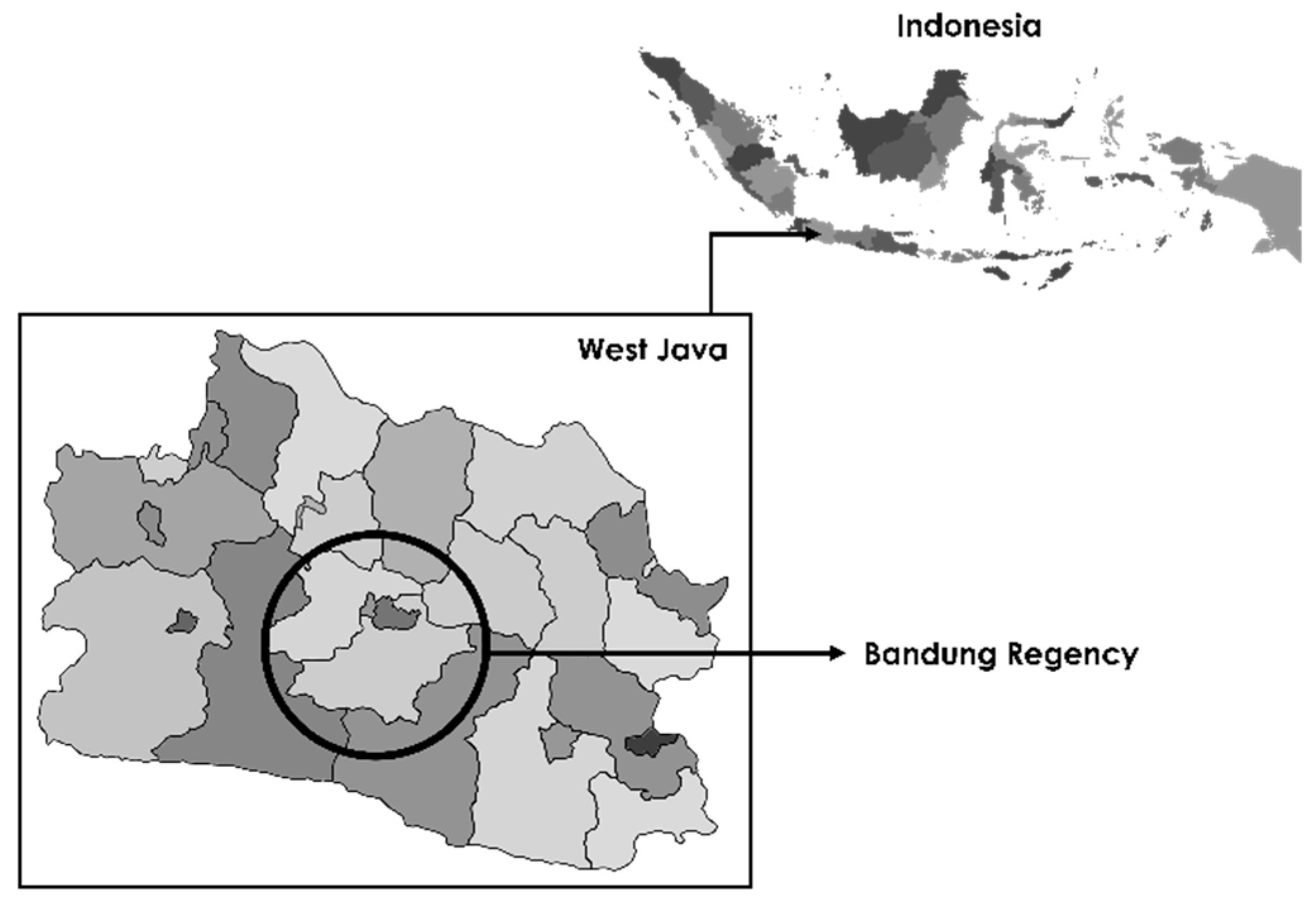

Co-Creation Approach in Designing a Sustainable Coffee Supply Chain (a Case in Bandung Regency, West Java, Indonesia)

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical Framework

1.1.1. Sustainable Food Supply Chain

1.1.2. Short Food Supply Chain for Sustainable Development

1.1.3. Co-Creation in Public Policy

2. Materials and Methods

The Action Research Process

3. Results

3.1. Existing Coffee Supply Chain

‘We are stuck in this situation, we know that the beans sell more than the cherries, but we do not know the standard quality of the beans asked by the market, we do not have the access to the technology, also most of us have no opportunity to do that because we have a deal with the middlemen even before the fruits are ready to be harvested’. Y (43),

‘Up to this day, it is hard for us to maintain the quality of our product, and our ability to meet the market demand. It is hard for us to make contract with our suppliers because we received green beans from different traders all the time. This affects our business and made it hard for us to expand’. JN (35),

3.2. The Role of the State

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Coffee Organization—Historical Data on the Global Coffee Trade. 2021. Available online: https://www.ico.org/new_historical.asp (accessed on 9 September 2021).

- Emlan, F.; Putra, W.E.; Ishak, A.; Astuti, H.B. Pendugaan Model Peramalan Harga Ekspor Kopi Indonesia. Agritepa J. Ilm. Dan Tek. Per. 2020, 7, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directorate General of Estate Crops. Statistical of National Leading Estate Crops Commodity. General Directorate of Estate Crops, Jakarta, Statistics. 2021. Available online: https://ditjenbun.pertanian.go.id/?publikasi=buku-statistik-perkebunan-2019-2021 (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Nugraha, A. An Ethnography Study of Farming Style in Gianyar, Bali, Indonesia; Wageningen University: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Booth, A. Indonesian agricultural development in comparative perspective. World Dev. 1989, 17, 1235–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuglie, K.O. Productivity growth in Indonesian agriculture, 1961–2000. Bull. Indones. Econ. Stud. 2004, 40, 209–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Booth, A. The performance of the Indonesian agricultural sector: Twelve questions and some tentative answers. In Land, Livelihood, the Economy and the Environment in Indonesia: Essays in Honour of Joan Hardjono; Yayasan Pustaka Obor Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2012; pp. 51–84. [Google Scholar]

- MacRae, G. Rice Farming in Bali: Organic Production and Marketing Challenges. Crit. Asian Stud. 2011, 43, 69–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geertz, C. Agricultural Involution; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gilman, N. Involution and modernization: The case of Clifford Geertz. Econ. Dev. Anthropol. Approach 2002, 19, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Lassa, J.A. Emerging ‘agricultural involution’ in Indonesia: Impact of natural hazards and climate extremes on agricultural crops and food system. In Economic and Welfare Impacts of Disasters in East Asia and Policy Responses; ERIA: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2012; pp. 601–640. [Google Scholar]

- McCullough, C. Review of ‘agricultural involution: The processes of ecological change in Indonesia’ by Clifford Geertz. Int. J. Anthropol. Ethnol. 2019, 3, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmato, D. Poverty and agricultural involution. In Some Aspects of Poverty in Ethiopia; Forum for Social Studies: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2003; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Maye, D.; Kirwan, J. Alternative Food Networks, Sociology of Agriculture and Food Entry for Sociopedia. isa. 2010. Available online: http://www.sagepub.net/isa/resources/pdf/AlternativeFood-Networks.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2021).

- Renting, H.; Marsden, T.K.; Banks, J. Understanding alternative food networks: Exploring the role of short food supply chains in rural development. Environ. Plan. A 2003, 35, 393–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashiri, M.; Tjahjono, B.; Lazell, J.; Ferreira, J.; Perdana, T. The Dynamics of Sustainability Risks in the Global Coffee Supply Chain: A Case of Indonesia–UK. Sustainability 2021, 13, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, C.R.; Rogers, D.S. A framework of sustainable supply chain management: Moving toward new theory. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2008, 38, 360–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seuring, S.; Müller, M. From a literature review to a conceptual framework for sustainable supply chain management. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1699–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilavanichakul, A.; Parthanadee, P. An Analysis of Sustainability Indicators on A Thai Arabica Coffee Value Chain. Panyapiwat J. 2019, 11, 139–154. [Google Scholar]

- Chiffoleau, Y.; Dourian, T. Sustainable food supply chains: Is shortening the answer? A literature review for a research and innovation agenda. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paciarotti, C.; Torregiani, F. The logistics of the short food supply chain: A literature review. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2020, 26, 428–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nsamzinshuti, A.; Janjevic, M.; Rigo, N.; Ndiaye, A.B. Logistics collaboration solutions to improve short food supply chain solution performance. In Proceedings of the 3rd World Conference on Supply Chain Management, Colombo, Sri Lanka, 17–19 May 2017; Volume 2, pp. 57–69. [Google Scholar]

- Blanquart, C.; Gonçalves, A.; Vandenbossche, L.; Kebir, L.; Petit, C.; Traversac, J.-B. The logistic leverages of short food supply chains performance in terms of sustainability. In Proceedings of the 12th World Conference on Transport Research, Lisboa, Portugal, 11–15 July 2010; 10p. [Google Scholar]

- Ilbery, B.; Maye, D. Food supply chains and sustainability: Evidence from specialist food producers in the Scottish/English borders. Land Use Policy 2005, 22, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebir, L.; Torre, A. Geographical proximity and new short supply food chains. In Creative Industries and Innovation in Europe; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 212–229. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, S.; Lobb, A.; Butler, L.; Harvey, K.; Traill, W.B. Local, national and imported foods: A qualitative study. Appetite 2007, 49, 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durham, C.A.; King, R.P.; Roheim, C.A. Consumer definitions of “Locally Grown” for fresh fruits and vegetables. J. Food Distrib. Res. 2009, 40, 56–62. [Google Scholar]

- Zepeda, L.; Leviten-Reid, C. Consumers’ views on local food. J. Food Distrib. Res. 2004, 35, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Engelseth, P.; Hogset, H. Adapting supply chain management for local foods logistics. Proc. Food Syst. Dyn. 2015, 8, 111–119. [Google Scholar]

- Marsden, T.; Banks, J.; Bristow, G. Food supply chain approaches: Exploring their role in rural development. Sociol. Rural. 2000, 40, 424–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneafsey, M.; Venn, L.; Schmutz, U.; Balázs, B.; Trenchard, L.; Eyden-Wood, T.; Bos, E.; Sutton, G.; Blackett, M. Short food supply chains and local food systems in the EU. A state of play of their socio-economic characteristics. JRC Sci. Policy Rep. 2013, 123, 129. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, G. Sustainable Food? Teikei, Co-Operatives and Food Citizenship in Japan and the UK. 2005. Available online: https://centaur.reading.ac.uk/21289/ (accessed on 26 October 2021).

- Galli, F.; Brunori, G. Short Food Supply Chains as Drivers of Sustainable Development. Evidence Document. 2013. Available online: https://orgprints.org/id/eprint/28858/1/evidence-document-sfsc-cop.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Voorberg, W.H.; Bekkers, V.J.; Tummers, L.G. A systematic review of co-creation and co-production: Embarking on the social innovation journey. Public Manag. Rev. 2015, 17, 1333–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voorberg, W.; Bekkers, V.; Flemig, S.; Timeus, K.; Tonurist, P.; Tummers, L. Does co-creation impact public service delivery? The importance of state and governance traditions. Public Money Manag. 2017, 37, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alford, J. Engaging Public Sector Clients: From Service-Delivery to Co-Production; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bason, C.; Bourgon, J. Leading Public Sector Innovation; Bristol University Press: Bristol, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Parrado, S.; van Ryzin, G.G.; Bovaird, T.; Löffler, E. Correlates of co-production: Evidence from a five-nation survey of citizens. Int. Public Manag. J. 2013, 16, 85–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Ari, E. A bureaucrat in every Japanese kitchen? On cultural assumptions and coproduction. Adm. Soc. 1990, 21, 472–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wipf, E.; Ohl, F.; Groeneveld, M. Managing natural Locations For Outdoor Recreation: The role of consultative procedures and the sense of justice. Public Manag. Rev. 2009, 11, 515–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, U. The multiplex city: The process of urban change in the historic centre of Naples. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2004, 11, 156–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reason, P.; Bradbury, H. Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Denis, J.-L.; Lehoux, P.; Hivon, M.; Champagne, F. Creating a new articulation between research and practice through policy? The views and experiences of researchers and practitioners. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2003, 8, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, B.; Sankaran, S.; Shaw, K.; Kelly, J.; Soar, J.; Davies, A.; Banbury, A. Value co-creation with stakeholders using action research as a meta-methodology in a funded research project. Proj. Manag. J. 2015, 46, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edson, M.C. A complex adaptive systems view of resilience in a project team. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2012, 29, 499–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, K. Action research and minority problems. J. Soc. Issues 1946, 2, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susman, G.I.; Evered, R.D. An assessment of the scientific merits of action research. Adm. Sci. Q. 1978, 582–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McTaggart, R. Guiding principles for participatory action research. Particip. Action Res. Int. Contexts Conseq. 1997, 25–43. [Google Scholar]

- Deming, W.E. Out of the Crisis; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. Developmental Evaluation: Applying Complexity Concepts to Enhance Innovation and Use; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kolb, D.A. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development; FT Press: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Loughlin, J.; Peters, B.G. State Traditions, Administrative Reform and Regionalization. In The Political Economy of Regionalism; Keating, M., Loughlin, J., Eds.; Frank Cass: London, UK, 1997; pp. 41–62. [Google Scholar]

- Aguiar, L.d.C.; DelGrossi, M.E.; Thomé, K.M. Short food supply chain: Characteristics of a family farm. Ciênc. Rural 2018, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canfora, I. Is the short food supply chain an efficient solution for sustainability in food market? Agric. Agric. Sci. Procedia 2016, 8, 402–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbrizzi, S.; Menghini, S.; Marinelli, N. The short food supply chain: A concrete example of sustainability. A literature review. Riv. Di Studi Sulla Sostenibilita 2014, 2, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.; Lawrence, G.; MacMahon, A.; Muller, J.; Brady, M. The resilience of long and short food chains: A case study of flooding in Queensland, Australia. Agric. Hum. Values 2016, 33, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, J. Social Entrepreneurship: Taking Stock and Looking ahead. 2010. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1729642 (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Mulgan, G. The Art of Public Strategy: Mobilizing Power and Knowledge for the Common Good; Oxford University Press on Demand; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne, S.P.; Brown, L. Innovation in public services: Engaging with risk. Public Money Manag. 2011, 31, 4–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, S.P. The New Public Governance? 1; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Stoker, G. Public value management: A new narrative for networked governance? Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2006, 36, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component | Brief Description | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Focus Group 1 | Identifying the current problems on the coffee supply chain from actors’ perspective | Brief introduction to the theme of the study Creating common grounds with the actors Enhancing communications and collaborations among the actors Problem identifications by actors including farmers, suppliers, intermediaries, cooperatives, academicians, government agents to grasp their understanding of the current situation |

| Workshop 1 | Scenario planning to define possible futures Half-day workshop | Multiple scenarios so that problems identified are likely to be relevant |

| Workshop 2 | To generate solutions based on actors’ perspective Half-day workshop | Study purpose was to define solutions by actors in coffee supply chain |

| Interviews | 15 in-depth interviews | To triangulate findings from workshops |

| Framework | Research team collected material from workshops and interviews | To convert data into an actionable policy framework |

| Focus Group 2 | One focus group with key informants Participants defined a vision for their sustainable coffee supply chain and identified present problems and the solutions | To extend results beyond the single coffee supply chain of the pilot study For participants to identify desirable future coffee supply chain while remaining anchored to some extent to the reality of their present situation |

| Survey | Survey of a stratified random sample of farmers | To triangulate the focus group results |

| Scenario-based workshops | In small groups (two for each group) participants considered a likely near-future scenario as realistic and challenging for identify required solutions | To collect more information To triangulate with data from pilot study and the components of the main study To collect data on differences between their supply chain, and other cases To augment the first survey |

| Framework check | As part of each scenario-based workshop (above), participants were asked to comment on the adequacy, usefulness, and completeness of the framework developed in the pilot study | To further refine the framework. To test it against the perceptions of managers from the industry partners after they had been reflecting on required capabilities |

| Actors | n | Satisfied | Neutral | Not Satisfied |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smallholder Farmers | 80 | n = 8 (10%) | n = 16 (20%) | n = 56 (70%) |

| Medium Farmers | 80 | n = 12 (15%) | n = 12 (15%) | n = 56 (70%) |

| Large Farmers | 80 | n = 16 (20%) | n = 24 (30%) | n = 40 (50%) |

| Middlemen | 25 | n = 15 60% | n = 7 28% | n = 3 12% |

| Processor | 10 | n = 4 40% | n = 2 20% | n = 4 40% |

| Retailer | 5 | n = 3 60% | n = 1 20% | n = 1 20% |

| Sustainability Problems | Farmers | Processing Units | Traders (incl. Middlemen) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Economic (incl. production and marketing) | Limited market share Limited value gained No local exporters Low cherry price High production costs Low capital Dependency on the middlemen Low technology Limited knowledge and skills | Unstandardized product quality Unpredicted product availability Low equipment and machine capacity Volatile product price Low capital | Volatile product price Low capital Unstandardized product quality Unpredicted product availability |

| Social | Dependency on the middlemen | Unorganized middlemen | Low commitment from the farmers Unhealthy competition |

| Environmental | Polluted farm Soil degradation Unpredictable season Changing agroecosystem | Low quality product due to environmental degradation | Low quality product due to environmental degradation Long traveling time and range to reach each plantation |

| Problems | Solutions | Implementation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Farmers | Traders (incl. Middlemen) | ||

| Economic | Collective farming to improve efficiency Collective post-harvest management to improve product quality Collective marketing to improve bargaining position | Involvement in quality control to disseminate market information for the required standard quality Collective trading to improve capital and marketing | Most of these activities involves collective actions which need to be organized in a cooperative |

| Social | Joint training with experienced farmers Access to market information (price and quality) | Involvement in quality control to disseminate market information for the required standard quality | |

| Environmental | Collective farming to control the application of GAP | ||

| Sustainability Element | Farmers | Traders (incl. Middlemen) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rights | Duties | Rights | Duties | |

| Economic (production, marketing) | Access to credit from the cooperative Access to affordable quality agro-inputs Market price information | Focuses on coffee cultivation Improve product quality and quantity Pay debts Ensure supply continuity | Access to Credit from the cooperative | Provide market information (desired quality and price) Transparency in buying price |

| Social | Trainings and guidance for Good Agricultural Practices Trainings on certified nursery | Join trainings and disseminate gained knowledge Farm collectively | Information of planting schedule Trainings and guidance | Disseminate knowledge |

| Environmental | Trainings and guidance for environmentally friendly agricultural practices | Apply Good Agricultural Practices Improve agroecosystem through multi-cropping | Access to product distribution centre as their pick-up point | Create a distribution centre with the most effective and accessible location for all traders and farmers to cut range |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Umaran, T.; Perdana, T.; Kurniadie, D.; Parikesit, P. Co-Creation Approach in Designing a Sustainable Coffee Supply Chain (a Case in Bandung Regency, West Java, Indonesia). Sustainability 2022, 14, 476. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010476

Umaran T, Perdana T, Kurniadie D, Parikesit P. Co-Creation Approach in Designing a Sustainable Coffee Supply Chain (a Case in Bandung Regency, West Java, Indonesia). Sustainability. 2022; 14(1):476. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010476

Chicago/Turabian StyleUmaran, Tisna, Tomy Perdana, Denny Kurniadie, and Parikesit Parikesit. 2022. "Co-Creation Approach in Designing a Sustainable Coffee Supply Chain (a Case in Bandung Regency, West Java, Indonesia)" Sustainability 14, no. 1: 476. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010476

APA StyleUmaran, T., Perdana, T., Kurniadie, D., & Parikesit, P. (2022). Co-Creation Approach in Designing a Sustainable Coffee Supply Chain (a Case in Bandung Regency, West Java, Indonesia). Sustainability, 14(1), 476. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010476