The Impact of Sustainability and Leadership on the Innovation Management of Michelin-Starred Chefs

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainabilty

2.2. Leadership

2.3. Innovation

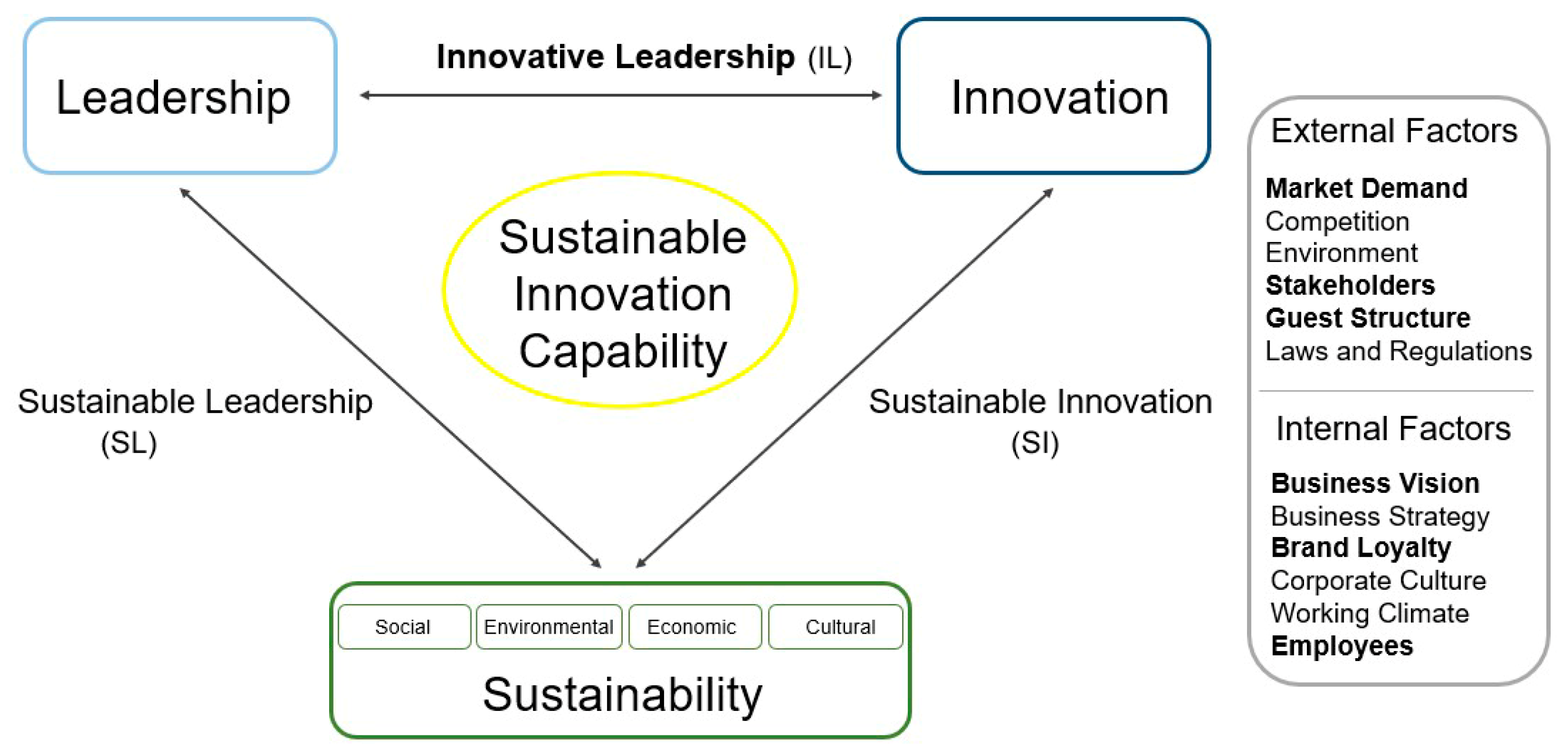

2.4. The Linkage between Sustainability, Leadership and Innovation

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Validity and Reliability

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Sustainability in Michelin-Starred Restaurants

4.2. Leadership in Michelin-Starred Restaurants

4.3. Innovation in Michelin-Starred Restaurants

4.4. The Linkage between Sustainabilty, Leadership and Innovation in Michelin-Starred Restaurants

5. Discussion

6. Implications

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Managerial Implications

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cantele, S.; Cassia, F. Sustainability implementation in restaurants: A comprehensive model of drivers, barriers, and competitiveness-mediated effects on firm performance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 87, 102510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, R.J.; Rauter, R. Strategic perspectives of corporate sustainability management to develop a sustainable organization. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P.; Song, H.C. Similar but not the same: Differentiating corporate sustainability from corporate responsi-bility. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2017, 11, 105–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozioł-Nadolna, K. The Role of a Leader in Stimulating Innovation in an Organization. Adm. Sci. 2020, 10, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northouse, P.G. Leadership: Theory and Practice, 4th ed.; Sage Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, S.H.A.; Sultana, A.; Gul, A.; Sajjas, S.; Basit, A.; Qadir, A. Transformational Leadership Influence on Innovation Directly and Indirectly through Affective Commitment in Hotel Industry of Malaysia. Int. Rev. Manag. Mark. 2020, 10, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddleston, K.A.; Kellermanns, F.W.; Sarathy, R. Resource Configuration in Family Firms: Linking Resources, Strategic Planning and Technological Opportunities to Performance. J. Manag. Stud. 2007, 45, 26–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, G.; Iqbal, J.; Waheed, A.; Naveed Riaz, M. Relationship between Transformational Leadership Style and Innovative Work Behavior in Educational Institutions. J. Behav. Sci. 2012, 22, 18–32. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B.M.; Avolio, B.J.; Jung, D.I.; Berson, Y. Predicting unit performance by assessing transformational and transactional leadership. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Business Models, Business Strategy and Innovation. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 172–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrisman, J.J.; Chua, J.H.; De Massis, A.; Frattini, F.; Wright, M. The Ability and Willingness Paradox in Family Firm Innovation. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2015, 32, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formisano, V.; Quattrociocchi, B.; Fedele, M.; Calabrese, M. From Viability to Sustainability: The Contribution of the Viable Systems Approach (VSA). Sustainability 2018, 10, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, R.J. The Culinary Innovation Process—A Barrier to Imitation. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2004, 7, 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purvis, B.; Mao, Y.; Robinson, D. Three pillars of sustainability: In search of conceptual origins. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Hoogh, A.H.B.; Den Hartog, D.N. Ethical and despotic leadership, relationships with leader’s social responsibility, top management team effectiveness and subordinates’ optimism: A multi-method study. Leadersh. Q. 2008, 19, 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.K.; Busenitz, L.W.; Bird, B.; Gaglio, C.M.; McMullen, J.S.; Morse, E.A.; Smith, J.B. The Central Question in Entrepreneurial Cognition Research 2007. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2007, 31, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ángel, P.O.; Sánchez, L.S. R&D managers’ adaptation of firms’ HRM practices. R&D Manag. 2009, 39, 271–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaaffar, A.R.; Baharom, N.; Ali, J.; Zaini, A.F. Innovation practices among Malaysian University students toward business venture. Acad. Entrep. J. 2018, 24, 1528–2686. [Google Scholar]

- Stock, T.; Obenaus, M.; Slaymaker, A.; Seliger, G. A Model for the Development of Sustainable Innovations for the Early Phase of the Innovation Process. Procedia Manuf. 2017, 8, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surlemont, B.; Johnson, C. The role of guides in artistic industries—The Special Case of the ‘Star System’ in the Haute-Cuisine Sector. Manag. Serv. Qual. Int. J. 2005, 15, 577–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, C. The Michelin-Starred Restaurant Sector as a Cultural Industry: A cross-national comparison of restaurants in the UK and Germany. Food, Cult. Soc. 2010, 13, 493–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Restaurant Association. The State of Restaurant Sustainability. 2018. Available online: https://restaurant.org/downloads/pdfs/sustainability/restaurant_sustainability_research_report_2018 (accessed on 7 March 2021).

- Pérez, A.; Rodríguez-Del-Bosque, I. Sustainable development and stakeholder relations management: Exploring sustainability reporting in the hospitality industry from a SD-SRM approach. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 42, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holcomb, J.L.; Upchurch, R.S.; Okumus, F. Corporate social responsibility: What are top hotel companies reporting? Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2007, 19, 461–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyllick, T.; Hockerts, K. Beyond the business case for corporate sustainability. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2002, 11, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.J.; Kim, W.G.; Lee, H.Y. Coffee shop consumers’ emotional attachment and loyalty to green stores: The moderating role of green consciousness. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 44, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Kim, H.J. Environmental proactivity of hotel operations: Antecedents and the moderating effect of ownership type. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 37, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKerron, C.B.; Hoover, D. Waste and Opportunity 2015: Environmental Progress and Challenges in Food, Beverage, and Consumer Goods Packaging. 2015. Available online: https://www.nrdc.org/sites/default/files/consumer-goods-packaging-report.pdf (accessed on 7 March 2021).

- Sofuoglu, S.C.; Toprak, M.; Inal, F.; Cimrin, A.H. Indoor air quality in a restaurant kitchen using margarine for deep-frying. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 15703–15711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filimonau, V.; Lemmer, C.; Marshall, D.; Bejjani, G. ‘Nudging’ as an architect of more responsible consumer choice in food service provision: The role of restaurant menu design. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 144, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, C.; Wilberforce, N.; Kapur, A. Restaurant and food service life cycle assessment and development of a sustainability standard. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2011, 16, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perramon, J.; del Mar Alonso-Almeida, M.; Llach, J.; Bagur-Femenías, L. Green practices in restaurants: Impact on firm performance. Oper. Manag. Res. 2014, 7, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, C.-J.; Chen, K.-S.; Wang, Y.-Y. Green practices in the restaurant industry from an innovation adoption perspective: Evidence from Taiwan. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 31, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salzberg, A.C.; Gough, M.Z.; Suen, I.-S. Sustainable innovation behavior in restaurants. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2019, 22, 167–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavanagh, M.H.; Ashkanasy, N.M. The Impact of Leadership and Change Management Strategy on Organizational Culture and Individual Acceptance of Change during a Merger. Br. J. Manag. 2006, 17, S81–S103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, M.J.; Buhovac, A.J. Making Sustainability Work: Best Practices in Managing and Measuring Corporate Social, Environmental, and Economic Impacts, 2nd ed.; Berret-Koehler Publishers Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, Y.J.; Zheng, T.; Bosselman, R. Top managers’ environmental values, leadership, and stakeholder engagement in promoting environmental sustainability in the restaurant industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 63, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pless, N.M.; Maak, T.; Stahl, G.K. Developing Responsible Global Leaders Through International Service-Learning Programs: The Ulysses Experience. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2011, 10, 237–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantikei, B.; Usup, R.C.; Lelo, S.; Danes, J.N.; Meitiana. The Role of Responsible Leadership in Determining the Tri-ple-Bottom-Line Performance of the Indonesian Tourist Industry. Contemp. Econ. 2020, 4, 463–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdig, M.A. Sustainability Leadership: Co-creating a Sustainable Future. J. Chang. Manag. 2007, 7, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Mar Alonso-Almeida, M.; Bagur-Femenías, L.; Llach, J.; Perramon, J. Sustainability in small tourist businesses: The link between initiatives and performance. Curr. Issues Tour. 2015, 21, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.; Singh, S. How leaders impact employee creativity: A study of Indian R&D laboratories. Manag. Res. Rev. 2013, 36, 66–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuraik, A.; Kelly, L. The role of CEO transformational leadership and innovation climate in exploration and exploitation. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2019, 22, 84–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S.G.; Bruce, R.A. Determinants of innovative behavior: A path model of individual innovation in the workplace. Acad. Manag. J. 1994, 37, 580–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ailin, M.; Lindgren, P. Conceptualizing Strategic Innovation Leadership for Competitive Survival and Excellence. J. Knowl. Glob. 2008, 1, 87–107. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, J.J.P.; Vera, D.; Crossan, M. Strategic leadership for exploration and exploitation: The moderating role of environmental dynamism. Leadersh. Q. 2009, 20, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemanich, L.A.; Vera, D. Transformational leadership and ambidexterity in the context of an acquisition. Leadersh. Q. 2009, 20, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.A. Diversity as strategy. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2004, 82, 98. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Surie, G.; Hazy, J.K. Generative leadership: Nurturing innovation in complex systems. E:CO 2006, 4, 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Assink, M. Inhibitors of disruptive innovation capability: A conceptual model. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2006, 9, 215–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogabayev, T.; Maziliauskas, A. The definition and classification of innovation. Holistica 2017, 8, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiederig, T.; Tietze, F.; Herstatt, C. Green innovation in technology and innovation management—An exploratory literature review. R&D Manag. 2012, 42, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horbach, J. Indicator Systems for Sustainable Innovation; Physica-Verlag: Heidelberg, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rennings, K. Redefining innovation—Eco-innovation research and the contribution from ecological economics. Ecol. Econ. 2000, 32, 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Sustainable Manufacturing and Eco-Innovation: Framework, Practices and Measurement—Synthesis Report. 2009. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/innovation/inno/43423689.pdf (accessed on 16 March 2021).

- Johnson, C.; Surlemont, B.; Nicod, P.; Revaz, F. Behind the Stars—A Concise Typology of Michelin Restaurants in Europe. Cornell Hotel. Restaur. Adm. Q. 2005, 46, 170–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiatkawsin, K.; Sutherland, I. Examining Luxury Restaurant Dining Experience towards Sustainable Reputation of the Michelin Restaurant Guide. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H.; Spohrer, J. A research manifesto for services science. Commun. ACM 2006, 49, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottenbacher, M.; Gnoth, J. How to Develop Successful Hospitality Innovation. Cornell Hotel. Restaur. Adm. Q. 2005, 46, 205–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- den Hertog, P. Managing Service Innovation: Firm-Level Dynamic Capabilities and Policy Options. Ph.D. Thesis, Dialog Innovatie & Interactie, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ottenbacher, M.; Harrington, R.J. The innovation development process of Michelin-starred chefs. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2007, 19, 444–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilar Opazo, M. Discourse as driver of innovation in contemporary haute cuisine: The case of el Bulli restaurant. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2012, 1, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Baracskai, Z.; Dörfler, V.; Velencei, J. Business Creativity: An Evolutionary Approach. In Proceedings of the AoM 2007: The Sixty-Seventh Annual Meeting of the Academy of Management, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 3–8 August 2007. [Google Scholar]

- den Hertog, P.; Broersma, L.; Ark, B. On the Soft Side of Innovation: Services Innovation and its Policy Implications. Economist 2003, 151, 433–452. [Google Scholar]

- Ojasalo, K. Business and Design Competences in Service Innovation and Development. Bus. Rev. 2009, 13, 216–222. [Google Scholar]

- Verburg, R. Leadership, Innovation, and Sustainability. In Innovation for Sustainability—Business Transformations Towards a Better World, 1st ed.; Bocken, N., Ritala, P., Albareda, L., Verburg, R., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 117–133. [Google Scholar]

- Rickards, T.; Moger, S. Creative Leaders: A Decade of Contributions from Creativity and Innovation Management Journal. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2006, 15, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaudela-Baum, S.; Holzer, J.; Kocher, P.Y. Innovation Leadership—Führung Zwischen Freiheit und Norm; Springer Gabler: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nidumolu, R.; Prahalad, C.K.; Rangaswami, M.R. Why sustainability is now the key driver of innovation. IEEE Eng. Manag. Rev. 2013, 41, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarros, J.C.; Cooper, B.K.; Santora, J.C. Building a Climate for Innovation Through Transformational Leadership and Organizational Culture. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2008, 15, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosing, K.; Frese, M.; Bausch, A. Explaining the heterogeneity of the leadership-innovation relationship: Ambidextrous leadership. Leadersh. Q. 2011, 22, 956–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, D.I.; Chow, C.; Wu, A. The role of transformational leadership in enhancing organizational innovation: Hypotheses and some preliminary findings. Leadersh. Q. 2003, 14, 525–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalshoven, K.; Den Hartog, D.N.; De Hoogh, A.H. Ethical leadership at work questionnaire (ELW): Development and validation of a multidimensional measure. Leadersh. Q. 2011, 22, 51–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maak, T. Responsible Leadership, Stakeholder Engagement, and the Emergence of Social Capital. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 74, 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, Y.; Hollenhorst, S.; Harris, C.; Mclaughlin, W. Environmental management: A Study of Vietnamese Hotels. Ann. Tour. Res. 2006, 33, 545–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, F.; Chaudhry, M.N.; Batool, S.A. Assessment of key parameters in municipal solid waste management: A prerequisite for sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2014, 21, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, W.; Wang, J.; Hua, X.; Liu, Z. Entrepreneurship and high-quality economic development: Based on the triple bottom line of sustainable development. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2021, 17, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, L.W. Social Research Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches: International Edition, 7th ed.; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cassell, C. Creating the interviewer: Identity work in the management research process. Qual. Res. 2005, 5, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkmann, S.; Kvale, S. InterViews—Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Michelin Guide. Alle Sternerestaurants—Guide MICHELIN Deutschland 2021. 2021. Available online: https://guide.michelin.com/de/de/article/news-and-views/guide-michelin-2021-alle-sternerestaurants (accessed on 7 March 2021).

- Noble, H.; Smith, J. Issues of validity and reliability in qualitative research. Évid. Based Nurs. 2015, 18, 34–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, E.A. The Case for Inductive Theory Building. J. Manag. 2007, 33, 867–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidel, J.; Kelle, U. Different functions of coding in the analysis of textual data. In Computer-Aided Qualitative Data Analysis: Theory, Methods and Practice, 1st ed.; Kelle, U., Ed.; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 1995; pp. 52–61. [Google Scholar]

- Basit, T. Manual or electronic? The role of coding in qualitative data analysis. Educ. Res. 2003, 45, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitzko, S.; Spiller, A. Comparing “Leaf-to-Root”, “Nose-to-Tail” and Other Efficient Food Utilization Options from a Consumer Perspective. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stierand, M.; Dörfler, V.; Lynch, P. Haute Cuisine Innovations: The Role of the Master-Apprentice Relationship. In Proceedings of the BAM 2008, Harrogate, UK, 9–11 September 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, P.; Pérez, A.; Del Bosque, I.R. Measuring Corporate Social Responsibility in tourism: Development and validation of an efficient measurement scale in the hospitality industry. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 365–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Considerations | Design of this Research |

|---|---|

| Internal Validity | 1. Research questions and hypotheses derived fromunderlying literature and theoretical model 2. Results of the conducted study compared with existing literature |

| External Validity | 1. Structured interview questions 2. Eligibility criteria: expert sampling method |

| Reliability | 1. Development of a question catalog 2. Recordings of interviews and transcripts to assessconsistency with field notes of researcher |

| Framework Themes and Codes | Categories | Freq. |

|---|---|---|

| Sustainability in Michelin-Starred Restaurants | ||

| Environmental dimension | Product utilization Unit integration Product seasonality Food waste Packaging Use of renewable energies | 6/9 5/9 2/9 2/9 2/9 2/9 |

| Social dimension | Education of stakeholders Feedback from guest/employees Equitable pay and treatment | 4/9 2/9 2/9 |

| Economic dimension | Resource utilization planning Cross-department calculations Waste disposal costs | 3/9 1/9 2/9 |

| Cultural dimension | Cultural asset of cooking Quality culture impact Embedded in all dimensions | 1/9 2/9 1/9 |

| Sustainability motivations | Image Reputation Expectations of stakeholders Personal conviction Sustainable practices’ impact on product | 5/9 2/9 5/9 4/9 3/9 |

| Leadership in Michelin-Starred Restaurants | ||

| Leadership style | Cooperativity and amicable Appreciation Rigor Discipline Open-minded Honest communication | 5/9 4/9 4/9 3/9 2/9 2/9 |

| Modern leadership philosophy | Common vision/joint targets Employee objective flexibility Innovation “culture of errors” “Team spirit” creativity Scheduled “innovation days” Innovative culture/leadership = improved performance | 8/9 5/9 5/9 5/9 3/9 6/9 |

| Sustainable leadership | Role models in practice Facilitating ethical values Being authentic in sustainable actions | 7/9 5/9 4/9 |

| Innovation in Michelin-Starred Restaurants | ||

| Innovation definitions | New products New compositions on the guest’s plate New interpretation of classical dishes New cooking methods New techniques All areas of a restaurant Arouse positive emotions, a pleasant feeling, and an exciting dining experience | 3/9 4/9 3/9 3/9 2/9 3/9 3/9 |

| Sources of innovative ideas | Leader–employee collaboration Exchange with external colleagues or producers Traveling Dining out Social media Nature Experimentation and evolution of initial ideas | 3/9 5/9 5/9 4/9 5/9 2/9 3/9 |

| Linkage between Sustainability, Leadership and Innovation | ||

| Innovative leadership | Leadership style fosters innovative motivation Positive climate increased creativity Impacts employee satisfaction Improves employee–company identity | 9/9 6/9 5/9 2/9 |

| Sustainability and leadership | Ensures long-term employee loyalty Sustainable products drive innovation Innovative products/solutions impact protection of the environment | 4/9 2/9 2/9 |

| Sustainability and innovation | Conflicting interests between sustainability and innovation Financial profitability difficult in sustainable haute cuisine Difficult to assure quality of sustainable products Higher workload from sustainable practices/products | 5/9 4/9 4/9 2/9 |

| Sustainable innovation capability | ||

| Critical factors/practices | Meeting/exceeding expectations of stakeholders for successful innovation Long-term planning critical Cautious and intelligent gradual changes Continuous innovation progress | 5/9 4/9 4/9 3/9 |

| For competitive advantage | Brand loyalty and consistency of the restaurant’s concept Knowledge of the customer base/needs Sustainable practices High quality standards Classical cooking signature with focus on traditional ingredients/practices Combination of classical and innovative Cuisine | 9/9 8/9 4/9 4/9 4/9 2/9 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mrusek, N.; Ottenbacher, M.C.; Harrington, R.J. The Impact of Sustainability and Leadership on the Innovation Management of Michelin-Starred Chefs. Sustainability 2022, 14, 330. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010330

Mrusek N, Ottenbacher MC, Harrington RJ. The Impact of Sustainability and Leadership on the Innovation Management of Michelin-Starred Chefs. Sustainability. 2022; 14(1):330. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010330

Chicago/Turabian StyleMrusek, Natascha, Michael C. Ottenbacher, and Robert J. Harrington. 2022. "The Impact of Sustainability and Leadership on the Innovation Management of Michelin-Starred Chefs" Sustainability 14, no. 1: 330. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010330

APA StyleMrusek, N., Ottenbacher, M. C., & Harrington, R. J. (2022). The Impact of Sustainability and Leadership on the Innovation Management of Michelin-Starred Chefs. Sustainability, 14(1), 330. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010330