Great Resignation—Ethical, Cultural, Relational, and Personal Dimensions of Generation Y and Z Employees’ Engagement

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Work Engagement among Generations Y and Z

- At my work, I feel bursting with energy;

- At my job, I feel strong and vigorous;

- When I get up in the morning, I feel like going to work;

- I can continue working for very long periods at a time;

- At my job, I am very resilient, mentally;

- At my work, I always persevere, even when things do not go well.

- I find the work that I do full of meaning and purpose;

- I am enthusiastic about my job;

- My job inspires me;

- I am proud of the work that I do;

- To me, my job is challenging.

- Time flies when I’m working;

- When I am working, I forget everything else around me;

- I feel happy when I am working intensely;

- I am immersed in my work;

- I get carried away when I’m working;

- It is difficult to detach myself from my job.

- I focus hard on my work;

- I concentrate on my work;

- I pay a lot of attention to my work;

- I share the same work values as my colleagues;

- I share the same work goals as my colleagues;

- I share the same work attitudes as my colleagues;

- I feel positive about my work;

- I feel energetic in my work;

- I am enthusiastic about my work [20].

- I know what is expected of me at work;

- I have the materials and equipment I need to do my work right;

- At work, I have the opportunity to do what I do best every day;

- In the last seven days, I have received recognition or praise for doing good work;

- My supervisor, or someone at work, seems to care about me as a person.;

- There is someone at work who encourages my development;

- At work, my opinions seem to count;

- The mission or purpose of my company makes me feel my job is important;

- My associates and fellow employees are committed to doing quality work;

- I have a best friend at work;

- In the last six months, someone at work has talked to me about my progress;

- This last year, I have had opportunities at work to learn and grow [21].

- Flexibility;

- Work-life balance;

- Continuous development;

- Working with an interesting technological stack [25].

- Company engagement in climate change;

- Commitment to fighting hunger and social exclusion;

- Sustainable development;

- Broadly understood diversity, equity, and inclusion;

- Personalization in career planning and development;

- Extensive learning and development opportunities [29].

- A good working atmosphere;

- Being treated with respect;

- Good development opportunities at work;

- Self-realization;

- Corporate values and ethics;

- Trust [30].

- Strong corporate values;

- Engagement in diversity, equity, and inclusion actions;

- Sustainable devlelopment and environmental protection;

- Interesting and fulfilling tasks [31].

3. Materials and Methods

- Research gap: (1) Although there is a couple of studies on the topic of Great Resignation, they are mostly related to the United States [32]; (2) additionally, what is lacking, is the perspective of a startup company, as most of the analysis comes from the corporate world.

- Scientific significance: The research will provide a new perspective on the work engagement of the young generations (Generation Y and Z) and its shape after the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Practical application: For business leaders and human resources specialists, a deeper understanding of the actual reasons for Great Resignation will help design relevant engagement strategies and appealing company culture

- Primary source data collection (surveys, in-depth interviews)

- Secondary research data collection.

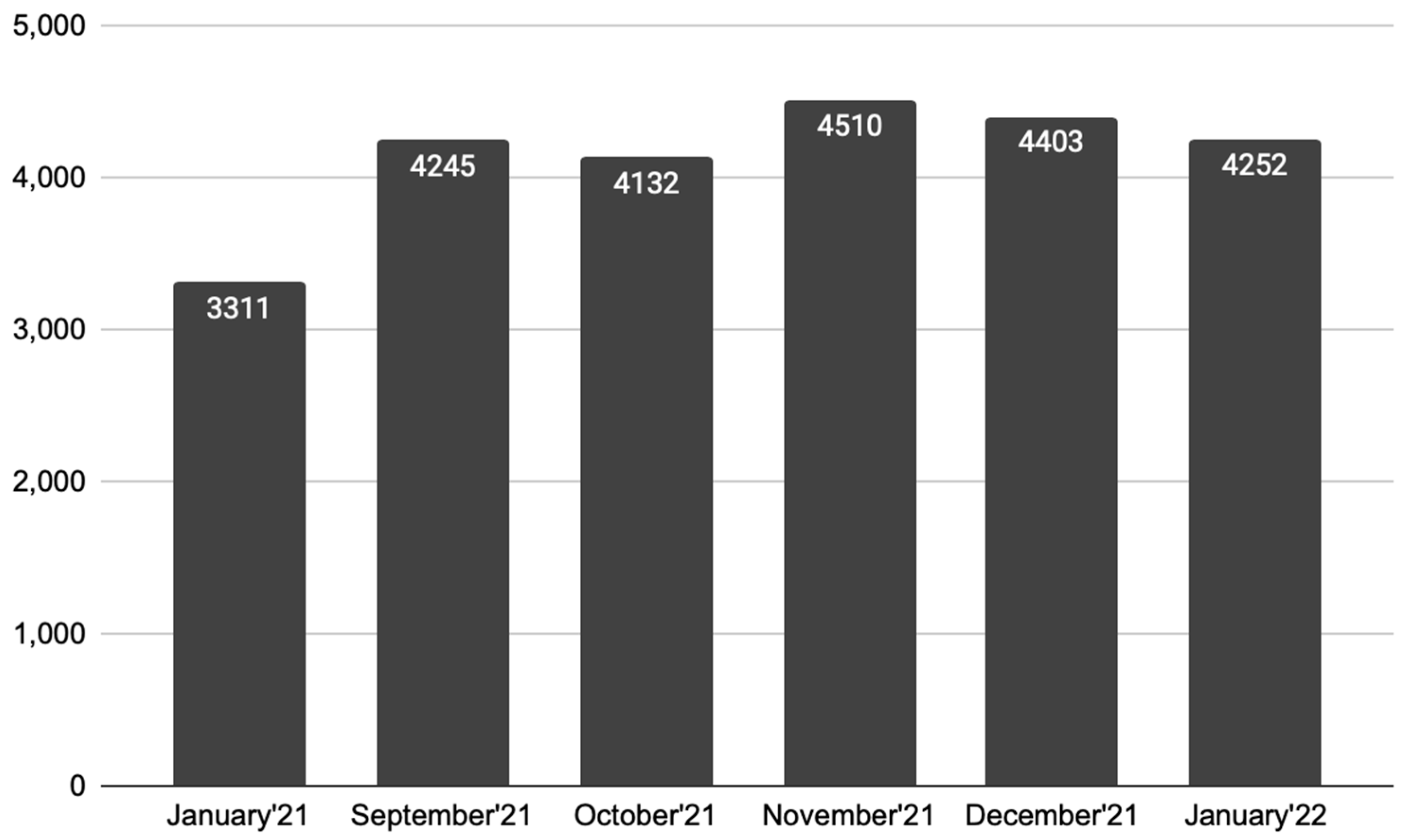

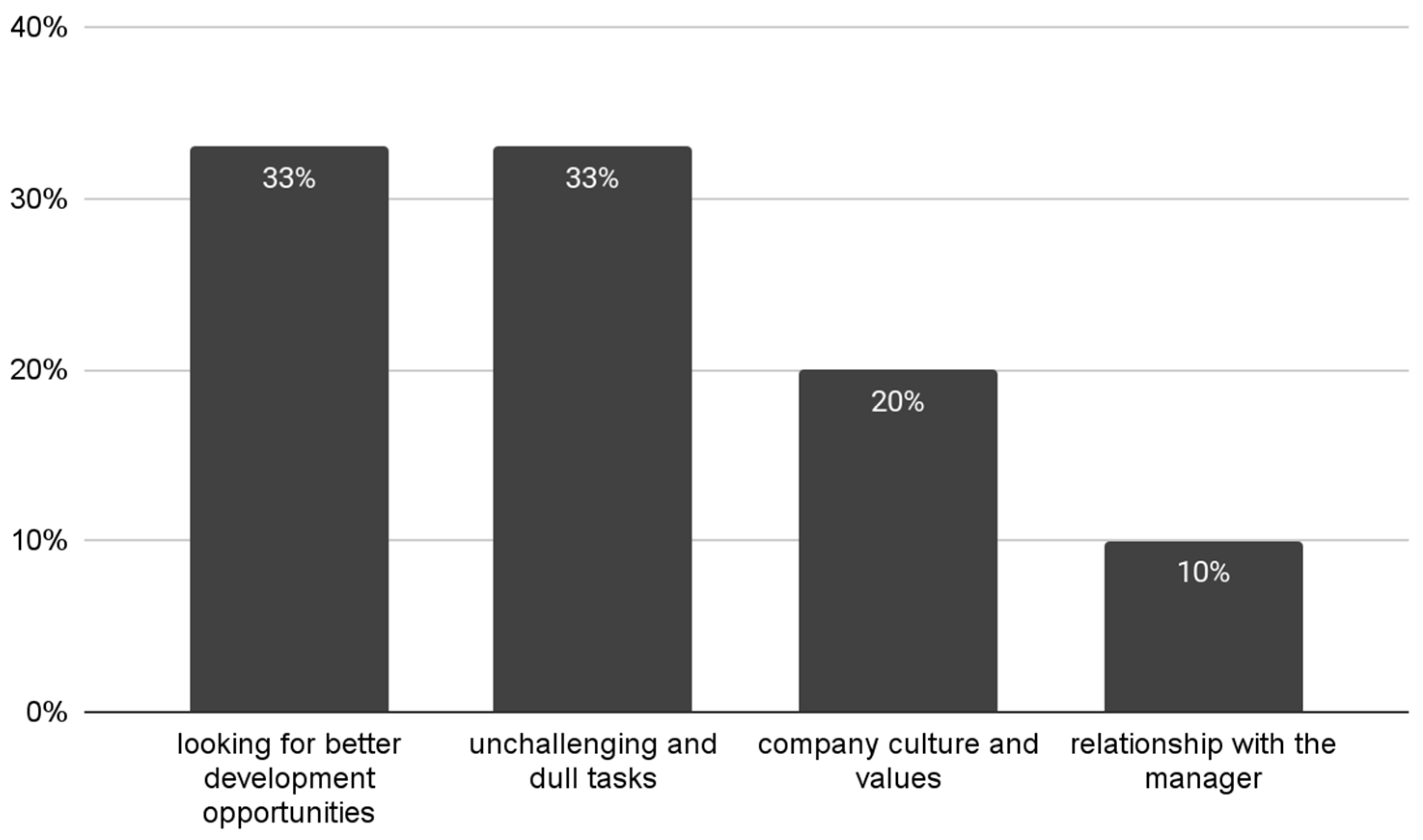

4. Results

- Compensation;

- Work-life balance;

- Poor physical and emotional health.

- Not feeling valued by their organizations (54%);

- Not being valued by the managers (52%);

- Lack of sense of belonging at work (51%) [37].

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bayraktar, M. The Great Resignation of US Labor Force. 1 March 2022. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4047174 (accessed on 3 May 2022).

- Kuzior, A.; Kettler, K.; Rąb, Ł. Digitalization of Work and Human Resources Processes as a Way to Create a Sustainable and Ethical Organization. Energies 2021, 15, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzior, A.; Mańka-Szulik, M.; Krawczyk, D. Changes in the Management of Electronic Public Services in the Metropolis During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2021, 24, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyulyov, O.; Us, Y.; Pimonenko, T.; Kwilinski, A.; Vasylieva, V.; Dalevska, N.; Polcyn, J.; Boiko, V. The Link Between Economic Growth and Tourism: COVID-19 Impact. In Proceedings of the 36th International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), Granada, Spain, 4–5 November 2020; pp. 8070–8086. [Google Scholar]

- Kuzior, A.; Mańka-Szulik, M.; Marszałek-Kotzur, I. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the economic and psychological condition of individuals and societies. In Proceedings of the 37th International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), Cordoba, Spain, 1–2 April 2021; pp. 8129–8135. [Google Scholar]

- Bloomberg.com. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-05-10/quit-your-job-how-to-resign-after-covid-pandemic?sref=85rT08Vo (accessed on 3 May 2022).

- Bls.gov. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/jolts.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- Chicagofed.org. Available online: https://www.chicagofed.org/publications/chicago-fed-letter/2022/465#:~:text=According%20to%20our%20estimates%2C%20the,declined%20slightly%20in%20September%202021 (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- Slater, A. Rising quit rates are a possible inflation signal. Econ. Outlook 2022, 46, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiskrova, K.G. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the workforce: From psychological distress to the Great Resignation. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2022, 76, 525–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheather, J.; Slattery, D. The great resignation—how do we support and retain staff already stretched to their limit? BMJ 2021, 375, 2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Businessleader.co.uk. Available online: https://www.businessleader.co.uk/the-great-resignation-and-how-it-can-be-turned-into-the-great-reshuffle (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Amburgey, A.; Birinci, S. The Great Resignation vs. The Great Reallocation: Industry-Level Evidence. Econ. Synop. Fed. Reserve Bank St. Louis 2022, 4, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch, P.B. The Great Discontent. J. Bus. Strategy 2021, 42, 439–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sull, D.; Sull, C.; Zweig, B. Toxic Culture Is Driving the Great Resignation. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2022, 63, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, W.A. Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 692–724. [Google Scholar]

- Rich, B.L.; Lepine, J.A.; Crawford, E. Job Engagement: Antecedents and Effects on Job Performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 617–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilmarschaufeli.nl. Available online: https://www.wilmarschaufeli.nl/publications/Schaufeli/Test%20Manuals/Test_manual_UWES_English.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Soane, E.; Truss, C.; Alfes, K.; Shantz, A.; Rees, C.; Gatenby, M. Development and Application of a New Measure of Employee Engagement: The ISA Engagement Scale. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2012, 15, 529–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Engageforsuccess.org. Available online: https://engageforsuccess.org/practical-tools-and-resources/the-isa-engagement-scale (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Gallup.com. Available online: https://www.gallup.com/learning/310535/hr-learning-and-development.aspx (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Researchgate.net. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Chandra-Sekhar-Patro/publication/281967834_The_Impact_of_Employee_Engagement_on_Organization’s_Productivity/links/55ffe1bd08aec948c4f9c08a/The-Impact-of-Employee-Engagement-on-Organizations-Productivity.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2022).

- Turner, P. Employee Engagement in Contemporary Organizations: Maintaining High Productivity and Sustained Competitiveness; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dandona, A. Employee Engagement: Maximising Organisational Performance. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2016, 5, 266–280. [Google Scholar]

- Florida, R. Narodziny Klasy Kreatywnej; Narodowe Centrum Kultury: Warszawa, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Florida, R. Cities and the Creative Class; American Sociological Assiociation: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Inglehart, R.; Welzel, C. Modernization, Cultural Change and Democracy; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pewresearch.org. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2020/05/14/on-the-cusp-of-adulthood-and-facing-an-uncertain-future-what-we-know-about-gen-z-so-far-2/#:~:text=Members%20of%20Gen%20Z%20are,as%20it%20existed%20before%20smartphones (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Deloitte.com. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/pages/consumer-business/articles/understanding-generation-z-in-the-workplace.html (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Poradnikprzedsiebiorcy.pl. Available online: https://poradnikprzedsiebiorcy.pl/-pokolenia-w-pracy-baby-boomers (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Haufe.de. Available online: https://www.haufe.de/personal/hr-management/studie-wuensche-und-beduerfnisse-der-generation-z-im-job_80_547736.html (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Gallup.com. Available online: https://www.gallup.com/workplace/351545/great-resignation-really-great-discontent.aspx (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Forbes.com. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/lisacurtis/2021/06/30/why-the-big-quit-is-happening-and-why-every-boss-should-embrace-it/ (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Bankrate.com. Available online: https://www.bankrate.com/personal-finance/job-seekers-survey-august-2021/ (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Recruiting.xing.com. Available online: https://recruiting.xing.com/de/wissen-veranstaltungen/wissen/hr-news-trends/studie-von-xing-e-recruiting-2022 (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Pewresearch.org. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2022/03/09/majority-of-workers-who-quit-a-job-in-2021-cite-low-pay-no-opportunities-for-advancement-feeling-disrespected/m (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Mckinsey.com. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/business%20functions/people%20and%20organizational%20performance/our%20insights/great%20attrition%20or%20great%20attraction%20the%20choice%20is%20yours/great-attrition-or-great-attraction-the-choice-is-yours-vf.pdf?shouldIndex=false (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Kochmańska, A. Innovative, intangible ways of motivating employees in modern enterprises in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic, Innovation management and information technology impact on global economy in the era of pandemic. In Proceedings of the 37th International Business Information Management Association Conference (IBIMA), Cordoba, Spain, 30–31 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Scholte, J.A. Globalizacja; Humanitas: Sosnowiec, Poland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cunniah, D. (Ed.) From Precarious Work to Decent Work: Outcome Document to the Workers’ Symposium on Policies and Regulations to Combat Precarious Employment; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rąb, K.; Rąb, Ł. Precariat and precarious work as negative factors conditioning sustainable development. Zesz. Nauk. Organ. I Zarządzanie 2015, 81, 167–174. [Google Scholar]

- Rąb, Ł.; Kettler, K. Perspective of sustainable development in post-pandemic world: Surveillance capitalism and hopes. Soc. Regist. 2020, 4, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strikemag.org. Available online: strikemag.org/bullshit-jobs (accessed on 11 March 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kuzior, A.; Kettler, K.; Rąb, Ł. Great Resignation—Ethical, Cultural, Relational, and Personal Dimensions of Generation Y and Z Employees’ Engagement. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6764. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116764

Kuzior A, Kettler K, Rąb Ł. Great Resignation—Ethical, Cultural, Relational, and Personal Dimensions of Generation Y and Z Employees’ Engagement. Sustainability. 2022; 14(11):6764. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116764

Chicago/Turabian StyleKuzior, Aleksandra, Karolina Kettler, and Łukasz Rąb. 2022. "Great Resignation—Ethical, Cultural, Relational, and Personal Dimensions of Generation Y and Z Employees’ Engagement" Sustainability 14, no. 11: 6764. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116764

APA StyleKuzior, A., Kettler, K., & Rąb, Ł. (2022). Great Resignation—Ethical, Cultural, Relational, and Personal Dimensions of Generation Y and Z Employees’ Engagement. Sustainability, 14(11), 6764. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116764