Relationship between Entrepreneurial Orientation and Business Performance among Malay-Owned SMEs in Malaysia: A PLS Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Dimensions of Entrepreneurial Orientation

“… points to a number of actions that can be regarded as entrepreneurial, i.e., the development of new products and markets, proactive behavior, risk-taking, the start-up of new organizations and the growth of an existing organization”.

2.2. Relationships between Entrepreneurial Orientation and Business Performance

3. Research Framework and Hypotheses

3.1. Autonomy

3.2. Risk-Taking and Its Relationship with Business Performance

3.3. Proactiveness

3.4. Innovativeness

3.5. Achievements

4. Research Design

4.1. Survey Design and Sampling

4.2. Measurement

| Autonomy |

| The firm administrator gives a unique idea and made a success out of it. |

| The firm enables the passing of entrepreneurial ideas generated by members of firms to manage. |

| The firm administrators don’t take ideas generated by members of firms and make their own decisions. |

| The firm administrators are driven by the vision to establish their realm. |

| The firm autonomy orientation gives a positive result to the firm performance |

| Proactiveness |

| The firm takes responsibility and does whatever it takes to ensure an entrepreneurial venture produces a successful outcome. |

| The firm’s pro-activeness involves insistence, flexibility, and readiness to assume responsibility for failure. |

| This firm enables us to anticipate future needs and take opportunities. |

| This firm capitalizes on opportunities to gain benefit. |

| This proactive orientation made influenced the firm performance. |

| Risk-Taking |

| The firm involves in errors a certain degree of risk and speculation. |

| Firms always avoid taking a risk when the risk is unavoidable. |

| The risk taken by the firms is predictable. |

| The risk taken is calculated in the failure of the firms. |

| The risk-taking orientation of the firm influence the performance of the company. |

| Innovativeness |

| This firm’s environment follows the shape of the latest market. |

| This firm comes out with new ideas for the product, services, administration, or technological processes. |

| The new idea applied to this firm is relevant to the firm, market, and environment. |

| The new idea from the firm can be cultured to all the staff and administration |

| Innovativeness of the company gives positive results to the firm performance. |

4.3. Data Analysis Technique

4.3.1. Measuring Construct Validity and Discriminant Validity

4.3.2. Reliability

4.3.3. Structural Model

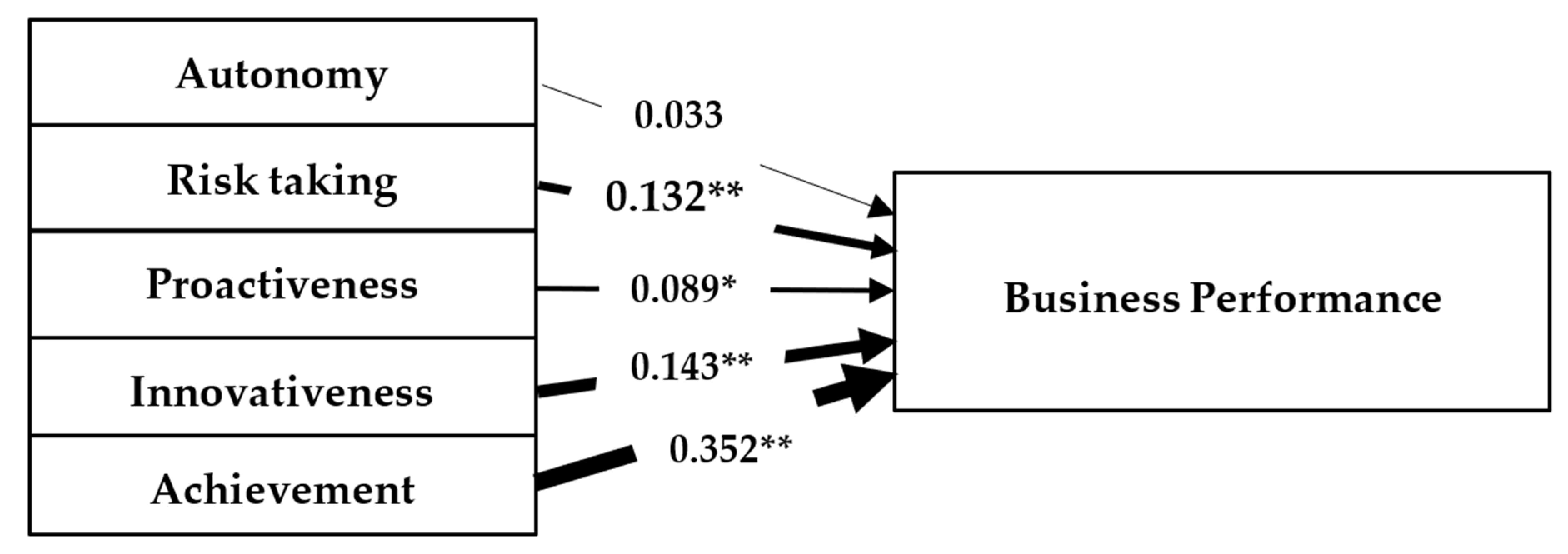

5. Hypotheses Discussion

6. Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

7. Implications

7.1. Implications for Research

7.2. Implications for Practice

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Iqbal, S.; Moleiro Martins, J.; Nuno Mata, M.; Naz, S.; Akhtar, S.; Abreu, A. Linking Entrepreneurial Orientation with Innovation Performance in SMEs; the Role of Organizational Commitment and Transformational Leadership Using Smart PLS-SEM. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, G.T.; Dess, G.G. Clarifying the Entrepreneurial Orientation Construct and Linking It to Performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1996, 21, 135–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgelman, R.A. A Process Model of Internal Corporate Venturing in the Diversified Major Firm. Adm. Sci. Q. 1983, 28, 223–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runyan, R.C.; Ge, B.; Dong, B.; Swinney, J.L. Entrepreneurial Orientation in Cross–Cultural Research: Assessing Measurement Invariance in the Construct. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2012, 36, 819–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.-M.; Sun, W.-Q.; Tsai, S.-B.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, Q. An Empirical Study on Entrepreneurial Orientation, Absorptive Capacity, and SMEs’ Innovation Performance: A Sustainable Perspective. Sustainability 2018, 10, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Keh, H.T.; Nguyen, T.T.M.; Ng, H.P. The Effects of Entrepreneurial Orientation and Marketing Information on the Performance of SMEs. J. Bus. Ventur. 2007, 22, 592–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapienza, H.J.; De Clercq, D.; Sandberg, W.R. Antecedents of International and Domestic Learning Effort. J. Bus. Ventur. 2005, 20, 437–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbreath, J.; Lucianetti, L.; Thomas, B.; Tisch, D. Entrepreneurial Orientation and Firm Performance in Italian Firms: The Moderating Role of Competitive Strategy. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2020, 26, 629–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, J.; Ortt, R. Entrepreneurial Orientation and Firm Performance: The Mediating Role of Functional Performances. Manag. Res. Rev. 2018, 41, 878–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martens, C.D.P.; Lacerda, F.M.; Belfort, A.C.; de Freitas, H.M.R. Research on Entrepreneurial Orientation: Current Status and Future Agenda. IJEBR 2016, 22, 556–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, C.; De Clercq, D.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, C. Government Institutional Support, Entrepreneurial Orientation, Strategic Renewal, and Firm Performance in Transitional China. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2019, 25, 433–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, S.H. The Dynamics between Entrepreneurial Orientation, Transformational Leadership, and Intrapreneurial Intention in Iranian R&D Sector. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2017, 23, 769–792. [Google Scholar]

- Semrau, T.; Sigmund, S. Networking Ability and the Financial Performance of New Ventures: A Mediation Analysis among Younger and More Mature Firms. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2012, 6, 335–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutscher, F.; Zapkau, F.B.; Schwens, C.; Baum, M.; Kabst, R. Strategic Orientations and Performance: A Configurational Perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 849–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abebe, M. Electronic Commerce Adoption, Entrepreneurial Orientation and Small-and Medium-Sized Enterprise (SME) Performance. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2014, 21, 100–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakala, H. Strategic Orientations in Management Literature: Three Approaches to Understanding the Interaction between Market, Technology, Entrepreneurial and Learning Orientations. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2011, 13, 199–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Star Strengthening SMEs—Backbone of the Economy 2021. Available online: https://www.thestar.com.my/business/business-news/2021/12/13/strengthening-smes---backbone-of-the-economy (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Charlesworth, H. Increasing the Supply of Bumiputra Entrepreneur; Research Report; MARAs Institute of Technology: Shah Alam, Malaysian, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Al Mamun, A.; Fazal, S.A. Effect of Entrepreneurial Orientation on Competency and Micro-Enterprise Performance. Asia Pacific J. Innov. Entrep. 2018, 12, 379–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Loong Lee, W.; Chong, A.L. The Effects of Entrepreneurial Orientation on the Performance of the Malaysian Manufacturing Sector. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2019, 11, 30–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okhomina, D. Entrepreneurial Orientation and Psychological Traits: The Moderating Influence of Supportive Environment. J. Behav. Stud. Bus. 2010, 2, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Rauch, A.; Frese, M. Let’s Put the Person Back into Entrepreneurship Research: A Meta-Analysis on the Relationship between Business Owners’ Personality Traits, Business Creation, and Success. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2007, 16, 353–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiklund, J. Entrepreneurial Orientation as Predictor of Performance and Entrepreneurial Beh Aviour in Small Firms: Longitudinal Evidence. Front. Entrep. Res. 1998, 18, 283–296. [Google Scholar]

- Herani, R.; Andersen, O. Does Environmental Uncertainty Affect Entrepreneurs’ Orientation and Performance? Empirical Evidence from Indonesian SMEs. Gadjah Mada Int. J. Bus. 2012, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, G.T.; Dess, G.G. Linking Two Dimensions of Entrepreneurial Orientation to Firm Performance: The Moderating Role of Environment and Industry Life Cycle. J. Bus. Ventur. 2001, 16, 429–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, G.T.; Erdogan, B. If Not Entrepreneurship, Can Psychological Characteristics Predict Entrepreneurial Orientation? A Pilot Study. ICFAI J. Entrep. Dev. 2004, 1, 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver, K.D.; Dickson, P.H.; Marino, L.; Davis, L.; During, W.; Hoy, F. Where Are the Entrepreneurs? A Ten Country Comparison of the Dimensions of the Entrepreneurial Orientations or Owner/Managers in Small and Medium Enterprises. In Proceedings of the 46th International Council for Small Business, Taipei, Taiwan, 17–20 June 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Awang, A.; Ahmad, Z.A.; Asghar, A.R.S.; Subari, K.A. Entrepreneurial Orientation among Bumiputera Small and Medium Agro-Based Enterprises (BSMAEs) in West Malaysia: Policy Implication in Malaysia. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2010, 5, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Asmit, B.; Koesrindartoto, D.P. Identifying the Entrepreneurship Characteristics of the Oil Palm Community Plantation Farmers in the Riau Area. Gadjah Mada Int. J. Bus. 2015, 17, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covin, J.G.; Slevin, D.P. Strategic Management of Small Firms in Hostile and Benign Environments. Strateg. Manag. J. 1989, 10, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, G.A. Cross-Cultural Reliability and Validity of a Scale to Measure Firm Entrepreneurial Orientation. J. Bus. Ventur. 1997, 12, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dess, G.G.; Lumpkin, G.T.; Covin, J.G. Entrepreneurial Strategy Making and Firm Performance: Tests of Contingency and Configurational Models. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 677–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, P.H.; Weaver, K.M. Environmental Determinants and Individual-Level Moderators of Alliance Use. Acad. Manag. J. 1997, 40, 404–425. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatraman, N. Strategic Orientation of Business Enterprises: The Construct, Dimensionality, and Measurement. Manag. Sci. 1989, 35, 942–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kotler, P.; Armstrong, G. Principles of Marketing (16th Global Edition) 2013; S4Carlisle: Chennai, India, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Schumpeter, J.A. Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy; Routledge: London, UK, 2010; ISBN 0203857097. [Google Scholar]

- D’aveni, R.A.; Ravenscraft, D.J. Economies of Integration versus Bureaucracy Costs: Does Vertical Integration Improve Performance? Acad. Manag. J. 1994, 37, 1167–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D. The Correlates of Entrepreneurship in Three Types of Firms. Manage. Sci. 1983, 29, 770–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreiser, P.; Marino, L.; Weaver, K.M. Assessing the psychometric properties of the entrepreneurial orientation scale: A multi-country analysis. Entre. Theo. Prac. 2002, 26, 71–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, B.; Kraimer, M.L.; Liden, R.C. Work Value Congruence and Intrinsic Career Success: The Compensatory Roles of Leader-member Exchange and Perceived Organizational Support. Pers. Psychol. 2004, 57, 305–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, G.T. Do New Entrant Firms Have an Entrepreneurial Orientation. In Proceedings of the Academy of Management Annual Meeting, San Diego, CA, USA, 10–12 August 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Krauss, S.I.; Frese, M.; Friedrich, C.; Unger, J.M. Entrepreneurial Orientation: A Psychological Model of Success among Southern African Small Business Owners. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2005, 14, 315–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A. Technology Strategy and Financial Performance: Examining the Moderating Role of the Firm’s Competitive Environment. J. Bus. Ventur. 1996, 11, 189–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covin, J.G.; Slevin, D.P. A Conceptual Model of Entrepreneurship as Firm Behavior. Entrep. theory Pract. 1991, 16, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauch, A.; Wiklund, J.; Lumpkin, G.T.; Frese, M. Entrepreneurial Orientation and Business Performance: Cumulative Empirical Evidence. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 761–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulthard, M. The Role of Entrepreneurial Orientation on Firm Performance and the Potential Influence of Relational Dynamism. J. Glob. Bus. Technol. 2007, 3, 29. [Google Scholar]

- Madsen, E.L. The Significance of Sustained Entrepreneurial Orientation on Performance of Firms–A Longitudinal Analysis. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2007, 19, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, I.H. The Relationship between Entrepreneurial Orientation and Firm Performance in China. SAM Adv. Manag. J. 2006, 71, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Jantunen, A.; Puumalainen, K.; Saarenketo, S.; Kyläheiko, K. Entrepreneurial Orientation, Dynamic Capabilities and International Performance. J. Int. Entrep. 2005, 3, 223–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-H.; Huang, J.-W.; Tsai, M.-T. Entrepreneurial Orientation and Firm Performance: The Role of Knowledge Creation Process. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2009, 38, 440–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.L. Firm-Level Entrepreneurship and Performance: An Examination and Extension of Relationships and Measurements of the Entrepreneurial Orientation Construct; The University of Texas at Arlington: Arlington, TX, USA, 2007; ISBN 0549145044. [Google Scholar]

- Baba, R.; Elumalai, S. Entrepreneurial Orientation of SMEs in Labuan and Its Effects on Performance. Fac. Econ. Bus. 2011, 117, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Bavon, A. Public Enterprise Reform in Ghana: A Study of the Effects of Institutional Change on Organizational Performance 1994. Ph.D. Thesis, The Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L.C. Control, Incentives and Competition: The Impact of Reform on Chinese State-owned Enterprises. Econ. Transit. 2000, 8, 151–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubo, I.; Saka, A. An Inquiry into the Motivations of Knowledge Workers in the Japanese Financial Industry. J. Knowl. Manag. 2002, 6, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eriksson, J.; Thunberg, N. Resources and Entrepreneurial Orientation: Empirical Findings from the Software Industry of Sri Lanka. Master’s Thesis, Jönköping University, Jönköping, Sweden, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kusumawardhani, A. The Role of Entrepreneurial Orientation in Firm Performance: A Study of Indonesian SMEs in the Furniture Industry in Central Java. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Wollongong, Kowloon City, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gitman, L.J.; Juchau, R.; Flanagan, J. Principles of Managerial Finance; Pearson Higher Education AU: London, UK, 2015; ISBN 144253642X. [Google Scholar]

- Palich, L.E.; Bagby, D.R. Using Cognitive Theory to Explain Entrepreneurial Risk-Taking: Challenging Conventional Wisdom. J. Bus. Ventur. 1995, 10, 425–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmore, A.; Carson, D.; O’Donnell, A. Small Business Owner-managers and Their Attitude to Risk. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2004, 22, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couppey, M.; Roux, Y. Investigating the Relationship between Entrepreneurial and Market Orientations within French SMEs and Linking It to Performance 2007. Master’s Thesis, Umeå School of Business and Economics, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, M.; Morgan, R.E. Deconstructing the Relationship between Entrepreneurial Orientation and Business Performance at the Embryonic Stage of Firm Growth. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2007, 36, 651–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kuratko, D.F. Corporate Entrepreneurship. In Routledge Companion to Makers of Modern Entrepreneurship; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2016; p. 154. [Google Scholar]

- Naldi, L.; Nordqvist, M.; Sjöberg, K.; Wiklund, J. Entrepreneurial Orientation, Risk Taking, and Performance in Family Firms. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2007, 20, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebora, T.C.; Lee, S.M.; Sukasame, N. Critical Success Factors for E-Commerce Entrepreneurship: An Empirical Study of Thailand. Small Bus. Econ. 2009, 32, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kropp, F.; Lindsay, N.J.; Shoham, A. Entrepreneurial Orientation and International Entrepreneurial Business Venture Startup. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2008, 14, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landstrom, H. Pioneers in Entrepreneurship and Small Business Research; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; Volume 8, ISBN 0387236333. [Google Scholar]

- Ireland, R.D.; Hitt, M.A.; Sirmon, D.G. A Model of Strategic Entrepreneurship: The Construct and Its Dimensions. J. Manag. 2003, 29, 963–989. [Google Scholar]

- Hult, G.T.M.; Hurley, R.F.; Knight, G.A. Innovativeness: Its Antecedents and Impact on Business Performance. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2004, 33, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S.-J. Entrepreneurial Orientation, Environmental Scanning Intensity, and Firm Performance in Technology-Based SMEs. Front. Entrep. Res. 2001, 35, 356–367. [Google Scholar]

- Avlonitis, G.J.; Salavou, H.E. Entrepreneurial Orientation of SMEs, Product Innovativeness, and Performance. J. Bus. Res. 2007, 60, 566–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitriah, I. Innovation Intensity: Its Antecedents and Effects on Business Performance of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in the Malaysian Manufacturing Sector 2007; University of Wollongong: Kowloon City, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- McClelland, D.C. The Achieving Society; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1961; pp. 210–215. [Google Scholar]

- Koop, S.; De Reu, T.; Frese, M. Entrepreneurial Orientation and Personal Initiative. In Success and Failure of Microbusiness Owners in Africa: A Psychological Approach; Greenwood Publishing Group: Westport, CT, USA, 2000; p. 55. [Google Scholar]

- Rauch, A.; Frese, M. Psychological Approaches to Entrepreneurial Success: A General Model and an Overview of Findings. Int. Rev. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2000, 15, 101–142. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, L.M.; Spencer, P.S.M. Competence at Work Models for Superior Performance; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; ISBN 812651633X. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, N.R.; Bracker, J.S. Role of Entrepreneurial Task Motivation in the Growth of Technologically Innovative Firms: Interpretations from Follow-up Data. J. Appl. Psychol. 1994, 79, 627–630. [Google Scholar]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.-G. Statistical Power Analyses Using G* Power 3.1: Tests for Correlation and Regression Analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cohen, J. A Power Primer. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinartz, W.; Haenlein, M.; Henseler, J. An Empirical Comparison of the Efficacy of Covariance-Based and Variance-Based SEM. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2009, 26, 332–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kohli, A.K.; Shervani, T.A.; Challagalla, G.N. Learning and Performance Orientation of Salespeople: The Role of Supervisors. J. Mark. Res. 1998, 35, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chien, C.-C.; Hung, S.-T. Goal Orientation, Service Behavior and Service Performance. Asia Pacific Manag. Rev. 2008, 13, 513–529. [Google Scholar]

- Song, M.; Droge, C.; Hanvanich, S.; Calantone, R. Marketing and Technology Resource Complementarity: An Analysis of Their Interaction Effect in Two Environmental Contexts. Strateg. Manag. J. 2005, 26, 259–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawes, J. The Relationship between Subjective and Objective Company Performance Measures in Market Orientation Research: Further Empirical Evidence. Mark. Bull. Mark. Massey Univ. 1999, 10, 65–75. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, J.A.; Robbins, D.K.; Robinson Jr, R.B. The Impact of Grand Strategy and Planning Formality on Financial Performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 1987, 8, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dess, G.G.; Robinson, R.B., Jr. Measuring Organizational Performance in the Absence of Objective Measures: The Case of the Privately-held Firm and Conglomerate Business Unit. Strateg. Manag. J. 1984, 5, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schalk, A.P. Effects of Market Orientation on Business Performance: Empirical Evidence from Iceland. Univ. Icel. 2008, 6, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Mooi, E.A. Response-Based Segmentation Using Finite Mixture Partial Least Squares. In Proceedings of the Data Mining; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 19–49. [Google Scholar]

- Compeau, D.; Higgins, C.A.; Huff, S. Social Cognitive Theory and Individual Reactions to Computing Technology: A Longitudinal Study. MIS Q. 1999, 23, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aibinu, A.A.; Al-Lawati, A.M. Using PLS-SEM Technique to Model Construction Organizations’ Willingness to Participate in e-Bidding. Autom. Constr. 2010, 19, 714–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aibinu, A.A.; Ling, F.Y.Y.; Ofori, G. Structural Equation Modelling of Organizational Justice and Cooperative Behaviour in the Construction Project Claims Process: Contractors’ Perspectives. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2011, 29, 463–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.J.; Raposo, M.L.; Rodrigues, R.G.; Dinis, A.; do Paço, A. A Model of Entrepreneurial Intention: An Application of the Psychological and Behavioral Approaches. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2012, 19, 424–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triguero-Sánchez, R.; Peña-Vinces, J.C.; Sánchez-Apellániz, M. Hierarchical Distance as a Moderator of HRM Practices on Organizational Performance. Int. J. Manpow. 2013, 34, 794–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barclay, M.J.; Smith, C.W.; Watts, R.L. The Determinants of Corporate Leverage and Dividend Policies. J. Appl. Corp. Financ. 1995, 7, 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Z.; Waszink, A.B.; Wijngaard, J. An Instrument for Measuring TQM Implementation for Chinese Manufacturing Companies. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2000, 17, 730–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, S.; D’Ambra, J.; Ray, P. Trustworthiness in MHealth Information Services: An Assessment of a Hierarchical Model with Mediating and Moderating Effects Using Partial Least Squares (PLS). J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2011, 62, 100–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nunnally, J.C. An Overview of Psychological Measurement. In Clinical Diagnosis of Mental Disorders; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, P.S.P.; Cheung, S.O. Structural Equation Model of Trust and Partnering Success. J. Manag. Eng. 2005, 21, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Will, S. SmartPLS 2.0 (M3); Beta: Hamburg, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wetzels, M.; Odekerken-Schröder, G.; Van Oppen, C. Using PLS Path Modeling for Assessing Hierarchical Construct Models: Guidelines and Empirical Illustration. MIS Q. 2009, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.; Khan, H.T.A.; Raeside, R. Research Methods for Business and Social Science Students; SAGE Publications India: New Delhi, India, 2014; ISBN 8132119819. [Google Scholar]

- Poon, J.M.L.; Ainuddin, R.A.; Junit, S.H. Effects of Self-Concept Traits and Entrepreneurial Orientation on Firm Performance. Int. Small Bus. J. 2006, 24, 61–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linton, G.; Kask, J. Configurations of entrepreneurial orientation and competitive strategy for high performance. J. of Bus. Res. 2017, 70, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, H.N. Relationships between Entrepreneurial Orientation and Firm Performance: The Role of Family Involvement amongst Small Firms in Vietnam: A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Management at Mas 2017. Ph.D. Thesis, Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, S.Z.A.; Ahmad, M. Entrepreneurial Orientation and Performance of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises: Mediating Effects of Differentiation Strategy. Compet. Rev. Int. Bus. J. Inc. J. Glob. Compet. 2019, 29, 551–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Performance | Autonomy | Risk-Taking | Proactiveness | Innovativeness | Achievement | AVE | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Performance | 0.728 | 0.531 | 0.8215 | |||||

| Autonomy | 0.496 | 0.813 | 0.6611 | 0.8719 | ||||

| Risk taking | 0.52 | 0.514 | 0.726 | 0.5279 | 0.7362 | |||

| Proactiveness | 0.503 | 0.535 | 0.499 | 0.737 | 0.5442 | 0.778 | ||

| Innovativeness | 0.521 | 0.420 | 0.5408 | 0.445 | 0.769 | 0.5926 | 0.8282 | |

| Achievement | 0.629 | 0.537 | 0.4902 | 0.538 | 0.445 | 0.813 | 0.6611 | 0.8156 |

| Variables | Performance | Autonomy | Risk-Taking | Proactiveness | Innovativeness | Achievement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Performance | ||||||

| Autonomy | 0.694 | |||||

| Risk taking | 0.680 | 0.714 | ||||

| Proactiveness | 0.664 | 0.741 | 0.672 | |||

| Innovativeness | 0.722 | 0.596 | 0.732 | 0.649 | ||

| Achievement | 0.778 | 0.711 | 0.634 | 0.652 | 0.589 |

| Hypotheses | Path Coefficient (β) | t-Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Autonomy Performance | 0.033 | 0.865087 | Not Significant |

| Risk-taking Performance | 0.134 | 2.535752 ** | Significant |

| Proactiveness Performance | 0.089 | 1.965510 * | Significant |

| Innovativeness Performance | 0.143 | 2.944450 ** | Significant |

| Achievement Performance | 0.352 | 6.920889 ** | Significant |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alam, S.S.; Md Salleh, M.F.; Masukujjaman, M.; Al-Shaikh, M.E.; Makmor, N.; Makhbul, Z.K.M. Relationship between Entrepreneurial Orientation and Business Performance among Malay-Owned SMEs in Malaysia: A PLS Analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6308. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14106308

Alam SS, Md Salleh MF, Masukujjaman M, Al-Shaikh ME, Makmor N, Makhbul ZKM. Relationship between Entrepreneurial Orientation and Business Performance among Malay-Owned SMEs in Malaysia: A PLS Analysis. Sustainability. 2022; 14(10):6308. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14106308

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlam, Syed Shah, Mohd Fairuz Md Salleh, Mohammad Masukujjaman, Mohammed Emad Al-Shaikh, Nurkhalida Makmor, and Zafir Khan Mohamed Makhbul. 2022. "Relationship between Entrepreneurial Orientation and Business Performance among Malay-Owned SMEs in Malaysia: A PLS Analysis" Sustainability 14, no. 10: 6308. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14106308

APA StyleAlam, S. S., Md Salleh, M. F., Masukujjaman, M., Al-Shaikh, M. E., Makmor, N., & Makhbul, Z. K. M. (2022). Relationship between Entrepreneurial Orientation and Business Performance among Malay-Owned SMEs in Malaysia: A PLS Analysis. Sustainability, 14(10), 6308. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14106308