Impact of ICTs on Innovation and Performance of Firms: Do Start-ups, Regional Proximity and Skills Matter?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Resource-Based View (RBV) Framework

2.2. ICT, Innovation, and Firm Performance

2.3. Start-ups, Innovation, and Performance

3. Research Method

3.1. Data and Sample

3.2. Methods

| Variable | Definition | Mean | Std. Dev. | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Innovation | A dummy variable indicating whether a firm is innovative (1) or not (0). | 0.5148 | 0.5007 | Gërguri-Rashiti, Ramadani [37], Yunis, El-Kassar [38] |

| Profitability | A multinominal categorical variable indicating the profitability of a firm (3-point scale from 1 = ‘unprofitable’ to 3 = ‘above average profitable’). | 2.2556 | 0.5567 | Huang, Lai [111], Steinfield- et al. [112] |

| Relative performance | A multinominal categorical variable indicating (3-point scale from 1 = ‘worse’ to 3 = ‘better’). | 2.4000 | 0.5936 | Steinfield et al. [112] |

| Financial performance | A composite index developed to measure the level of overall financial performance of a firm using PCA. It is a composite measure of two indicators: (i) profitability and (ii) relative performance. The outcome of PCA is the composite indicator—the overall financial performance of a firm (3-point scale from 1 = ‘bad’ to 3 = ‘good’). | 2.3278 | 0.4572 | Huang, Lai [111], Steinfield et al. [112] |

| ICT skills | A multinominal variable indicates the extensity of ICT skills of employees required to conduct day-to-day business activities (5-point scale from 1 = ‘very low’ to 5 = ‘very high’). | 2.9259 | 1.3990 | Yunis et al. [38] |

| Agile management culture | Agile management culture is measured on 5-point Likert scale questions. The item is based on ‘Our work environment is a positive and friendly place to be’ (5-point scale from 1 = ‘not true at all’ to 5 = ‘very true’). | 3.5185 | 0.8696 | Naranjo-Valencia et al. [113] |

| Internationalization | A multinominal variable indicates the share of revenue of a firm from international export activities. | 2.0370 | 0.7847 | Loth and Parks [114], Pangarkar [115] |

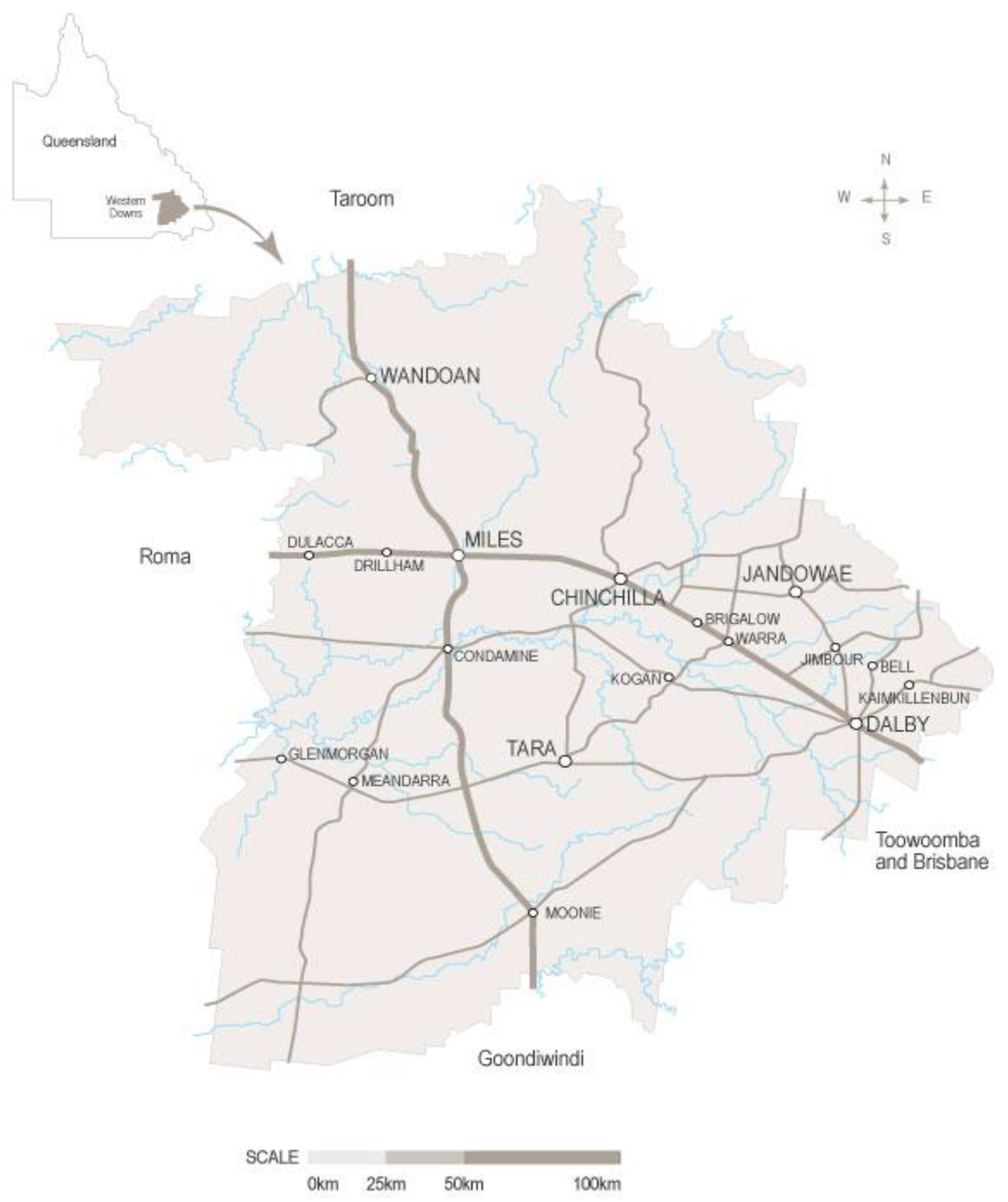

| Remoteness | A dummy variable indicating whether a firm is located in rural and remote areas (1), namely, Miles, Moraby, Cardamine, Wandoan, Cockatoo, Tara, Goranba, Teelba, Glenmorgan, Dillham, and Lenaubyn, or in major town centers (0). | 0.7407 | 0.4390 | Stockdale and Standing [116] |

| Start-up | A dummy variable indicating whether a firm has remained in the business for 5 years with employees of fewer than 6 persons (1) or not (0). | 0.1593 | 0.3666 | Colombelli, Krafft [117], Katila and Shane [118], Criscuolo, Nicolaou [119] |

| ICT strategy | A dummy variable indicating whether a firm has an ICT strategy (1) or not (0). | 0.2222 | 0.4165 | Gërguri-Rashiti, Ramadani [37], Yunis, El-Kassar [38] |

| Number of employees | Number of employees currently working in the enterprise. | 8.2963 | 16.6153 | Gërguri-Rashiti et al. [37] |

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Drivers of Innovation

4.2. Drivers of Performance

4.3. Robustness Checks

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

6. Implications for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chege, S.M.; Wang, D.; Suntu, S.L. Impact of information technology innovation on firm performance in Kenya. Inf. Technol. Dev. 2020, 26, 316–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langley, D.J.; van Doorn, J.; Ng, I.C.; Stieglitz, S.; Lazovik, A.; Boonstra, A. The Internet of Everything: Smart things and their impact on business models. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 122, 853–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristofaro, M. E-business evolution: An analysis of mobile applications’ business models. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2020, 32, 88–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haaker, T.; Ly, P.T.M.; Nguyen-Thanh, N.; Nguyen, H.T.H. Business model innovation through the application of the Internet-of-Things: A comparative analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 126, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, S.; Michael, K.; Uddin, M.R.; McCarthy, G.; Rahman, M. Transforming business using digital innovations: The application of AI, blockchain, cloud and data analytics. Ann. Oper. Res. 2020, 308, 7–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, N. Demystifying blockchain: A critical analysis of challenges, applications and opportunities. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 54, 102120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Gaudio, B.L.; Porzio, C.; Sampagnaro, G.; Verdoliva, V. How do mobile, internet and ICT diffusion affect the banking industry? An empirical analysis. Eur. Manag. J. 2021, 39, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Gupta, S.; Sun, W.; Zou, Y. How social-media-enabled co-creation between customers and the firm drives business value? The perspective of organizational learning and social Capital. Inf. Manag. 2020, 57, 103200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Counts of Australian Business 8165.0. 2019. Available online: https://www.asbfeo.gov.au/sites/default/files/Small_Business_Statistical_Report-Final.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2022).

- Ali Qalati, S.; Li, W.; Ahmed, N.; Ali Mirani, M.; Khan, A. Examining the factors affecting SME performance: The mediating role of social media adoption. Sustainability 2021, 13, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marion, T.J.; Fixson, S.K. The Transformation of the Innovation Process: How Digital Tools are Changing Work, Collaboration, and Organizations in New Product Development. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2021, 38, 192–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzi, S.; Corbo, L.; Caputo, A. Fintech and SMEs sustainable business models: Reflections and considerations for a circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 281, 125217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostis, A.; Ritala, P. Digital artifacts in industrial co-creation: How to use VR technology to bridge the provider-customer boundary. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2020, 62, 125–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranta, V.; Aarikka-Stenroos, L.; Väisänen, J.M. Digital technologies catalyzing business model innovation for circular economy—Multiple case study. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 164, 105155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton, J.; Jinkins, D.; Tybout, J.R.; Xu, D. Two-Sided Search in International Markets; Working Paper 29684; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chege, S.M.; Wang, D. The influence of technology innovation on SME performance through environmental sustainability practices in Kenya. Technol. Soc. 2020, 60, 101210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaBerge, L.; O’Toole, C.; Schneider, J.; Smaje, K. How COVID-19 Has Pushed Companies over the Technology Tipping Point and Transformed Business Forever. McKinsey & Company. 2020. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/how-covid-19-has-pushed-companies-over-the-technology-tipping-point-and-transformed-business-forever (accessed on 16 March 2022).

- Alam, K.; Adeyinka, A.A.; Wiesner, R. Smaller businesses and e-innovation: A winning combination in Australia. J. Bus. Strategy 2019, 41, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Gao, P.; Chimhowu, A. ICTs in the transformation of rural enterprises in China: A multi-layer perspective. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2019, 145, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, R.; Kowalkiewicz, M.; Shahiduzzaman, M. High Growth and Technology: Case Studies of Queensland Firms in the Digital Economy; Department of Science, Information Technology and Innovation, Queensland Government: Brisbane, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Western Downs Regional Council (WDRC). Economic Profile. 2019. Available online: https://economy.id.com.au/western-downs/gross-product (accessed on 8 July 2019).

- Alexy, O.; West, J.; Klapper, H.; Reitzig, M. Surrendering control to gain advantage: Reconciling openness and the resource-based view of the firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 2018, 39, 1704–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, P.E.; Bendickson, J.S. Strategic antecedents of innovation: Variance between small and large firms. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2021, 59, 47–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnellan, J.; Rutledge, W.L. A case for resource-based view and competitive advantage in banking. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2019, 40, 728–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimenez-Fernandez, E.M.; Sandulli, F.D.; Bogers, M. Unpacking liabilities of newness and smallness in innovative start-ups: Investigating the differences in innovation performance between new and older small firms. Res. Policy 2020, 49, 104049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuckertz, A.; Brändle, L.; Gaudig, A.; Hinderer, S.; Reyes, C.A.M.; Prochotta, A.; Steinbrink, K.M.; Berger, E.S. Start-ups in times of crisis–A rapid response to the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Bus. Ventur. Insights 2020, 13, e00169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamzadeh, A.; Dana, L.P. The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic: Challenges among Iranian start-ups. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 2021, 33, 489–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukaatmadja, I.; Yasa, N.; Rahyuda, H.; Setini, M.; Dharmanegara, I. Competitive advantage to enhance internationalization and marketing performance woodcraft industry: A perspective of resource-based view theory. J. Proj. Manag. 2021, 6, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, C.V. Strategic choices: Accelerated start-ups’ outsourcing decisions. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 105, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marullo, C.; Casprini, E.; Di Minin, A.; Piccaluga, A. ‘Ready for Take-off’: How Open Innovation influences start-up success. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2018, 27, 476–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangarkar, N.; Wu, J. Alliance formation, partner diversity, and performance of Singapore start-ups. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2013, 30, 791–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q. New-born start-ups performance: Influences of resources and entrepreneurial team experiences. Int. Bus. Res. 2018, 11, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bianchi, C.; Mingo, S.; Fernandez, V. Strategic management in Latin America: Challenges in a changing world. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 105, 306–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caseiro, N.; Coelho, A. The influence of Business Intelligence capacity, network learning and innovativeness on start-ups performance. J. Innov. Knowl. 2019, 4, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, S.; Cotei, C.; Farhat, J. A resource-based view of new firm survival: New perspectives on the role of industry and exit route. J. Dev. Entrep. 2013, 18, 1350002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-Y.K.; Jaw, Y.-L.; Wu, B.-L. Effect of digital transformation on organizational performance of SMEs: Evidence from the Taiwanese textile industry’s web portal. Internet Res. 2016, 26, 186–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gërguri-Rashiti, S.; Ramadani, V.; Abazi-Alili, H.; Dana, L.P.; Ratten, V. ICT, Innovation and Firm Performance: The Transition Economies Context. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2017, 59, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunis, M.; El-Kassar, A.-N.; Tarhini, A. Impact of ICT-based innovations on organizational performance: The role of corporate entrepreneurship. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2017, 30, 122–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenamor, J.; Parida, V.; Wincent, J. How entrepreneurial SMEs compete through digital platforms: The roles of digital platform capability, network capability and ambidexterity. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 100, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neirotti, P.; Raguseo, E.; Paolucci, E. How SMEs develop ICT-based capabilities in response to their environment: Past evidence and implications for the uptake of the new ICT paradigm. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2018, 31, 10–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Kundu, A.; Bhattacharya, A. Technology Adaptation and Survival of SMEs: A Longitudinal Study of Developing Countries. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2020, 10, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, L.; Shutt, J.; Sellick, J. Supporting rural Small and Medium-sized Enterprises to take up broadband-enabled technology: What works? Local Econ. 2018, 33, 515–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvanitis, S.; Loukis, E.N. Investigating the effects of ICT on innovation and performance of European hospitals: An exploratory study. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2016, 17, 403–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Skare, M.; Soriano, D.R. How globalization is changing digital technology adoption: An international perspective. J. Innov. Knowl. 2021, 6, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas-Vargas, H.; Estrada, S.; Larios-Gómez, E. The effects of ICTs as innovation facilitators for a greater business performance. Evidence from Mexico. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2016, 91, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taştan, H.; Gönel, F. ICT labor, software usage, and productivity: Firm-level evidence from Turkey. J. Product. Anal. 2020, 53, 265–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leviäkangas, P.; Paik, S.M.; Moon, S. Keeping up with the pace of digitization: The case of the Australian construction industry. Technol. Soc. 2017, 50, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indriastuti, M.; Fuad, K. Impact of COVID-19 on digital transformation and sustainability in small and medium enterprises (SMEs): A conceptual framework. In Conference on Complex, Intelligent, and Software Intensive Systems; Springer: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, H.; Yang, Z.; Huang, R.; Guo, A. The digitalization and public crisis responses of small and medium enterprises: Implications from a COVID-19 survey. Front. Bus. Res. China 2020, 14, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpan, I.J.; Udoh, E.A.P.; Adebisi, B. Small business awareness and adoption of state-of-the-art technologies in emerging and developing markets, and lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 2022, 34, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakopoulos, G.; Solovev, D. Circular Economy (CE) Innovation and Internationalization of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs): Geographical Overview and Sectorial Patterns. In Proceeding of the International Science and Technology Conference “FarEastCon 2021”; Springer: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Balboni, B.; Bortoluzzi, G.; Pugliese, R.; Tracogna, A. Business model evolution, contextual ambidexterity and the growth performance of high-tech start-ups. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 99, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarillo, J.C. On Strategic Networks. Strateg. Manag. J. 1988, 9, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorgren, S.; Wincent, J.; Ortqvist, D. Designing interorganizational networks for innovation:an empirical examination of network configuration, formation and governance. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. 2009, 26, 148–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Man, A.P.; Duysters, G. Collaboration and innovation: A review of the effects of mergers, acquisitions and alliances on innovation. Technovation 2005, 25, 1377–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, M.G.A.; Solis, E.R.R.; Zhu, J.J. Innovation and network multiplexity: R&D and the concurrent effects of two collaboration networks in an emerging economy. Res. Policy 2018, 47, 1111–1124. [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Rojas, R.; García-Morales, V.J.; Garrido-Moreno, A.; Salmador-Sánchez, M.P. Social media use and the challenge of complexity: Evidence from the technology sector. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 129, 621–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vătamănescu, E.-M.; Cegarra-Navarro, J.-G.; Andrei, A.G.; Dincă, V.-M.; Alexandru, V.-A. SMEs strategic networks and innovative performance: A relational design and methodology for knowledge sharing. J. Knowl. Manag. 2020, 24, 1367–3270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrò, A.; Vecchiarini, M.; Gast, J.; Campopiano, G.; De Massis, A.; Kraus, S. Innovation in family firms: A systematic literature review and guidance for future research. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2019, 21, 317–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feranita, F.; Kotlar, J.; De Massis, A. Collaborative innovation in family firms: Past research, current debates and agenda for future research. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2017, 8, 137–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alarussi, A.S.; Alhaderi, S.M. Factors affecting profitability in Malaysia. J. Econ. Stud. 2018, 45, 442–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alshehhi, A.; Nobanee, H.; Khare, N. The impact of sustainability practices on corporate financial performance: Literature trends and future research potential. Sustainability 2018, 10, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Habtay, S.R. A firm-level analysis on the relative difference between technology-driven and market-driven disruptive business model innovations. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2012, 21, 290–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haneberg, D.H. How combinations of network participation, firm age and firm size explain SMEs’ responses to COVID-19. Small Enterp. Res. 2021, 28, 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amezcua, A.S.; Grimes, M.G.; Bradley, S.W.; Wiklund, J. Organizational sponsorship and founding environments: A contingency view on the survival of business-incubated firms, 1994–2007. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 1628–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mian, S.; Lamine, W.; Fayolle, A. Technology business incubation: An overview of the state of knowledge. Technovation 2016, 50–51, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiriz, V.; Gonçalves, M.; Areias, J.S. Inter-organizational learning within an institutional knowledge network: A case study in the textile and clothing industry. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2017, 20, 230–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giones, F.; Brem, A.; Pollack, J.M.; Michaelis, T.L.; Klyver, K.; Brinckmann, J. Revising entrepreneurial action in response to exogenous shocks: Considering the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Bus. Ventur. Insights 2020, 14, e00186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henley, A.; Song, M. Innovation, internationalization and the performance of microbusinesses. Int. Small Bus. J. 2020, 38, 337–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morais, F.; Ferreira, J.J. SME internationalization process: Key issues and contributions, existing gaps and the future research agenda. Eur. Manag. J. 2020, 38, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falahat, M.; Ramayah, T.; Soto-Acosta, P.; Lee, Y.Y. SMEs internationalization: The role of product innovation, market intelligence, pricing and marketing communication capabilities as drivers of SMEs’ international performance. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 152, 119908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, B.; Qian, G. The belt and road initiative, cultural friction and ethnicity: Their effects on the export performance of SMEs in China. J. World Bus. 2019, 54, 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F.; Paul, J.; Fayolle, A. SMEs and entrepreneurship in the era of globalization: Advances and theoretical approaches. Small Bus. Econ. 2020, 55, 695–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Deng, P. Internationalization of SMEs from emerging markets: An institutional escape perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 108, 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jogaratnam, G. How organizational culture influences market orientation and business performance in the restaurant industry. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2017, 31, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roscoe, S.; Subramanian, N.; Jabbour, C.J.; Chong, T. Green human resource management and the enablers of green organizational culture: Enhancing a firm’s environmental performance for sustainable development. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 737–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, F.; Xiu, G.; Shahbaz, M. Organizational culture and innovation performance in Pakistan’s software industry. Technol. Soc. 2017, 51, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, L.M.; Charlier, S.D.; Brown, K.G. Trading off learning and performance: Exploration and exploitation at work. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2019, 29, 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heras, H.A.; Estensoro, M.; Larrea, M. Organizational ambidexterity in policy networks. Compet. Rev. Int. Bus. J. 2020, 30, 219–242. [Google Scholar]

- Ardito, L.; Besson, E.; Petruzzelli, A.M.; Gregori, G.L. The influence of production, IT, and logistics process innovations on ambidexterity performance. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2018, 24, 1271–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rialti, R.; Marzi, G.; Silic, M.; Ciappei, C. Ambidextrous organization and agility in big data era. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2018, 24, 1091–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alam, K.; Imran, S. The digital divide and social inclusion among refugee migrants: A case in regional Australia. Inf. Technol. People 2015, 28, 344–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Erdiaw-Kwasie, M.O.; Alam, K. Towards understanding digital divide in rural partnerships and development: A framework and evidence from rural Australia. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 43, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, S.; Walker, C. From the interpersonal to the internet: Social service digitisation and the implications for vulnerable individuals and communities. Aust. J. Political Sci. 2018, 53, 490–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S. Digital inequalities in rural Australia: A double jeopardy of remoteness and social exclusion. J. Rural Stud. 2017, 54, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, K.; Adeyinka, A.A. Does innovation stimulate performance? The case of small and medium enterprises in regional Australia. Aust. Econ. Pap. 2021, 60, 496–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, K.; Ali, M.A.; Erdiaw-Kwasie, M.O.; Murray, P.A.; Wiesner, R. Digital transformation among SMEs: Does gender matter? Sustainability 2022, 14, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, S. Australia’s Digital Divide is Narrowing, but Getting Deeper. 2016. Available online: http://theconversation.com/australias-digital-divide-is-narrowing-but-getting-deeper-55232 (accessed on 18 May 2019).

- Philip, L.; Williams, F. Remote rural home-based businesses and digital inequalities: Understanding needs and expectations in a digitally underserved community. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 68, 306–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assante, D.; Castro, M.; Hamburg, I.; Martin, S. The use of cloud computing in SMEs. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2016, 83, 1207–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ebersberger, B.; Kuckertz, A. Hop to it! The impact of organization type on innovation response time to the COVID-19 crisis. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 124, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, D.; Potts, J. Innovation Strangled by Red Tape. Submission to the Productivity Commission Inquiry into Business Set-Up, Transfer and Closure. Australian Government, Canberra. 2015. Available online: https://ipa.org.au/wp-content/uploads/archive/200215_Submission-DA-innovation_strangled_by_red_tape.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2019).

- Ali, M.A.; Alam, K.; Taylor, B. Do social exclusion and remoteness explain the digital divide in Australia? Evidence from a panel data estimation approach. Econ. Innov. New Technol. 2020, 29, 643–659. [Google Scholar]

- Bosma, N.; Sanders, M.; Stam, E. Institutions, entrepreneurship, and economic growth in Europe. Small Bus. Econ. 2018, 51, 483–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gherghina, Ș.C.; Botezatu, M.A.; Hosszu, A.; Simionescu, L.N. Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs): The engine of economic growth through investments and innovation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ghezzi, A.; Cavallo, A. Agile business model innovation in digital entrepreneurship: Lean startup approaches. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 110, 519–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombelli, A.; Krafft, J.; Vivarelli, M. To be born is not enough: The key role of innovative start-ups. Small Bus. Econ. 2016, 47, 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Coad, A.; Holm, J.R.; Krafft, J.; Quatraro, F. Firm age and performance. J. Evol. Econ. 2018, 28, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jiang, W.; Wang, A.X.; Zhou, K.Z.; Zhang, C. Stakeholder relationship capability and firm innovation: A contingent analysis. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 167, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petruzzelli, A.M.; Ardito, L.; Savino, T. Maturity of knowledge inputs and innovation value: The moderating effect of firm age and size. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 86, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayo-Moriones, A.; Billón, M.; Lera-López, F. Perceived performance effects of ICT in manufacturing SMEs. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2013, 113, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bertschek, I.; Cerquera, D.; Klein, G.J. More bits–more bucks? Measuring the impact of broadband internet on firm performance. Inf. Econ. Policy 2013, 25, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tarutė, A.; Gatautis, R. ICT impact on SMEs performance. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 110, 1218–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Melville, N.; Kraemer, K.; Gurbaxani, V. Review: Information technology and organizational performance: An integrative model of IT business value. MIS Q. 2004, 28, 283–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brynjolfsson, E.; Saunders, A. Wired for Innovation: How Information Technology is Reshaping the Economy; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Koellinger, P. The relationship between technology, innovation, and firm performance-Empirical evidence from e-business in Europe. Res. Policy 2008, 37, 1317–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hosseini, H.M.; Kaneko, S. Dynamic sustainability assessment of countries at the macro level: A principal component analysis. Ecol. Indic. 2011, 11, 811–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, R.P.; Arvin, M.B.; Norman, N.R.; Bele, S.K. Economic growth and the development of telecommunications infrastructure in the G-20 countries: A panel-VAR approach. Telecommun. Policy 2014, 38, 634–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyoum, S. Analysis of prevalence of malaria and anaemia using bivariate probit model. Ann. Data Sci. 2018, 5, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Torres, A.P.; Marshall, M.I.; Alexander, C.E.; Delgado, M.S. Are local market relationships undermining organic fruit and vegetable certification? A bivariate probit analysis. Agric. Econ. 2017, 48, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.-C.; Lai, M.-C.; Lo, K.-W. Do founders’ own resources matter? The influence of business networks on start-up innovation and performance. Technovation 2012, 32, 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinfield, C.; LaRose, R.; Chew, H.E.; Tong, S.T. Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises in Rural Business Clusters: The Relation between ICT Adoption and Benefits Derived from Cluster Membership. Inf. Soc. 2012, 28, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naranjo-Valencia, J.C.; Jiménez-Jiménez, D.; Sanz-Valle, R. Studying the links between organizational culture, innovation, and performance in Spanish companies. Rev. Latinoam. Psicol. 2016, 48, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Loth, F.; Parks, T. The impact of foreign operations on organizational performance. Int. J. Manag. 2002, 19, 418–428. [Google Scholar]

- Pangarkar, N. Internationalization and performance of small-and medium-sized enterprises. J. World Bus. 2008, 43, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockdale, R.; Standing, C. Benefits and barriers of electronic marketplace participation: An SME perspective. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2004, 17, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Colombelli, A.; Krafft, J.; Vivarelli, M. Entrepreneurship and Innovation: New Entries, Survival, Growth; Work in progress in the Groupe de Recherche en Droit, Economie et Gestion (GREDEG); University of Nice-Shopia Antipolis: Nice, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Katila, R.; Shane, S. When does a lack of resources make new firms innovative? Acad. Manag. J. 2005, 48, 814–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Criscuolo, P.; Nicolaou, N.; Salter, A. The elixir (or burden) of youth? Exploring differences in innovation between start-ups and established firms. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juergensen, J.; Guimón, J.; Narula, R. European SMEs amidst the COVID-19 crisis: Assessing impact and policy responses. J. Ind. Bus. Econ. 2020, 47, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macpherson, A.; Holt, R. Knowledge, learning and small firm growth: A systematic review of the evidence. Res. Policy 2007, 36, 172–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smallbone, D.; Deakins, D.; Battisti, M.; Kitching, J. Small business responses to a major economic downturn: Empirical perspectives from New Zealand and the United Kingdom. Int. Small Bus. J. 2012, 30, 754–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoben, J.; Oerlemans, L.A.G. Proximity and inter-organizational collaboration: A literature review. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2006, 8, 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Loebbecke, C.; van Fenema, P.C.; Powell, P. Managing inter-organizational knowledge sharing. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2016, 25, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paulraj, A.; Lado, A.A.; Chen, I.J. Inter-organizational communication as a relational competency: Antecedents and performance outcomes in collaborative buyer-supplier relationships. J. Oper. Manag. 2008, 26, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, P.A. The domains of intellectual capital: An integrative discourse across perspectives. In The Palgrave Handbook of Knowledge Management; Syed, J., Murray, P.A., Hislop, D., Mouzughi, Y., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Camden, UK, 2018; pp. 21–52. [Google Scholar]

- Dyer, J.H.; Singh, H. The relational view: Cooperative strategy and sources of interorganizational competitive advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 660–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dyer, J.H.; Singh, H.; Hesterly, W.S. The relational view revisited: A dynamic perspective on value creation and value capture. Strateg. Manag. J. 2018, 39, 3140–3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Era, C.; Marchesi, A.; Verganti, R. Mastering technologies in design-driven innovation. Res. -Technol. Manag. 2010, 53, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zortea-Johnston, E.; Darroch, J.; Matear, S. Business orientations and innovation in small and medium sized enterprises. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2012, 8, 145–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Kumar, V.; Karam, E. New-age technologies-driven social innovation: What, how, where, and why? Ind. Mark. Manag. 2019, 89, 499–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.A.; Khan, A.N. What followers are saying about transformational leaders fostering employee innovation via organizational learning, knowledge sharing and social media use in public organisations? Gov. Inf. Q. 2019, 36, 101391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, G.; Quaglia, R.; Pellicelli, A.C.; De Bernardi, P. The interplay among entrepreneur, employees, and firm level factors in explaining SMEs openness: A qualitative micro-foundational approach. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 151, 119820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H.; Bogers, M. Explicating open innovation: Clarifying an emerging paradigm for understanding innovation. In New Frontiers in Open Innovation; Chesbrough, H., Vanhaverbeke, W., West, J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

| Dependent Variable: Innovation | Models | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | |

| Financial performance | 0.6989 * | 0.1873 | 0.6618 * | 0.1909 | 0.6500 * | 0.1911 |

| ICT skills | 0.2644 * | 0.0608 | 0.2577 * | 0.0616 | 0.2109 * | 0.0706 |

| Agile management culture | 0.1720 *** | 0.0946 | 0.1776 *** | 0.0956 | 0.1991 ** | 0.0973 |

| Internationalization | 0.1417 | 0.1105 | 0.1467 | 0.1127 | 0.1403 | 0.1118 |

| Remoteness | −0.4161 ** | 0.1899 | −0.4289 | 0.1946 | −0.4657 ** | 0.1929 |

| Start-up | −0.1953 *** | 0.5126 | ||||

| Start-up × ICT skills | 0.0728 *** | 0.1635 | ||||

| ICT strategy | 0.4746 ** | 0.2181 | ||||

| Industry agriculture | −0.2996 | 0.3401 | ||||

| Industry manufacturing | 0.5625 ** | 0.3333 | ||||

| Industry services | 0.1921 | 0.3046 | ||||

| Constant | −2.9466 * | 0.5097 | −2.5832 * | 0.6449 | −2.8330 * | 0.5768 |

| LR chi-squared | 53.1000 * | 57.1400 * | 57.9600 * | |||

| Pseudo R-squared | 0.1419 | 0.1528 | 0.1594 | |||

| N | 270 | 270 | 270 | |||

| Variables | Dependent Variable: Innovation | |

|---|---|---|

| Coef. | Robust SE | |

| Financial performance | 0.4593 * | 0.0613 |

| ICT skills | 0.0849 * | 0.0205 |

| Agile management culture | 0.0443 * | 0.0337 |

| Internationalization | 0.0320 | 0.0358 |

| Remoteness | −0.1806 * | 0.0651 |

| Start-up | −0.0156 ** | 0.0774 |

| Constant | −0.8927 | 0.1791 |

| Chi-squared | 101.0000 * | |

| R-squared | 0.1452 | |

| N | 270 | |

| Variables | Dependent Variable: Financial Performance | |

|---|---|---|

| Coef. | SE | |

| Innovation | 0.4066 * | 0.0542 |

| ICT skills | 0.0099 | 0.0202 |

| Agile management culture | 0.0421 ** | 0.0316 |

| Internationalization | 0.0193 | 0.0341 |

| Remoteness | 0.1875 * | 0.0615 |

| Start-up | −0.0877 | 0.0728 |

| No of employees | 0.0025 *** | 0.0016 |

| Constant | 1.8147 * | 0.1343 |

| Chi-squared | 83.8200 * | |

| R-squared | 0.0978 | |

| N | 270 | |

| Variables | Dependent Variable: Innovation | |

|---|---|---|

| Coef. | SE | |

| Financial performance | 0.6968 * | 0.1880 |

| ICT skills | 0.2638 * | 0.0610 |

| Agile management culture | 0.1743 *** | 0.0960 |

| Internationalization | 0.1408 | 0.1107 |

| Remoteness | −0.4134 ** | 0.1909 |

| Start-up | −0.0313 | 0.2293 |

| Constant | −2.9430 * | 0.5664 |

| Variables | Dependent variable: Financial performance | |

| Coef. | SE | |

| Innovation | 0.2141 * | 0.0556 |

| ICT skills | 0.0091 | 0.0203 |

| Agile management culture | 0.0572 *** | 0.0317 |

| Internationalization | 0.0290 | 0.0342 |

| Remoteness | 0.1651 * | 0.0615 |

| Start-up | −0.0935 | 0.0729 |

| No of employees | 0.0027 *** | 0.0017 |

| Constant | 1.8007 | 0.1343 |

| Log likelihood | −154.5615 | |

| LR chi-squared | 39.5400 * | |

| N | 270 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alam, K.; Ali, M.A.; Erdiaw-Kwasie, M.; Shahiduzzaman, M.; Velayutham, E.; Murray, P.A.; Wiesner, R. Impact of ICTs on Innovation and Performance of Firms: Do Start-ups, Regional Proximity and Skills Matter? Sustainability 2022, 14, 5801. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14105801

Alam K, Ali MA, Erdiaw-Kwasie M, Shahiduzzaman M, Velayutham E, Murray PA, Wiesner R. Impact of ICTs on Innovation and Performance of Firms: Do Start-ups, Regional Proximity and Skills Matter? Sustainability. 2022; 14(10):5801. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14105801

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlam, Khorshed, Mohammad Afshar Ali, Michael Erdiaw-Kwasie, Md Shahiduzzaman, Eswaran Velayutham, Peter A. Murray, and Retha Wiesner. 2022. "Impact of ICTs on Innovation and Performance of Firms: Do Start-ups, Regional Proximity and Skills Matter?" Sustainability 14, no. 10: 5801. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14105801

APA StyleAlam, K., Ali, M. A., Erdiaw-Kwasie, M., Shahiduzzaman, M., Velayutham, E., Murray, P. A., & Wiesner, R. (2022). Impact of ICTs on Innovation and Performance of Firms: Do Start-ups, Regional Proximity and Skills Matter? Sustainability, 14(10), 5801. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14105801