Challenges for the Integrated Management of Priority Areas for Conservation in Tamaulipas, México

Abstract

1. Introduction

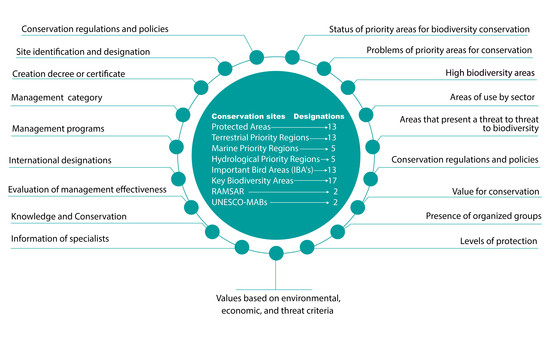

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Site Identification and Designations

2.2. Determination of Criteria for the Analysis of Each Site

2.3. Interviews with Experts

- How were the priority areas designated?

- (Natural Protected Areas, Priority Terrestrial Regions, Priority Marine Regions, Priority Hydrological Regions, AICAS/IBAS in which you participated)

- Who convened the meeting? Who participated? What is the basis?

- What has been the importance of priority areas?

- What impact have they had on conservation?

- Is conservation monitoring carried out? How is the performance of those responsible for these areas?

- What challenges do the management and conservation of priority areas present?

- What is the status of conservation schemes?

- What are the structures or systems of support?

- Do they have a structure, budget, and staff?

- Who would be the relevant actors in the process of developing the state system of priority areas for conservation?

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Documental Analysis

3.2. Conservation Regulations and Policies

3.2.1. Natural Protected Areas in Tamaulipas

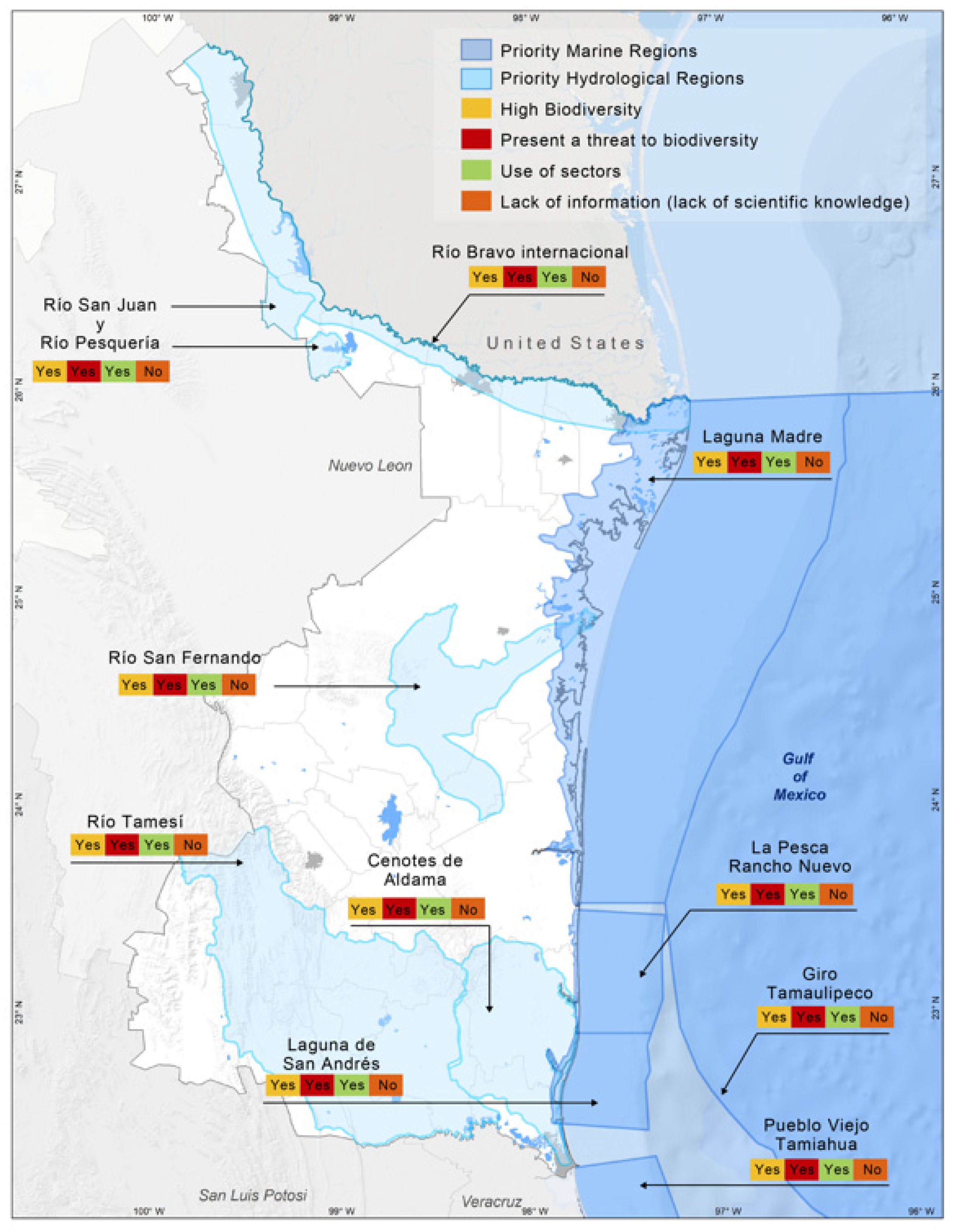

3.2.2. Priority Regions

3.3. Status of Priority Areas for Biodiversity Conservation

3.3.1. Natural Protected Areas

3.3.2. Priority Terrestrial Regions (PTRs)

- The knowledge and conservation policy status are reported with a brief description; therefore, following the same criteria as the variables already rated in the card, they were converted into numbers of conservation policies: 3 (integrated actions), 2 (some actions), 1 (incipient or some interest) and 0 (non-existent). Knowledge: 3 (well known), 2 (known), 1 (little known) and 0 (not known).

- Information, including the citation where the information was obtained, the name of the specialists who participated in the information gathering and, in some cases, the institutions where the information was obtained. It was found that 42 national and international experts, students and thesis students participated in the survey, including Dr. L. Arriaga, Dr. E. Enkerlin and F. González-Medrano, assigned at that time to CONABIO, Pronatura and the Institute of Ecology of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), respectively.

3.3.3. Priority Marine Regions (PMRs)

3.3.4. Priority Hydrologic Regions (PHRs)

3.3.5. Important Bird Areas (IBAs)

3.3.6. Key Biodiversity Areas (KBAs)

3.3.7. International Designations

3.4. Problems of Priority Areas for Conservation in Tamaulipas

3.5. Interviews with Experts

3.5.1. Question 1. How Were the Priority Areas Identified?

3.5.2. Question 2. What has been the Importance of the Priority Areas?

3.5.3. Question 3. What Challenges do Their Management and Conservation Present?

Legal Basis—Compliance with Regulations

Paper Areas

Lack of State and Federal Structure

Absence of Evaluation and Monitoring

Lack of Commitment for Effective Management

Manage the Participation of Different Stakeholders and Sectors

Updating Information and Incorporating the Social Context

Lack of Transversality

4. Discussion

4.1. Conservation, Regulation and Policies

4.2. Status of Priority Areas for Diversity Conservation

4.3. Problems of the Priority Areas for Conservation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Borrini-Feyerabend, G.; Dudley, N.; Jaeger, T.; Lassen, B.; Pathak, N.; Philips, A.; Sandwith, T.; Protegidas, Á. Gobernanza de Áreas Protegidas: De la Comprensión a la Acción; UICN: Gland, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Palomo, I.; Martín-López, B.; Zorrilla-Miras, P.; del Amo, D.; Montes, C. Deliberative Mapping of Ecosystem Services within and around Doñana National Park (SW Spain) in Relation to Land Use Change. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2013, 14, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawhall, N. Influencias Sociales y Económicas Que Moldean las Áreas Protegidas; Worboys, G.L., Lockwood, M., Kothari, S., Feary, E., Pulsford, I., Eds.; Gobernanza y Gestión de Areas Protegidas. Editorial Universidad El Bosque y ANU Press: Bogotá, Colombia, 2019; pp. 119–148. [Google Scholar]

- He, M.; Cliquet, A. Challenges for Protected Areas Management in China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopoukhine, N.; Crawhall, N.; Dudley, N.; Figgis, P.; Karibuhoye, C.; Laffoley, D.; Londoño, J.; MacKinnon, K.; Sandwith, T. Protected Areas: Providing Natural Solutions to 21st Century Challenges. Sapiens 2012, 5, 116–131. [Google Scholar]

- Woodley, S.; Locke, H.; Laffoley, D.; MacKinnon, K.; Sandwith, T.; Smart, J. A Review of Evidence for Area-based Conservation Targets for the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework. PARKS 2019, 25, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackinnon, K.; Mrema, E.M.; Richardson, K.; Cooper, D.; Gidda, S. Editorial Essay: Protected and Conserved Areas: Contributing to More Ambitious Conservation Outcomes Post-2020. PARKS 2021, 27, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulongoy, K.J.; Babu Gidda, S. The Value of Nature: Ecological, Economic, Cultural and Social Benefits of Protected Areas; Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Loos, J. Reconciling Conservation and Development in Protected Areas of the Global South. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2021, 54, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrini-Feyerabend, G.; Hill, R. Gobernanza Para La Conservación de La Naturaleza; ANU Press: Canberra, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Pimm, S.; Du, A.; Su, Y.; Fan, X.; An, L.; Liu, J.; Ouyang, Z. Transforming Protected Area Management in China. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2019, 34, 762–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geldmann, J.; Coad, L.; Barnes, M.; Craigie, I.; Hockings, M.; Knights, K.; Leverington, F.; Cuadros, I.; Zamora, C.; Woodley, S.; et al. Changes in Protected Area Management Effectiveness over Time: A Global Analysis. Biol. Conserv. 2015, 191, 692–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coad, L.; Watson, J.; Geldmann, J.; Burgess, N.; Leverington, F.; Hockings, M.; Knights, K.; di Marco, M. Widespread Shortfalls in Protected Area Resourcing Undermine Efforts to Conserve Biodiversity. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2019, 17, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visconti, P.; Butchart, S.; Brooks, T.; Langhammer, P.; Marnewick, D.; Vergara, S.; Yanosky, A.; Watson, J. Protected Area Targets Post-2020. Science 2019, 364, eaav6886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukul, S.A.; Sohel, M.S.I.; Herbohn, J.; Inostroza, L.; König, H. Integrating Ecosystem Services Supply Potential from Future Land-Use Scenarios in Protected Area Management: A Bangladesh Case Study. Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 26, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Peng, L.; Liu, S. Analysis of the Network of Protected Areas in China Based on a Geographic Perspective: Current Status, Issues and Integration. Sustainability 2015, 7, 15617–15631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hockings, M.; Dudley, N.; Ellio, W.; Ferreira, M.; Mackinnon, K.; Pasha, M.; Phillips, A.; Stolton, S.; Woodley, S.; Appleton, M.; et al. COVID-19 and Protected and Conserved Areas. PARKS 2020, 26, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margules, C.; Pressey, R. Systematic Conservation Planning. Nature 2000, 405, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, S.L.; Cazalis, V.; Dudley, N.; Hoffmann, M.; Rodrigues, A.S.L.; Stolton, S.; Visconti, P.; Woodley, S.; Kingston, N.; Lewis, E.; et al. Author Correction: Area-Based Conservation in the Twenty-First Century. Nature 2020, 588, E14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dearden, P.; Bennett, M.; Johnston, J. Trends in Global Protected Area Governance, 1992–2002. Environ. Manag. 2005, 36, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lockwood, M.; Worboys, G.; Kothari, A. Managing Protected Areas: A Global Guide; Earthscan: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Spoelder, P.; Lockwood, M.; Cowell, S.; Gregerson, P.; Henchman, A. Planeación. In Gobernanza y Gestión de Áreas Protegidas; ANU Press: Canberra, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Worboys, G. Concept, Purpose and Challenges; ANU Press: Canberra, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, F.; Sánchez-Cordero, V. Effectiveness of Natural Protected Areas to Prevent Land Use and Land Cover Change in Mexico. Biodivers. Conserv. 2008, 17, 3223–3240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. A General Framework for Analyzing Sustainability of Social-Ecological Systems. Science 2009, 325, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz, S.; Settele, J.; Brondízio, E.S.; Ngo, H.T.; Agard, J.; Arneth, A.; Balvanera, P.; Brauman, K.A.; Butchart, S.H.M.; Chan, K.M.A.; et al. Pervasive Human-Driven Decline of Life on Earth Points to the Need for Transformative Change. Science 2019, 366, eaax3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo, V.M. El Metabolismo Social: Una Nueva Teoría Socioecológica. Relac. Estud. Hist. Soc. 2013, 34, 41–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevance, A.-S.; Bridgewater, P.; Louafi, S.; King, N.; Beard, T.; van Jaarsveld, A.; Ofir, Z.; Kohsaka, R.; Jenderedijan, K.; Rosales, M.; et al. The 2019 Review of IPBES and Future Priorities: Reaching beyond Assessment to Enhance Policy Impact. Ecosyst. People 2019, 16, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldekop, J.; Holmes, G.; Harris, W.; Evans, K. A Global Assessment of the Social and Conservation Outcomes of Protected Areas. Conserv. Biol. 2015, 30, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, S.E.; Pittman, S.J.; Foster, N.; Langmead, O.; Griffiths, C.; Fletcher, S.; Johnson, D.E.; Attrill, M. Bridging the Divide: Social-Ecological Coherence in Marine Protected Area Network Design. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2018, 28, 754–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Cliquet, A. Sustainable Development through a Rights-Based Approach to Conserve Protected Areas in China. China-EU Law J. 2014, 3, 143–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Xu, W.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yang, W.; Zhang, L.; Hull, V.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, H.; Liu, J.; Polasky, S.; et al. Strengthening Protected Areas for Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services in China. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 1601–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petursson, J.G.; Kristofersson, D.M. Co-Management of Protected Areas: A Governance System Analysis of Vatnajökull National Park, Iceland. Land 2021, 10, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arriaga, L.; Espinoza, J.M.; Aguilar, C.; Martínez, E.; Gómez, L.; Loa, E. Regiones Terrestres Prioritarias de México; Comisión Nacional Para El Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad: Ciudad de Mexico, Mexico, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Benítez, H.; Arizmendi, C.; Márquez, L. Base de Datos de Las AICAS. CIPAMEX, CONABIO, FMCN y CCA. México. 1999. Available online: http://www.conabio.gob.mx (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Bezaury-Creel, J.; Gutiérrez-Carbonell, D.; Remolina, J.F. Áreas Naturales Protegidas y Desarrollo Social En México. Cap. Nat. México 2009, 2, 385–431. [Google Scholar]

- Equipo Editorial. Declaración de Helsinki de La Asociación Médica Mundial. Arbor. Cienc. Pensam. Cult. 2008, 184, 730. [Google Scholar]

- ATLAS.ti. Available online: https://atlasti.com/es/ (accessed on 12 September 2021).

- Diario Oficial de la Federación. Ley General Del Equilibrio Ecológico y La Protección al Ambiente. 1988. Available online: http://www.paot.mx/centro/leyes/federales/pdf/2015/LEY_GENERAL_EQUILIBRIO_ECOLOGICO_09_01_2015.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2021).

- Periódico Oficial el Gobierno del Estado de Tamaulipas. Decreto Expedido por el Ejecutivo del Estado por Medio del Cual, por Causa de Utilidad Pública, Se Declara Área Ecológica Protegida, Clasificada como Reserva de la Biosfera El Cielo; Secretaría General del Gobierno del Estado de Tamaulipas (SGG): Ciudad Victoria, Mexico, 1985.

- Diario Oficial de la Federación. DECRETO Por el Que se Determinan Como Zonas de Reserva y Sitios de Refugio para la Protección, Conservación, Repoblación, Desarrollo y Control, de las Diversas Especies de Tortuga Marina, Los Lugares En Que Anida y Desova Dicha Especie; Diario Oficial de la Federación: Ciudad de México, México, 1986.

- Periódico Oficial el Gobierno del Estado de Tamaulipas. Acuerdo Gubernamental Mediante el Cual se Declara Área Protegida Ecológica La Zona Denominada “Colonia Parras de La Fuente”, del Municipio de Abasolo Tamaulipas; Periódico Oficial el Gobierno del Estado de Tamaulipas: Ciudad Victoria, Mexico, 1992.

- Periódico Oficial el Gobierno del Estado de Tamaulipas. Acuerdo Gubernamental Mediante el Cual se Declara Área Natural Protegida, Clasificada Como Parque Urbano El Área Denominado “Laguna La Escondida”, del Municipio de Reynosa, Tamaulipas; Periódico Oficial el Gobierno del Estado de Tamaulipas: Ciudad Victoria, Mexico, 1997.

- Periódico Oficial el Gobierno del Estado de Tamaulipas. Acuerdo Gubernamental Mediante el Cual se Declara Área Natural Protegida, Clasificada Como Monumento Natural, a la Zona Denominada Como “Bernal de Horcasitas”, Que Se Localiza en el Municipio de González, Tamaulipas; Periódico Oficial el Gobierno del Estado de Tamaulipas: Ciudad Victoria, Mexico, 1997.

- Periódico Oficial el Gobierno del Estado de Tamaulipas. Acuerdo Gubernamental Mediante el Cual se Declara Área Natural Protegida, Clasificada Como Zona Especial Sujeta a Conservación Ecológica Con el Nombre de “Área Natural Protegida Altas Cumbres”, del Municipio de Ciudad Victoria, Tamaulipas; Periódico Oficial el Gobierno del Estado de Tamaulipas: Ciudad Victoria, Mexico, 1997.

- Periódico Oficial el Gobierno del Estado de Tamaulipas. Acuerdo Municipal, Mediante el Cual se Declara Área Natural Protegida, Clasificada Como Zona Especial Sujeta a Conservación Ecológica el Área Denominada “LA VEGA ESCONDIDA”, Ubicada En El Municipio de Tampico, Tamaulipas; Periódico Oficial el Gobierno del Estado de Tamaulipas: Ciudad Victoria, Mexico, 1997.

- Diario Oficial de la Federación. DECRETO Por el Que Se Declara Área Natural Protegida, con el Carácter de Área de Protección de Flora y Fauna, la Región Conocida como Laguna Madre y Delta del Río Bravo, Ubicada en los Municipios de Matamoros, San Fernando y Soto La Marina, en el Estado de Tamaulipas. Available online: http://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=4919407&fecha=14/04/2005 (accessed on 11 September 2021).

- CONANP. Áreas Destinadas Voluntariamente a La Conservación: Número de Certificado: CONANP-42/2006: Rancho San Pedro: Antiguo Morelos, Tamaulipas; CONANP: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2006.

- CONANP. Áreas Destinadas Voluntariamente a La Conservación: Número de Certificado: CONANP-249/2011: Reserva Bio Ventura: Aldama, Tamaulipas; CONANP: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2011.

- CONANP. Áreas Destinadas Voluntariamente a La Conservación. Número de Certificado: CONANP-447/2019: Rancho Regalo de Dios: Ocampo, Tamaulipas; CONANP: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2019.

- Periódico Oficial el Gobierno del Estado de Tamaulipas. DECRETO Gubernamental por el Que se Declara Como Área Natural Protegida con la Categoría de Parque Estatal, Denominado “el Refugio”, Localizado en el Municipio de Victoria, Tamaulipas; Periódico Oficial el Gobierno del Estado de Tamaulipas: Ciudad Victoria, Mexico, 2015.

- Diario Oficial de la Federación. DECRETO por el Que se Declara Área Natural Protegida, con el Carácter de Reserva de la Biosfera, la Región Conocida como Sierra de Tamaulipas, Localizada en los Municipios de Aldama, Casas, González, Llera y Soto La Marina, en el Estado de Tamaulipas. Available online: https://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5464453&fecha=07/12/2016 (accessed on 11 September 2021).

- CONANP. Primer Informe Nacional de Evaluación de La Efectividad del Manejo de las Áreas Naturales Protegidas de México Abril 2020 Ciudad de México; CONANP: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2020.

- UNEP-WCMC (2021). Protected Area Profile for Laguna Madre from the World Database of Protected Areas, December 2021. Available online: www.protectedplanet.net (accessed on 8 September 2021).

- BirdLife International. World Database of Key Biodiversity Areas. Developed by the KBA Partnership: BirdLife International, International Union for the Conservation of Nature, American Bird Conservancy, Amphibian Survival Alliance, Conservation International, Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund, Global Environment Facility, Global Wildlife Conservation, NatureServe, Rainforest Trust, Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, Wildlife Conservation Society and World Wildlife Fund. September 2020. Available online: http://www.keybiodiversityareas.org/site/requestgis (accessed on 11 September 2021).

- Key Biodivesity Areas. Key Biodivesity Areas Data. Available online: http://www.keybiodiversityareas.org/kba-data (accessed on 11 September 2021).

- Boucher, J.; Brooks, M.; Cuttelod, A.; Dudley, N.; Langhammer, P.F. Applications of Key Biodiversity Areas: End-User Consultations; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Arriaga, L.; Vázquez-Dominguez, E.; González-Cano, J.; Jiménez-Rosenberg, R.; Muñoz-López, E.; Aguilar-Sierra, V. Regiones Marinas Prioritarias de México; Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y uso de la Biodiversidad: Ciudad de Mexico, Mexico, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Arriaga Cabrera, L.; Aguilar Sierra, V. Aguas Continentales y Diversidad Biológica de México; Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad: Ciudad de Mexico, Mexico, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- MAB—UNESCO. Biosphere Reserves in Latin America and the Caribbean. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/biosphere/lac (accessed on 11 September 2021).

- RAMSAR. Mexico|Ramsar. Available online: https://www.ramsar.org/wetland/mexico (accessed on 11 September 2021).

- Conabio-Conanp-TNC-Pronatura-FCF, UANL. Análisis de Vacios y Omisiones en Conservación de la Biodiversidad Terrestre de México: Espacios y Especies; Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León: México City, Mexico, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- CONABIO; CONANP; TNC; PRONATURA. Análisis de Vacíos y Omisiones en Conservación de la Biodiversidad Marina de México: Océanos, Costas e Islas; Pronatura, A.C., México, D.F., Eds.; The Nature Conservancy-Programa México: México City, Mexico, 2007; p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- RedParques, P.I.; México, P. Progreso de Cumplimiento de la Meta 11 de Aichi en los Países de la Redparques: Resultados y Perspectivas al 2020; CDB; Proyecto IAPA; Unión Europea; WWF; FAO; UICN; ONU Medio Ambiente: Bogotá, Colombia, 2018; Volume 46; Available online: https://www.portalces.org/sites/default/files/documentos/9._informe_meta_11_aichi_latinoamerica_low_.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2021).

| NPA | PTR | PHR | PMR | IBA | KBA | Ramsar | MAB-UNESCO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decree of creation | Problems | Problems | Problems | IBA Criteria met | KBA status | Associated with two PAs | |

| Management program | Conservation | Conservation | Conservation | Area | Global KBA criteria | ||

| Evaluation of Management Effectiveness | Proportion of the area under some form of adequate management | Groups and Institutions | Groups and Institutions | Protection status | Year of assessment | ||

| Importance of environmental services | Key biodiversity | National site name | |||||

| Presence of organized groups | Year of compilation | System | |||||

| Conservation policies | Pressure/threats to key biodiversity | Area of KBA (ha) | |||||

| Knowledge | IBA Protection | Protected area coverage (%) | |||||

| Information | IBA Criteria | Rationale for qualifying as KB | |||||

| Stage | National Scope | State Scope | Total of Interviewees |

|---|---|---|---|

| Planning and Coordination | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| Identification for designation | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Community members | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Users | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Total of interviewees | 4 | 9 | 13 |

| Level | Priority Regions AICAS/IBAs | Protected Natural Areas | Total of Interviewees |

|---|---|---|---|

| National | 4 | 4 | |

| State | 3 | 6 | 9 |

| Total | 7 | 6 | 13 |

| Sector | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public sector | x | x | x | x | 4 | |||||||||

| Non-governmental sector | x | x | x | 3 | ||||||||||

| Academic sector | x | x | 2 | |||||||||||

| Private sector | x | x | 2 | |||||||||||

| Community members | x | x | 2 |

| PA | Effectiveness Index | Context and Planning Index | Administrative and Financial Index | Usages and Benefit Index | Government and Social Practice Index | Handling Service | Total Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APFF Laguna Madre and Delta del Río Bravo | 61 Highly effective | 59 Partially effective | 55 Partially effective | 67 Highly effective | 74 Highly effective | 57 Partially effective | 74 Highly effective |

| Management Category | Name | Decree | Extension | MAB- UNESCO | MAB-UNESCO Evaluation | Ramsar | Ramsar Evaluation | Ramsar Last Published Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reserva de la Biosfera | El Cielo | State | 144 53051-00 | 1986 | 2002, 2013 | |||

| Santuario | Playa Tortuguera Rancho Nuevo | Federal | 90.65 | 2003 | N/A | 27 November 2003 | ||

| Área de Protección de Flora y Fauna | Laguna Madre y Delta Río Bravo | Federal | 572 808.6 | 2006 | No evaluation | 2004 | N/A | 2 February 2004 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Caballero-Rico, F.C.; Roque-Hernández, R.V.; de la Garza Cano, R.; Arvizu-Sánchez, E. Challenges for the Integrated Management of Priority Areas for Conservation in Tamaulipas, México. Sustainability 2022, 14, 494. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010494

Caballero-Rico FC, Roque-Hernández RV, de la Garza Cano R, Arvizu-Sánchez E. Challenges for the Integrated Management of Priority Areas for Conservation in Tamaulipas, México. Sustainability. 2022; 14(1):494. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010494

Chicago/Turabian StyleCaballero-Rico, Frida Carmina, Ramón Ventura Roque-Hernández, Ricardo de la Garza Cano, and Eduardo Arvizu-Sánchez. 2022. "Challenges for the Integrated Management of Priority Areas for Conservation in Tamaulipas, México" Sustainability 14, no. 1: 494. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010494

APA StyleCaballero-Rico, F. C., Roque-Hernández, R. V., de la Garza Cano, R., & Arvizu-Sánchez, E. (2022). Challenges for the Integrated Management of Priority Areas for Conservation in Tamaulipas, México. Sustainability, 14(1), 494. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010494