Sport for Development Programs Contributing to Sustainable Development Goal 5: A Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Research Aim

1.2. The Outcome Indicators in Gender Equality and Women Empowerment

2. SFD Theories and Frameworks

Literature Review

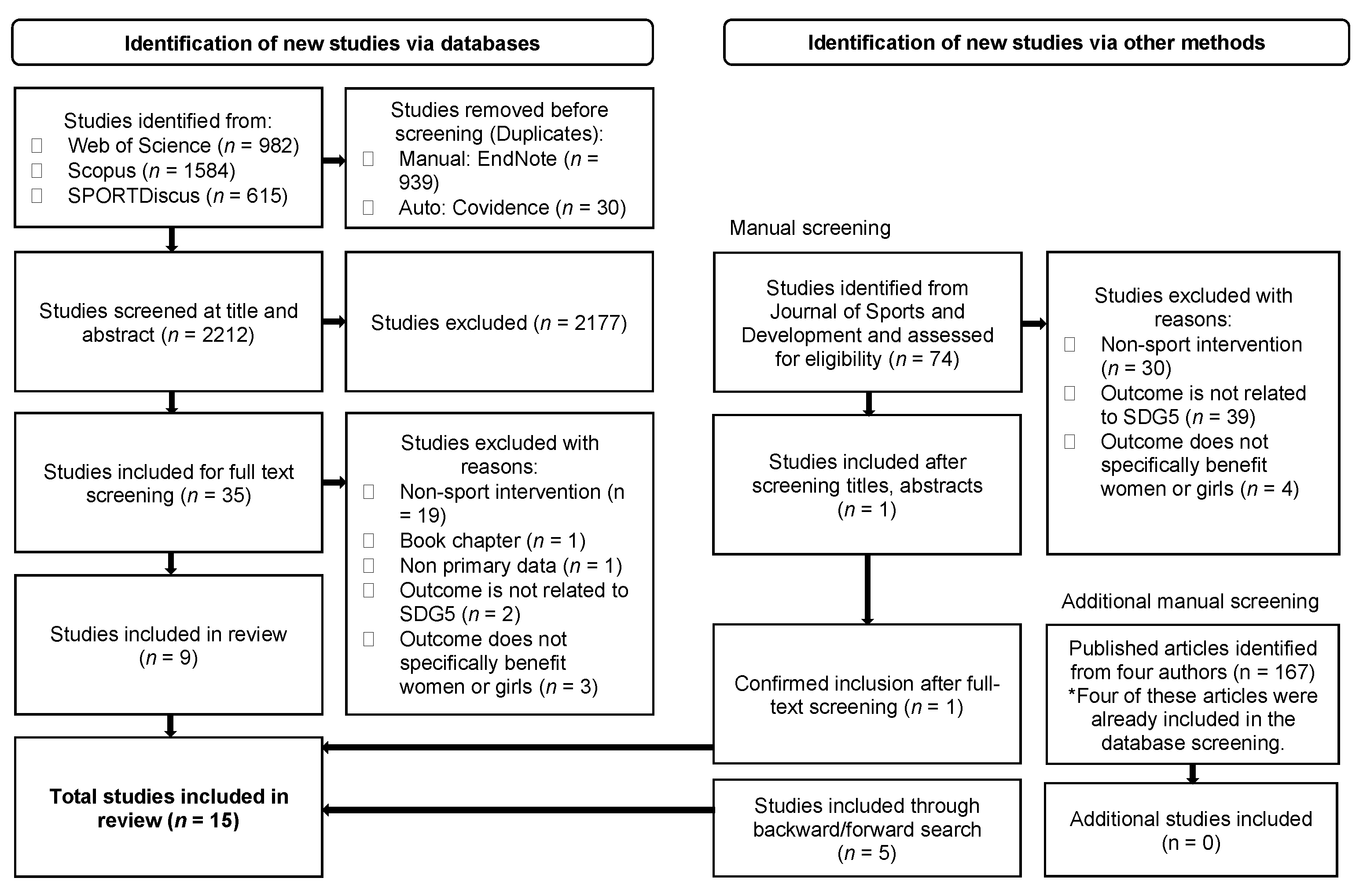

3. Methods

3.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

3.2. Electronic Search

3.3. Screening

3.4. Data Extraction and Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Study Characteristics

4.2. Program Characteristics

4.3. Program Outcomes

5. Discussion

5.1. Reporting of Outcomes through Process and Context

5.2. Research Design

6. Implications for Evaluation and Management of SFD Programs

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Darnell, S.C.; Whitley, M.A.; Camiré, M.; Massey, W.V.; Blom, L.C.; Chawansky, M.; Forde, S.; Hayden, L. Systematic Reviews of Sport for Development Literature: Managerial and Policy Implications. J. Glob. Sport Manag. 2019, 7, 249–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulenkorf, N.; Sherry, E.; Rowe, K. Sport for development: An integrated literature review. J. Sport Manag. 2016, 30, 22–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spaaij, R.; Schulenkorf, N.; Jeanes, R.; Oxford, S. Participatory research in sport-for-development: Complexities, experiences and (missed) opportunities. Sport Manag. Rev. 2018, 21, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kabeer, N. Resources, agency, achievements: Reflections on the measurement of women’s empowerment. Dev. Chang. 1999, 30, 435–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asada, Y.; Hurley, J.; Norheim, O.F.; Johri, M. A three-stage approach to measuring health inequalities and inequities. Int. J. Equity Health 2014, 13, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kawachi, I. A glossary for health inequalities. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2002, 56, 647–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Soysa, L.; Zipp, S. Gender equality, sport and the United Nation‘s system. A historical overview of the slow pace of progress. Sport Soc. 2019, 22, 1783–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherry, E.; Schulenkorf, N.; Seal, E.; Nicholson, M.; Hoye, R. Sport-for-development in the South Pacific region: Macro-, meso-, and micro-perspectives. Sociol. Sport J. 2017, 34, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayhurst, L.M.C. Girls as the ‘New’ Agents of Social Change? Exploring the ‘Girl Effect’ through Sport, Gender and Development Programs in Uganda. Sociol. Res. Online 2013, 18, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hayhurst, L.M.C. Corporatising Sport, Gender and Development: Postcolonial IR feminisms, transnational private governance and global corporate social engagement. Third World Q. 2011, 32, 531–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawansky, M.; Hayhurst, L.M.C. Girls, international development and the politics of sport: Introduction. Sport Soc. 2015, 18, 877–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorpe, H.; Hayhurst, L.; Chawansky, M. ‘Once my relatives see me on social media… it will be something very bad for my family’: The Ethics and Risks of Organizational Representations of Sporting Girls from the Global South. Sociol. Sport J. 2018, 35, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McDonald, M.G. Imagining neoliberal feminisms? Thinking critically about the US diplomacy campaign, ‘Empowering Women and Girls Through Sports’. Sport Soc. 2015, 18, 909–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickel, J. The ‘girl effect’: Liberalism, empowerment and the contradictions of development. Third World Q. 2014, 35, 1355–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnell, S.C.; Hayhurst, L.M. De-colonising the politics and practice of sport-for-development: Critical insights from post-colonial feminist theory and methods. In Global Sport-for-Development; Springer: London, UK, 2013; pp. 33–61. [Google Scholar]

- Coalter, F. Sport for Development: What Game Are We Playing? Routledge: Oxford, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Coalter, F. The politics of sport-for-development: Limited focus programmes and broad gauge problems? Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2010, 45, 295–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coalter, F. ‘There is loads of relationships here’: Developing a programme theory for sport-for-change programmes. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2013, 48, 594–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitley, M.A.; Massey, W.V.; Camiré, M.; Blom, L.C.; Chawansky, M.; Forde, S.; Boutet, M.; Borbee, A.; Darnell, S.C. A systematic review of sport for development interventions across six global cities. Sport Manag. Rev. 2019, 22, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCrom, C.W.; Martin, T. Sport for Development’s Impact on Cultural Adaptability: A Process and Outcome-Based Analysis. J. Sport Manag. 2019, 33, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyras, A.; Welty Peachey, J. Integrating sport-for-development theory and praxis. Sport Manag. Rev. 2011, 14, 311–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, D. Empowering Girls and Women through Physical Education and Sport—Advocacy Brief; UNESCO Asia and Pacific Regional Bureau for Education: Bangkok, Thailand, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, M.K. Gender and women empowerment approaches: Interventions through PRIs and CSOs in Northern India. Womens Stud. Int. Forum 2018, 71, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Development Programme. UNDP Gender Equality Strategy 2014–2017; United Nations Development Programme: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. FAO Policy on Gender Equality; Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dudfield, O.; Dingwall-Smith, M. Sport for Development and Peace and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; The Commonwealth: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, E.M. Gender and the Sustainable Development Goals. Glob. Soc. Policy 2017, 17, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Goal 3: Promote Gender Equality and Empower Wowen. Available online: https://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/gender.shtml (accessed on 17 August 2021).

- United Nations. Goal 5: Achieve Gender Equality and Empower All Women and Girls. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal5 (accessed on 17 August 2021).

- United Nations. Report of the Inter-Agency and Expert Group on Sustainable Development Goal Indicators. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/11803Official-List-of-Proposed-SDG-Indicators.pdf (accessed on 17 August 2021).

- Müller-Wirth, P. Strengthening the Global Framework for Leveraging Sport for Development and Peace, UNDESA, Expert Group Meeting & Integragency Dialogue; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNDESA): New York, NY, USA, 2018; p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Secretariat of United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organisation. Kazan Action Plan. In Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference of Ministers and Senior Officials Responsible for Physical Education and Sport, Kazan, Russian, 14–15 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Forde, S.D. Fear and loathing in Lesotho: An autoethnographic analysis of sport for development and peace. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2015, 50, 958–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, D.; Kwauk, C. Sport and development: An overview, critique, and reconstruction. J. Sport Soc. Issues 2011, 35, 284–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayhurst, L.M.; Szto, C. Corporatizating Activism through Sport-Focused Social Justice? Investigating Nike’s Corporate Responsibility Initiatives in Sport for Development and Peace. J. Sport Soc. Issues 2016, 40, 522–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorpe, H.; Chawansky, M. The ‘girl effect’in action sports for development: The case of the female practitioners of Skateistan. In Women in Action Sport Cultures; Springer: London, UK, 2016; pp. 133–152. [Google Scholar]

- Kay, T. Developing through sport: Evidencing sport impacts on young people. Sport Soc. 2009, 12, 1177–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawansky, M. You’re juicy: Autoethnography as evidence in sport for development and peace (SDP) research. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2015, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnell, S.C. Power, politics and “sport for development and peace”: Investigating the utility of sport for international development. Sociol. Sport J. 2010, 27, 54–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, M.S.; Darnell, S.C. Exploring Vietnamese sport for development through the capabilities approach: A descriptive analysis. Sport Soc. 2021, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidd, B. A new social movement: Sport for development and peace. Sport Soc. 2008, 11, 370–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekholm, D. Problematizing the concept of transfer in sports-based interventions. In Proceedings of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) Virtual Event: The Impact of Sport and Sport-Based Interventions in Preventing Youth Violence, Crime and Drug Use: From Research to Practice, 21 January 2021; Available online: https://www.unodc.org/dohadeclaration/en/sports/events/2021/the-impact-of-sport-and-sport-based-interventions-in-preventing-youth-violence--crime-and-drug-use_-from-research-to-practice.html (accessed on 28 May 2022).

- Welty Peachey, J.; Schulenkorf, N.; Hill, P. Sport-for-development: A comprehensive analysis of theoretical and conceptual advancements. Sport Manag. Rev. 2020, 23, 783–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalip, L. Toward a Distinctive Sport Management Discipline. J. Sport Manag. 2006, 20, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugden, J. Critical left-realism and sport interventions in divided societies. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2010, 45, 258–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulenkorf, N. Sustainable community development through sport and events: A conceptual framework for sport-for-development projects. Sport Manag. Rev. 2012, 15, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schulenkorf, N.; Siefken, K. Managing sport-for-development and healthy lifestyles: The sport-for-health model. Sport Manag. Rev. 2019, 22, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coalter, F. A Wider Social Role for Sport: Who’s Keeping the Score? Routledge: Oxford, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda-Parr, S. From the Millennium Development Goals to the Sustainable Development Goals: Shifts in purpose, concept, and politics of global goal setting for development. Gend. Dev. 2016, 24, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsey, I.; Darby, P. Sport and the Sustainable Development Goals: Where is the policy coherence? Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2019, 54, 793–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations High Commission for Human Rights. Claiming the Millennium Development Goals: A Human Rights Approach; United Nations: New York, NY, USA; Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kay, T.; Dudfield, O. The Commonwealth Guide to Advancing Development through Sport; Commonwealth Secretariat: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2022).

- Razavi, S. The 2030 Agenda: Challenges of implementation to attain gender equality and women’s rights. Gend. Dev. 2016, 24, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidd, B.; Donelly, P. Literature Reviews on Sport for Development and Peace; International Working Group on Sport for Development and Peace: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2007; p. 195. [Google Scholar]

- Cronin, Ó. Mapping Research on the Impact of Sport and Development Interventions. In Comic Relief Review; Órla Cronin Research: Manchester, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Van Eekeren, F.; Ter Horst, K.; Fictorie, D. Sport for Development: The Potential Value and Next Steps Review of Policy, Programs and Academic Research 1998–2013; Utrecht University: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Langer, L. Sport for development—a systematic map of evidence from Africa. S. Afr. Rev. Sociol. 2015, 46, 66–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruner, M.W.; Hillier, S.; Baillie, C.P.; Lavallee, L.F.; Bruner, B.G.; Hare, K.; Lovelace, R.; Lévesque, L. Positive youth development in Aboriginal physical activity and sport: A systematic review. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 2016, 1, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hermens, N.; Super, S.; Verkooijen, K.T.; Koelen, M.A. A Systematic Review of Life Skill Development Through Sports Programs Serving Socially Vulnerable Youth. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2017, 88, 408–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, N.L.; Neely, K.C.; Slater, L.G.; Camiré, M.; Côté, J.; Fraser-Thomas, J.; MacDonald, D.; Strachan, L.; Tamminen, K.A. A grounded theory of positive youth development through sport based on results from a qualitative meta-study. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2017, 10, 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, G.J.; Edwards, M.B.; Bocarro, J.N.; Bunds, K.S.; Smith, J.W. An integrative review of sport-based youth development literature. Sport Soc. 2017, 20, 161–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardam, K.; Giles, A.R.; Hayhurst, L.M.C. Sport for development for Aboriginal youth in Canada: A scoping review. J. Sport Dev. 2017, 5, 30–40. [Google Scholar]

- Svensson, P.G.; Woods, H. A Systematic Overview of Sport for Development and Peace Organizations. Sport Dev. 2017, 5, 36–48. [Google Scholar]

- Hancock, M.; Lyras, A.; Ha, J.-P. Sport for development programs for girls and women: A global assessment. J. Sport Dev. 2013, 1, 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford, S. ‘You look like a machito!’: A decolonial analysis of the social in/exclusion of female participants in a Colombian sport for development and peace organization. Sport Soc. 2019, 22, 1025–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxford, S.; Spaaij, R. Gender relations and sport for development in Colombia: A decolonial feminist analysis. Leis. Sci. 2019, 41, 54–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxford, S.; McLachlan, F. ”You Have to Play Like a Man, But Still be a Woman”: Young Female Colombians Negotiating Gender Through Participation in a Sport for Development and Peace (SDP) Organization. Sociol. Sport J. 2018, 35, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V.; Weate, P. Using thematic analysis in sport and exercise research. In Routledge Handbook of Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise; Sparkes, A.C., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 213–227. [Google Scholar]

- Maguire, M.; Delahunt, B. Doing a thematic analysis: A practical, step-by-step guide for learning and teaching scholars. All Irel. J. High. Educ. 2017, 9, 3351–3359. [Google Scholar]

- McDermott, L. Exploring intersections of physicality and female-only canoeing experiences. Leis. Stud. 2004, 23, 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittington, A. Challenging girls’ constructions of femininity in the outdoors. J. Exp. Educ. 2006, 28, 205–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ingen, C. Shape Your Life and Embrace Your Aggression: A Boxing Project for Female and Trans Survivors of Violence. Women Sport Phys. Act. J. 2011, 20, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodcock, A.; Cronin, Ó.; Forde, S. Quantitative evidence for the benefits of Moving the Goalposts, a Sport for Development project in rural Kenya. Eval. Program Plan. 2012, 35, 370–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musangeya, E.E.; Muchechetere, J. Empowering Girls and Young Women through Sport: A Case Study of Zimbabwe’s YES Programme. Int. J. Sport Soc. 2013, 3, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayhurst, L.M.C.; MacNeill, M.; Kidd, B.; Knoppers, A. Gender relations, gender-based violence and sport for development and peace: Questions, concerns and cautions emerging from Uganda. Women’s Stud. Int. Forum 2014, 47, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawansky, M.; Mitra, P. Family matters: Studying the role of the family through the eyes of girls in an SfD programme in Delhi. Sport Soc. 2015, 18, 983–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayhurst, L.M.C.; Giles, A.R.; Radforth, W.M.; Vancouver, A. ”I want to come here to prove them wrong”: Using a post-colonial feminist participatory action research (PFPAR) approach to studying sport, gender and development programmes for urban Indigenous young women. Sport Soc. 2015, 18, 952–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zipp, S. Sport for development with ‘at risk’ girls in St. Lucia. Sport Soc. 2016, 20, 1917–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meyer, K.; Roche, K.M. Sports-for-development gender equality impacts from basketball programme: Shifts in attitudes and stereotyping in Senegalese youth and coaches. J. Sport Dev. 2017, 5, 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Bankar, S.; Collumbien, M.; Das, M.; Verma, R.K.; Cislaghi, B.; Heise, L. Contesting restrictive mobility norms among female mentors implementing a sport based programme for young girls in a Mumbai slum. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seal, E.; Sherry, E. Exploring empowerment and gender relations in a sport for development program in Papua New Guinea. Sociol. Sport J. 2018, 35, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cislaghi, B.; Bankar, S.; Verma, R.K.; Heise, L.; Collumbien, M. Widening cracks in patriarchy: Mothers and daughters navigating gender norms in a Mumbai slum. Cult. Health Sex. 2020, 22, 166–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyon, D.; Owen, S.; Osborne, M.; Blake, K.; Andrades, B. Left/Write//Hook: A mixed method study of a writing and boxing workshop for survivors of childhood sexual abuse and trauma. Int. J. Wellbeing 2020, 10, 64–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnett, C. Participatory action research (PAR) in monitoring and evaluation of sport-for-development programmes: Sport and physical activity. Afr. J. Phys. Health Educ. Recreat. Danc. 2008, 14, 225–239. [Google Scholar]

- Petticrew, M.; Roberts, H. Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Oxford, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Burnett, C.; Uys, T. Sport development impact assessment: Towards a rationale and tool. S. Afr. J. Res. Sport Phys. Educ. Recreat. 2000, 22, 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- Schulenkorf, N.; Adair, D. Global Sport-for-Development: Critical Perspectives; Schulenkorf, N., Adair, D., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sugden, J. Teaching and Playing Sport for Conflict Resolution and Co-Existence in Israel. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2006, 41, 221–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coalter, F. The World Cup and social cohesion: Bread and circuses or bread and butter? Bull. Int. Counc. Sport Sci. Phys. Educ. 2008, 53, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Brest, P. The power of theories of change. Stanf. Soc. Innov. Rev. 2010, 8, 47–51. [Google Scholar]

- Freudberg, H.; Contractor, S.; Das, A.; Kemp, C.G.; Nevin, P.E.; Phadiyal, A.; Lal, J.; Rao, D. Process and impact evaluation of a community gender equality intervention with young men in Rajasthan, India. Cult. Health Sex. 2018, 20, 1214–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairnduff, S. Sport and Recreation for Indigenous Youth in the Northern Territory: Scoping Research Priorities for Health and Social Outcomes Report; Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal and Tropical Health, Australian Sports Commission: Darwin, Australia, 2001.

- Houlihan, B. Introduction: The problems of policy evaluation. In The Routledge Handbook of Sports Development; Houlihan, B., Green, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2011; pp. 557–560. [Google Scholar]

- Sherry, E.; Schulenkorf, N.; Phillips, P. Evaluating sport development. In Managing Sport Development: An International Approach, 1st ed.; Sherry, E., Schulenkorf, N., Phillips, P., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 161–176. [Google Scholar]

- Oatley, C.; Harris, K. How, and why, does participatory evaluation work for actors involved in the delivery of a sport-for-development initiative? Manag. Sport Leis. 2021, 26, 206–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, K.; Adams, A. Power and discourse in the politics of evidence in sport for development. Sport Manag. Rev. 2016, 19, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Hayhurst, L.M.C.; Thorpe, H.; Chawansky, M. Feminist Approaches to Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning. In Sport, Gender and Development; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2021; pp. 191–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raw, K.; Sherry, E.; Schulenkorf, N. Managing Sport for Development: An Investigation of Tensions and Paradox. Sport Manag. Rev. 2021, 25, 134–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorpe, H.; Chawansky, M. Gender, embodiment and reflexivity in everyday spaces of development in Afghanistan. Gend. Place Cult. 2021, 28, 370–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joachim, G.; Schulenkorf, N.; Schlenker, K.; Frawley, S. Design thinking and sport for development: Enhancing organizational innovation. Manag. Sport Leis. 2019, 25, 175–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsey, I.; Chapman, T.; Dudfield, O. Configuring relationships between state and non-state actors: A new conceptual approach for sport and development. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2020, 12, 127–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose Taylor, S. UN Women’s feminist engagement with governance by indicators in the Millennium and Sustainable Development Goals. Glob. Soc. Policy 2020, 20, 352–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zipp, S.; Nauright, J. Levelling the playing field: Human capability approach and lived realities for sport and gender in the West Indies. J. Sport Dev. 2018, 6, 38–50. [Google Scholar]

- Coalter, F. Sport-for-change: Some thoughts from a sceptic. Soc. Incl. 2015, 3, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richey, L.A.; Brockington, D. Celebrity humanitarianism: Using tropes of engagement to understand north/south relations. Perspect. Politics 2020, 18, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgs, C. Implementing the Commonwealth Guide to Advancing Development through Sport: A Workbook for Analysis, Planning and Monitoring; The Commonwealth: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

| Authors | Year Published | Study Approach | Instruments/Techniques of Data Collection |

|---|---|---|---|

| McDermott [71] | 2004 | Qualitative | Interviews, participant observations |

| Whittington [72] | 2006 | Qualitative | Interviews, focus group discussions, parent surveys, journal entries and other written documents (secondary data) |

| Van Ingen [73] | 2011 | Qualitative | Interviews, focus group discussions (action research project) |

| Woodcock et al. [74] | 2012 | Quantitative | Questionnaire (cross-sectional survey) |

| Hayhurst [9] | 2013 | Qualitative | Interviews, participant observations, document analysis |

| Musangeya and Muchechetere [75] | 2013 | Qualitative | Interviews, focus group discussions |

| Hayhurst et al. [76] | 2014 | Qualitative | Interviews, participant observations |

| Chawansky and Mitra [77] | 2015 | Qualitative | Interviews, focus group discussions, creative drawing in small groups |

| Hayhurst et al. [78] | 2015 | Qualitative | Interviews, photovoice (participatory action research) |

| Zipp [79] | 2016 | Qualitative | Focus group discussions |

| Meyer and Roche [80] | 2017 | Quantitative | The Attitudes towards Woman Scale for Adolescents, the Gender-Equitable Men (GEM) Scale |

| Bankar et al. [81] | 2018 | Qualitative | Interviews |

| Seal and Sherry [82] | 2018 | Qualitative | Interviews, observations, reflective journaling (participatory action research) |

| Cislaghi et al. [83] | 2020 | Qualitative | Interviews, field observations |

| Lyon et al. [84] | 2020 | Mixed-method | Qualitative tools: journal writing, video diaries Quantitative tools: Single Category Implicit Association Task (SC-IAT), PTSD Checklist for DSM-5, Mental Health Continuum Short Form, Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale |

| Authors | Country | Profile of Participants | Women Empowerment Outcomes | Gender Equity/Equality Outcomes | Level of Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| McDermott [71] | Canada | White, heterosexual women |

|

| Micro |

| Whittington [72] | United States of America | Young women who are primarily white, living in rural areas of Maine |

|

| Micro |

| Van Ingen [73] | Canada | Women and trans survivors of violence |

|

| Micro |

| Woodcock et al. [74] | Kenya | Young women from different religious backgrounds (aged 10–25 years) |

|

| Micro |

| Hayhurst [9] | Uganda | Young women facing pressing inequalities including domestic violence |

|

| Micro |

| Musangeya and Muchechetere [75] | Zimbabwe | Children and young people (aged 10–24 years) |

|

| Micro |

| Hayhurst et al. [76] | Uganda | Young women (aged 10–18 years) |

|

| Micro |

| Chawansky and Mitra [77] | India | Young women in urban areas |

|

| Micro |

| Hayhurst et al. [78] | Canada | Aboriginal young women engaged through a community center |

|

| Micro |

| Zipp [79] | St. Lucia | Young women who have behavioral problems, suffered from negligence and abuse at home (aged 12–17 years) |

|

| Micro |

| Meyer and Roche [80] | Senegal | Young men and women |

|

| Micro |

| Bankar et al. [81] | India | Young women (aged 12–16 years); women mentors (aged 18–24 years) |

|

| Meso (mentor) |

| Seal and Sherry [82] | Papua New Guinea | Indigenous women (aged 12–18 years) |

|

| Meso (staff) |

| Cislaghi et al. [83] | India | Young women living in a slum (aged 12–16 years) |

|

| Meso (family) |

| Lyon et al. [84] | Australia | Women who suffered child sexual abuse (aged 18–65 years) |

|

| Micro |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chong, Y.-Y.; Sherry, E.; Harith, S.; Khoo, S. Sport for Development Programs Contributing to Sustainable Development Goal 5: A Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6828. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116828

Chong Y-Y, Sherry E, Harith S, Khoo S. Sport for Development Programs Contributing to Sustainable Development Goal 5: A Review. Sustainability. 2022; 14(11):6828. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116828

Chicago/Turabian StyleChong, Yong-Yee, Emma Sherry, Sophia Harith, and Selina Khoo. 2022. "Sport for Development Programs Contributing to Sustainable Development Goal 5: A Review" Sustainability 14, no. 11: 6828. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116828

APA StyleChong, Y.-Y., Sherry, E., Harith, S., & Khoo, S. (2022). Sport for Development Programs Contributing to Sustainable Development Goal 5: A Review. Sustainability, 14(11), 6828. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116828