A Study–Life Conflict and Its Impact on Tourism and Hospitality Students’ Burnout and Their Employment Aspirations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1. Students’ Working Experience and Study–Life Conflict

2.2. Study–Life Conflict and Students’ Burnout

2.3. Students’ Burnout and Their Employment Aspirations

3. Materials and Methods

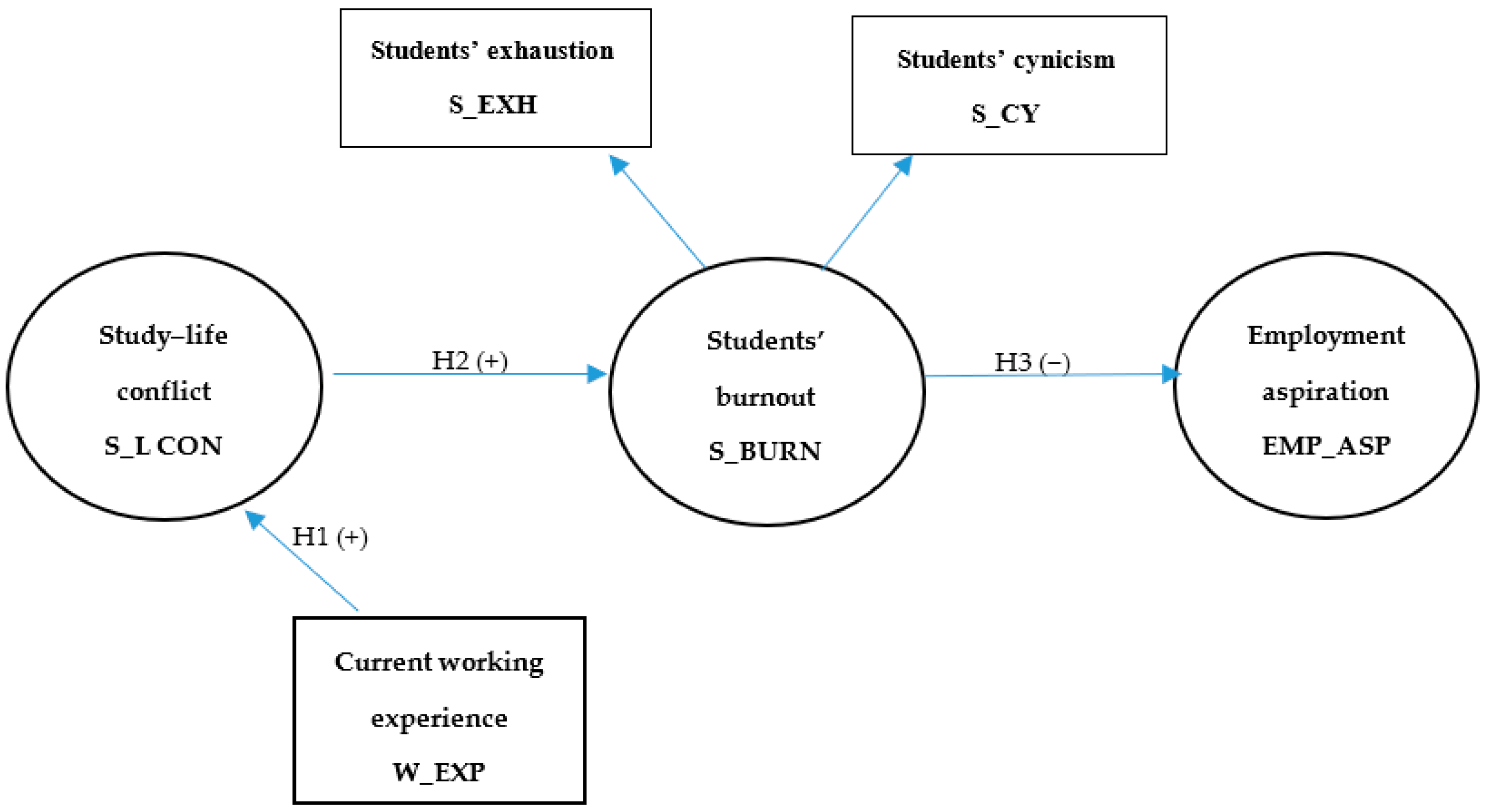

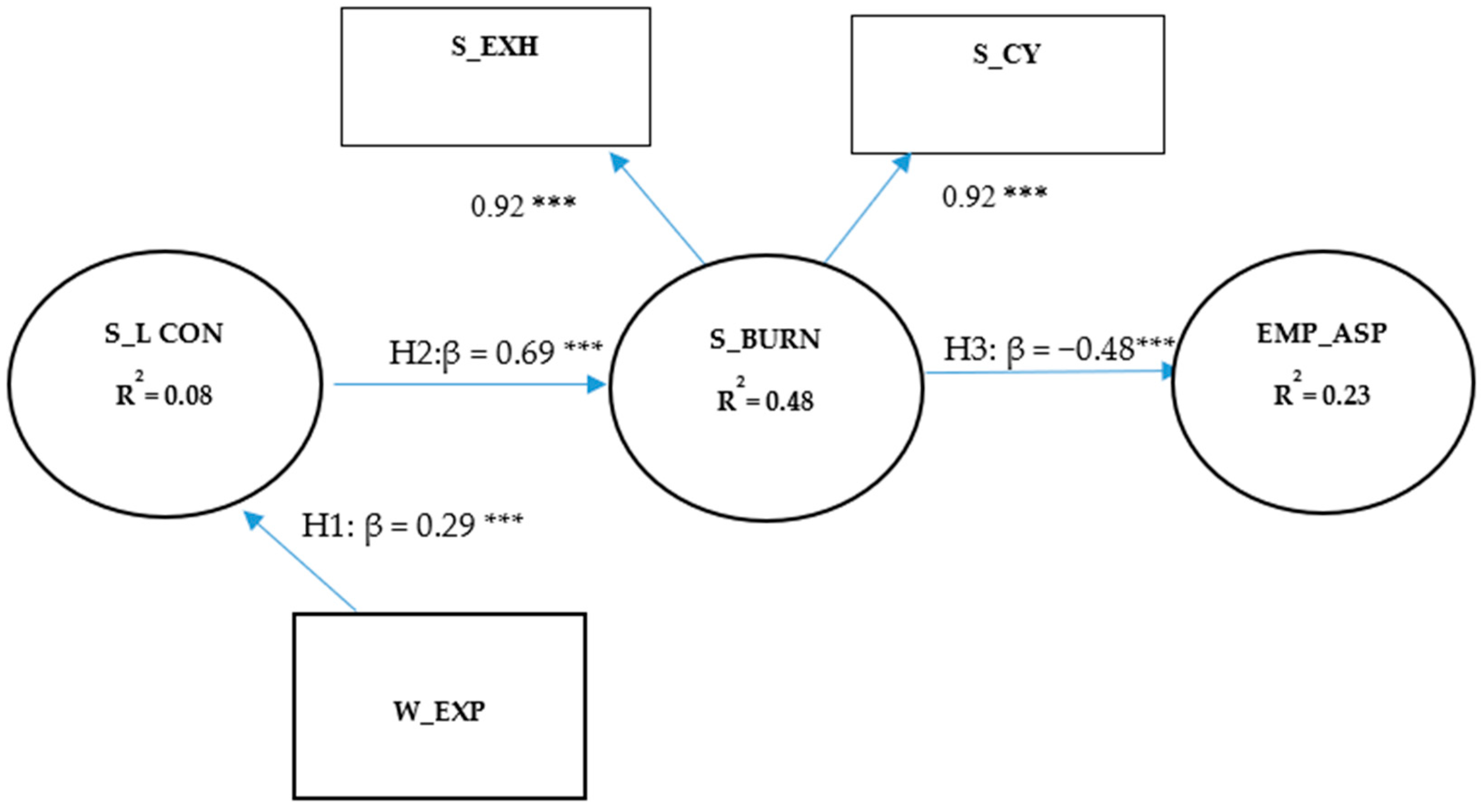

3.1. Research Model

3.2. Data Collection Procedure and Respondents’ Characteristics

3.3. Measures

3.4. Methods

4. Results

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Implications

5.2. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Constructs | Items | |

|---|---|---|

| S_L_CON | The demands of my study interfere with home, family and social life. | |

| Because of my study I cannot involve myself as much as I would like to in maintaining close relations with my family, spouse, or friends. | ||

| Things I want to do at home do not get done because of the demands my study puts on me. | ||

| I often have to miss important family and social activities because of my study. | ||

| There is a conflict between my study and the commitments and responsibilities I have to my family, spouse, or friends. | ||

| EMP_ASP | I would like to work in the field within which I am currently studying. | |

| I believe I can advance my career in the field within which I am currently studying. | ||

| I would recommend the field within which I am currently studying to my friends and relatives. | ||

| It would be a wrong decision to choose the field within which I am currently studying as a career path. | ||

| S_BURN | S_EXH | I feel emotionally drained by my studies. |

| I feel used up at the end of a day at university. | ||

| I feel tired when I get up in the morning and I have to face another day at university. | ||

| Studying or attending a class is really a strain for me. | ||

| I feel burned out from my studies. | ||

| S_CY | I have become less interested in my studies since my enrollment at university. | |

| I have become less enthusiastic about my studies. | ||

| I have become more cynical about the potential usefulness of my studies. | ||

| I doubt the significance of my studies. | ||

References

- Teng, C.C. Developing and evaluating a hospitality skill module for enhancing performance of undergraduate hospitality students. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2013, 13, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, J. Hospitality education in China: A student career-oriented perspective. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2013, 12, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breen, H.; Walo, M.; Dimmock, K. Assessment of tourism and hospitality management competencies: A student perspective. In Proceedings of the New Zealand Tourism and Hospitality Research Conference, Wellington, New Zealand, 8–10 December 2004; pp. 22–34. [Google Scholar]

- Sibanyoni, J.J.; Kleynhans, I.C.; Vibetti, S.P. South African hospitality graduates’ perceptions of employment in the hospitality industry. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2015, 4, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kachniewska, M.; Para, A. Pokolenie Y na turystycznym rynku pracy: Fakty, mity i wyzwania. Rozpr. Nauk. Akad. Wych. Fiz. Wrocławiu 2014, 45, 153–166. [Google Scholar]

- Zagonari, F. Balancing tourism education and training. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glińska-Neweś, A.; Haffer, R.; Wińska, J.; Józefowicz, B. The hospitality world in Poland: A dynamic industry in search of soft skills. In Shapes of Tourism Employment: HRM in the Worlds of Hotels and Air Transport; Grefe, G., Peyrat-Guillard, D., Eds.; Wiley: London, UK, 2020; Volume 4, pp. 77–94. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Z.; Chathoth, P.K. Intern newcomers’ global self-esteem, overall job satisfaction, and choice intention: Person-organization fit as a mediator. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.K.P.; Wong, I.K.A.; Kong, W.H. Student career prospect and industry commitment: The roles of industry attitude, perceived social status, and salary expectations. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- El-Houshy, S.S. Hospitality Students’ Perceptions towards Working in Hotels: A case study of the faculty of tourism and hotels in Alexandria University. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1807.09660. [Google Scholar]

- Roney, S.A.; Öztin, P. Career Perceptions of Undergraduate Tourism Students: A Case Study in Turkey. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2007, 6, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.Y.; Adler, H. Career Goals and Expectations of Hospitality and Tourism Students in China. J. Teach. Travel Tour. 2009, 9, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksu, A.A.; Köksal, C.D. Perceptions and attitudes of tourism students in Turkey. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2005, 17, 436–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, C.C. The effect of personality traits and attitudes on student uptake in hospitality employment. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2008, 27, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Tribe, J. Tourism jobs—Short-lived professions: Student attitudes towards tourism careers in China. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2009, 8, 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Grobelna, A.; Dolot, A. The Role of Work Experience in Studying and Career Development in Tourism: A Case Study of Tourism and Hospitality Students from Northern Poland. Entrep. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2018, 6, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendergast, D. Getting to know the Y Generation. In Tourism and Generation Y; Benckendorff, P., Moscardo, G., Pendergast, D., Eds.; CAB International: Oxfordshire, UK, 2010; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Grobelna, A.; Tokarz-Kocik, A. Potential consequences of working and studying tourism and hospitality: The case of students’ burnout. In Proceedings of the 36th International Scientific Conference on Economic and Social Development, Belgrade, Serbia, 25–26 May 2018; pp. 674–685. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, T.; Ching, L. An exploratory study of an internship program: The case of Hong Kong students. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2007, 26, 336–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusluvan, S.; Kusluvan, Z. Perceptions and attitudes of undergraduate tourism students towards working in the tourism and hospitality industry in a developing economy. In Managing Employee Attitudes and Behaviors in the Tourism and Hospitality Industry; Kusluvan, S., Ed.; Nova Publisher: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 77–98. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, L. Work motivation, job burnout, and employment aspiration in hospitality and tourism students—An exploration using the self-determination theory. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2013, 13, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, S.; Butler, G. Attitudes of Malaysian Tourism and Hospitality Students’ towards a Career in the Industry. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2012, 17, 262–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, S. Tourism and Hospitality Students’ Perceptions of a Career in the Industry: A Comparison of Domestic (Australian) Students and International Students Studying in Australia. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2010, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, S.; Thomas, N.J. Utilising Generation Y: United States Hospitality and Tourism Students’ Perceptions of Careers in the Industry. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2012, 19, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, A.; Jha, B. Industrial Training and Its Consequences on the Career Perception—A Study in Context of the Hotel Management Students’ at Jaipur. EPRA Int. J. Econ. Bus. Rev. 2015, 3, 146–152. [Google Scholar]

- Moscardo, G.; Benckendorff, P. Mythbusting: Generation Y and Travel. In Tourism and Generation Y; Benckendorff, P., Moscardo, G., Pendergast, D., Eds.; CAB International: Oxfordshire, UK, 2010; pp. 16–26. [Google Scholar]

- Glover, P. Generation Y’s future tourism demand: Some opportunities and challenges. In Tourism and Generation Y; Benckendorff, P., Moscardo, G., Pendergast, D., Eds.; CAB International: Oxfordshire, UK, 2010; pp. 155–163. [Google Scholar]

- Benckendorff, P.; Moscardo, G. Understating Generation Y Tourists: Managing the Risk and Chnge Associated with a new Emerging Market. In Tourism and Generation Y; Benckendorff, P., Moscardo, G., Pendergast, D., Eds.; CAB International: Oxfordshire, UK, 2010; pp. 38–46. [Google Scholar]

- Solnet, D.; Hood, A. Generation Y as hospitality employees: Framing a research agenda. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2008, 15, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, H.-K. The Generation Y’s Working Encounter: A Comparative Study of Hong Kong and other Chinese Cities. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2012, 33, 231–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, G.; Cater, C.; Lee, Y.-S.; Ollenburg, C.; Ayling, A.; Lunny, B. Generation Y: Perspectives of quality in youth adventure travel experiences in an Australian backpacker context. In Tourism and Generation Y; Benckendorff, P., Moscardo, G., Pendergast, D., Eds.; CAB International: Oxfordshire, UK, 2010; pp. 58–72. [Google Scholar]

- Grobelna, A.; Wyszkowska-Wróbel, E.M. Understanding Employment Aspirations of Future Tourism and Hospitality Workforce: The Critical Role of Cultural Participation and Study Engagement. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2021, 24, 1312–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coetzee, M. Oosthuizen Students’ Sense of Coherence, Study Engagement and Self-Efficacy in Relation to their Study and Employability Satisfaction. J. Psychol. Afr. 2012, 22, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zopiatis, A.; Theocharous, A.L. Revisiting hospitality internship practices: A holistic investigation. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2013, 13, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uludağ, O.; Yaratan, H. The effect of burnout on engagement: An empirical study on tourism students. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2010, 9, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jogaratnam, G.; Buchanan, P. Balancing the demands of school and work: Stress and employed hospitality students. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2004, 16, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amstad, F.T.; Semmer, N.K. Recovery and the work–family interface. In Current Perspectives on Job-Stress Recovery Research in Occupational Stress and Well-Being; Sonnentag, S., Perrewé, P.L., Ganster, D.C., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2009; Volume 7, pp. 125–166. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Guan, H.; Li, Y.; Xing, C.; Rui, B. Academic burnout and professional self-concept of nursing students: A cross sectional study. Nurse Educ. Today 2019, 77, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, H.; Shin, H.; Lee, S.M. Developmental process of academic burnout among Korean middle school students. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2013, 28, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Beutell, N.J. Sources of Conflict between Work and Family Roles. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1985, 10, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellavia, G.M.; Frone, M.R. Work–family conflict. In Handbook of Work Stress; Barling, J., Kelloway, E.K., Frone, M.R., Eds.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005; pp. 113–148. [Google Scholar]

- Casper, W.J.; Harris, C.H.; Taylor-Bianco, A.; Wayne, J.H. Work–family conflict, perceived supervisor support and organizational commitment among Brazilian professionals. J. Vocat. Behav. 2011, 79, 640–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, F.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, J. Work–Family Conflict, Emotional Responses, Workplace Deviance, and Well-Being among Construction Professionals: A Sequential Mediation Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Netemeyer, R.G.; Boles, J.S.; McMurrian, R. Development and Validation of Work-family Conflict and Family-work Conflict Scales. J. Appl. Psychol. 1996, 81, 400–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, P. Hospitality and Tourism Students’ Part-time Employment: Patterns, Benefits and Recognition. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2007, 6, 40–54. [Google Scholar]

- Barron, P.; Anastasiadou, C. Student part-time employment: Implications, challenges and opportunities for higher education. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 21, 140–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles-Pauvers, B. Employee Turnover: HRM Challenges to Develop Commitment and Job Satisfaction. In Shapes of Tourism Employment: HRM in the Worlds of Hotels and Air Transpor; Grefe, G., Peyrat-Guillard, D., Eds.; Wiley: London, UK, 2020; Volume 4, pp. 55–66. [Google Scholar]

- Karatepe, O.M.; Kilic, H. Relationships of Supervisor Support and Conflicts in the Work-family Interface with the Selected Job Outcomes of Frontline Employees. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 238–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusluvan, S. (Ed.) Characteristics of employment and human resource management in the tourism and hospitality industry. In Managing Employee Attitudes and Behaviors in the Tourism and Hospitality Industry; Nova Publisher: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Grobelna, A.; Marciszewska, B. Undergraduate students’ attitudes towards their future jobs in the tourism sector: Challenges facing educators and business. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Management, Leadership and Governance, St. Petersburg, Russia, 14–15 April 2016; pp. 138–145. [Google Scholar]

- Mannaa, M.; Abou-Shouk, M. Students’ Perceptions towards Working in the Tourism and Hospitality Industry in United Arab Emirates. Al-Adab. J. 2020, 1, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 25, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shreffler, J.; Huecker, M.; Martin, L.; Sawning, S.; The, S.B.; Shaw, M.A.; Olivia Mittel, O.; Holthouser, A. Strategies to Combat Burnout During Intense Studying: Utilization of Medical Student Feedback to Alleviate Burnout in Preparation for a High Stakes Examination. Health Prof. Educ. 2020, 6, 334–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walburg, V. Burnout among high school students: A literature review. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2014, 42, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-F.; Chen, S.-C. Burnout and work engagement among cabin crew: Antecedents and consequences. Int. J. Aviat. Psychol. 2012, 22, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-F.; Kao, Y.-L. Investigating the antecedents and consequences of burnout and isolation among flight attendants. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 868–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, K.H.; Baker, M.A.; Murrmann, S.K. When we are onstage, we smile: The effects of emotional labor on employee work outcomes. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 906–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grobelna, A. Emotional exhaustion and its consequences for hotel service quality: The critical role of workload and supervisor support. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2021, 30, 395–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Shin, K.H.; Swanger, N. Burnout and engagement: A comparative analysis using the big five personality dimension. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-S.; Huang, W.-S.; Yang, C.h.-T.; Chiang, M.-J. Work–leisure conflict and its associations with well-being: The roles of social support, leisure participation and job burnout. Tour. Manag. 2014, 45, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, S.; Tremblay, D.-G. How the need for “leisure benefit systems” as a “resource passageways” moderates the effect of work-leisure conflict on job burnout and intention to leave: A study in the hotel industry in Quebec. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2016, 27, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.-J. Factors affecting student burnout and academic achievement in multiple enrollment programs in Taiwan’s technical–vocational colleges. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2004, 24, 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Martinez, I.; Marques-Pinto, A.; Salanova, M.; Bakker, A. Burnout and engagement in university students. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2002, 33, 464–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2002, 6, 307–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The Job Demands–Resources Model of Burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cazan, A.-M.; Nästasä, L.E. Emotional intelligence, satisfaction with life and burnout among university students. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 180, 1574–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, P.; Maxwell, G.; Broadbridge, A.; Ogden, S. Careers in Hospitality Management: Generation Y’s Experiences and Perceptions. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2007, 14, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grobelna, A.; Tokarz-Kocik, A. Person—Job Fit in Students’ Perspective and Its Consequences for Career Aspirations. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2021, 24, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.M.A.; Baharun, N.; Wazir, N.M.; Ngelambong, A.A.; Ali, N.M.; Ghazali, N.; Tarmazig, S.A.A. Graduates’ Perception on the Factors Affecting Commitment to Pursue Career in the Hospitality Industry. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 224, 416–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, H.; Wang, S.; Fu, X. Meeting career expectation: Can it enhance job satisfaction of Generation Y? Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 27, 147–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koc, E.; Yumusak, S.; Ulukoy, M.; Kilic, R.; Toptas, A. Are internships programs encouraging or discouraging? A viewpoint of tourism and hospitality students in Turkey. J. Hosp. Leis. Sports Tour. Educ. 2014, 15, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltescu, C.A. Graduates’ Willingness to Build a Career in Tourism. A View Point of the Students in the Tourism Profile Academic Programmes from The Transilvania University of Brasov; Annals Economy Series; Faculty of Economics, Constantin Brancusi University: Târgu Jiu, Romania, 2016; Volume 3, pp. 36–39. [Google Scholar]

- Grobelna, A.; Marciszewska, B. Work motivation of tourism and hospitality students: Implications for human resource management. In Proceedings of the 8th European Conference on Intellectual Capital, Venice, Italy, 12–13 May 2016; pp. 95–103. [Google Scholar]

- Wrona, A. Trójmiejski Rynek Pracy. Czym Wygrywamy z Innymi Miastami? 2018. Available online: https://praca.trojmiasto.pl/Trojmiejski-rynek-pracy-Czym-wygrywamy-zinnymi-miastami-n120450.html (accessed on 14 March 2022).

- Gray, P.S.; Williamson, J.B.; Karp, D.A.; Dalphin, J.R. The Research Imagination. In An Introduction to Qualitative and Quantitative Methods; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Boles, J.S.; Howard, W.G.; Donofrio, H.H. An Investigation into the Inter-relationships of Work-family Conflict, Family-work Conflict and Work Satisfaction. J. Manag. Issues 2001, 13, 376–390. [Google Scholar]

- Min, H.; Kim, H.J.; Lee, S.-B. Extending the challenge–hindrance stressor framework: The role of psychological capital. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 50, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.; Puig, A.; Lee, J.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, S.M. Cultural validation of the Maslach Burnout Inventory for Korean students. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2011, 12, 633–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garson, G.D. Partial Least Squares: Regression & Structural Equation Models; Statistical Associates Publishing: Fullerton, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kock, N. WarpPLS User Manual: Version 6.0. 2017. Available online: http://cits.tamiu.edu/WarpPLS/UserManual_v_6_0.pdf#page=77 (accessed on 24 January 2022).

- Vinzi, V.E.; Trinchera, L.; Amato, S. Handbook of Partial Least Squares; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kock, N.; Mayfield, M.P. LS-based SEM Algorithms: The Good Neighbor Assumption, Collinearity, and Nonlinearity. Inf. Manag. Bus. Rev. 2015, 7, 113–130. [Google Scholar]

- Kock, N. Using WarpPLS in e-Collaboration Studies: Mediating Effects, Control and Second Order Variables, and Algorithm Choices. Int. J. e-Collab. 2011, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. Stable p-Value Calculation Methods in PLS-SEM; ScriptWarp Systems: Laredo, TX, USA, 2014; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kock, N. Should bootstrapping be used in pls-sem? Toward stable p-value calculation methods. J. Appl. Struct. Equ. Modeling 2018, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Entrena, M.; Schube, F., 3rd; Gelhard, C. Assessing statistical differences between parameters estimates in Partial Least Squares path modeling. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kock, N. Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. Int. J. e-Collab. 2015, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N.; Lynn, G.S. Lateral Collinearity and Misleading Results in Variance-Based SEM: An Illustration and Recommendations. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2012, 13, 546–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. Using WarpPLS in E-collaboration Studies: An Overview of Five Main Analysis Steps. Int. J. e-Collab. 2010, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. WarpPLS User Manual: Version 7.0; ScriptWarp Systems: Laredo, TX, USA, 2021; Available online: http://www.scriptwarp.com/warppls/UserManual_v_7_0.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2022).

- Pearl, J. Causality: Models, Reasoning and Inference, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kock, N.; Gaskins, L. Simpson’s paradox, moderation, and the emergence of quadratic relationships in path models: An information systems illustration. Int. J. Appl. Nonlinear Sci. 2016, 2, 200–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, C.-F.; Hsieh, T.-S. The impacts of perceived organizational support and psychological empowerment on job performance: The mediating effects of organizational citizenship behavior. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. Specification, Evaluation, and Interpretation of Structural Equation Models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 8–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed.; McGraw–Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.H.J.; Ok, C. Reducing burnout and enhancing job satisfaction: Critical role of hotel employees’ emotional intelligence and emotional labor. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 1101–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.H.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, S.; Hermann, B.; Muheim, F.; Beck, J.; Holsboer-Trachsler, E. Sleep Patterns, Work, and Strain among Young Students in Hospitality and Tourism. Ind. Health 2008, 46, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Robinson, R.N.; Ruhanen, L.; Breakey, N.M. Tourism and hospitality internships: Influences on student career aspirations. Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 19, 513–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grobelna, A. Effects of individual and job characteristics on hotel contact employees’ work engagement and their performance outcomes: A case study from Poland. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 349–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Ramkissoon, H. Structural Equation Modelling and Regression Analysis in Tourism Research. Curr. Issues Tour. 2012, 15, 777–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, B.; McKercher, B.; Waryszak, R. A Comparative Study of Hospitality and Tourism Graduates in Australia and Hong Kong. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2003, 5, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervera-Taulet, A.; Ruiz-Molina, M.-E. Tourism education: A strategic analysis model. J. Hosp. Leis. Sports Tour. Educ. 2008, 7, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nain, A. A study on major challenges faced by hotel industry globally. Int. J. Creat. Res. Thoughts 2018, 6, 561–571. [Google Scholar]

- Haldorai, K.; Kim, W.G.; Pillai, S.G.; Park, T.E.; Balasubramanian, K. Factors affecting hotel employees’ attrition and turnover: Application of pull-push-mooring framework. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 83, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, I.A.; Wan, Y.K.P.; Gao, J.H. How to attract and retain Generation Y employees? An exploration of career choice and the meaning of work. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 23, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Lu, A.C.C.; Gursoy, D.; Neale, N.R. Work engagement, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions: A comparison between supervisors and line-level employees. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 737–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, E.A.; Nicholas, J.; Thomas, N.J.; Bosselman, R.H. Are they leaving or staying: A qualitative analysis of turnover issues for Generation Y hospitality employees with a hospitality education. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 46, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Study-Life Balance, University of Worcester. Available online: https://www.worcester.ac.uk/life/prepare-for-study/study-life-balance.aspx (accessed on 13 March 2022).

- Tromp, D.M.; Blomme, R.J. The Effect of Effort Expenditure, Job Control and Work-home Arrangements on Negative Work-home Interference in the Hospitality Industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 1213–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juaneda, C.; Herranz, R.; Montaño, J.J. Prospective student’s motivations, perceptions and choice factors of a bachelor’s degree in tourism. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2017, 20, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | Fit Coefficients | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Path | AFVIF | 2.28 |

| GoF | 0.46 | |

| SPR | 1.00 | |

| SSR | 1.00 | |

| Measurement | SRMR | 0.12 |

| SMAR | 0.10 | |

| χ2 | 1.28 *** |

| Stage | Measurement | Items | Factor Loadings | t-Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | S_EXH | v1 | 0.74 | 9.47 *** |

| v2 | 0.73 | 9.29 *** | ||

| v3 | 0.84 | 10.96 *** | ||

| v4 | 0.75 | 9.52 *** | ||

| v5 | 0.76 | 9.71 *** | ||

| S_CY | v1 | 0.81 | 10.43 *** | |

| v2 | 0.83 | 10.78 *** | ||

| v3 | 0.84 | 11.01 *** | ||

| v4 | 0.67 | 8.42 *** | ||

| 2 | S_L CON | v1 | 0.82 | 10.69 *** |

| v2 | 0.90 | 11.83 *** | ||

| v3 | 0.82 | 10.57 *** | ||

| v4 | 0.86 | 11.22 *** | ||

| v5 | 0.89 | 11.77 *** | ||

| EMP_ASP | v1 | 0.81 | 10.50 *** | |

| v2 | 0.87 | 11.50 *** | ||

| v3 | 0.72 | 9.14 *** | ||

| v4 | 0.66 | 8.19 *** | ||

| W_EXP | EXP * | 1.00 | 13.59 *** | |

| S_BURN | S_CY | 0.92 | 12.24 *** | |

| S_EXH | 0.92 | 12.23 *** |

| Measure | R2 | ΔR2 | CR | α | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S_LCON | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.93 | 0.91 | 0.73 |

| EMP_ASP | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.85 | 0.77 | 0.60 |

| S_BURN | 0.48 | 0.47 | 0.92 | 0.82 | 0.85 |

| S_EXH * | - | - | 0.87 | 0.81 | 0.63 |

| S_CY * | - | - | 0.88 | 0.83 | 0.59 |

| S_L CON | EMP_ASP | W_EXP | S_BURN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S_L CON | 1 | −0.01 | 0.29 ** | 0.69 *** |

| EMP_ASP | 0.08 *** | 1 | 0 | −0.48 *** |

| W_EXP | - | - | 1 | 0.30 ** |

| S_BURN | 0.70 *** | 0.49 *** | - | 1 |

| Mean | 3.18 | 3.93 | 0.84 | 3.03 |

| Standard deviation | 1.1 | 0.68 | 0.36 | 0.74 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Grobelna, A. A Study–Life Conflict and Its Impact on Tourism and Hospitality Students’ Burnout and Their Employment Aspirations. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6608. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116608

Grobelna A. A Study–Life Conflict and Its Impact on Tourism and Hospitality Students’ Burnout and Their Employment Aspirations. Sustainability. 2022; 14(11):6608. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116608

Chicago/Turabian StyleGrobelna, Aleksandra. 2022. "A Study–Life Conflict and Its Impact on Tourism and Hospitality Students’ Burnout and Their Employment Aspirations" Sustainability 14, no. 11: 6608. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116608

APA StyleGrobelna, A. (2022). A Study–Life Conflict and Its Impact on Tourism and Hospitality Students’ Burnout and Their Employment Aspirations. Sustainability, 14(11), 6608. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116608