Consumer Ethnocentrism and Country of Origin: Effects on Online Consumer Purchase Behavior in Times of a Pandemic

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Conceptual Framework and Research Model

2.1. Consumer Ethnocentrism

2.2. Country of Origin

2.3. Theory of Planned Behavior

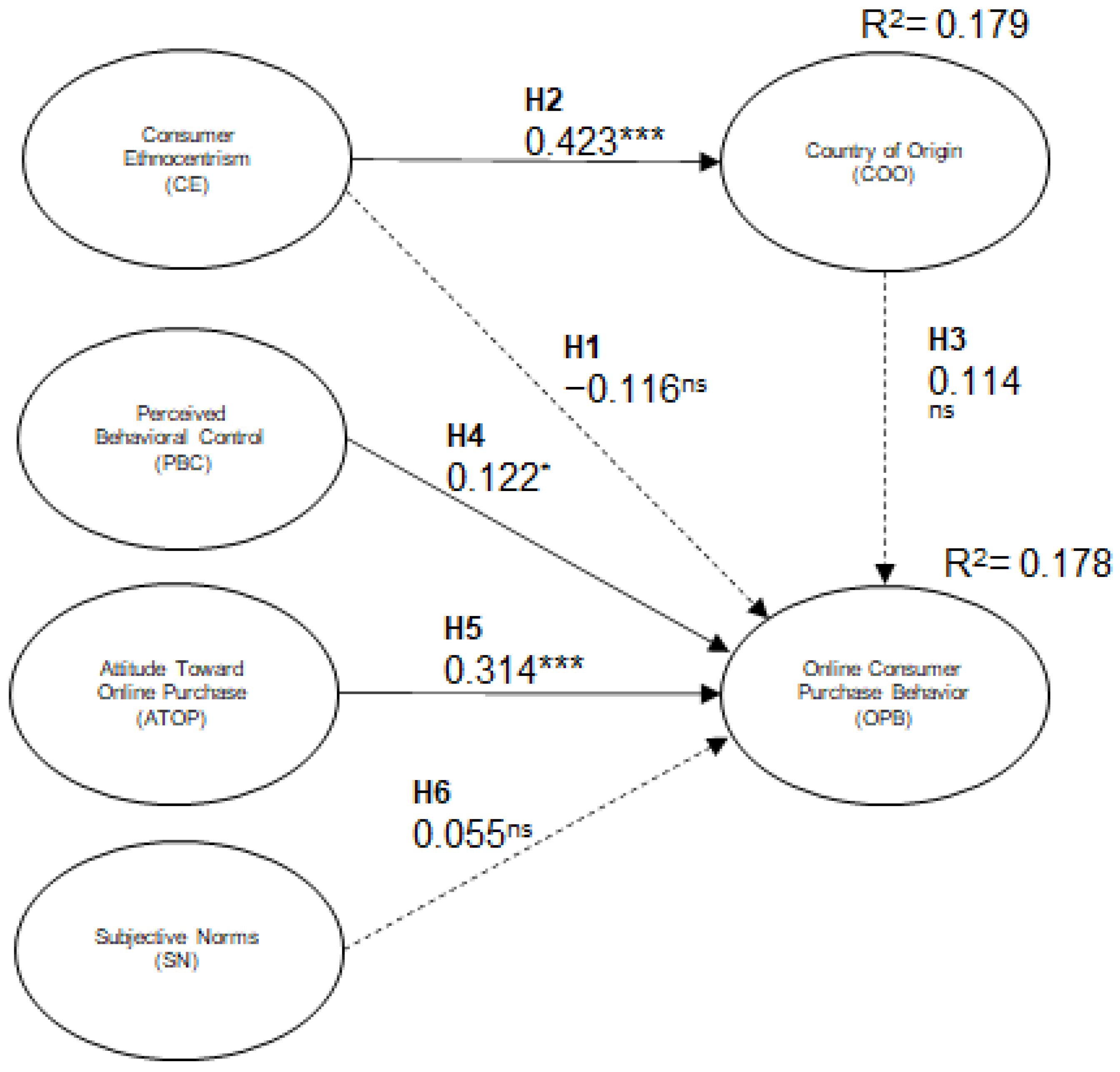

2.4. Research Model

3. Materials and Methods

4. Analysis and Results

4.1. Measurement Model

4.2. Structural Model

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Managerial Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Latent Variable/Item | Scale |

|---|---|

| Attitude Toward Online Purchase (ATOP) | |

| Buying things online is a. | Very bad idea—Very good idea |

| Buying things online is a. | Very silly idea—Very intelligent idea |

| Buying things online is an idea that I. | Dislike a lot—I like too much |

| Using the Internet to buy things would be. | Very unpleasant—Very pleasant |

| Subjective Norms (SN) | |

| People who influence my behavior would think I should buy things online. | Strongly disagree—Strongly agree |

| People who are important to me would think I should buy things online. | Strongly disagree—Strongly agree |

| Perceived behavioral control (PBC) | |

| I’m able to buy things online. | Strongly disagree—Strongly agree |

| Buying things online is completely under my control. | Strongly disagree—Strongly agree |

| I have the resources, the knowledge and the ability to buy things online. | Strongly disagree—Strongly agree |

| Online shopping behavior (OPB) | |

| How much would I say you spend on online shopping each month? | Nothing to 250 dollars |

| Consumer Ethnocentrism (CE) | |

| We should always buy local products instead of imports. | Strongly disagree—Strongly agree |

| Only products that are not available in our country should be imported. | Strongly disagree—Strongly agree |

| Buying our domestic products keeps our people working. | Strongly disagree—Strongly agree |

| Local products, from the first to the last, are always the most important. | Strongly disagree—Strongly agree |

| Buying foreign products is anti-Colombian. | Strongly disagree—Strongly agree |

| It is not right to buy foreign products. | Strongly disagree—Strongly agree |

| An authentic Colombian should buy products made in Colombia. | Strongly disagree—Strongly agree |

| We should buy products manufactured in Colombia instead of making other countries rich at our expense. | Strongly disagree—Strongly agree |

| It is always better to buy Colombian products. | Strongly disagree—Strongly agree |

| There should be little marketing of products from other countries unless it is a necessity. | Strongly disagree—Strongly agree |

| Colombians should not buy foreign products because they damage Colombian businesses and cause unemployment. | Strongly disagree—Strongly agree |

| Restrictions should be placed on all imports. | Strongly disagree—Strongly agree |

| It could cost me more in the long run, but I prefer to support Colombian products. | Strongly disagree—Strongly agree |

| Foreigners should not be allowed to place their products in our markets. | Strongly disagree—Strongly agree |

| Foreign products should be taxed highly to reduce their entry into Colombia. | Strongly disagree—Strongly agree |

| We should buy foreign products only if these products cannot be obtained within our country. | Strongly disagree—Strongly agree |

| Colombian consumers who buy imported products are responsible for putting their compatriots out of work. | Strongly disagree—Strongly agree |

| Country of Origin (COO) | |

| When buying imported products, the country of origin is the information I take into consideration. | Strongly disagree—Strongly agree |

| I look for the information of the country of origin to select the best imported product available in the market. | Strongly disagree—Strongly agree |

| I understand that the country of origin determines the quality of the imported products. | Strongly disagree—Strongly agree |

| When I buy expensive imported products, I always look for which country it was manufactured in. | Strongly disagree—Strongly agree |

| If I have little experience in the type of imported product, I look for the information of the country of origin to help me make a better decision. | Strongly disagree—Strongly agree |

References

- Schmid, S.; Kotulla, T. 50 years of research on international standardization and adaptation—From a systematic literature analysis to a theoretical framework. Int. Bus. Rev. 2011, 20, 491–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandler, T.; Sezen, B.; Chen, J.; Özsomer, A. Performance consequences of marketing standardization/adaptation: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 125, 416–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, J.; Moore, M.; Doherty, A.M.; Alexander, N. Acculturation to the global consumer culture: A generational cohort comparison. J. Strat. Mark. 2012, 20, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Woodside, A.G.; Hsu, S.-Y.; Marshall, R. General theory of cultures’ consequences on international tourism behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2011, 64, 785–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pharr, J.M. Synthesizing Country-of-Origin Research from the Last Decade: Is the Concept Still Salient in an Era of Global Brands? J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2005, 13, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tate, W.L.; Ellram, L.M.; Schoenherr, T.; Petersen, K.J. Global competitive conditions driving the manufacturing location decision. Bus. Horiz. 2014, 57, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, L.N.K.; Jones, K. Consumer-to-Consumer Ecommerce: Acceptance and Intended Behavior. Commun. IIMA 2014, 14, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Maciaszczyk, M.; Kocot, M. Behavior of Online Prosumers in Organic Product Market as Determinant of Sustainable Consumption. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Qu, Y.; Lei, Z.; Jia, H. Understanding the Evolution of Sustainable Consumption Research. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 25, 414–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, R.W. Fundamentals of Management; Cengage: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Review of the EU Sustainable Development Strategy—Renewed Strategy. Available online: https://www.etuc.org/en/revieweu-sustainable-development-strategy (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Sustainable Consumption Helping Consumers Make Eco-Friendly Choices. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2020/659295/EPRS_BRI(2020)659295_EN.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Abedniya, A.; Zaeim, M.N. The impact of country of origin and ethnocentrism as major dimensions in consumer purchasing behavior in fashion industry. Eur. J. Econ. Financ. Adm. Sci. 2011, 33, 222–232. [Google Scholar]

- Camacho, L.J.; Salazar-Concha, C.; Ramírez-Correa, P. The Influence of Xenocentrism on Purchase Intentions of the Consumer: The Mediating Role of Product Attitudes. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Swaminathan, V.; Page, K.L.; Gürhan-Canli, Z. “My” brand or “our” brand: The effects of brand relationship dimensions and self-construal on brand evaluations. J. Consum. Res. 2007, 34, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wanninayake, W.M.C.B.; Chovancova, M. Consumer Ethnocentrism and Attitudes towards Foreign Beer Brands: With Evidence from Zlin Region in the Czech Republic. J. Compet. 2012, 4, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oláh, J.; Kitukutha, N.; Haddad, H.; Pakurár, M.; Máté, D.; Popp, J. Achieving Sustainable E-Commerce in Environmental, Social and Economic Dimensions by Taking Possible Trade-Offs. Sustainability 2019, 11, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pei, X.-L.; Guo, J.-N.; Wu, T.-J.; Zhou, W.-X.; Yeh, S.-P. Does the Effect of Customer Experience on Customer Satisfaction Create a Sustainable Competitive Advantage? A Comparative Study of Different Shopping Situations. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.K.; Duarte, P.; Silva, S.C.; Zhuang, G. Supporting sustainability by promoting online purchase through enhancement of online convenience. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 7251–7272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Wang, C.L. Cultural identity and consumer ethnocentrism impacts on preference and purchase of domestic versus import brands: An empirical study in China. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1225–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdogan, M.S.; Ozgener, S.; Kaplan, M.; Coskun, A. The effects of consumer ethnocentrism and consumer animosity on the re-purchase intent: The moderating role of consumer loyalty. EMAJ: Emerg. Mark. J. 2012, 2, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pentz, C.; Terblanche, N.S.; Boshoff, C. Measuring Consumer Ethnocentrism in a Developing Context: An Assessment of the Reliability, Validity and Dimensionality of the CETSCALE. J. Transnatl. Manag. 2013, 18, 204–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godey, B.; Pederzoli, D.; Aiello, G.; Donvito, R.; Chan, P.; Oh, H.; Singh, R.; Skorobogatykh, I.; Tsuchiya, J.; Weitz, B. Brand and country-of-origin effect on consumers’ decision to purchase luxury products. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1461–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montanari, M.G.; Rodrigues, J.M.; Giraldi, J.D.M.E.; Neves, M.F. Country of origin effect: A study with Brazilian consumers in the luxury market. Braz. Bus. Rev. 2018, 15, 348–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, S.; Wamba, S.F.; Dewan, S. Why PLS-SEM is suitable for complex modelling? An empirical illustration in big data analytics quality. Prod. Plan. Control. 2017, 28, 1011–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. In Advances in International Marketing; Sinkovics, R.R., Ghauri, P.N., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bradford, UK, 2009; pp. 277–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shimp, T.A.; Sharma, S. Consumer Ethnocentrism: Construction and Validation of the CETSCALE. J. Mark. Res. 1987, 24, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sharma, P. Consumer ethnocentrism: Reconceptualization and cross-cultural validation. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2015, 46, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Keillor, B.D.; Parker, R.S.; Schaefer, A. Influences on adolescent brand preferences in the United States and Mexico. J. Advert. Res. 1996, 36, 47–57. [Google Scholar]

- Alden, D.L.; Kelley, J.B.; Riefler, P.; Lee, J.A.; Soutar, G.N. The Effect of Global Company Animosity on Global Brand Attitudes in Emerging and Developed Markets: Does Perceived Value Matter? J. Int. Mark. 2013, 21, 17–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surdu, I.; Mellahi, K.; Glaister, K.W. Once bitten, not necessarily shy? Determinants of foreign market re-entry commitment strategies. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2018, 50, 393–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnusson, P.; Krishnan, V.; Westjohn, S.A.; Zdravkovic, S. The Spillover Effects of Prototype Brand Transgressions on Country Image and Related Brands. J. Int. Mark. 2014, 22, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Balabanis, G.; Siamagka, N.T. Inconsistencies in the behavioural effects of consumer ethnocentrism: The role of brand, product category and country of origin. Int. Mark. Rev. 2017, 34, 166–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. The Social Identity Theory of Intergroup Behavior. In Political Psychology: Key Readings; Jost, J., Sidanius, J., Eds.; Psychology Press: East Sussex, UK, 2004; pp. 276–293. [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland, M.; Balakrishnan, A. Appreciating vs venerating cultural outgroups: The psychology of cosmopolitanism and xenocentrism. Int. Mark. Rev. 2019, 36, 416–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, J.L.; Nien, H.-P. Who are ethnocentric? Examining consumer ethnocentrism in Chinese societies. J. Consum. Behav. 2008, 7, 436–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balabanis, G.; Diamantopoulos, A.; Mueller, R.D.; Melewar, T.C. The Impact of Nationalism, Patriotism and Internationalism on Consumer Ethnocentric Tendencies. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2001, 32, 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, P. The Meaning of ‘Race’ and ‘Ethnicity’. In Race and Ethnicity in Latin America; Pluto Press: London, UK, 2010; pp. 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumner, W.G. Folkways, a Study of the Sociological Importance of Usages, Manners, Customs, Mores and Morals. Am. J. Psychol. 1907, 18, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schooler, R.D. Product Bias in the Central American Common Market. J. Mark. Res. 1965, 2, 394–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyczek, S.; Glowik, M. Ethnocentrism of Polish consumers as a result of the global economic crisis. J. Cust. Behav. 2011, 10, 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, J.G.; Ettenson, R.; Morris, M.D. The animosity model of foreign product purchase: An empirical test in the People’s Republic of China. J. Mark. 1998, 62, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Pysarchik, D.T. Predicting purchase intentions for uni-national and bi-national products. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2000, 28, 280–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.-J.; Nelson, M.R. Exploring the influence of media exposure and cultural values on Korean immigrants’ advertising evaluations. Int. J. Advert. 2008, 27, 299–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maksan, M.T.; Kovačić, D.; Cerjak, M. The influence of consumer ethnocentrism on purchase of domestic wine: Application of the extended theory of planned behaviour. Appetite 2019, 142, 104393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hien, N.N.; Phuong, N.N.; Van Tran, T.; Thang, L.D. The effect of country-of-origin image on purchase intention: The mediating role of brand image and brand evaluation. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2020, 10, 1205–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezvani, S.; Dehkordi, G.J.; Rahman, M.S.; Fouladivanda, F.; Habibi, M.; Eghtebasi, S. A Conceptual Study on the Country of Origin Effect on Consumer Purchase Intention. Asian Soc. Sci. 2012, 8, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johansson, J.K.; Douglas, S.P.; Nonaka, I. Assessing the Impact of Country of Origin on Product Evaluations: A New Methodological Perspective. J. Mark. Res. 1985, 22, 388–396. [Google Scholar]

- Insch, G.S.; McBride, J.B. The impact of country-of-origin cues on consumer perceptions of product quality: A binational test of the decomposed country-of-origin construct. J. Bus. Res. 2004, 57, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.M.; Terpstra, V. Country-of-Origin Effects for Uni-National and Bi-National Products. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1988, 19, 235–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.K.; Lamb, C.W. The impact of selected environmental forces upon consumers’ willingness to buy foreign products. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1983, 11, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usunier, J.-C.; Cestre, G. Product Ethnicity: Revisiting the Match between Products and Countries. J. Int. Mark. 2007, 15, 32–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verlegh, P.W.J.; Steenkamp, J.B.E.M.; Meulenberg, M.T.G. Country-of-origin effects in consumer processing of advertising claims. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2005, 22, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, J.G.; Holdsworth, D.K.; Mather, D. Country-of-origin and choice of food imports: An in-depth study of European distribution channel gatekeepers. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2007, 38, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insch, A.; Williams, S.; Knight, J.G. Managerial Perceptions of Country-of-Origin: An Empirical Study of New Zealand Food Manufacturers. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2015, 22, 304–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekhili, S.; D’Hauteville, F. Effect of the region of origin on the perceived quality of olive oil: An experimental approach using a control group. Food Qual. Prefer. 2009, 20, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, M.L.; Umberger, W.J. A choice experiment model for beef: What US consumer responses tell us about relative preferences for food safety, country-of-origin labeling and traceability. Food Policy 2007, 32, 496–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, C.; Boyer, T.; Han, S. Valuing Quality Attributes and Country of Origin in the Korean Beef Market. J. Agric. Econ. 2009, 60, 682–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukasovič, T. European meat market trends and consumer preference for poultry meat in buying decision making process. World’s Poult. Sci. J. 2014, 70, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, K.; Insch, A.; Holdsworth, D.K.; Knight, J.G. Food miles: Do UK consumers actually care? Food Policy 2010, 35, 504–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeke, W.; Ward, R.W. Consumer interest in information cues denoting quality, traceability and origin: An application of ordered probit models to beef labels. Food Qual. Prefer. 2006, 17, 453–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, C.K.; Eskridge, K.M.; Calkins, C.R.; Umberger, W.J. Assessing consumer preferences for rib-eye steak characteristics using confounded factorial conjoint choice experiments. J. Muscle Foods 2010, 21, 224–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unahanandh, S.; Assarut, N. Dairy Products Market Segmentation: The Effects of Country of Origin on Price Premium and Purchase Intention. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2013, 25, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dursun, I.; Kabadayi, E.T.; Ceylan, K.E.; Köksal, C.G. Russian Consumers Responses to Turkish Products: Exploring the Roles of Country Image, Consumer Ethnocentrism, and Animosity. Bus. Econ. Res. J. 2019, 10, 499–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Díaz, L. Destination Image in the COVID-19 Crisis: How to Mitigate the Effect of Negative Emotions, Developing Tourism Strategies for Ethnocentric and Cosmopolitan Consumers. Multidiscip. Bus. Rev. 2021, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-J. The Impact of Consumer Competence in Purchasing Foods on Satisfaction with Food-Related Consumer Policies and Satisfaction with Food-Related Life through Perceptions of Food Safety. Foods 2020, 9, 1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha-Brookshire, J.; Yoon, S.-H. Country of origin factors influencing US consumers’ perceived price for multinational products. J. Consum. Mark. 2012, 29, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augusta, E.D.; Mardhiyah, D.; Widiastuti, T. Effect of country of origin image, product knowledge, brand familiarity to purchase intention Korean cosmetics with information seeking as a mediator variable: Indonesian women’s perspective. Dermatol. Rep. 2019, 11, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.V.; Tran, K.T.; Le, H.M.P.T. Effects of country of origin, foreign product knowledge and product features on customer purchase intention of imported powder milk. Int. J. Bus. Innov. Res. 2019, 19, 139–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In Action Control: From Cognition to Behavior; Kuhl, J., Beckman, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 1985; pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behaviour: Reactions and reflections. Psychol. Health 2011, 26, 1113–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. On the Functional Properties of Perceived Self-Efficacy Revisited. J. Manag. 2011, 38, 9–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. Am. Psychol. 1982, 37, 122–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, K.-P.; Jackson, A. Consumer vulnerability in the context of direct-to-consumer prescription drug. Int. J. Healthc. Manag. 2012, 5, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, S.; Wu, Y. Using the Theory of Planned Behaviour to explain customers’ online purchase intention. World Sci. Res. J. 2019, 5, 226–249. [Google Scholar]

- George, J. The theory of planned behavior and Internet purchasing. Internet Res. 2004, 14, 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dezdar, S. Green information technology adoption: Influencing factors and extension of theory of planned behavior. Soc. Responsib. J. 2017, 13, 292–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangwal, N.; Bansal, V. Application of Decomposed Theory of Planned Behavior for M-commerce Adoption in India. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems, ICEIS 2016, Rome, Italy, 25–28 April 2016; pp. 357–367. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, L.M.; Shiu, E.; Parry, S. Addressing the cross-country applicability of the theory of planned behaviour (TPB): A structured review of multi-country TPB studies. J. Consum. Behav. 2015, 15, 72–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redda, E.H. Attitudes towards online shopping: Application of the theory of planned behaviour. Acta Univ. Danubius. Acon. 2019, 2, 148–159. [Google Scholar]

- Yaghoubi, N.-M.; Bahmani, E. Factors affecting the adoption of online banking: An integration of technology acceptance model and theory of planned behavior. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2010, 9, 159–165. [Google Scholar]

- Migliore, G.; Rizzo, G.; Schifani, G.; Quatrosi, G.; Vetri, L.; Testa, R. Ethnocentrism Effects on Consumers’ Behavior during COVID-19 Pandemic. Economies 2021, 9, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh, V.; Thong, J.Y.L.; Xu, X. Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: Extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS Q. 2012, 36, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Demographic Variable | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 164 | 51.7 |

| Male | 153 | 48.3 |

| Age | ||

| 18–24 | 92 | 31.3 |

| 25–34 | 49 | 16.7 |

| 35–44 | 54 | 18.4 |

| 45–54 | 70 | 23.8 |

| 55–64 | 26 | 8.8 |

| 65+ | 3 | 1.0 |

| Education | ||

| High School Degree or equivalent | 14 | 4.8 |

| Some college but no degree | 89 | 30.2 |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 76 | 25.9 |

| Some Graduate Study but no degree | 27 | 9.2 |

| Graduate | 88 | 29.9 |

| Latent Variables | Value |

|---|---|

| Attitude Toward Online Purchase (ATOP) | |

| Cronbach’s Alpha | 0.907 |

| Composite Reliability | 0.935 |

| AVE | 0.782 |

| ATOP1 | 0.907 |

| ATOP2 | 0.856 |

| ATOP3 | 0.898 |

| ATOP4 | 0.877 |

| Subjective Norms (SN) | |

| Cronbach’s Alpha | 0.754 |

| Composite Reliability | 0.835 |

| AVE | 0.724 |

| SN1 | 0.676 |

| SN2 | 0.996 |

| Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC) | |

| Cronbach’s Alpha | 0.723 |

| Composite Reliability | 0.870 |

| AVE | 0.771 |

| PBC1 | 0.806 |

| PBC2 | 0.944 |

| Consumer Ethnocentrism (CE) | |

| Cronbach’s Alpha | 0.933 |

| Composite Reliability | 0.942 |

| AVE | 0.599 |

| CE1 | 0.743 |

| CE2 | 0.754 |

| CE3 | 0.744 |

| CE4 | 0.730 |

| CE5 | 0.807 |

| CE6 | 0.851 |

| CE7 | 0.738 |

| CE8 | 0.829 |

| CE9 | 0.754 |

| CE10 | 0.725 |

| CE11 | 0.825 |

| Country of Origin (COO) | |

| Cronbach’s Alpha | 0.862 |

| Composite Reliability | 0.900 |

| AVE | 0.644 |

| COO1 | 0.785 |

| COO2 | 0.838 |

| COO3 | 0.747 |

| COO4 | 0.831 |

| COO5 | 0.808 |

| Latent Variable | ATOP | PBC | CE | COO | SN | OPB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fornell–Larcker criterion | ||||||

| ATOP | 0.884 | |||||

| PBC | 0.365 | 0.878 | ||||

| CE | −0.080 | −0.178 | 0.774 | |||

| COO | −0.047 | −0.020 | 0.423 | 0.802 | ||

| SN | 0.268 | 0.143 | −0.023 | −0.005 | 0.851 | |

| OPB | 0.378 | 0.263 | −0.116 | 0.047 | 0.159 | |

| Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) | ||||||

| PBC | 0.452 | |||||

| CE | 0.092 | 0.217 | ||||

| COO | 0.057 | 0.062 | 0.456 | |||

| SN | 0.287 | 0.224 | 0.082 | 0.070 | ||

| OPB | 0.393 | 0.289 | 0.133 | 0.063 | 0.122 | |

| Relationships/Indexes | Global |

|---|---|

| H1: CE ➔ OPB | −0.116 ns |

| H2: CE ➔ COO | 0.423 *** |

| H3: COO ➔ OPB | 0.114 ns |

| H4: PBC ➔ OPB | 0.122 * |

| H5: ATOP ➔ OPB | 0.314 *** |

| H6: SN ➔ OPB | 0.055 ns |

| R2 of OPB | 0.178 |

| R2 Adjusted of OPB | 0.164 |

| Q2 Predict of OPB | 0.142 |

| R2 of COO | 0.179 |

| R2 Adjusted of COO | 0.176 |

| Q2 Predict of COO | 0.168 |

| SRMR | 0.058 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Camacho, L.J.; Ramírez-Correa, P.E.; Salazar-Concha, C. Consumer Ethnocentrism and Country of Origin: Effects on Online Consumer Purchase Behavior in Times of a Pandemic. Sustainability 2022, 14, 348. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010348

Camacho LJ, Ramírez-Correa PE, Salazar-Concha C. Consumer Ethnocentrism and Country of Origin: Effects on Online Consumer Purchase Behavior in Times of a Pandemic. Sustainability. 2022; 14(1):348. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010348

Chicago/Turabian StyleCamacho, Luis José, Patricio Esteban Ramírez-Correa, and Cristian Salazar-Concha. 2022. "Consumer Ethnocentrism and Country of Origin: Effects on Online Consumer Purchase Behavior in Times of a Pandemic" Sustainability 14, no. 1: 348. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010348

APA StyleCamacho, L. J., Ramírez-Correa, P. E., & Salazar-Concha, C. (2022). Consumer Ethnocentrism and Country of Origin: Effects on Online Consumer Purchase Behavior in Times of a Pandemic. Sustainability, 14(1), 348. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010348