The Impact of Personal Values and Attitude toward Sustainable Entrepreneurship on Entrepreneurial Intention to Enhance Sustainable Development: Empirical Evidence from Pakistan

Abstract

:1. Introduction

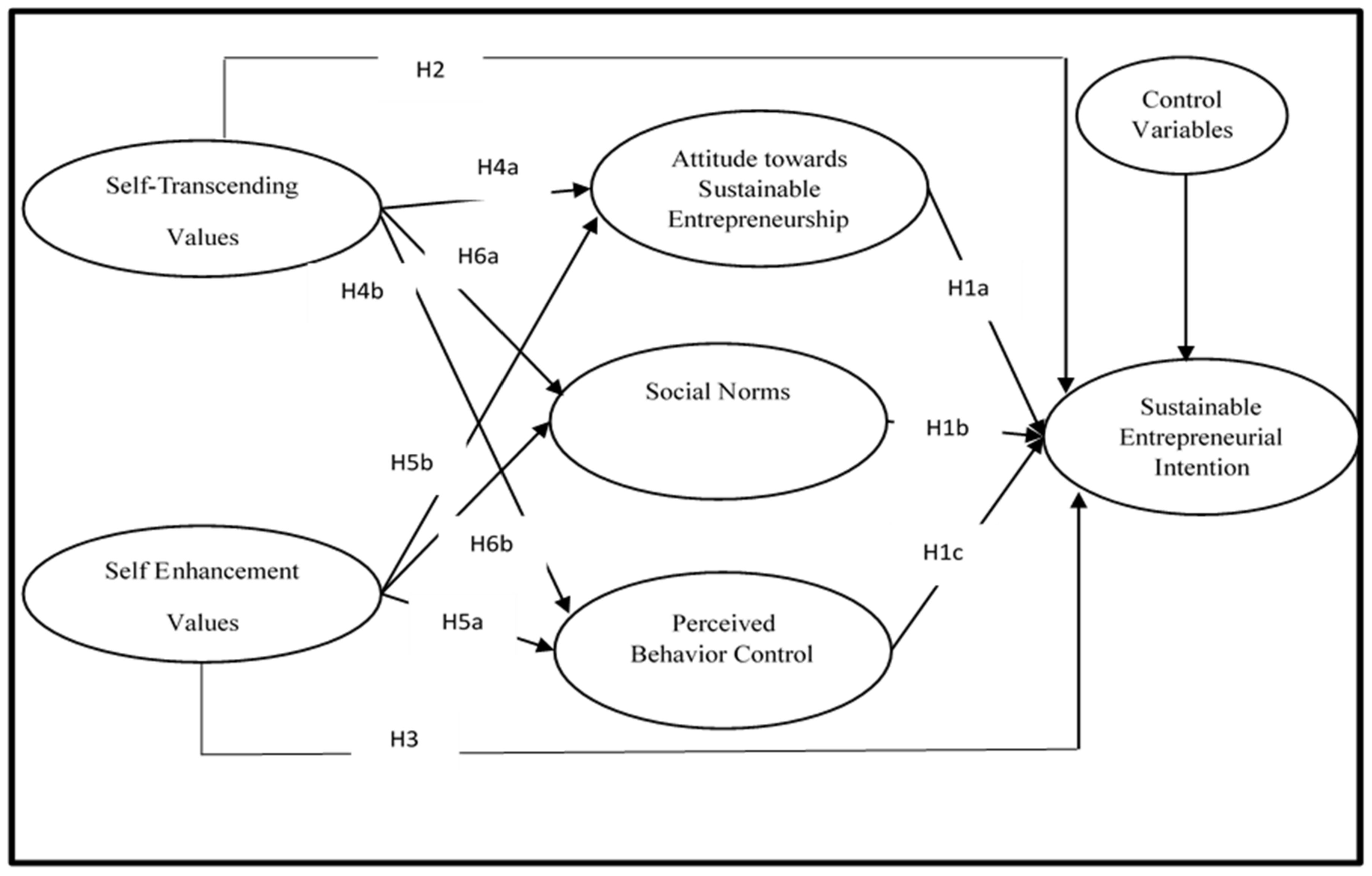

2. Theoretical Background and Development of Hypotheses

2.1. Sustainable Entrepreneurship and Sustainable Entrepreneurial Intention

2.2. Interaction between Personal Values and the Theory of Planned Behavior

2.3. Development of the Theory of Planned Behavior Dimensions to Form Sustainable Intention

2.4. Direct Relationship of Personal Values and Sustainable Entrepreneurial Intention

2.5. Integrating the Theory of Planned Behavior Dimensions and Personal Values Dimensions

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Samples, Data Collection Procedure, and Common Method Bias

3.2. The Demographics of the Respondents

3.3. Measurement Scale of the Study

3.4. Control Variables

3.5. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model

4.2. Discriminant Validity of the Study

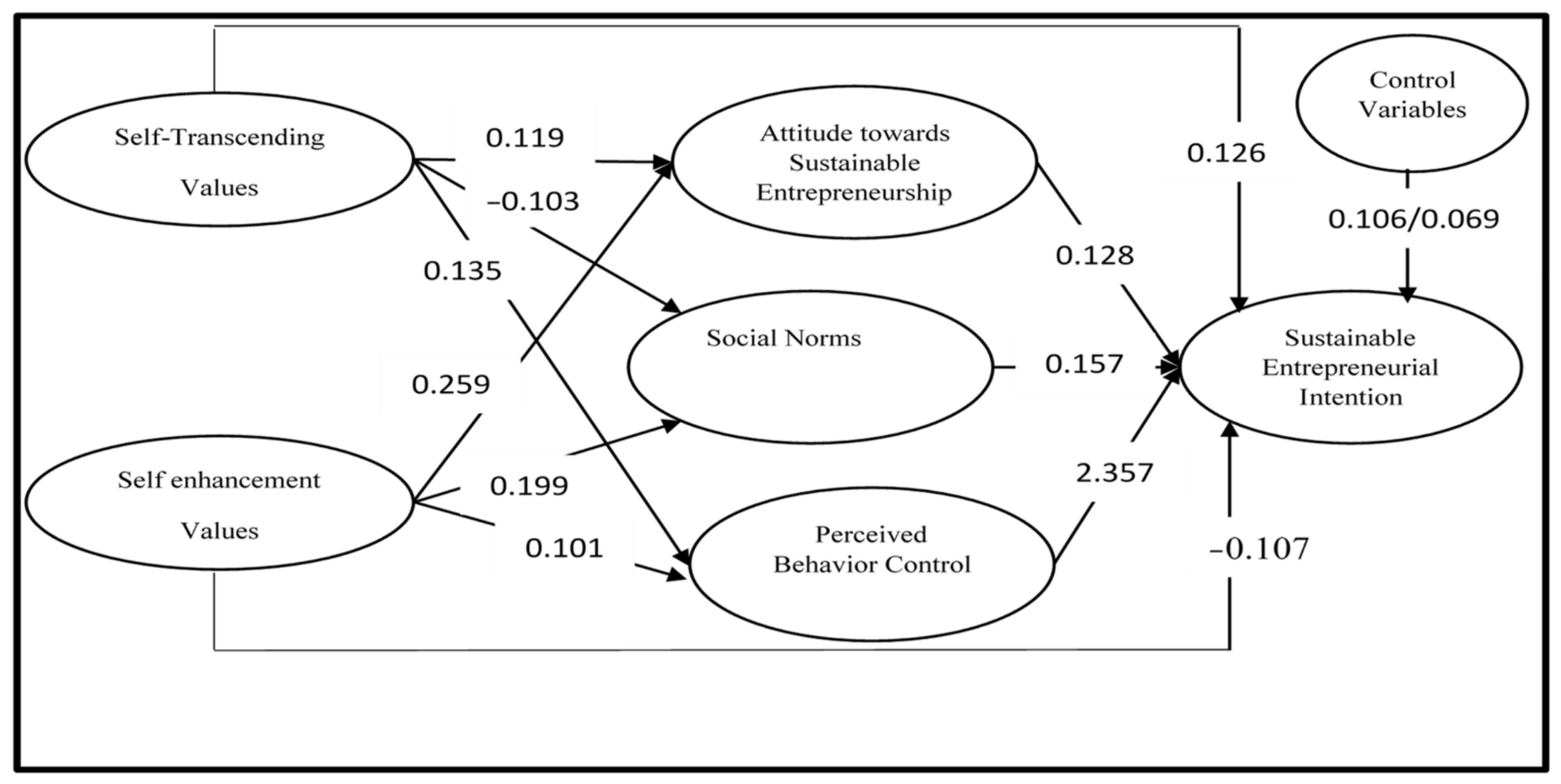

4.3. Structural Modeling Testing

4.4. Mediation Testing and Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implication

5.2. Practical Implication

6. Limitation and Future Research and Conclusions of the Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Luc, P.T. The influence of personality traits on social entrepreneurial intention among owners of civil society organizations in Vietnam. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2020, 40, 291–308. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Paray, Z.A.; Dwivedi, A.K. Student’s entrepreneurial orientation and intentions. High. Educ. Ski. Work. Learn. 2020, 11, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, S.; Biemans, H.J.; Lans, T.; Chizari, M.; Mulder, M. Effects of role models and gender on students’ entrepreneurial intentions. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2014, 38, 694–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shepherd, D.A.; Patzelt, H. The new field of sustainable entrepreneurship: Studying entrepreneurial action linking “what is to be sustained” with “what is to be developed”. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2011, 35, 137–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Youssef, A.; Boubaker, S.; Omri, A. Entrepreneurship and sustainability: The need for innovative and institutional solutions. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2018, 129, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veleva, V.; Bodkin, G. Corporate-entrepreneur collaborations to advance a circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 188, 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eikelenboom, M.; de Jong, G. The impact of dynamic capabilities on the sustainability performance of SMEs. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 235, 1360–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dees, J.G. The meaning of social entrepreneurship. In Case Studies in Social Entrepreneurship and Sustainability; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 34–42. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S.K.; Del Giudice, M.; Chierici, R.; Graziano, D. Green innovation and environmental performance: The role of green transformational leadership and green human resource management. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 150, 119762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubbs, W. Sustainable entrepreneurship and B corps. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2017, 26, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, J. Impact of total quality management on corporate green performance through the mediating role of corporate social responsibility. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 242, 118458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, B.; Al-Ghazali, B.M.; Rehman, Z.U.; Umrani, W.A. The moderating effects of employee corporate social responsibility motive attributions (substantive and symbolic) between corporate social responsibility perceptions and voluntary pro environmental behavior. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 769–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suganthi, L. Examining the relationship between corporate social responsi- bility, performance, employees’ pro-environmental behavior at work with green practices as mediator. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 232, 739–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, N.A.; Herrmann, A.M.; Hekkert, M.P. How sustainable entrepreneurs engage in institutional change: Insights from biomass torrefaction in The Netherlands. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 106, 608–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hockerts, K.; Wüstenhagen, R. Greening Goliaths versus emerging Davidsdtheorizing about the role of incumbents and new entrants in sustainable entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Munoz, P. A cognitive map of sustainable decision-making in entrepreneurship: A configurationally approach. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2018, 24, 787–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yasir, N.; Mahmood, N.; Mehmood, H.S.; Babar, M.; Irfan, M.; Liren, A. Impact of environmental, social values and the consideration of future consequences for the development of a sustainable entrepreneurial intention. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasir, N.; Mahmood, N.; Jutt, A.A.; Babar, M.; Irfan, M.; Jamil, F.; Shaukat, M.Z.; Khan, H.M.; Liren, A. How can Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy, Proactivity and Creativity Enhance Sustainable Recognition Opportunity? The Effect of Entrepreneurial Alertness Is to Mediate the Formation of Sustainable Entrepreneurial Intention. Rev. Argent. Clínica Psicol. 2020, 29, 1004–1023. [Google Scholar]

- Vuorio, A.M.; Puumalainen, K.; Fellnhofer, K. Drivers of entrepreneurial intentions in sustainable entrepreneurship. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2018, 24, 359–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liñán, F.; Moriano, J.A.; Jaén, I. Individualism and entrepreneurship: Does the pattern depend on the social context? Int. Small Bus. J. 2016, 34, 760–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, C.; Holtschlag, C.; Masuda, A.D.; Marquina, P. In which cultural contexts do individual values explain entrepreneurship? An integrative values framework using Schwartz’s theories. Int. Small Bus. J. 2019, 37, 241–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Universals in the content and structure of values: Theory and empirical tests in 20 countries. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Zanna, M., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 1–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, D.V.; Shepherd, D.A. Deciding to persist: Adversity, values, and entrepreneurs’ decision policies. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2013, 37, 331–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Studying Values: Personal Adventure, Future Directions. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 2011, 42, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, E.M.; Ramos, M.O.; Alexander, A.; Jabbour, C.J.C. A systematic review of empirical and normative decision analysis of risk in sustainability related supplier risk management. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 244, 118808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parastuty, Z.; Bögenhold, D. Paving the Way for Self-Employment: Does Society Matter? Sustainability 2019, 11, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bögenhold, D. Changing Ideas and Contours of Entrepreneurship in the History of Thought: On the Fluidity and Indefiniteness of a Term. Int. Rev. Entrep. 2019, 17, 145–168. [Google Scholar]

- Yasir, N.; Mahmood, N.; Mehmood, H.S.; Rashid, O.; Liren, A. The Integrated Role of Personal Values and Theory of Planned Behavior to Form a Sustainable Entrepreneurial Intention. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betáková, J.; Wu, J.; Rudnak, I.; Magda, R. Employment of foreign students after graduation in Hungary in the context of entrepreneurship and sustainability. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2021, 8, 553–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S.; Beckmann, M.; Hockerts, K. Collaborative entrepreneurship for sustainability. Creating solutions in light of the UN sustainable development goals. Int. J. Entrep. Ventur. 2018, 10, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belz, F.M.; Binder, J.K. Sustainable Entrepreneurship: A Convergent Process Model. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2017, 26, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linan, F.; Fayolle, A. A systematic literature review on entrepreneurial intentions: Citation, thematic analyses, and research agenda. Int. Enterpren. Manag. J. 2015, 11, 907–933. [Google Scholar]

- Dentchev, N.; Baumgartner, R.; Dieleman, H.; Johannsdottir, L.; Jonker, J.; Nyberg, T.; Rauter, R.; Rosano, M.; Snihur, Y.; Tang, X.; et al. Embracing the variety of sustainable business models: Social entrepreneurship, corporate intrapreneurship creativity, innovation, and other approaches to sustainability challenges. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 113, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieciuch, J. Exploring the complicated relationship between values and behaviour. In Values and Behavior; Roccas, S., Sagiv, L., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hueso, J.A.; Jaén, I.; Liñán, F. From personal values to entrepreneurial intention: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2020, 27, 205–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. A theory of cultural value orientations: Explications and applications. Comp. Sociol. 2006, 5, 137–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Konsky, C.; Eguchi, M.; Blue, J.; Kapoor, S. Individualist-collectivist values: American, Indian and Japanese cross-cultural study. Intercult. Commun. Stud. 2000, 9, 69–84. [Google Scholar]

- Linan, F.; Chen, Y.W. Development and Cross-Cultural application of a specific Instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 593–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasir, N.; Liren, A.; Mehmood, N.; Arfat, Y. Impact of personality traits on entrepreneurial intention and demographic factors as moderator. Int. J. Entrep. 2019, 23, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Soomro, B.A.; Shah, N.; Memon, M. Robustness of the theory of planned behaviour (TPB): A comparative study between Pakistan and Thailand. Acad. Entrep. J. 2018, 26, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Kautonen, T.; Van Gelderen, M.; Fink, M. Robustness of the theory of planned behavior in predicting entrepreneurial intentions and actions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2015, 39, 655–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Autio, E.; Keeley, R.H.; Klofsten, M.; Parker, G.C.; Hay, M. Entrepreneurial intent among students in Scandinavia and in the USA. Enterp. Innov. Manag. Stud. 2001, 2, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Kruse, P.; Wach, D.; Costa, S.; Moriano, J.A. Values matter, Don’t They?—Combining theory of planned behavior and personal values as predictors of social entrepreneurial intention. J. Soc. Entrep. 2019, 10, 55–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israr, M.; Saleem, M. Entrepreneurial intentions among university students in Italy. J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2018, 8, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jabbour, C.J.C.; Sarkis, J.; de Sousa Jabbour, A.B.L.; Renwick, D.W.S.; Singh, S.K.; Grebinevych, O.; Kruglianskas, I.; Godinho Filho, M. Who is in charge? A review and a research agenda on the ‘human side’ of the circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 222, 793–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, B.; Yang, S.; Bi, J. Enterprises’ willingness to adopt/develop cleaner production technologies: An empirical study in Changshu, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 40, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz, P.; Dimov, D. The call of the whole in understanding the development of sustainable ventures. J. Bus. Ventur. 2015, 30, 632–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Singh, S.K.; Pradhan, R.K.; Panigrahy, N.P.; Jena, L.K. Self-efficacy and workplace well-being: Moderating role of sustainability practices. Benchmark Int. J. 2019, 26, 1692–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, C.; Jabbour, C.J.C. Understanding the human side of green hospitality management. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 88, 102389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dentoni, D.; Bitzer, V. The role(s) of universities in dealing with global wicked problems through multi-stakeholder initiatives. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 106, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambe, P.; Ndofirepi, T.M. Explaining social entrepreneurial intentions among college students in Zimbabwe. J. Soc. Entrep. 2019, 1–22, 175–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Predicting and Changing Behavior: The Reasoned Action Approach; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jaén, I.; Liñán, F. Work values in a changing economic environment: The role of entrepreneurial capital. Int. J. Manpow. 2013, 34, 939–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gorgievski, M.J.; Stephan, U.; Laguna, M.; Moriano, J.A. Predicting entrepreneurial career intentions: Values and the theory of planned behavior. J. Career Assess. 2018, 26, 457–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolzani, D.; Foo, M.D. The “why” of international entrepreneurship: Uncovering entrepreneurs’ personal values. Small Bus. Econ. 2018, 51, 639–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S.; Wagner, M. Sustainable entrepreneurship and sustainability innovation: Categories and interactions. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2011, 20, 222–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, T.J.; McMullen, J.S. Toward a theory of sustainable entrepreneurship: Reducing environmental degradation through entrepreneurial action. J. Bus. Ventur. 2007, 21, 50–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, F.M. A positive theory of social entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 111, 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Singh, A.P. Interplay of organizational justice, psychological empowerment, organizational citizenship behavior, and job satisfaction in the context of circular economy. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 937–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sher, A.; Mazhar, S.; Zulfiqar, F.; Wang, D.; Li, X. Green entrepreneurial farming: A dream or reality? J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 220, 1131–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homer, P.M.; Kahle, L.R. A structural equation test of the value attitude behavior hierarchy. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 638–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, B.; Winn, M.I. Market imperfections, opportunity and sustainable entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 2007, 22, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, D.A. Party On! A call for entrepreneurship research that is more interactive, activity based, cognitively hot, compassionate, and prosocial. J. Bus. Ventur. 2015, 30, 489–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liobikiene, G.; Juknys, R. The role of values, environmental risk perception, awareness of consequences, and willingness to assume responsibility for environmentally-friendly behaviour: The Lithuanian case. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 3413–3422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasir, N.; Liren, A.; Mahmood, N.; Mehmood, H.S. The role of personality traits, entrepreneurship education and self-efficacy as mediating effect on the entrepreneurial intention. Dilemas Contemp. Educ. Política Valore 2019, 6, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Segal, G.; Borgia, D.; Schoenfeld, J. The motivation to become an entrepreneur. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2005, 11, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Gelderen, M.; Jansen, P. Autonomy as a start-up motive. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2006, 13, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Looi, K.H. Undergraduates’ motivations for entrepreneurial intentions: The role of individualistic values and ethnicity. J. Educ. Work 2019, 32, 465–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, S.; Biemans, H.J.; Lans, T.; Mulder, M. Understanding the role of cultural orientations in the formation of entrepreneurial intentions in Iran. J. Career Dev. 2019, 48, 619–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, M.M.; Maio, G.R.; Olson, J.M. The vulnerability of values to attack: Inoculation of values and value-relevant attitudes. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 29, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthias, F.; Sascha, K.; Norat, R.-T.; Norbert, K.; Ulrike, F. Entrepreneurship as catalyst for sustainable development: Opening the black box. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4503. [Google Scholar]

- Baruch, Y.; Holtom, B.C. Survey response rate levels and trends in organizational research. Hum. Relat. 2008, 61, 1139–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wadhwa, V.; Freeman, R.; Rissing, B. Education and tech entrepreneurship. Innov. Technol. Gov. Glob. 2010, 5, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherdoost, H. Sampling methods in research methodology; how to choose a sampling technique for research. Int. J. Acad. Res. Manag. 2016, 5, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, J.A. Qualitative research design: An interactive approach. In Applied Social Research Methods Series; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’brien, R.M. A Caution Regarding Rules of Thumb for Variance Inflation Factors. Qual. Quant. 2007, 41, 673–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osgood, C.E.; Suci, G.J.; Tannenbaum, P.H. The Measurement of Meaning, 9th ed.; University of Illinois Press: Urbana, IL, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Kriyantono, R. Consumers’ internal meaning on complementary Co-branding product by using Osgood’s theory of semantic differential. J. Manag. Mark. Rev. 2017, 2, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriano, J.A.; Gorgievski, M.; Laguna, M.; Stephan, U.; Zarafshani, K. A crosscultural approach to understanding entrepreneurial intention. J. Career Dev. 2012, 39, 162–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kolvereid, L. Prediction of employment status choice intentions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1996, 21, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linan, F. Intention-based models of entrepreneurship education. Small Bus. 2004, 3, 11–35. [Google Scholar]

- Zapkau, F.B.; Schwens, C.; Steinmetz, H.; Kabst, R. Disentangling the effect of prior entrepreneurial exposure on entrepreneurial intention. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 639–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with Mplus: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Jaiswal, D.; Kant, R. Green purchasing behaviour: A conceptual framework and empirical investigation of Indian consumers. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 41, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics, 4th ed.; Harper Collins: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modelling, 2nd ed.; The Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.; Anderson, R.; Tatham, R.; Black, W. Análisis Multivariante; Pearson Prentice Hall: Madrid, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoffcriteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, B.; Kujinga, L. The institutional environment and social entrepreneurship intentions. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2017, 23, 638–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sastre-Castillo, M.A.; Peris-Ortiz, M.; Danvila-Del Valle, I. What Is Different about the Profile of the Social Entrepreneur? Nonprofit Manag. Leadersh. 2015, 25, 349–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, S.T.; Higgins, C.A.; Duxbury, L. Work values: Development of a new three-dimensional structure based on confirmatory smallest space analysis. J. Organ. Behav. 2010, 31, 969–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkley, W.W. Entrepreneurial behaviour: The role of values. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2016, 22, 290–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Lynch, J.G., Jr.; Chen, Q. Reconsidering baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koe, W.L.; Majid, I.A. Socio-Cultural factors and intention towards sustainable entrepreneurship. Eurasian J. Bus. Econ. 2014, 7, 145–156. [Google Scholar]

- Fayolle, A.; Linan, F.; Moriano, J.A. Beyond entrepreneurial intentions: Values and motivations in entrepreneurship. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2014, 10, 679–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koe, W.-L.; Omar, R.; Sa’ari, J.R. Factors influencing propensity to sustainable entrepreneurship of SMEs in Malaysia. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 172, 570–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Douglas, E.J.; Fitzsimmons, J.R. Interaction between feasibility and desirability in the formation of entrepreneurial intentions. In Proceedings of the SEAANZ 2005 Conference, Armidale, Australia, 25–28 September 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, B.; Jiang, D.; Gao, Y.; Tsai, S.-B. The influence of legitimacy on a proactive green orientation and green performance: A study based on transitional economy scenarios in China. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kuckertz, A.; Wagner, M. The influence of sustainability orientation on entrepreneurial intentions—Investigating the role of business experience. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 524–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. Special Topic Report Social Entrepreneurship. 2016. Available online: http://gemconsortium.org/report/49542 (accessed on 28 August 2019).

- Bacq, S.; Alt, E. Feeling capable and valued: A prosocial perspective on the link between empathy and social entrepreneurial intentions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2018, 33, 333–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Variables | Frequency | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 287 | 61.7% |

| Female | 178 | 38.3% |

| Age | ||

| Below 25 | 303 | 65.3% |

| Above 25 | 162 | 34.8% |

| Level of Education | ||

| Master | 247 | 53.1% |

| Bachelor | 218 | 46.9% |

| Area of Study | ||

| Engineering | 273 | 58.7% |

| Business | 192 | 41.3% |

| Founding Experience | ||

| Yes | 266 | 57.2% |

| No | 199 | 42.8% |

| Sustainable Entrepreneurial Education | ||

| Yes | 288 | 61.9% |

| No | 177 | 38.1% |

| Construct | Measurement Items | FL | α | CR | AVE | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-transcending values [38] | It is critical that everyone on the planet get the same level of respect. | 0.739 | 0.905 | 0.905 | 0.615 | 2.206 |

| Every person should be given the same chances in life. | 0.785 | 2.88 | ||||

| Helping others is quite essential. Their health and well-being are important to her/his heart. | 0.773 | 2.465 | ||||

| Correcting injustice and looking out for the vulnerable are two of the main tenets of social justice. | 0.791 0.782 | 2.479 2.245 | ||||

| A world without conflict and war. | 0.831 | 2.121 | ||||

| Self-enhancing values [38] | He/she places a great deal of importance on being a successful person. He/she enjoys making others feel good about themselves | 0.777 | 0.901 | 0.921 | 0.625 | 2.058 |

| The right to command and lead. | 0.828 | 2.527 | ||||

| Ambitious people are diligent and aspiring. | 0.799 | 2.540 | ||||

| A person’s ability to exert influence on others is known as social power. | 0.789 | 2.515 | ||||

| Satisfaction of desires: pleasure. | 0.777 | 2.206 | ||||

| People who like eating, sex, and other pleasures in life are more likely to be happy. | 0.826 | 2.060 | ||||

| Self-gratification: fulfilment and satisfaction. | 0.737 | 1.807 | ||||

| Attitude toward sustainable entrepreneurship [81,82] | I see more advantages to becoming a sustainable entrepreneur than negatives. | 0.708 | 0.896 | 0.920 | 0.658 | 1.689 |

| I am interested in pursuing a career in sustainable entrepreneurship. | 0.838 | 2.540 | ||||

| In the event I had the opportunity and resources, I would like to create a long-term business. | 0.831 | 2.434 | ||||

| I believe that being a socially responsible entrepreneur would bring me enormous joy. | 0.817 | 2.230 | ||||

| Instead of working for someone else, I would prefer to work for myself as a sustainable entrepreneur. | 0.850 | 2.584 | ||||

| As a sole proprietor, I would be able to make a significant dent in environmental issues. | 0.817 | 2.142 | ||||

| Subjective norms [83] | Your close family. | 0.882 | 0.869 | 0.920 | 0.793 | 2.152 |

| Your friends. | 0.909 | 2.634 | ||||

| Your fellow students. | 0.880 | 2.236 | ||||

| Perceived behavior control [40,84] | We provide the expertise you need to launch a long-term business. | 0.828 | 0.885 | 0.912 | 0.633 | 2.328 |

| You have a good chance of success if you create a sustainable business. | 0.835 | 2.567 | ||||

| Build a sustainable business from scratch. | 0.745 | 2.053 | ||||

| If you want to become a long-term entrepreneur, you can easily do it. | 0.814 | 2.446 | ||||

| For me, starting my own business and becoming a long-term entrepreneur is a piece of cake. | 0.792 | 2.430 | ||||

| Identify new product and/or service market opportunities. | 0.757 | 2.049 | ||||

| Sustainable entrepreneurial intention [40,44] | Sustainable entrepreneurship is the ultimate goal of my profession. | 0.704 | 0.886 | 0.913 | 0.638 | 1.580 |

| In the next five years, I plan to develop a company that will focus on environmental issues. | 0.821 | 2.344 | ||||

| As a result of your entrepreneurial endeavors, we will work to promote environmentally friendly practices. | 0.827 | 2.612 | ||||

| As a business owner, I am conscious of how I use natural resources. | 0.828 | 2.498 | ||||

| As an entrepreneur, I use natural resources in a responsible way. | 0.835 | 2.457 | ||||

| If I decide to start a firm of my own, I intend to prioritize social benefits over financial ones. | 0.771 | 1.837 |

| Demographic Variables | CMIN/df | AGFI | GFI | CFI | NFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model fit indicators | 2.085 | 0.942 | 0.952 | 0.941 | 0.936 | 0.042 |

| Suggested values | <3 | >90 | >90 | >90 | >90 | <0.05 |

| Self-T | Self-E | ATS | SN | PBC | SEI | EE | SEE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-T | 0.784 | |||||||

| Self-E | −0.20 ** | 0.790 | ||||||

| ATS | 0.36 *** | −0.12 ** | 0.811 | |||||

| SN | 0.09 * | 0.07 | 0.25 *** | 0.890 | ||||

| PBC | 0.16 *** | 0.05 | 0.43 ** | 0.15 * | 0.795 | |||

| SEI | 0.22 ** | −0.05 | 0.70 * | 0.17 | 0.51 ** | 0.798 | ||

| EE a | 0.00 | −0.14 * | 0.11 *** | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.18 | 1 | |

| SEE a | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.17 *** | −0.04 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.02 | 1 |

| Constructs | Direct Effect | t-Values | p Values | Hypothesis | Significant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATS → SEI | 0.128 | 3.137 | 0.000 | H1a | Yes |

| SN → SEI | 0.157 | 4.127 | 0.000 | H1b | Yes |

| PBC → SEI | 2.357 | 8.098 | 0.000 | H1c | Yes |

| Self-E → SEI | −0.107 | 3.080 | 0.002 | H2 | Yes |

| Self-T → SEI | 0.126 | 3.323 | 0.001 | H3 | Yes |

| Self-T → ATS | 0.119 | 3.028 | 0.010 | Yes | |

| Self-T → SN | −0.103 | −1.137 | 0.256 | No | |

| Self-T → PBC | 0.135 | 3.893 | 0.000 | Yes | |

| Self-E → ATS | 0.259 | 7.049 | 0.000 | Yes | |

| Self-E → SN | 0.199 | 3.669 | 0.000 | Yes | |

| Self-E → PBC | 0.101 | 0.053 | 1.897 | No | |

| Entrepreneur Exposure | 0.106 | 3.238 | 0.001 | Control variable | Yes |

| Entrepreneurship Education | 0.069 | 2.637 | 0.010 | Control variable | Yes |

| Mediation | Estimate(β) | p-Values | Lower Threshold | Upper Threshold | Hypothesis | Mediation Types | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-T → ATS → SEI | 0.135 | 0.000 | 0.094 | 0.181 | H4a | Complementary partial mediation | supported |

| Self-T → SN → SEI | 0.001 | 0.851 | −0.013 | 0.014 | H4b | No effect | Not supported |

| Self-T → PBC → SEI | 0.026 | 0.062 | 0.004 | 0.057 | H4c | Complementary partial mediation | Supported |

| Self-E → ATS → SEI | 0.065 | 0.001 | 0.031 | 0.105 | H5a | Complementary partial mediation | Supported |

| Self-E → SN → SEI | 0.049 | 0.002 | 0.023 | 0.086 | H5b | Complementary partial mediation | Supported |

| Self-E → PBC → SEI | 0.034 | 0.199 | −0.011 | 0.076 | H5c | No effect | Not supported |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yasir, N.; Xie, R.; Zhang, J. The Impact of Personal Values and Attitude toward Sustainable Entrepreneurship on Entrepreneurial Intention to Enhance Sustainable Development: Empirical Evidence from Pakistan. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6792. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116792

Yasir N, Xie R, Zhang J. The Impact of Personal Values and Attitude toward Sustainable Entrepreneurship on Entrepreneurial Intention to Enhance Sustainable Development: Empirical Evidence from Pakistan. Sustainability. 2022; 14(11):6792. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116792

Chicago/Turabian StyleYasir, Nosheena, Ruyu Xie, and Junrui Zhang. 2022. "The Impact of Personal Values and Attitude toward Sustainable Entrepreneurship on Entrepreneurial Intention to Enhance Sustainable Development: Empirical Evidence from Pakistan" Sustainability 14, no. 11: 6792. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116792

APA StyleYasir, N., Xie, R., & Zhang, J. (2022). The Impact of Personal Values and Attitude toward Sustainable Entrepreneurship on Entrepreneurial Intention to Enhance Sustainable Development: Empirical Evidence from Pakistan. Sustainability, 14(11), 6792. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116792