Market-Driven Rural Construction—A Case Study of Fuhong Town, Chengdu

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Case Selection and Data Collection

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Collection Process

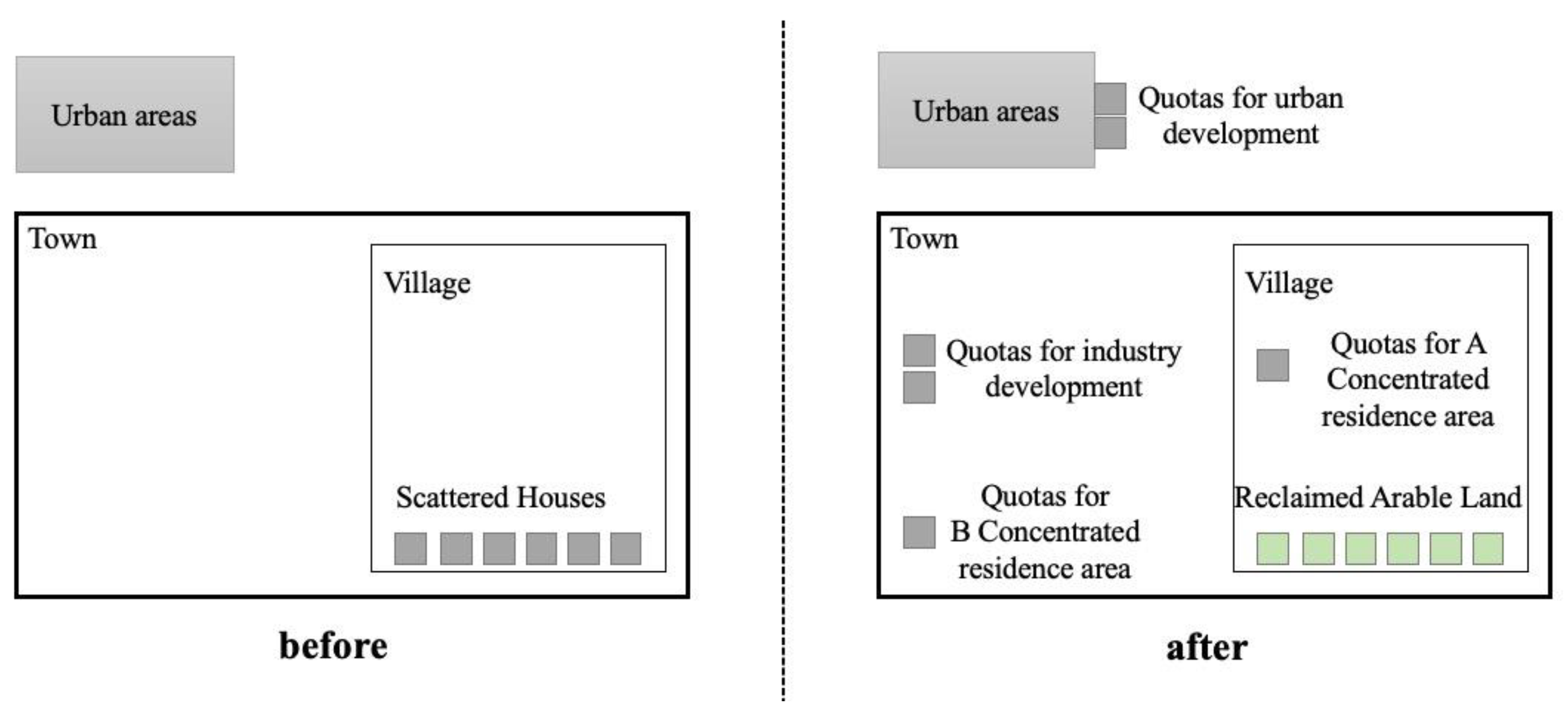

3. Institutional Background of Market-Driven Rural Construction

4. Case Study of Market-Driven Rural Construction

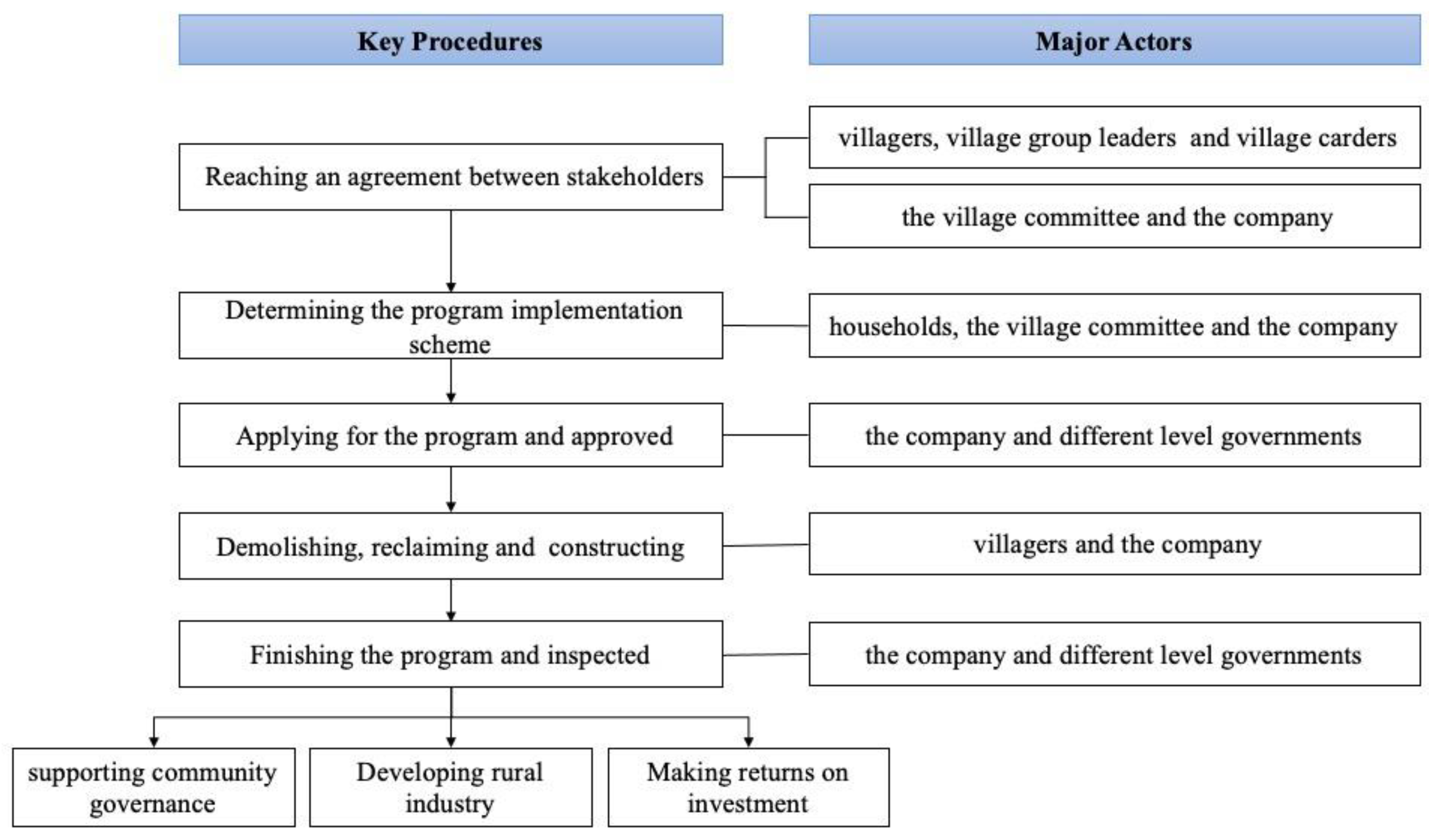

4.1. Implementation Procedures of Market-Driven Pattern

4.2. Impacts of Market-Driven Pattern on Rural Revitalization

5. Discussion

5.1. Comparison of Two Patterns

5.2. Characteristics of Market-Driven Rural Construction

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gao, J.; Wu, B. Revitalizing traditional villages through rural tourism: A case study of Yuanjia Village, Shanxi Province, China. Tour. Manag. 2017, 63, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohabir, N.; Jiang, Y.; Ma, R. Chinese floating migrants: Rural-urban migrant laborer’s intentions to stay or return. Habitat Int. 2017, 60, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Heerink, N.; Kruseman, G.; Qu, F. Do fragmented landholdings have higher production costs? Evidence from rice farmers in Northeastern Jiangxi province, P.R. China. China Econ. Rev. 2008, 19, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, E.; Banos, A.; Abrantes, P.; Rocha, J.; Kristensen, S.B.P.; Busck, A. Agricultural land fragmentation analysis in a peri-urban context: From the past into the future. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 97, 380–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pašakarnis, G.; Maliene, V. Towards sustainable rural development in Central and Eastern Europe: Applying land consolidation. Land Use Policy 2010, 27, 545–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chigbu, U.E. Village renewal as an instrument of rural development: Evidence from Weyarn, Germany. Community Dev. 2012, 43, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, D.; Wang, P. The Evolution of Western Restructuring Research. Sociol. Stud. 2014, 1, 194–216. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Patrick, K.; Kundolf, S.; Mettenberger, T.; Tuitjer, G. Rural regeneration strategies for declining regions: Trade-off between novelty and practicability. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2018, 26, 229–255. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, B. Experience and Enlightenment of modern rural construction in the suburbs of Tokyo, Japan—Taking Sanying city and Huiyuan village as examples. Shanghai J. Econ. 2007, 10, 107–112. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Xin, X. The core of China’s rural revitalization: Exerting the functions of rural area. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2019, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, Y. Building new countryside in China: A geographical perspective. Land Use Policy 2010, 27, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.; Dai, Y.; Tang, B.; Liu, J. A new model of village urbanization? Coordinative governance of state-village relations in Guangzhou City, China. Land Use Policy 2021, 109, 105500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Jiang, J.; Yu, C.; Rodenbiker, J.; Jiang, Y. The endowment effect accompanying villagers’ withdrawal from rural homesteads: Field evidence from Chengdu, China. Land Use Policy 2021, 101, 105107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.; Wang, J.; Lok, W. Redefining property rights over collective land in the urban redevelopment of Shenzhen, China. Land Use Policy 2017, 69, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J. Official relocation and self-help development: Three housing strategies under ambiguous property rights in China’s rural land development. Urban Stud. 2008, 52, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H. Land consolidation: An indispensable way of spatial restructuring in rural China. J. Geogr. Sci. 2014, 24, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Wu, Q. Incoordination between urban expansion and urban population growth and their interaction. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2016, 26, 9. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Lu, X. Driving factors of urban land urbanization in China from the perspective of spatial effects. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2021, 31, 9. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H. Political and economic consequences of government-led urbanization in central and Western China. J. Northwest AF Univ. 2016, 2, 103–109. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Kan, K. Creating land markets for rural revitalization: Land transfer, property rights and gentrification in China—ScienceDirect. J. Rural. Stud. 2021, 81, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Ravenscroft, N. Collective action in implementing top-down land policy: The case of Chengdu, China. Land Use Policy 2017, 65, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Chiu, R.L. Governing rural redevelopment and re-distributing land rights: The case of Tianjin. Land Use Policy 2018, 72, 533–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, Y.; Xu, C. Land consolidation and rural revitalization in China: Mechanisms and paths. Land Use Policy 2020, 91, 104379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Introduction to land use and rural sustainability in China. Land Use Policy 2018, 74, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.S. Research on the urban-rural integration and rural revitalization in the new era in China. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2018, 73, 637–650. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, J. Measure of urban-rural transformation in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region in the new millennium: Population-land-industry perspective. Land Use Policy 2018, 79, 595–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Long, H. The process and driving forces of rural hollowing in China under rapid urbanization. J. Geogr. Sci. 2010, 20, 876–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Selod, H.; Steinbuks, J. Urbanization and land property rights. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2018, 70, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Jia, L.; Wu, W.; Yan, J.; Liu, Y. Urbanization for rural sustainability-Rethinking China’s urbanization strategy. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 178, 580–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumford, L. The city in history: Its origins, its transformations, and its prospects. J. Aesthet. Art Crit. 1961, 67, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Hui, E.C.; Zhou, J.; Lang, W.; Chen, T.; Li, X. Rural Revitalization in China: Land-Use Optimization through the Practice of Place-making. Land Use Policy 2020, 97, 104788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Westlund, H.; Liu, Y. Why some rural areas decline while some others not: An overview of rural evolution in the world. J. Rural. Stud. 2019, 68, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J. How to promote rural revitalization via introducing skilled labor, deepening land reform and facilitating investment? China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2020; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Liu, Y. Poverty alleviation through land assetization and its implications for rural revitalization in China. Land Use Policy 2021, 105, 105418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, J. Comprehensive land consolidation as a development policy for rural vitalisation: Rural In Situ Urbanisation through semi socioeconomic restructuring in Huai Town. J. Rural. Stud. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Fan, P.; Liu, Y. What makes better village development in traditional agricultural areas of China? Evidence from long-term observation of typical villages. Habitat Int. 2019, 83, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Liu, L. Social capital for rural revitalization in China: A critical evaluation on the government’s new countryside programme in Chengdu. Land Use Policy 2019, 91, 104268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Zhang, W.; Fang, C.; Sun, H.; Lin, J. Actors and network in the marketization of rural collectively-owned commercial construction land (RCOCCL) in China: A pilot case of Langfa, Beijing. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 104990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Wang, S. Upstairs farmers and capital to the countryside: A sociological study of Urbanization. Soc. Sci. China 2015, 1, 18. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, C.; Zhou, F. “Capital to the countryside” and the reconstruction of villages. Soc. Sci. China 2016, 1, 100–116. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S. Land capitalization and rural urbanization: A survey of Beijing city’s three mode. China Open. J. 2011, 2, 17–22. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Gu, S.; Yang, W. Reflection on the five biases in the current development of Urbanization. Chin. J. Popul. Sci. 2012, 3, 2–8. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tu, S.; Long, H.; Zhang, Y.; Ge, D.; Qu, Y. Rural restructuring at village level under rapid urbanization in metropolitan suburbs of China and its implications for innovations in land use policy. Habitat Int. 2018, 77, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Qian, J.; Wang, L. Village classification in metropolitan suburbs from the perspective of urban-rural integration and improvement strategies: A case study of Wuhan, central China. Land Use Policy 2021, 111, 105748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Niu, W.; Ma, L.; Zuo, X.; Kong, X.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, W.; Zhao, M.; Xia, X. A company-dominated pattern of land consolidation to solve land fragmentation problem and its effectiveness evaluation: A case study in a hilly region of Guangxi Autonomous Region, Southwest China. Land Use Policy 2019, 88, 104115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indicator | Classification | Proportion (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Under 34 years old | 1.46% |

| 35–64 years old | 59.85% | |

| Over 65 years old | 37.96% | |

| Gender | Female | 45.99% |

| Male | 53.28% | |

| Level of education | Illiteracy | 29.93% |

| Primary school | 51.82% | |

| Junior high school | 15.33% | |

| Senior high school | 1.46% | |

| Higher education | 0.73% | |

| Type of household registration | Agriculture | 93.43% |

| Non-agriculture | 5.84% | |

| Marital status | Unmarried | 2.92% |

| Married | 84.67% | |

| Divorced | 0.73% | |

| Widowed | 10.95% | |

| Village cadre | Yes | 5.84% |

| No | 93.43% | |

| Member of CPC | Yes | 5.84% |

| No | 93.43% |

| Resettlement in the Township | Resettlement in the Village | Monetized Resettlement | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of resettlement house | High-rise apartments | High-rise apartments | single houses | No need for resettlement |

| Quantity of saved quotas | +++ | ++ | + | ++++ |

| Farming radius and costs | ++ | + | + | No farming costs |

| Living costs | +++ | ++ | + | Unchanged living costs |

| Construction costs of resettlement houses | + | ++ | Depending on construction standard | None |

| Monetized compensation | +++ | ++ | + | ++++ |

| Degree of lifestyle change | +++ | ++ | + | Unchanged lifestyle |

| Employment Type | Before the Project | Percentage | After the Project | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture | 201 | 34.07% | 57 | 9.90% |

| Non-agricultural rural employment in town | 112 | 18.98% | 135 | 23.44% |

| Non-agricultural rural employment outside town | 133 | 22.54% | 116 | 20.14% |

| Self-employment | 4 | 0.68% | 22 | 3.82% |

| Others (students, full-time mothers, etc.) | 140 | 23.73% | 246 | 42.71% |

| Total | 590 | 576 |

| Question | Answers | Proportion |

|---|---|---|

| Reasons for your and your family members’ employment changes | Changes in macroeconomic conditions | 17.78% |

| Changes in education level | 0.00% | |

| Changes in professional skills | 2.22% | |

| Changes in age | 57.78% | |

| Secondary industry introduced after project | 6.67% | |

| Development of tourist industry | 11.11% | |

| Other reasons | 4.44% |

| Income (per Capita)/RMB | Before Project | After Project | Income Gap between and after Project |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Total income | 62,719.58 | 136,958.52 | 74,238.94 |

| 1-1 Agricultural income | 5969.56 | 2216.09 | −3753.48 |

| 1-2 Operational income | 4989.05 | 20,336.23 | 15,347.18 |

| 1-3 Wage | 44,725.55 | 99,731.88 | 55,006.34 |

| 1-4 Transfer income | 4427.99 | 6512.71 | 2084.72 |

| 1-5 Property income | 248.91 | 5351.38 | 5102.47 |

| 1-5-1 House rental income | 21.90 | 221.74 | 199.84 |

| 1-5-2 Dividend income from collective economic organizations or cooperatives | 0.00 | 28.99 | 28.99 |

| 1-5-3 Rent for arable land circulation | 193.43 | 2936.74 | 2743.31 |

| 1-5-4 Insurance income | 820.12 | 3812.25 | 2992.13 |

| 2. Total expenditure | 39,874.58 | 79,619.51 | 39,744.93 |

| 2-1 Agricultural production expenditure | 4079.71 | 724.64 | −3355.07 |

| 2-2 Operational expenditure | 2153.62 | 12,443.48 | 10,289.86 |

| 2-3 Consumption expenditure | 33,589.57 | 66,982.17 | 33,392.61 |

| 2-3-1 For daily food | 13,911.45 | 30,691.30 | 16,779.86 |

| 2-3-2 For water, electricity, gas, etc. | 1806.38 | 5533.62 | 3727.25 |

| 2-3-3 For medicine | 4484.49 | 10,748.84 | 6264.35 |

| 2-3-4 For education | 4300.00 | 5063.04 | 763.04 |

| 2-3-5 For social communication (marriage, funeral, friends, etc.) | 8972.46 | 10,730.43 | 1757.97 |

| 2-3-6 For estate management | 0.00 | 11.30 | 11.30 |

| 2-4 Insurance expenditure | 285.30 | 341.91 | 56.60 |

| Before Project | After Project | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Are there street lamps on the village’s main road? | 14.60% | 85.40% | 98.54% | 1.46% |

| Is there a waste disposal station in the village? | 8.03% | 91.97% | 100.00% | 0.00% |

| Is there a sewage treatment plant in the village? | 0.00% | 100.00% | 96.35% | 3.65% |

| Are there shops in village? | 37.96% | 62.04% | 94.89% | 5.11% |

| Is there a kindergarten in the village? | 5.11% | 94.89% | 88.32% | 11.68% |

| Are there entertainment or fitness facilities in the village? | 0.73% | 99.27% | 88.32% | 11.68% |

| Are there medical and health facilities in the village? | 31.39% | 68.61% | 96.35% | 3.65% |

| Is there a bus station in the village? | 8.76% | 91.24% | 99.27% | 0.73% |

| Are there cleaners employed in the village? | 2.19% | 97.81% | 99.27% | 0.73% |

| Are there security staff employed in village? | 17.52% | 82.48% | 99.27% | 0.73% |

| Degree of Satisfaction with the Whole Implementation Process | Frequency | Ratio of Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| −2 (not satisfied) | 4 | 2.92 |

| −1 (below average) | 23 | 16.79 |

| 0 (average) | 68 | 49.64 |

| 1 (above average) | 29 | 21.17 |

| 2 (completely satisfied) | 13 | 9.49 |

| Total | 137 | 100.00 |

| Standard for Compensation (Ratio of Frequency%) | Construction Standard of Resettlement House (Ratio of Frequency%) | Allocation Standard of Resettlement House (Ratio of Frequency%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whether to ask for your family’s opinion | No | 8.03% | 21.90% | 13.97% |

| Yes, but disagree | 4.38% | 2.92% | 2.21% | |

| Yes, and somewhat agree | 61.31% | 48.91% | 49.26% | |

| Yes, and fully agree | 26.28% | 26.28% | 34.56% | |

| Decision-making method | Through the VC | 59.85% | 58.99% | 63.57% |

| Through the Village Meeting | 7.30% | 7.91% | 15.71% | |

| Through the government or company | 11.68% | 15.83% | 7.14% | |

| Do not know how to make decisions | 21.17% | 17.27% | 13.57% |

| Key Issues | Ratio of Frequency (%): Which Rules did your Household Know About? (Multiple Choice) | Ratio of Frequency (%): Which Rules Were You Notified or Informed About? (Multiple Choice) |

|---|---|---|

| Standard for resettlement and compensation | 87.59% | 24.09% |

| Construction standard of resettlement house | 68.61% | 22.63% |

| Land property rights adjustment | 35.04% | 8.76% |

| Land reclamation | 56.20% | 9.49% |

| Allocation standard of resettlement house | 74.45% | 13.87% |

| Funding use | 0.00% | 2.19% |

| Project supervision | 5.84% | 3.65% |

| Know little about these | 10.22% | 75.18% |

| Frequency | Ratio of Frequency (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Does the company encroach on your rights? | Yes | 72 | 52.55 |

| No | 65 | 47.45 | |

| Does the local government (or investor) encroach on your rights? | Yes | 51 | 37.23 |

| No | 86 | 62.77 | |

| Do the village cadres protect your rights? | Yes | 61 | 44.53 |

| No | 76 | 55.47 | |

| Key Issues | Government-Led Pattern | Market-Driven Pattern |

|---|---|---|

| Industry development | Neglects rural industry development | Emphasizes introduction of small and medium-sized or labor-intensive enterprises |

| Population agglomeration | Has little impact on rural population outmigration | Makes villagers more concentrated and attracts migrant workers back |

| Land acquisition | Compulsory land expropriation and rural land is changed to state-owned land | Land use rights are transferred and land is still owned collectively |

| Fundraising | Land transfer fees from estate developers and land mortgage loans | Market capital |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, Y.; Liu, J.; Kang, X. Market-Driven Rural Construction—A Case Study of Fuhong Town, Chengdu. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6014. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14106014

Zhou Y, Liu J, Kang X. Market-Driven Rural Construction—A Case Study of Fuhong Town, Chengdu. Sustainability. 2022; 14(10):6014. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14106014

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Yujun, Jingming Liu, and Xiang Kang. 2022. "Market-Driven Rural Construction—A Case Study of Fuhong Town, Chengdu" Sustainability 14, no. 10: 6014. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14106014

APA StyleZhou, Y., Liu, J., & Kang, X. (2022). Market-Driven Rural Construction—A Case Study of Fuhong Town, Chengdu. Sustainability, 14(10), 6014. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14106014