Abstract

Greenhouse gas emission is a major contributor to climate change and global warming. Many sustainability efforts are aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions. These include recycling and the use of renewable energy. In the case of recycling, the general population is typically required to at least temporarily store, and possibly haul, the materials rather than simply throwing them away. This effort from the general population is a key aspect of recycling, and in order for it to work, some investment of time and effort is required by the public. In the case of corrugated cardboard boxes, it has been observed that there is less motivation for the general population to recycle them. This paper explores different means of motivating people to reuse, and not just recycle, with different types of incentives. The paper addresses the use of persuasion techniques and operant conditioning techniques together to incent the general population to adopt sustainable efforts. The paper makes an attempt to segment the general population based on persuasion preference, operant condition preference, and personality type to use different forms of incentives and motivational work unlike any approaches found in the literature review. Four types of persuasion techniques and four types of operant conditioning are combined to give 16 different types of incentives. Two online surveys are conducted, and their data are analyzed (using entropy, Hamming distance, chi-square, and ANOVA). The results indicate that “positive reinforcement ethos” is a cost-effective way to incent the general population. The results of this study can be applied to a wide range of applications such as incentives for solar panels, incentives for vaccination, and other areas wherein sustainability-centric behavior is encouraged.

Keywords:

reuse; recycle; incentives; motivation; operant conditioning; persuasion; corrugated cardboard box 1. Introduction

Pollution is a major current global problem, as it leads to global warming and associated climate change due to the depletion of the ozone layer, increase in global temperature, rise in sea level, melting of glaciers, and other adverse events. According to the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), pollution is defined as “Any substances in water, soil, or air that degrade the natural quality of the environment, offend the senses of sight, taste, or smell, or cause a health hazard. The usefulness of the natural resource is usually impaired by the presence of pollutants and contaminants” [1].

To reduce global warming and climate change, humans can turn to the use of renewable fuels, use sustainable transportation, reduce waste, promote recycling, and other measures. One of the key aspects of all these solutions is to reduce the emission of greenhouse gases (GHGs). According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) fourth assessment report, “Recycling reduces GHG emissions through lower energy demand for production (avoided fossil fuel) and by substitution of recycled feedstocks for virgin materials” [2] (p. 602). In short, recycling leads to indirect energy-saving and an avoidance of/reduction in GHG emissions. The recycling process in the United States started as early as 1960 with the manufacturing of paper with recycled fibers from cotton and linen rags. Since then, the recycling industry has evolved and is applied worldwide for many different products and materials in addition to paper. The United States passed the Solid Waste Disposal Act in 1965 and the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act in 1976, both aimed at reducing waste and decreasing pollution. Although the recycling process is currently well established, the recycling rate in the United States in 2019 was only 32% [3]. EPA calculates recycling rates as the percentage of total municipal solid waste (MSW) recycled. The “recycling rate” metric can be confusing, as it accounts for the total waste received with respect to the percentage of waste that was recycled. Recent studies in the field of sustainability efforts have tried to identify the problems and barriers experienced in the recycling process in different fields and different parts of the world [4,5,6,7,8]. Another example of poor recycling efforts can be seen in the fact that 91.3% of all the plastic waste that is generated in the US was not recycled in the year 2018 [3]. Overall, limited improvement is observed in the US with respect to recycling rates [7].

A particular product of interest in the recycling/reuse arena is the “Corrugated Cardboard Box” (CCB). The CCB is widely used in the packaging industry and is made from wood. Approximately 100 billion boxes are manufactured in the US each year. Out of the 100 billion boxes, approximately 70–75% of these boxes are received for recycling each year [9,10]. The remaining 25–30% of the boxes are not received for recycling, and thus, cannot be recycled. In 2018, 96.5% of corrugated cardboard boxes that were actually received for recycling were recycled, whereas 2.82% of these boxes were mixed with landfills and 0.69% of these boxes were combusted [11]. In 2018, corrugated boxes were the largest single product category received as municipal solid waste in the US. Approximately 33.3 million tons of CCBs were received, out of which 0.94 million tons were mixed with landfills, 0.23 million tons were combusted, and 32.1 million tons were recycled.

Even if the above numbers are impressive, there are certain underlying problems with the recycling process of CCBs. According to the Corrugated Packaging Alliance [12] and the Fiber Box Association [13], a typical corrugated cardboard box is made up of 50% of recycled fiber. This also implies that, on average, every CCB contains 50% recycled fibers and 50% virgin fibers that are produced from trees. Thus, even if humankind manages to recycle all the CCBs ever produced, there will still be a need to cut down trees for virgin fibers to manufacture new CCBs. As [14] states “the process of manufacturing of raw materials also causes pollution”. Even though recycling helps in reducing the overall carbon emissions of a CCB over its lifecycle, it is not an absolute solution to the main problem. There is a need to further improve this process to reduce carbon emissions. Another problem with recycling CCBs is that the number of boxes received for recycling is low. Recycling a CCB can be achieved by taking the box to a recycling center or by placing the box in a recycling bin, if/where available. It has been observed that grocery stores and big-box stores recycled 90% to 100% of their CCBs. In an article by USA Today [15] Betsy Dorn, director of RSE USA, states that nationally, consumers send back 25% of their CCBs. The reason that the general population is not inclined to recycle the CCB varies. One of the major reasons is that consumers need to cut down the boxes in order to fit in the recycle bin and to be accepted by recycling service providers. The article further states that the general population is not particularly motivated to participate in that kind of extra work. According to the Recycling Partnership’s “State of Curbside Recycling” Report [16], only 60% of US homes have curbside recycling services. Thus, about 40% of US homes either do not have access to, or do not sign up for, curbside recycling. These are the main reasons for not receiving many of the CCBs for recycling with respect to the number manufactured each year.

In order to increase sustainable efforts, a new process needs to be established that tries to reuse the CCB multiple times before recycling it, and we also need to find a way to incent and motivate the general population towards accompanying sustainable efforts. The term “reuse” can be confusing as it is interpreted in different ways. The authors define “reusing the corrugated box” as using the corrugated box multiple times for packaging needs before discarding/recycling it. Although the “reuse” process has existed for decades, implementation of the reuse process of corrugated boxes by the general population using incentive strategies tied to personality was not found in the literature review. In this paper, the authors investigate different means to incent the general population towards sustainable efforts at a low cost. The hypothesis this paper evaluates is that segmenting the general population based on different personality types and motivational attributes, such as persuasion and operant condition types, will be beneficial for motivating them to reuse corrugated packaging.

2. Materials and Method

There are many ways to motivate an individual. Guay et al. [17] refer to motivation as the reason underlying behavior. Gredler [18] defines motivation as “the attribute that moves us to do or not do something”. As discussed before, there is a need to motivate the general population to reuse CCB. To motivate the general population, there needs to be a way to incent individuals, which is, in effect, the attribute/reason to be motivated. Incentives can be broadly categorized into two categories: financial incentives and non-financial incentives. In order to incent the general population, this paper divides the incentive procedure into two parts. The first part of an incentive procedure can be stated as the grabbing of attention of the target population (persuasion). The second part of the incentive procedure can be stated as modifying behavior to repeat the required task (operant conditioning).

Grabbing the attention of the target population is addressed through persuasion techniques. Perloff [19] states that persuasion involves communication that is focused on altering behavior and attitude. O’Keefe [20] states that persuasion is non-coercive and intentional communication that effectively changes the behavior with a change in mental state. There are four types of persuasion techniques that are used in this paper: ethos, pathos, logos, and aesthetics. These four types of persuasion techniques are defined below.

- Ethos—A persuasive technique that appeals via aspects of ethics, morals, conscience, values, standards, and principles.

- Pathos—A persuasive technique that appeals via emotions. These include aspects of memory, nostalgia, and shared experience.

- Logos—A persuasive technique that appeals via logic and reasoning. They usually include statistics, facts, and data.

- Aesthetics—A persuasive technique that appeals to beauty and people’s appreciation of things.

In order to potentially influence the behavior of the target population to repeat the required task, this paper explores the method of operant conditioning. B.F. Skinner [21] first introduced the concept of operant condition and defined it as “controlled by its consequences” [22]. There are four types of operant conditioning techniques that are used in this paper: positive reinforcement, negative reinforcement, positive punishment, and negative punishment. These four types of operant conditioning techniques are defined below.

- Positive Reinforcement—Positive reinforcement is adding a pleasant consequence that leads to repeating the behavior.

- Negative Reinforcement—Negative reinforcement is taking away unpleasant consequences, which leads to repeating the behavior.

- Positive Punishment—Positive punishment is adding an unpleasant consequence that leads to avoiding the repetition of the behavior.

- Negative Punishment—Negative punishment is taking away a pleasant consequence, which leads to avoiding the repetition of the behavior.

With both sets of four related incentives defined and explained, it is worth restating that in this paper, the incentives comprise two parts: operant conditioning and persuasion. Thus, Table 1 below gives the 16 types of incentive that are explored in this paper.

Table 1.

List of 16 types of incentives.

These 16 types of incentive are created by combining the four operant conditioning techniques and four persuasion techniques. It is argued that these 16 types of incentive should be tested for relative suitability for incenting sustainable efforts. In order to test these incentive methods, two surveys were conducted.

The authors also explored metrics that could influence or relate to the proposed 16 types of incentive. There are many examples of previous research where researchers have tried to pair the Myers–Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) with different behavioral traits [23,24,25,26]. MBTI is widely accepted in the industry and many other organizations [26]. MBTI is often used for hiring and managerial training in order to study the behavior of the candidate and account it for the required job responsibilities. MBTI consists of 16 types of personality. This paper investigates whether there is any influential relationship between the 16 types of personality with respect to the proposed 16 types of incentive. The 16 types of personality are based on 4 main factors with a continuum of personality scores or affinities, which are further simplified into two categories each: Energy (Introversion(I) or Extroversion(E)), Information (Intuition(N) or Sensing(S)), Decisions (Thinking(T) or Feeling(F)), and Organization (Judging(J) or Perceiving(P)). The combination of these 4 factors gives 16 different types of personalities. Data are collected by conducting surveys, and various analyses are performed to elicit the results from the data.

The methodology used in this paper is to test the hypothesis of segmenting the general population with respect to persuasion preference, operant condition preference, and personality type. This segmentation is hypothesized to be effective for motivating the general population to reuse the CCB.

2.1. Survey #1

There were 62 questions in total on this survey. The objective of this survey was to identify the operant conditioning and persuasion preference of each participant. This survey estimates each participants’ personality typing with 12 questions instead of the traditional 93 questions. This survey also tries to understand the participants’ perspectives on the 16 types of incentive that are proposed in this paper. Below are the types of questions that were included in this survey:

- Questions to assess personality type (12 questions)

- a.

- True or False questions (8 questions)

- b.

- Multiple-choice questions (4 questions)

- Questions to assess persuasion preference (25 questions)

- c.

- Likert-type questions (20 questions)

- d.

- Multiple-choice questions (5 questions)

- Questions to assess operant conditioning preference (25 Questions)

- e.

- Likert-type questions (20 questions)

- f.

- Multiple-choice questions (5 questions)

Survey #1 identified and assigned the operant conditioning preference, persuasion preference, and personality type of the participant. Survey #1 includes Likert scale questions to examine the need and possibility to customize the incentive methods for a specific population group. These different types of questions help to evaluate whether there is a need to customize the incentive type with respect to individual preference (customized incentivization) over a single method of incentivization (universal incentivization). The main output from this survey was to understand the preference of the target population regarding the 16 types of incentive. It was also important to find how much each incentive method would cost, and to estimate the cost required to move a participant from their preferred incentive type to a new one.

Therefore, to address these new questions regarding the financial aspect of the incentives, the authors conducted a second survey (survey #2).

2.2. Survey #2

There were 25 questions in total in this survey. The objective of this survey was to analyze the financial aspects of each of the 16 incentives. The questions were also worded to identify how much it would cost to move someone from their preferred operant conditioning type to a new one by using their preferred persuasion type. This survey also tried to understand participants’ perspectives on these incentives by asking them qualitative questions. Below are the types of questions that were included in this survey.

- One multiple-choice question to assess how much it would take for participants to be motivated in their own preferred type of incentive.

- Twelve multiple-choice questions to assess how much of an incentive would be required for them to choose from one operant conditioning type over another associated with their preferred persuasion type (12 questions for 12 transitions between four operant conditioning types).

- Twelve qualitative questions about their views on every single transition between the four operant conditioning types.

Survey #2 identifies how much would it cost to motivate a particular individual to make a preferred effort at reuse. Additionally, it identifies and quantifies how much would it cost to change their operant conditioning and still motivate them to carry out sustainable efforts.

3. Results

3.1. Survey #1 Results

Survey #1 was published online on the “LinkedIn” social media platform, as well as being sent to the email lists of the students, faculty, and staff of Colorado State University. The Qualtrics tool was used to create the survey and collect the responses online. Survey #1 was active for 26 days and received 156 responses. The metadata from Qualtrics show that survey #1 received responses from participants in four countries. The median time to complete Survey #1 was 18.15 min.

Operant conditioning preferences and persuasion preferences were elicited based on the participant’s response to multiple-choice questions that compared the four options to each other, respectively.

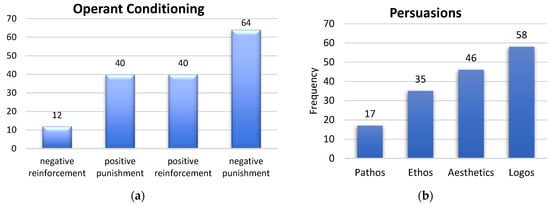

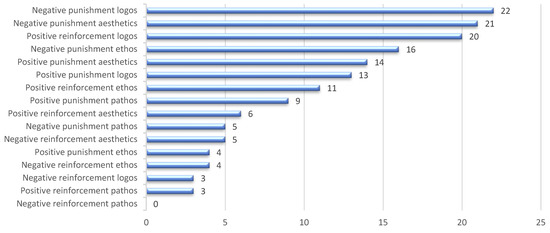

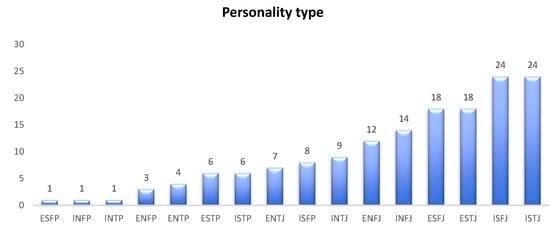

The personality types of the participants were based on 12 questions, out of which 4 questions were taken from an article published on the internet [27], and the remaining 8 questions were created by authors in true/false format. For each of the four categories of personality type, the “best of three” rule was used to classify participants’ preferences. Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3 show the data that were collected from survey #1 for 156 participants.

Figure 1.

Survey results for (a) number of participants belonging to each of the four operant conditioning preferences; (b) number of participants belonging to each of the four persuasion preferences.

Figure 2.

Survey results for number of participants belonging to each of the 16 types of incentive.

Figure 3.

Survey results for the number of participants belonging to each of the 16 personality types.

3.2. Analysis of Survey #1

There were five types of analysis performed on the survey #1 data, as detailed in number (Section 3.2.1) through (Section 3.2.5) in the paragraphs that follow.

3.2.1. Comparing Multiple-Choice Questions to Likert Scale Questions

The primary goal behind this survey was to identify participants’ preferences for operant conditioning, persuasion, and personality type. As stated previously, it is also important to identify whether there is a need for customization with respect to the individual participant or group of participants. In order to identify if there is a need for customization, this paper compares the Likert scale question to multiple-choice questions with respect to their output on participants’ operant condition preferences and persuasion preferences. The hypothesis used here is that when the results of operant conditioning and persuasion are compared for both multiple-choice questions and Likert scale questions, if the percentage of results from both question sets is more than the expected values (25% on random guessing), then the customization approach may be valuable and shall be considered. On the other hand, if the percentage of results from both question sets is less than or equal to the “randomly” expected value (25%), then the customization approach is deemed less valuable.

Five Likert scale questions were included in survey #1 for each of the four types of operant conditioning and persuasion types. Weighting from 1 to 5 was assigned to five options of the Likert scale question (strongly disagree, somewhat disagree, neither agree nor disagree, somewhat agree, strongly agree) and participants’ preferences were based on the highest scores in their respective categories for the operant conditioning and persuasion question set. Out of 156 responses, 33 responses were indeterminate (same score for two or more categories of operant conditioning or persuasion); therefore, they were excluded from this particular analysis only. Table 2 below gives the results for 123 (of 156 possible) responses, which shows that the accuracy between these question sets is less than the expected value.

Table 2.

Comparison of results from multiple-choice questions to those of Likert scale questions.

3.2.2. Self-Assessments of Questions

This paper also examines the questions that were asked in survey #1. This analysis is important enough that each question is assessed to check if it is confusing. In order to assess the questions, entropy calculations were performed. Entropy, in simple terms, is a measure of randomness. Entropy calculation is based on the number of responses received by each option that is provided by the question. Entropy is high or maximum for a particular question when the total responses are equally divided between the available options. On the other hand, the entropy of a particular question is low, or near minimum, when the total responses are focused on only one option from the available options. Equation 1 below gives the formula to calculate the entropy [28]:

Here, I is the particular bin, is the percentage of the events in bin (i), and N is the number of bins.

Likert Scale Question

Survey #1 includes a total of 40 Likert scale questions, wherein each question is intended to evaluate participant preference type. Each Likert scale question consists of five options, as elaborated in the previous analysis. This question type tests participants’ views on the question based on agreement or disagreement. Therefore, the expected results for the population of response are to be concentrated around two options (strongly agree or strongly disagree). The higher the entropy of the Likert scale response, the less general agreement there is on a particular question. High entropy in the Likert scale response can also be computed for questions that are less clear. Table 3 below gives the question numbers, ranked with respect to their entropy value for each category.

Table 3.

Calculated entropy results and ranking of questions based on entropy from Likert scale questions evaluating (a) persuasion preference and (b) operant conditioning preference.

Multiple-Choice Questions

Survey #1 includes 8 multiple-choice questions, four for operant conditioning preferences and four for persuasion preferences. The entropy method is again used to evaluate the multiple-choice questions for confusion. However, in this case, a single question compares four categories. Therefore, the expected results for the population of responses are to be distributed over the four available options. The higher the entropy of multiple-choice responses, the less general agreement there is on a particular question. Low entropy in multiple-choice responses can also be computed for questions that are less clear. Table 4 provides the question numbers, ranked with respect to their entropy value for each category.

Table 4.

Calculated entropy results and ranking of questions based on entropy from multiple-choice questions.

3.2.3. Chi-Square Test

Survey #1 had 12 questions that assessed the personality type of the participant. These questions were asked to identify whether there is any influential relationship between the 16 types of personality and 16 types of incentive. In order to test this hypothesis, a Chi-square test was conducted. The Chi-square test is used to statistically evaluate the goodness of fit between the expected values and measured values.

The data were analyzed for four types of personality traits (Energy, Information, Decisions, and Organization) with respect to the four types of persuasion and four types of operant conditions. The results are provided in Table 5.

Table 5.

Chi-square score and p-value results for personality traits with respect to persuasion and operant conditioning.

Thus, the results demonstrate that Energy and Information traits may have an influential relationship with operant conditioning preference.

3.2.4. ANOVA Test

Larson [29] states that “Analysis of variance (ANOVA) is a statistical technique to analyze variation in a response variable (continuous random variable) measured under conditions defined by discrete factors (classification variables, often with nominal levels).” In other words, this paper uses the ANOVA test to investigate whether there is any influential relationship between the different types of categories with respect to persuasion preferences or operant conditioning preferences. Table 6 and Table 7 provide a list of dependent variables and independent variables which were analyzed with each other (80 tests in total).

Table 6.

List of independent variables and dependent variables used in ANOVA test.

Table 7.

Significant results (p-value < 0.05) of ANOVA tests with significance value between dependent variable and independent variables.

The main purpose of this test was to identify whether there is any statistically meaningful relationship between different categories with respect to persuasion or operant conditioning preference. The results in Table 7 give all the possible influential relationships that are possible and are significant.

3.2.5. Hamming Distance for Personality Test

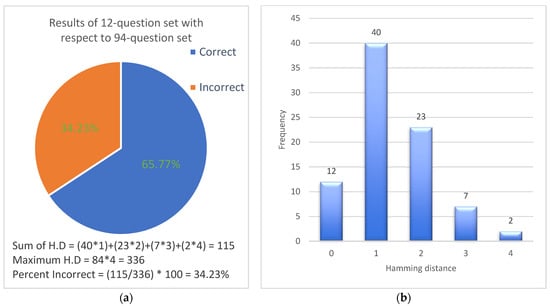

Hamming [30] proposed this method to estimate the error in telecommunication by counting the number of flipped bits in a binary word. The sum of unmatched bits is the Hamming distance. Saad et al. [31] states that the “Hamming distance is known for its ability in calculating the difference between two sets/elements”. Smaller Hamming distances correspond to a closer similarity between two elements. The Hamming distance is used to evaluate and compare the personality type questions. Two types of question sets are compared here. In the first type, participants were asked 12 questions in order to assign a personality type. In the second type, participants were provided with a single qualitative question with an external link to the official website of 16 personalities [32] where participants answered 93 questions to find their personality type and entered their results as an answer to this question. Thus, this paper compares the results of the 12-question set with the 96-questions set. The Hamming distance is calculated by comparing two words in a letter-to-letter format to find out the discrepancies between them. Table 8 provides an example comparing two results from both question sets.

Table 8.

Example for Hamming distance calculation.

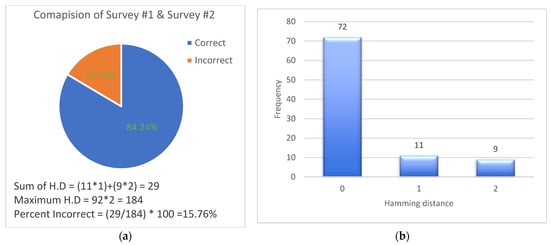

The Hamming distance for the above example is 2 because of discrepancies in the first and last categories (Energy and Organization). Figure 4 shows the results for 84 participants who reported their personality type from the 93-question set. As seen in Figure 4a,b, when the 12-question set was compared to an extensive 93-question set, the 12-question set resulted in 65.8% agreement when compared using the Hamming distance. Out of 84 cases, there were 40 cases wherein the difference between the personality type was just a single letter (a trait in terms of personality category).

Figure 4.

(a) Results for percentage correct and incorrect when 12-question set is compared to the 93-question set; (b) results for Hamming distance for personality test comparing 12-question set to 93-question set.

3.3. Survey #2 Results and Analysis

Survey #2 was sent to the participants of survey #1 (156 individuals) as a follow-up survey. Out of 156 participants, 96 participants responded to survey #2 (it was active for 54 days). Thus, survey #2 had a response rate of 61.5%. Qualtrics was used again to create the survey and to collect the responses online. The median time to complete survey #2 was 8.25 min. After completion of survey #2, the participants received an email about their personality type, persuasion preferences, and operant conditioning preferences, which were determined by their responses to survey #1 and survey #2.

The survey #2 results and analysis can be divided into four parts, as given below in the sections labeled (Section 3.3.1, Section 3.3.2, Section 3.3.3 and Section 3.3.4)

3.3.1. Quantitative Analysis—Persuasion Approach

Survey #2 included multiple-choice questions that asked about how much would be required, in terms of a monetary incentive, for a participant to select a different operant condition rather than their identified preferred operant condition. There were 12 questions for 6 transitions in both directions, as explained below:

- Positive reinforcement <-> Negative reinforcement

- Positive reinforcement <-> Positive punishment

- Positive reinforcement <-> Negative punishment

- Negative reinforcement <-> Positive punishment

- Negative reinforcement <-> Negative punishment

- Positive punishment <-> Negative punishment

Table 9 gives results for these 12 questions, which are categorized with respect to the persuasion type used to move one’s preference of operant condition.

Table 9.

Results of cost in $ for the transition from one operant condition to another operant condition by using different types of persuasion.

3.3.2. Quantitative Analysis—Operant Conditioning Approach

In the survey #2 questionnaire, one question was asked to every participant to identify how much money they would require to be motivated for sustainable efforts in their own preferred incentive type, which was determined in survey #1. The question was based on the participant’s preferred operant conditioning type. Table 10 provides the result for this question, which is given by calculating the mean monetary incentive for each category of operant conditioning.

Table 10.

Results of amount of monetary incentive required per box for participants to stay in their preferred operant condition.

3.3.3. Comparing Survey #1 to Survey #2

The analysis of survey #1 provided the persuasion preferences and operant condition preferences of the participants. From Survey #2, the participants’ responses were examined to determine the operant-conditioning-based question for which they selected the least amount of money to reuse the corrugated boxes. Based on their response, an operant conditioning preference was inferred. Thus, participants’ operant conditioning preferences based on survey #1 and survey #2 were compared and a Hamming distance was used for their analysis. Below are the results of the Hamming distance.

As shown in Figure 5, 84.2% of the time, the operant conditioning results (positive vs. negative, reinforcement vs. punishment) were in agreement after comparing operant conditioning preferences from both surveys for each participant. Additionally, it can be seen from the bar graph that out of 92 cases, there were 72 cases (78.3%) wherein the difference between the operant conditioning preferences in terms of Hamming distance is zero.

Figure 5.

(a) Results for percentage correct and incorrect on comparing operant conditioning preferences from both surveys; (b) results for Hamming distance on comparing both surveys for operant conditioning preferences.

3.3.4. Qualitative Analysis

As the qualitative questions were optional, out of the 96 responses to survey #2, only 32 participants answered the qualitative questions. Qualitative questions allow for the collection and study of the reasoning behind the answers to the quantitative questions, as well as of the whole study. Below is the summary of the responses to these questions

- The most-mentioned comment by participants was that they do not need any special incentive and would reuse the cardboard boxes voluntarily.

- Participants selected $3 because it is a good balance between $1 and $5.

- Participants felt like threatening (positive punishment and/or negative punishment) is not a good method of providing incentive and they did not like it.

- Participants had questions and comments on practicality, such as the space that the box would require in their home and the effort of finding someone who would be in need of the boxes and then donating it to them.

- Participants thought that when there is a risk of being threatened, reminding them to reuse is important.

- The point of the survey was confusing to a small set of participants.

- Participants thought that there is a risk in reusing a box as they speculated that it would break during transit.

4. Discussion

There were 40 Likert scale questions asked in survey #1, to cover the possibility of any type of customization that may be required for incentivization. The results of Table 2 indicate that when both the multiple-choice questions and the Likert scale questions are compared, their percentage accuracy (eliciting the same results) is less than that of the randomly expected value (25%). Using entropy, the questions asked in survey #1 were evaluated. It was important to assess the questions to find out if they included leading/confusing questions that might affect the results. Assessing the questions based on entropy helps to set a baseline for future researchers or for a researcher who is trying to replicate this research. Table 3 compares Likert scale questions to each other with respect to entropy. It can be stated that Q11, Q16, Q20, and Q23 are the least confusing questions in the logos, ethos, pathos, and aesthetics categories, respectively, or that they have the greatest overall agreement among survey respondents. Questions Q28, Q36, Q41, and Q42, by the same measure, are the least confusing questions for the positive reinforcement, negative reinforcement, positive punishment, and negative punishment categories, respectively. Table 4 compares multiple-choice questions based on entropy, and it can be stated that Q49 for persuasion and Q52 for operant conditioning are the least confusing questions, respectively, or that they have the least agreement among respondents.

The paper also evaluated whether there is an influential relationship between the 16 types of personality and the 16 types of incentive. The results for the chi-square test from Table 5 indicate that the 16 types of personality have no strong influential relationship with the 16 types of incentive. In order to see if there is any influential relationship between different types of variables, an ANOVA test was carried out. Table 7 gives the significant results that were found by comparing ten independent variables with 8 dependent variables. These results indicate that there are differently influenced subpopulations. Survey #1 also introduced a 12-question set to elicit the personality type of the participant. This 12-question set was then compared to the more traditional 93-question set. The accuracy of the 12-question set was found to be 65.8% using the Hamming distance. Thus, the main result of survey #1 was to develop a generic method of incentivization for the general population. Building on that result, survey #2 was conducted to elicit how much it would cost to incent the general population to adopt sustainable efforts. Survey #2 evaluated the cost factor of the incentives and an incentivization method that was cost-effective as well as being motivational to the general population for sustainable efforts. From Table 9, it can be argued that the “ethos” persuasion technique was the most cost-effective method to motivate participants to change their preferred operant conditions, while still motivating them to adopt sustainable efforts. Similarly, from Table 10, in terms of operant conditioning, “positive reinforcement” appeared to be the most cost-effective method for sustainable efforts. In order to motivate the general population towards sustainable efforts, “positive reinforced ethos” was, based on the results presented here, an effective yet cost-efficient method of incentivizing the general population. One of the pieces of feedback from the qualitative questions was about not liking the positive punishment and negative punishment types of incentive. This further supports the recommendations of the study, which is to use ethos and positive reinforcement to influence people to reuse CCBs.

There were no similar studies found in the literature review, where incentives were used for the “reuse” process over the recycling process for the general population. Past and current research have tried to incent the general population to make a sustainable effort such as recycling waste [4,5,8,33]. The authors of papers [34,35,36] talk about indirect incentives to the general population based on waste management service charges. The authors of [34,35,36] test the effects of indirect financial incentives by using pay-by-weight or pay as you throw (PAYT) which means to pay a customized trash service fee instead of a fixed service that depends on the weight of the trash. All three reference papers conclude that incentives do make a positive difference in the current situation. Reference [37] talks about the use of financial incentives in terms of virtual currency to motivate the general population to increase plastic recycling. Thus, research that yields a unique method and cost to motivate the general population was not found.

One of the issues/challenges for the proposed method is how the general population would accept that the packaging they are using/received has been reused multiple times. Another challenge is installing a new system to collect and store the used corrugated boxes: this will be a challenge as they would need to be handled gently compared to other waste of recycling goods and would require more storage space as boxes would need to be in their proper forms to be reused again. Lastly, the feasibility of using a corrugated box multiple times to carry packages would need to be explored and researched. Although it has been observed that corrugated boxes can be used 20–30 times to transport products in an industrial setting [38,39], research on the reuse of corrugated boxes outside of industrial use can be explored in the future.

5. Conclusions

The purpose of this research was to find a way to motivate the general population to adopt more sustainable efforts. This paper addressed finding a low-cost solution to incent the general population. Considering the results and analyses, it can be concluded that segmenting the general population based on different personality types and motivational attributes such as persuasion and operant condition types would not add significant value in motivating them to reuse the corrugated packaging. Survey #2 also tested the consistency of participants’ preferences, as survey #2 had small changes in the questions to evaluate very tight sensitivity for different ways of incentivizing while comparing two incentives. It was expected that the participants would change their preference or confuse their preference from survey #1; however, this was not observed. In fact, participants were consistent with their views from survey #1 while answering survey #2.

It can be observed that incenting the general population with a generic method appears to be more effective than trying to craft a customized method for a specific set of people grouped by the persuasion, operant conditioning, and personality types explored. Thus, the recommendation from this research would be to use “positive reinforcement + ethos” as an incentive to motivate the general population to reuse the corrugated boxes instead of recycling them. The recommendation and output from this paper may impact the mindset of the general population to reuse their own corrugated boxes and those of others, rather than placing the corrugated boxes into the normal flow of the trash or recycling.

The future scope and prospects of this study include how to put across the message of the incentive, to evaluate how to better incent the general population. Framing the incentive message to be more efficient and effective is important. Furthermore, this study could act as a basis for future studies. There is a strong possibility of the use of these paired sets of incentive approaches for sustainable cars, solar panels, vaccinations, etc. The authors have also made sure to evaluate their questions from the survey, so that future researchers can replicate or use the questionnaire (included in Appendix A and Appendix B), accordingly, for future studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.K. and S.S.; methodology, H.K. and S.S.; formal analysis, H.K. and S.S.; writing—original draft preparation, H.K.; writing—review and editing, S.S.; visualization, H.K.; supervision, S.S.; funding acquisition, S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Colorado State University SoGES (School of Global Environmental Sustainability), Global Challenges Research Team 4 Grant and the APC was funded by Colorado State University’s Systems Engineering Department.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Colorado State University (protocol code: 1932, date of approval: 25 June 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The (anonymized) data is available upon request and approval by the Colorado State University Institutional Review Board (CSU IRB).

Acknowledgments

We wish to show our appreciation to Angie Chromiak for guiding us through the IRB application. We would also like to thank the following people for helping us with the distribution of surveys and administrative tasks: Ingrid Bridge, Chrissy Charny, Katharyn Peterman, and Mary Gomez.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Survey questionnaires for Survey #1:

- Q1. Select one from the following options that you feel describes you the best of the four choices.

- While walking in the park, when I see a plastic bag on a footpath, I pick up the bag and throw it in the recycling bin to reduce pollution.

- I participate in a survey only if the organizer will give me some kind of cash reward.

- I would participate in a charity fundraiser program to help the needy.

- I prefer things based on their appearance over their performance.

- Q2.Select one of the following that suits you best.

- If my company would give a reward to the employees who work on weekends, I would definitely work on some/all the weekends to get that reward.

- I prefer working late hours sometimes just to prevent the long lectures from my boss about not completing the task.

- Even if the street is empty, I would prefer to walk the extra distance to cross the street at a crosswalk rather than jaywalking. The penalty for jaywalking in Colorado can be up to $100.

- After hearing that I can be a potential candidate for a promotion, I am working more than usual because I fear I might lose the promotion opportunity if I don’t work hard.

- Q3.You are totally exhausted because of a busy week which was difficult and disappointing. How do you plan to spend your weekend? (Question modified from one originally presented on the Brightside website).

- I would call my friends to check on their plans for the weekend. I would then plan with everyone to go to one of the following: the newly-opened restaurant/the new highly-rated comedy in the cinemas/the paintball club.

- I will turn my phone to “silent mode” and stay at home. I would watch the new episode of my favorite TV series, do a puzzle, and take a long bath with a novel.

- Q4. Which of the following descriptions suits you more? (Question modified from one originally presented on the Brightside website).

- I pay attention to details and assess real situations, because the most important thing for me is about what’s happening now and here.

- Facts are not so exciting! I love to play and dream over upcoming events in my mind as I rely more on intuition than on information.

- Q5.A competitor of your current employer is trying to entice you. You have some doubts because the salary is much higher there when compared to the current employer. But the staff at your current employer is great. Moreover, the head of your department hinted that he will recommend you to be the boss when he retires. How are you going to make a decision? (Question modified from one originally presented on the Brightside website).

- I will find all the available information about the competitor and ask my HR manager for advice. I would then draw a chart with all the merits and demerits of both the companies. In such cases, it is important to weigh up all the advantages and disadvantages and assess the situation with a calm mind.

- I usually follow my heart! So, I will just listen to my feelings and make a decision.

- Q6.Your close friends’ wedding is just two weeks away. How are your preparations going? (Question modified from one originally presented on the Brightside website).

- Three weeks ago, I brought a new suit for the wedding/chose the keyboard player who will play a medley of our school songs/collected the couple’s photo love story/wrote a poem/made an appointment with the stylist. I prefer to be fully prepared.

- Why prepare? I will be enjoying myself at the party and having fun. I will improvise my wedding toast. The best things happen spontaneously.

Likert Scale questionnaire:

Five Options to each question below—(Strongly agree, Somewhat agree, Neither agree nor disagree, Somewhat disagree and Strongly disagree.)

- Q7.I take additional effort to complete a task if I receive a cash reward after completing it.

- Q8. I sometimes ignore going the extra mile even if I know I will be rewarded with cash.

- Q9. I would walk for a mile to get to my destination rather than book a cab to save money.

- Q10.I will devote a couple of hours per month to watch a short lecture per month if I receive a cash reward.

- Q11. I don’t participate in a survey if they don’t give me some kind of reward (cash, coupon, etc), as I think it is a waste of my time.

- Q12. I do things that are ethically correct even if I don’t necessarily want to do them.

- Q13. I would prefer driving an electric car over gasoline cars, even if the electric cars are costlier, because I believe it will reduce pollution.

- Q14. I prefer plastic bags over fabric bags in grocery stores because fabric bags are expensive and plastic bags are free.

- Q15. I would help my friend on an exam even if it is against my ethics because a friend in need is a friend indeed.

- Q16. I would participate in an activity that is against my ethics if I get a suitable reward for it.

- Q17. I sometimes feel bad for the less fortunate, so I donate food/money to them while coming from grocery shopping.

- Q18. I would make a donation for cleaning random lakes or beaches in the world, because I fear that aquatic life will be affected by man-made pollution.

- Q19. I would bring a souvenir from a fun place as a memory.

- Q20. I try to reduce carbon emissions from my side because I fear global warming will affect human beings in the future.

- Q21. I would choose the decision made by my mind over the heart.

- Q22. I would choose a stylish car that has a great color/artwork on it over a boring-looking car with high mileage.

- Q23. I prefer a restaurant with good food quality over a restaurant with a pleasant ambience.

- Q24. I wear clothes that look good on me even if they are not that comfortable.

- Q25. I like to decorate my room with the cool things that I like.

- Q26. I would buy option “b” over “a”. Even if “b” is expensive. (Refer Figure A1).

Figure A1. Reference figure comparing two glasses.

Figure A1. Reference figure comparing two glasses. - Q27.I tend to complete my work on time, before deadline, to impress my boss and receive praise.

- Q28. If I know I could receive a reward for completing some tasks, I give my 100% to complete that task.

- Q29. I would think of buying an electric car because the federal government gives tax credits to those who buy an electric vehicle.

- Q30. I tend to make an extra effort in my work only when I know I will be rewarded for doing it.

- Q31. I would usually travel an extra mile for a coffee if I know I will be rewarded by the best coffee in the town!

- Q32. I like to clean my work desk every day so that I avoid losing important documents/things.

- Q33. I try to complete assignments before deadline to avoid penalties.

- Q34. I always charge my phone/carry a power bank before leaving home to avoid having a discharged phone.

- Q35. While cooking I tend to use less salt than the recipe calls for, as I can always add salt later.

- Q36. I tend to charge my laptop before a meeting to avoid running out of power during the meeting.

- Q37. I avoid working overtime, even if my work is past deadline, since I could be penalized for going into overtime.

- Q38. I avoid jaywalking even on a side street to avoid a fine.

- Q39. I try to pay my credit card bill on time because if I don’t, they would penalize me.

- Q40.I try to pay my rent on time because if I don’t, my landlord penalizes me.

- Q41. I always avoid parking my car in no parking area because if I do, the authorities can tow my vehicle.

- Q42. I pay the Wi-Fi bill on time because if don’t then I could lose Wi-Fi as well as my TV privileges that come with it.

- Q43. I work hard at my job because I know my boss can demote me if I don’t.

- Q44. I keep on subscribing to Amazon prime so that I can get prime delivery as well as prime video privileges.

- Q45. I always maintain the minimum balance on my debit card to avoid losing my cash reward.

- Q46. I avoid being late to work because I don’t like to miss the best parking slot.

Multiple-choice questions below:

- Q47.Select one of the following options which appeal to you the most for recycling cardboard boxes.

- Congratulations! Recycling this box will give you “5” dollars. Recycling 2 boxes/month could give you “120” dollars/year!

- Congratulations! You are contributing to saving the planet earth!

- Thank you! Your recycling of this box is contributing to healing the ozone layer!

- Good job! By recycling this box you are keeping our environment clean.

- Q48.Select one of the following options which appeal to you the most for recycling cardboard boxes.

- Recycling this box will save 20% of the shipping charges on your mail.

- Recycling “20” boxes will save “5” liters of oil which would contribute to preventing Global Warming.

- Thank you! Your recycling of this box is contributing to saving Florida panthers.

- Good job! By recycling this box you are preventing it from adding it to the landfill.

- Q49.Select one of the following options which appeal to you the most for recycling cardboard boxes.

- Failing to recycle this box will get you off the priority delivery option for your mail/package delivery: only people who recycle 5 boxes/month get to be on the priority delivery list.

- Failing to recycle this box will increase pollution by 3 kgCO2eq. amount of carbon emission.

- Failing to recycle this box will increase global warming.

- Failing to recycle this box will increase the dirty landfills.

- Q50. Select one of the following options which appeal to you the most for recycling cardboard boxes.

- Failing to recycle this box will prevent you from getting a discount on the shipping cost.

- Failing to recycle this box will increase the depletion of fossil fuels.

- Failing to recycle this box will decrease the chances of saving polar bears.

- Failing to recycle this box will make our environment dirty.

- Q51. Select one of the following options which appeal to you the most for recycling cardboard boxes.

- Congratulations! Recycling this box will give you “5” dollars. Recycling 2 boxes/month could give you “120” dollars/year!

- Recycling this box will save 20% of the shipping charges on your mail.

- Failing to recycle this box will get you off the priority delivery option for your mail/package delivery: only people who recycle 5 boxes/month get to be on the priority delivery list.

- Failing to recycle this box will prevent you from getting a discount on the shipping cost.

- Q52.Select one of the following options which appeal to you the most for recycling cardboard boxes.

- Congratulations! You are contributing to saving the planet!

- Recycling “20” boxes will save “5” liters of oil which would contribute to preventing Global Warming.

- Failing to recycle this box will increase pollution by 3 kgCO2eq. amount of carbon emission.

- Failing to recycle this box will increase the depletion of fossil fuels.

- Q53.Select one of the following options which appeal to you the most for recycling cardboard boxes.

- Thank you! Your recycling of this box is contributing to healing the ozone layer!

- Thank you! Your recycling of this box is contributing to saving Florida panthers.

- Failing to recycle this box will increase Global warming.

- Failing to recycle this box will decrease the chances of saving polar bears.

- Q54.Select one of the following options which appeal to you the most for recycling cardboard boxes.

- Good job! By recycling this box, you are keeping our environment clean.

- Good job! By recycling this box, you are preventing it from being added to the landfill.

- Failing to recycle this box will increase the size of the landfill.

- Failing to recycle this box will make our environment dirty.

- Q55.Please provide your personality type if you can. (If you don’t know, you can use this website [32] (optional).Text entry - ___________________________________________________

True or False questions below:

- Q56.It is easy for me to make new friends.

- Q57. I like to initiate talking even if it is with a stranger.

- Q58. I tend to think more about the future than the present.

- Q59. I tend to think more conceptually than practically.

- Q60. For me, fair judgment is more important than compassion.

- Q61. For me, appreciation is more important than the medals I receive.

- Q62. I prefer my vacations to be spontaneous rather than planned.

- Q63. I don’t like routines.

Appendix B

Survey questionnaires for Survey #2:

The first question is different in survey #2. This question was dependent on the participants’ operant conditioning preferences and persuasion preferences. The four options for this question were $1/reused cardboard box, $3/reused cardboard box, $5/reused cardboard box, and another amount which is more than $5/reused box (please specify). So, there are fifteen unique first questions as follows:

Positive Reinforcement Aesthetic:

We want to incentivize you by donating to the charitable organization of your choice that prevents the addition of trash in the landfills for each cardboard box you reuse. What is the minimum amount of money that should be donated for you to reuse the boxes instead of disposing of them?

Positive Reinforcement Logos:

We want to incentivize you by giving a cash reward for each cardboard box you reuse. What is the minimum amount of money that should be rewarded for you to reuse the boxes instead of disposing of them?

Positive Reinforcement Ethos:

We want to incentivize you by donating to the charitable organization of your choice that is trying to reduce pollution to save the planet for every cardboard box you reuse. What is the minimum amount of money that should be donated for you to reuse the boxes instead of disposing of them?

Positive Reinforcement Pathos:

We want to incentivize you by donating to the charitable organization of your choice that is making an effort to heal the ozone layer for each cardboard box you reuse. What is the minimum amount of money that should be donated for you to reuse the boxes instead of disposing them?

Negative Reinforcement Aesthetics:

We want to incentivize you by donating to the charitable organization of your choice that cleans the trash in your city for each cardboard box you reuse. What is the minimum amount of money that should be donated for you to reuse the boxes instead of disposing of them?

Negative Reinforcement Logos:

We want to incentivize you by saving money off your shipping charges on your mail for every cardboard box you reuse. What is the minimum amount of money that should be saved in the shipping charges for you to reuse the boxes instead of disposing of them?

Negative Reinforcement Ethos:

We want to incentivize you by donating to the charitable organization of your choice that is making an effort to prevent global warming for each cardboard box you reuse. What is the minimum amount of money that should be donated for you to reuse the boxes instead of disposing of them?

Negative Reinforcement Pathos—No participant in this category

Positive Punishment Aesthetics:

We want to incentivize you by threatening to eliminate the donation to the charitable organization that is making an effort to decrease the dirty landfills for every cardboard box you fail to reuse. What is the minimum amount of money that, if eliminated from the donation, would incent you to reuse the boxes instead of disposing of them?

Positive Punishment Logos:

We want to incentivize you by threatening to increase the shipping charges on your mail for every cardboard box you fail to reuse. What is the minimum amount of money that, if increased in the shipping cost would incent you to reuse the boxes instead of disposing of them?

Positive Punishment Ethos:

We want to incentivize you by the threat of eliminating the donation to the charitable organization of your choice that is making an effort to decrease pollution for every cardboard box you fail to reuse. Thus, failing to reuse the cardboard box would increase pollution. What is the minimum amount of money that, if eliminated from the donation, would incent you to reuse the boxes instead of disposing of them?

Positive Punishment Pathos:

We want to incentivize you by threatening to eliminate the donation to the charitable organization of your choice that is making an effort to decrease global warming for each cardboard box you fail to reuse. Eliminating this donation increases global warming. What is the minimum amount of money if eliminated from the donation would incent you to reuse the boxes instead of disposing them?

Negative Punishment Aesthetics:

We want to incentivize you by the threat of eliminating the donation of your share to the charitable organization that is making an effort to keep our environment clean for every cardboard box you fail to reuse. What is the minimum amount of money that, if eliminated from the donation, would incent you to reuse the boxes instead of disposing of them?

Negative Punishment Logos:

We want to incentivize you by threatening to eliminate the cash reward for every cardboard box you fail to reuse. What is the minimum amount of money that, if eliminated from the cash reward, would incent you to reuse the boxes instead of disposing of them?

Negative Punishment Ethos:

We want to incentivize you by the threat of eliminating the donation to the charitable organization of your choice that is making an effort to decrease the depletion of fossil fuel for every cardboard box you fail to reuse. What is the minimum amount of money that, if eliminated from the donation, would incent you to reuse the boxes instead of disposing of them?

Negative Punishment Pathos:

We want to incentivize you by threatening to eliminate the donation to the charitable organization of your choice that is making an effort to save polar bears for each cardboard box you fail to reuse. What is the minimum amount of money if eliminated from the donation would incent you to reuse the boxes instead of disposing of them?

The remaining 12 multiple-choice questions were dependent upon the participants’ persuasion preferences. The four options to this question were $1/reused cardboard box, $3/reused cardboard box, $5/reused cardboard box, and another amount which is more than $5/reused box (please specify). So, below are the four sets of 12 questions that were asked in survey #2 depending upon the participants’ persuasion preferences:

Persuasion preferences—Aesthetics:

- Q2.(Current plan)—Currently you are being incentivized by donating to the charitable organization of your choice that prevents the addition of trash to the landfill for each cardboard box you reuse.(New plan)—We want to incentivize you by donating to the charitable organization of your choice that cleans the trash in your city for each cardboard box you reuse.We want to move you from your current incentivization plan to the new one. What is the minimum amount of money that should be donated in the new plan for you to reuse the boxes instead of disposing of them?

- Q3.(Current plan)—Currently you are being incentivized by donating to the charitable organization of your choice that cleans the trash in your city for each cardboard box you reuse.(New plan)—We want to incentivize you by donating to the charitable organization of your choice that prevents the addition of trash in the landfills for each cardboard box you reuse.We want to move you from your current incentivization plan to the new one. What is the minimum amount of money that should be donated in the new plan for you to reuse the boxes instead of disposing of them?

- Q4.(Current plan)—Currently you are being incentivized by donating to the charitable organization of your choice that cleans the trash in your city for each cardboard box you reuse.(New plan)—We want to incentivize you by the threat of eliminating the donation of your share to the charitable organization that is making an effort to keep our environment clean for every cardboard box you fail to reuse.We want to move you from your current incentivization plan to the new one. What is the minimum amount of money that, if eliminated from the new plan, would incent you to reuse the boxes instead of disposing of them?

- Q5. (Current plan)—Currently you are being incentivized by the threat of eliminating the donation to the charitable organization that is making an effort to keep our environment clean for every cardboard box you fail to reuse.(New plan)—We want to incentivize you by donating to the charitable organization of your choice that is trying to keep our environment clean for every cardboard box you reuse.We want to move you from your current incentivization plan to the new one. What is the minimum amount of money that should be donated in the new plan for you to reuse the boxes instead of disposing of them?

- Q6. (Current plan)—Currently you are being incentivized by donating to the charitable organization of your choice that is keeping our environment clean for each cardboard box you reuse.(New plan)—We want to incentivize you by threatening to eliminate the donation to the charitable organization that is making an effort to decrease the dirty landfills for every cardboard box you fail to reuse.We want to move you from your current incentivization plan to the new one. What is the minimum amount of money that, if eliminated from the new plan, would incent you to reuse the boxes instead of disposing of them?

- Q7. (Current plan)—Currently you are being incentivized by the threat of eliminating the donation to the charitable organization that is making an effort to decrease the dirty landfills for every cardboard box you fail to reuse. Eliminating this donation increases the dirty landfills in your city.(New plan)—We want to incentivize you by donating to the charitable organization of your choice that is making an effort to keep our environment clean for each cardboard box you reuse.We want to move you from your current incentivization plan to the new one. What is the minimum amount of money that should be donated in the new plan for you to reuse the boxes instead of disposing of them?

- Q8. (Current plan)—Currently you are being incentivized by donating to the charitable organization of your choice that prevents the addition of waste in landfills for each cardboard box you reuse.(New plan)—We want to incentivize you by threatening to eliminate the donation to the charitable organization that is making an effort to decrease the dirty landfill for each cardboard box you reuse.We want to move you from your current incentivization plan to the new one. What is the minimum amount of money that, if eliminated from the new plan, would incent you to reuse the boxes instead of disposing of them?

- Q9. (Current plan)—Currently you are being incentivized by the threat of eliminating the donation to the charitable organization that cleans the trash in your city for each cardboard box that you fail to reuse. Eliminating this donation increases the dirty landfills in your city.(New plan)—We want to incentivize you by donating to the charitable organization of your choice that prevents the addition of waste in the landfills for each cardboard box you reuse.We want to move you from your current incentivization plan to the new one. What is the minimum amount of money that should be donated in the new plan for you to reuse the boxes instead of disposing of them?

- Q10. (Current plan)—Currently you are being incentivized by donating to the charitable organization of your choice that prevents the addition of waste in the landfills for each cardboard box you reuse.(New plan)—We want to incentivize you by the threat of eliminating the donation to the charitable organization that is making an effort to keep our environment clean for each cardboard box you reuse.We want to move you from your current incentivization plan to the new one. What is the minimum amount of money that, if eliminated from the new plan, would incent you to reuse the boxes instead of disposing of them?

- Q11. (Current plan)—Currently you are being incentivized by the threat of eliminating the donation to the charitable organization that is making an effort to keep our environment clean for each cardboard box you reuse. Eliminating this donation would make our city dirty.(New plan)—We want to incentivize you by donating to the charitable organization of your choice that is making an effort to prevent the addition of waste to the landfills for every cardboard box you reuse.We want to move you from your current incentivization plan to the new one. What is the minimum amount of money that should be donated in the new plan for you to reuse the boxes instead of disposing of them?

- Q12.(Current plan)—Currently you are being incentivized by the threat of eliminating the donation to the charitable organization that cleans the trash in your city for each cardboard box you reuse. Eliminating this donation would increase the trash in the city.(New plan)—We want to incentivize you by the threat of eliminating the donation to the charitable organization that works to clean up trash in the city and landfill for each cardboard box you reuse. Eliminating this donation will take away the chances of cleaning our city.We want to move you from your current incentivization plan to the new one. What is the minimum amount of money that, if eliminated from the new plan, would incent you to reuse the boxes instead of disposing of them?

- Q13. (Current plan)—Currently you are being incentivized by the threat of eliminating the donation to the charitable organization that works to clean up trash in the city and landfill for each cardboard box you reuse. Eliminating this donation would take away the chances of cleaning our city.(New plan)—We want to incentivize you by the threat of eliminating the donation to the charitable organization that cleans the trash in your city for each cardboard box you reuse. Eliminating this donation will increase the trash in the city.We want to move you from your current incentivization plan to the new one. What is the minimum amount of money that, if eliminated from the new plan, would incent you to reuse the boxes instead of disposing of them?

Persuasion preferences—Logos:

- Q2. (Current plan)—Currently you are being incentivized by getting a cash reward for each cardboard box you reuse.(New plan)—We want to incentivize you by saving money off your shipping charges on your mail for every cardboard box you reuse.We want to move you from your current incentivization plan to the new one. What is the minimum amount of money that should be saved in the new plan for you to reuse the boxes instead of disposing of them?

- Q3. (Current plan)—Currently you are being incentivized by saving money off your shipping charges on your mail for every cardboard box you reuse.(New plan)—We want to incentivize you by giving you a cash reward for each cardboard box you reuse.We want to move you from your current incentivization plan to the new one. What is the minimum amount of money that should be rewarded in the new plan for you to reuse the boxes instead of disposing of them?

- Q4. (Current plan)—Currently you are being incentivized by getting a cash reward for each cardboard box you reuse.(New plan)—We want to incentivize you by threatening to eliminate the cash reward for every cardboard box you fail to reuse.We want to move you from your current incentivization plan to the new one. What is the minimum amount of money that, if eliminated from the new plan, would incent you to reuse the boxes instead of disposing of them?

- Q5. (Current plan)—Currently you are being incentivized by the threat of eliminating the cash reward for every cardboard box you fail to reuse.(New plan)—We want to incentivize you by giving a cash reward for each cardboard box you reuse.We want to move you from your current incentivization plan to the new one. What is the minimum amount of money that should be rewarded in the new plan for you to reuse the boxes instead of disposing of them?

- Q6. (Current plan)—Currently you are being incentivized by getting a cash reward for each cardboard box you reuse.(New plan)—We want to incentivize you by threatening to increase the shipping charges on your mail for every cardboard box you fail to reuse.We want to move you from your current incentivization plan to the new one. What is the minimum amount of money that, if increased in the shipping cost in the new plan, would incent you to reuse the boxes instead of disposing of them?

- Q7. (Current plan)—Currently you are being incentivized by the threat of increasing the shipping charges on your mail for every cardboard box you fail to reuse.(New plan)—We want to incentivize you by giving a cash reward for each cardboard box you reuse.We want to move you from your current incentivization plan to the new one. What is the minimum amount of money that should be rewarded in the new plan for you to reuse the boxes instead of disposing of them?

- Q8. (Current plan)—Currently you are being incentivized by saving money off your shipping charges on your mail for every cardboard box you reuse.(New plan)—We want to incentivize you by threatening to increase the shipping charges on your mail for every cardboard box you fail to reuse.We want to move you from your current incentivization plan to the new one. What is the minimum amount of money that, if increased in the shipping cost in the new plan, would incent you to reuse the boxes instead of disposing of them?

- Q9. (Current plan)—Currently you are being incentivized by threatening to increase the shipping charges on your mail for every cardboard box you fail to reuse.(New plan)—We want to incentivize you by saving money off your shipping charges on your mail for every cardboard box you reuse.We want to move you from your current incentivization plan to the new one. What is the minimum amount of money that should be saved in the new plan for you to reuse the boxes instead of disposing of them?

- Q10. (Current plan)—Currently you are being incentivized by saving money off your shipping charges on your mail for every cardboard box you reuse.(New plan)—We want to incentivize you by threatening to eliminate the cash reward for every cardboard box you fail to reuse.We want to move you from your current incentivization plan to the new one. What is the minimum amount of money that, if eliminated from the new plan, would incent you to reuse the boxes instead of disposing of them?

- Q11. (Current plan)—Currently you are being incentivized by threatening to eliminate the cash reward for every cardboard box you fail to reuse.(New plan)—We want to incentivize you by saving money off your shipping charges on your mail for every cardboard box you reuse.We want to move you from your current incentivization plan to the new one. What is the minimum amount of money that should be saved in the new plan for you to reuse the boxes instead of disposing of them?

- Q12. (Current plan)—Currently you are being incentivized by the threat of increasing the shipping charges on your mail for every cardboard box you fail to reuse.(New plan)—We want to incentivize you by the threat of eliminating the cash reward for every cardboard box you fail to reuse.We want to move you from your current incentivization plan to the new one. What is the minimum amount of money if eliminated from the new plan would incent you to reuse the boxes instead of disposing of them?

- Q13.(Current plan)—Currently you are being incentivized by the threat of eliminating the cash reward for every cardboard box you fail to reuse.(New plan)—We want to incentivize you by threatening to increase the shipping charges on your mail for every cardboard box you fail to reuse.We want to move you from your current incentivization plan to the new one. What is the minimum amount of money if increased in the shipping cost in the new plan would incent you to reuse the boxes instead of disposing of them?

Persuasion preferences—Ethos:

- Q2. (Current plan)—Currently you are being incentivized by donating to the charitable organization of your choice that is trying to reduce pollution to save the planet for every cardboard box you reuse.(New plan)—We want to incentivize you by donating to the charitable organization of your choice that is making an effort to prevent global warming for each cardboard box you reuse.We want to move you from your current incentivization plan to the new one. What is the minimum amount of money that should be donated in the new plan for you to reuse the boxes instead of disposing of them?

- Q3. (Current plan)—Currently you are being incentivized by donating to the charitable organization of your choice that is making an effort to prevent global warming for each cardboard box you reuse.(New plan)—We want to incentivize you by donating to the charitable organization of your choice that is trying to reduce pollution to save the planet for every cardboard box you reuse.We want to move you from your current incentivization plan to the new one. What is the minimum amount of money that should be donated in the new plan for you to reuse the boxes instead of disposing of them?

- Q4. (Current plan)—Currently you are being incentivized by donating to the charitable organization of your choice that is trying to reduce pollution to save the planet for every cardboard box you reuse.(New plan)—We want to incentivize you by the threat of eliminating the donation to the charitable organization of your choice that is making an effort to decrease the depletion of fossil fuel for every cardboard box you fail to reuse.We want to move you from your current incentivization plan to the new one. What is the minimum amount of money that, if eliminated from the new plan, would incent you to reuse the boxes instead of disposing of them?

- Q5. (Current plan)—Currently you are being incentivized by the threat of eliminating the donation to the charitable organization of your choice that is making an effort to decrease the depletion of fossil fuel for every cardboard box you fail to reuse.(New plan)—We want to incentivize you by donating to the charitable organization of your choice that is trying to reduce pollution to save the planet for every cardboard box you reuse.We want to move you from your current incentivization plan to the new one. What is the minimum amount of money that should be donated in the new plan for you to reuse the boxes instead of disposing of them?

- Q6. (Current plan)—Currently you are being incentivized by donating to the charitable organization of your choice that is trying to reduce pollution to save the planet for every cardboard box you reuse.(New plan)—We want to incentivize you by the threat of eliminating the donation to the charitable organization of your choice that is making an effort to decrease pollution for every cardboard box you fail to reuse. Thus, failing to reuse the cardboard box would increase pollution.We want to move you from your current incentivization plan to the new one. What is the minimum amount of money that, if eliminated from the new plan, would incent you to reuse the boxes instead of disposing of them?