Estimating the Impacts of Non-Tariff Measures in the Indian Ocean Rim Association

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. IORA and NTMs Incidence

3. Model

Data

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Country-Level AVE

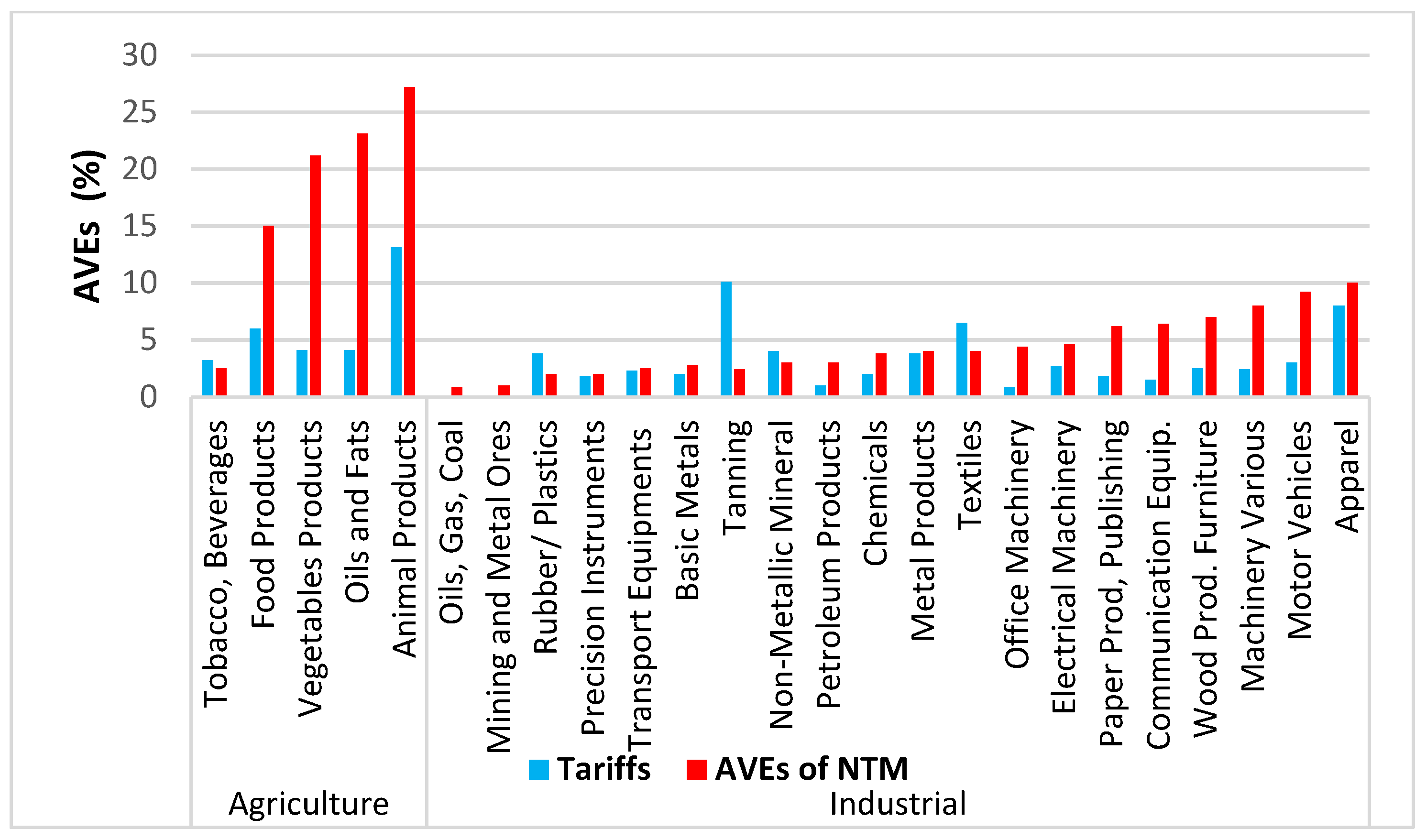

4.2. Chapter-Level AVE in the IORA

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Region | Countries | Income Level |

|---|---|---|

| Australasia | Australia | High |

| Southeast Asia | Indonesia | Upper Middle |

| Malaysia | Upper Middle | |

| Singapore | High | |

| Thailand | Upper Middle | |

| South Asia | Bangladesh | Lower Middle |

| India | Lower Middle | |

| Maldives | Upper Middle | |

| Sri Lanka | Lower Middle | |

| West Asia | Iran | Upper Middle |

| Oman | High | |

| UAE | High | |

| Yemen | Low | |

| Eastern Africa | Comoros | Low |

| Kenya | Lower Middle | |

| Madagascar | Low | |

| Mauritius | High | |

| Seychelles | High | |

| Somalia | Low | |

| Tanzania | Lower Middle | |

| Southern Africa | Mozambique | Low |

| South Africa | Upper Middle | |

| France (Reunion Island) |

| Imports | ||

|---|---|---|

| Technical Measures | A | Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures |

| B | Technical Barriers to Trade | |

| C | Pre-Shipment Inspection and Other Formalities | |

| Non-Technical Measures | D | Contingent Trade-Protective Measures |

| E | Non-Automatic Licensing, Quotas, Prohibitions and Quantity-Control Measures Other Than for SPS or TBT Reasons | |

| F | Price-Control Measures, Including Additional Taxes and Charges | |

| G | Finance Measures | |

| H | Measures Affecting Competition Procurement Restrictions, Intellectual Property and Rules of Origin | |

| I | Trade-Related Investment Measures | |

| J | Distribution Restrictions | |

| K | Restrictions on Post-Sales Services | |

| L | Subsidies (Excluding Export Subsidies Under P7) | |

| M | Government Procurement Restrictions | |

| N | Intellectual Property | |

| O | Rules of Origin | |

| Exports | ||

| P | Export-Related Measures | |

| HS 2 | Description | SPS | TBT | QR | SG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Live animals and products | 0.020 | −0.087 | . | . |

| 2 | Meat and edible meat offal | . | −0.003 | −1.338 | . |

| 3 | Fish and crustaceans, molluscs, … | . | −0.002 | . | . |

| 4 | Dairy produce, birds’ eggs, … | 0.002 | −0.008 | 3.164 | . |

| 5 | Products of animal origin, … | . | 0.000 | 0.147 | . |

| 6 | Live trees and other plants, … | . | . | . | . |

| 7 | Edible vegetables and certain… | −0.004 | 0.003 | . | . |

| 8 | Edible fruit and nuts, … | . | −0.002 | . | . |

| 9 | Coffee, tea, … | . | . | . | . |

| 10 | Cereals | . | −0.045 | 1.582 | . |

| 11 | Products of the milling industry, … | −0.005 | 0.004 | . | −0.071 |

| 12 | Oilseeds and oleaginous fruits, … | . | . | −0.291 | . |

| 13 | Lac, gums, resins, … | . | . | −0.867 | . |

| 14 | Vegetable plaiting materials, … | . | 0.449 | . | . |

| 15 | Animal or vegetable fats and oils, … | . | . | −0.019 | . |

| 16 | Preparations of meat, of fish, … | −0.016 | −0.010 | −5.161 | . |

| 17 | Sugars and sugar confectionery | . | −0.021 | . | . |

| 18 | Cocoa and cocoa preparations | −0.043 | . | . | . |

| 19 | Preparations of cereals, flour, … | 0.006 | 0.000 | . | . |

| 20 | Preparations of vegetables, … | . | −0.005 | . | 4.490 |

| 21 | Miscellaneous edible preparations | 0.029 | −0.015 | . | . |

| 22 | Beverages, spirits and vinegar | . | −0.006 | . | . |

| 23 | Residues and waste from… | 0.005 | −0.007 | −12.529 | . |

| 24 | Tobacco and manufactured… | −1.376 | −0.196 | 36.032 | . |

| 25 | Salt, sulfur, earth and stone, … | 0.057 | −0.002 | 0.054 | . |

| 26 | Ores, slag and ash | . | . | . | . |

| 27 | Mineral fuels, mineral oils, … | . | 0.041 | . | . |

| 28 | Inorganic chemicals, organic… | . | . | 0.064 | . |

| 29 | Organic chemicals | . | . | −0.007 | −0.333 |

| 30 | Pharmaceutical products | . | −0.026 | −0.035 | . |

| 31 | Fertilizers | . | . | 0.703 | . |

| 32 | Tanning or dyeing extracts, … | −1.838 | . | . | . |

| 33 | Essential oils and resinoids, … | . | −0.001 | . | . |

| 34 | Soap, organic surface-active… | . | −0.024 | 0.637 | . |

| 35 | Albuminoidal substances, … | 67.224 | . | 11.209 | −8.655 |

| 36 | Explosives, pyrotechnics, … | . | 0.028 | 0.572 | . |

| 37 | Photographic or cinematographic… | . | . | . | . |

| 38 | Miscellaneous chemical products | 0.065 | −0.036 | . | . |

| 39 | Plastics and articles thereof | . | . | 0.169 | . |

| 40 | Rubber and articles thereof | . | −0.021 | 0.230 | 1.922 |

| 41 | Raw hides and skins… | . | 0.004 | 1.918 | . |

| 42 | Articles of leather, saddlery, … | . | 0.138 | . | . |

| 43 | Furskins and artificial fur, … | −1.771 | . | 0.584 | . |

| 44 | Wood and articles of wood, … | . | 0.062 | . | −0.923 |

| 45 | Cork and articles of cork | . | . | . | . |

| 46 | Manufactures of straw, … | . | 0.418 | . | . |

| 47 | Pulp of wood or other fibrous… | . | 0.762 | . | . |

| 48 | Paper and paperboard, … | 0.232 | 0.017 | 0.141 | 12.546 |

| 49 | Printed books, newspapers, … | . | 0.000 | 3.233 | . |

| 50 | Silk | . | 0.040 | . | . |

| 51 | Wool, fine or coarse… | . | . | 1.729 | . |

| 52 | Cotton | 3.000 | . | 0.339 | −0.232 |

| 53 | Other vegetable textile fibres, … | . | . | −4.476 | . |

| 54 | Man-made filaments | . | −0.032 | −0.545 | . |

| 55 | Man-made staple fibers | . | 0.000 | . | . |

| 56 | Wadding, felt and nonwovens, … | . | . | . | . |

| 57 | Carpets and other textile floor… | . | 0.043 | . | . |

| 58 | Special woven fabrics, … | . | . | . | . |

| 59 | Impregnated, coated, covered… | . | . | . | −2.344 |

| 60 | Knitted or crocheted fabrics | . | 0.095 | . | . |

| 61 | Articles of apparel and clothing… | −0.046 | . | −0.013 | . |

| 62 | Articles of apparel and clothing… | −0.025 | . | −0.186 | . |

| 63 | Other made-up textile articles, … | . | 0.045 | . | −7.205 |

| 64 | Footwear, gaiters and the like, … | −0.107 | . | 0.872 | . |

| 65 | Headgear and parts thereof | . | 0.161 | 7.469 | . |

| 66 | Umbrellas, sun umbrellas, … | . | 0.537 | . | . |

| 67 | Prepared feathers… | . | −0.694 | . | . |

| 68 | Articles of stone, plaster, … | . | −0.005 | . | . |

| 69 | Ceramic products | . | . | . | . |

| 70 | Glass and glassware | . | . | . | . |

| 71 | Natural or cultured pearls, … | . | . | . | . |

| 72 | Iron and steel | . | . | −0.279 | . |

| 73 | Articles of iron or steel | 0.263 | . | . | −0.415 |

| 74 | Copper and articles thereof | . | −0.130 | . | . |

| 75 | Nickel and articles thereof | . | 0.775 | 0.077 | . |

| 76 | Aluminum and articles thereof | . | −0.103 | . | . |

| 78 | Lead and articles thereof | . | . | . | . |

| 79 | Zinc and articles thereof | . | . | . | . |

| 80 | Tin and articles thereof | . | −0.896 | 2.122 | . |

| 81 | Other base metals, cermets, … | . | 0.203 | . | . |

| 82 | Tools, implements, cutlery, … | . | −0.038 | . | . |

| 83 | Miscellaneous articles… | . | −0.244 | . | . |

| 84 | Nuclear reactors, boilers, … | . | −0.004 | . | . |

| 85 | Electrical machinery and equipment, … | . | . | . | . |

| 86 | Railway or tramway locomotives, … | . | −6.851 | 2.626 | . |

| 87 | Vehicles other than railway… | −3.594 | . | . | −1.050 |

| 88 | Aircraft, spacecraft, and… | . | . | . | . |

| 89 | Ships, boats and floating… | . | −0.141 | −4.116 | . |

| 90 | Optical, photographic… | . | −0.004 | . | −2.034 |

| 91 | Clocks and watches… | . | . | 0.785 | . |

| 92 | Musical instruments, parts and… | . | . | . | . |

| 93 | Arms and ammunition, parts… | . | 0.278 | . | . |

| 94 | Furniture, bedding, mattresses, … | −46.767 | −0.058 | . | . |

| 95 | Toys, games and sports, … | . | 0.027 | . | . |

| 96 | Miscellaneous manufactured… | . | . | 0.593 | . |

| 97 | Works of art, collectors’ pieces… | . | . | . | . |

| Sector | SPS | TBT | QR | SG |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agrifood | −0.138 | 0.003 | 2.072 | 2.210 |

| Manufacturing | 1.284 | −0.144 | 0.913 | −0.793 |

References

- WTO. World Trade Report 2013: Factors Shaping the Future of World Trade; World Trade Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- UNCTAD. International Trade Statistics Yearbook, 2017; United Nations Conference on Trade and Development: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Disdier, A.-C.; Fontagné, L.; Cadot, O. North-South standards harmonization and international trade. World Bank Econ. Rev. 2015, 29, 327–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNCTAD. Non-Tariff Measures and Sustainable Development Goals: Direct and Indirect Linkages; United Nations Conference on Trade and Development: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zainuddin, M.R.K.; Sarmidi, T.; Khalid, N. Sustainable production, non-tariff measures, and trade performance in RCEP countries. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandaruwan, K.; Weerasooriya, S.A. Non-Tariff Measures and Sustainable Development: The Case of the European Union Import Ban on Seafood from Sri Lanka; ARTNeT Working Paper Series; ESCAP: Bangkok, Thailand, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kravchenko, A.; Semenova, M.; Lee, S.; Duval, Y. Exploring Linkages between Non-Tariff Measures and the Sustainable Development Goals: A Global Concordance Matrix and Application to Asia and the Pacific; ESCAP: Bangkok, Thailand, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Prabhakar, D. COVID-19 Non-Tariff Measures: The Good and the Bad, Through a Sustainable Development Lens; UN: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Council, A.B.A. Non-Tariff Barriers in Agriculture and Food Trade in APEC: Business Perspectives on Impacts and Solutions. University of Southern California. 2016. Available online: https://www.ncapec.org/docs (accessed on 10 June 2021).

- UNCTAD. Non-Tariff Measures to Trade: Economic and Policy Issues for Developing Countries; United Nations Conference on Trade and Development: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Beghin, J.C.; Disdier, A.C.; Marette, S. Trade restrictiveness indices in the presence of externalities: An application to non-tariff measures. Can. J. Econ. Rev. Can. D’économique 2015, 48, 1513–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratt, M. Estimating the bilateral impact of non-tariff measures (NTMs)(No. 14011). Rev. Int. Econ. 2017, 25, 1105–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ing, L.Y.; Cadot, O. Ad Valorem Equivalents of Non-Tariff Measures in ASEAN; ERIA: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cadot, O.; Gourdon, J. NTMs, Preferential Trade Agreements, and Prices: New Evidence; CEPI: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nes, K.; Schaefer, K.A. Retaliatory Use of Public Standards in Trade; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- UNCTAD. Asia-Pacific Trade and Investment Report 2019: Navigating Non-Tariff Measures towards Sustainable Development; United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific: Bangkok, Thailand, 2019; p. 130. [Google Scholar]

- IORA. The Study On Bilateral and Regional Trade and Investment Related Agreements and Dialogues Between Member States; Indian Ocean Rim Association: Ebene, Mauritius, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dabee, B.; Reddy, M. Regional agreements in the Indian ocean. World Econ. 2000, 23, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K. Agricultural Trade Liberalization: Implications for Indian Ocean. Rim Countries; Centre for International Economic Studies: Adelaide, Australia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kelegama, S. Can Open Regionalism Work in the Indian Ocean Rim Association for Regional Co-operation? ASEAN Econ. Bull. 1998, 15, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelegama, S. Open Regionalism in the Indian Ocean: How relevant is the APEC model for IOR-ARC? J. Asia Pac. Econ. 2000, 5, 255–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euromonitor. IORA Selected Economic Indicators; Indian Ocean Rim Association: Ebene, Mauritius, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Boughanmi, H.; Akintola, A.; Kotagama, H.; Zaibet, L. Looking East: Oman’s trade integration in the Indian Ocean. Rim Association (IORA); Global Trade Analysis Project (GTAP): West Lafayette, IN, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mohanty, S.K.; Dash, P. Trade and Investment Prospects of the IORA in the New Millennium New Economic Frontiers of the Region; 2015. Available online: https://iora.ris.org.in/trade-and-investment-prospects-iora-new-millennium-new-economic-frontiers-region (accessed on 2 May 2019).

- UNCTAD; World Bank. The Unseen Impact of Non-Tariff Measures: Insights from a New Database; UNCTAD: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Disdier, A.-C.; Fugazza, M. A Practical Guide to the Economic Analysis of Non-Tariff Measures; United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Breaux, M.; Cabral, Y.; Signoret, J.; Ferrantino, M.J. Quality-Adjusted Estimates of NTM Price Gaps; US Internat. Trade Commission, Office of Economics: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Looi Kee, H.; Nicita, A.; Olarreaga, M. Estimating trade restrictiveness indices. Econ. J. 2009, 119, 172–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghodsi, M.; Gruebler, J.; Stehrer, R. Estimating Importer-Specific ad Valorem Equivalents of Non-Tariff Measures; Wiiw Working Paper; The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies: Vienna, Austria, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nicita, A.; Jaime, D.E. Non-Tariff Measures: Data and Quantitative Tools of Analysis. 2018. Available online: https://ferdi.fr/dl/df-pwFsQKwSBf2Djde77ELncfwt/ferdi-p218-non-tariff-measures-data-and-quantitative-tools-of-analysis.pdf (accessed on 23 May 2019).

- Kee, H.L.; Nicita, A.; Olarreaga, M. Ad Valorem Equivalents of Non-Tariff Barriers; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Arvis, J.-F.; Shepherd, B. The Poisson quasi-maximum likelihood estimator: A solution to the ‘adding up’problem in gravity models. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2013, 20, 515–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Silva, J.S.; Tenreyro, S. The log of gravity. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2006, 88, 641–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yotov, Y.V.; Piermartini, R.; Monteiro, J.-A.; Larch, M. An Advanced Guide to Trade Policy Analysis: The Structural Gravity Model; World Trade Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, Z.; Liu, C.; Gunessee, S.; Milner, C. Non-tariff and overall protection: Evidence across countries and over time. Rev. World Econ. 2018, 154, 675–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baier, S.L.; Bergstrand, J.H. Bonus vetus OLS: A simple method for approximating international trade-cost effects using the gravity equation. J. Int. Econ. 2009, 77, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mátyás, L. Proper econometric specification of the gravity model. World Econ. 1997, 20, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghodsi, M.; Grübler, J.; Stehrer, R. Bilateral Import Elasticities of Demand; Wiiw: Vienna, Austria, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ghodsi, M.; Reiter, O.; Stehrer, R. Compilation of a Database for Non-Tariff Measures from the WTO Integrated Trade Intelligence Portal (WTO I-TIP); Paper written in the PRONTO project, work in progress; wiiw: Vienna, Austria, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Feenstra, R.C.; Inklaar, R.; Timmer, M.P. The next generation of the Penn World Table. Am. Econ. Rev. 2015, 105, 3150–3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ronen, E. Quantifying the trade effects of NTMs: A review of the empirical literature. J. Econ. Political Econ. 2017, 4, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Percentage of IORA Notifications Compared to World Notifications | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measures | SPS | TBT | ADP | CV | SG | SSG | QR | TRQ | XS | Total |

| IORA | 1822 | 3607 | 538 | 29 | 3 | 557 | 98 | 45 | 7227 | |

| World | 15,145 | 19,256 | 1980 | 234 | 12 | 1379 | 1821 | 1279 | 379 | 41,289 |

| Percent | 12.03 | 18.73 | 27.17 | 12.39 | 25.00 | 0.00 | 30.59 | 7.66 | 11.87 | 17.50 |

| Notification of Agricultural Products as a Percentage of Total Products in the IORA | ||||||||||

| SPS | TBT | ADP | CV | SG | SSG | QR | TRQ | XS | Total | |

| Agricultural Products | 1656 | 1414 | 25 | 6 | 175 | 94 | 38 | 3291 | ||

| Total Products | 1822 | 3607 | 538 | 29 | 3 | 557 | 98 | 45 | 7227 | |

| Percent | 90.89 | 39.20 | 4.65 | 20.69 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 31.42 | 95.92 | 84.44 | 45.54 |

| Importer | SPS | TBT | QR | SG | Tariff |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UAE | 0.026 | −87.007 | . | −4.396 | 4.5 |

| Australia | 0.055 | −0.164 | −0.007 | . | 2 |

| Indonesia | 0.009 | −0.046 | . | −0.702 | 5 |

| India | −0.028 | −0.012 | . | −0.881 | 12.8 |

| Kenya | 0.005 | −0.009 | . | . | 9.2 |

| Mauritius | −0.142 | . | . | . | 0.6 |

| Malaysia | 0.487 | −0.444 | . | . | 4.5 |

| Oman | 0.400 | −1.618 | . | 37.885 | 4.6 |

| Singapore | 95.771 | . | . | . | 0 |

| Tanzania | −0.698 | . | . | 9.7 | |

| South Africa | −0.010 | −0.019 | . | −8.250 | 6.3 |

| Description | SPS | TBT | QR | SG | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I: (01–05) | Live animals and products | 0.011 | −0.020 | 0.658 | . |

| II: (06–14) | Vegetable products | −0.004 | 0.082 | 0.141 | −0.071 |

| III: (15–15) | Animal and vegetable fats, oils and waxes | . | . | −0.019 | . |

| IV: (16–24) | Prepared foodstuffs, bevearges, spirits, vinegar and tobacco | −0.232 | −0.033 | 6.114 | 4.490 |

| V: (25–27) | Mineral products | 0.057 | 0.020 | 0.054 | . |

| VI: (28–38) | Products of chemical and allied industries | 21.817 | −0.012 | 1.878 | −4.494 |

| VII: (39–40) | Resins, plastics and articles and rubber and articles | −0.021 | 0.199 | 1.922 | |

| VIII: (41–43) | Hides, skins and articles, saddlery and travel goods | −1.771 | 0.071 | 1.251 | |

| IX: (44–46) | Wood, cork and articles and basket wares | 0.240 | −0.923 | ||

| X: (47–49) | Paper, paperboard and articles | 0.232 | 0.259 | 1.687 | 12.546 |

| XI: (50–63) | Textiles and articles | 0.976 | 0.032 | −0.525 | −3.260 |

| XII: (64–67) | Footwear, headgear, feathers, artificial flowers and fans | −0.107 | 0.001 | 4.171 | |

| XIII: (68–70) | Articles of stones, plaster, ceramic products and glass | −0.005 | |||

| XIV: (71–71) | Pearls, precious stones and metals and coins | ||||

| XV: (72–83) | Base metals and articles | 0.263 | −0.062 | 0.640 | −0.415 |

| XVI: (84–85) | Machinery and electrical equipment | −0.004 | |||

| XVII: (86–89) | Vehicles, aircraft and vessels | −3.594 | −3.496 | −0.745 | −1.050 |

| XVIII: (90–92) | Instruments, clocks, recorders and reproducers | −0.004 | 0.785 | −2.034 | |

| XIX: (93–93) | Arms and ammunition | 0.278 | |||

| XX: (94–96) | Miscellaneous manufactured articles | −46.767 | −0.015 | 0.593 | |

| XXI: (97–97) | Works of art and antiques |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Akintola, A.; Boughanmi, H.; Antimiani, A.; Zaibet, L.; Kotagama, H. Estimating the Impacts of Non-Tariff Measures in the Indian Ocean Rim Association. Sustainability 2022, 14, 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010068

Akintola A, Boughanmi H, Antimiani A, Zaibet L, Kotagama H. Estimating the Impacts of Non-Tariff Measures in the Indian Ocean Rim Association. Sustainability. 2022; 14(1):68. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010068

Chicago/Turabian StyleAkintola, Abdallah, Houcine Boughanmi, Alessandro Antimiani, Lokman Zaibet, and Hemesiri Kotagama. 2022. "Estimating the Impacts of Non-Tariff Measures in the Indian Ocean Rim Association" Sustainability 14, no. 1: 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010068

APA StyleAkintola, A., Boughanmi, H., Antimiani, A., Zaibet, L., & Kotagama, H. (2022). Estimating the Impacts of Non-Tariff Measures in the Indian Ocean Rim Association. Sustainability, 14(1), 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010068