Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Teaching ESD: A Theory-Driven Instrument and the Effectiveness of ESD in German Teacher Education

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Self-Efficacy Beliefs

1.2. Requirements for Teaching ESD

- Orientation to Teaching Science:

- ◦

- Beliefs about Purposes of Learning Science, Decision Making in Teaching, Beliefs about the Nature of Science

- Knowledge of Students’ Understanding in Science:

- ◦

- Misconceptions, Learning Difficulties, Need, Motivation & Interest

- Knowledge of Science Curriculum:

- ◦

- Curriculum Materials, Vertical Curriculum, Horizontal Curriculum

- Knowledge of Assessment of Science Learning:

- ◦

- Dimensions of Science Learning to Assess, Methods of Assessing Science Learning

- Knowledge of Instructional Strategies for Teaching Science:

- ◦

- Topic-specific Strategies (Representations, Activities), Subject-specific Strategies

1.3. Previous Instruments for Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Teaching ESD

1.4. Self-Efficacy Beliefs, Self-Rated Content Knowledge, and Teacher Education

1.5. Research Questions and Hypotheses

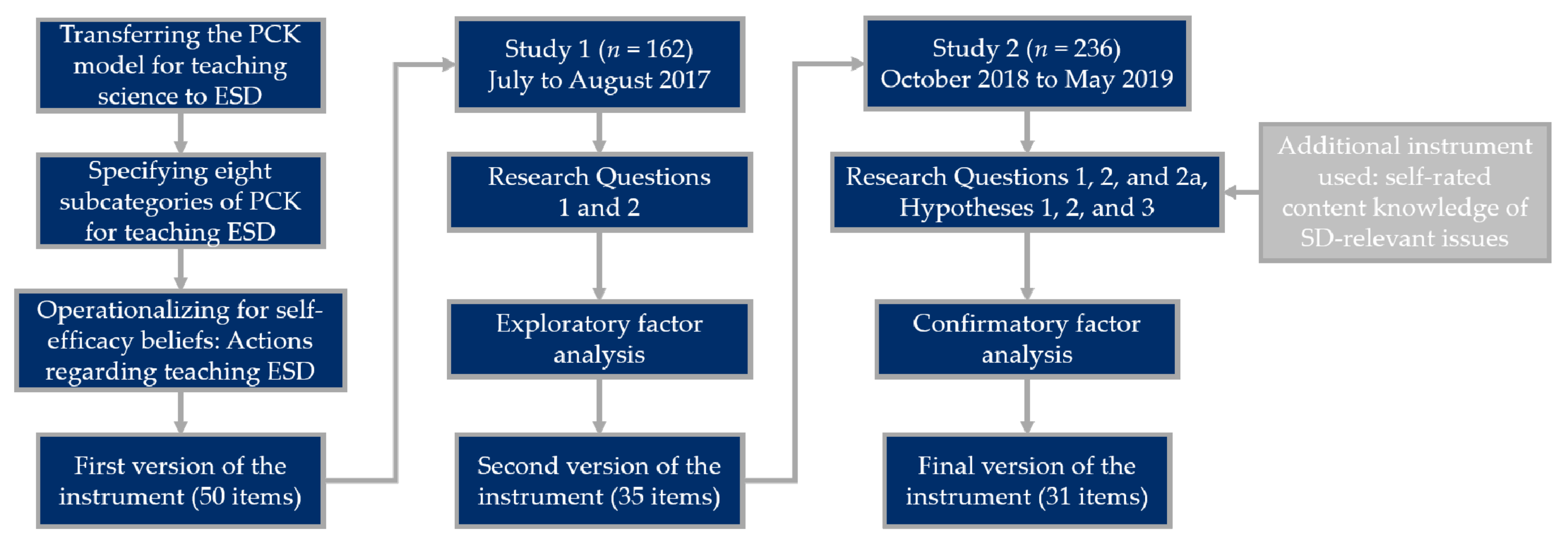

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Instruments

2.2.1. Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Teaching ESD in Secondary Education

2.2.2. Additional Instruments

2.2.3. Procedure

2.3. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Research Question 1: Factorial Structure of the Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Teaching ESD

3.2. Hypothesis 1: Correlation of the ESD-Teaching Self-Efficacy Beliefs with Self-Rated Content Knowledge of SD-Relevant Issues

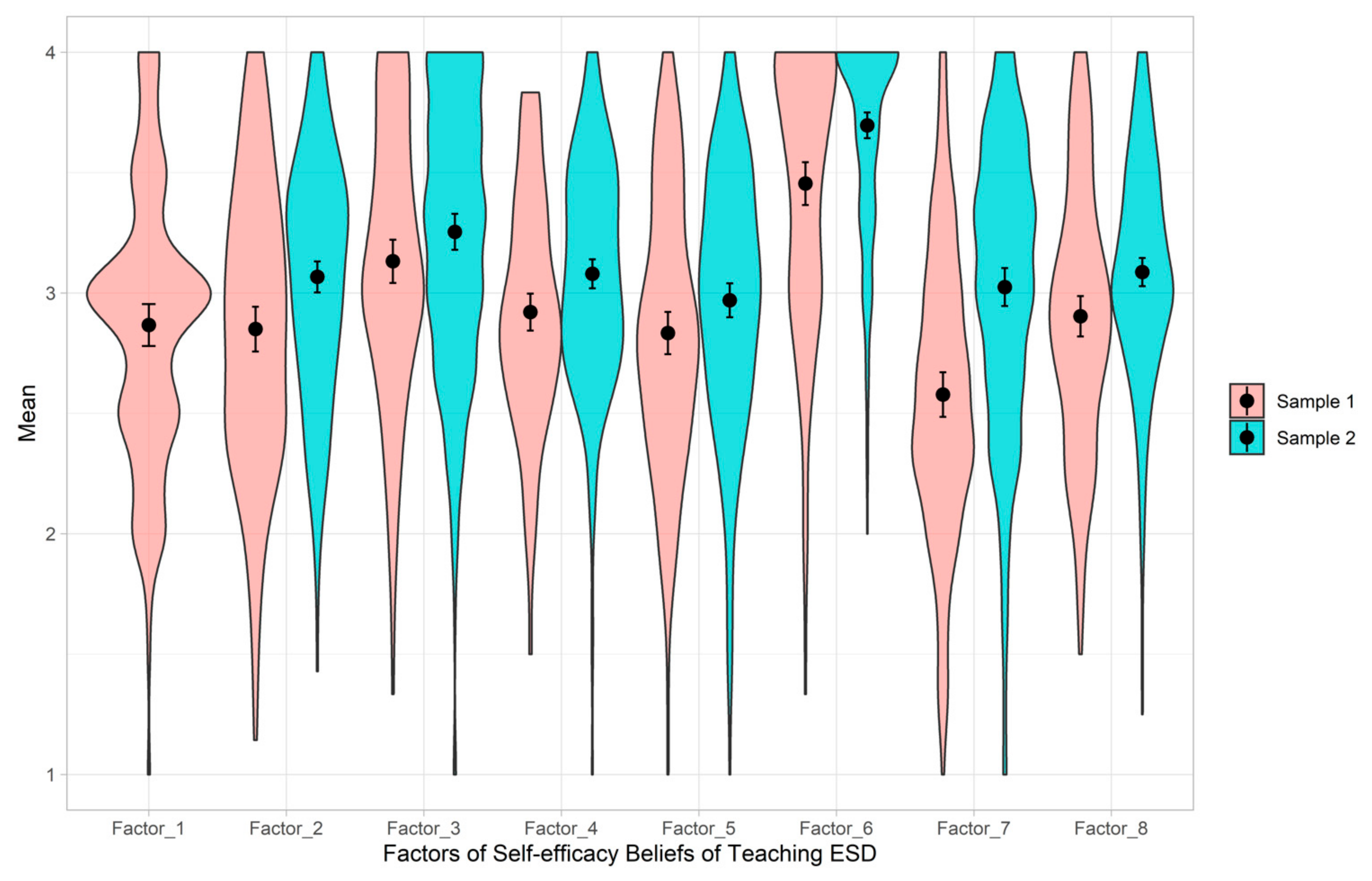

3.3. Research Question 2: Prospective Teachers’ Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Teaching ESD

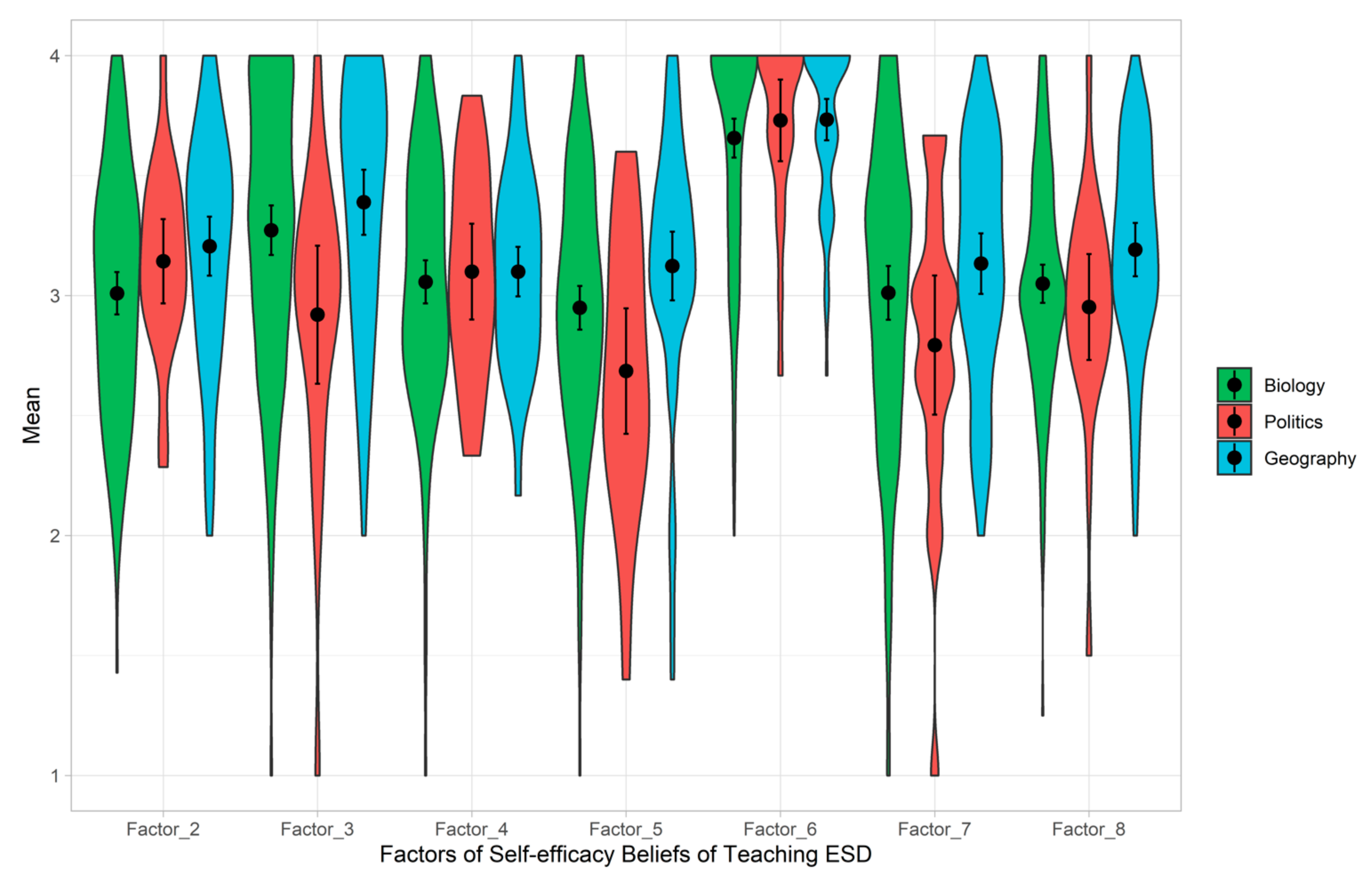

3.4. Research Question 2a: Pre-Service Biology, Politics, and Geography Teachers’ Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Teaching ESD

3.5. Hypothesis 2: Differences between ESD Teaching Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Bachelor and Master of Education Students

3.6. Hypothesis 3: Influence of Currently Participating in at Least One ESD Course on the ESD Teaching Self-Efficacy Beliefs

4. Discussion

4.1. Theory-Driven Instrument of Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Teaching ESD

4.2. First Insights into the Effectiveness of ESD in German Universities

4.3. Limitations

4.4. Future Research

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

We acknowledge support by the Open Access Publication Funds of the Göttingen University (APC funding).

We acknowledge support by the Open Access Publication Funds of the Göttingen University (APC funding).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Leicht, A.; Heiss, J.; Byun, W.J. Introduction. In Issues and Trends in Education for Sustainable Development: Education on the Move; Leicht, A., Heiss, J., Byun, W.J., Eds.; UNESCO Publishing: Paris, France, 2018; pp. 7–16. ISBN 978-92-3-100244-1. [Google Scholar]

- Rieckmann, M. Bildung für nachhaltige Entwicklung im Kontext der Sustainable Development Goals. In Kontroverses Miteinander: Interdisziplinäre und kontroverse Positionen zur Bildung für nachhaltige Entwicklung; Kminek, H., Bank, F., Fuchs, L., Eds.; Frankfurter Beiträge zur Erziehungswissenschaft 23; Goethe-Universität Frankfurt: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2020; pp. 57–85. ISBN 978-3-9820454-8-1. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Learning Objectives. Available online: https://www.unesco.de/sites/default/files/2018-08/unesco_education_for_sustainable_development_goals.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2022).

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Roadmap for Implementing the Global Action Programme on Education for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/1674unescoroadmap.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2022).

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. A/RES/70/1. Available online: https://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/70/1&Lang=E (accessed on 27 April 2022).

- United Nations. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2017. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/files/report/2017/thesustainabledevelopmentgoalsreport2017.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2022).

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). SDG 4—Education 2030: Part II, Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) beyond 2019. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000366797 (accessed on 27 April 2022).

- Sachs, J.D.; Kroll, C.; Lafortune, G.; Fuller, G.; Woelm, F. Sustainable Development Report 2021: The Decade of Action for the Sustainable Development Goals: Includes the SDG Index and Dashboards; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, J.-O.; Bürgener, L.; Barth, M.; Redman, A. Becoming a Competent Teacher in Education for Sustainable Development: Learning Outcomes and Processes in Teacher Education. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2019, 20, 630–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, N.; Stevenson, R.B.; Lasen, M.; Ferreira, J.-A.; Davis, J. Approaches to Embedding Sustainability in Teacher Education: A Synthesis of the Literature. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2017, 63, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Andersson, K.; Jagers, S.C.; Lindskog, A.; Martinsson, J. Learning for the Future? Effects of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) on Teacher Education Students. Sustainability 2013, 5, 5135–5152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moseley, C.; Huss, J.; Utley, J. Assessing K–12 Teachers’ Personal Environmental Education Teaching Efficacy and Outcome Expectancy. Appl. Environ. Educ. Commun. 2010, 9, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moseley, C.; Reinke, K.; Bookout, V. The Effect of Teaching Outdoor Environmental Education on Preservice Teachers’ Attitudes Toward Self-Efficacy and Outcome Expectancy. J. Environ. Educ. 2002, 34, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malandrakis, G.; Papadopoulou, P.; Gavrilakis, C.; Mogias, A. An Education for Sustainable Development Self-Efficacy Scale for Primary Pre-Service Teachers: Construction and Validation. J. Environ. Educ. 2019, 50, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; W.H. Freeman and Company: New York, NY, USA, 1997; ISBN 978-0716728504. [Google Scholar]

- Baumert, J.; Kunter, M. The COACTIV Model of Teachers’ Professional Competence. In Cognitive Activation in the Mathematics Classroom and Professional Competence of Teachers: Results from the COACTIV Project; Kunter, M., Baumert, J., Blum, W., Klusmann, U., Krauss, S., Neubrand, M., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaalvik, E.M.; Skaalvik, S. Teacher Self-Efficacy and Teacher Burnout: A Study of Relations. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2010, 26, 1059–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, J.A. Teacher Efficacy and the Effects of Coaching on Student Achievement. Can. J. Educ. 1992, 17, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Caprara, G.V.; Barbaranelli, C.; Steca, P.; Malone, P.S. Teachers’ Self-Efficacy Beliefs as Determinants of Job Satisfaction and Students’ Academic Achievement: A Study at the School Level. J. Sch. Psychol. 2006, 44, 473–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allinder, R.M. An Examination of the Relationship between Teacher Efficacy and Curriculum-Based Measurement and Student Achievement. Remedial Spec. Educ. 1995, 16, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpe, A.; Czerniak, C.; Haney, J.; Beltyukova, S. Beliefs about Teaching Science: The Relationship between Elementary Teachers’ Participation in Professional Development and Student Achievement. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2012, 34, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschannen-Moran, M.; Hoy, A.W.; Hoy, W.K. Teacher Efficacy: Its Meaning and Measure. Rev. Educ. Res. 1998, 68, 202–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Guide for Constructing Self-Efficacy Scales. In Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Adolescents; Pajares, F., Urdan, T., Eds.; Information Age Publishing: Greenwich, CT, USA, 2006; pp. 307–337. ISBN 978-1-59311-366-7. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer, R.; Jerusalem, M. Das Konzept der Selbstwirksamkeit. In Selbstwirksamkeit und Motivationsprozesse in Bildungsinstitutionen; Jerusalem, M., Hopf, D., Eds.; Zeitschrift für Pädagogik, 44. Beiheft; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 2002; pp. 28–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kultusministerkonferenz. Zur Situation und zu Perspektiven der Bildung für nachhaltige Entwicklung: Bericht der Kultusministerkonferenz vom 17. März 2017. Available online: https://www.kmk.org/fileadmin/Dateien/veroeffentlichungen_beschluesse/2017/2017_03_17-Bericht-BNE-2017.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2022).

- Baumert, J.; Kunter, M.; Blum, W.; Brunner, M.; Voss, T.; Jordan, A.; Klusmann, U.; Krauss, S.; Neubrand, M.; Tsai, Y.-M. Teachers’ Mathematical Knowledge, Cognitive Activation in the Classroom, and Student Progress. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2010, 47, 133–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sadler, P.M.; Sonnert, G.; Coyle, H.P.; Cook-Smith, N.; Miller, J.L. The Influence of Teachers’ Knowledge on Student Learning in Middle School Physical Science Classrooms. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2013, 50, 1020–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Neumann, K.; Kind, V.; Harms, U. Probing the Amalgam: The Relationship between Science Teachers’ Content, Pedagogical and Pedagogical Content Knowledge. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2019, 41, 847–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rosenbaum, S.A. Entwicklung eines Messinstruments zu Selbstwirksamkeitserwartungen angehender Lehrkräfte für das Unterrichten von Bildung für nachhaltige Entwicklung. Master’s Thesis, Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, Göttingen, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.; Chen, Y.-C. Mapping Out the Integration of the Components of Pedagogical Content Knowledge (PCK): Examples From High School Biology Classrooms. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2012, 49, 922–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gess-Newsome, J. A Model of Teacher Professional Knowledge and Skill Including PCK: Results of the Thinking From the PCK Summit. In Re-Examining Pedagogical Content Knowledge in Science Education, 1st ed.; Berry, A., Friedrichsen, P., Loughran, J., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, J.; Daehler, K.R.; Alonzo, A.C.; Barendsen, E.; Berry, A.; Borowski, A.; Carpendale, J.; Chan, K.K.H.; Cooper, R.; Friedrichsen, P.; et al. The Refined Consensus Model of Pedagogical Content Knowledge in Science Education. In Repositioning Pedagogical Content Knowledge in Teachers’ Knowledge for Teaching Science; Hume, A., Cooper, R., Borowski, A., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnusson, S.; Krajcik, J.; Borko, H. Nature, Sources, and Development of Pedagogical Content Knowledge for Science Teaching. In Examining Pedagogical Content Knowledge: The Construct and Its Implications for Science Education, 1st ed.; Gess-Newsome, J., Lederman, N.G., Eds.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1999; pp. 95–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handtke, K.; Bögeholz, S. Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Interdisciplinary Science Teaching (SElf-ST) Instrument: Drafting a Theory-Based Measurement. Educ. Sci. 2019, 9, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Riggs, I.M.; Enochs, L.G. Toward the Development of an Elementary Teacher’s Science Teaching Efficacy Belief Instrument. Sci. Ed. 1990, 74, 625–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enochs, L.G.; Riggs, I.M. Further Development of an Elementary Science Teaching Efficacy Belief Instrument: A Preservice Elementary Scale. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the National Association for Research in Science Teaching, Atlanta, GA, USA, 8–11 April 1990; Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED319601.pdf (accessed on 24 May 2022).

- Sia, A.P. Preservice Elementary Teachers’ Perceived Efficacy in Teaching Environmental Education: A Preliminary Study. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the ECO-ED North American Association for Environmental Education, Toronto, ON, Canada, 20 October 1992; Available online: http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED362487.pdf (accessed on 24 May 2022).

- Moseley, C.; Taylor, B. Analysis of Environmental and General Science Teaching Efficacy Among Instructors with Contrasting Class Ethnicity Distributions: A Four-Dimensional Assessment. Sch. Sci. Math. 2011, 111, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moseley, C.; Utley, J.; Angle, J.; Mwavita, M. Development of the Environmental Education Teaching Efficacy Belief Instrument. Sch. Sci. Math. 2016, 116, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, B.K. Analysis of Environmental and General Science Efficacy among Instructors with Contrasting Class Ethnicity Distributions: A Four Dimensional Assessment. PhD thesis, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, OK, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Dira Smolleck, L.; Zembal-Saul, C.; Yoder, E.P. The Development and Validation of an Instrument to Measure Preservice Teachers’ Self-Efficacy in regard to the Teaching of Science as Inquiry. J. Sci. Teach. Educ. 2006, 17, 137–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinhardt, C. Entwicklung und Validierung eines Testinstruments zu Selbstwirksamkeitserwartungen von (angehenden) Physiklehrkräften in physikdidaktischen Handlungsfeldern; Logos: Berlin, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Effeney, G.; Davis, J. Education for Sustainability: A Case Study of Pre-service Primary Teachers’ Knowledge and Efficacy. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 2013, 38, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boon, H. Beliefs and Education for Sustainability in Rural and Regional Australia. Educ. Rural Aust. 2011, 21, 37–54. Available online: https://researchonline.jcu.edu.au/19339/ (accessed on 24 May 2022).

- Malandrakis, G.; Papadopoulou, P.; Gavrilakis, C.; Mogias, A. Designing and Testing an Education for Sustainable Development Self-Efficacy Scale for Pre-Service Teachers: Preliminary Findings. In Electronic Proceedings of the ESERA 2015 Conference: Science Education Research: Engaging Learners for a Sustainable Future Part 9 (co-ed. M. Achiam, & G. Carvalho); Lavonen, J., Juuti, K., Lampiselkä, J., Uitto, A., Hahl, K., Eds.; University of Helsinki: Helsinki, Finland, 2016; pp. 1280–1288. [Google Scholar]

- Mogias, A.; Malandrakis, G.; Papadopoulou, P.; Gavrilakis, C. Self-Efficacy of In-Service Secondary School Teachers in Relation to Education for Sustainable Development: Preliminary Findings. In Engaging with Contemporary Challenges through Science Education Research: Selected Papers from the ESERA 2019 Conference; Levrini, O., Tasquier, G., Amin, T.G., Branchetti, L., Levin, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleurs, W. (Ed.) Competencies for ESD (Education for Sustainable Development) Teachers: A Framework to Integrate ESD in the Curri-culum of Teacher Training Institutes; CSCT: Brussels, Belgium, 2008; Available online: https://unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/env/esd/inf.meeting.docs/EGonInd/8mtg/CSCT%20Handbook_Extract.pdf (accessed on 24 May 2022).

- Yangin, S.; Sidekli, S. Self-Efficacy for Science Teaching Scale Development: Construct Validation with Elementary School Teachers. J. Educ. Train. Stud. 2016, 4, 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Velthuis, C.; Fisser, P.; Pieters, J. Teacher Training and Pre-Service Primary Teachers’ Self-Efficacy for Science Teaching. J. Sci. Teach. Educ. 2014, 25, 445–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Handtke, K.; Bögeholz, S. Arguments for Construct Validity of the Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Interdisciplinary Science Teaching (SElf-ST) Instrument. Eur. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 9, 1435–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.H.H.; Sillasen, M.K. Missing Concordance between Knowledge and Efficacy among Danish Science Teacher Students regarding Education for Sustainable Development. Nord. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2020, 16, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blonder, R.; Benny, N.; Jones, M.G. Teaching Self-Efficacy of Science Teachers. In The Role of Science Teachers’ Beliefs in International Classrooms: From Teacher Actions to Student Learning; Evans, R., Luft, J., Czerniak, C., Pea, C., Eds.; Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagoly-Simó, P.; Hemmer, I. Bildung für nachhaltige Entwicklung in den Sekundarschulen—Ziele, Einblicke in die Realität, Perspektiven. Available online: http://edoc.ku-eichstaett.de/25373/1/Bagoly-Simo_Hemmer_2017_online_end.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2022).

- Bautista, N.U. Investigating the Use of Vicarious and Mastery Experiences in Influencing Early Childhood Education Majors’ Self-Efficacy Beliefs. J. Sci. Teach. Educ. 2011, 22, 333–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunning, A.M.; Mensah, F.M. Preservice Elementary Teachers’ Development of Self-Efficacy and Confidence to Teach Science: A Case Study. J. Sci. Teach. Educ. 2011, 22, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, N.; Tomas, L.; Woods, C. Impact of Sustainability Pedagogies on Pre-service Teachers’ Self-efficacy. J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 10, 243–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosbrugger, H.; Kelava, A. Qualitätsanforderungen an einen psychologischen Test (Testgütekriterien). In Testtheorie und Fragebogenkonstruktion, 2nd ed.; Moosbrugger, H., Kelava, A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter-Beuschel, L.; Bögeholz, S. Student Teachers’ Knowledge to Enable Problem-Solving for Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2020, 12, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Richter-Beuschel, L.; Bögeholz, S. Knowledge of Student Teachers on Sustainable Land Use Issues–Knowledge Types Relevant for Teacher Education. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Haan, G. The Development of ESD-Related Competencies in Supportive Institutional Frameworks. Int. Rev. Educ. 2010, 56, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Haan, G. Gestaltungskompetenz als Kompetenzkonzept der Bildung für nachhaltige Entwicklung. In Kompetenzen der Bildung für nachhaltige Entwicklung: Operationalisierung, Messung, Rahmenbedingungen, Befunde; Bormann, I., de Haan, G., Eds.; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2008; pp. 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, J.-R.; Siege, H. (Eds.) Orientierungsrahmen für den Lernbereich Globale Entwicklung: Im Rahmen einer Bildung für nachhaltige Entwicklung: Ein Beitrag zum Weltaktionsprogramm „Bildung für nachhaltige Entwicklung; Cornelsen: Berlin, Germany, 2016; Available online: https://www.kmk.org/fileadmin/veroeffentlichungen_beschluesse/2015/2015_06_00-Orientierungsrahmen-Globale-Entwicklung.pdf (accessed on 24 May 2022).

- Niedersächsisches Kultusministerium (Ed.) Kerncurriculum für das Gymnasium Schuljahrgänge 5–10: Naturwissenschaften; Unidruck: Hannover, Germany, 2015; Available online: https://cuvo.nibis.de/cuvo.php?p=download&upload=18 (accessed on 24 May 2022).

- Kultusministerkonferenz. Standards für die Lehrerbildung: Bildungswissenschaften: Beschluss der Kultusministerkonferenz vom 16. Dezember 2004 i. d. F. vom 12. Juni 2014. No longer available online.

- Schulte, K.; Watermann, R.; Bögeholz, S. Überprüfung der faktoriellen Validität einer multidimensionalen Skala der Lehrer-Selbstwirksamkeitserwartung. Empirische Pädagogik 2011, 25, 232–256. [Google Scholar]

- Henson, R.K.; Roberts, J.K. Use of Exploratory Factor Analysis in Published Research: Common Errors and Some Comment on Improved Practice. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2006, 66, 393–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Conway, J.M.; Huffcutt, A.I. A Review and Evaluation of Exploratory Factor Analysis Practices in Organizational Research. Organ. Res. Methods 2003, 6, 147–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabrigar, L.R.; Wegener, D.T.; MacCallum, R.C.; Strahan, E.J. Evaluating the Use of Exploratory Factor Analysis in Psychological Research. Psychol. Methods 1999, 4, 272–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, Y.; Jorgensen, T.D.; Rockwood, N.; Oberski, D.; Byrnes, J.; Vanbrabant, L.; Savalei, V.; Merkle, E.; Hallquist, M.; Rhemtulla, M.; et al. Lavaan: Latent Variable Analysis. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/lavaan/lavaan.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2022).

- Wickham, H.; Chang, W.; Henry, L.; Pedersen, T.L.; Takahashi, K.; Wilke, C.; Woo, K.; Yutani, H.; Dunnington, D. Ggplot2: Create Elegant Data Visualisations Using the Grammar of Graphics. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/ggplot2/ggplot2.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2022).

- Wickham, H.; Girlich, M. Tidyr: Tidy Messy Data. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/tidyr/tidyr.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2022).

- Bühner, M. Einführung in die Test- und Fragebogenkonstruktion, 3rd ed.; Pearson Studium: München, Germany, 2011; ISBN 978-3-8689-4033-6. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics: And Sex and Drugs and Rock ‘n’ Roll, 4th ed.; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-9351500827. [Google Scholar]

- Pospeschill, M. Testtheorie, Testkonstruktion, Testevaluation: Mit 77 Fragen zur Wiederholung; Ernst Reinhardt: München, Germany, 2010; ISBN 978-3825234317. [Google Scholar]

- Guttman, L. Some Necessary Conditions for Common Factor Analysis. Psychometrika 1954, 19, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H.F.; Dickman, K. Analytic Determination of Common Factors. Am. Psychol. 1959, 14, 425–439. [Google Scholar]

- Bortz, J.; Schuster, C. Statistik für Human- und Sozialwissenschaftler; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, T.D. Longitudinal Structural Equation Modeling; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 9781462510160. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.A. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-1-59385-275-7. [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton, B.; Muthén, B.; Alwin, D.F.; Summers, G.F. Assessing Reliability and Stability in Panel Models. Sociol. Methodol. 1977, 8, 84–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diedenhofen, B.; Musch, J. Cocor: A Comprehensive Solution for the Statistical Comparison of Correlations. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0121945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kubinger, K.D.; Rasch, D.; Moder, K. Zur Legende der Voraussetzungen des t-Tests für unabhängige Stichproben. Psychologische Rundschau 2009, 60, 26–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backhaus, K.; Erichson, B.; Plinke, W.; Weiber, R. Multivariate Analysemethoden: Eine anwendungsorientierte Einführung; Springer Gabler: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lünemann, I. Selbstwirksamkeitserwartungen von Lehramtsstudierenden der Fächer Biologie, Erdkunde und Politik zum Unterrichten von Bildung für Nachhaltige Entwicklung. Master’s Thesis, Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, Göttingen, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hartig, J.; Frey, A.; Jude, N. Validität. In Testtheorie und Fragebogenkonstruktion, 2nd ed.; Moosbrugger, H., Kelava, A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 143–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kultusministerkonferenz. Ländergemeinsame inhaltliche Anforderungen für die Fachwissenschaften und Fachdidaktiken in der Lehrerbildung: Beschluss der Kultusministerkonferenz vom 16. Oktober 2008 i.d.F. vom 16. Mai 2019. Available online: https://www.kmk.org/fileadmin/Dateien/veroeffentlichungen_beschluesse/2008/2008_10_16-Fachprofile-Lehrerbildung.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2022).

- Kazempour, M. The Interrelationship of Science Experiences, Beliefs, Attitudes, and Self-Efficacy: A Case Study of a Pre-Service Teacher with Positive Science Attitude and High Science Teaching Self-Efficacy. Eur. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 2013, 1, 106–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settlage, J.; Southerland, S.A.; Smith, L.K.; Ceglie, R. Constructing a Doubt-Free Teaching Self: Self-Efficacy, Teacher Identity, and Science Instruction within Diverse Settings. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2009, 46, 102–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoy, A.W.; Spero, R.B. Changes in Teacher Efficacy during the Early Years of Teaching: A Comparison of Four Measures. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2005, 21, 343–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, C.S. Preservice Teachers’ Expectations about the First Year of Teaching. Teach. Teach. Educ. 1988, 4, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavrikaki, E.; Athanasiou, K. Development and Application of an Instrument to Measure Greek Primary Education Teachers’ Biology Teaching Self-Efficacy Beliefs. Eurasia J. Math. Sci. 2011, 7, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheatley, K.F. The Potential Benefits of Teacher Efficacy Doubts for Educational Reform. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2002, 18, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistisches Bundesamt. Bildung und Kultur: Studierende an Hochschulen: Sommersemester. 2019. Available online: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Bildung-Forschung-Kultur/Hochschulen/Publikationen/Downloads-Hochschulen/studierende-hochschulen-ss-2110410197314.pdf?__blob=publicationFile (accessed on 29 April 2022).

- Eggert, S.; Bögeholz, S.; Oberle, M.; Sauer, M.; Schneider, S.; Surkamp, C. Herausforderung Interdisziplinäres Unterrichten in der Lehrerbildung: Das Göttinger Zertifikatsmodell. J. Lehr. 2018, 18, 51–55. [Google Scholar]

| Author(s), Instrument | Target Group | Based on or Modified from STEBI-A/B | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sia [37] Environmental Education Efficacy Belief Instrument (EEEBI) | Pre-service elementary teachers | x | Two Samples: n = 21 and n = 19 One factor: Personal EE (Environmental Education) Teaching Efficacy Belief Scale 13 Items Measurement: 5-point Likert scale, positive and negative items Analysis: - α = “yet to be determined” (p. 5) |

| Taylor [40]; Moseley & Taylor [38] Environmental and General Science Teacher Efficacy Assessment (EGSTEA) | Sample contains in-service high and middle school science teachers, but the underlying instruments focus more on primary education (EEEBI, STEBI) | x | n = 40 One factor: PTE (personal teacher efficacy) for environmental science 13 Items Measurement: 5-point Likert scale, positive and negative items Analysis: ANOVA α = 0.96 |

| Effeney & Davis [43] according to Boon [44] | Pre-service primary teachers | n = 266 One factor: Self-efficacy for EfS (Education for Sustainability) 4 Items Measurement: 5-point Likert scale, positive and negative items Analysis: Principal Component Analysis (KMO = 0.67, Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity significant, 46% explained variance by two factors) α = 0.71 | |

| Moseley, Utley, Angle & Mwavita [39] Environmental Education Teaching Efficacy Belief Instrument (EETEBI) | Pre-service elementary teachers | x | n = 255 One factor: Personal environmental education teaching efficacy (PEETE) 13 Items Measurement: 6-point Likert scale, positive and negative items Analysis: Principal component analysis (KMO = 0.88, Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity significant, 50.5% explained variance by two factors) α = 0.92 |

| Malandrakis, Papadopoulou, Gavrilakis & Mogias [14,45]; Mogias, Malandrakis, Papadopoulou & Gavrilakis [46] Teachers Self-Efficacy Scale for Education for Sustainable Development (TSESESD) | Pre-service primary (and early childhood) teachers (Tested with secondary in-service teachers without adaptation of the instrument [14,46]) | N (2016) = 305 N (2019) = 924 (804 primary school, 120 early childhood), in addition for validation: 88 in-service primary teachers N (2021) = 267 in-service secondary teachers Four factors:

Measurement: 7-point Likert scale, positive items Analysis: Principal Component Analysis (KMO = 0.96, Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity significant, 72.58% explained variance by four factors) α (2016) = 0.93–0.95, α (2019) = 0.85–0.94, α (2021) = 0.89–0.96 |

| Sample 1 (n = 162) | Sample 2 (n = 236) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Absolute Value | Relative Value | Absolute Value | Relative Value |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 94 | 58.0% | 171 | 72.5% |

| Male | 64 | 39.5% | 61 | 25.8% |

| Federal State | ||||

| Lower Saxony | 110 | 67.9% | 150 | 63.6% |

| Others | 52 | 32.1% | 86 | 36.4% |

| Phase of Teacher Education | ||||

| Bachelor | 78 | 48.1% | 123 | 52.1% |

| Master of Education | 51 | 31.5% | 112 | 47.5% |

| State Examination | 9 | 5.6% | - | - |

| Finished studies | 7 | 4.3% | - | - |

| Type of School | ||||

| Grammar & Comprehensive School | 98 | 60.5% | 236 | 100% |

| Others | 54 | 33.3% | - | - |

| Subject | ||||

| Biology | 44 | 27.2% | 131 | 55.5% |

| Politics | 42 | 25.9% | 21 | 8.9% |

| Geography | 30 | 18.5% | 60 | 25.4% |

| Biology & Politics | 3 | 1.9% | 2 | 0.8% |

| Biology & Geography | 3 | 1.9% | 21 | 8.9% |

| Politics & Geography | - | - | 1 | 0.4% |

| Others | 39 | 24.1% | - | - |

| Number of ESD Courses | Biology (n = 115/120) | Politics (n = 21) | Geography (n = 58) | Biology & Geography (n = 20) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| par | com | par | com | par | com | par | com | |

| 0 | 100 | 66 | 18 | 16 | 21 | 29 | 7 | 7 |

| 1 | 9 | 23 | 3 | 2 | 20 | 9 | 8 | 2 |

| 1.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 4 | 16 | 0 | 2 | 13 | 7 | 4 | 4 |

| 3 | 2 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 0 | 1 |

| 4–6 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| 7–10 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 11–14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Number of ESD Courses | Bachelor (n = 111/113) | Master of Education (n = 106/109) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| par | com | par | com | |

| 0 | 76 | 81 | 72 | 39 |

| 1 | 17 | 10 | 24 | 26 |

| 1.5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 2 | 14 | 11 | 7 | 18 |

| 3 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 17 |

| 4–6 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 7 |

| 7–10 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| 11–14 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Subcategory of PCK (Original) | Subcategory of PCK (Transferred to ESD) |

|---|---|

| Misconception | Learning Difficulties |

| Learning Difficulties | |

| Need | Need |

| Motivation & Interest | |

| Curriculum Materials | Curriculum Materials |

| Vertical Curriculum | Curricular Demands |

| Horizontal Curriculum | |

| Dimensions of Science Learning to Assess | Dimensions of Gestaltungskompetenz to Assess |

| Methods of Assessing Science Learning | Methods of Assessing ESD Learning |

| Subject-specific Strategies | Subject/ESD-specific Strategies and Activities |

| Activities | |

| Representations | Representations |

| Item: “Even in teaching Education for Sustainable Development, I can…” | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1: Fostering Gestaltungskompetenz and Generic Competence (ESD/G) | |||||||||

| 1 | … foster Gestaltungskompetenz 1 cumulatively 2 and systematically 3 over the course of a single teaching unit. 1 Gestaltungskompetenz describes the capability to actively modify and model the society in which one lives in terms of Sustainable Development—taking into account economic, ecological, cultural, and social aspects. The competence area comprises twelve sub-competencies. 2 Being able to connect content over the course of a single and future teaching units. 3 Fostering competencies in a research-based manner by using competence models and methods. | 0.73 | |||||||

| 2 | … foster Gestaltungskompetenz cumulatively 4 and systematically over the course of several school years. 4 Being able to connect content from past and future school years. | 0.63 | |||||||

| 3 | … improve students’ generic 5 competencies cumulatively and systematically over the course of several school years (e.g., problem-solving competence, presentation competence, democracy competence, and social competence). 5 Competencies that are not subject-specific and relevant to all subjects. | 0.48 | −0.25 | ||||||

| 4 | … improve students’ generic competencies cumulatively and systematically over the course of a single teaching unit (e.g., problem-solving competence, presentation competence, democracy competence, and social competence). | 0.45 | 0.26 | ||||||

| Factor 2: Including ESD-specific Instructional Strategies under Consideration of Students’ Motivation (ESD) | |||||||||

| 5 | … integrate cooperative and activating forms of learning to increase self-organized learning (project works, future workshops 6, planning cells 7, Open Space 8). 6 A future workshop is a method in which all participants are experts. The aim is to find solutions to commonly identified problems. For this purpose, three phases are run through: criticism, fantasy, and realization phase (Preußer, 2007b, pp. 3–6). 7 In a planning cell, people representing diverse opinions and interests are brought together at random to develop possible solutions to a given problem (Preußer, 2007b, pp. 3–6). 8 Open Space is a method that enables a discussion process or a creative exchange on a voluntary basis (Preußer, 2007b, pp. 3–6). | 0.69 | |||||||

| 6 | … include planning games (e.g., Water for Ganurbia9, World Climate Conference 9, Climate Change in Court 9). 9 Here, the students take on different roles (representatives from politics, economy, science, and NGOs), deepen unsustainable developments in discussions and develop possible solutions (Preußer, 2007a, pp. 9–12). | 0.68 | |||||||

| 7 | … conceptualize interdisciplinary projects (e.g., biology and art: nature photography exhibition about forests; natural sciences, geography, and German: debate club on the topic “sustainable resource use”). | 0.66 | |||||||

| 8 | … integrate extracurricular partners to include different perspectives in systematic socioscientific decision-making (e.g., experts from politics, the economy, science, and NGOs 10). 10 Non-governmental organizations, such as Greenpeace, Amnesty International. | 0.59 | |||||||

| 9 | … create participation opportunities for students (e.g., by running a student company 11). 11 A student company is a company run by students on their own responsibility. In contrast to a simulation, the students participate in the real market situation (KMK & BMZ, 2016, p. 61). | 0.51 | |||||||

| 10 | … improve students’ motivation by participating in school and society (e.g., organize a school event with the sale of fair-trade products). | 0.47 | |||||||

| 11 | … improve students’ motivation by participating in competitions and campaigns on Sustainable Development (e.g., Transfer-21-Schule 12, Internationale Agenda-21-Schule 12, Umweltschule Europa 12). 12 The “Umweltschule Europa”, “Internationale Agenda-21-Schule”, and “Transfer-21-Schule” awards are conferred to schools for excellent achievements in developing sustainability processes in and outside the school area (BLK, 2005, pp. 13–14). | 0.44 | |||||||

| Factor 3: Using ESD-specific Educational Resources for School (ESD) | |||||||||

| 12 | … use journals and materials for teachers when planning lessons (e.g., Unterricht Biologie, Praxis Geographie). | 0.76 | |||||||

| 13 | … consider textbooks’ materials and tasks (e.g., Projekt G Gesellschaftslehre, Prisma Naturwissenschaften) when planning lessons. | 0.58 | |||||||

| 14 | … integrate current didactical approaches from textbooks of the didactics (e.g., Fachdidaktik Biologie, Geographiedidaktik, Politik-Didaktik). | 0.42 | |||||||

| Factor 4: Surveying Dimensions of Gestaltungskompetenz (ESD) | |||||||||

| 15 | … survey students’ ability to show solidarity, to change perspective, and to empathize with humans and the environment. | 0.70 | |||||||

| 16 | … survey students’ conceptions about justice and sustainability, which legitimize their social and ethical actions. | 0.61 | −0.27 | ||||||

| 17 | … survey students’ willingness to motivate themselves and others for topics of Sustainable Development. | 0.58 | |||||||

| 18 | … survey students’ private, social, and political participation in realizing Sustainable Development Goals. | 0.47 | |||||||

| 19 | … survey students’ critical reflection on their own or foreign value benchmarks in the solution of dilemmatic decision-making situations. | 0.39 | −0.29 | ||||||

| 20 | … survey students’ interdisciplinary scientific inquiry of solving tasks of Gestaltungskompetenz. | 0.30 | |||||||

| Factor 5: Applying Methods of Evaluation (ESD/G) | |||||||||

| 21 | … appropriately select suitable methodical procedures by weighing the advantages and disadvantages of formative and summative evaluation procedures. | 0.60 | |||||||

| 22 | … apply methods for summative evaluation 13 (e.g., exam to review performance). 13 Evaluation of effects. | 0.58 | |||||||

| 23 | … analyze students’ abilities based on competence models (e.g., model for decision-making 14, sustainability triangle/quad 15). 14 A model that describes three requirements of ESD in the context of socioscientific decision-making: ‘Generating and Reflecting on Factual Information’, ‘Evaluation, Choice, and Reflection’, and ‘Understanding and Reflecting on Values and Norms’ (Bögeholz, 2013, p. 75). 15 Describes the three (social, economic, ecological) or four (plus cultural) dimensions of ESD, which should be considered for a solution to socioscientific issues (KMK & BMZ, 2016, p. 41). | 0.52 | 0.27 | ||||||

| 24 | … use methods for formative evaluation 16 (e.g., climate change concept map, questionnaire to survey everyday concepts on globalization). 16 Supporting the learning process. | 0.49 | |||||||

| 25 | … create tasks relating to the three requirement areas 17 using operators appropriate to the situation. 17 Requirement area I: “Reproduction”; Requirement area II: “Reorganization and Transfer”; Requirement area III: “Reflection, Evaluation, and Problem-Solving”. | 0.49 | |||||||

| Factor 6: Applying Media (G) | |||||||||

| 26 | … use the (interactive) whiteboard, beamer, and document camera as a medium to present (e.g., to visualize teaching materials and teaching subjects in students’ presentations). | −0.89 | |||||||

| 27 | … incorporate tablets, smartphones, and computers (e.g., apps to execute research 18, take up extracurricular expertises in the form of blogs, simulation games). 18 One example is the app “Get-neutral”, which can be used to scan different everyday products for their carbon footprint. In that way, students can research and assess whether they live sustainably (Rat für Nachhaltige Entwicklung, 2017). | −0.65 | |||||||

| 28 | … use the blackboard and the overhead projector to present charts (e.g., concept maps on climate change, flowchart on CO2 emissions). | −0.45 | |||||||

| Factor 7: Using ESD-specific Materials of the Research (ESD) | |||||||||

| 29 | … consider the guidelines of the Cross-Curricular Framework for Global Development Education when planning lessons. | 0.55 | |||||||

| 30 | … integrate materials of subject-specific programs (e. g., BLK 21 19, Transfer-21 20, Eine Welt in der Schule 21) when planning lessons. 19 The aim of the program of the Bund-Länder-Kommission (BLK) was to enshrine ESD in regular school practice as a follow-up to “Agenda 21” (BLK, 2005, p.7). 20 Follow-up program of the BLK 21 program. 21 Bremen-based lessons development project regarding the learning areas “Global Learning” and “Global Development”. | 0.54 | |||||||

| 31 | … take into account recent research findings when planning lessons (e. g., from journals such as the Journal of Geography, International Journal of Environmental and Science Education; from PISA studies). | 0.29 | |||||||

| Factor 8: Teaching Ethically Relevant Issues of ESD (ESD) | |||||||||

| 32 | … foster students’ handling of dilemmatic situations in the context of socioscientific decision-making competence 22, respectively political judgment competence and capacity for political action 23 cumulatively and systematically over the course of several school years. 22 Socioscientific decision-making is an area of competence to be fostered in science subjects. 23 Political judgment competence and capacity for political action are areas of competence in the social sciences. | 0.27 | −0.67 | ||||||

| 33 | … consider students’ difficulties with judging dilemmatic situations (e. g., not certified fishing and cultivation of cotton, roses, and coffee beans). | 0.27 | −0.43 | ||||||

| 34 | … foster students’ handling of dilemmatic situations in the context of socioscientific decision-making competence, respectively political judgment competence and capacity for political action cumulatively and systematically over the course of a single teaching unit. | 0.40 | −0.40 | ||||||

| 35 | … survey students’ ability to analyze and anticipate unsustainable developments and their global risks. | 0.30 | −0.37 | ||||||

| Factor Removed | Ratio | CFI | TLI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.49 | 0.916 | 0.906 | 0.045 [0.038–0.053] |

| 8 | 1.51 | 0.915 | 0.904 | 0.046 [0.039–0.054] |

| Self-Efficacy Factor | Subcategory of PCK (Transferred to ESD) | n | α1 | α2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fostering Gestaltungskompetenz and Generic Competence (ESD/G) (excluded after confirmatory factor analysis) | Curricular Demands | 4 | 0.84 | - |

| Including ESD-specific Instructional Strategies under Consideration of Students’ Motivation (ESD) | Subject/ESD-specific Strategies and Activities + Need | 7 | 0.85 | 0.77 |

| Using ESD-specific Educational Resources for School (ESD) | Curriculum Materials | 3 | 0.77 | 0.69 |

| Surveying Dimensions of Gestaltungskompetenz (ESD) | Dimensions of Gestaltungs- kompetenz to Assess | 6 | 0.79 | 0.74 |

| Applying Methods of Evaluation (ESD/G) | Methods of Assessing ESD Learning | 5 | 0.78 | 0.75 |

| Applying Media (G) | Representations | 3 | 0.73 | 0.64 |

| Using ESD-specific Materials of the Research (ESD) | Curriculum Materials | 3 | 0.68 | 0.65 |

| Teaching Ethically Relevant Issues of ESD (ESD) | New (=Learning Difficulties, Curricular Demands, Dimensions of Gestaltungskompetenz to Assess) | 4 | 0.79 | 0.59 |

| Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 | Factor 5 | Factor 6 | Factor 7 | Factor 8 | srCK | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 2 | 1 | |||||||

| Factor 3 | 0.30 ** | 1 | ||||||

| Factor 4 | 0.59 ** | 0.31 ** | 1 | |||||

| Factor 5 | 0.59 ** | 0.51 ** | 0.38 ** | 1 | ||||

| Factor 6 | 0.41 ** | 0.06 | 0.30 * | 0.24 | 1 | |||

| Factor 7 | 0.55 ** | 0.60 ** | 0.39 ** | 0.49 ** | 0.26 | 1 | ||

| Factor 8 | 0.70 ** | 0.39 ** | 0.70 ** | 0.67 ** | 0.31 * | 0.59 ** | 1 | |

| srCK | −0.26 ** | −0.23 ** | −0.28 ** | −0.24 ** | −0.13 | −0.25 ** | −0.36 ** | 1 |

| Phase of Teacher Education (Predictor) | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 | Factor 5 | Factor 6 | Factor 7 | Factor 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | −0.18 * | 0.09 | −0.18 * | 0.01 | −0.19 * | −0.21 ** | −0.03 |

| CI-95% | −0.32 to −0.04 | −0.07 to 0.24 | −0.32 to −0.04 | −0.14 to 0.16 | −0.36 to −0.01 | −0.35 to −0.06 | −0.19 to 0.13 |

| SE | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.08 |

| p-value | 0.014 | 0.268 | 0.010 | 0.891 | 0.038 | 0.006 | 0.696 |

| Participation in ESD Course (Predictor) | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 | Factor 5 | Factor 6 | Factor 7 | Factor 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | 0.21 ** | 0.19 * | 0.13 | 0.22 ** | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.13 |

| CI-95% | 0.07–0.35 | 0.04–0.35 | −0.01–0.27 | 0.08–0.36 | −0.04–0.33 | −0.13–0.19 | −0.04–0.30 |

| SE | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.09 |

| p-value | 0.003 | 0.015 | 0.077 | 0.002 | 0.119 | 0.710 | 0.134 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Handtke, K.; Richter-Beuschel, L.; Bögeholz, S. Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Teaching ESD: A Theory-Driven Instrument and the Effectiveness of ESD in German Teacher Education. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6477. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116477

Handtke K, Richter-Beuschel L, Bögeholz S. Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Teaching ESD: A Theory-Driven Instrument and the Effectiveness of ESD in German Teacher Education. Sustainability. 2022; 14(11):6477. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116477

Chicago/Turabian StyleHandtke, Kevin, Lisa Richter-Beuschel, and Susanne Bögeholz. 2022. "Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Teaching ESD: A Theory-Driven Instrument and the Effectiveness of ESD in German Teacher Education" Sustainability 14, no. 11: 6477. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116477

APA StyleHandtke, K., Richter-Beuschel, L., & Bögeholz, S. (2022). Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Teaching ESD: A Theory-Driven Instrument and the Effectiveness of ESD in German Teacher Education. Sustainability, 14(11), 6477. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116477