Application of the Constraint Negotiation Theory to the Plant-Based Meat Alternatives Food Service Business: An Exploration of Perceived Value and Negotiation–Constraint–Visit Intention Relationships

Abstract

:1. Introduction

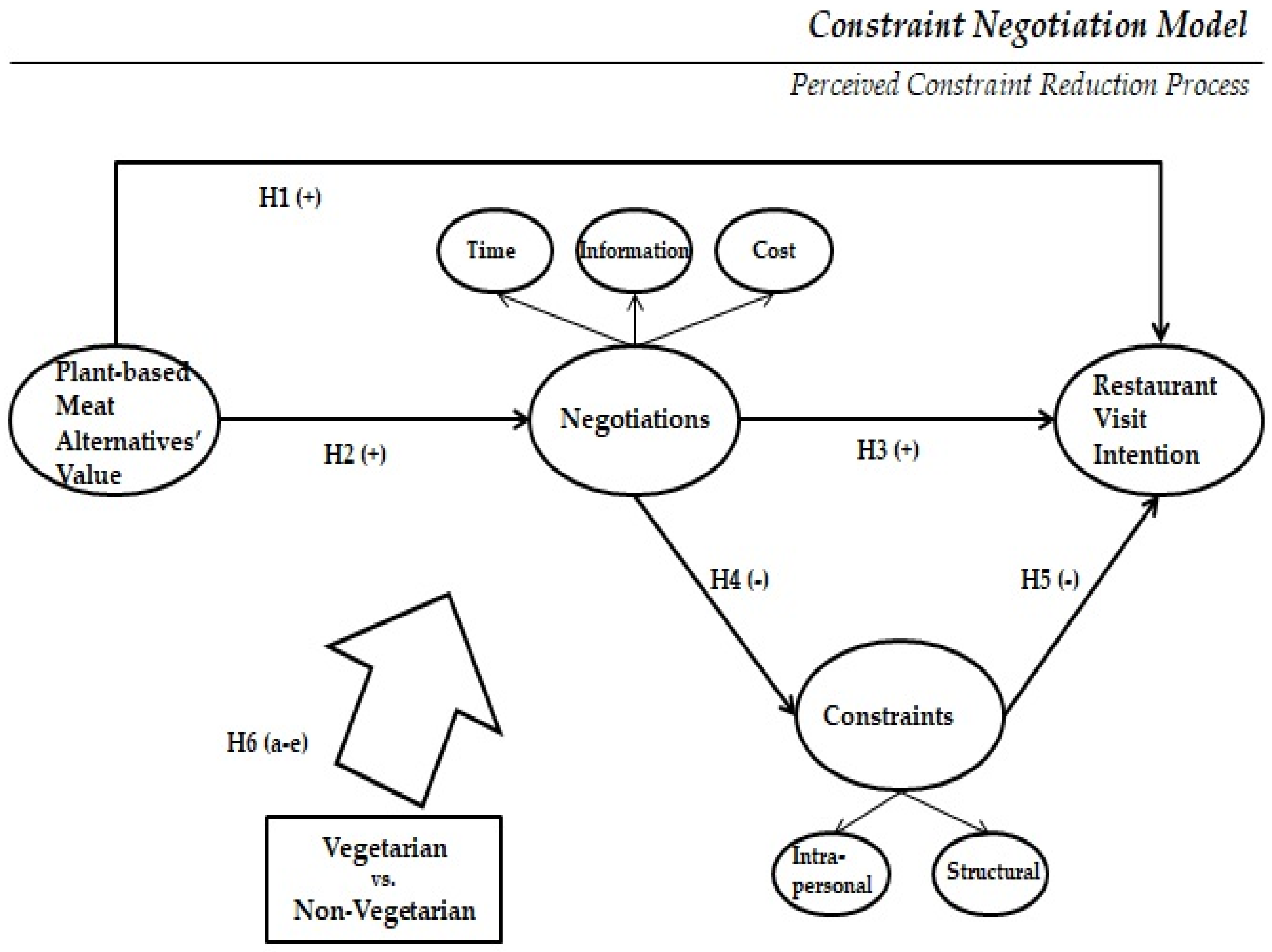

- To investigate the causal relationship between PBMAs’ value, restaurant visit intention, and negotiations (time, information acquisition, and cost).

- To analyze the causal relationship between negotiations, visit intention, and constraints (intrapersonal and structural). Additionally, the study examines the causal relationship between constraints and visit intention.

- To evaluate the moderating effect between vegetarians and non-vegetarians on all the aforementioned aspects.

2. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

2.1. Consumer Perceived Value of PBMAs

2.2. The Constraint Negotiation Theory

2.3. Relationships among the Constructs

2.3.1. Relationship between PBMAs’ Value and Restaurant Visit Intention

2.3.2. Relationship between PBMAs’ Value and Negotiations

2.3.3. Relationships between Consumers’ Negotiations and Restaurant Visit Intention

2.3.4. Relationship between Negotiations and Constraints

2.3.5. Relationship between Constraints and Restaurant Visit Intention

2.3.6. Moderating Role of Vegetarians vs. Non-Vegetarians

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection and Participants

3.2. Survey Instrument and Measures

- In the first step, the purpose of the study was explained to the participants, indicated that anonymity would be guaranteed, and informed consent was obtained online.

- In the second step, the concept of vegetarians was explained, and vegetarian participants were identified for the purpose of multigroup analysis.

- In the third step, general questions about all the constructs (e.g., PBMAs’ value, time, information, cost, intra-personal, structural factors, and restaurant visit intention) of this study were presented.

- Finally, six questions related to demographics were asked.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Sample Characteristics

4.2. Validity and Reliability of the Measurements

4.3. Results of Testing Hypotheses 1–5

4.4. Results of Testing Hypothesis 6

5. Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Managerial Implications

6. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bohrer, B.M. An investigation of the formulation and nutritional composition of modern meat analogue products. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness. 2019, 8, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phua, J.; Jin, S.V.; Kim, J. The roles of celebrity endorsers’ and consumers’ vegan identity in marketing communication about veganism. J. Mark. Commun. 2020, 26, 813–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Ge, J.; He, J.; Gan, R.; Fang, Y. Processing, quality, safety, and acceptance of meat analogue products. Engineering 2021, 7, 674–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreuders, F.K.G.; Schlangen, M.; Kyriakopoulou, K.; Boom, R.M.; van der Goot, A.J. Texture methods for evaluating meat and meat analogue structures: A review. Food Control 2021, 127, 108103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinrich, R. Opportunities for the adoption of health-based sustainable dietary patterns: A review on consumer research of meat substitutes. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhao, Y.; Yang, Q.E.; Zhou, X.; Wang, F.H.; Muurinen, J.; Virta, M.P.; Brandt, K.K.; Zhu, Y.G. Antibiotic resistome in the livestock and aquaculture industries: Status and solutions. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 51, 2159–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; He, X.; Feng, Y.; Wang, W.; Chen, H.; Gong, M.; Liu, D.; Clarke, J.L.; van Eerde, A. Pollution by antibiotics and antimicrobial resistance in LiveStock and poultry manure in China, and countermeasures. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohrmann, S.; Overvad, K.; Bueno-de-Mesquita, H.B.; Jakobsen, M.U.; Egeberg, R.; Tjønneland, A.; Nailler, L.; Boutron-Ruault, M.C.; Clavel-Chapelon, F.; Krogh, V.; et al. Meat consumption and mortality–results from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. BMC Med. 2013, 11, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, S.C.; Wolk, A. Meat consumption and risk of colorectal cancer: A meta-analysis of prospective studies. Int. J. Cancer. 2006, 119, 2657–2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Michel, F.; Hartmann, C.; Siegrist, M. Consumers’ associations, perceptions and acceptance of meat and plant-based meat alternatives. Food Qual. Preference 2021, 87, 104063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yook, S.J. Real Food the Domestic Meat Market Has Become Fierce. A War Aimed at the Characteristics of Koreans. Korea Herald News. Available online: http://mbiz.heraldcorp.com/view.php?ud=20220216000155 (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Morone, P.; Caferra, R.; D’Adamo, I.; Falcone, P.M.; Imbert, E.; Morone, A. Consumer willingness to pay for bio-based products: Do certifications matter? Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2021, 240, 108248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, I.; Keresztes, E.R. Perceived consumer effectiveness and willingness to pay for credence product attributes of sustainable foods. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, C.; Rhein, S.; Sträter, K.F. Consumers’ sustainability-related perception of and willingness-to-pay for food packaging alternatives. Resourc. Conserv. Recyc. 2022, 181, 106219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbard, J.; Mannell, R.C. Testing competing models of the leisure constraint negotiation process in a corporate employee recreation setting. Leis. Sci. 2001, 23, 145–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durmaz, Y.; Diyarbakırlıoğlu, I. A theoretical approach to the strength of motivation in customer behavior. Glob. J. Hum. Soc. Sci. 2011, 11, 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, L.L. Influencing Factors on Creative Tourists’ Revisiting Intentions: The Roles of Motivation, Experience and Perceived Value. Ph.D. Thesis, Clemson University, Clemson, SC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.; Koo, D.W. Visitors’ pro-environmental behavior and the underlying motivations for natural environment: Merging dual concern theory and attachment theory. J. Retailing Con. Serv. 2020, 56, 102147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, J.S.; Mowen, A.J.; Kerstetter, D.L. Testing alternative leisure constraint negotiation models: An extension of Hubbard and Mannell’s study. Leis. Sci. 2008, 30, 198–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.H. Targeting the Domestic Meat Substitute Market. New. Daily News. Available online: https://biz.newdaily.co.kr/site/data/html/2022/02/04/2022020400048.html (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Oh, J.M. Hong Jung-wook Ate and Sold 500,000 Units. Hankyung News. Available online: https://www.hankyung.com/economy/article/202202284863g (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Kang, J.E. Korean Food Companies Go Vegan to Target Meat-Alternative Market. The Korea Herald News. Available online: http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20211219000147 (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Kim, D.H. The Growing Meat Substitute Market. Newsis News. Available online: https://mobile.newsis.com/view.html?ar_id=NISX20220218_0001763912 (accessed on 7 March 2022).

- Fan, A.; Almanza, B.; Mattila, A.S.; Ge, L.; Her, E. Are vegetarian customers more “green”? J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2019, 22, 467–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakopoulou, K.; Dekkers, B.; van der Goot, A.J. Plant-based meat analogues. In Sustainable Meat Production and Processing; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 103–126. [Google Scholar]

- Zion Market Research. Global plant based meat market will reach USD21.23 billion by 2025. Available online: https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2019/03/28/1781303/0/en/Global-Plant-Based-Meat-Market-Will-Reach-USD-21-23-Billion-By-2025-Zion-Market-Research.html (accessed on 12 March 2022).

- Singh, M.; Trivedi, N.; Enamala, M.K.; Kuppam, C.; Parikh, P.; Nikolova, M.P.; Chavali, M. Plant-based meat analogue (PBMA) as a sustainable food: A concise review. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2021, 247, 2499–2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samard, S.; Ryu, G.H. A comparison of physicochemical characteristics, texture, and structure of meat analogue and meats. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 2708–2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuliarti, O.; Kiat Kovis, T.J.K.; Yi, N.J. Structuring the meat analogue by using plant-based derived composites. J. Food Eng. 2021, 288, 110138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagmann, D.; Siegrist, M.; Hartmann, C. Meat avoidance: Motives, alternative proteins and diet quality in a sample of Swiss consumers. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 2448–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Luciano, C.A.; de Aguiar, L.K.; Vriesekoop, F.; Urbano, B. Consumers’ willingness to purchase three alternatives to meat proteins in the United Kingdom, Spain, Brazil and the Dominican Republic. Food Qual. Preference 2019, 78, 103732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, D.W.; Godbey, G. Reconceptualizing barriers to family leisure. Leis. Sci. 1987, 9, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humagain, P.; Singleton, P.A. Exploring tourists’ motivations, constraints, and negotiations regarding outdoor recreation trips during COVID-19 through a focus group study. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tourism 2021, 36, 100447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roszkowska, E.; Kersten, G.E.; Wachowicz, T. The impact of negotiators’ motivation on the use of decision support tools in preparation for negotiations. Intl. Trans. Opt. Res. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kono, S.; Ito, E.; Loucks-Atkinson, A. The measurement model of leisure constraint negotiation in leisure-time physical activity context: Reflective or formative? J. Leis. Res. 2021, 52, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E.C.L.; Lai, M.Y.; Nimri, R. Do constraint negotiation and self-construal affect solo travel intention? The case of Australia. Int. J. Tourism Res. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, T.; Tang, J.; Wen, J.; Ye, S.; Zhou, Y.; Li, F. Traveling with pets: Constraints, negotiation, and learned helplessness. Tour. Manag. 2021, 82, 104183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Backman, K.F.; Chih Huang, Y. Creative tourism: A preliminary examination of creative tourists’ motivation, experience, perceived value and revisit intention. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2014, 8, 401–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhartanto, D.; Brien, A.; Primiana, I.; Wibisono, N.; Triyuni, N.N. Tourist loyalty in creative tourism: The role of experience quality, value, satisfaction, and motivation. Curr. Issues Tourism 2020, 23, 867–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Lee, C.K.; Kim, M.J.; Ryu, K. Restaurant healthy food quality, perceived value, and revisit intention: Testing a moderating role of green customers in South Korea. In International CHRIE Conference-Refereed Track; UMass Amherst: Denver, CO, USA, 2011; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Curvelo, I.C.G.; Watanabe, E. AdM.; Alfinito, S. Purchase intention of organic food under the influence of attributes, consumer trust and perceived value. Revesita Gestão 2019, 26, 198–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amelia, R.; Hidayatullah, S. The effect of Instagram engagement to purchase intention and consumers’ luxury value perception as the mediator in the skylounge restaurant. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Res. Technol. 2020, 5, 958–966. [Google Scholar]

- De Morais Watanabe, E.A.; Alfinito, S.; Curvelo, I.C.G.; Hamza, K.M. Perceived value, trust and purchase intention of organic food: A study with Brazilian consumers. Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 1070–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S.R.; Lee, S.W.; Jeon, H.M. The role of customer experience, food healthiness, and value for revisit intention in Grocerant. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Winter Falk, L.W.; Bisogni, C.A.; Sobal, J. Food choice processes of older adults: A qualitative investigation. J. Nutr. Educ. 1996, 28, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furst, T.; Connors, M.; Bisogni, C.A.; Sobal, J.; Falk, L.W. Food choice: A conceptual model of the process. Appetite 1996, 26, 247–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sualakamala, S.; Huffman, L. Value Negotiation for healthy food selection in restaurants. J. Culinary Sci. Technol. 2010, 8, 242–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, J.; Kyle, G.T. Understanding the role of identity in the constraint negotiation process. Leis. Sci. 2011, 33, 309–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, C.; Yoo, S.W.; Park, J.; Greenwell, T.C. Virtual reality and consumer behavior: Constraints, negotiation, negotiation-efficacy, and participation in virtual golf. Phys. Cult. Sport Stud. Res. 2020, 88, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.H.; Lee, M.J. Relationships between leisure constraint negotiation strategy and leisure constraint based on types of leisure sport: Focus on leisure constraint reduction theory. Leis. Stud. 2013, 11, 83–100. [Google Scholar]

- Das, A.K.; Nanda, P.K.; Dandapat, P.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; Gullón, P.; Sivaraman, G.K.; McClements, D.J.; Gullón, B.; Lorenzo, J.M. Edible mushrooms as functional ingredients for development of healthier and more sustainable muscle foods: A flexitarian approach. Molecules 2021, 26, 2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabès, A.; Seconda, L.; Langevin, B.; Allès, B.; Touvier, M.; Hercberg, S.; Lairon, D.; Baudry, J.; Pointereau, P.; Kesse-Guyot, E. Greenhouse gas emissions, energy demand and land use associated with omnivorous, pesco-vegetarian, vegetarian, and vegan diets accounting for farming practices. Sustain. Prod. Consump. 2020, 22, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Povey, R.; Wellens, B.; Conner, M. Attitudes towards following meat, vegetarian and vegan diets: An examination of the role of ambivalence. Appetite 2001, 37, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Phua, J.; Jin, S.V.; Kim, J. Pro-veganism on Instagram: Effects of user-generated content (UGC) types and content generator types in Instagram-based health marketing communication about veganism. Online Inf. Rev. 2020, 44, 685–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lea, E.; Worsley, T. Australians’ organic food beliefs, demographics and values. Br. Food J. 2005, 107, 855–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Han, J.-S.; Yang, D.-H. Effects of consumption experience on customer satisfaction and customer happiness for dessert cafe. Culin. Sci. Hosp. Res. 2017, 23, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R. Multivariate Data Analysis; Cengage: Boston, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.K. Tourism Research and Statistical Analysis; Daewangsa: Seoul, Korea, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- D’Adamo, I.; Falcone, P.M.; Martin, M.; Rosa, P. A sustainable revolution: Let’s go sustainable to get our globe cleaner. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManners, P.J. Adapt and Thrive: The Sustainable Revolution; Susta Press: London, UK, 2008; ISBN 0955736900. [Google Scholar]

- Birchal, R.A.M.d.C.; Moura, L.R.C.; Vasconcelos, F.C.W.; da Silveira Cunha, N.R. The value perceived and the sacrifice perceived by vegetarian food consumers. Rev. Pensamento Contemp. Admin. 2018, 12, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, Y.N.; Jang, H.J.; Choi, Y.W.; Choi, Y.S.; Oh, J.E. A study on the consumer perception and importance-performance analysis of the vegetarian meal-kit development. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2021, 21, 324–335. [Google Scholar]

- Salehi, G.; Díaz, E.M.; Redondo, R. Consumers’ switching to vegan, vegetarian, and plant-based (veg* an) diets: A systematic review of literature. In Proceedings of the 19th International Congress on Public and Nonprofit Marketing Sustainability: New Challenges for Marketing and Socioeconomic Development, Online, 2–4 July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.; Bai, J. The role of public participation in environmental governance: Empirical evidence from China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Characteristics | n (%) | Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | Monthly income | ||

| 18–19 | 0 (0) | ≤$1000 | 30 (9.5) |

| 20–29 | 80 (25.4) | $1001–$2000 | 38 (12.1) |

| 30–39 | 99 (31.4) | $2001–$3000 | 101 (32.1) |

| 40–49 | 94 (29.8) | $3001–$4000 | 52 (16.5) |

| 50–59 | 33 (10.5) | $4001–$5000 | 44 (14) |

| 60 or older | 9 (2.9) | >$5000 | 50 (15.9) |

| Gender | Occupation | ||

| Men | 155 (49.2) | Student | 35 (11.1) |

| Women | 160 (50.8) | Office job | 144 (45.7) |

| Marital status | Self-employed | 21 (6.7) | |

| Unmarried | 162 (51.4) | Professional job | 59 (18.7) |

| Married | 150 (47.6) | Homemaker | 31 (9.8) |

| Other | 3 (1) | Other | 25 (7.9) |

| Educational level | |||

| High school | 41 (13) | ||

| Two-year college | 52 (16.5) | ||

| University | 184 (58.4) | ||

| Graduate school | 38 (12.1) |

| Construct | Standardized Loadings | t-Value | CCR a | AVE b | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBMAs’ value | 0.878 | 0.644 | 0.882 | ||

| PBMAs are healthier than real meat | 0.863 | Fixed | |||

| PBMAs are better for animal welfare than real meat | 0.786 | 17.130 *** | |||

| PBMAs are better for the environment than real meat | 0.804 | 17.819 *** | |||

| PBMAs have more nutritional benefits than real meat | 0.753 | 15.983 *** | |||

| Time | 0.862 | 0.611 | 0.873 | ||

| I’m willing to invest my time to choose between PBMAs | 0.744 | Fixed | |||

| I’m going to switch to PBMAs soon | 0.769 | 19.342 *** | |||

| I can devote my time to PBMA consumption | 0.74 | 13.338 *** | |||

| I can invest sufficient time for PBMA consumption | 0.867 | 15.881 *** | |||

| Information acquisition | 0.889 | 0.666 | 0.892 | ||

| I tend to learn new information about PBMAs | 0.800 | Fixed | |||

| I’m interested in PBMA-related information | 0.809 | 15.947 *** | |||

| I tend to constantly acquire PBMA-related information | 0.796 | 15.657 *** | |||

| If it helps others, I’m willing to share PBMA-related information with people | 0.859 | 17.267 *** | |||

| Cost | 0.796 | 0.566 | 0.794 | ||

| I’m thinking of spending more of my money on PBMA consumption | 0.764 | Fixed | |||

| I’m willing to pay for PBMA consumption | 0.71 | 12.378 *** | |||

| I plan to consume PBMAs within my budget | 0.781 | 13.705 *** | |||

| Intrapersonal | 0.854 | 0.662 | 0.850 | ||

| I am not that interested in PBMAs | 0.766 | Fixed | |||

| I can’t afford to eat PBMA | 0.874 | 14.972 *** | |||

| I don’t like PBMAs | 0.797 | 14.025 *** | |||

| Structural | 0.835 | 0.630 | 0.832 | ||

| I don’t have enough time to look for any restaurants specializing in PBMAs | 0.721 | Fixed | |||

| I’m too busy to look for any restaurants specializing in PBMAs | 0.872 | 13.596 *** | |||

| I don’t have the right information about PBMAs | 0.78 | 12.702 *** | |||

| Restaurant visit intention | 0.924 | 0.754 | 0.924 | ||

| I’m willing to visit a restaurant that serves PBMAs | 0.898 | Fixed | |||

| I’m willing to visit a restaurant that specializes in PBMAs | 0.886 | 23.289 *** | |||

| I want to visit a restaurant that serves PBMAs | 0.798 | 18.851 *** | |||

| I will visit more restaurants that serve PBMAs in the future | 0.887 | 23.339 *** |

| Construct | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | Mean | SD a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. PBMAs’ value | 0.802 | 3.422 | 0.800 | ||||||

| 2. Time | 0.796 | 0.781 | 3.178 | 0.819 | |||||

| 3. Information acquisition | 0.694 | 0.806 | 0.816 | 3.004 | 0.870 | ||||

| 4. Cost | 0.719 | 0.666 | 0.672 | 0.752 | 3.383 | 0.794 | |||

| 5. Intrapersonal | −0.351 | −0.247 | −0.229 | −0.362 | 0.813 | 2.174 | 0.715 | ||

| 6. Structural | −0.418 | −0.387 | −0.376 | −0.434 | 0.585 | 0.793 | 2.300 | 0.711 | |

| 7. Visit Intention | 0.766 | 0.710 | 0.614 | 0.651 | −0.346 | −0.411 | 0.868 | 3.338 | 0.881 |

| Relationships | β | B | S.E. | t-Value | p-Value | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Value → Visit intention | 0.375 | 0.389 | 0.145 | 2.685 ** | 0.007 | Supported |

| H2 | Value → Negotiations | 0.934 | 0.776 | 0.054 | 14.241 *** | 0.000 | Supported |

| H3 | Negotiations → Visit intention | 0.400 | 0.500 | 0.184 | 2.714 ** | 0.007 | Supported |

| H4 | Negotiations → Constraints | −0.524 | −0.344 | 0.059 | −5.845 *** | 0.000 | Supported |

| H5 | Constraints → Visit intention | −0.089 | −0.170 | 0.081 | −2.093 * | 0.036 | Supported |

| Structural Relationship | Vegetarians (n = 155) | Non-Vegetarians (n = 160) | Free | Constrained | △χ2 | Results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t-Value | t-Value | χ2(df = 512) | χ2(df = 513) | |||||

| H6a. V → VI | 0.352 | 1.943 | 0.175 | 0.717 | 999.691 | 999.945 | 0.254 | Not Supported |

| H6b. V → N | 0.899 | 7.756 *** | 0.943 | 9.320 *** | 999.691 | 1004.754 | 5.063 | Supported |

| H6c. N → VI | 0.300 | 1.486 | 0.608 | 2.333 * | 999.691 | 1001.901 | 2.21 | Not Supported |

| H6d. N → C | −0.670 | −5.457 *** | −0.385 | −2.544 * | 999.691 | 1004.495 | 4.804 | Supported |

| H6e. C → VI | −0.246 | −2.679 ** | −0.029 | −0.588 | 999.691 | 1001.275 | 1.584 | Not Supported |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jang, H.-W.; Cho, M. Application of the Constraint Negotiation Theory to the Plant-Based Meat Alternatives Food Service Business: An Exploration of Perceived Value and Negotiation–Constraint–Visit Intention Relationships. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5812. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14105812

Jang H-W, Cho M. Application of the Constraint Negotiation Theory to the Plant-Based Meat Alternatives Food Service Business: An Exploration of Perceived Value and Negotiation–Constraint–Visit Intention Relationships. Sustainability. 2022; 14(10):5812. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14105812

Chicago/Turabian StyleJang, Ha-Won, and Meehee Cho. 2022. "Application of the Constraint Negotiation Theory to the Plant-Based Meat Alternatives Food Service Business: An Exploration of Perceived Value and Negotiation–Constraint–Visit Intention Relationships" Sustainability 14, no. 10: 5812. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14105812

APA StyleJang, H.-W., & Cho, M. (2022). Application of the Constraint Negotiation Theory to the Plant-Based Meat Alternatives Food Service Business: An Exploration of Perceived Value and Negotiation–Constraint–Visit Intention Relationships. Sustainability, 14(10), 5812. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14105812