Revealing Consumer Behavior toward Green Consumption

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Green Products

- ▪ Should not be dangerous to the health of people and animals;

- ▪ Should not harm the environment during its production, use and disposal;

- ▪ Should not consume a disproportionate amount of energy and resources during its production, use and disposal;

- ▪ Should not cause waste due to excessive packaging.

- Provide an opportunity to reduce global environmental problems;

- Energy saving;

- Do not create pollution;

- Ease of repair;

- Designed to be reused or recycled;

- Produced with minimal packaging;

- Produced from renewable resources;

- Based on the security principle;

- Produced from local sources to reduce distribution costs;

- Designed to meet genuine and sincere human needs;

- Provide sufficient information on the label;

- Harmless to human health;

- Do not contain harmful substances;

- Not tested on animals.

2.2. Green Consumers

- Active green consumers whose purchasing behavior is largely shaped by environmental concerns;

- Passive green consumers whose purchasing behavior is partly shaped by environmental concerns.

2.3. Green Consumption Behavior

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Technique and Questions

- ✓ I prefer reusable products to disposable ones.

- ✓ I prefer to buy the same product in a larger package.

- ✓ I use the product until it is completely worn out.

- ✓ I buy used goods to reduce unnecessary consumption.

- ✓ I separate waste, such as paper, glass, plastic bottles, batteries, etc.

- ✓ I want to receive documents by e-mail so as not to use extra paper.

- ✓ Instead of buying products that I will use temporarily, I borrow them from my relatives and friends.

- ✓ I don’t use a plastic bag and put groceries in my bag when I’m shopping.

- ✓ I donate unused clothes to those who need them.

- ✓ I prefer to buy products that blend quickly with nature.

- ✓ I buy packaged products made from recycled papers.

- ✓ I buy products made from environmentally friendly materials.

- ✓ I pay attention to the type of energy I use so as not to increase air pollution.

- ✓ Although expensive, I buy lamps that consume less electricity.

- ✓ I buy energy-saving electrical appliances.

- ✓ When the weather gets colder, I prefer to wear warm clothes rather than raise the temperature.

- ✓ I turn off unnecessary lights.

- ✓ While brushing my teeth, washing dishes, etc., I turn off the faucet.

- “What characteristics do survey participants attribute to environmental products?”

- “What factors do survey participants pay attention to when consuming?”

- “What are the main characteristics of the ecological consumer behavior of the survey participants?”

3.2. Research Scope

4. Data Analysis and Findings

4.1. General Characteristics of Survey Participants

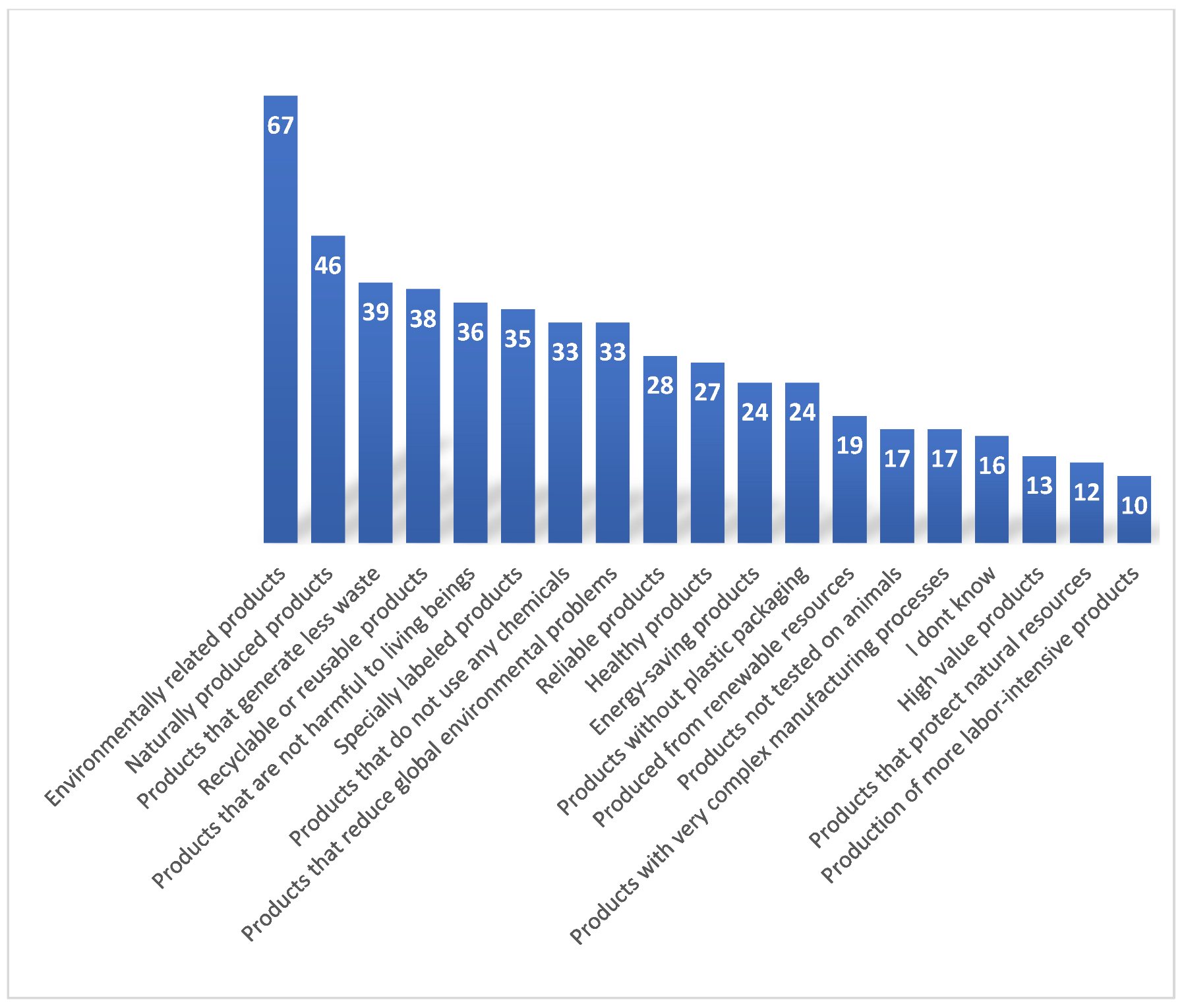

4.2. Results for Survey Participants’ Statements on Definition of Green Products

4.3. Results for Indicators That Consumers Paid Attention To

4.4. Data Analysis and Results for Items Oriented toward Measuring Environmental Consumer Behavior

- -

- “I donate unused clothes to those who need them.” (0.725 and 0.748);

- -

- “I don’t use a plastic bag and put groceries in my bag when I’m shopping.” (0.580 and 0.593);

- -

- “I use the product until it is completely worn out.” (0.715 and 0.791);

- -

- “Although expensive, I buy lamps that consume less electricity.” (0.814 and 0.863).

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Number | Percent (%) | Number | Percent (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Marital Status | ||||

| Male | 253 | 47.2 | Married | 217 | 40.5 |

| Female | 283 | 52.8 | Single | 319 | 59.5 |

| Education Level | Number of Household Members | ||||

| High school | 58 | 10.8 | Up to 2 people | 119 | 22.2 |

| Bachelor’s | 348 | 64.9 | 3 or 4 people | 185 | 34.5 |

| Master’s | 98 | 18.3 | 5 or 6 people | 143 | 26.7 |

| Ph.D | 32 | 6 | More than 6 people | 89 | 16.6 |

| Monthly Income | Shopping Frequency | ||||

| Up to 300 manats | 123 | 22.9 | Every day | 160 | 29.9 |

| Between 300–600 manats | 199 | 37.1 | 2–3 times a week | 133 | 24.8 |

| Between 601–1000 manats | 89 | 16.6 | Once a week | 94 | 17.5 |

| Between 1001–1500 manats | 98 | 18.3 | 2–3 times a month | 71 | 13.2 |

| More than 1500 manats | 27 | 5.04 | Once a month | 78 | 14.6 |

| Age | |||||

| 18–29 years | 189 | 35.3 | |||

| 30–45 years | 155 | 28.9 | |||

| 46–64 years | 94 | 17.5 | |||

| 65 years and over | 98 | 18.3 | |||

| N = 535 | |||||

Appendix B

| Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy | 0.813 | |

|---|---|---|

| Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity | Approx. Chi-Square | 10,216.520 |

| Df | 351 | |

| Sig. | <0.001 | |

Appendix C

| Pattern Matrix a | Cronbach’s Alpha Based on Standardized Items | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Production and expiration date | −0.709 | |||

| Being eco-friendly | −0.690 | |||

| Freshness | −0.612 | 0.504 | ||

| Ingredients | −0.402 | |||

| Brand | 0.843 | 0.849 | ||

| Expert opinions | 0.832 | |||

| Appearance | 0.755 | |||

| Price | 0.762 | 0.813 | ||

| Label information | 0.624 | |||

| Advertising | 0.891 | |||

Appendix D

| Component 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Box’s Test Sig. | Pillai’s Trace Sig. | Wilks’ Lambda Sig. | Levene’s Test (Based on Mean) | |||

| Brand | Expert Opinions | Appearance | ||||

| Gender | 0.001 | 0.067 | 0.000 | 0.816 | 0.532 | 0.970 |

| Marital status | 0.005 | 0.053 | 0.548 | 0.589 | 0.742 | 0.604 |

| Education level | 0.030 | 0.096 | 0.513 | 0.232 | 0.789 | 0.563 |

| Income | 0.683 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.871 | 0.425 | 0.386 |

| Number of household members | 0.542 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.140 | 0.158 | 0.013 |

| Shopping frequency | 0.025 | 0.083 | 0.263 | 0.708 | 0.391 | 0.663 |

| Age | 0.014 | 0.057 | 0.384 | 0.047 | 0.104 | 0.393 |

| Component 3 | ||||||

| Box’s Test Sig. | Pillai’s Trace Sig. | Wilks’ Lambda Sig. | Levene’s Test (Based on Mean) | |||

| Price | Label Information | Advertising | ||||

| Gender | 0.003 | 0.084 | 0.156 | 0.003 | 0.089 | 0.367 |

| Marital Status | 0.001 | 0.091 | 0.329 | 0.360 | 0.419 | 0.224 |

| Education level | 0.136 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.037 | 0.270 | 0.163 |

| Income | 0.762 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.896 | 0.733 | 0.382 |

| Number of household members | 0.294 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.452 | 0.046 | 0.012 |

| Shopping frequency | 0.000 | 0.065 | 0.352 | 0.031 | 0.014 | 0.524 |

| Age | 0.000 | 0.043 | 0.572 | 0.429 | 0.603 | 0.187 |

Appendix E

| Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy | 0.805 | |

|---|---|---|

| Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity | Approx. Chi-Square | 11,317.065 |

| Df | 453 | |

| Sig. | <0.001 | |

Appendix F

| Pattern Matrix a | Cronbach’s Alpha Based on Standardized Items | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component | |||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| Instead of buying products that I will use temporarily, I borrow them from my relatives and friends. | 0.679 | ||||

| I prefer to buy the same product in a larger package. | 0.594 | ||||

| I want to receive documents by e-mail so as not to use extra paper. | 0.707 | 0.835 | |||

| I buy packaged products made from recycled paper. | −0.853 | ||||

| I buy products made from environmentally friendly materials. | −0.573 | ||||

| I prefer to buy products that blend quickly with nature. | −0.680 | ||||

| When the weather gets colder, I prefer to wear warm clothes rather than raise the temperature. | −0.827 | 0.449 | |||

| I prefer reusable products to disposable ones. | 0.747 | ||||

| I turn off unnecessary lights. | −0.658 | ||||

| I buy energy-saving electrical appliances. | −0.635 | ||||

| While brushing my teeth, washing dishes, etc., I turn off the faucet. | −0.623 | 0.769 | |||

| I pay attention to the type of energy I use so as not to increase air pollution. | 0.745 | ||||

| I buy used goods to reduce unnecessary consumption. | 0.648 | ||||

| I separate waste such as paper, glass, plastic bottles, batteries, etc. | 0.405 | 0.803 | |||

Appendix G

| Component 1 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Box’s Test Sig. | Pillai’s Trace Sig. | Wilks’ Lambda Sig. | Levene’s Test (Based on Mean) | ||||||||

| Instead of buying products that I will use temporarily, I borrow them from my relatives and friends. | I prefer to buy the same product in a larger package. | I want to receive documents by e-mail so as not to use extra paper. | |||||||||

| Gender | 0.020 | 0.035 | 0.305 | 0.325 | 0.783 | 0.453 | |||||

| Marital status | 0.001 | 0.087 | 0.276 | 0.275 | 0.301 | 0.705 | |||||

| Education level | 0.000 | 0.029 | 0.330 | 0.137 | 0.436 | 0.273 | |||||

| Income | 0.351 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.482 | 0.120 | 0.032 | |||||

| Number of household members | 0.016 | 0.001 | 0.0049 | 0.307 | 0.644 | 0.258 | |||||

| Shopping frequency | 0.003 | 0.169 | 0.204 | 0.568 | 0.432 | 0.345 | |||||

| Age | 0.487 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.008 | 0.638 | 0.597 | |||||

| Component 3 | |||||||||||

| Box’s Test Sig. | Pillai’s Trace Sig. | Wilks’ Lambda Sig. | Levene’s Test (Based on Mean) | ||||||||

| I prefer reusable products to disposable ones. | I turn off unnecessary lights. | I buy energy-saving electrical appliances. | While brushing my teeth, washing dishes, etc., I turn off the faucet. | ||||||||

| Gender | 0.001 | 0.029 | 0.000 | 0.240 | 0.373 | 0.544 | 0.743 | ||||

| Marital status | 0.243 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.358 | 0.011 | 0.493 | 0.022 | ||||

| Education level | 0.002 | 0.004 | 0.000 | 0.518 | 0.407 | 0.190 | 0.673 | ||||

| Income | 0.825 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.792 | 0.435 | 0.044 | 0.763 | ||||

| Number of household members | 0.810 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.027 | 0.042 | 0.693 | 0.521 | ||||

| Shopping frequency | 0.000 | 0.010 | 0.761 | 0.264 | 0.534 | 0.324 | 0.753 | ||||

| Age | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.007 | 0.621 | 0.614 | 0.021 | 0.279 | ||||

| Component 4 | |||||||||||

| Box’s Test Sig. | Pillai’s Trace Sig. | Wilks’ Lambda Sig. | Levene’s Test (Based on Mean) | ||||||||

| I pay attention to the type of energy I use so as not to increase air pollution. | I buy used goods to reduce unnecessary consumption. | I separate waste such as paper, glass, plastic bottles, batteries, etc. | |||||||||

| Gender | 0.020 | 0.060 | 0.000 | 0.091 | 0.543 | 0.274 | |||||

| Marital status | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.282 | 0.365 | 0.327 | |||||

| Education level | 0.000 | 0.038 | 0.000 | 0.438 | 0.439 | 0.193 | |||||

| Income | 0.404 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.228 | 0.471 | 0.221 | |||||

| Number of household members | 0.010 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.536 | 0.126 | 0.437 | |||||

| Shopping frequency | 0.028 | 0.074 | 0.071 | 0.197 | 0.098 | 0.490 | |||||

| Age | 0.653 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.472 | 0.019 | 0.024 | |||||

References

- Sharma, B.R.; Sharma, D. Impact of Climate Change on Water Resources and Glacier Melt and Potential Adaptations for Indian Agriculture. In Proceedings of the 33rd Indian Agricultural Universities Association Vice Chancellors Annual Convention on “Climate Change and its Effect on Agriculture”, Anand Agricultural University, Anand, India, 4–5 December 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mammadli, M.; Sadik-Zada, E.R.; Gatto, A.; Huseynova, R. What Drives Public Debt Growth? A Focus on Natural Resources, Sustainability and Development. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy Econj. 2021, 11, 614–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelrod, L.J.; Lehman, D.R. Responding to environmental concerns: What factors guide individual action? J. Environ. Psychol. 1993, 13, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt, J.; Solomon, S.; Kasser, T.; Sheldon, K.M. The urge to splurge: A terror management account of materialism and consumer behavior. J. Consum. Psychol. 2004, 14, 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Proposal for a Council Decision on the Conclusion on Behalf of the European Union of the Paris Agreement Adopted under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Publications Office of the EU; Document 52016PC0395; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Almond, R.E.A.; Grooten, M.; Petersen, T. Living Planet Report 2020—Bending the Curve of Biodiversity Loss; World Wildlife Fund (WWF): Gland, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division 2019. World Population Prospects 2019: Highlights; ST/ESA/SER.A/423; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zinkhan, G.M.; Carlson, L. Green advertising and the reluctant consumer. J. Advert. 1995, 24, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simãoab, L.; Lisboa, A. Green marketing and green brand—The toyota case. Procedia Manuf. 2017, 12, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnear, T.C.; Taylor, J.R.; Ahmed, S.A. Ecologically Concerned Consumers: Who Are They? J. Mark. 1974, 38, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sesini, G.; Castiglioni, C.; Lozza, E. New Trends and Patterns in Sustainable Consumption: A Systematic Review and Research Agenda. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMeekin, A.; Southerton, D. Sustainability transitions and final consumption: Practices and socio-technical systems. Technol. Anal. Strateg. 2012, 24, 345–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.L. Beyond greening: Strategies for a sustainable world. Harward Bus. Rev. 1997, 75, 66–76. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, X.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Corporate Social Responsibility, Customer Satisfaction, and Market Value. J. Mark. 2006, 70, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baziana, S.; Tzimitra-Kalogianni, E. Investigation of consumer behavior: A study on organic wine. Int. J. Soc. Ecol. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 7, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Peattie, K. Environmental Marketing Management: Meeting the Green Challenge; Pitman: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Sadik-Zada, E.R.; Gatto, A.; Blick, N. Rural Electrification and Transition to Clean Cooking: The Case Study of Kanyegaramire and Kyamugarura Solar Mini-Grid Energy Cooperatives in the Kyenjojo District of Uganda, In Sustainable Policies and Practices in Energy, Environment and Health Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zelezny, L.C.; Schultz, P.W. Promoting environmentalism. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeynalova, Z.; Mammadli, M. Analysis of the economic factors affecting household consumption expenditures in Azerbaijan. J. Crit. Rev. 2020, 7, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fróna, D.; Szenderák, J.; Harangi-Rákos, M. The Challenge of Feeding the World. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeir, I.; Weijters, B.; de Houwer, J.; Geuens, M.; Slabbinck, H.; Spruyt, A.; van Kerckhove, A.; van Lippevelde, W.; de Steur, H.; Verbeke, W. Environmentally Sustainable Food Consumption: A Review and Research Agenda from a Goal-Directed Perspective. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorek, S.; Spangenberg, J.H. Sustainable consumption within a sustainable economy—Beyond green growth and green economies. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 63, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verain, M.C.; Dagevos, H.; Antonides, G. Sustainable food consumption. Product choice or curtailment? Appetite 2015, 91, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.; Luomala, H. A Comparison of Motivational Patterns in Sustainable Food Consumption between Pakistan and Finland: Duties or SelfReliance? J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2021, 33, 459–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Hall, C.M.; Kim, D.-K. Predicting environmentally friendly eating out behavior by value-attitude-behavior theory: Does being vegetarian reduce food waste? J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 28, 797–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Sustainable Development in the European Union, Monitoring Report on Progress towards the SDGs in an EU Context; Eurostat: Luxembourg, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Reflection Paper towards a Sustainable Europe by 2030; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H.; Yu, J.; Kim, H.C.; Kim, W. Impact of social/personal norms and willingness to sacrifice on young vacationers’ pro-environmental intentions for waste reduction and recycling. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 2117–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Global Initiative on Food Loss and Waste Reduction; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2015; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Mesterházy, A.; Oláh, J.; Popp, J. Losses in the Grain Supply Chain: Causes and Solutions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wu, X.; Guo, H.; Zheng, X.; Mai, B. Pollution of plastic debris and halogenated flame retardants (HFRs) in soil from an abandoned e-waste recycling site: Do plastics contribute to (HFRs) in soil? J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 410, 124649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Confente, I.; Scarpi, D.; Russo, I. Marketing a new generation of bio-plastics products for a circular economy: The role of green self-identity, self-congruity, and perceived value. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 112, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matuszewska, A.; Ha´nderek, A.; Paczuski, M.; Biernat, K. Hydrocarbon Fractions from Thermolysis of Waste Plastics as Components of Engine Fuels. Energies 2021, 14, 7245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matuszewska, A.; Owczuk, M.; Biernat, K. Current Trends in Waste Plastics’ Liquefaction into Fuel Fraction: A Review. Energies 2022, 15, 2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazdecki, M.; Gorynska-Goldmann, E.; Kiss, M.; Szakály, Z. Segmentation of Food Consumers Based on Their Sustainable Attitude. Energies 2021, 14, 3179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeynalova, Z. The Effect of Tax Revenues on Economic Growth in Azerbaijan. J. Crit. Rev. 2020, 7, 166–172. [Google Scholar]

- Zeynalova, Z. The applying functions of tax regulation for state development. Aust. Econ. Pap. 2020, 59, 376–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrum, L.J.; McCarty, J.A.; Lowrey, T.M. Buyer Characteristics of the Green Consumer and Their Implications for Advertising Strategy. J. Advert. 1995, 14, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadik-Zada, E.R. Political Economy of Green Hydrogen Rollout: A Global Perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, R.Y. Determinants of Chinese consumers’ green purchase behavior. Psychol. Mark. 2001, 4, 389–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen, P.S.; Wiener, J.L.; Cobb-Walgren, C. The role of perceived consumer effectiveness in motivating environmentally conscious behaviors. J. Public Policy Mark. 1991, 10, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minton, A.P.; Rose, R.L. The effects of environmental concern on environmentally friendly consumer behavior: An exploratory study. J. Bus. Res. 1997, 40, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, D.C.; Nique, W.M.; Anna, E.; Herter, M.M. Green consumer values: How do personal values influence environmentally responsible water consumption? Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2011, 35, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.A.; Bacon, D.R. Explaning the Subtle Relationship Between Environmental Concern and Ecologically Conscious Consumer Behaviour. J. Bus. Res. 1997, 40, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.B.; Chai, L.T. Attitude Towards the Environment and Green Products: Consumers’ Perspective. Manag. Sci. Eng. 2010, 4, 27–39. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.; Choi, S.M. Antecedents of Green Purchase Behavior: An Examination of Collectivism, Environmental Concern, and PCE. Adv. Consum. Res. 2005, 32, 592–599. [Google Scholar]

- Ottman, J.A.; Stafford, E.R.; Hartman, C.L. Avoiding green marketing myopia: Ways to improve consumer appeal for environmentally preferable products environment. Sci. Policy Sustain. Dev. 2006, 48, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlegelmilch, B.B.; Bohlen, G.M.; Diamantopoulos, A. The link between gren purchasing decisions and measures of environmental consciousness. Eur. J. Mark. 1996, 30, 35–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamdasani, P.; Chon-Lin, G.O.; Richmond, D. Exploring Green Consumers in an Oriental Culture: Role of Personal and Marketing Mix Factors. Adv. Consum. Res. 1993, 20, 488–493. [Google Scholar]

- Sütterlin, B.; Brunner, T.A.; Siegrist, M. Who puts the most energy into energy conservation? A segmentation of energy consumers based on energy-related behavioral characteristics. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 8137–8152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moisander, J. Motivational Complexity of Green Consumerism. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2007, 31, 404–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, I. Greener Marketing: A Responsible Approach to Business; Charter, M., Ed.; Greenleaf Publishing: Sheffield, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Thøgersen, J. Spillover processes in the development of a sustainable consumption pattern. J. Econ. Psychol. 1999, 20, 53–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trudel, R. Sustainable consumer behavior. Consum. Psychol. Rev. 2019, 2, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Khan, A.A.; Ahmed, I. Determinants of Pakistani consumers’ green purchase behavior: Some insights from a developing country. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2011, 2, 217–226. [Google Scholar]

- Ishaswini, N.; Datta, S.K. Pro-environmental concern influencing green buying: A study on Indian consumers. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2011, 6, 124–133. [Google Scholar]

- Ölander, F.; Thøgersen, J. Understanding of consumer behaviour as a prerequisite for environmental protection. J. Consum. Policy 1995, 18, 345–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Polonsky, M.J. An analysis of the green consumer domain within sustainability research: 1975 to 2014. Australas. Mark. J. 2017, 25, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangsa, A.B.; Schlegelmilch, B.B. Linking sustainable product attributes and consumer decision-making: Insights from a systematic review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 245, 118902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dursun, İ.; Kabadayı, E.; Tuğer, A. Pro-Environmental Consumption Behavior: Dimensions and Measurement. Acad. Rev. Econ. Adm. Sci. 2018, 11, 42–66. [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi, M.; Sen, K. Environmentally responsive consumption: A study of young consumers in Indıa. Int. J. Multidiscip. Thought 2013, 3, 439–447. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, J.A. Green consumers in the 1990s: Profile and implications for advertising. J. Bus. Res. 1996, 36, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J. Sustainable consumption in China: New trends and research interests. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 1507–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Sun, Z.; Zha, L.; Liu, F.; He, L.; Sun, X.; Jing, X. Environmental awareness and pro-environmental behavior within China’s road freight transportation industry: Moderating role of perceived policy effectiveness. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 252, 119796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, C.; Taghian, M. Green Advertising Effects on Attitude and Choice of Advertising Themes. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2005, 17, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.A. Profiling Levels of Socially Responsible Consumer Behavior: A Cluster Analytic Approach and Its Implications for Marketing. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 1995, 3, 97–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubowiecki-Vikuk, A.; Dąbrowska, A.; Machnik, A. Responsible consumer and lifestyle: Sustainability insights. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 25, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F.G.; Biel, A. Assessing general ecological behavior: A cross-cultural comparison between switzerland and sweden. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2000, 16, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F.G.; Ranney, M.; Hartig, T.; Bowler, P.A. Ecological Behavior, Environmental Attitude, and Feelings of Responsibility for the Environment. Eur. Psychol. 1999, 4, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the Gap: Why Do People Act Environmentally and What Are the Barriers to Pro-Environmental Behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Tang, Y.; Qing, P.; Li, H.; Razzaq, A. Donation or Discount: Effect of Promotion Mode on Green Consumption Behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prothero, A.; Dobscha, S.; Freund, J.; Kilbourne, W.E.; Luchs, M.G.; Ozanne, L.K.; Thøgersen, J.; Freund, J. Sustainable Consumption: Opportunities for Consumer Research and Public Policy. J. Public Policy Mark. 2011, 30, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Ma, E.; Qu, H.; Ryan, B. Daily green behavior as an antecedent and a moderator for visitors’ pro-environmental behaviors. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1390–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarty, J.A.; Shrum, L.J. A Structural Equation Analysis of the Relationships of Personal Values, Attitudes and Beliefs About Recycling, and the Recycling of Solid Waste Products. Adv. Consum. Res. 1993, 20, 641–646. [Google Scholar]

- Namazova, N. Features of regulating the use of financial resources in Azerbaijan. In Proceedings of the 55th International Scientific Conference on Economic and Social Development, Baku, Azerbaijan, 18–19 June 2020; Volume 4, pp. 213–218. [Google Scholar]

- Schahn, J.; Holzer, E. Studies of individual environmental concern: The role of knowledge, gender, and background variables. Environ. Behav. 1990, 22, 767–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwepker, C.H.; Cornwell, T.B. An examination of ecologically concerned consumers and their intention to purchase ecologically packaged products. J. Public Policy Mark. 1991, 10, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C. New environmental theories: Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, G.; Barnes, J.H.; Montgomery, C. Ecoscale: A scale for the measurement of environmentally responsible consumers. Psychol. Mark. 1995, 12, 595–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, M.R.; Stafford, T.F.; Stafford, M.R. Green issues: Dimensions of environmental concern. J. Bus. Res. 1994, 30, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hines, M.J.; Hungerford, R.H.; Tomera, N.A. Analysis and Synthesis of Research on Responsible Environmental Behavior: A Meta-Analysis. J. Environ. Educ. 1987, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autio, M.; Heinonen, V. To consume or not to Consume? Young People’s Environmentalism in the Affluent Finnish Society. Young 2004, 12, 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreidler, N.B.; Joseph-Mathews, S. How green should you go? Understanding the role of green atmospherics in service environment evaluations. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2009, 3, 228–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasim, H.; Yan, L.; Guo, R.; Saeed, A.; Ashraf, B.N. The defining role of environmental self-identity among consumption values and behavioral intention to consume organic food. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Straughan, R.D.; Roberts, J.A. Environmental Segmentation Alternatives: A Look at Green Consumer Behaviour in the New Millennium. J. Consum. Mark. 1999, 16, 558–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Feijoo, B.; Romero, S.; Ruiz, S. Effect of stakeholders’ pressure on transparency of sustainability reports within the GRI framework. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 122, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciocirlan, C.; Pettersson, C. Does Workforce Diversity Matter in the Fight against Climate Change? An Analysis of Fortune 500 Companies. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2012, 19, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Schlegelmilchb, B.B.; Sinkovicsd, R.R.; Bohlenc, G.M. Can sociodemographics still play a role in profiling green consumers? J. Bus. Res. 2003, 56, 465–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Zheng, W. Human Exposure and Health Effects of Inorganic and Elemental Mercury. J. Prev. Med. Public Health 2012, 45, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, J. Earth Day Today. Am. Demogr. 1990, 12, 40–41. [Google Scholar]

- Roper Organization Inc. Environmental Behaviour; S.C. Johnson and Son Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Baudry, J.; Péneau, S.; Allès, B.; Touvier, M.; Hercberg, S.; Galan, P.; Amiot, M.-J.; Lairon, D.; Méjean, C.; Kesse-Guyot, E. Food choice motives when purchasing in organic and conventional consumer clusters: Focus on sustainable concerns (the nutrinet-santé cohort study). Nutrients 2017, 9, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleiner, A. What does it mean to be green? Harv. Bus. Rev. 1991, 3, 4–11. [Google Scholar]

- Roper Starch Worldwide. Green Gauge Report; Roper Starch Worldwide Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Schlossberg, H. Green marketing has been planted—Now watch it grow. Mark. News 1991, 4, 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Winski, J.M. Green marketing: Big prizes, but no easy answers. Advert. Age 1991, 62, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Barbarossa, C.; Pastore, A. Why environmentally conscious consumers do not purchase green products. Qual. Mark.Res. Int. J. 2015, 18, 188–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S.; Schmidt, P. Incentives, morality, or habit? Predicting students’ car use for university routes with the models of Ajzen, Schwartz, and Triandis. Environ. Behav. 2003, 35, 264–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarty, J.A.; Shrum, L.J. The recycling of solid wastes: Personal values, value orientations, and attitudes about recycling as antecedents of recycling behavior. J. Bus. Res. 1994, 30, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, C.; Kast, S.W. Promoting Sustainable Consumption: Determinants of Green Purchases by Swiss Consumers. Psychol. Mark. 2003, 20, 883–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widayat, W.; Praharjo, A.; Putri, V.P.; Andharini, S.N.; Masudin, I. Responsible Consumer Behavior: Driving Factors of Pro-Environmental Behavior toward Post-Consumption Plastic Packaging. Sustainability 2022, 14, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orzan, G.; Cruceru, A.F.; Bălăceanu, C.T.; Chivu, R.-G. Consumers’ Behavior Concerning Sustainable Packaging: An Exploratory Study on Romanian Consumers. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yatish, J.; Zillur, R. Factors Affecting Green Purchase Behaviour, and Future Research Directions. Int. Strateg. Manag. Rev. 2015, 3, 128–143. [Google Scholar]

- Royne, M.B.; Martinez, J.; Oakley, J.; Fox, A.K. The Effectiveness of Benefit Type and Price Endings in Green Advertising. J. Advert. 2012, 41, 85–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Sangno, L. Eco-Packaging and its Market Performance: UPC-level Sales, Brand Spillover Effects, and Curvilinearity. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radman, M. Consumer consumption and perception of organic products in Croatia. Br. Food J. 2005, 107, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lea, E.; Worsley, T. Australians’ organic food beliefs, demographics and values. Br. Food J. 2005, 107, 855–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, S. Factors influencing environmental attitudes and behaviors: A UK case study of household waste management. Environ. Behav. 2007, 39, 435–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepper, M.; Jackson, T.; Uzzell, D. An examination of the values that motivate socially conscious and frugal consumer behaviours. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2009, 33, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, I.E.; Corbin, R.M. Perceived consumer effectiveness and faith in others as moderators of environmentally responsible behaviors. J. Public Policy Mark. 1992, 11, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Agrawal, R. Environmentally responsible consumption: Construct definition, scale development, and validation. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017, 25, 523–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbarossa, C.; De Pelsmacker, P. Positive and negative antecedents of purchasing eco-friendly products: A comparison between green and non-green consumers. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 134, 229–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, S.; Gilg, A.W.; Ford, N. The household energy gap: Examining the divide between habitual-and purchase-related conservation behaviours. Energy Policy 2005, 33, 1425–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AZERTAG. Minimum Əməkhaqqı 300 Manata Çatdırılıb, Vahid Tarif Cədvəli Üzrə. Available online: https://azertag.az/xeber/Minimum_emekhaqqi_300_manata_chatdirilib_vahid_tarif_cedveli_uzre_isleyenlerin_emekhaqqi_artirilib-1954354. (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Leonidou, N.C.; Katsikeas, S.C.; Morgan, A.N. ‘Greening’ the marketing mix: Do firms do it and does it pay off? J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2013, 41, 151–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liobikienė, G.; Grincevičienė, Š.; Bernatonienė, J. Environmentally friendly behaviour and green purchase in Austria and Lithuania. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 3789–3797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogarty, K.Y.; Hines, C.V.; Kromrey, J.D.; Ferron, J.M.; Mumford, K.R. The quality of factor solutions in exploratory factor analysis: The influence of sample size, communality and overdetermination. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2005, 65, 202–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, J.P. Applied Multivariate Statistics for the Social Sciences, 4th ed; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum, R.C.; Widaman, K.F.; Zhang, S.; Hong, S. Sample size in factor analysis. Psychol. Methods 1999, 4, 84–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, L.S.; Kulshrestha, P. Performing the KMO and Bartlett’s Test for Factors Estimating the Warehouse Efficiency, Inventory and Customer Contentment for E-retail Supply Chain. Int. J. Res. Eng. Appl. Manag. 2019, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Gautam, V. Examining environmental friendly behaviors of tourists towards sustainable development. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 276, 111292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zeynalova, Z.; Namazova, N. Revealing Consumer Behavior toward Green Consumption. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5806. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14105806

Zeynalova Z, Namazova N. Revealing Consumer Behavior toward Green Consumption. Sustainability. 2022; 14(10):5806. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14105806

Chicago/Turabian StyleZeynalova, Zivar, and Natavan Namazova. 2022. "Revealing Consumer Behavior toward Green Consumption" Sustainability 14, no. 10: 5806. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14105806

APA StyleZeynalova, Z., & Namazova, N. (2022). Revealing Consumer Behavior toward Green Consumption. Sustainability, 14(10), 5806. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14105806