The Rural Livability Evaluation and Its Governance Path Based on the Left-Behind Perspective: Evidence from the Oasis Area of the Hexi Corridor in China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background

1.2. The Current Situation of the Left-Behind Population in China

2. Theoretical Analysis

3. Overview of the Study Area

3.1. Overview of Physical Geography

3.2. Socioeconomic Overview

4. Research Methods and Data Sources

4.1. Data Sources

4.2. Research Methods

4.2.1. Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA)

4.2.2. Identification Method of Left-Behind Village Types

4.2.3. The Livability Evaluation for the Elderly, Women, and Children

- 1.

- The Construction of the Evaluation Index System

- 2.

- Data Standardization

- 3.

- Entropy Method

4.2.4. The Evaluation of Comprehensive Livability

4.3. The Classification of Village Governance Types

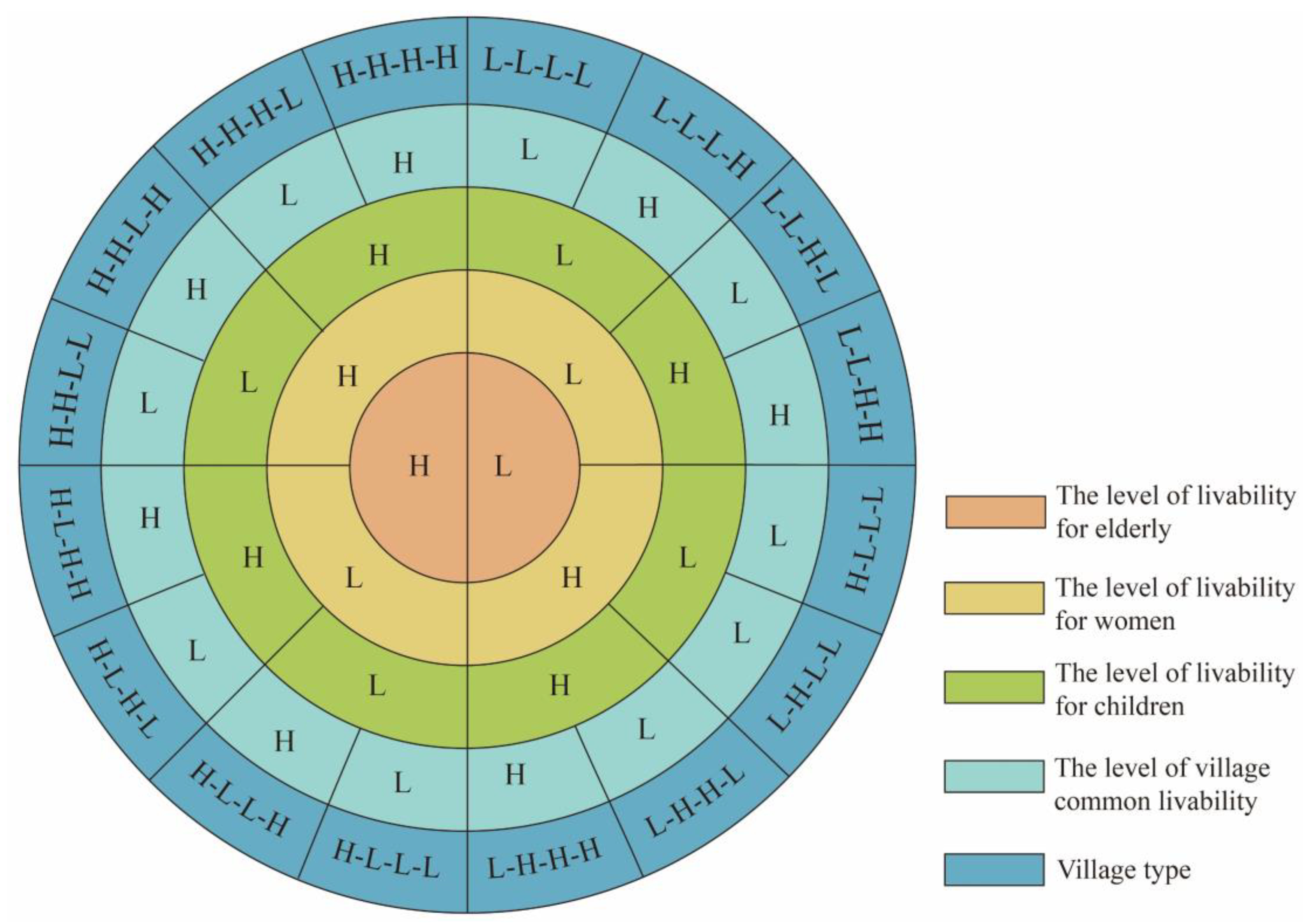

5. Result Analysis

5.1. Identification of Left-Behind Village Types

5.2. Evaluation of the Livability of the Village

5.2.1. Individual Livability

5.2.2. Comprehensive Livability Level

5.3. Classification of Governance Types in Villages

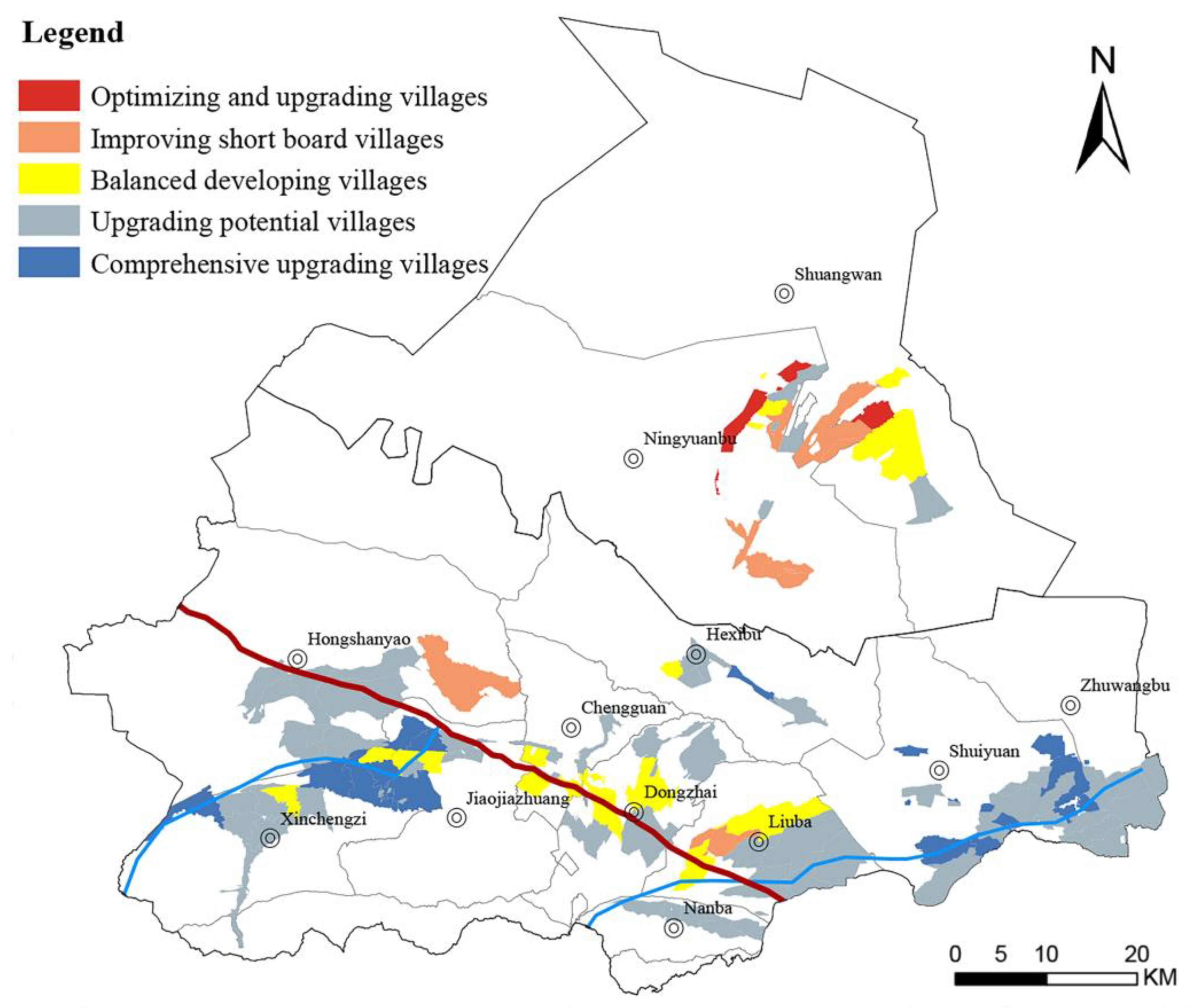

- Optimizing and upgrading villages: This type is mainly H-H-H-H type villages. The livability for the elderly, women, and children as well as common livability are all at a high level. The village has a superior geographical location, a good overall human living environment, complete infrastructure, and a high level of economic development. There were 2 villages of this type, accounting for 2.08% of all left-behind villages: Jinhe village in Shuangwan town and Xipo village in Ningyuanbao town of Jinchuan District.

- Improving short-board village: This type is mainly L-H-H-H, H-L-H-H, H-H-L-H and H-H-H-L type villages. The overall level of livability is high, and the resources and environment are good. Villages with significant shortcomings in the development process can improve the shortcomings in the development of projects and village space efficiency and achieve coordinated development of rural livability. There were 8 villages of this type, accounting for 8.33% of the total number of all left-behind villages. Among them, 75% of the improving short-board villages are in Jinchuan District.

- Balanced developing villages: This type is mainly H-H-L-L, H-L-H-L, H-L-L-H, L-H-H-L, L-H-L-H, and L-L-H-H villages. The levels of livability in these types of villages vary. The government should continue to maintain the advantages, integrate and coordinate other functions, and develop villages in a balanced manner. There were 16 villages of this type, accounting for 16.67% of all left-behind villages, which were scattered throughout the study area.

- Upgrading potential villages: This mainly includes H-L-L-L, L-H-L-L, L-L-H-L, and L-L-L-H type villages. The overall livability level is low. However, the individual livability shows advantages. The livable environment has a certain potential. The number of this type of village was the largest number, reaching 55 in total, accounting for 57.29% of all left-behind villages and accounting for 57.29% of all left-behind villages. Among them, 96.36% of the upgrading potential villages are located in Yongchang County.

- Comprehensive upgrading villages: This type is mainly L-L-L-L type villages. The livability levels for the elderly, women, and children, as well as the common livability levels, are low. The degree of rural subjects’ aging and weakening is high. The hollowing is serious. The economic development is relatively poor. The basic service facilities and public services need to be further comprehensively improved. There were 15 villages of this type, accounting for 15.63% of all left-behind villages. They are located in Yongchang County.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

6.1. Discussion

6.1.1. Rural Livability under the Needs of the Left-Behind Population

6.1.2. Discussion on the Classified Governance Path of Left-Behind Villages

- Optimizing and upgrading village: This type of village has a good economy, complete infrastructure, and public services. These villages are located on the periphery of the urban area. Under the rural revitalization and development model of “leading rural areas with urban areas and promoting agriculture with industry”, the government can promote the complementarity and flow of resources between urban and rural areas and give full play to the trickle-down effect of surrounding towns [21]. This can realize urban-rural integration and rural transformation and upgrading, speed up the process of interconnection and sharing of public services between urban and rural areas, and improve the quality of life of the left-behind population. Villages with rural tourism advantages can actively explore the integrated development of “tourism +” industries under the background of normalized epidemic prevention and control, protect rural characteristic resources, meet the demands of urban and rural residents’ upgraded consumption, build a large-scale, professional, characteristic, and diversified rural tourism industry system, stimulate new vitality in the countryside, and create a village that is livable, recreational, and suitable for business and tourism.

- Improving short-board village: The future development of this type villages focuses on making up for its shortcomings. Left-behind elderly villages can establish a diversified rural elderly care public service mechanism based on government financial subsidies. The government should gradually open up the elderly service market, coordinate social organizations, and innovate a method for elderly care. This can alleviate the problem of insufficient care for the left-behind elderly and guarantee the psychological and physical health of the left-behind elderly. In addition, the government should use the digital cultural stations in Jinchang to promote digital cultural experience services, enrich the spiritual lives of the left-behind population, retain cultural memories and cultural emotions, and improve the mental outlook of villagers. The government should pay attention to the value and potential of left-behind women in rural revitalization. Left-behind women villages can organize female deputies to people’s congresses and cadres of women’s federations to publicize in the villages. This can enhance the enthusiasm of left-behind women in social participation and protect the rights and interests of political participation. Giving full play to the role of women in rural governance can alleviate the conflicts in rural left-behind families and allow left-behind women to reshape their development value in the process of social participation. Left-behind children villages need to improve the education mechanism, with school as the core and the government, family, and village as the support. This can change the educational imbalance between urban and rural areas between regions and between schools.

- Balanced developing villages: The livability evaluation of this type of village is at a medium level. The government can focus on improving the employment rate of rural industries based on village development and resources. The government can focus on developing modern industrial areas along national highways, creating advantageous brands, building information-based and specialized rural industries, enriching jobs, and realizing the employment transformation of left-behind women. Based on traditional agriculture, the government should focus on animal husbandry and plateau vegetables to develop characteristic industries and form an agricultural industry system with planting, breeding, production, supply, and marketing [58]. The government should explore the “Internet + agriculture” model, extend the industrial chain of agricultural products, and promote the process of agricultural network sales.

- Upgrading potential village: This type of village should ensure the allocation and supply of public service facilities, set up a comprehensive supporting system of rural basic public facilities, and optimize the spatial layout of the facilities based on the actual development needs of the left-behind population [59]. This can achieve the goal of equalizing urban and rural public services. Left-behind elderly and left-behind children villages can reorganize rural life circles according to the temporal and spatial behaviors and development needs of the left-behind population [60] and based on changes in village blood, geographical, and professional relationships. Improving the construction of schools and medical facilities can improve the completeness of facilities, provide educational and medical resources to the weak areas, and optimize the spatial layout. Schools can improve the construction of boarding systems to alleviate the problems of poor learning autonomy and the low safety and security of left-behind children. Left-behind women villages can develop rural industries in conjunction with towns and industrial areas to increase opportunities for left-behind women to be employed near home and train their labor skills. This can provide human resources for the development of rural industries, thereby improving the employment environment in rural areas and reducing the burden on left-behind families.

- Comprehensive upgrading villages: This type of village is seriously aging and weakening, and the development vitality is insufficient. Under the background of population exodus, the construction of central villages within the town area can be strengthened in the future. The large-scale, professional, and market-oriented development of the rural economy can be promoted. The spatial structure and resource allocation can be optimized to drive the development of other surrounding villages. Comprehensive upgrading villages should further improve infrastructure, establish and improve basic public services and social security systems that coordinate urban and rural areas, benefit the whole village and urban and rural areas, and improve the quality of life of the left-behind population. This offers medical care for the left-behind elderly and education for left-behind children. The government should increase policy support and provide certain allowances to the left-behind population through the Spring Bud Program and Golden Talent Program.

6.1.3. Shortcomings and Outlook

6.2. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, Y.S.; Long, H.L.; Li, Y.R. Human geography research based on the new thinking of global rural-urban relationship. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2021, 76, 2869–2884. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, L.; Ren, Y.S.; Zhu, D.C.; Cheng, J.M.; Yang, Y.Z.; Yang, Z.; Yao, G.R. The research framework and prospect of rural revitalization led by rural tourism. Geogr. Res. 2019, 38, 102–118. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, X.L.; Yu, S.Y.; Ouyang, Q.L.; Mao, K.B.; He, Y.H.; Zhou, G.H. Assessment and influencing factors of rural hollowing in the rapid urbanization region: A case study of Changsha-Zhuzhou-Xiangtan urban agglomeration. Geogr. Res. 2017, 36, 684–694. [Google Scholar]

- Marjanne, S.; Marc, A. Settlement models, land use and visibility in rural landscapes: Two case studies in Greece. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 80, 362–374. [Google Scholar]

- Doxiadis, C.A. Athropopolis Center. Action for Human Settlements; Athens Publishing: Athens, Greece, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Dahms, F. Settlement evolution in the arena society in the urbanfield. J. Rural Stud. 1998, 14, 299–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casellati, A. The nature of livability. In International Making Cities Livable Conferences; Gondolier Press: California, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Nunt. Cities-engines of rural development. Habitat Debate 2004, 10, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hahlweg, D. The city as a family. In International Making Cities Livable Conferences; Gondolier Press: California, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Palej, A. Architecture for, by and with children: A way to teach livable city. In International Making Cities Livable Conferences; Lennard Institute for Livable Cities: Vienna, Austria, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, A.; Sen, J. Livability assessment within a metropolis based on the impact of integrated urban geographic factors (IUGFs) on clustering urban centers of Kolkata. Cities 2018, 74, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.L. Readings in Rural Settlement Geography; National Geographical Society of India: Varanasi, India, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Mandal, R.B. Introduction to Rural Settlements; Concept Publishing Company: New Delhi, India, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Clocke, P. Rural Settlement Planning; Methuen: London, UK, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, S.M.; Wu, C.C. A special form of urbanization of rural population China comment on the population of both workers and peasants. Acta Geogr. Sin. 1982, 37, 155–163. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, B.; Henry, M.S. Size and growth of urban centers in French labor market areas: Consequences for rural population and employment. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2000, 30, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanbur, R.; Zhang, X. Which Regional Inequality? The Evolution of Rural–Urban and Inland–Coastal Inequality in China from 1983 to 1995. J. Comp. Econ. 1999, 27, 686–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, L.Y. Introduction to Sciences of Human Settlements; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2001; pp. 63–67. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Yu, M. Evaluation and determinants of satisfaction with rural livability in China’s less-developed eastern areas: A case study of Xianju County in Zhejiang Province. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 104, 711–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.R.; Qiao, L.Y.; Wang, Q.Y.; Karácsonyi, D. Towards the evaluation of rural livability in China: Theoretical framework and empirical case study. Habitat Int. 2020, 105, 102241. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W.; Sun, T. Evaluation of rural habitat environment in under-developed areas of Western China: A case study of Northern Shaanxi. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 1573–2975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Q.; Zheng, D.Y. Identification and revitalization of rural poverty-stricken areas in northwest China. Geogr. Res. 2019, 38, 509–521. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, H.; Zhu, Z.; He, Y. Integrated framework of rural landscape research: Based on the global perspective. Landsc. Ecol. 2022, 37, 1572–9761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.B.; Jiang, G.H.; Zhao, Q.L. Geographic identification, spatial differentiation, and formation mechanism of multifunction of rural settlements: A case study of 804 typical villages in Shandong Province, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 166, 1202–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faiz, A.; Faiz, A.; Wang, W.; Bennett, C. Sustainable Rural Roads for Livelihoods and Livability. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 53, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qu, G.B.; Zhao, T.Y.; Zhu, B.W.; Tzeng, G.H.; Huang, S.L. Use of a Modified DANP-mV Model to Improve Quality of Life in Rural Residents: The Empirical Case of Xingshisi Village, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jiang, X.; Wang, L.; Su, X.; Zeng, W.; Xu, A.; Zheng, Q. Spatial heterogeneity in and distributional characteristics of rural ecological livability in China—The case of Fujian Province. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0244238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.Y.; Liu, Y.S. The scientific connotation, formation mechanism and control strategy of “rural disease” in China in the new era. Hum. Geogr. 2018, 33, 100–106. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L.B.; Dou, H.J.; Wu, S.S.; Shi, Z.H.; Li, Z.Y. Rural development pressure and “three-stay” response: A case of Jinchang City in the Hexi Corridor, China. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 91, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, A.P. Research Progresses of Rural Regional-System Degradation. Chin. Agric. Sci. Bull. 2014, 30, 112–116. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, P.; Deller, S. Economic diversity, unemployment and the great recession. Q. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2017, 64, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.B.; Cui, X.J.; Yao, Y. Gradient Difference of Structure of Rural Construction Land in Loess Hilly Region: A Case Study of Yuzhong County, Gansu Province, China. Land 2021, 10, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Liu, Y.S.; Chen, Y.F. Comprehensive measure and partition of rural hollowing in China. Geogr. Res. 2012, 31, 1697–1706. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.S.; Zang, Y.Z.; Yang, Y.Y. China’s rural revitalization and development: Theory, technology and management. J. Geogr. Sci. 2020, 30, 1923–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F. Rural revitalization and rural functional optimization and transformation in China. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2021, 41, 2158–2167. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Q.B.; Ye, J.Y.; Chen, Y.J. The spatial differentiation of rurality in developed coastal regions of eastern China based on rural revitalization: The case of Zhejiang Province. Sci. Geo Graph. Sin. 2022, 42, 466–475. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, H.; Zhang, M.Z.; Liu, J.M. Symbiosis and integration: Coordinated development of human-land-industry in rural heritage sites: A case study of the Tingsong cultural community. Prog. Geogr. 2022, 41, 582–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.H.; Jia, L.R.; Wu, W.H.; Yan, J.Y.; Liu, Y.S. Urbanization for rural sustainability—Rethinking China’s urbanization strategy. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 178, 580–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.F.; Hui, E.C.M.; Zhou, J.M.; Lang, W.; Chen, T.T.; Li, X. Rural Revitalization in China: Land-Use Optimization through the Practice of Place-making. Land Use Policy 2020, 97, 104788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Jiang, Q. Land arrangements for rural–urban migrant workers in China: Findings from Jiangsu Province. Land Use Policy 2016, 50, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.Z. Left-behind population and development experience. J. China Agric. Univ. Soc. Sci. 2011, 28, 5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, J.Z. Studies on Rural Left-behind Population: General Position, Some Misunderstandings and New Theoretical Perspectives. Popul. Res. 2019, 43, 21–31. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, H.; Dong, X.; MacPhail, F. Labor Migration and Time Use Patterns of the Left-behind Children and Elderly in Rural China. World Dev. 2011, 39, 2199–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thissen, F.; Droogleever, F.J. “The village as a coat”; changes in the person-environment fit for older people in a rural area in The Netherlands. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 87, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Dong, W. Can money substitute adult Children’s absence? Measuring remittances’ compensation effect on the health of rural migrants’ left-behind elderly parents. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 79, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.Y.; Zhong, B.; Yao, S.Q. Health-related quality of life and influencing factors among rural left-behind wives in Liuyang, China. BMC Womens Health 2014, 14, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, Q.; Liu, G.; Zang, W. The health of left-behind children in rural China. China Econ. Rev. 2015, 36, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsoum, G. From Fisher wives to fish vendors: Gendered livelihood transitions in a fishing village in Egypt. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 88, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, M.; Zang, L.; Zhang, H. The Effects of Parental Absence on Children Development: Evidence from Left-Behind Children in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Y.; Wang, W.; Li, S.; Zhang, L. The cumulative impact of parental migration on schooling of left-behind children in rural China. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 86, 527–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, F.; Shi, Y.; Shen, A.; Kohrman, A.; Li, K.; Wan, Q.; Rozelle, S. Understanding the Situation of China’s Left-Behind Children: A Mixed-Methods Analysis. Dev. Econ. 2019, 57, 3–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Bian, F.; Zhang, L.; Cao, Y. The Impact of Social Support on the Health of the Rural Elderly in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guo, Y.Z.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y.S. SpatialTemporal Evolution of Rural Population Outflow and Its Mechanism in China. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2020, 40, 50–59. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.R.; Cao, Z.; Long, H.L. Developing Rural Science and Promoting Rural Vitalization: An overview of the Second Forum on Rural Vitalization and Rural Science. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2019, 74, 1482–1486. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, Y. The impact of urban livability on floating population’s residence intention. Urban Dev. Res. 2020, 27, 20–28. [Google Scholar]

- Elshof, H.; Haartsen, T.; van Wissen, L.; Mulder, C. The influence of village attractiveness onflows of movers in a declining rural region. Rural Stud 2017, 56, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tan, Y.T.; Xu, H.; Zhang, X.L. Sustainable urbanization in China: A comprehensive literature review. Cities 2016, 55, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, L.Y. Village type identification and rural revitalization strategy: A case study of Zhangzi County of Shanxi Province. Prog. Geogr. 2019, 38, 1340–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.; Xie, H.; Wang, X.P. The connotation and method of equalization of basic public service facilities in rural areas: Taking Jiangning Street, Jiangning District, Nanjing City as an example. Urban Plan. 2010, 34, 28–33. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; Yang, H.N.; Ji, Z.M.; Yu, L.L. The reorganization mechanism of the life circle of rural residents under the background of rapid urbanization: Based on the case study of Qunyi Community of Kunshan. Geogr. Res. 2019, 38, 119–132. [Google Scholar]

| Variable Types | Variable | Mean Value | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social security | Number of mutual-aid elderly care service facilities owned per capita | 0.22 | 0.38 |

| Number of health rooms per capita | 0.38 | 0.56 | |

| Industrial development | Number of agricultural processing enterprises in the village | 0.54 | 1.04 |

| Number of agricultural enterprises in the village | 0.50 | 0.84 | |

| Number of farm households with business licenses and carrying out leisure agriculture and rural tourism | 0.56 | 1.74 | |

| Number of agricultural households selling agricultural products online | 0.15 | 0.47 | |

| Grassroots administration | Percentage of female cadres among village cadres | 0.25 | 0.13 |

| Village collective economy | Per capita disposable income of rural residents (1. below CNY 3000; 2. CNY 3000–5000; 3. CNY 5000–10,000; 4. CNY 10,000–15,000; 5. CNY 15,000–20,000; 6. CNY 20,000 or more) | 4.58 | 0.73 |

| Per capita income (dividends) received by residents of this village from the village collective | 567.13 | 3455.77 | |

| Infrastructuree | Area of homestead per number of households | 817.10 | 1197.90 |

| Number of village groups with road access per number of village groups in the village | 0.91 | 0.21 | |

| Number of villager groups who have completed toilet renovation per number of villager groups in this village | 0.64 | 0.86 | |

| Number of villager groups connected to natural gas per number of villager groups in the village | 0.05 | 0.22 | |

| Number of villager groups connected to broadband Internet per number of villager groups in the village | 0.92 | 0.23 | |

| Number of farmers’ amateur cultural organizations per capita | 0.39 | 0.75 | |

| Number of library (hall) and cultural stations per capita | 0.31 | 0.37 | |

| The number of sports and fitness venues per capita | 0.38 | 0.67 |

| Target Level | First-Level Indicators | Second-Level Indicators | Direction of Index |

|---|---|---|---|

| Left-behind elderly individual indicators | Pension security | + | |

| Medical health | + | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| Left-behind women individual indicators | Employment environment | + | |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| Social participation | + | ||

| Left-behind children individual indicators | Educational development | − | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| Common indicators | Economic affluence | + | |

| + | |||

| Living conditions | + | ||

| Infrastructure | + | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| Public services | + | ||

| + | |||

| + |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ma, L.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, Z.; Dou, H. The Rural Livability Evaluation and Its Governance Path Based on the Left-Behind Perspective: Evidence from the Oasis Area of the Hexi Corridor in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6714. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116714

Ma L, Zhang Y, Shi Z, Dou H. The Rural Livability Evaluation and Its Governance Path Based on the Left-Behind Perspective: Evidence from the Oasis Area of the Hexi Corridor in China. Sustainability. 2022; 14(11):6714. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116714

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Libang, Yuqing Zhang, Zhihao Shi, and Haojian Dou. 2022. "The Rural Livability Evaluation and Its Governance Path Based on the Left-Behind Perspective: Evidence from the Oasis Area of the Hexi Corridor in China" Sustainability 14, no. 11: 6714. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116714

APA StyleMa, L., Zhang, Y., Shi, Z., & Dou, H. (2022). The Rural Livability Evaluation and Its Governance Path Based on the Left-Behind Perspective: Evidence from the Oasis Area of the Hexi Corridor in China. Sustainability, 14(11), 6714. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116714