Abstract

The construction of China’s high-speed rail has been arousing controversy for the possibility of exacerbating regional imbalance. This paper provides an empirical analysis based on the panel data of 276 prefecture-level cities during 2007–2018 to explore the authenticity of this inference. The panel threshold model is adopted to investigate whether the economic growth becomes stronger and more equal among China’s cities under the impact of the rapidly expanding high-speed rail network by taking per capita gross domestic product (pGDP) as the threshold variable. To fully explore the dynamic function, we incorporate three progressive indices to measure the role of cities in China’s high-speed rail network: the existence of high-speed rail, the number of lines, and the betweenness centrality of the city in the entire network. The result shows that high-speed rail can promote economic growth and that there is a threshold effect in this process. Specifically, cities with higher pGDP can benefit more from high-speed rail. Another significant conclusion can be drawn that high-speed rail can intensify regional disparities, yet the marginal economic gap tends to decline as the high-speed rail network gets more optimized. Meanwhile, this study recognized nine circle-like high-speed rail urban agglomerations based on empirical results, reflecting the polycentric developing pattern of China.

1. Introduction

In China, an adequate and mature high-speed rail system has come into being, despite a relatively late beginning in the 1990s. China’s high-speed rail has grown from isolated lines into the wide coverage of the “Eight Vertical and Eight Horizontal” network, deeply affecting society with its advantages of higher levels of efficiency, comfort, and safety, as well as lower labor costs and overall long-term emission reductions [1,2]. However, there has always been public opinion about boycotting the planning and construction of more high-speed rail lines for two main reasons. First, whether the high cost of building and maintaining the relevant facilities can be covered by the economic and social benefits produced by high-speed rail remains uncertain [3]. Second, it is highly possible for the regional development level to become less balanced for high-speed rail to play a vital role as a corridor between cities. Specifically speaking, high-quality resources tend to flow into core cities along rail routes, leading into negative influences for non-core cities, which are generally less developed [4].

The opening of Shanghai–Kunming High-Speed Rail in 2016 officially marked the formation of the “Four Vertical and Four Horizontal” high-speed rail network, symbolizing the arrival of the new “network era”. In China, the high-speed rail lines will be 38,000 km in total by 2025. This network can largely ameliorate accessibility, as all cities with more than half-a-million populations and all provincial capitals (except for Lhasa) will be linked by high-speed rail lines [5]. The “time–space convergence” and radiation effect generated by networked high-speed rail improves the accessibility and connectivity between cities on a larger scale, which provides both opportunities and challenges for regions [6,7]. It is generally believed that the spatial developing pattern of China can be reshaped, as the economic impact of high-speed rail under this networked pattern would be more profound and complicated [8]. China declared complete victory in the war against poverty in 2020, followed by declaring the achieving of common prosperity as a significant mission in the future. Thus, this study attempts to examine whether there are positive effects of high-speed rail, especially in the networked pattern, on economic growth, and regional equity, which would be of great value for the future planning of high-speed rail in China.

Based on the sample of 276 prefecture-level cities from 2007 to 2019, our study successfully proved the non-linear driving effect of high-speed rail on economic growth and reasonably made an inference about its influence on regional equity by using the panel threshold model. There are three main contributions of our study. Firstly, three progressive indices including the presence of high-speed rail, the number of lines, and the centrality of cities in the railway network are adopted to investigate the dynamic effect of high-speed rail on the economy. Secondly, it is worth noting that the marginal gap between cities shrinks as the high-speed rail grows into a higher-quality network, while the absolute gap keeps widening along with the burgeoning of this transportation infrastructure. Thirdly, economic geography methodology is also applied to show the dynamic features of the high-speed rail, network and nine high-speed rail urban agglomerations are recognized for the reference of future planning.

This paper is organized as follows: The next section reviews the literature about the economic impact of high-speed rail. In Section 3, we bring about our studying hypotheses by expounding the mechanism on the interaction between high-speed rail, economic growth, and regional economic equity. We then present the empirical methodologies as well as the data adopted in Section 4 and Section 5, followed by the empirical results in Section 6. Further analysis using the economic geography mapping method are made in Section 7. Finally, we summarize the main discoveries and put forward related policy implications.

2. Literature review

2.1. Transportation Infrastructure and Economic development

The impact of transportation infrastructures on economic growth has been under spirited discussion with a number of valuable conclusions [9]. Overall, transportation infrastructures can basically promote economic growth, noticeably, as a catalyzer [10]. Apart from the growth, labor productivity and total factor productivity can also improve under the influence of the stock of infrastructures [11]. It is commonly believed that the improvement of transportation infrastructure itself, such as high-speed rail, cannot always stimulate regional economic growth, as complementary factors are necessary for transportation infrastructures to play their role as the economic growth driver [12,13,14]. Therefore, the inquiry about the heterogeneity of the effect of high-speed rail is indispensable for us to understand the externalities of high-speed rail thoroughly. Cities with different development levels, locations, and populations are likely to make vary degrees of profit from the high-speed rail network they belong in [15,16]. The externalities even differ in the various periods of the lifecycle of high-speed rail, typically including stages of planning, construction, maintenance, and disposal [17]. In addition, the reaction of urban actors after the opening of transport infrastructures can affect the level of profit gained from transport network as well [10].

2.2. High-Speed Rail, Economic Growth, and Regional Equity

High-speed rail, as a burgeoning and networked transportation infrastructure, is generally believed to have a positive driving effect on economic growth due to its multiplier effect in investment and the feature of reducing the spatial–temporal distance between cities [18,19]. High-speed rail can also facilitate regional economic convergence because of the spill-over effect [20], which may vary between regions composed by cities with different levels of connection [21]. Networked patterns of high-speed rail have become the mainstream in countries with large territorial areas and sufficient population sizes in view of the comparative advantages of different means of transportation [22]. Significant improvements in connectivity and accessibility due to high-speed rail networks have been generally proved [6,23]. Apart from those direct bonuses from high-speed rail networks, the socio-economic return is also worth noticing. Due to the transition from separated lines to an integrated network, the two opposing forces of agglomeration and dispersion get more significant and thus effect China’s economic spatial structure [24]. In addition, network externality, overall social welfare, and regional productivity can also get promoted [25,26,27].

However, the economic effect of high-speed rail is more controversial for the possibility of deepening regional inequity [28,29]. Cities with more population and higher GDP tend to obtain more increases in centrality as the network gets denser [23]. In China, cities in central and eastern areas would benefit more from the high-speed rail network due to their relatively low travel times and high populations [6]. Therefore, only with scientific planning and reasonable financing can high-speed rail effectively boost China’s economic growth and reshape China’s spatial economic pattern [16].

In this paper, we would focus on the characteristic of non-linearity in this process, which has not been fully considered, in order to further evaluate the impact of high-speed rail on economic growth and regional equity. Furthermore, most related studies were carried out merely from the perspective of the existence of high-speed rail or the number of rail lines instead of a network, which would cause deviation from reality and possible bias in the empirical results. Therefore, three indices were adopted to measure the development level of high-speed rail, including the presence of high-speed rail, the number of lines, and betweenness centrality corresponding to different statuses, from the beginning of construction to the extensive coverage of high-speed rail.

3. Theoretical Analysis and Hypothesis

3.1. High-Speed Rail and Economic Growth

High-speed rail influences the regional economy mainly by two means, direct and indirect. The direct impact is primarily characterized by the tremendous multiplier effect of investment on high-speed rail [30,31]. Every period of the full life cycle of high-speed rail has vast demand for labor, capital, and technology, which require a large number of investments. Firstly, the construction of high-speed rail fueled the formation of related upstream, medium-stream and downstream industries in node cities in order to lower the cost to exchange goods, labor, and ideas [32]. In detail, building materials industries such as the steel industry, extractive industry, and smelting industry are constantly requisite for every period in the life cycle of high-speed rail, as well as the mechanical parts processing industry and infrastructure equipment industry [33]. Secondly, the benefits of job creation can enhance resident income and furthermore promote demands in consumption, which would stimulate the development of local industries. As a result, the improvement in the diversity and advanced level of the industrial structure can attract more capital investment and continually create more jobs as a virtuous circle, evoking economic growth in the region around the node city [34].

The indirect effect of high-speed rail on economic growth can also be embodied in two aspects. On the one hand, high-speed rail significantly reduces the spatial–temporal cost of traveling and brings about the accessibility gains of cities in the high-speed rail network [35]. Improved accessibility has a positive effect in the flow of production factors, including labor [36], capital, [37] and technology [38], which also makes a great difference for the decision maker of the firm location [39]. Marginal output is generally high in the core cities of the high-speed rail network. Thus, the market potential of core cities, related closely to the level of nominal wages as well as the purchasing and investment demand [40], is about to increase for the geographical concentration of high-quality factors in those cities [41]. Therefore, core cities can earn high-quality developing conditions and momentum for economic growth because of the high-speed rail network. On the other hand, the impact of high-speed rail is beneficial to the entire region around the node city for the existence of the spatial spill-over effect [34], which becomes even more significant as the network gets more optimized. With the radiation effect of networked high-speed rail, the markets centered in the core cities get extended and metropolises act as growth polarities in China. It should be noted that this function of regional integration may not show itself in the short term after the network comes into being because of the possible “corridor effect” [42].

Based on the analyses above, the first hypothesis (H1) is put forward: high-speed rail does promote regional economic growth.

3.2. Heterogeneity in the Economic Impact of High-Speed Rail

It has been widely acknowledged that the socio-economic impact of high-speed rail varies in cities with different resources endowment, which is reflected by the geographical location. The marginal influence of high-speed rail, a public facility, relies heavily upon local infrastructure condition and policy environment [14]. Take industries as example. The specialization or diversified trend of industrial structure, whether was driven by construction demands or redistribution of premium factors, depends largely on the government policy, monetary support from finance institution and the scale of professionally trained labor force. Yangtze River Delta Urban Agglomeration is typical in the efficient guidance of policy. It is clear that the preferential policies in this region such as local protectionism and environmental regulations can significantly promote regional equity and high-quality development [43]. More developed city can provide more fertile soil for high-speed rail that is, so to speak, the regional economic engine to fuel a new round of economic growth.

Therefore, we bring about the second hypothesis (H2): the positive effect of high-speed rail on economic growth is more significant in cities that are more developed.

3.3. High-Speed Rail and Regional Equity

It is generally believed that high-speed rail would lead to the spatial redistribution of accessibility, and then result in the change in the relative status of cities in the transportation network [44]. At the beginning of the opening of high-speed rail, non-core cities that are normally less developed tend to suffer from the loss of production factors due to the agglomeration of a high-quality labor force and technology along rail lines in core cities, which can lead to the trend of enlarging the regional economic gap [43]. However, we argue that the distribution pattern of factors would have the tendency to be converted from aggregation to diffusion due to the networked shape of high-speed rail. In consequence, the negative influence of the siphonic effect in non-core cities gradually weakens.

We think the reasons for this phenomenon lie in the spatial reallocation of labor and industries. In the mid-long term, since the construction of high-speed rail, technology-intensive industries and knowledge-intensive industries will dominate in core cities while labor-intensive and resource-intensive are forced to migrate to surrounding less-developed areas for cheaper production factors [45]. At the same time, lower-skilled workers are inclined to move into regions with lower living costs, non-core cities in other words, as the promotion in location advantage makes it more expensive to live in core cities. Optimizing the matching relationship of labor and industry in these underdeveloped cities is profitable for local lower-end industries. Therefore, the coupling of human capital and job will appear at both core and non-core cities over time, leading to a boost in income, consumption, and investment, and a reduction in regional imbalance. The prominent role of high-speed rail on facilitating urban specialization is expected to promote regional integration as well as fuel the dynamic transition of China’s economic development into a multi-polar pattern.

Hence, the last hypothesis (H3) of our study is drawn that economic growth in different cities tends to be more equalized in pace with the networked expansion of high-speed rail.

4. Measurement of High-Speed Rail

Social network analysis (SNA) is a quantitative analysis method based on mathematic and graph theory, aiming at describing the structural properties of networks [46]. A series of formal models of SNA have been created since the last century to analyze the actors, and relationships between them, under a particular social circumstance, and have been applied on empirical studies in economics, geography, anthropology, psychology, business organization, and other fields by plenty of social scientists. Social network is an umbrella term covering a wide range of forms, in which nodes can stand for objects, events, people, and even behaviors, as well as the social relationship between them. SNA can help us to understand when, why, and how these nodes function intuitively and precisely [47]. How we analyze the structural features of China’s high-speed rail by adopting SNA starts with the networked abstraction of high-speed rail by regarding its cities and rail lines as nodes and edges.

The overall “density” of a network and the relative “centrality” of nodes within a network can be measured using the values of nodes and links based on graph theory [48]. To examine the structural characteristics of cities in the high-speed rail network, a centrality measurement is appropriate to be employed to reflect the structural properties of nodes. There are three most frequently used centrality indices in SNA, namely degree centrality, betweenness centrality, and closeness centrality [49]. The first measure, based on the degree of points, indicates the dominance of a node simply up to the number of other nodes directly linking to it. Betweenness centrality possesses a more complex implication of the potential to influence on the process we study on [50] (we may call this a potential “hub level”). The last measurement in the name of closeness centrality is derived from the distance between two nodes. After synthetically considering on the meaning and calculation complexity, betweenness centrality (BC) is chosen to represent the level of the high-speed rail network. According to Freeman (1977) and Brandes (2001), relative BC is calculated in the following form [50,51]:

where represents the betweenness centrality of city , stands for the number of nodes in the network, and is the amount of all the shortest paths from city to city , among which there are paths passing city . This is a standardized betweenness centrality to ensure comparability between cities. The importance of a city, reflecting the city’s ability to control or influence all other nodes in the network, is approximately in proportion to the value of BC.

The timetable of high-speed rail lines is available on the 12306 China Railway Website (12306.cn). In this paper, we classify the year every line belongs to by the time point when it is put into use. If a line goes into service before June in one year, it ought to be regarded as the line of the current year, otherwise it should belong to the next year. We divided 276 prefecture-level cities into three groups according to their BC by two segmentation points of 1 and 10. Figure 1 and all the figures in the following context are produced with Adobe XD. Figure 1 exhibits the spatial distribution of cities with different levels of BC, as well as main lines in the “Four Vertical and Four Horizontal” high-speed rail network, from which we can draw some meaningful conclusions. The most distinct phenomenon we can observe from the picture is that the high-BC cities are arranged basically in a band structure along eastern coastal areas and the Yellow River, corresponding to the location of the Beijing–Shanghai High-Speed Railway and Xuzhou–Lanzhou High-Speed Railway, two major arteries in the “Four Vertical and Four Horizontal” network. Node cities along those lines are likely to have a comparative advantage in location, geographically and economically, so that they can play a part as key hubs in the network.

Figure 1.

The spatial distribution of betweenness centrality of cities and “Four Vertical and Four Horizontal” high-speed rail network.

5. Methodology, Data, and Variables

5.1. Economic Modeling

For the purpose to examine the comprehensive effect of high-speed rail on economic growth, we firstly use the panel data model as follows to carry out the empirical analysis. Equation (2) is based on ordinary least square (OLS) estimator, which has been widely applied to analysis on the economic impact of high-speed rail and other transportation infrastructures [52,53,54]. Other factors which can also influence economic growth are contained in the model as control variables, namely employment, finance, industrial structure, innovation capacity, and urbanization.

where is the annual gross domestic product of each prefecture-level city, which represents the economic level of the sample and is the explained variable in the empirical part of this paper. indicates the core explanatory variable of this paper, representing the level of high-speed rail development, and contains sub-variables at three levels: availability of high-speed rail (), number of high-speed rail lines (), and betweenness centrality of the high-speed rail network (). reflects the set of control variables. and are the estimated coefficients of the corresponding variables, which represent the marginal influence of every explanatory variable on explained variable. , , and are individual-fixed effects, time-fixed effects, and random disturbance terms, respectively.

The effect of high-speed rail on economic growth varies with the distinction in developing level between regions. Therefore, the selection of a non-linear model can reflect this function more scientifically. In our study, a panel threshold model is developed to investigate the jumping character of the impact of high-speed rail on economic growth [55], from which the converging trend of this effect is additionally revealed. The single-threshold model was developed by Hansen (1999), which is given by

where indicates gross domestic product, represents all explanatory variables. represents the threshold variable, which has been selected as per capita gross domestic product in this paper and will be further explained in the next section. reflects the residuals. γ is the threshold value and I(·) is the indicator function dividing the model into two regimes, which is determined by the threshold variable . To be specific, when , the and ; when , and . α and β are the parameters to be estimated by OLS under the two regimes, respectively. We firstly estimate whether there is threshold effect, that is the structural break in the relationship between high-speed rail and economic growth [56]. If so, the correlation between core variables in different threshold ranges, which is embodied by the significance and value of α and β, is consequential to be observed and explained. The multiple threshold model is set up in a similar way to do estimates and explore the heterogeneity of the correlation between variables within different threshold ranges. For instance, the double threshold model is given below:

where the two thresholds are in the order of . , , and denote the marginal effect of high-speed rail on economic growth in the low, high, and medium regimes of per capita gross domestic product.

5.2. Data and Variables

The data adopted for the empirical analysis of this paper are the panel data of 276 prefecture-level cities in China from 2007 to 2018. The data on high-speed rail-related variables are collated from the 12306 China Railway Website (12306.cn), and the data on other economy-related variables are obtained from the China City Statistical Yearbook and the official websites of the statistical bureaus of each prefecture-level city. As we stated in Section 3, high-speed rail lines opened before June (including June) of the current year are counted as new lines in this year, while those opened after June are counted as lines opened in the next year. The following variables are considered in both equation:

- (1).

- Explained variable: gross domestic product (). covers the achievements of all productive activities in a region over a certain period, which can reflect the level of regional economic growth most comprehensively and reasonably;

- (2).

- Threshold variable: per capita gross domestic product (). , as a relative quantity compared to the absolute quantity of , is more suitable for cross-sectional comparisons between regions and can be adopted to measure the level of regional development;

- (3).

- Explanatory variables: the presence of high-speed rail (), which is a dummy variable of 0–1, the number of high-speed rail lines (), and the betweenness centrality () of the cities in high-speed rail network;

- (4).

- Control variables: It is of great necessity to control the impact of other possible factors that are related to the explained variable to guarantee the accuracy and reliability of our estimation. According to previous studies we mentioned, five control variables are considered as follows: Employed population () in each prefecture-level city is used to characterize the level of employment, and local financial revenue () is used to characterize the scale of government. The ratio of the added value of the tertiary industry to the added value of the secondary industry is used to measure the advanced level of industrial structure (), while the science expenditure () is used to measure the innovation capacity of the city. Finally, the population urbanization rate () is used to measure the level of urban–rural coordination.

The descriptive statistics of above variables are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics.

6. Results

6.1. Baseline Regression

In this sub-section, the estimation result of Equation (2) is presented in Table 2, aiming at gaining a preliminary insight into the economic effect of high-speed rail. Models (1), (2), and (3) correspond to the results of the models with the presence of high-speed rail, the number of lines, and the betweenness centrality, respectively, as the core explanatory variables.

Table 2.

Baseline regression results.

In models (1)–(3), the coefficients of , , and are all significantly positive. Specifically, the results of Model (1) indicate that the opening of high-speed rails can obviously contribute to economic growth; Model (2) shows that the increase in the number of lines based on the opening of high-speed rails can strongly contribute to the economic growth of cities at the stations; and Model (3) illustrates that the increased hub position and influence of cities in the high-speed rail network can also lead to economic growth. These results reveal the fact that high-speed rail has a positive effect on economic growth in principle, and thus Hypothesis 1 is initially certified. However, the difference in the coefficients of , , and in the value of 0.0138, 0.0293, and 0.00177, respectively, indicates the heterogeneity in the measure of high-speed rail development. The increase in the number of lines has the most significant effect on economic growth, followed by the presence or absence of the opening of high-speed rails. The overall pull-up effect of the increase in the centrality of the network on economic growth is slightly weaker than the first two. The possible reason behind this heterogeneity is that the radiation effect of the high-speed rail network has led to a gradual change from a concentration to a spreading pattern of production factors, while the pattern of economic growth has gradually changed from pole growth to balanced regional growth. As a result, the growth benefit gained from network development will gradually slow down. Moreover, the optimization of economic structures between regions will substitute “rapid growth” as the new developing mode, which is consistent with the current trend of high-quality economic development in China.

The regression results of the control variables prove that the scale of government, the level of employment, and the advanced level of industrial structure can also positively affect local economic growth. The financial budget of government can contribute to the economy because it can, to a certain extent, directly drive the increase of gross domestic product on the one hand, and indirectly meet the social demand for public goods and services on the other hand to achieve positive externalities [57]. The level of the employed population can directly contribute to the development of industries and the income levels of residents and promote the increase of economic aggregates, while the improvement of the industrial-advanced level can enhance labor productivity, which is the intrinsic demand and impetus of economic growth [58]. It is also revealed that the optimizing of employment and industry and the coupling of development between the two are an efficient way to achieve high-quality economic growth.

6.2. Threshold Model

Based on the conclusions of the baseline regression, in this paper, the non-linear characteristics of high-speed rail for economic growth are estimated with the threshold model, and thereby an inference is made regarding whether the planning and construction of high-speed rail can promote a more balanced regional economic structure. A double-threshold panel model in the form of Equation (4) is adopted for this part of the analysis. For the specific regression settings, the trimming proportion of each threshold is 0.05, and the number of bootstrap replications is 300. With as the threshold variable, Table 3 and Table 4 report the threshold estimators, the threshold effect, and the outputs of regression.

Table 3.

Test for threshold effects.

Table 4.

Threshold estimates.

The results in Table 3 indicate that there is a double threshold effect for the impact of high-speed rail on economic growth considering three progressive levels of high-speed rail-related variables. In Model (4), the two thresholds for per capita are 87,153 and 76,653: the coefficient of is 0.00487 when the level of is less than CNY 76,653; when is within a range of CNY 76,653–CNY 87,153, the coefficient of increases to 0.0262 and becomes more significant. When is greater than 87,153, the estimated coefficient of continues to go up to 0.0662 and remains at a high level of significance. The results of Model (5) demonstrate a similar trend when the number of high-speed rail lines is taken as the core explanatory variable. As increases, the coefficient of line increases in the three intervals divided by the thresholds of = 54,565 and = 87,153 to 0.00931, 0.0215, and 0.0475, and all are significant at the 0.01 level. In Model (6), the coefficient of also enhances with elevated : when < 44,029, the regression coefficient of is 0.0001 and has a low significance level; when 44,029 < < 87,153, its coefficient rises to 0.00116 and becomes significant; when >87,153, the coefficient of bc continues to increase significantly to 0.0048. In addition, the direction and significance of the regression results for the control variables are also accordant with the results of the baseline regression, corroborating the robustness of the regression.

The implication of those three indices we adopted to measure the developing level of high-speed rail is incremental, which can reflect the dynamic effect of the different arranging dimensions of high-speed rail on the regional economy. By diving into the results above, the following conclusions can be summarized to offer a valuable reference for future rail planning:

- (1).

- All three regressions significantly proved that the opening of the high-speed rail has an obvious pull-up effect on the economic development of cities at diverse economic levels embodied with . However, the higher the level of economic development of the city, the more conspicuous this driving effect will be, suggesting that both hypotheses 1 and 2 are convincing. Indeed, economic growth is driven by a wide and complex set of factors that depend on the collective functioning of government, industries, universities, financial institutions, and individuals. As a transport infrastructure, the role of high-speed rail is highly dependent on the original conditions of the region. More developed cities definitely possess better infrastructures, more open access to capital, and more superior policy support. Thus, the investment and high level of labor resulting from the construction and operation of high-speed rail in these areas will function better in the economic system and promote economic growth consequently, which is accordant with the conclusions from existing studies [6,23];

- (2).

- The second threshold in models (4)–(6) are all 87,153. As the high-speed rail system evolves from opening to line establishment and networked coverage, the first threshold keeps declining from 76,653 to 54,565 and 44,029, respectively. For convenience in narrating, cities are divided by the two thresholds into three groups, from high to low as the first, second, and third classes. An interesting implication of the results is that more and more less-developed cities will move from the third class to the second class when the emphasis transforms from the existence of station to number of lines and status in network. Furthermore, the ability of these cities to gain profit from the high-speed rail bonus will relatively improve with the optimization of the network. In other words, the formation and improvement of the high-speed rail network will be more helpful to less-developed regions. The negative effects of the siphon effect will be gradually eliminated as the centrality of cities increases, which contributes to regional integration;

- (3).

- It is inspiring that the difference in the benefit from the economic effect of high-speed rail between the classes is gradually decreasing from (4)–(6). In Model (4), the coefficient for the second class of high-speed rail variables is 0.04 less than the first class, and the third class is 0.0213 less than the second class. The two core coefficients are 0.026 and 0.0122 in Model (5) and are reduced to 0.0036 and 0.0011 in Model (6). As we can see, the opening and operation of high-speed rail, no matter how we measure it, always widens the economic gap between cities of different developing levels in the region. However, as the density of lines increases and the network becomes more compact, the difference in marginal growth between less-developed and developed regions will gradually lessen. We must honestly admit the fact that high-speed rail does temporarily intensify regional economic imbalance, but the diminishing tendency of this adverse effect as the network advances needs to be made aware of as well. Kim (2015) held a similar view point that regional inequality would decline in general in the later stages of high-speed rail extension [28]. In the long term, the negative influence of the siphon effect and corridor effect will no longer exist hopefully, and Hypothesis 3 will be proved.

Conclusions (2) and (3) both suggest that the trend towards regional economic polarization due to factor agglomeration caused by high-speed rail will diminish as the networked pattern comes into being. This is mainly because the radiating effect of the network has strengthened the connection between cities and the economic activities are no longer mainly confined within cities and provinces but have expanded to a broader range of urban agglomerations. The flow of factors within such urban agglomerations often relies on high-speed rail networks, leading to the constant transfer and takeover of industries between core and non-core cities [59], as well as a redistribution of labor. Based on the comparative advantage of every city, an urban agglomeration structure with a specialization of labor, regional integration in other words, gradually becomes the dominating developing trend.

6.3. Further Analysis

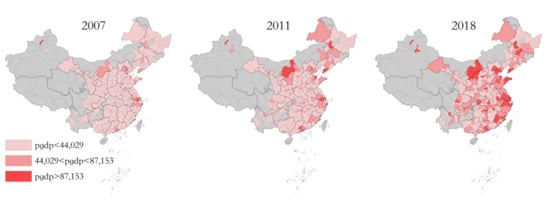

In the background of the “Eight Vertical and Eight Horizontal” high-speed rail network, the characteristics of the high-speed railway network should be explored further. Therefore, this section will analyze the regression results in Model (6) by dividing the 276 prefecture-level cities into three groups according to two thresholds of , mapping the dynamic evolution of the spatial distribution of the three groups of cities during the period 2007–2018.

In Model (6), the two thresholds are = 44,029 and = 87,153. When the per capita gross domestic product of a city is less than CNY 44,029, the high-speed rail network has a less significant effect on the economic growth of the city; when the per capita gross domestic product is within the range between the two thresholds, the development of the high-speed rail network will generally have a pull-up effect on the economy of these cities; and when the per capita gross domestic product is greater than CNY 87,153, the network of high-speed rails will significantly boost the economic growth of cities. The year 2011 saw the opening of the Beijing–Shanghai High-Speed rail, which runs through important economic zones, such as the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei Urban Agglomeration, the Shandong Peninsula, and the Yangtze River Delta, and has become an important north–south trunk line that is most capable of improving the accessibility of the regions along its route in the “Four Vertical and Four Horizontal” network (Jiang Bo et al., 2016). Its opening marked the beginning of the formation of China’s high-speed rail network to a certain extent. Therefore, in addition to the two sample starting years of 2007 and 2018, we also mapped the spatial distribution status of cities in 2011 for a comparative analysis (Figure 2). The lightest area is for cities with a per capita gross domestic product of less than CNY 44,029, the darkest area is for cities with a per capita gross domestic product of more than CNY 87,153, and the cities with an intermediate color have a per capita gross domestic product between the two thresholds.

Figure 2.

Spatial distribution of threshold groupings of 276 prefecture-level cities in China in 2007, 2011, and 2018 (from left).

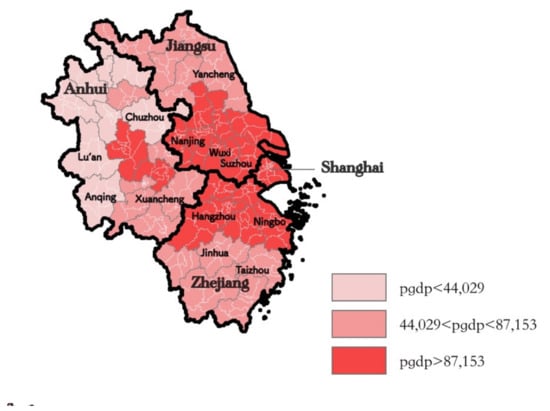

As can be seen in Figure 2, from the beginning of the construction of the high-speed rail to the basic formation of the “Four Vertical and Four Horizontal” network, a nationwide circle-like structure centered on the economic growth poles of node cities (i.e., cities with > 87,153) has gradually emerged. Taking the Yangtze River Delta and its surrounding areas as an example, the region has formed such structures centered on the cities of Shanghai, Nanjing in Jiangsu, and Hangzhou in Zhejiang in 2018, as shown in Figure 3. Five developed cities adjacent to Shanghai including Nanjing, Suzhou, Hangzhou, Ningbo, and Wuxi form the inner-core of the circle, which are the first beneficiaries of the high-speed rail network. Cities on the periphery of the inner-core such as Jinhua, Taizhou, Xuancheng, and Yancheng compose the second circle, enjoying the spill-over bonus of high-quality factors brought by the axial overflow along the high-speed rail from the central growth pole; the outermost cities such as Chuzhou, Anqing, and Lu’an are far from the central growth poles and are relatively backward in economic development, hence the economic externalities brought about by the high-speed rail network are not significant. Besides, most of the outermost cities are not part of Integrated Demonstration Zone of the Yangtze River Delta and cannot enjoy the government’s supportive policies on industries, infrastructures, ecological environment, and public services in the region, which reflects the essentiality of governance for the role of high-speed rail. This circle structure further supports the radiating effect of the economic effect of the high-speed rail network.

Figure 3.

Spatial distribution of threshold groupings in Yangtze River Delta, 2018.

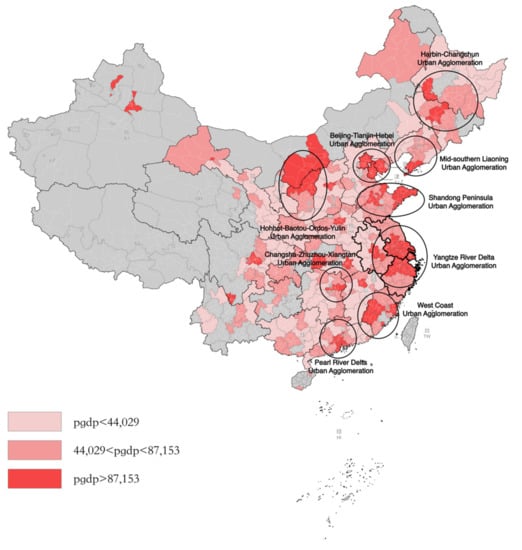

In 2007, prefecture-level cities across China were generally at a low level of development. The economic impact of high-speed rail on most cities was not significant, with only the Yangtze River Delta, Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei, and the Pearl River Delta regions being able to gain profit from it, showing a monocentric growth pattern overall. With more lines constructed and the high-speed rail network gradually get denser, high-speed rail urban agglomerations with cities in the first class as the central circle gradually appear nationwide, and the economic spill-over effect due to the networked radiation becomes more and more obvious. This developing pattern has already shown up after the opening of the Beijing–Shanghai high-speed rail in 2011. When the “Four Vertical and Four Horizontal” network was completed by 2018, a polycentric circle development pattern can be considered to have formed. As can be seen from the Figure 4, nine city agglomerations, including the Harbin–Changchun Urban Agglomeration, the Mid-Southern Liaoning Urban Agglomeration, the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei Urban Agglomeration, the Shandong Peninsula Urban Agglomeration, the Hohhot–Baotou–Ordos–Yulin Urban Agglomeration, the Yangtze River Delta Urban Agglomeration, the West Coast Urban Agglomeration, the Pearl River Delta Urban Agglomeration, and the Changsha–Zhuzhou–Xiangtan Urban Agglomeration have already owned the circle-like features as high-speed rail urban agglomerations that are capable of acting as growth poles in the high-speed rail network to realize the radiation of high-quality factors and promisingly drive the economic growth of surrounding areas to achieve regional integration.

Figure 4.

Nine typical high-speed rail urban agglomerations in China.

6.4. Robustness Test

To validate the reliability of the above regression results, this paper adopts two methods for robustness testing: (1) Due to the high level of economic development of the municipalities directly under the Central Government, those municipalities are excluded from the sample of empirical study; (2) considering the time lag of the effect of high-speed rail, the explanatory variables , , and are treated as one-period lags. The above two methods are adopted to observe whether the regression results after treatment are consistent with the previous section. Table 5 and Table 6 show the results of Equation (4) after excluding the municipalities directly under the Central Government and the core explanatory variables lagged by one period, respectively. The coefficients of the core explanatory variables remain significantly positive after the treatment and tend to rise with the increase in per capita gross domestic product. Although the betweenness centrality in models (9) and (10) only has a single threshold effect, the difference between the coefficients still decreases gradually with the start of high-speed rail to the formation of the network: the overall trend of the results of this part of the test is consistent with the previous section, which can prove that the empirical results of this paper are reliable.

Table 5.

Threshold estimates without municipalities.

Table 6.

Threshold estimates after lag treatment.

7. Discussion and Conclusions

Should China continue the construction of high-speed rail? If so, how should the high-speed rail network be arranged? These questions have been under controversial debates for the conflict between the financial return and social benefits of high-speed rail. Our study significantly provides a reasonable answer from the perspective of economy and geography. Based on annual panel data of 276 prefecture-level cities in China from 2007 to 2018, this paper combines social network analysis and panel threshold models to analyze the effects of high-speed rail on economic growth at three dynamic levels, including the presence of high-speed rail, the number of high-speed rail lines, and the centrality of the cities in high-speed rail network. We have successfully confirmed the function of the high-speed rail as the catalyzer of economic growth but also the implication of its role to narrow the marginal gap between regions. In combination with cartography, nine “high-speed rail urban agglomerations” are originally recognized and put forward, in which the developing pattern is dominated by hub cities. This kind of agglomeration can take maximizing advantage of the radiation effect of the high-speed rail network to avoid the negative influence of the corridor effect and approach regional equity.

Three implications could be drawn from the empirical and mapping analysis. First, the opening of high-speed rail, the arranging in rail lines, and the improvement in network centrality can both boost a city’s economic growth, while the economic effect from increased network centrality is weaker than the first two. This is mainly because the radiation effect of the high-speed rail network will promote the diffusion of factors rather than the agglomeration, for which the structural equilibrium pattern of economic growth tends to dominate. It is worth noticing that the higher the development level of a city, the more significant the effect of high-speed rail on its economic growth. Therefore, it is necessary to make full use of investment and subsidies to rationalize the planning of high-speed rail, in which a precise rational economic plan is needed [60]. Meanwhile, government should adopt appropriate employment guidance policies and talent incentive policies in less-developed areas and support small and micro-enterprises more to restrain the negative impact of losing high-quality factors in non-core cities.

In addition, the formation and improvement of the high-speed rail network can narrow the marginal gap of economic growth between different cities. In other words, although high-speed rail is still widening the gap between cities with diverse developing levels, the effect of high-speed rail networks in core and non-core cities has shown a convergence trend. By 2018, China has formed nine representative circle-like monocenter high-speed rail urban agglomerations. Such urban agglomerations have a diminishing capacity to obtain bonuses from the high-speed rail network from the core circle to the outskirts, reflecting the ability of resource sharing based on the connection of high-speed rail in a region. Thus, taking advantage of high-speed rail to create high-speed rail economic urban agglomerations and promote regional development is a reasonable way to realize economic convergence. Moreover, government should actively release policies to cultivate and graft new industries while retaining the original distinctive industries with comparative advantages to encourage the specialized division of labor within the high-speed rail urban agglomerations.

Finally, optimizing the spatial distribution pattern of hubs in the high-speed rail network is a pivotal procedure to drive regional growth with the agglomeration effect of high-speed rail and the radiation effect of the network. Currently, China’s high-speed rail city agglomerations and hub cities are mainly concentrated in the eastern region and the Yangtze River basin in the central region, while provinces such as Shanxi, Shaanxi, Gansu, and Ningxia in the middle and upper reaches of the Yellow River and Yunnan, Guizhou, and Sichuan in the southwest are more lacking. Consequently, future network planning should pay attention to increasing network density and foster high-speed rail hubs in these weak areas, thereby promoting regional economic growth and regional integration. Regions with relatively high levels of economy but low levels of centrality, such as Hunan Province and Sichuan Province, are faced with promising opportunities in high-speed rail planning. Those regions are in need of a higher density of high-speed rail networks and especially hub cities to act as growth poles to activate regional economic development. Thus, forthcoming studies should consider applying topology to analyze the network structure of high-speed rail and taking concepts such as structural holes and clustering coefficients into account to investigate weaknesses in the overall network, which would make it more precise to conduct the targeted arrangement of rail construction in the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.W. and W.L.; methodology, B.W. and W.L.; software, B.W.; validation, B.W., W.L. and J.C.; formal analysis, B.W.; investigation, B.W.; resources, J.C.; data curation, J.C.; writing—original draft preparation, B.W.; writing—review and editing, W.L.; visualization, B.W.; supervision, W.L.; project administration, W.L.; funding acquisition, B.W. and W.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2021YJS055), National Key Research and Development Program of China (2018YFB1201400), and National Social Science Foundation of China (17ZDA084).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available in the China City Statistical Yearbook and the official websites of the statistical bureaus in prefecture-level cities at http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Amos, P.; Bullock, D.; Sondhi, J. High-Speed Rail: The Fast Track to Economic Development? World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nash, C. When to Invest in High-Speed Rail Links and Networks? OECD/ITF Joint Transport Research Centre Discussion Paper: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, N.; Pels, E.; Nash, C. High-speed rail and air transport competition: Game engineering as tool for cost-benefit analysis. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2010, 44, 812–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Sun, T. The Siphon effects of transportation infrastructure on internal migration: Evidence from China’s HSR network. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2021, 28, 1066–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Mao, L.; Sun, C. Potential impacts of China 2030 high-speed rail network on ground transportation accessibility. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cao, J.; Liu, X.C.; Wang, Y.; Li, Q. Accessibility impacts of China’s high-speed rail network. J. Transp. Geogr. 2013, 28, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, S.-L.; Fang, Z.; Lu, S.; Tao, R. Impacts of high speed rail on railroad network accessibility in China. J. Transp. Geogr. 2014, 40, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-L. Reshaping Chinese space-economy through high-speed trains: Opportunities and challenges. J. Transp. Geogr. 2012, 22, 312–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmanan, T.R. The broader economic consequences of transport infrastructure investments. J. Transp. Geogr. 2011, 19, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pol, P.M. The Economic Impact of the High-Speed Train on Urban Regions. 2003. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/116148 (accessed on 30 August 2003).

- Farhadi, M. Transport infrastructure and long-run economic growth in OECD countries. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2015, 74, 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, N.; De Jong, M.; Storm, S.; Mi, J. Transport infrastructure, spatial clusters and regional economic growth in China. Transp. Rev. 2012, 32, 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plassard, F. High speed transport and regional development. In Regional policy, transport network; European Conference of Ministers of Transport: Paris, France, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Vickerman, R. Can high-speed rail have a transformative effect on the economy? Transp. Policy 2018, 62, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Diao, M. Does growth follow the rail? The potential impact of high-speed rail on the economic geography of China. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2018, 113, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.; Zhou, C.; Qin, C. No difference in effect of high-speed rail on regional economic growth based on match effect perspective? Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2017, 106, 144–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Y.; Wang, T.; Liang, S.; Yang, J.; Hou, P.; Qu, S.; Zhou, J.; Jia, X.; Wang, H.; Xu, M. Life cycle assessment of high speed rail in China. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2015, 41, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascetta, E.; Cartenì, A.; Henke, I.; Pagliara, F. Economic growth, transport accessibility and regional equity impacts of high-speed railways in Italy: Ten years ex post evaluation and future perspectives. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2020, 139, 412–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boopen, S. Transport infrastructure and economic growth: Evidence from Africa using dynamic panel estimates. Empir. Econ. Lett. 2006, 5, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Zhang, F.; Wang, F.; Ou, J. Regional economic growth and the role of high-speed rail in China. Appl. Econ. 2019, 51, 3465–3479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y. Spatial and temporal heterogeneity of the impact of high-speed railway on urban economy: Empirical study of Chinese cities. J. Transp. Geogr. 2021, 91, 102972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagler, Y.; Todorovich, P. Where High-Speed Rail Works Best. America 2050. 2009. Available online: http://www.america2050.org/2009/09/where-high-speed-rail-works-best.html (accessed on 1 September 2009).

- Jiao, J.; Wang, J.; Jin, F. Impacts of high-speed rail lines on the city network in China. J. Transp. Geogr. 2017, 60, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson, S.; Petiot, R. Can the high speed rail reinforce tourism attractiveness? The case of the high speed rail between Perpignan (France) and Barcelona (Spain). Technovation 2009, 29, 611–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetwitoo, J.; Kato, H. High-speed rail and regional economic productivity through agglomeration and network externality: A case study of inter-regional transportation in Japan. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2017, 5, 549–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracaglia, V.; D’Alfonso, T.; Nastasi, A.; Sheng, D.; Wan, Y.; Zhang, A. High-speed rail networks, capacity investments and social welfare. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2020, 132, 308–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coto-Millán, P.; Inglada, V.; Rey, B. Effects of network economies in high-speed rail: The Spanish case. Ann. Reg. Sci. 2007, 41, 911–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Sultana, S. The impacts of high-speed rail extensions on accessibility and spatial equity changes in South Korea from 2004 to 2018. J. Transp. Geogr. 2015, 45, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hong, J.; Chu, Z.; Wang, Q. Transport infrastructure and regional economic growth: Evidence from China. Transportation 2011, 38, 737–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Xue, J.; Rose, A.Z.; Haynes, K.E. The impact of high-speed rail investment on economic and environmental change in China: A dynamic CGE analysis. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2016, 92, 232–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deller, S.C. Economic Contributions of the Railroad Industry to Wisconsin: A Focus on the Publicly-Owned Railroad System in Southern Wisconsin; Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics, University of Wisconsin: Madison, WI, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison, G.; Glaeser, E.L.; Kerr, W.R. What causes industry agglomeration? Evidence from coagglomeration patterns. Am. Econ. Rev. 2010, 100, 1195–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cheng, S.; Lin, J.; Yang, D.; Liu, J.; Li, H. Carbon, water, land and material footprints of China’s high-speed railway construction. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2020, 82, 102314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ning, L.; Li, J.; Prevezer, M. Foreign direct investment spillovers and the geography of innovation in Chinese regions: The role of regional industrial specialization and diversity. Reg. Stud. 2016, 50, 805–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Yang, L.; Li, L. The implications of high-speed rail for Chinese cities: Connectivity and accessibility. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2018, 116, 308–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozbay, K.; Ozmen, D.; Berechman, J. Modeling and analysis of the link between accessibility and employment growth. J. Transp. Eng. 2006, 132, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Zhang, L.; Xin, Q. Transportation infrastructure and resource allocation of capital market: Evidence from high-speed rail opening and company going public. China J. Account. Stud. 2020, 8, 272–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Qin, Y.; Xie, Z. Does foreign technology transfer spur domestic innovation? Evidence from the high-speed rail sector in China. J. Comp. Econ. 2021, 49, 212–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinson, D.M. Accessibility impacts of high speed rail. J. Transp. Geogr. 2012, 22, 288–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hanson, G.H. Market potential, increasing returns and geographic concentration. J. Int. Econ. 2005, 67, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qin, Y. ‘No county left behind?’ The distributional impact of high-speed rail upgrades in China. J. Econ. Geogr. 2017, 17, 489–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, G.; Silva, J.d.A.e. Regional impacts of high-speed rail: A review of methods and models. Transp. Lett. 2013, 5, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wei, Y.D.; Li, Q.; Yuan, F. Economic transition and changing location of manufacturing industry in China: A study of the Yangtze River Delta. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ortega, E.; López, E.; Monzón, A. Territorial cohesion impacts of high-speed rail at different planning levels. J. Transp. Geogr. 2012, 24, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Z.; Diao, M.; Jing, K.; Li, W. High-speed rail and industrial movement: Evidence from China’s Greater Bay Area. Transp. Policy 2021, 112, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J. Social network analysis. Sociology 1988, 22, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrat, O. Social network analysis. In Knowledge Solutions; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 39–43. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, J. Social network analysis: Developments, advances, and prospects. Soc. Netw. Anal. Min. 2011, 1, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, L.C. Centrality in social networks conceptual clarification. Soc. Netw. 1978, 1, 215–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Freeman, L.C. A set of measures of centrality based on betweenness. Sociometry 1977, 40, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandes, U. A faster algorithm for betweenness centrality. J. Math. Sociol. 2001, 25, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurihara, T.; Wu, L. The impact of high speed rail on tourism development: A case study of Japan. Open Transp. J. 2016, 10, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Yang, Z.; Jiao, J.; Liu, W.; Wu, W. The effects of high-speed rail development on regional equity in China. Transp. Res. Part A: Policy Pract. 2020, 141, 180–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percoco, M. Highways, local economic structure and urban development. J. Econ. Geogr. 2016, 16, 1035–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, B.E. Threshold effects in non-dynamic panels: Estimation, testing, and inference. J. Econom. 1999, 93, 345–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, Q. Fixed-effect panel threshold model using Stata. Stata J. 2015, 15, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, Z. An Investigation on the Nonlinear Relationship between GovernmentSize, Expenditure Growth and Economic Growth. J. Quant. Tech. Econ. 2011, 28, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B. Economic Growth Effect of Industrial Restructuring and Productivity Improvement: Analysis of Dynamic Spatial Panel Model with Chinese City Data. China Ind. Econ. 2015, 12, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banister, D.; Berechman, Y. Transport investment and the promotion of economic growth. J. Transp. Geogr. 2001, 9, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rus, G.; Nombela, G. Is investment in high speed rail socially profitable? J. Transp. Econ. Policy (JTEP) 2007, 41, 3–23. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).