Abstract

Current studies on how a sustainability leadership theory can influence the practice of SMEs, such as a context of community-based social enterprises, is still lacking, with scanty research to date. These small enterprises in the bottom of the pyramid settings are indeed the important socio-economic backbone of many nations around the world. The COVID-19 pandemic crisis has significantly hit all sectors and has adversely impacted them. Our study aims to broaden the limited scholarly knowledge and advance the developing SL theory in this realm. Hence, our critical research inquiries address: (1) What are the essential sustainable leadership practices and sustainability competencies for sustainability and resilience in a CBSE context? (2) How can a CBSE business apply the theoretical frameworks in practice to survive and thrive for sustainable futures, especially during the COVID-19 era? This study employs an integrative theoretical examination of sustainable leadership frameworks and sustainability leadership competencies to investigate the sustainable business practices in the SME sector, particularly in a community-based social enterprise context. Our business case centers on a green, social enterprise, which is an award-winner of Best Responsible Tourism and is located in a small coastal fishing village of Thailand. Using a case study research method, the multi-data collection methods include in-depth interviews and focus groups with multiple stakeholders. Evidence was found to comply with six-category sustainable leadership practices and five essential sustainability leadership competencies to varying degrees. The findings suggest that sustainable leaders and entrepreneurs should develop and integrate the value-based practices and competencies (i.e., strategic, systems thinking, interpersonal, anticipatory, ethical competencies) in business. The critical sustainable practices include enabling human capital with care for stakeholders, fostering ethical values and norms via altruism, cultivating social capital through social innovation, and supporting pro-environmental behavior and social responsibility to achieve inclusive growth, sustainability and resilience. The research results advance the theoretical development of the interconnected fields of sustainability leadership and sustainable entrepreneurship. An alternative sustainable business model for sustainability and resilience is also proposed. Overall, the insightful findings can provide practical advice and beneficial policy implications for sustainable futures.

1. Introduction

Sustainability leadership has gained much popularity as an emergent multidisciplinary area in the recent literature. Worldwide scholars call for more sustainability studies as an important leadership agenda [1,2,3,4]. Modern leaders need to strategically lead their businesses beyond profit-maximization or economic performance and maneuver their vision and strategy toward environmental protection and social responsibility [5,6]. The literature urges future leaders and managers to purposefully develop value-oriented sustainable leadership and sustainability competencies in their business practices as well as to balance the economic performance and socio-environmental responsibility to thrive for long-term success [7,8,9,10,11]. The latest empirical research also indicates that sustainability leadership is a key determinant of long-term success and sustainability performance outcomes [12,13]. The topic strategically becomes critical to achieve corporate resilience, longevity and sustainable futures.

The rise of the global sustainable development aspiration, such as the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs), has further attracted international leaders and policy-makers to reorient their leadership paradigm towards sustainability. Further, the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic crisis has severely affected all sectors, particularly small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and disadvantaged communities with limited capital funding and resource constraints [14,15,16]. The pandemic has indeed been a catalyst for an integrative lens on leadership for sustainability or sustainability leadership transformations [13]. The crisis is also pressing all leaders, entrepreneurs and managers to transform their visions and sustainable strategies as well as to incorporate SDGs into their missions with better balance of the economic, ecological and social triads [17,18].

In the leadership field, sustainability has greatly influenced contemporary organizational leadership and management studies. A recent bibliometric review of sustainable leadership from the worldwide scholarship by Hallinger & Suriyankietkaew [5] indicates the emergence of new theoretical models of leadership and sustainability over the past decades. The terms (i.e., sustainability leadership or sustainable leadership) are often used interchangeably for parsimony. The review reinforces the importance of sustainability-oriented leadership values towards sustainable futures [5]. Previous researchers also highlighted further integration of multidimensional facets of leadership and sustainability to advance this emergent field of inquiry [7,19,20]. One critical leadership view concerning sustainability puts forward the importance of social, ethical and responsible business conduct with multiple stakeholder engagement [9,21,22,23]. The literature urged that contemporary leadership should extend beyond the popular green and social notions of corporate sustainability, such as corporate social responsibility (CSR), corporate responsibility (CR) and triple bottom line (TBL) [24]. Another modernized perspective puts leadership and management processes at the heart of achieving long-term well-being and enduring value for all stakeholders, beyond just social and environmental sustainability, such as a theoretical framework of sustainable leadership offers [7,19]. In this paper, we thus undertake ‘sustainable leadership’ as the integrative theoretical leadership framework for corporate resilience and sustainability. In addition, we seek to advance the theoretical development by investigating necessary leadership competencies that are needed to develop contemporary sustainability leadership.

Moreover, the literature highlights the importance of SMEs, particularly social enterprises (SE), as the socio-economic backbone in most countries [25]. Since the introduction of the idea of “social business” by Muhammad Yunus in the early 1980s, social enterprises have grown in their global significance and have attracted many academic researchers, practitioners and policymakers worldwide [26]. They are defined as businesses organizations with primary focus on delivering social or environmental benefits in a self-sustaining way [27]. One distinctive form of SE is community-based social enterprises (CBSE). Researchers [28,29] highlight the importance of CBSEs as an alternative self-reliant, self-sufficient business model for sustainable development. CBSEs are non-profit, independent organizations with a unique geographical characteristic, wherein community members own and operate their business to earn incomes from self-managed community-based activities that contribute to the local development and well-being of the community [30,31,32]. In the CBSE context, leadership is the most critical success factor to help detect any coming opportunities and risks while mobilizing capital and capacities to realize community and social benefits [33]. They are indeed essential for socio-economic growth to achieve sustainable development in the bottom of the pyramid settings. However, research evidence on sustainable leadership in the CBSE context from theoretical perspectives in practice is limited to date [34]. More importantly, the assessment of sustainability leadership in this sector is relatively undeveloped, especially in emerging economies, such as Thailand.

Overall, the topic of sustainability or sustainable leadership has been theoretically developed over the last decades. Yet, how the theories work in practice, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic crisis, has not yet been studied, with limited evidence. Hence, this sets a focal theme of this paper and becomes a critical inquiry. Therefore, the key research questions are as follows:

- (1)

- What are the essential sustainable leadership practices and sustainability competencies for sustainability and resilience in a CBSE context?

- (2)

- How can a CBSE business apply the theoretical frameworks in practice to survive and thrive for sustainable futures, especially during the COVID-19 era?

In sum, our paper aims to contribute to the currently limited scholarly knowledge and advance the theoretical development in this emerging field within the SME sector, particularly in the scarce research context of CBSE in a fast-developing country such as Thailand. Next, we will critically review the relevant literature and elaborate on the SL theoretical framework and research methodology used in the study. Lastly, we will discuss the findings and provide insightful, conclusive implications with suggested limitations and future research.

2. Literature Review and Research Framework

2.1. Critical Review of the Literature

The topic of sustainability or sustainable development originated in the World Commission on Economic Development (WCED), or the Brundtland Report, over 30 years ago [35]. Since September 2015, the United Nations has set a 2030 agenda for sustainable development or Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). These global goals cover three pillars of sustainability, specifically, people (social goals), prosperity (economic goals), planet (environmental goals) dimensions, along with peace and partnership, with the aim to create a better world for future generations [36]. Our world still faces diverse sustainability problems, e.g., climate change, environmental hazards, poverty, inequalities and political instability. In fact, these sustainability challenges require leadership and strategic foresight from multi-lateral parities and stakeholder orientation to take corrective and transformative actions toward balancing social-economic and ecological development [6,37,38]. Furthermore, the literature suggests that relevant value-based competencies, including strategic (management) competence, systems thinking competence, anticipatory (foresight thinking) competence, interpersonal competence and ethical competence, are needed to support the development of sustainability leadership and sustainable entrepreneurship in business, as suggested by the foregoing literature [8,9,10,11]. Further, firms need to incorporate societal and environmental responsibility while meeting the needs of all stakeholders and future generations [39,40]. Hence, sustainability leadership has strategically become critical to achieve sustainable goals and futures.

In the literature, the sustainability interests in the leadership field have increasingly grown in recent times. Diverse strategic leadership approaches for business sustainability have been proposed in the past three decades. Previous research [12,13] summarizes the differences and similarities. For instance, “stakeholder-based leadership”, with the focus on stakeholder relationships and triple-bottom-line criteria [22,41,42,43], “ethical leadership”, with emphasis on ethical business standards [44,45,46], “sufficiency leadership”, with the focus on a more ecological-economic-societal balancing approach toward sustainable development [47,48,49] and “sustainable leadership”, centered around the multidimensional nature of leadership behaviors and management systems to create long-term business sustainability and resilience [7,12,19,24,50].

A recent bibliometric review of sustainable leadership from worldwide scholarship by Halliger & Suriyankietkaew indicates the rapid development of new theoretical models of leadership and sustainability over the past few decades. The existing trend highlights the theoretical development of six schools of thought, comprising “sustainable Leadership”, “leadership for corporate sustainability”, “managerial leadership”, “responsible leadership”, “ethical and transformational leadership” and “leadership for sustainable change” [5]. They relate to how leadership contributes to sustainability in organizations and societies. The prominent ones are referred to as “sustainability leadership” [2,51,52,53], or, alternatively, “sustainable leadership” [3,7,12,13,19,24,50,54,55,56,57]. These theoretical notions are used interchangeably for parsimony and clarity. The review also reinforces the growing major trend of the theoretical advancement of sustainable leadership, with a balanced view of sustainability values towards sustainable futures [5]. In this paper, we thus undertake sustainable leadership as the integrative theoretical leadership framework for corporate resilience and sustainability.

2.2. Sustainable Leadership Research Framework

Sustainability leadership is a process of influence that delivers direction, alignment and commitment and aims to address environmental, social and long-term sustainable development [58,59,60]. Various terms in the literature such as “green leadership”, “eco-sensitive leadership”, “sustainability leadership” and “globally responsible leadership” are used interchangeably and convey the same concept of sustainable leadership [59,60,61]. In this paper, we primarily use the term sustainable leadership (SL). SL comprises those behaviors and practices that create lasting value for all stakeholders, such as the society, environment and future generations at large [7,19].

Built on the Rhineland capitalism approach [62], Avery first introduced 19 SL practices. The 19 practices were derived from a study of 28 global corporations, in which 13 were European corporations (Germany and Switzerland) and the remaining 15 corporations stemmed from developed economies (Australia, Hong Kong, Japan, South Africa and the USA) [54]. Later, Avery & Bergsteiner expanded the list of practices and identified 4 additional practices to generate a set of 23 sustainable leadership practices or “Honeybee” leadership approaches in 2010 [7]. The four additional practices added in the latest sustainable leadership are trust, innovation, staff engagement and self-management.

The 23 practices are interdependent and reinforce one another within the levels [7]. The 23 practices are categorized as foundation, higher-level and key performance drivers. The outcomes of the Honeybee leadership model, which Avery & Bergsteiner introduced, go beyond the triple bottom line, with results that enhance brands, customer satisfaction and long and short-term financial viability while providing long-term value for all stakeholders. Avery & Bergsteiner arranged the 23 leadership practices into three structural levels of SL practices as follows. Firstly, the foundation practices consist of 14 practices including developing people, labor relations, retaining staff, succession planning, valuing staff, CEO and top team, ethical behavior, long-term perspective, organizational change, financial markets orientation, environmental responsibility, corporate social responsibility (CSR), stakeholders and the vision’s role in the business. Secondly, higher-level practices have been developed based on the idea that when foundation practices are in place, they facilitate and support the initiation of higher-level practices. The six practices include consensual and devolved decision making, creating self-managing employees, team orientation, cultivating a trusting atmosphere, forming an organizational culture that enables sustainable leadership and sharing and retaining the organization’s knowledge. Thirdly, SL indicates that three key performance drivers, namely, innovation, staff engagement and quality, can drive organizational performance.

A synthesis of the previous bibliometric review also reveals several common features that conform to the theoretical SL framework. They include emphasis on leadership as a management system, a long-term vision with broader goals that link organizations to society, ethical behavior, corporate social-environmental responsibilities, innovation capacity, systemic change and stakeholder orientation [5]. These values underlie both the vision that leaders and stakeholders strive to achieve through corporate sustainability and the resilience.

Research indicates that firms adopting the SL principles create sustainable performance outcomes and resilience in the long run. Empirical research also suggests that the 23 SL practices are significantly associated with diverse organizational outcomes, such as financial performance [12,24], customer satisfaction [50] and stakeholder satisfaction [57]. Yet, most studies were conducted in developed countries [7,19], and previous case studies mostly examine the SL practices in large or listed corporations [63,64]. More evidence-based case studies are needed in future research [65]. Responding to the literature call for further theoretical advancement in this emerging field, this paper adopts SL to investigate how the SL theoretical framework can be applied in practice, specifically in the context of community-based social enterprises.

2.3. The Concept of Community-Based Social Enterprise (CBSE)

The introduction of the “Social Business” concept by the 2006 Nobel Prize winner Muhammad Yunus through his work on social microfinance in poverty alleviation was a conceptual starting point for social enterprises. The topic of social enterprise (SE) has gained global significance and has attracted worldwide attention from academic researchers, practitioners and policymakers [26]. SE is defined as the businesses or organizations that primarily focus on delivering social or environmental benefits in a self-sustaining way [27]. It has been regarded as a more sustainable approach compared to a non-profit organization, which mainly relies on philanthropic charities and donations [66]. It can fill the gap that the public or private sector cannot provide. Therefore, it is essential for economic growth and advances sustainable development.

Community-based social enterprise (CBSE) is a typical form of social enterprise. CBSEs are non-profit, independent organizations with a solid geographical characteristic that earns income from community-owned-and-operated activities as well as contributes to the local development and well-being of communities [29,30,31,32]. It differs from other social enterprise concepts due to the following two unique attributes: (1) its solid local engagement from community members through a self-managed, community-driven governance structure in the development of an organization’s direction or objectives, and (2) its multifunctional organizations with strategic decisions that focus on local priorities [29].

Several terms have similar meanings to CBSE but appear in various research disciplines. They are “community enterprise” [32,67,68], “community-led social enterprise” [69,70] and “small and micro community enterprise” [71,72]. All these terms are interchangeable. Table 1 presents various CBSE definitions. They show some commonalities. First, in the CBSE context, locals take ownership of the enterprise and community development. Second, planning and management processes should be done by locals. Third, the enterprise generates economic, social and ecological benefits to support the community. In this paper, we adopt the CBSE definition by Somerville & McElwee since it explains and integrates all the critical multi-dimensional aspects of CBSE [32]. In this study, CBSE refers to a subset of social enterprise that is an independent, not-for-private-profit organization, which is owned and managed by highly committed community members, with an aim to create long-term benefits to the local people for sustainable development.

Table 1.

Definitions of Community Based Social Enterprise (CBSE).

Our literature review suggests that CBSE has five essential characteristics [29,30,31,32]. First, it is community-owned, by which assets belong to a community and cannot be sold for personal gains. Second, it must be operated and managed by community members. Third, the profits from the enterprise are shared among members or re-invested in the community business. Fourth, it aims to solve the social and environmental problems whilst delivering long term benefits to the community. Lastly, it is financially self-sustaining or minimizes the dependence from government funding, grants and donations.

While each CBSE case may vary based on their distinctive contexts, the literature identifies several underlying common success factors in the development of CBSE. These include leadership [28,33,79], local ownership [31], community participation and partnership support from within and outside the community [80,81,82], plus benefit-sharing [83,84]. In fact, CBSE represents a transformational change from traditional top-down to bottom-up participatory leadership approaches, and an absence of necessary leadership support may adversely affect CBSE progression toward sustainability [85]. Importantly, the literature puts the emphasis on leadership as the key driver to help CBSE recognize opportunities and risks and mobilize capital and capacities to achieve social benefits [33]. Hence, our study focuses on examining how the theoretical sustainable leadership practices are pragmatically implemented in the underdeveloped CBSE context.

2.4. Integration of Sustainable Leadership (SL) and Community-Based Social Enterprise (CBSE)

This paper intends to advance the currently limited research regarding SL in the CBSE context. How the theoretical framework of SL is relevant to and may be integrated into the CBSE context can be explained in Table 2. Table 2 provides functional descriptions of how these sustainable practices fit into the CBSE context. Each leadership element addresses issues and challenges that CBSE leaders may face when implementing the practices to achieve sustainability and resilience.

Table 2.

Integrative relevance of SL and CBSE.

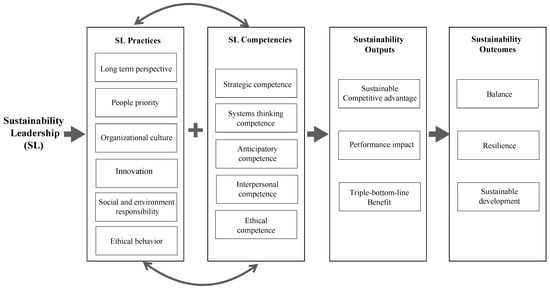

In addition, this paper responds to a call for more evidence-based case studies to advance the SL theoretical research in the CBSE context. To answer the research inquiry, the study examines the 23 sustainable practices built by Rhineland’s previous sustainability leadership research framework [63,65]. The SL practices are thus grouped into six categories: long-term perspective, people priority, organizational culture, innovation, social and environmental responsibility and ethics [63]. Additionally, we further examine other relevant value-based sustainability leadership competencies, including strategic (management) competence, systems thinking competence, anticipatory (foresight thinking) competence, interpersonal competence and ethical competence [8,9,10,11], to advance the theoretical development of SL in business.

2.4.1. Long-Term Perspective

The literature indicates that organizations should consider long-term perspectives rather than short-term views for sustainable growth [86]. Hofstede & Minkov’s cultural study also indicates that long-term orientation is prominent in Asian cultures and becomes crucial for the economic development [87]. Research indicates that a sustainable enterprise must focus on the long term over the short term to achieve sustainability and resilience [7,19,88]. Leaders and members with the long-term orientation tend to emphasize the long-term future actions and outcomes, including thinking, planning decisions and strategies, instead of the short-term goals [63]. Built on the previous studies, the long-term orientation also requires diverse sustainability leadership competencies, namely, strategic (management) competence, systems thinking competence and anticipatory (foresight thinking) competence [8,9,10,11]. These sustainability leadership competencies incorporate the ability to think strategically and systematically in order to analyze complex systems toward sustainability strategies and future transformation. The competencies also help anticipate potential consequences for future sustainability issues and decisions made by the enterprise at present.

Apart from its long-term thinking and management orientation, building long-term stakeholder relationships with related stakeholders (i.e., suppliers, customers, employees and the community) helps enhance future business wellbeing and the prosperity of SMEs [24]. The word “sustainability” clearly implies the long-term span over time. In the CBSE context, community leaders and their members are held accountable for their decisions and actions that affect related stakeholders in both the short and long term [89]. Every decision-maker must consider long-term impacts. The long-term orientation can improve the CBSE sustainability when all stakeholders are satisfied and a compromise between short- and long-term goals in all prudent decision-making are prudentially considered [12,54,56]. Long-term orientation allows organizations to outperform their competitors with the short-term thinking [90]. Recent studies [12,24,56,91] indicate that companies with long-term thinking and investments outperform their counterparties.

In light of the literature, the long-term orientation is a critical practice to create sustainable impacts in CBSEs. Hence, this study intends to investigate this SL element and the related competencies to advance the scanty research. It also seeks to understand how these values and practices can support the socio-economic and ecological development of a real-life CBSE setting, particularly during the COVID-19 era.

2.4.2. People Priority

People are core to organizational sustainability, and human capital is essential to socio-economic development [88]. Continuous people development or human resource development (HRD) is fundamental to human capital through various forms of education and skills trainings [7,19]. In practice, human resource management (HRM), comprising positive relationships with laborers, valuing people, staff retention and succession planning, is key to creating sustainable well-being and success in businesses, consistent with the literature [7,19] and sustainable HRM research [92]. The literature also stresses the importance of people priority and long-term staff retention within the community to create sustainable enterprises [65].

Importantly, people priority also extends to care for stakeholder orientation. Leaders care for all employees and stakeholders in sustainable firms [12,56]. Sustainability leadership works toward establishing good stakeholder relationships and partnerships with both internal and external stakeholders (e.g., staff, customers, suppliers, locals, academics, NGOs and governments) [22,24,53]. Stakeholder engagement and capacity building are imperative for sustainable leadership [5]. From a strategic management for sustainability perspective, stakeholder management and partnerships become vital for sustainable development [6]. A SME study also reveals that caring for stakeholders is a significantly positive driver for enhanced long-term financial performance [12,56].

Furthermore, the literature puts forward the importance of building sustainability leadership capabilities, particularly strategic (management) competence, systems thinking competence, anticipatory (foresight thinking) competence, interpersonal competence and ethical competence. [8,9,10,11]. These competencies strategically and systematically enhance people engagement, stakeholder interdependence and organizational ethical values, which can help transform future sustainability leadership and enterprises.

Previous research suggests that a sustainable CBSE should value and care for the people, including the community members, the locals and other stakeholders. The key purpose is to improve their well-being and support progressive socio-economic development in the CBSE. Hence, our research hopes to study this SL element and relevant competencies to advance our currently limited knowledge in this sphere in the CBSE context.

2.4.3. Organizational Culture

Sustainable leadership theory puts emphasis on building a strong organizational culture. Scholars signify that a shared, strong culture and values drive longevity, resilience and long-term corporate success [12,56]. Underlying values and beliefs in a culture suggest how people should behave and help employees identify desirable behaviors. Collins & Porras’s (1996) study shows that “built-to-last” companies shared strong cultures with their people, which make them the “special place to work” [93]. Empirical research also suggests that a strong and shared culture is a significant predictor of employee satisfaction [50]. The recent literature suggests that sustainability leaders should strategically and systematically enable people to develop “personal connection” and “empowerment to act” to achieve sustainability in business [8]. Despite the strategic and systemic thinking competence, the organizational culture also requires interpersonal and ethical competence to build sustainability leadership and organizations [10,11].

Based on the SL theory, sustainable enterprises foster a strong organizational culture with a shared vision. Culture is often managed through statements of vision, values and/or philosophy, statements intended to express direction, core beliefs and informal guidelines to influence the behavior of organizational members [64]. A vision is defined as a psychological image of the desired future for a community [94]. A meaningful and powerful vision can empower organization members’ sense of ownership, emotional commitment, engagement and accountability toward sustainable goals [95,96]. Empirical research also supports the idea that the strong and shared vision can positively drive long-term financial performance [50]. In total, sharing a strong vision with employees is vital to create sustainable enterprises [12,56,63].

From the preceding discussion, it is expected that a strong culture with vision-sharing among all organizational members is key to sustainable enterprises. This study thus hopes to explore the SL element and the associated competencies to advance the SL theory as well as explain how a CBSE business may apply the theory to create sustainability and resilience.

2.4.4. Innovation

Sustainability leaders must rely on innovation to build successful enterprises. Rhineland’s sustainable enterprises use innovation as a critical competitive advantage to lead their respective markets [54]. Continuing innovative organizations can lead to long-term growth and sustainable results [12,56,90]. Sustainable enterprises rely heavily on innovation in teams where shared leadership and collaboration among members are presented [7,97]. The research states that SMEs need to cultivate an empowered culture to create innovation capability [98]. Innovation and trusting team members are important for SMEs [99], and small enterprises should rely on their teams’ abilities to be innovative and achieve competitive advantages [100]. In recent research, a trusting, innovative team is a significantly positive driver for enhanced sustainability performance outcomes, particularly long-term financial performance and stakeholder satisfaction, in the SME and entrepreneurial contexts [12,13]. In total, innovation is key to sustainable firms and socio-economic development. Researchers also indicate that social innovation can drive long-term success and sustainability in small community enterprises [101,102].

The literature also highlights that building sustainability leadership with innovation requires diverse competencies. They are the strategic management, systems thinking, anticipatory and ethical competencies. The sustainability leaders are required to think strategically and manage their innovation initiatives in anticipation of future sustainability needs and ethical-oriented values to achieve a balancing socio-economic and environmental responsibility [8,10,11].

Furthermore, the recent literature indicates that social innovation enhances sustainable development in community enterprises [103]. Social innovation is referred to as a “distinctive and effective response to address unmet needs motivated by a social purpose which enhances social assets and capabilities” [104] (p. 471). The social innovation can be developed or grown from their traditional cultural and/or rich environmental heritage [105]. Community members normally decide on initiatives and solutions that are best for them by their own without external pressure. Collectively, the community members try to solve a particular issue or problem by innovating positive solutions that are expected to happen and processing through their collective group innovation [106].

Existing research in the area of sustainability-oriented innovation in the CBSE context in this area is still underdeveloped. This paper thus intends to explore the lacking topic of how a CBSE business can embrace or enable continuing and social innovation to support community development and sustainability.

2.4.5. Social and Environmental Responsibility

Social and environmental responsibility is the core to develop sustainability leadership in sustainable enterprises. Sustainable businesses should positively contribute to society to grow social responsibility, preserve cultural heritage and promote ecological conservation [7]. The literature stresses the importance of anticipatory and ethical competence in thinking about how to pave sustainable paths forward with foresight as well as to enable social and environmental responsibility toward sustainable futures [8,11]. Ethical values and norms—specifically, the pro-environmental behaviors and values with a focus on strict social and environmental responsibilities—become the crucial element in a sustainable entrepreneurship model [11]. Scholars also call for the balancing of personal ethical values and business objectives when planning and implementing social-and-environmental responsibility activities [10].

The sustainability leaders often go beyond what the law and society require in their social and environmental responsibilities. Being socially and environmentally responsible pays off by increasing sustainability performance outcomes [65]. Social responsibility is also found to be the significant key predictor of long-term financial performance in SMEs [24]. Researchers show that sustainable enterprises that operate businesses beyond minimum regulatory requirements with sustainability orientation can outperform those without [65,107]. SME firms with care for socio-economic and environmental focus can enhance profitability and competitive gains [99,108]. Recent studies also affirm an upcoming trend towards a green ideology and socio-environmental sustainability [109,110].

According to the SL theory, sustainable enterprises are primarily concerned about social and environmental responsibilities. In the CBSE context, enterprises do not solely focus on generating economic benefits but also gear toward social and ecological benefits to support the community [29]. Therefore, our study intends to examine the SL element in practice and how a CBSE business can survive and thrive for sustainability and resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic crisis.

2.4.6. Ethical Behavior

Ethical values and behaviors are essential for sustainability leadership to build sustainable firms. Leadership principles should stem from ethics and moral principles as the foundation for business sustainability [49,111]. A moral purpose and ethics must be embedded in enterprises to create corporate sustainability [112]. Ethics help create positive organizational impacts (e.g., integrity, loyalty and fairness at work) as well as promote equitable and virtuous environments with justice, equality and human rights [113,114]. Scholars [115,116] highlight that enterprises need to support ethical leadership to foster a strong ethical culture and create corporate values that drive sustainable performance outcomes. In the literature, ethical enterprises are found to enhance employee satisfaction, a superior business performance competitive advantage [49,57,112]. A meta-analysis indicates that leadership and ethics should go hand in hand as the strategic elements to support organizational strategies and drive the balancing of socio-ecological and economic values for long-term sustainability [4].

Diverse researchers also put forward the significance of ethical competence with moral values in developing sustainability leadership in business [8,11,117]. Osagie et al. suggest that sustainability leaders should apply personal ethics to a business situation, called “personal value-driven competencies”, in order “to strike an appropriate balance between idealism and pragmatism” [10]. The literature also highlights the magnitude of motivation or “the moral transformation from a passive attitude with respect to sustainability issues into an active and engaged attitude” [10]. Furthermore, pro-environmental behaviors and values with a strict focus on social and environmental responsibilities are key to developing sustainability leadership in business [8,11]. As a result, ethics become critical for creating a sustainable entrepreneurship model [11].

According to the literature, ethics are key to corporate sustainability and resilience. Yet, evidence-based research that investigates ethics and sustainability in the CBSE setting is still lacking. Therefore, this research aims to study this SL element and the associated competencies to advance the SL theory in this sphere as well as to explore how these ethical and moral values are operated to develop sustainability leadership and build a sustainable CBSE.

2.5. Community-Based Social Enterprise (CBSE) in Thailand

Historically, the concept of social enterprises has a long history in Thailand stretching back over a century ago. It originated from a cooperative form of business, called a “co-op” for short, by low-income farmer communities in rural areas to expand markets and gain financial access [118]. The government of Thailand has recognized the social enterprise model as an alternative means for promoting community development and driving sustainable socio-economic growth. In May 2009, the Social Enterprise Promotion Act was launched to promote, register and provide grants and loans for registered social enterprises [119], and the Social Enterprise Thailand Association or SE Thailand was established with aims to build a network among social enterprises and work collaboratively with other sectors to boost social and environmental impacts [120,121]. According to the Social Enterprise Promotion Act 2019, social enterprises that want to register with the Office of Social Enterprise Promotion (OSEP) must meet the following criteria: (1) have a clear social purpose and good governance, (2) generate at least 50% of revenue from selling community-based products or services and (3) reinvest at least 70% of profit into social purposes. The registered social enterprises benefit from tax allowance, and their sponsors are also eligible for a tax reduction. As of February 2021, there were 148 registered social enterprises under the new Act [121,122].

Expanding from the traditional view of social enterprises, the concept of community-based social enterprise (CBSE) in Thailand is increasingly recognized as a sustainable solution for socio-economic development at the community level and in the bottom of the pyramid setting. Since 2001, the Thai government has developed One Tambon One Product (OTOP) as a project initiative to promote the CBSE concept to the public. According to the Community Development Department (CDD), Ministry of Interior, the initiative intends to create one community-based product or service per municipality to support poverty alleviation and increase prosperity in every Thai village [123]. The government provides funding, technical assistance, business consultancies and market access to both domestic and international markets. Yet, the local communities have their rights and accountability on every business decision, ranging from product development and marketing to sales. In fact, OTOP is regarded as an instrument to build up social entrepreneurial activities among the grassroots. The government introduced a grant of one million Baht to fund the project accordingly and allocated its budget to 74,989 villages during the third phase of its project implementation [123,124].

Later in 2005, the Community Enterprise Promotion Act was enacted with an aim of supporting and promoting CBSEs in Thailand. Later, this act evolved to the Unity Civil Society Policy or “Pracharat Rak Samakki” in 2015 [124]. Then, the Department of Agricultural Extension, Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperative oversees registration and administrative support for the community enterprises. Thus far, there are 116,298 registered community enterprises, but only 520 of them were officially registered as legal entities or companies as of 2021 [121,125].

According to Sakolnakan & Naipinit [126], there are three levels of community enterprises in Thailand.

- Primary Level. At this level, the community enterprises produce their own goods for their own consumption on a small scale, such as consumables such as soap, shampoo and dishwashing liquid, and the produced goods can be locally sold to community members at lower prices than those of large manufacturers. This can help lessen the cost of living for people in the community.

- Development level. Community enterprises at the development level have the capacity to develop their new market channels. Additional goods and services are primarily sold to neighboring communities and other people who visit the communities. The revenues and profits from those transactions return to their community.

- Progressive Level. At the progressive level, community enterprises produce their goods and services for mass markets. They better understand the market mechanism and continuously expand to other external markets and the general public. Profits are used to grow their businesses for community development and sustainability.

In addition, the literature identifies many challenges and obstacles found in CBSEs in Thailand that hinder their business success. For example, poor leadership and organizational management, limited production capabilities because of old machinery and the high cost of labor [127], accounting and financial management [128,129] and marketing and product development in terms of product design, trademark, labeling, packaging, pricing and proper distribution channels [130,131,132]. Since the literature highlights the importance of CBSEs in sustainable development, this paper intends to expand the underdeveloped SL theoretical knowledge and its application for sustainability and resilience.

3. Business Case: A Community-Based Social Enterprise of Tung Yee Peng Village

This paper mainly focuses on the business case of a CBSE context in order to advance our knowledge in the limited field. For the investigation, the CBSE case study is called Tung Yee Peng Village (TYP), located in a Koh Lanta Island in the Krabi province of Thailand. Koh Lanta Island is a famous international tourist attraction with beautiful white sandy beaches, rocky shores, colorful coral reefs and rich natural resources from marine biodiversity. TYP is a small coastal fishing village surrounded by abundant nature with mountain forests, sea mangroves and rivers, with a total geographic area of 5.6 square kilometers. It largely is home to a Muslim community that has been settled for more than 100 years with a love of the nature and its strong cultural heritage [133]. In 2004, the TYP community survived the tsunami disaster due to its abundant mangrove forest, which has been registered as a community forest. After the tsunami hit in 2005, the community received support from the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) to build a pier bridge to connect the mainland and the island, which could lead to a community forest learning center. Currently, the population is about 1065 people with 300 households.

Due to its popular tourism destination of Koh Lanta, TYP has developed as a famous community-based tourism spot on the beautiful island. The ecotourism activities have attracted many outsiders, investors and tourists into the area. In 2011, TYP was officially registered as an Ecotourism Community Enterprise Group, with an original local membership of 130. This CBSE has been led by the strong visionary leadership of Mr. Narathorn Hongthong for over eight years. His leadership has supported the community toward organic growth, in which the locals own and operate all activities at the CBSE. The community members have a strong participative engagement and commitment regarding how to capitalize natural resources and cultural heritage sustainably. This CBSE has focused on three main areas of development: (1) community-based tourism, (2) community forest management and (3) the promotion of sports in the community. To balance the socio-economic and ecological responsibilities, this CBSE offers ancient gondola sailing and kayaking in its serene mangrove forest to enjoy the beautiful island with rich biodiversity. The tourism program also includes its famous “Dawn bathing program” and “Moonlight bathing program” with their morning and night gondola rides. The social enterprise also provides local homestay services, called the “home plus” initiative, which let tourists experience the traditional local foods and community lifestyles. It also expands to sell the community homemade and handmade products, such as shrimp paste, dried fish, herbal tea and shrimp oil. The TYP community-based social enterprise has equitable benefit-sharing among the local community members.

Furthermore, to serve the increasing demand of tourists, the village also expands its networks to partner with other local entrepreneurs, such as luxury hotels and resorts, car rentals, boat rentals and souvenir shops, to help tourism at ease, and TYP has also created diverse multi-lateral partnerships with external parties, such as the Royal Forest Department, Krabi Community Development Office, Tourism Authority of Thailand–Krabi office, Office of Tourism and Sports and several higher education institutes, to support community exchanges of ideas and knowledge-sharing.

Indeed, the TYP village is a successful community-based tourism model. It has received many awards over the years. In 2017, it received the Best Community Forest Award. In 2020, it won the Best Rural Tourism Award in the category of Best Responsible Tourism, organized by the Tourism Authority of Thailand [134]. Today, TYP is a self-sustaining community business, as it has grown to become a progressive-level CBSE according to Sakolnakan & Naipinit [126].

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the local community enjoyed the economic growth. Yet, the tourism has, to some extent, caused geosocial changes in the traditional fishing and farming cultures, and the people have turned and engaged in the tourism service businesses. The changes have raised many concerns for some community members, who want to maintain a simple lifestyle and live in harmony with nature. The rapid growth of tourism businesses has raised critical questions about environmental conservation and cultural heritage preservation for the community. However, the pandemic crisis has hit this CBSE like many other businesses. Hence, this paper aspires to study the sustainability leadership in practice, particularly in the underdeveloped CBSE context.

4. Research Methodology

The study employs a qualitative case study research design to answer our research inquiries. The theoretical sustainability-oriented leadership research frameworks are mainly based on Avery & Bergsteiner’s 23 sustainable leadership [7] and sustainability competencies [8,9,10,11] to examine our key research questions and further advance the SL theory. In particular, our business case study focuses on the green or ecotourism community-based social enterprise (CBSE) of Tung Yee Peng (TYP) village, as discussed in the previous section. Importantly, the evidence-based research was conducted according to the international ethical standards and approved by the Mahidol University Central Institutional Review Board (MUCIRB).

We adopted a multi-data collection method to collect data to answer the research questions with a multi-stakeholder perspective. We employed in-depth interviews, non-participant observations and references to the documentation and information supplied by or published about the enterprise to enhance the quality of the research, as suggested by Yin [135]. Our data collection was aimed to gain better knowledge about the CBSE development and its community members’ perceptions, satisfactions, challenges and opportunities at the CBSE pre-COVID-19 and during the pandemic, along with their opinions regarding its economic, social and environmental impacts on sustainability and resilience. Due to the varying COVID-19 pandemic situations in 2021, we conducted our data collection in both on-line and on-site modes. We collected primary data from several semi-structured in-depth interviews, focus groups and non-participatory observations of the diverse stakeholders at the TYP village. We also interviewed the leader or head of the community and social enterprise, its CBSE committee members, its community residents, the nearby locals and business entrepreneurs in the surrounding areas. Moreover, we conducted in-depth interviews and focus groups with its related external stakeholders, including the three-panel judges of the Thailand Rural Tourism Award 2020, the chairman of the Lanta Island Tourism Association and its visiting tourists. In total, we collected data from several face-to-face interviews and focus groups with more than 30 voluntary participants at the CBSE site.

In general, in-depth interviews and focus groups provide the researchers the benefit of exploring a given topic and gaining insight. The in-depth interviews allow for the exploration of the personal thoughts, attitudes, perceptions and behaviors of the interviewees in a safe environment without peer judgement [136]. Focus groups can help generate data based on the synergy of the group interaction [137]. We also engaged in participative and non-participative observations at the CBSE sites. The observations help the research team to gain better understating of the context [138]. Regarding the technical approach, all participants were informed of the study objectives. In addition, note-taking and tape- recording techniques were also employed during the interviews [139]. The open-ended and probing technique was used during the in-depth interviews to generate qualitative data [139]. The probing questions allowed the researcher to clarify contents and document analysis explored in the in-depth interview answers [140]. In addition, our secondary data were derived from publicly available publications, such as newspapers and publicized media from reliable sources and institutes.

For data analysis, thematic analysis [141] was employed to organize the data, identify commonalities and offer insight into patterns of meaning (themes) across the data set. The literature indicates that it is a form of pattern recognition within the data, where emerging themes become the categories for analysis [142]. The analysis also supported the researchers in conducting the mechanics of coding and analyzing the qualitative data systematically so that it could later be linked to broader theoretical or conceptual issues/themes, as advocated by the literature [141]. According to Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, the thematic analysis demonstrates a combination of inductive and deductive thematic approaches [142]. The methodological approach thus helped us to integrate data-driven codes with theory-driven ones.

In this study, the thematic analytical approach allowed the researchers to independently examine and make sense of collective or shared meanings and experiences from the empirical data and observations for conclusive patterns or thematic identification. Further, it helped us to provide deductive reasoning for testing the theories. In practice, we examined to what extent TYP’s practices are congruent with the sustainable leadership principles by investigating the theoretical SL conformity levels. The assessment levels can be classified on a range from “least evident”, to “moderately evident”, to “most evident” based on the relative strengths of the evidence found in the case study, as illustrated in the next section. In addition, we studied how the community-based social enterprise could pragmatically employ the sustainability leadership competencies, based on the identified categories, through the theoretical mapping and interconnection. Largely, the data analysis helped us to uncover both descriptive insights about the sustainable practices in the real-life CBSE context and enhance the SL theoretical advancement.

Furthermore, document analysis [143] through reviews of the company-related documentation or publications from the secondary data was employed to explore the data, elicit meaning and gain more in-depth understanding about the CBSE context. More importantly, we also ensured the validity and reliability of the qualitative study using triangulation [144]. We triangulated using multiple sources of evidence and the aforementioned combined analysis and approach for comprehensive analysis, understanding of phenomena and theoretical development, as suggested by the literature.

In conclusion, the qualitative case study method and techniques were specifically employed to answer the research inquiries with three main goals: (1) to validate the data for the rigor and quality of the research, (2) to gain insights into the phenomena of the specific context in this case study and (3) to present the robust evidence and reliable findings for further theoretical advancement. Overall, the described research method in this study helped us to expand our limited understanding and scholarly knowledge about the SL theoretical development of the CBSE phenomenon as well as provided us with vigorous evidence on how the sustainability leadership theory could be practiced in an actual setting with validity and reliability.

5. Analytical Findings

The following analytical findings intend to address our key research inquiries. The beginning part answers the first research question: what are essential sustainable leadership practices and sustainability competencies for corporate sustainability and resilience in a CBSE context? Our analytical findings employ both theoretical frameworks (i.e., the sustainable leadership and the sustainability competencies), which are separately analyzed and discussed in the resulting subsections. Further, the later part responds to the second research question: how can a CBSE business apply the practices and competencies in action to survive and thrive for sustainable futures, especially during the COVID-19 era? In particular, the research context focuses on the green or ecotourism CBSE of the Tung Yee Peng (TYP) village during the COVID-19 era, as described in turn.

Using the theoretical SL framework, we can identify varied extents of the conformity of the CBSE with diverse sustainable practices and sustainability competencies. Built on the previous SL study in a community business, the SL conformity levels are based on the relative strengths of evidence found in the case study [65]. The levels can be classified on a range from “least evident”, to “moderately evident”, to “most evident”. We can also group the 23 SL elements based on Avery & Bergsteiner’s theoretical framework into six relevant categories, as previously elaborated in the integration of SL and CBSE (see Table 1 and Section 2.4) [7]. The assessment of sustainable leadership in the CBSE of Tung Yee Peng is elaborated next.

From the analysis, the CBSE in TYP appears to be broadly conform to the SL research framework. Table 3 presents a summary of the resulting findings. From Table 3, we can identify all 23 sustainable leadership practices at the CBSE setting, but to different degrees. The evidence suggests varied conformity with the SL theoretical framework. The sustainable practices are not mutually exclusive but are interrelated to enhance corporate sustainability. In this study, we can distinguish six SL relevant categories, as supported by the literature. They cover several interconnected sustainable leadership practices, as presented in sequence.

Table 3.

Sustainable leadership grid at the Tung Yee Peng community-based social enterprise.

Firstly, the TYP community-based social enterprise strongly adopts a long-term perspective, which covers 17 out of the 23 SL practices including managing and developing people, long-term planning, high quality and organization-wide management practices. Secondly, the evidence suggests that 17 out of the 23 SL elements are well associated with people priority, including varied HR perspectives from HRM to HRD, stakeholder orientation, teamwork and staff engagement. Thirdly, 19 out of the 23 SL aspects are greatly linked with the organization culture to enable its employees, support the strong culture and enhance its all-inclusive organizational management systems. Finally, nine out of 23 SL components are found under the innovation category, comprising organizational change, knowledge-sharing and retention and quality. In terms of social and environmental responsibility, 7 out of the 23 sustainable practices, specifically, social responsibility, environmental care, stakeholder orientation and quality, are integrated in the social enterprise. Lastly, 14 out of the 23 SL elements are clearly connected to the ethical behavior category, such as valuing staff, high quality and embedded ethical conducts in all business decision-making and management activities, as illustrated in Table 3.

In addition, our subsequent analysis addresses the following question: what are the essential sustainability competencies for corporate sustainability and resilience in a CBSE context? Stemming from the theoretical framework for sustainability competencies [8,9,10,11], we particularly identify five critical sustainability competencies for corporate sustainability and resilience in a CBSE context. They are strategic (management) competence, systems thinking competence, anticipatory (foresight thinking) competence, interpersonal competence and ethical competence. These competencies are crucial for developing sustainability leadership, as supported by the preceding literature.

To advance the theoretical development of the SL theory, we integrate the theoretical SL practices and sustainability leadership competencies in a single study. Our integrative SL theoretical framework for sustainability practices and competencies is shown in Table 4. It generally depicts the integration of the theoretical SL practices and sustainability leadership competencies as they are applied in practice, based on the evidence found at the Tung Yee Peng community-based social enterprise.

Table 4.

SL practices and competencies grid at the Tung Yee Peng community-based social enterprise.

Table 4 also illustrates the importance of the leadership competencies that are required in developing sustainability leadership along with the SL categories, based on the evidence found in practice. The evidence suggests that the leadership competencies are not mutually exclusive but are interrelated to enhance each of the sustainable leadership categories.

The next part subsequently responds to the second research inquiry. The following analytical findings demonstrate how the community-based social enterprise can pragmatically apply the value-based sustainable leadership practices and sustainability leadership competencies in practice. In brief, the results entail how the CBSE business can put various sustainability leadership practices and sustainability leadership competencies into action, as elaborated in sequence.

5.1. Long-Term Perspective

One finding reveals that the social enterprise adopts a strong long-term orientation consistent with the abovementioned literature. At TYP, its mission focuses on long-term inclusive sustainable growth for all. According to the Head of the TYP community-based social enterprise, the mission states: “developing the economy, society, and environment at the family level”. This mission involves both internal and external stakeholders. Going beyond short-term profits, the social enterprise exhibits that every decision or practice it makes must create lasting values for all stakeholders and benefit the society and future generations. It also suggests the necessary sustainability leadership competencies, specifically, the strategic and systematic thinking and anticipatory capacity. These essential competencies are integrated in its sustainability-oriented strategy toward creating shared values and sustainable futures, aligned with the literature [8,9,10,11]. Our analytical results from diverse interviews also show the following evidence that the long-term orientation is key to its sustainable development.

“We want to avoid the short-term capitalism concept. We pay attention not only [to] revenue from tourism but also [to] the impact on the environment and livelihood of people in the community. We need to have a long-term plan.”—Head of the TYP community-based social enterprise

“TYP is only a small village in Lanta Island. We share long heritages, challenges and hardships. We only have 300 households in the community. All of us are accountable for any actions we do, and we must think of our children and the next generations.”—TYP community-based social enterprise’s committee (A)

Taking a long-term perspective is strongly marked through its enduring cultural heritage preservation and environmental protection at TYP. Its stakeholders also observed how the social enterprise intended to create shared values within the community and for others toward sustainability.

“The community-based social enterprise has strictly complied with the stringent criteria of Global Sustainable Tourism Council (GSTC), which are the global standard for sustainable travel and tourism. The social enterprise does not only focus on its profit maximization but also preserve[s] its long cultural heritage and protect its environment as key priorities. This is why I gave the highest scores for TYP and selected it as the winner of the best responsible tourism category for Thailand’s Rural Tourism Award.”—Judge of the best responsible tourism category, Thailand Rural Tourism Award 2020 (A)

“I feel that the TYP community understands and learns how to live together with the nature in harmony. The community and locals are united toward the common goals toward good well-being of the society. The social enterprise shows us how to make the best use of its local natural resources without harming the biodiversity and ecosystem. They don’t only focus on profit but also aim to preserve the cultural heritage and community livelihood. These are my thoughts about the trip at the community.”—A tourist (B)

Our finding is also consistent with the literature finding that sustainable enterprises, which adopt a long-term perspective with moderation and sufficiency thinking, prevail and grow sustainability. During the interviews, the sufficiency mindset and resilience with long-term endurance was also presented. The tsunami catastrophe in 2005 and past crises had helped the community to focus on long-term building toward more sustainable futures, and its former careless actions, such as tree-cutting of the mangrove trees or ruining the fertile agricultural land for other fast or big money businesses like shrimp farming, had damagingly changed the ecosystems and reshaped the thinking. The adverse impacts on natural biodiversity, ecological systems and societal changes from short-term capitalism were the great lessons learned for the locals.

“We learn from our mistakes. Now, we must carefully do things and do only what we have resources and expertise for. If we have no expertise and are uncertain about investments, we will not risk investing in it. Today, we think to create long-term values more than short-term gains.”—TYP community-based social enterprise’s committee (B)

5.2. People Priority

The community-based social enterprise at TYP cares for its people as the top priority for sustainability and resilience. The social enterprise develops, values and keeps good relations with its people and stakeholders to benefit the community’s well-being and the society. The enterprise members are considered as the most crucial assets and the family, whilst other stakeholders (i.e., the locals, its community, academics and governmental institutes) are considered as its partners. Caring for its people and multiple stakeholders demonstrates its sustainability leadership capability and competencies to think and manage strategically with foresight, since these individuals have significant impacts on future sustainability and the transformation of the social enterprise, consistent with the foregoing studies [8,9,10,11]. As a result, the supporting evidence shows:

“TYP is a very small community, and we are the poorest community compared to other neighboring villages. We are more united and cohesive because of the poverty and hardship we shared. We perceive everyone as our family members. All [of the] families know each other and we are more like an extended large family in the community. We are kind to each other and help one another in everything. Regarding the community-based social enterprise we set up, we take everyone’s point of view, concern and interest into account for every decision we make. We are concerned with not only the members but also other people who are not our enterprise members.”—TYP community-based social enterprise’s committee (A)

“All villagers are like brothers and sisters. If there’s anything, we help each other out. We also have conversations to consult each other all the time.”—TYP community-based social enterprise’s member (A)

With participative leadership, the TYP social enterprise holds regular monthly team meetings with the full engagement of its committees and related stakeholders. They devolve and are involved in all of the decision-making. They commit to having a strong sense of place and ownership to enhance the community’s well-being. Moreover, they have strong accountability, with collective responsibility and emotional commitment toward the enterprise’s success. As a consequence, the enterprise members accept the shared responsibility for developing community-based tourism activities.

“There is at least a once a month meeting for the enterprise update. In this meeting, we include the government agencies, the village headman, and the assistant village headman. We get help and work together with the assistant village headman, village committees and village health volunteers. All community members fully participate in every activity, as they realize how tourism activities can positively and negatively affect their well-being.”—TYP community-based social enterprise’s committee (B)

“Altruism is one of our core values at TYP.Sometimes we have conflicts, and these misunderstandings adversely affects our enterprise’s work. Yet, when we think about our community’s benefit as a priority, all disputes are solved. And then, we are back together again.”—TYP community-based social enterprise’s committee (A)

“We feel proud of [the] TYP village. We have full ownership and shared responsibility to protect our community in preserving the long cultural heritage and conserving natural resources. We keep them for our children and the young generations.”—TYP community-based social enterprise’s member (B)

Moreover, this CBSE fosters a knowledge-sharing culture that allows everyone to share and learn from each other’s successes or failures. It also contributes as a successful community-based learning center for other neighborhoods or nearby communities. Others can learn from the CBSE’s sustainable business model, best practices or lessons learnt so that they can apply what they learn in their business contexts. However, our evidence shows that this CBSE does not have a clear succession plan or any systemic or explicit training curriculum in place, which differs from other sustainable enterprises found in the developed countries in the West. This CBSE mainly focuses on tacit knowledge-sharing and retention through community participation, meetings, discussions, story-telling and learning by doing rather than proper classroom settings or well-structured workshops. Yet, the enterprise leader has encouraged members to participate in various trainings, seminars and programs provided by government agencies and universities when opportunities arise.

“I use casual gatherings, such as having a talk over tea or meal together, rather than formal training. I show them the truth, showing what is right and not. Then, the rest of the villagers will decide for themselves. They need to think about how they would like the community and their livelihood to be.”—Head of the TYP community-based social enterprise

5.3. Organizational Culture

Sustainability leaders must cultivate a strong organizational culture to achieve sustainable success and resilience. The literature suggests that the social enterprise and its people should have a ‘personal connection’ and ‘empowerment to act’ to develop sustainability leaders in business [8]. The evidence in this case study also supports the importance of the interpersonal competence as a key enabler of sustainability leadership [11]. At TYP, the community-based social enterprise presents a strong organizational culture. The social enterprise also promotes its strong ethical and cultural values toward selfless dedication and altruism to support the sustainable development, consistent with the ethical competence [11]. For generations, the people in this culture have embedded and embraced strong ‘personal connection’ values with love and care for the rich ecological system and cultural heritage. Protecting its nature and nurturing biodiversity in the community becomes the living philosophy and way of living that goes beyond any formal guidelines or regulatory compliance. The community has a strong spiritual connection with the nature as the vital symbol of life on earth. It also treats the mother earth—all trees, rivers and the ocean—with esteemed respect. People in the community and the social enterprise believe that TYP is the “special place to work”, consistent with the literature [93], and the loving and caring community-based social enterprise makes all people and employees feel happy and satisfied. Building the strong organizational culture at the social enterprise also requires the strategic and systematic competencies together with the ethical competence to develop sustainability leadership and organizations [11].

“TYP is a small fishing community surrounded by abundant nature with mountain forests, sea mangroves and rich biodiversity. We love our culture and natural resources. We have to preserve our culture and conserve the environment to pass on to our children and [the] next generations.”—TYP community-based social enterprise’s committee (A)

“Leaders must have the heart to serve and dedicate themselves to the community. I appreciate the strong leadership here. I can feel that the community enterprise leader and members have strong teamwork. If only one person frowns, the whole atmosphere can turn sour. But here they are so warm and friendly. This is the charming magic of TYP.”—A tourist (B)

Moreover, the social enterprise understands the importance of “empowerment to act”. The social entrepreneur empowers its people to act upon the common and strong shared vision and core values to cultivate its strong culture to last for future generations. The meaningful and powerful vision and values toward environmental conservation and cultural preservation for the next generations help empower all organization members’ sense of ownership, emotional commitment, engagement and accountability toward sustainable goals. It offers all-inclusive organizational management systems implicitly and explicitly. It provides education to support knowledge-sharing and learning within the community through regular meetings, story-telling, internal and external training and development from within the enterprise or external sources. It also established a learning center, called “TYP’s Community Forest Nature Study and Ecotourism Center”. The center focuses on a natural resource management project where the community can learn and enhance their analytical thinking. It is also a training venue for the sea and coastal volunteer citizens. There are various programs at the center, including a study visit to improve other community members’ understanding about how they can effectively implement sustainability actions and manage multiple natural resources in the village.

“The TYP’s community forest learning center is set up to create awareness of the importance of the forest conservation. It encourages the people in the community to fully participate and cooperate in organizing responsible tourism activities.”—Head of the TYP community-based social enterprise.

“The TYP’s community forest learning center is open for everyone in the community and visitors, both individuals and groups. It aims to foster relationships between the community and natural resources in TYP. It is the venue for all community members to learn and care for the mangrove forest and surrounding nature. It also provides educational trainings for children and youth in the area to develop their artwork by using the natural biodiversity in the mangrove forest as the source of inspiration. Moreover, the center welcomes all community members and local entrepreneurs to exhibit and sell their environmentally friendly products in the center for visitors and tourists.”—TYP community-based social enterprise committee (B)

The social enterprise envisions that the community-based tourism can be instrumental to enrich its economic prosperity, social equity and environment quality. This vision gives the direction of where people should go or what they should aim for. This clear vision has empowered the enterprise members. They share ownership rights and collective responsibility as well as feel emotionally committed to their cultural and natural resources that are key to the tourist attractions. The finding shows a strong collective responsibility in this CBSE. Collective responsibility focuses on mutual understanding and awareness of tourism development in the village of TYP. The enterprise members accept the shared responsibility for developing tourism initiatives. They follow the CBSE rules and instructions. The collective responsibility also refers to taking care of their cultural and natural heritage assets (e.g., keeping their building fresh and pavement clean) as well as continuously improving their hospitality to enhance the tourist experiences.

“We all have shared responsibility for the development of TYP and the success of our enterprise. All community members fully participate in every activity, as we realize how tourism activities can positively and negatively affect the well-being and sustainability of the community.”—TYP community-based social enterprise’s committee (B)

“It is everyone’s responsibility to keep our village clean. Moreover, we all should be good hosts when tourists visit our village.”—TYP community-based social enterprise’s member (B)

5.4. Innovation

Sustainability leaders foster innovation to achieve long-term growth and competitive advantages. The findings from the case study suggest that the CBSE leader and enterprise members focus on a shared leadership through collective group innovation and collaboration to co-create innovation as a team. They put effort into cultivating an empowered culture to create innovation capability, as suggested by the literature [7,98]. They also work together to decide on initiatives and solutions that are best for them to develop social innovation as well as grow from their traditional cultural and/or rich environmental heritage to enhance social assets and capabilities for long-term success, in line with the previous research [103,104,105]. The evidence also supports the importance of the sustainability leadership competencies, as it illustrates how the social enterprise has innovation as its strategic imperative [11]. It also anticipates how its foresight and innovative initiatives can support socio-economic balance without harms to the ecosystem [8,11].

“Our community members have worked together and shared the ideas on how to capitalize natural resources and cultural heritage sustainably. One of the ideas was to use forests as the protagonist of ecotourism as an innovative initiative. Therefore, it is a sustainable alternative for the TYP community to prevent and reduce the impact on the environment. And, the tourists can directly experience as well as learn from our natural environment and ecosystem.”—Head of the TYP community-based social enterprise

In the case study, it is evident that the social enterprise leader and members help each other to co-design distinctive products and service innovations. The innovative products and hospitality services include distinct tourism programs and activities that exhibit an authentic originality, such as its dawn bathing or sunrise gondola programs. For example, the dawn bathing gondola program allows tourists or visitors to take a cruise from the early morning at 5:00–9:00 a.m. with the local guides and villagers, who escort them to see the sunrise. The dawn or sunrise bathing gondola program in TYP has become the most popular destination and a must-do tourism activity in Lanta Island. This product innovation is a good example of social innovation. The tourism programs aim to present their inimitable cultural heritage of the old-fashioned fishing village as well as promote the natural biodiversity conservation in the mangrove forest to support socio-environmental responsibility.

“The gondola with dawn bathing program has a unique value proposition. Our community is not only selling gondola rides. We sell the philosophy behind it. Tourists do not only enjoy the beauty of mangrove forests during the course, but they also learn to appreciate the nature whilst enhancing their sense of responsibility to the planet. Tourists can appreciate the serenity and art of living.”—Head of the TYP community-based social enterprise