provide a roadmap for policy makers to counteract misinformation.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 provides an overview of the literature on misinformation. Section 3 defines the proposed novel half-truth effect, specifies how it differs from alternative accounts of misinformation, and introduces the proposed moderator, BSR (bullshit receptivity) [20]. Section 4 details how the half-truth effect is particularly relevant for the spreading of false information on sustainable living, including the use of GMOs. Section 5 discusses how Cialdini’s et al. [21] Poison Parasite Counter (PPC) may interact with the half-truth effect to reduce belief in false information on sustainability topics. Section 6 details materials and methods used in the two experiments. Section 7 provides the procedure, results, and analyses of both experiment 1 and experiment 2. Section 8 provides a discussion of the findings. Section 9 discusses theoretical implications, practical implications, and limitations, and Section 10 provides a summary conclusion.

2. Literature Review and Gap Analysis

While there is an entire stream of research investigating how algorithms can be used to identify (and potentially remove) false information across many different online platforms [22], a separate and important stream of research looks at how humans process and use that false information. Given that the artificial intelligence algorithms are not likely to completely remove false information from our online sources, this paper focuses on how humans process that information once it is encountered.

Previous work on the processing of misinformation has focused on psychological antecedents that lead individuals to believe in false claims. For instance, research has found that political ideology shapes belief in false claims [23]. Specifically, both democrats and republicans are more likely to believe false news that reports undesirable behavior among members of the opposing party (i.e., the “outgroup”), and republicans are more likely to believe and share apolitical fake news [24]. Moreover, an additional stream of research that focuses on the role of reasoning type has found that people who are more reflective are less likely to believe false news, irrespective of their political affiliation [25]. Previous work has also found that a key influence on belief in false claims is familiarity [25]. In both laboratory settings and more naturalistic exposures (text messages), repetition increases the likelihood that false information will be perceived as true [26]. Repetition, also known as the illusory truth effect, is so powerful a force that repeated false statements were perceived as more truthful than non-repeated statements even when the false statements contradicted the participant’s prior knowledge [27]. Similarly, a single prior exposure to a fake news headline enhances belief in the headline at a later point in time [28]. It has been suggested that repetition is effective in making false statements appear as true because the repetition increases the processing fluency of the statements [29,30].

Belief in misinformation is also associated with cognitive abilities, such that individuals with lower intelligence scores are more likely to endorse political misbeliefs [31] and those who are less prone to engage in analytical reasoning are more likely to believe false news headlines [25,32,33]. Moreover, belief in false information is also associated with religious fundamentalism [33], delusionality [33], and bullshit receptivity [25]. In another context, when the hypothesized antecedents are tested within the same model, three distinct individual differences (higher spirituality, higher narcissism, and lower analytical thinking) have been shown to predict beliefs in both COVID-19- and non-COVID-19-related misinformation [34]. However, other types of individual differences (e.g., need for cognitive closure) do not appear to diminish the impact of repetition on belief in false information [35].

So far, research has focused on individual differences and categorical message content, but not on how the message is structured. That is, although previous work has identified several psychological factors that influence belief in misinformation, the literature is currently silent on how the underlying message structure may influence belief in misinformation. This potential gap in the literature is important because message structure may be more controllable than repetition by a bad actor attempting to portray a piece of false information as true. Thus, it is important for policy makers to understand how message structure and order of message components work to influence believability of a false claim.

3. The Half-Truth Effect

To close this gap in the literature, this work seeks to examine the role of message structure in shaping perceived truthfulness of misleading claims. We contend that the structure of the information contained in the message will elicit (or not) a greater belief in the veracity of false information. In deference to the Tennyson quote that inspired this hypothesis, we call this phenomenon the half-truth effect. We propose that belief in misinformation will be shaped by not only the dictionary definition—a half-truth contains both true and false information [19]—but also by the order of the true and false claims that make up the piece of false information. Specifically, we contend that individuals will be more likely to believe in a false message when the message starts with a true piece of information and then uses logical terminology to tie it to an unrelated false piece of information. Conversely, individuals will be less likely to believe misinformation when the false information is presented first, even when followed by a true element.

There are several reasons for suspecting that the half-truth effect occurs in this way. First, it has been shown that emotions induced by an a priori irrelevant event carry over to influence a subsequent (unrelated) economic decision [36]. In the same way, we might expect that presenting a true claim should encourage message recipients to perceive the communicator as more credible and trustworthy [37,38,39], and those perceptions of creditability and trustworthiness may carry over to the false statement presented next. Furthermore, receiving a true claim first should increase open-mindedness and encourage recipients to entertain the possibility that the subsequent claims are also valid [40,41]. This has been shown in another context such that consumers who have been primed to make supportive elaborations about an unrelated series of propositions (e.g., primed into an acquiescence mindset) are more likely to be positively influenced by an unrelated advertisement encountered next [42,43]. Receiving a true claim first may also elicit an acquiescence mindset that encourages people to accept the subsequent claim as true. Extrapolating these findings into the realm of misinformation, it is hypothesized that the order of presentation should matter to the ultimate perceived truthfulness of a presented message.

That is, a message should be perceived as more truthful when it begins with a statement that is true (even when it is followed by an unrelated false statement). Conversely, the opposite order of information presentation should eliminate the half-truth effect such that presenting a false claim first should reduce perceptions of source credibility and induce the naysaying mindset, resulting in a lower perceived truthfulness of the message. Hence, the order in which claims of mixed validity are presented should be an important moderator of the half-truth effect.

If this is true, then the half-truth effect is dependent on the initial evaluation of the primary element of the message. Thus, the ability for one to discern whether something is fact or fiction becomes an important moderator to consider. By default, humans want to trust things [44]. However, individuals vary in their ability to discern information that is profound from information that does not contain meaning [20]. That is, random information and buzzwords that are combined into a nonsense statement yet formatted with a standard syntactic structure are perceived to be profound by a segment of the population. Pennycook and colleagues [20] call this pseudo-profound bullshit. Drawing inspiration from quotes by Deepak Chopra, Pennycook and colleagues have validated a measure for bullshit receptivity (BSR; example items “Hidden meaning transforms unparalleled abstract beauty”, “Good health imparts reality to subtle creativity”) and have shown that those who are receptive to pseudo-profound bullshit are not merely indiscriminate in their thoughts, but rather do not discern the deceptive vagueness of the statement. Thus, they are more prone to believe statements as true if the syntax implies profundity.

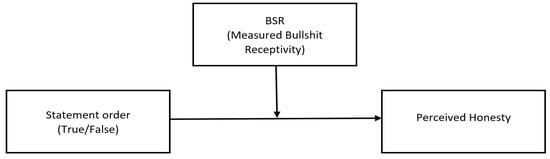

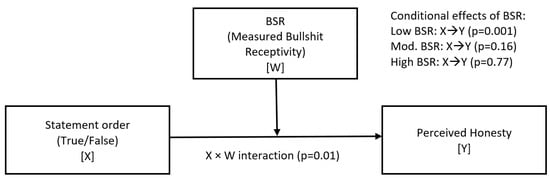

These results can highlight a potential moderator of the half-truth effect. If one is focused on syntax and not actively considering the validity of the initial statement, then there is no reason to assume that the information provided is anything but truthful. Therefore, those who readily accept statements as truthful without a second thought (i.e., high BSR) are unlikely to experience the half-truth effect because they are equally likely to believe both true and false statements. In contrast, those who are low in what Pennycook terms BSR (bullshit receptivity) are more likely to experience the half-truth effect as they will seek to establish the validity of the argument early on and then hold onto that conclusion. The proposed model is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The half-truth effect model: Statement order is hypothesized to be moderated by bullshit receptivity (BSR), such that the half-truth effect will be evident among those who have a low BSR, but not among those who have a high BSR.

Although the illusory truth effect [45] and this newly proposed half-truth effect may sound similar in their name, they are really quite different in application. First, there is the matter of structure. The illusory truth effect focuses on a singular statement which (through repetition) forms a mental foothold on which the individual builds the illusion of knowledge, or in this case, truth [46]. Conversely, the half-truth effect examines how consumers interpret truth when they encounter multiple statements in tandem. This difference is important because even in social media with limited character counts, messages are often complex, multi-part arguments rather than the singular statement that forms the basis of the illusory truth effect. For this reason, it is important that we understand how message receivers interpret statements that combine true and false elements.

Second, the illusory truth effect relies on repetition to increase belief in both true and false statements independently [26,47], but the half-truth effect is hypothesized to be evident even in a single presentation of a message. We propose that message structure, or more so the message order, will shape perceived truthfulness of misleading claims even when the message is only viewed once.

Third, the illusory truth effect is mediated by processing fluency [29,48,49] and is found when the repetitions happen over various time intervals [26,27,47,50,51] and with various numbers of repetitions [26,28,50,51]. By contrast, the half-truth effect hypothesizes that credibility is either built or undermined in the initial statement, creating either an acquiescence mindset (when the initial statement is true) or a naysaying mindset (when the initial statement is false), and that initial perception will carry over onto the subsequent elements of the message—even if the latter is of the opposite valence.

Given the prevalence of misinformation on both social media and traditional media, plus the fact that prior knowledge may not always save one from falling prey to misinformation [26,27,52], understanding the various elements that influence believability of a message is extremely important. When considering misinformation in the real world, specifically in the context of sustainability, the effect of message order becomes significantly more important as it lends itself to consumer judgements and decision-making.

4. Sustainability and Misinformation

Misinformation has spread both on- and off-line across many important topics including politics, sustainability, and others. Misinformation is so prevalent on sustainability issues that public belief on the subject (e.g., climate change) does not accurately reflect the consensus among scientists. While the vast majority of climate scientists agree that climate warming is likely to be a result of human activities [53], only about 57% of the public believes the same [54]. Importantly, the general misunderstanding of sustainability topics leads to a (false) belief that adopting sustainable solutions is ineffective or undesirable, resulting in reduced implementation of available solutions, such as sustainable living and GMOs (e.g., genetically modified crops), to the detriment of the environment [55].

This paper investigates how the half-truth effect may contribute to the spreading of false information on sustainable living and GMOs, as well as a potential tactic to highlight the falsehoods when they are present. This is an important avenue of research given the relevant role that sustainable solutions play in benefitting the environment and humankind [55,56]. Research has documented several environmental benefits that results from adopting sustainable practices. For instance, the implementation of sustainable agricultural technologies using GMOs can result in more productive food systems, larger yields, and enhanced food security [56,57,58,59]. Additionally, sustainable living practices such as reducing energy consumption can help reduce carbon footprint and improve air and water quality [60]. At the same time, however, public perceptions of sustainable living have been negatively influenced by misinformation leading to the (false) belief that living sustainably is only possible for high income populations and/or by making lifestyle sacrifices [55], and the (false) belief that food grown from GMO seeds is not safe to eat [61].

Thus, sustainable living practices and GMOs are both solutions that can provide substantial benefits to the environment and society. Improving the understanding and acceptance of these ideas, however, has been undermined by the spreading of false messages. The present work investigates how the half-truth effect influences false beliefs in these topics, as well as how to counter this misinformation by applying the Poison Parasite Counter by Cialdini and colleagues [21].

5. Countering the Half-Truth Effect through Poison Parasite Counter

Given that misinformation has become an issue of growing concern in recent years, research has focused on identifying strategies to combat its proliferation. For example, some research has shown that belief in false information can be reduced through counterarguments and misinformation reminders [62,63]. However, if the debunking strategy is encountered without having first seen the false information, the debunking strategies can result in an increased (relative to the no-correction condition) belief in the misinformation [64]. In fact, repeated exposure to false information enhances its perceived truthfulness, even when the information is followed by corrections [28].

Recently, Cialdini and colleagues [21] have introduced the Poison Parasite Counter (PPC) as a method to durably counter false information. The PPC presents two components, the “poison” and the “parasite”. The “poison” component refers to a counterargument that can effectively offset a false claim. In order to be poisonous enough, the counterargument can, for instance, point to the inaccuracy or dishonesty of the false claim. The “parasitic” component decreases belief in misinformation by embedding a counterargument into a false claim. That is, the parasitic component relies on associative memory by enhancing the perceptual similarity between the counterargument and the original false message, so that when one reencounters the original message, that false message acts as a retrieval cue for the counter-message. By creating an association between the false message and the counter argument, the parasitic component undermines the effects of repeated exposure to false claims. The PPC has been shown to counter misleading messages regarding political candidates [21].

We propose that the PPC can be effectively employed to reduce believability of factually untrue statements, even in the face of the half-truth effect. Additionally, whereas Cialdini and colleagues focused their PPC work on messages that were completely false, we seek to examine the effectiveness of the PPC in undermining belief in misleading messages that are composed by true and false claims that are linked by a flawed logic. That is, even in messages composed of two true elements, if the logical connection between those statements is not sound, then the message is factually untrue in its composite. Thus, the PPC, if effective, should reduce the belief in the composite message made up of factually true statements that are linked by a flawed logical relationship.

Hence, we hypothesize that in the absence of PPC, the half-truth effect will be prominent such that a post that begins with a true statement (regardless of the truth of the second part of the message) will be more likely to be believed than a message that begins with a false statement (even if the second half of the message present true information). However, when the participant is presented with PPC inoculation, the belief in the original post will decrease, but the half-truth effect will remain—the PPC will produce a uniform decrease in the belief of all message structures.

6. Materials and Methods

6.1. Overview

We examine the half-truth effect through two studies. The first study directly tests the role of the half-truth effect in shaping perceived truthfulness of misinformation on sustainability and sustainable living. The study also tests the Poison Parasite Counter (PPC) as a method to reduce belief in factually untrue statements—either because the underlying statements are false or because the stated conclusion does not logically follow from the stated premise. The second study aims to extend the results of the first by testing the moderating role of an individual trait—bullshit receptivity (BSR) [20] on both the half-truth effect and the PPC. Further, the second study uses a new content category—false information regarding genetically modified organisms (GMOs).

In constructing the stimuli for our two experiments, we wanted to control for several elements that have been shown to influence belief in misinformation: prior exposure [28] and political ideology [24]. Previous research studies have often focused on stimuli (e.g., memes or headlines) that had been pulled from a fact-checking site (e.g., https://www.snopes.com/ accessed on 30 March 2022) in order to ensure the validity and reliability of the false information [25,33]. The problem with this approach is that, by definition, the only items that appear on those types of sites are currently circulating in the online environment. Thus, it is impossible to know if the presented stimuli is novel to the participant or if it is influenced by pre-existing beliefs. Further, much of the existing misinformation circulating online is manufactured to be either liberal leaning or conservative leaning. So, when using a currently circulating headline or meme, the reported belief in that stimulus is likely to be asymmetrically influenced by political ideology [24,31].

In order to control for these hazards, we selected individual statements that were factually either true or false. Then, we tested these statements to identify specific statements that were uniformly judged correctly (i.e., either true or false) by participants across the political ideological spectrum. Then, the focal stimuli were created to mix and match true and false statements (counter balancing order) in order to control for content while varying structure. Further, since these combined statements were constructed specifically for this study, no one will have encountered this specific argument prior to the experiment.

6.2. Pretest

In order to identify demonstrably true and false statements that will be the building blocks of our stimuli, we collected statements from online sources (e.g., news articles, web sites, scientific reports, etc.; c.f., [55,65,66]) that confirmed or debunked popular beliefs on topics of sustainability and GMOs. Although we collected statements that were demonstrably true or false on their merits, it was important to demonstrate that the general public perceived the statement to be true or false. In addition, given that political ideology has been shown to impact perception of misinformation [23,24], we used the pre-test to ensure that the statements selected were equally believed (or not) by conservatives and liberals.

The participants (383 undergraduates across two study sessions) reviewed 61 statements that discussed either sustainability or GMOs, and rated each on their perception that the statement was (1) definitely false to (5) definitely true. After reviewing the statements, participants reported their demographic information and their political affiliation through a one-item self-reported measure (“Which option best describes your political ideology?” (1)—Very liberal to (7)—Very conservative [67]). We analyzed the statements to identify false statements that were perceived as false and true statements that were perceived as true among across categories of political identification. The selected statements were chosen because there was no significant difference between the reported truth of the statement for self-described liberals vs. self-described conservatives (all p-values > 0.12). The true statements and false statements were then combined to create a social media post in the form of premise (either true or false), followed by “therefore” and a conclusion that was either true or false. Each statement was included as a premise and a conclusion in different message configurations (see Appendix A for a full list of stimuli used in each study).

7. Experimental Results

7.1. Overview of Experiments

Experiment 1 uses a repeated measures design with one between-subjects variable (true–false order of the statement: True–True, True–False, False–True, False–False) and one within-subjects variable (time one: original statement; time two: Poison Parasite Counter (PPC)) to measure perceived truthfulness of the statement and show the basic half-truth effect.

Experiment 2 also uses a repeated measures design with two between-subjects variables and one within-subjects variable to test moderation of the half-truth effect both before and after the PPC. Specifically, the true–false order of statements tested in experiment 1 is paired with the proposed moderator—the individual difference measure of bullshit receptivity (BSR) [20] as the between-subjects variables. The perceived truthfulness of the statement is measured both before and after the PPC as the within-subjects variable.

7.2. Experiment 1: Participants and Design

Two hundred and eighty-seven MTurk participants (59.2% female; mean age 41.6; age range: 19–76) were recruited in exchange for a nominal fee to participate in a research study to “examine consumer’s perceptions of different pieces of information.” An additional 17 participants started the survey but did not pass the attention checks and were excluded from further analysis. An a priori power analysis using G*Power 3.1 [68] recommends a sample size of 304 for this analytical design and a small effect size. Thus, this sample size is appropriately powered for this analysis.

7.3. Experiment 1: Procedure

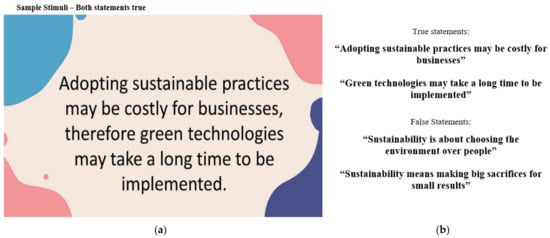

All participants were required to view the survey on a larger screen device and were rejected if they attempted to participate from a mobile phone. After reading and agreeing to the informed consent document, participants were asked to remove headphones to reduce distractions. Then, participants were asked to read and review a “social media post” that was constructed as a two-statement pair (see Figure 2 and Appendix A and Appendix B). The social media post stimuli contained a premise (either true or false), followed by “therefore” and a conclusion that was either true or false. For instance, the social media post stating “Adopting sustainable practices may be costly for businesses, therefore sustainability is about choosing the environment over people” consisted of a true premise linked to a false conclusion (please refer to the Web Appendix A to view all stimuli that were used). All statements were counter-balanced, such that all statements appeared as a premise or conclusion in both mixed-true/false conditions and the conditions where both statements were true or both statements were false. Hence, the counter-balanced version of the previous example was “Sustainability is about choosing the environment over people, therefore adopting sustainable practices may be costly for businesses.” The statements chosen to make up the stimuli were pulled from popular myths and facts related to sustainability and pre-tested to ensure they were generally perceived to be true or false on their own merits and for all participants—those who identify as liberal and those who identify as conservative.

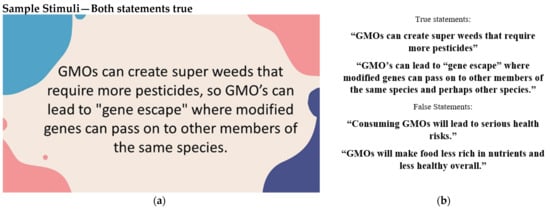

Figure 2.

Experiment 1: Sample “Social Media Posts”. All statements were counterbalanced such that all statements appeared as a premise or conclusion in both mixed-truth conditions, as well as the conditions where both statements are true or both statements are false. (a) Example post with true premise and true conclusion; (b) statements used to construct the social media post stimuli. See Appendix A for a full set of tested stimuli.

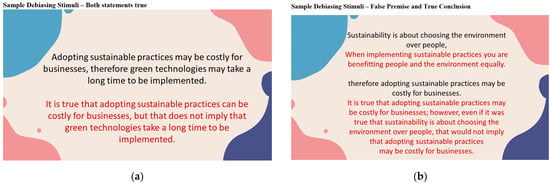

After reviewing the stimuli, participants were asked to rate the social media post on a two-item, seven-point truth scale (“How truthful is the social media post that you just saw?” and “How honest is the social media post that you just saw?”). The two-item scale was reliable (α = 0.95) and was averaged for analysis. Next, the participant was shown the original stimuli with text designed to debias the statement using the poison parasite counter (PPC, [21], see Figure 3). The collection of demographic information (gender, age, ethnicity, education, and political ideology) was used as a filler task. Finally, the participant again reviewed the original “social media post” and rated it on both truthfulness and honesty. These two items were also combined into a two-item scale (α = 0.96) for analysis.

Figure 3.

Experiment 1: Sample De-biasing Sustainability Stimuli. (a) Both premise and conclusion are true and the de-biasing statement is listed in red; (b) premise is false and conclusion is true and the de-biasing statement is listed in red.

7.4. Experiment 1: Results and Discussion

Results were analyzed using a repeated measures ANOVA as a function of the combination of statements in the stimulus (true vs. false). In order to ensure that political ideology (PI) was not influencing the results, the repeated measures ANOVA was run with and without PI included as a covariate. The covariate (PI) was not significant either by itself or in conjunction with any other variable, and the other results were consistent when run with or without the covariate. Therefore, we report the analysis that includes the covariate in order to remove the concern that PI may have impacted the results.

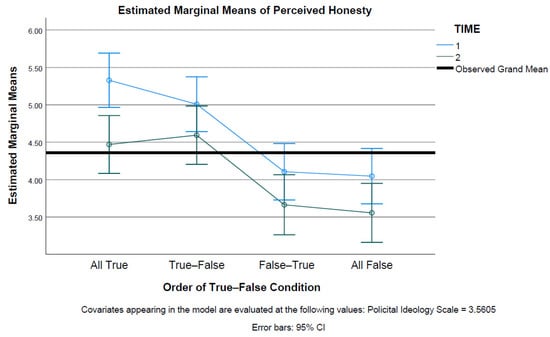

The results of a repeated measures ANOVA with political ideology as a covariate and including planned contrast run within the ANOVA show that the results are consistent with the hypothesized half-truth effect. That is, there is a significant between-subject main effect of the truth–honesty scale (F (1, 282) = 10.43, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.1), and a significant within-subject main effect of time (ratings of the original stimulus vs. the rating after seeing the de-biasing stimuli, F (1, 282) = 18.09, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.06). In addition, the paired comparisons show that the stimuli that start with a true statement (True–True and True–False) are not significantly different from each other at either time 1 or time 2 (Time 1: p = 0.221 n.s.; Time 2: p = 0.657 n.s.). Similarly, the stimuli that start with a false statement (False–True and False–False) are not significantly different from each other at either time 1 or time 2 (Time 1: p = 0.826 n.s.; Time 2: p = 0.285 n.s.). However, in the planned contrasts comparing statements beginning with a true statement to the statements beginning with a false statement, all paired contrasts are significantly different (all p’s < 0.01) (see Table 1 and Figure 4).

Table 1.

Experiment 1: Sustainability Stimuli—premise [therefore …] conclusion. Truth–honesty scale of the original stimuli (time 1) and after viewing the de-biasing stimuli (time 2).

Figure 4.

Experiment 1: Truth–honesty scale by stimuli type at time 1 (Blue line: original stimuli) and time 2 (Green line: original stimuli after de-biasing).

Taken together, these data support our hypothesis and suggest that the perception of the truthfulness of a statement is dependent on the order in which true and false statements are presented. It appears that presenting a true claim first does increase the believability of the entire argument, and presenting a false claim first reduces believability of the message. Hence, the order in which claims of mixed validity are presented appear to be important moderator of the half-truth effect.

In addition, the use of Cialdini’s [21] PPC debiasing technique reduces believability of all claims equally. The half-truth effect is evident both with and without the debiasing technique, albeit at a lower perception of truth for all executions.

Thus, the results suggest that message structure influences perceived truthfulness of false claims. Notably, the results introduce a novel effect that has not been analyzed by previous research. In fact, whereas past work has investigated the effects of repetition on individuals’ belief [26,45,52], the current work examines how the combination of statements, specifically true and false ones, influences perceived truthfulness of misinformation on the first presentation.

Next, we investigate the potential moderator, Pennycook’s BSR (bullshit receptivity) [20]. Our hypotheses suggest that those who report high BSR will be more likely to consider a statement to be true based only on the syntactical elements and, thus, will not exhibit the half-truth effect because they are equally likely to believe both the true and false premise. However, those who are low in BSR will be more likely to experience the half-truth effect because they will actively evaluate the veracity of the premise presented in the stimuli.

Furthermore, we propose a differential effect of the PPC (Poison Parasite Counter, [21]) across the BSR spectrum. For those who base their original perceptions on syntax rather than content (high BSR), the PPC should highlight the truthfulness (or not) of the premise and the half-truth effect should become evident. For those that are already focusing on content (low BSR), the PPC should simply reduce the perceptions of truthfulness—that is, the pattern should replicate the results of experiment 1—because the PPC will highlight the logical fallacy linking the premise and the conclusion (e.g., using the connector “therefore” or “leads to” when the two statements are unrelated). More simply, our hypothesis is that high BSR individuals will adjust their beliefs because the additional Information will call into question the validity of the false statements, but their truthfulness assessment will be anchored on the premise. Conversely, the initial half-truth pattern will remain for low BSR individuals, but the perceived truthfulness of each of the paired statements will be diminished to account for the lack of causal relation between the two pieces of information.

Thus, our second study seeks to replicate the half-truth effect found in the first study, but only in the case of low BSR individuals. Additionally, we will be testing our predictions utilizing statements about GMOs as this domain is often fraught with misinformation and partial truths.

7.5. Experiment 2: Participants and Design

Four hundred and twenty-five mTurk participants (48.7% female; mean age 41.2; age range: 19–80) were recruited in exchange for a nominal fee to participate in a research study to “examine consumer’s perceptions of different pieces of information.” An additional 21 participants started the survey but did not pass the attention checks and were excluded from further analysis. The study design from Experiment 1 was replicated with the inclusion of BSR as a moderator of the half-truth effect. An a priori power analysis using G*Power 3.1 [68] recommends a sample size of 435 for this analytical design and a small effect size. Thus, this sample size is sufficiently powered for this analysis.

7.6. Experiment 2: Procedure

The procedure for Experiment 2 was the same as that for Experiment 1, except the true and false statements were pulled from GMO facts and myths (e.g., “GMOs can create super weeds that require more pesticides”, “Consuming GMOs will lead to serious health risks”) and participants completed the BSR scale [20] (example items “Hidden meaning transforms unparalleled abstract beauty”, “Good health imparts reality to subtle creativity”) as a potential moderator to the half-truth effect. Figure 5 provides a sample stimulus and the individual statements (See Appendix B for all survey questions). All stimuli that were used are available in the Appendix A. As in the first experiment, the participants were required to participate on a larger screen (i.e., not a mobile device), and first responded to the assigned “social media post” rating it on truthfulness and honesty. Then, participants viewed the same message with a debiasing annotation [21], followed by the demographics questions and the BSR scale. Finally, the participants rated the original “social media post” a second time. At both time 1 and time 2, the truth and honesty scales were averaged for the analysis (Time 1: α = 0.96, Time 2: α = 0.97).

Figure 5.

Experiment 2: Sample “Social Media Posts”. All statements were counter-balanced such that all statements appeared as a premise or conclusion in both mixed-truth conditions, as well as the conditions where both statements are true or both statements are false. (a) Example post with true premise and true conclusion; (b) statements used to construct the social media post stimuli. See Appendix A for a full set of tested stimuli.

7.7. Experiment 2: Results

First, data from the evaluation of the original presentation of the stimulus (Time 1) were evaluated for moderation using the PROCESS version 4.0 [69] Model 1 with 5000 bootstrap samples for bias corrected 95% confidence intervals. The order of statement presentation (True–True, True–False, False–True, and False–False) served as the categorical dependent variable (X), BSR scale was the continuous moderation variable (W), the two-item truth–honesty scale was the independent variable (Y), and political ideology (PI) was included as a covariate (see Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Experiment 2: Moderation analysis (covariate: political ideology).

Because PROCESS is based on a regression model, the categorical dependent variable was dummy coded into three variables to represent the four conditions. The results show that the overall model is significant (p < 0.001). There is a main effect of the moderator, BSR (p = 0.02), and there is a main effect of the order of presentation that is consistent with the half-truth effect (replicating Experiment 1).

That is, the two conditions where a true statement is presented first (True–True and True–False) are not significantly different (p = 0.4, ns), but both conditions where the false statement is presented first (False–True and False–False) are significantly different from the True–True condition (p < 0.001 and p = 0.03, respectively). In addition, BSR and statement-order interact (X × W) such that at low levels of BSR (1.4), the conditional means are significantly different (p = 0.001) in a pattern that show the half-truth effect (see Table 2). Conversely, at moderate BSR (2.6) and at high BSR (3.5), the test for equality of conditional means shows no significant difference (p = 0.16 and p = 0.77, respectively). Thus, the half-truth effect is evident for low BSR participants, but not for moderate or high BSR participants when evaluating the original stimuli.

Table 2.

Experiment 2: GMO Stimuli—premise [therefore …] conclusion—by BSR (low, medium, high) with political ideology (PI) included as a covariate. Truth–honesty scale of the original stimuli (time 1) and after viewing the de-biasing stimuli (time 2).

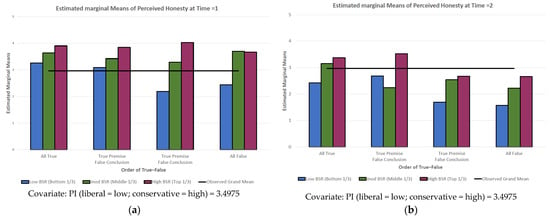

In order to evaluate the influence of the debiasing technique [21], a repeated measures ANOVA was run with BSR categorized as low (<1.4), medium (1.4 < 3.5), and high (>3.5), as suggested by the PROCESS model. Political ideology was also included as a covariate.

The results of the repeated measures ANOVA show a significant difference between the first rating and the second (i.e., a main effect of time, p < 0.001), an interaction of time and statement order (p = 0.02), and a three-way interaction of time × statement order × BSR (p = 0.01). These results show that the debiasing technique [21] has a different effect at the various levels of BSR. That is, at Time 1, only low BSR show the half-truth effect, and moderate to high BSR show no difference in perceived truth across the various statement truth/false order (p > 0.6). Following debiasing stimulus, all three levels of BSR show a significant difference in perceived truthfulness across the various statement truth/false order (p < 0.03).

For the low BSR individuals, the half-truth effect is evident for both the initial stimulus (Time 1) and after de-biasing (Time 2), albeit lower perceived validity. That is, all conditions were equally affected: the paired comparisons show that the stimuli that start with a true statement (True–True and True–False) are not significantly different from each other at either Time 1 or Time 2 (Time 1: p = 0.6 n.s.; Time 2: p = 0.5 n.s.). Similarly, the stimuli that start with a false statement (False–True and False–False) are not significantly different from each other at either Time 1 or Time 2 (Time 1: p = 0.5 n.s.; Time 2: p = 0.7 n.s.). However, regarding the planned contrasts that compare statements beginning with a true statement to the statements beginning with a false statement, all paired contrasts were significantly different at both Time 1 and Time 2 (all p’s < 0.04, see Table 2). This pattern of results is consistent with the half-truth effect at both Time 1 and Time 2.

For moderate BSR individuals, all statements are perceived to be equally true at Time 1 (p = 0.6, ns), but after debiasing (Time 2), the statements that contains two true statements are perceived to be significantly more true than the True–False stimulus (p = 0.03), the False–False stimulus (p = 0.01), and (marginally) the False–True stimulus (p = 0.09). This suggest that the de-biasing works best for those with a moderate level of BSR.

For high BSR individuals, all statements are perceived to be equally true at Time 1 (p = 0.8, ns), but after debiasing (Time 2), the half-truth effect is evident. That is, the paired comparisons show that the stimuli that start with a true statement (True–True and True–False) are not significantly different from each other at time 2 (p = 0.6, n.s.). Similarly, the stimuli that start with a false statement (False–True and False–False) are not significantly different from each other at Time 2 (p = 0.9, n.s.). However, the planned contrasts comparing statements beginning with a true statement to the statements beginning with a false statement, all paired contrasts are significantly different at Time 2 (all p’s < 0.04, see Table 2 and Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Experiment 2: Results of the repeated measures ANOVA Evaluation of truthfulness of stimuli by BSR (low, medium, high) with political ideology (PI) as a covariate; (a) original stimuli after the first presentation (Time 1); (b) evaluating the original stimuli after de-biasing (Time 2).

The results from our second experiment provide insight into the moderating role of BSR for the half-truth effect. Although the BSR does not moderate the illusory truth effect [35], it does have a strong moderating influence on the half-truth effect. That is, as scores on the BSR decrease, people are more susceptible to the half-truth effect. However, when the Poison Parasite Counter technique is used [21], skepticism increases for all claims for all individuals. Thus, the results of the present study improve understanding of how individual cognitive traits shape belief in misinformation.

8. Discussion

“That a lie which is half a truth is ever the blackest of lies,That a lie which is all a lie may be met and fought with outright,But a lie which is part a truth is a harder matter to fight.”[1] (St. 8).

The results of two experiments show that Tennyson’s observations concerning the existence of the half-truth effect are correct, but order of the true and false elements matter. Presenting a true claim first encourages message recipients to perceive the communicator credible and trustworthy [37,38,39]. These perceptions then increase the perceived validity of subsequent claims made by the communicator. Moreover, receiving a true claim first should increases acquiescence mindset that encourages recipients to carry over that mindset to infer subsequent claims are also valid [40,41]. However, presenting a false claim first decreases perceptions of source credibility and trustworthiness, and produces a naysaying mindset on the part of message recipients, resulting in a perception that the entire message is false.

Our results show that the half-truth effect enhances belief in misinformation regarding sustainability and GMOs. Specifically, the studies indicate that the order in which true and false facts are presented influences the perception of the truthfulness of the combined claim. That is, presenting a true claim first increases believability of the overall argument, whereas presenting a false claim first reduces believability. The results also indicate that the half-truth effect is moderated by individuals’ bullshit receptivity (BSR, [20]), such that the effect is evident for individuals with low BSR, but not for individuals with moderate or high BSR. Additionally, the studies show that using the Poison Parasite Counter (PPC) debiasing technique [21] reduces belief in false information but does not eliminate the half-truth effect. In fact, for high BSR individuals, the PPC appears to move the participant from wholesale belief to the half-truth effect. Overall, the results suggest that message structure influences perceived truthfulness of misinformation. Importantly, the results introduce a novel effect that has not been investigated by previous research. In fact, whereas past work has investigated the effects of repetition on individuals’ belief [26,35,45,52], the present research examines multiple statements in tandem comprised of mixed veracity (i.e., true and false) to understand the impact on perceived believability of false information.

9. Theoretical and Practical Implications, Limitations, and Future Research

The current work makes several contributions to both theory and practice. First, theoretically, this paper expands on the current literature on misinformation by introducing and testing the half-truth effect. Although half-truths have been discussed in politics since the 1960s [70], this research shows how the structure and order of the true and false components of a false message impacts its perceived truthfulness. Previous research on misinformation has focused on the content of false messages [24,31,71]. Yet, the persuasiveness of information is also shaped by the order in which it is received [72,73]. We advance the misinformation literature by showing the impact of the claims’ structure, content, and presentation order on believability of false or partially false information.

Additionally, the practical implications of this research can be employed by psychologists, public policy professionals and communications experts to formulate primary communications, as well as initiate a response to false claims being pushed on social media and elsewhere. Public perceptions of sustainability topics such as sustainable living and GMOs are fraught with misinformation. Common misconceptions view sustainable living as a practice that is only possible for high income populations and requires making lifestyle sacrifices plus adherence to strict rules [55]. Similarly, false claims on the safety of GMOs are negatively influencing individuals’ perceptions of the food source, despite the fact that scientific evidence reports no significant hazard connected to the use of genetically modified crops [59,74,75]. The present research provides a roadmap to dissect the source of the misconceptions and construct a response that is likely to undermine the belief in the false narrative in favor of factually true information. For example, by knowing that a true statement followed by a false statement will increase the belief in the false statement, policy makers will be better equipped to construct a response to misinformation that starts with a reference to what is false rather than a reference to what is true.

In addition, by knowing that individuals who are prone to perceive meaningless claims as profound (high BSR) are likely to believe false information regardless of the order of delivery, the response to the false narratives circulating online could be to construct a response that attacks the narrative as a whole. However, for those who are low on the BSR scale, the best response to counter misinformation is to address the elements of the message using the Cialdini and colleagues’ [21] PPC method. Our work shows communicators how to adapt the PPC to reduce belief in misinformation regarding scientific topics that are flawed in logic and/or factual content for all individuals regardless of the propensity to perceive meaningless claims as profound (BSR).

It is important to note that the observed pattern of results was found even though some of the claims were blatantly false, none of the claims were logically related, and people believe that they are not susceptible to misinformation but that others are susceptible [76]. By understanding the differences in belief outcomes among people who find meaning in meaningless claims (high BSR) and those who are more attuned to the content of the message (low BSR), communicators and public policy experts can be better equipped to attenuate these misperceptions with the Poison Parasite Counter technique and by formulating a response that begins with a reference to the false information.

As with all research projects, some limitations are present in order to design and control the experiments. We chose sustainability and GMO facts as the context for the stimuli; however, misinformation is prevalent in many more contexts. Future research should examine the extent to which our results generalize to other stimuli, contexts, and individuals. In addition, our studies look at the moderating variables of message structure (order of presentation) and an individual difference (BSR). Based on prior research, we hypothesize, but do not test, that the half-truth effect is mediated by perceptions of credibility, trustworthiness, open-mindedness, and an acquiescence mindset created by the premise of the presented argument. Future research should investigate these potential mediating variables, as well as other potential moderating variables that might impact the half-truth effect.

10. Conclusions

In conclusion, it appears that Tennyson is, in fact, correct—half a truth is ever the blackest of lies—but only when the premise of the argument is true. Even when an argument is logically flawed, a true premise can increase source credibility and carry over to subsequent claims. However, it appears that, using the Poison Parasite Counter technique, even a “lie which is part a truth” can, in fact, be “fought” or debiased. That is, although the half-truth effect is not eliminated, the Poison Parasite Counter technique reduces the initial perception of truthfulness across the board for both mixed-truth messages and those that are “all a lie.”

Author Contributions

All authors (A.B., E.N., S.P.M. and F.R.K.) contributed equally to conceptualization, methodology, analysis, data curation, and writing; F.R.K. and S.P.M. supervised all stages of the project. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Lindner College of Business 2021 Lindner Summer Research Grant and funds from the Donald E. Weston Chair.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of University of Cincinnati (protocol code 2021-0230 and date of approval: 16 March 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available at the following link https://osf.io/uh72m/?view_only=34d25957ecb047ffb917616caef001e0 (accessed on 30 March 2022).

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the Lindner College of Business and the Donald E. Weston Chair, held by Frank R. Kardes, for support on this project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

All stimuli are included in the web appendix found at the following link: https://osf.io/uh72m/?view_only=34d25957ecb047ffb917616caef001e0 (accessed on 30 March 2022).

Appendix B

The questions from the survey are included in the web appendix found at the following link: https://osf.io/uh72m/?view_only=34d25957ecb047ffb917616caef001e0 (accessed on 30 March 2022).

References

- Tennyson, L.A. The Grandmother. 1864. Available online: https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O198447/the-grandmother-photograph-cameron-julia-margaret/ (accessed on 30 March 2022).

- Lewandowsky, S. Climate Change Disinformation and how to Combat It. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2021, 42, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treen, K.M.d.; Williams, H.T.P.; O’Neill, S.J. Online Misinformation about Climate Change. Wiley interdisciplinary reviews. Clim. Change 2020, 11, e665. [Google Scholar]

- Vicario, M.D.; Bessi, A.; Zollo, F.; Petroni, F.; Scala, A.; Caldarelli, G.; Stanley, H.E.; Quattrociocchi, W. The Spreading of Misinformation Online. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 554–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, Y.; McKee, M.; Torbica, A.; Stuckler, D. Systematic Literature Review on the Spread of Health-Related Misinformation on Social Media. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 240, 112552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthel, M.; Mitchell, A.; Holcomb, J. Many Americans Believe Fake News Is Sowing Confusion. 2016. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/2016/12/15/many-americans-believe-fake-news-is-sowing-confusion/ (accessed on 30 March 2022).

- Vosoughi, S.; Roy, D.; Aral, S. The Spread of True and False News Online. Sci. (Am. Assoc. Adv. Sci.) 2018, 359, 1146–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.C. Presumed Effects of “Fake News” on the Global Warming Discussion in a Cross-Cultural Context. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, S.; Kim, S. The Crisis of Public Health and Infodemic: Analyzing Belief Structure of Fake News about COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ries, M. The COVID-19 Infodemic: Mechanism, Impact, and Counter-Measures—A Review of Reviews. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheufele, D.A.; Krause, N.M. Science Audiences, Misinformation, and Fake News. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 7662–7669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Sousa, Á.F.L.; Schneider, G.; de Carvalho, H.E.F.; de Oliveira, L.B.; Lima, S.V.M.A.; de Sousa, A.R.; de Araújo, T.M.E.; Camargo, E.L.S.; Oriá, M.O.B.; Ramos, C.V.; et al. COVID-19 Misinformation in Portuguese-Speaking Countries: Agreement with Content and Associated Factors. Sustainability 2021, 14, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, J.; McConnell, K.; Brulle, R. Evidence-Based Strategies to Combat Scientific Misinformation. Nat. Clim. Change 2019, 9, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, H.J. The Biggest Pandemic Risk? Viral Misinformation. Nature 2018, 562, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Loomba, S.; de Figueiredo, A.; Piatek, S.J.; de Graaf, K.; Larson, H.J. Measuring the Impact of COVID-19 Vaccine Misinformation on Vaccination Intent in the UK and USA. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2021, 5, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Linden, S.; Maibach, E.; Cook, J.; Leiserowitz, A.; Lewandowsky, S. Inoculating Against Misinformation. Sci. (Am. Assoc. Adv. Sci.) 2017, 358, 1141–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacciatore, M.A. Misinformation and Public Opinion of Science and Health: Approaches, Findings, and Future Directions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlton, E. Fake News: What It Is, and How to Spot It. 2019. Available online: https://europeansting.com/2019/03/06/fake-news-what-it-is-and-how-to-spot-it/ (accessed on 30 March 2022).

- Merriam-Webster. Half-Truth. In Merriam-Webster.Com Dictionary. 2022. Available online: https://www-merriam-webster-com.uc.idm.oclc.org/dictionary/half-truth (accessed on 30 March 2022).

- Pennycook, G.; Cheyne, J.A.; Barr, N.; Koehler, D.J.; Fugelsang, J.A. On the Reception and Detection of Pseudo-Profound Bullshit. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2015, 10, 549–563. [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Lasky-Fink, J.; Demaine, L.J.; Barrett, D.W.; Sagarin, B.J.; Rogers, T. Poison Parasite Counter: Turning Duplicitous Mass Communications into Self-Negating Memory-Retrieval Cues. Psychol. Sci. 2021, 32, 1811–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xarhoulacos, C.; Anagnostopoulou, A.; Stergiopoulos, G.; Gritzalis, D. Misinformation Vs. Situational Awareness: The Art of Deception and the Need for Cross-Domain Detection. Sensors 2021, 21, 5496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bavel, J.J.; Pereira, A. The Partisan Brain: An Identity-Based Model of Political Belief. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2018, 22, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pereira, A.; Harris, E.; Van Bavel, J.J. Identity Concerns Drive Belief: The Impact of Partisan Identity on the Belief and Dissemination of True and False News. Group Processes Intergroup Relat. 2021, 136843022110300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennycook, G.; Rand, D.G. Lazy, Not Biased: Susceptibility to Partisan Fake News is Better Explained by Lack of Reasoning than by Motivated Reasoning. Cognition 2019, 188, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazio, L.K.; Pillai, R.M.; Patel, D. The Effects of Repetition on Belief in Naturalistic Settings. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazio, L.K. Repetition Increases Perceived Truth Even for Known Falsehoods. Collabra. Psychol. 2020, 6, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennycook, G.; Cannon, T.D.; Rand, D.G. Prior Exposure Increases Perceived Accuracy of Fake News. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2018, 147, 1865–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begg, I.M.; Anas, A.; Farinacci, S. Dissociation of Processes in Belief: Source Recollection, Statement Familiarity, and the Illusion of Truth. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 1992, 121, 446–458. [Google Scholar]

- Unkelbach, C. Reversing the Truth Effect: Learning the Interpretation of Processing Fluency in Judgments of Truth. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 2007, 33, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, C.; Dunning, D. Cognitive and Emotional Correlates of Belief in Political Misinformation: Who Endorses Partisan Misbeliefs? Emotion 2021, 21, 1091–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennycook, G.; Rand, D.G. Who Falls for Fake News? the Roles of Bullshit Receptivity, Overclaiming, Familiarity, and Analytic Thinking. J. Pers. 2020, 88, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronstein, M.V.; Pennycook, G.; Bear, A.; Rand, D.G.; Cannon, T.D. Belief in Fake News is Associated with Delusionality, Dogmatism, Religious Fundamentalism, and Reduced Analytic Thinking. J. Appl. Res. Mem. Cogn. 2019, 8, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gligorić, V.; Moreira da Silva, M.; Eker, S.; van Hoek, N.; Nieuwenhuijzen, E.; Popova, U.; Zeighami, G. The Usual Suspects: How Psychological Motives and Thinking Styles Predict the Endorsement of Well-Known and COVID-19 Conspiracy Beliefs. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 2021, 35, 1171–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De keersmaecker, J.; Dunning, D.; Pennycook, G.; Rand, D.G.; Sanchez, C.; Unkelbach, C.; Roets, A. Investigating the Robustness of the Illusory Truth Effect Across Individual Differences in Cognitive Ability, Need for Cognitive Closure, and Cognitive Style. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2020, 46, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerner, J.S.; Small, D.A.; Loewenstein, G. Heart Strings and Purse Strings: Carryover Effects of Emotions on Economic Decisions. Psychol. Sci. 2004, 15, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruglanski, A.W.; Shah, J.Y.; Pierro, A.; Mannetti, L. When Similarity Breeds Content: Need for Closure and the Allure of Homogeneous and Self-Resembling Groups. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 83, 648–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priester, J.R.; Petty, R.E. Source Attributions and Persuasion: Perceived Honesty as a Determinant of Message Scrutiny. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 21, 637–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priester, J.R.; Petty, R.E. The Influence of Spokesperson Trustworthiness on Message Elaboration, Attitude Strength, and Advertising Effectiveness. J. Consum. Psychol. 2003, 13, 408–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruglanski, A.W.; Webster, D.M. Motivated Closing of the Mind: “Seizing” and “Freezing”. Psychol. Rev. 1996, 103, 263–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roets, A.; Kruglanski, A.W.; Kossowska, M.; Pierro, A.; Hong, Y. The Motivated Gatekeeper of our Minds: New Directions in Need for Closure Theory and Research. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Elsevier Science & Technology: Waltham MA, USA, 2015; Volume 52, pp. 221–283. [Google Scholar]

- Wyer, R.S.; Xu, A.J.; Shen, H. The Effects of Past Behavior on Future Goal-Directed Activity. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Elsevier Science & Technology: Waltham, MA, USA, 2012; Volume 46, pp. 237–283. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, A.J.; Wyer, R.S. The Role of Bolstering and Counterarguing Mind-Sets in Persuasion. J. Consum. Res. 2012, 38, 920–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berg, J.; Dickhaut, J.; McCabe, K. Trust, Reciprocity, and Social History. Games Econ. Behav. 1995, 10, 122–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dechêne, A.; Stahl, C.; Hansen, J.; Wänke, M. The Truth about the Truth: A Meta-Analytic Review of the Truth Effect. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 14, 238–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasher, L.; Goldstein, D.; Toppino, T. Frequency and the Conference of Referential Validity. J. Verbal Learn. Verbal Behav. 1977, 16, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.S.; Nix, L.A. Turning Lies into Truths: Referential Validation of Falsehoods. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 1996, 22, 1088–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reber, R.; Schwarz, N. Effects of Perceptual Fluency on Judgments of Truth. Conscious. Cogn. 1999, 8, 338–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alter, A.L.; Oppenheimer, D.M. Uniting the Tribes of Fluency to Form a Metacognitive Nation. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2009, 13, 219–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.; Barber, S.J. The Effects of Repetition Frequency on the Illusory Truth Effect. Cogn. Res. Princ. Implic. 2021, 6, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigerenzer, G. External Validity of Laboratory Experiments: The Frequency-Validity Relationship. Am. J. Psychol. 1984, 97, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazio, L.K.; Brashier, N.M.; Payne, B.K.; Marsh, E.J. Knowledge does Not Protect Against Illusory Truth. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2015, 144, 993–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, J.; Oreskes, N.; Doran, P.T.; Anderegg, W.R.L.; Verheggen, B.; Maibach, E.W.; Carlton, J.S.; Lewandowsky, S.; Skuce, A.G.; Green, S.A.; et al. Consensus on Consensus: A Synthesis of Consensus Estimates on Human-Caused Global Warming. Environ. Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 48002–48008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marlon, J.; Neyens, L.; Jefferson, M.; Howe, P.; Mildenberger, M.; Leiserowitz, A. Yale Climate Opinion Maps 2021. 2022. Available online: https://climatecommunication.yale.edu/visualizations-data/ycom-us/ (accessed on 30 March 2022).

- Butters, C. Myths and Issues about Sustainable Living. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñeiro, V.; Arias, J.; Dürr, J.; Elverdin, P.; Ibáñez, A.M.; Kinengyere, A.; Opazo, C.M.; Owoo, N.; Page, J.R.; Prager, S.D. A Scoping Review on Incentives for Adoption of Sustainable Agricultural Practices and their Outcomes. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 3, 809–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teklewold, H.; Kassie, M.; Shiferaw, B. Adoption of Multiple Sustainable Agricultural Practices in Rural Ethiopia. J. Agric. Econ. 2013, 64, 597–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannion, A.M.; Morse, S. Biotechnology in Agriculture: Agronomic and Environmental Considerations and Reflections Based on 15 Years of GM Crops. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 2012, 36, 747–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zilberman, D.; Holland, T.G.; Trilnick, I. Agricultural GMOs-what we Know and Where Scientists Disagree. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kamal, A.; Al-Ghamdi, S.G.; Koc, M. Revaluing the Costs and Benefits of Energy Efficiency: A Systematic Review. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 54, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Center. Genetically Modified Foods (GMOs) and Views on Food Safety; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ecker, U.K.H.; Lewandowsky, S.; Jayawardana, K.; Mladenovic, A. Refutations of Equivocal Claims: No Evidence for an Ironic Effect of Counterargument Number. J. Appl. Res. Mem. Cogn. 2019, 8, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahlheim, C.N.; Alexander, T.R.; Peske, C.D. Reminders of Everyday Misinformation Statements can Enhance Memory for and Beliefs in Corrections of those Statements in the Short Term. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 31, 1325–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autry, K.S.; Duarte, S.E. Correcting the Unknown: Negated Corrections may Increase Belief in Misinformation. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 2021, 35, 960–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berezow, A. The Pervasive Myth that GMOs Pose a Threat. 2013. Available online: https://www.usnews.com/debate-club/should-consumers-be-worried-about-genetically-modified-food/the-pervasive-myth-that-gmos-pose-a-threat (accessed on 30 March 2022).

- Alliance for Science. 10 Myths about GMOs. 2015. Available online: https://allianceforscience.cornell.edu/10-myths-about-gmos/ (accessed on 30 March 2022).

- Clarkson, J.J.; Chambers, J.R.; Hirt, E.R.; Otto, A.S.; Kardes, F.R.; Leone, C. The Self-Control Consequences of Political Ideology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 8250–8253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A. Statistical Power Analyses using GPower 3.1: Tests for Correlation and Regression Analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Safire, W. The New Language of Politics: An Anecdotal Dictionary of Catchwords, Slogans, and Political Usage; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1968; pp. xvi+528. [Google Scholar]

- Stekelenburg, A.V.; Schaap, G.J.; Veling, H.P.; Buijzen, M.A. Boosting Understanding and Identification of Scientific Consensus can Help to Correct False Beliefs. Psychol. Sci. 2021, 32, 1549–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haugtvedt, C.P.; Wegener, D.T. Message Order Effects in Persuasion: An Attitude Strength Perspective. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 21, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tormala, Z.L.; Clarkson, J.J. Assimilation and Contrast in Persuasion: The Effects of Source Credibility in Multiple Message Situations. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2007, 33, 559–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolia, A.; Manzo, A.; Veronesi, F.; Rosellini, D. An Overview of the Last 10 Years of Genetically Engineered Crop Safety Research. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2014, 34, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waeber, P.O.; Stoudmann, N.; Langston, J.D.; Ghazoul, J.; Wilmé, L.; Sayer, J.; Nobre, C.; Innes, J.L.; Fernbach, P.; Sloman, S.A.; et al. Choices we make in Times of Crisis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pronin, E.; Gilovich, T.; Ross, L. Objectivity in the Eye of the Beholder: Divergent Perceptions of Bias in Self Versus Others. Psychol. Rev. 2004, 111, 781–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).