Abstract

Amongst the various factors that managers need to consider when designing a CRM campaign is the cause’s geographic scope, i.e., should the CRM campaign benefit local, national, or international communities? Although previous research has examined the importance of geographic scope in the effectiveness of the CRM campaigns, it has largely ignored consumer reactions to CRM campaigns from a local cultural identity perspective, such as ethnocentric identity. This study brings together these two important factors to examine (through the lens of Social Identity Theory) how consumer ethnocentrism affects CRM effectiveness in campaigns varying in geographic scope. We test our hypotheses through an experimental study of 322 British consumers and three different geographic scopes (UK, Greece, and Ethiopia). Our results show that ethnocentric consumers show a positive bias towards products advertised through national CRM campaigns; however, there is a diversity of reactions towards different international geographic scopes, based on the levels of ‘perceived economic threat’. Ethnocentric consumers prefer international CRM campaigns that benefit people located in a country posing a lower vs. a higher economic threat to the domestic economy and the self. Our study contributes to a broader understanding of factors affecting the effectiveness of CRM campaigns and help managers design better CRM campaigns by carefully selecting the geographic scope, after considering a rising consumer segment: the ethnocentric consumer.

1. Introduction

Cause-related marketing (CRM) is an increasingly popular corporate social responsibility initiative with firms today [1] driven by increasing consumer demand for brands that stand up for the social issues they care about [2,3]. CRM has now become the third largest sponsorship category worldwide, with funds reaching $62.7 billion in 2017, while it is projected to grow by 4.4% per year [4]. CRM refers to a company that offers to contribute a specified amount of revenues from sales of its products or services to a designated social cause [5]. For example, a popular CRM campaign has been Starbuck’s fight for AIDS, where, every time one purchases a particular red cup of Starbuck’s coffee, the company donates $0.15 to fight AIDS in Africa.

An effectively run CRM campaign allows a firm to satisfy both its social commitment to ‘do good’ as well as its financial imperative to ‘do well’ [6,7]. Effective CRM campaigns can bring benefits to firms, such as increased sales [8,9], stronger consumer-brand identification [10,11,12], or better corporate image [11,12]. However, not all CRM campaigns result in positive consumer responses [5,13]. CRM campaigns may cause negative consumer emotions such as skepticism [14], anger [15], or guilt [11,12] and have backfired, causing detrimental effects on the sponsoring brand [16]. Therefore, it is important for marketers to understand how to design effective CRM campaigns, eliciting positive consumer responses.

Extant research on CRM effectiveness has suggested various factors that can influence the success of such a campaign, ranging from the characteristics of the social cause to the characteristics of the firm and the fit between them as well as the characteristics of the consumer (for an overview, see [17,18]). In addition, within the research stream examining the characteristics of the social cause, many researchers have highlighted that the cause’s geographic scope (or cause proximity) is an important characteristic to be examined [5,19,20]. The geographic scope refers to the location of the social cause supported by a CRM campaign [21] and reflects its physical proximity to the consumer [22]. In other words, the geographic scope (or cause proximity) determines whether a cause deals with local/national issues and local/national beneficiaries or global issues and foreign beneficiaries [20]. For example, a CRM campaign with a national scope aims to support compatriots, while a CRM campaign with international scope aims to support foreigners.

However, little research has been produced so far examining the role of geographic scope in CRM effectiveness or any moderators in this context [20,23], while extant literature within this stream has been inconclusive [24], calling for additional research. In addition, within the CRM effectiveness literature, hardly any research exists on the role of consumer local cultural identities [24] such as ethnocentrism, which is currently on the rise globally [25] and one of the most important factors that have affected consumer preferences during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown period [26]. As initially noted by Rosenblatt [27], whenever countries consider themselves under attack or threatened by outsiders, ethnocentric feelings increase. Recent examples of increased ethnocentrism have been noted in the aftermath of the global financial crisis of 2008 [28] as well as during the coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak [26,29,30,31]. As these considered threats by outsiders increase (e.g., a financial crisis, a pandemic, climate change) so does consumer ethnocentrism. Consumer ethnocentrism (CET) refers to a subset of ethnocentrism applied into the marketing context [32] and reflects economic motives for one’s own group bias [33].

Despite the large body of literature examining CRM effectiveness, there has been minimal research dedicated to geographic scope [20,23] as well as on ethnocentric effects on the success of CRM campaigns [24]. In this study, we examine how consumer ethnocentrism affects consumer intentions towards buying products advertised through CRM campaigns varying in geographic scope. To the best of our knowledge, CET has not been examined as a determinant of CRM effectiveness yet. Moreover, past CRM studies examining the role of geographic scope in CRM effectiveness have only focused on comparisons between local, national, and international scopes without any comparisons between different international scopes. In this study, we focus on comparisons between one national scope and two different international scopes, varying in ‘perceived economic threat’ levels. The perceived economic threat concept has been defined by Sharma et al. [34] as the threat that foreign competitors pose to individual consumers or the domestic economy) and has previously been identified as an important factor moderating the effects of consumer ethnocentrism [34]. For example, it has been found that people who work in industries threatened by foreign competition (e.g., textiles and automobiles) show higher consumer ethnocentric tendencies [34]. This is because the fear of losing jobs (either one’s own or a related person’s) is stronger when involved in threatened industries. Similarly, the threat that foreign competitors pose to the individual or to the domestic economy varies between different competitors and may differently influence consumer reactions to imports from these competitors. In this study, the perceived economic threat of the foreign country is used to help us distinguish between different international geographic scopes and examine any consumer differences towards various international geographic scopes that differ in levels of perceived economic threat. This way, we fill an important gap in the literature on the determinants of CRM effectiveness.

In this study, we draw on the theoretical lens of Social Identity Theory [35,36] to argue that CET is an important consumer characteristic that affects CRM effectiveness, as measured by purchase intentions. In particular, we argue that its impact is positive for national CRM campaigns while its impact on international ones varies and depends on the ‘perceived economic threat’ of the international scope. The findings offer useful insights to managers who design CRM campaigns on how best to select the geographic scope of their campaigns by also considering the rising segment of ethnocentric consumers.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Determinants of CRM Effectiveness

Previous researchers have already identified a large number of factors that can make CRM effective, ranging from organizational characteristics, such as the company’s origin [37] or the fit between organizational characteristics and the social cause, i.e., the brand–cause fit [38,39,40,41] or consumer characteristics such as moral values and emotions [11,42,43,44], perceived motive of the brand [11], and trust in CRM campaigns [45], as well as the degree of overlap between consumer’s characteristics and the cause (i.e., consumer cause identification) [22]. Finally, many researchers have focused on examining various characteristics of the CRM campaign such as the product type involved in the campaign [46,47] or the donation size [48,49]. Finally, another large body of research has focused on the characteristics of the social cause. Such characteristics may include the type of the cause, i.e., whether the cause addresses primary needs (e.g., health and safety) or secondary needs (e.g., education) [22,50,51], its acuteness, i.e., whether the cause is associated with a sudden disaster or an on-going need [21,52], and its geographic scope (i.e., whether the cause addresses a local, national, or international need). A detailed overview of most of these factors is provided by Galan-Ladero et al. [17] or Fries [18]. However, amongst the most important factors determining CRM effectiveness has been its geographic scope [5,19]. Contrary to consumer characteristics or organizational characteristics, the geographic scope of a CRM campaign is an interesting campaign design element for managers since they can directly control it.

2.2. The Role of the Geographic Scope in CRM Effectiveness

The geographic scope of the CRM campaign refers to the location of the social cause supported by the campaign and reflects its physical proximity to the consumer [22]. Depending on what the geographic scope of the CRM campaign is, the beneficiary of the social cause can be a local, regional, national, or international population [21].

Previous studies, examining the role of geographic scope on affecting the success of the CRM campaign have been conflicting and equivocal [24]. Some studies have found a consumer preference for CRM campaigns linked to local scope compared to national or international ones, e.g., [53,54,55], other studies have found no significant difference on consumer preferences due to scope [21,37,56], while other studies point towards consumer preferences for an international rather than a national scope [57], while others report mixed results, suggesting that cause scope may be a ‘double-edged’ sword [22].

In addition to the mixed results discussed above, extant research in CRM effectiveness has focused on comparisons between local/national vs. international scopes while remaining agnostic to any differences between various international scopes. Previous scholars have pointed to the need for more research on the role of geographic scope in CRM effectiveness as well as any moderators in this context [20]. In this study, we fill a first gap in the literature by examining the role of geographic scope in the effectiveness of CRM campaigns by comparing not only national and international scopes but also different international scopes. To the best of our knowledge, extant literature on CRM effectiveness has not yet examined any differences between various international geographic scopes.

2.3. The Effects of CET and Perceived Economic Threat on Purchase Intentions

Shimp and Sharma [32] initially defined consumer ethnocentrism as the “appropriateness, indeed morality, of purchasing foreign-made products”. The concept has been used by marketing researchers to explain why consumers prefer products from their home country to foreign alternatives [32,58,59,60].

CET can be a major setback for brands trying to expand abroad [61]. As such, it has attracted attention from international marketing scholars who have examined it as a predictor of purchase intentions (PI), suggesting a negative bias of ethnocentric consumers towards international products [62] as well as a positive bias for domestic products [61]. However, CE is a more consistent predictor of domestic rather than foreign products [59].

In addition, the effects of consumer ethnocentrism may not be universal across all products and countries [59]. For example, previous studies have found that the effect is not significant in low cost/convenience products [63]. Additionally, CET’s positive bias for local vs. global product purchases is stronger in low symbolic products and in countries at a lower economic development stage [64]. Therefore, CET effects are considered product- and country-specific [59,63,65]. This conclusion points to the need to examine CET effects in various countries and products.

To date, there has been hardly any research examining how CET affects CRM products, i.e., products linked with a CRM campaign supporting a social cause. One notable exception in the CRM research stream is the study by Strizhakova and Coulter [24], who have examined CET as a moderator in the link between the geographic scope of the campaign and consumer attitudes toward the firm. Their results could not confirm CET as a significant moderator. However, they did not examine CET as a determinant of CRM effectiveness (measured by Purchase Intentions). Therefore, in this study, we fill a second gap in the literature, by examining CET as a determinant of consumers’ purchase intentions towards CRM products.

In addition, extant literature has suggested various moderators affecting the impacts of CET on purchase intentions such as ‘perceived economic threat’ and ‘product necessity’ [34], ‘cultural similarity’ and ‘product categories’ [63], as well as ‘economic competitiveness’ [59]. In this study, we focus on ‘perceived economic threat’ (i.e., the threat that foreign competitors pose to individual consumers or the domestic economy; [34]) not only because it has been under-researched but also because it seems relevant to the context of this study. In particular, it can help us distinguish between different international locations and examine any consumer differences towards various international geographic scopes.

To conclude, based on an overview of prior CRM and CET literatures, this study contributes to extant CRM effectiveness literature by examining how CET affects consumer intentions towards buying products advertised through CRM campaigns, varying in geographic scope and whether this impact is universal across different international geographic scopes.

3. Conceptual Framework

3.1. Social Identity Theory and Consumer Ethnocentrism Theoretical Background

Social Identity Theory (SIT) [35,36] attempts to explain when and why people identify with and behave as part of a group [33,36]. Social identity is defined as “that part of an individual’s self-concept which derives from his knowledge of his membership of a social group (or groups) together with the emotional significance attached to that membership” ([35] p. 69). According to Social Identity Theory, people strive to achieve or maintain a positive social identity to boost their self-esteem [36]. This positive identity derives largely from favorable comparisons made between one’s own group (in-group) and other groups (out-groups) [36,66]. In a country context, the home country is typically considered the in-group, whereas foreign countries represent the out-groups [33,58]. Social Identity Theory makes a clear distinction between a person’s behavior toward the in-group (e.g., domestic country) and the out-group (e.g., foreign countries).

Consumer ethnocentrism is conceptually anchored in Social Identity Theory [60,67]. It indicates consumers’ tendencies to “distinguish between products of the in-group (home country) and out-groups (foreign countries) and to avoid buying foreign products due to nationalistic reasons” ([58] p. 148). To an ethnocentric consumer, purchasing imported products is immoral and unpatriotic since it hurts the domestic economy and leads to a loss of domestic jobs [32].

Sumner ([68] p. 13) originally defined the concept of ethnocentrism as “the technical name for this view of things in which one’s own group is the center of everything, and all others are scaled and rated with reference to it”. The main characteristics of ethnocentrism are feelings of pride in one’s own group and a perception of other groups’ inferiority [68]. Consumer ethnocentrism is a subset of ethnocentrism that applies to marketing context [32] and captures only economic motives for one’s own group bias [33].

Extant literature suggests that the domestic country bias in the concept of consumer ethnocentrism occurs because of anti-out-group motives (i.e., the rejection of foreign products) but also because of pro-in-group motives (i.e., the desire to support the domestic economy by purchasing domestic products) [59,60]. As such, CET is different from the concept of nationalism/national identity, which is primarily a pro-in-group concept [60] because in-group bias due to national identity results solely from a person’s feeling of attachment to the in-group without any explicit reference to out-groups [60].

Finally, according to SIT, people belong to a variety of groups that may identify with, according to their gender, religion, political orientation, nationality, etc., thus having multiple social identities [69]. Moreover, even though an individuals’ identification with a social group leads to a tendency to subscribe to the group norms and act on behalf of group goals, e.g., [70,71], this does not mean that identification with that particular social group is influential in all situations. Thus, which identity is influential in a situation is dependent largely on the context and reflects the identity’s salience in that context [69]. In other words, although people are motivated to preserve consistency in identity through their behavior [72], the strength of identity-consistent behavior depends on external and situational factors [73,74]. Situational stimuli may activate the accessibility of a certain social identity to exert a strong effect on behavior [75]. One such situational stimuli is the geographic scope of a CRM campaign.

3.2. Social Identity Theory and Consumer Ethnocentrism in the CRM Context

The geographic scope in a CRM campaign is a situational factor that may activate the accessibility of the ethnocentric identity. When consumers are exposed to a CRM ad that the beneficiary is shown (compatriot vs. foreigner), those with an ethnocentric identity salience are more likely to perceive a higher level of identity congruence between the CRM ad and consumers’ own identities and behave in an identity compatible way, i.e., show a preference for this product. More importantly, as the geographic scope of the campaign is quite visible and no other (relevant for ethnocentric consumers) situational factors dominate the campaign such as a brand’s place of origin, the geographic scope of the campaign (national vs. international) may become the dominant cue to activate the relevant social identity, i.e., the ethnocentric identity.

CRM scholars have found that CRM products prompt consumers to express their social identity [69] and by purchasing a CRM product they can subsequently and positively influence their particular social identity [73]. Therefore, consumers’ social identity plays a significant role in their CRM product purchases.

Since people strive to maintain identity congruence [72], we can argue that the purchasing of CRM products that benefit compatriots is a behavior compatible with consumers’ ethnocentric identity. Therefore, we expect to see a positive bias towards national CRM products. In addition, since ethnocentric identity is both a pro-in-group as well as an anti-out-group concept, it can also be argued that the avoidance of purchasing CRM products that benefit foreigners is also compatible with consumers’ ethnocentric identity. Therefore, consumers are expected to show a negative bias towards international CRM products. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Consumers’ ethnocentrism positively affects their intentions towards purchasing products advertised through national CRM campaigns.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Consumers’ ethnocentrism negatively affects their intentions towards purchasing products advertised through international CRM campaigns.

3.3. Are All International Scopes Equally Penalised by Ethnocentric Consumers? The Role of Perceived Economic Threat

According to Shimp and Sharma [32], to an ethnocentric consumer, it is inappropriate, immoral and unpatriotic to purchase foreign products since it hurts the domestic economy and leads to a loss of domestic jobs. Sharma et al. [34] suggested that the fear of losing jobs (either one’s own or a related person’s) or the fear of hurting the domestic economy influences consumers’ reactions to foreign products. Moreover, people who are involved in threatened industries due to foreign competition show higher consumer ethnocentric tendencies [32]. Therefore, Sharma et al. [34] suggested a moderating factor between CET and consumer attitudes towards foreign products, which they called ‘perceived economic threat’ and defined as “consumers’ concerns about the threat that foreign competitors pose to them personally and/or to the domestic economy” (p. 29). For example, in the UK context, British people who work (or are related to someone who works) in construction or manufacturing industries, which face increased competition from foreign immigrants, may fear for their jobs (or the jobs of people they are related to) and display stronger ethnocentric tendencies compared to those citizens working in industries with less competition from foreigners.

Indeed, Sharma et al. [34] have found strong empirical support for the moderating role of perceived economic threat in the relationship between CET and attitudes towards foreign products. Along these lines, we argue that the relationship between CET and purchasing international CRM products may be moderated by the perceived economic threat that international scopes pose to the domestic economy. Consistent with Social Identity Theory, an international scope that is perceived as posing a high economic threat will offer a strong situational cue to ethnocentric consumers, will activate their ethnocentric identity, and would likely avoid purchases. Similarly, an international scope that is perceived as a low economic threat will offer a weak situational cue to ethnocentric consumers and may not activate their ethnocentric identity. Therefore, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Consumers’ ethnocentrism impact on purchasing products advertised through international CRM campaigns is stronger (weaker) for countries perceived as posing a higher (lower) economic threat.

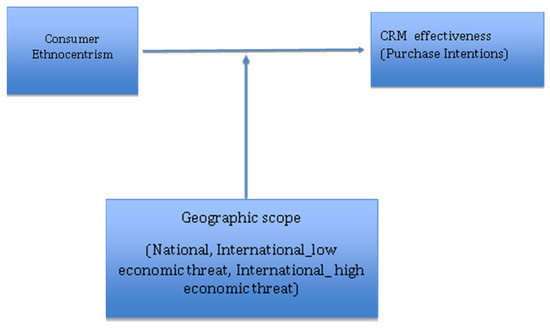

The conceptual model of our study is shown on Figure 1 below.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model.

4. Methodology

4.1. Experimental Design and Data Collection

In order to test our hypotheses, an advertisement-based survey experiment 1 × 3 (geographic scope: national vs. International_high threat vs. International_low threat) between subjects’ design was set up and conducted on-line using the Qualtrics platform, utilizing their own on-line consumer panels (Qualtrics panels). An online panel is an electronic database of registrants who have indicated a willingness to participate in future web-based studies and is a common method of data collection in the management/marketing fields [76]. We partnered with Qualtrics Panels for a more targeted empirical analysis to recruit participants that were British citizens only and we asked for a demographically diverse sample of participants, representative to UK population. To obtain a representative sample, Qualtrics applied a non-probability sampling technique by imposing quotas on gender, age, education, and ethnicity to match the demographic characteristics of UK population, according to the latest UK census data (UK census 2011). This way, we ensured a more representative sample of the UK population compared to common alternative methods of data collection, such as student samples or field studies. However, despite the numerous advantages, this sampling method is not free from disadvantages, as can be seen in the limitations section of this paper.

4.2. Sample and Procedure

Participants were recruited during December 2017. In the recruiting process, we limited participants to British citizens only. We focused on British consumer data since ethnocentric feelings had been on the rise in the country at that period, as manifested by the results of the Brexit referendum in June 2016 and the Brexit negotiations with the European Union that followed. Additionally, much CRM empirical research has previously focused on US consumers with hardly any studies performed on UK consumers (for a review of CRM studies, see [23]).

We collected 402 responses, via Qualtrics panels as discussed in the previous section. We deleted responses that failed the quality checks of the survey (e.g., the attention check questions) resulting in 322 valid and complete responses. The complete demographic characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1, below.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the sample, n = 322.

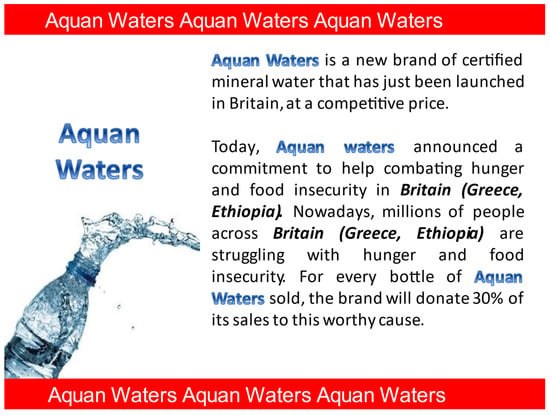

Three versions of a fictitious CRM advertisement (representing the three experimental conditions) were designed and shown to British consumers (see Figure 2 below). Participants were assigned randomly to each of the three conditions. After answering questions measuring their ethnocentric levels, they were shown a CRM campaign. After viewing the campaign, they were asked to fill in a short survey that measured their understanding of the campaign and its geographic scope (manipulation checks), their level of identification with the social cause (or cause importance), their purchase intentions, and some demographic variables in the end (age, gender, income, ethnicity, and education). Lastly, participants were debriefed using an information page that briefly explained the purpose of the study before the study was completed.

Figure 2.

The CRM campaign used in the study.

4.3. Stimuli and Manipulation of Independent Variables

The information was consistent across all three conditions, except for the geographic scope of the campaign. The adverts were showing a bottle of mineral water linked to the social cause of hunger and food insecurity (see Figure 2). In order to test how realistic the fictitious CRM campaign was (i.e., its ability to engage consumers), a pre-test was conducted by showing one campaign, with no CRM information and another one with the CRM information added. The campaign with the additional CRM information managed to elicit more favorable responses as measured by purchase intentions. Therefore, we continued the experiment, varying the geographic scope of the CRM campaign.

Additionally, the social cause of hunger and food insecurity was selected because it has been an important social issue in the minds of UK citizens [77]. Especially between 2006–2018, at the aftermath of the global financial crisis, the subsequent austerity, and the growing use of food banks, consumers’ perceptions in UK around growing poverty had increased from 52% in 2006 to 65% in 2018 [78], making ‘hunger and food insecurity’ an important social cause in UK. The importance of the cause increases consumer participation and leads to more positive attitudes towards the campaign [54,79]. Nevertheless, the importance of the cause was also measured at the consumer level through the concept of consumer–cause identification (cause importance), as suggested in previous studies [22], and was also added as a covariate in our analysis.

The campaigns were identical in all aspects apart from the variation in the geographic scope of the social cause (i.e., UK (national scope), Ethiopia (international_lower threat), and Greece (international_higher threat)). The particular international locations were chosen for the following reasons. First, we wanted to make the campaign as realistic as possible. Hence, we included two countries that were covered extensively in the media during the Christmas period of 2017 (data collection period) making consumers aware of the issue of hunger and food insecurity in both countries. In Ethiopia, the issue of hunger and food insecurity has been a well-recognized and ongoing issue while this issue in Greece had been a recent issue, manifesting itself during the global financial crisis of 2008 and the eurozone debt crisis that followed, forcing Greece into unprecedented austerity and welfare cuts and rising poverty. Hunger and food insecurity are strongly linked to poverty caused by austerity and welfare cuts [77]. Secondly, we wanted to include two countries that represented different levels of economic threat (high vs. low). Ethiopia, as a developing country, would most likely be considered a relatively low economic threat while Greece as a developed country (within the European Union) would most likely be considered a higher economic threat to the minds of ethnocentric British consumers. In addition, due to free mobility within the EU, many Greek people had been employed in UK in that period [80], trying to escape the recent economic crisis in Greece. An ethnocentric consumer would perceive immigration for employment an economic threat to particular domestic industries and/or to the self, if working in affected industries.

The campaign was intentionally missing information regarding the origin of the brand because we wanted to avoid any other cues relevant to the ethnocentric consumer that could affect the in-group vs. out-group bias. This approach has often been employed in previous CRM studies; see, for example, [21,22,53,54]. The campaigns were carefully designed by considering and controlling for all other major factors that have previously been identified in the literature as affecting consumer responses to CRM campaigns. For example, the campaigns were designed to address a primary need (i.e., hunger/food insecurity) since it has been found that consumers engage more with causes addressing primary rather than secondary needs [22,50,51]. Additionally, the campaigns had been designed with a high fit between the brand and the cause, (i.e., a healthy product brand such as a mineral water brand has a high fit with a health related cause, i.e., hunger/food insecurity). A high fit between the brand and the cause is also important in engaging consumers in a CRM campaign, e.g., [39,40,41]. Moreover, previous studies have shown that the higher the donation amount, the better [48,81,82]; hence, we chose a 30% donation size in order to fall within the high donation range (25–50%) used in previous studies, e.g., [46,81].

4.4. Measures

Established multi-item scales were adapted to measure all our constructs. For consumer ethnocentrism (CET), we used the CET scale, as suggested by Siamagka and Balabanis [28] with items shown in Appendix A. For purchase intentions (PI), we used the three item scale as suggested by Lii and Lee [7] or Putrevu and Lord [83] and shown in Appendix A. For consumer–cause identification (CCI), we used the 10-item semantic differential scale as suggested by Vanhamme et al. [22] and shown in Appendix A.

All multi-item constructs had loadings above 0.60. All indicators yield composite reliability (CR) above 0.92 and average variance extracted (AVE) above 0.57, thus indicating good construct reliability and validity [84] (see details in Appendix A). The Fornell–Larcker criterion [85] was also respected, thus confirming discriminant validity. Results of a Harman’s single factor test assessed through principal component analysis with no rotation [86] showed that one factor explains 19.95% of the variance in the study. This compares to five factors explaining 66.85% of the variance in the study. Results suggest that common method bias is not an issue in our study. All variables were tested for normality conditions before hypotheses testing and we used z-transformations before running the regressions. Lastly, all the final regression models were tested for multicollinearity (variance inflation factor), heteroskedasticity (Breusch–Pagan/Cook–Weiseberg test) and omitted variable bias (Ramsey Reset Test), and no problems were present.

4.5. Results

4.5.1. Manipulation Checks

A first manipulation check was used for the different geographic scopes. Participants were asked one question on whether the campaign featured a product supporting a national or an international cause, with all participants correctly identifying the scope of the campaign they were exposed to.

A second manipulation check was used for consumers exposed to the international campaigns, asking them about the perceived level of economic threat the particular country posed to the domestic economy and/or the self. Participants were asked to indicate on a 5-point Likert scale the extent they agreed to the following statement ‘Greece (Ethiopia) poses an economic threat to my job and to the UK economy in general’. Consumers shown the Greek campaign had a mean value of (M = 3.09), while consumers showing the Ethiopian campaign had a mean value of (M = 1.62). A t-test of significance indicated that the difference between these two groups was significant (p < 0.001). Hence, our second manipulation was successful, since most participants in the higher threat condition (Greece) perceived this scope as a higher threat compared to the lower threat condition (Ethiopia).

4.5.2. Regression Results

We used the STATA 13 software package for our analysis. The sample’s summary statistics and correlations are shown in Table 2 below. To test our hypotheses, we used a conditional OLS multiple regression analysis. For H1, we limited our sample to national CRM campaigns only (scope: UK), resulting in 106 observations (n = 106) (see Regression Model 1, Table 3), while for H2 and H3, we limited our sample to international campaigns only (scopes: Ethiopia and Greece), resulting in 216 observations (n = 216) (see Regression Model 2, Table 3). We run all the regression models with purchase intentions (PI) as the dependent variable and consumer ethnocentrism (CET) as the independent variable. We also added several covariates, such as age, gender, income, education level, ethnicity, and consumer–cause identification since previous research has suggested they these variables may affect consumer reactions to CRM campaigns or purchase intentions; see, for example, [22,60,63,87,88]. To test the third hypotheses (H3), we included an interaction term to the initial regression model (CET x scope) in order to compare the two international geographic scopes, where Scope 1 = Ethiopia and Scope 2 = Greece.

Table 2.

Means, standard deviations, correlations, and square root of average variance extracted ab.

Table 3.

OLS regression results ab.

We tested our first hypothesis (H1) through multiple regression analysis within national CRM campaigns only, with purchase intention (PI) as the dependent variable and CET as the independent variable and covariates (see Regression Model 1, Table 3). The coefficient of CET is positive and significant (b = 0.180, p = 0.063), indicating that CET has a positive and significant impact on consumer’s purchasing intentions for national CRM products. Hence, our first hypothesis (H1), suggesting that CET positively affects consumer purchasing intentions towards products advertised through national CRM campaigns, was confirmed. To test our second hypothesis (H2), we run a multiple regression analysis with the same regression model as previously, but this time, we limited our sample to international CRM campaigns only (see Regression Model 2, Table 3). The results of this model show that the coefficient of CET is insignificant (b = 0.102, p = 0.185), indicating that CET does not have a significant impact on international CRM products. Hence, our results cannot confirm the second hypothesis (H2), which was suggesting that CET negatively affects the purchase intention towards products advertised through international CRM campaigns.

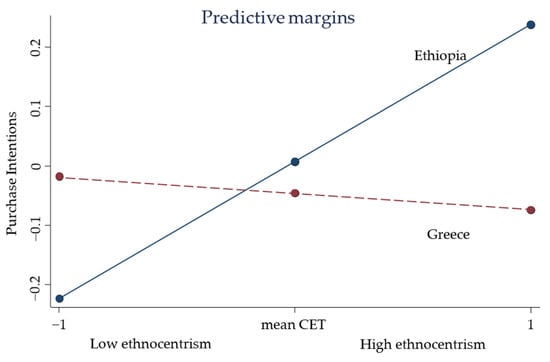

To test our third hypothesis (H3), we used multiple regression analysis within the international CRM campaigns, similarly to the model used in Hypothesis 2 (H2), but this time, we added an interaction term in the regression model (i.e., scope) to distinguish between international scopes (Ethiopia (lower threat) vs. Greece (higher threat)). The inclusion of the interaction term is a standard method of testing moderation effects in multiple regression analysis. As can be seen in Model 3 (Table 3), the interaction term between CET × Greece is negative and significant (b = −0.259, p = 0.064). This means that Greece reduces the impact that CET has on purchase intentions. In other words, this scope (Greece) negatively moderates the impact of CET on purchase intentions. Since Ethiopia is the reference category in this model, the results indicate that the impact of CET on PI when the scope is Greece is used is significantly different from the impact of CET on PI when the scope used is Ethiopia. In particular, the impact of CET on PI when the scope used is Greece is more negative compared to Ethiopia (which is the reference category in the regression model). As expected, between high_threat (Greece) and low threat (Ethiopia) scopes, our results confirm that there is a significant difference in purchasing intentions of ethnocentric consumers between the two international scopes. Hence, our third hypothesis (H3) suggests that, in international CRM campaigns, the impact of CET is stronger (i.e., more negative) for countries perceived as posing a higher economic threat, is confirmed. To better interpret these interaction effects, a graph of predictive margins was plotted (see Figure 3 below).

Figure 3.

Interaction effect between CET and international scopes on purchase intentions.

The graph shows the relationship between purchase intentions and CET across two different international CRM campaigns (Greece vs. Ethiopia). The dotted line indicates the effect for the Greek campaign (higher economic threat) and shows that the more ethnocentric a consumer is, the more severe the penalty will be for the Greek CRM product. In this condition, consumers’ purchasing intentions are significantly reduced as CET increases and are considerably lower compared to the campaign for Ethiopia (solid line). In addition, the graph shows that highly ethnocentric consumers do not seem to penalize Ethiopian campaign; quite the opposite, as they show a positive bias towards this campaign. The graph shows that there is a significant difference in consumers’ purchasing intentions for the international campaign for Ethiopia perceived as posing a low economic threat compared to Greece.

To conclude, the graph shows that non-ethnocentric consumers (or those below the mean level in the CET scale) show a preference for campaigns supporting Greece compared to Ethiopia, while highly ethnocentric consumers (or those above the mean CET level) show a clear preference towards campaigns supporting Ethiopia, hence penalizing Greece.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Discussion

The aim of this study was to examine how consumer ethnocentrism affects consumer intentions towards buying products advertised through CRM campaigns varying in geographic scope. We selected one national geographic scope and two international ones, varying in ‘perceived economic threat’ in order to examine any differences between the international scopes.

The interpretation of results is quite interesting since it offers new insights into the role of consumer ethnocentrism and geographic scope on the effectiveness of CRM campaigns. Our results confirmed that CET has a positive impact on consumers’ purchasing intentions for national CRM products (hence confirming our first hypothesis). These results are in line with the positive bias of ethnocentric consumers towards national products, as suggested in previous CET studies, e.g., [59,61].

We also found that CET effect in international CRM products was not significant (hence, the second hypothesis could not be confirmed). Nevertheless, our results in international scopes (without differentiating between high and low threat) confirm previous studies on the role of CET on consumer purchasing intentions for international low cost/convenience products that suggest that CET is a non-significant predictor of purchase intentions for these products; see, for example, [63]. Similarly, in our study (focusing on a low cost/convenience product), we found no significant effect of CET on international CRM campaign, confirming previous studies suggesting that CET may not be as a consistent predictor for international products as it is for national products [59].

However, the results of the third regression offer another insight on the impacts of CET. Since the interaction term between CET and Greece was negative and significant, CET’s impact on purchasing intentions was significantly lower for the Greek campaign compared to CET’s impact for the Ethiopian campaign (the reference category). Therefore, CET’s impact on purchasing intentions is moderated by the perceived economic threat the international scope poses to the domestic economy or to the self. More specifically, highly ethnocentric consumers show a stronger negative bias towards locations perceived as posing a higher economic threat to the domestic economy or the self. This result confirms the role of ‘perceived economic threat’ as a significant CET moderator, as has been suggested in the extant literature, e.g., [34].

In addition, the results of this study suggest that in a CRM campaign, with a visible geographic scope (and in the absence of any other location-relevant cues in the campaign), ethnocentric consumers show a positive bias towards national CRM campaigns, while they may penalize international CRM campaigns, depending on the perceived economic threat the international scope poses to the domestic economy/self. Therefore, this study offers new insights into how CET operates in a new context, that of CRM campaigns.

Our results could also be compared with previous studies in the CRM effectiveness literature, e.g., [20,24] suggesting that the geographic scope of the campaign is an important factor to be considered. In addition, the role of geographic scope (or cause proximity) has often been examined in CRM literature through a spatial lens (i.e., physical distance framework), suggesting the shorter the physical distance, the better for positive consumer reactions, e.g., [54]. As illustrated in Figure 3, our results suggest that, although this is true for non-ethnocentric or lower ethnocentric consumers (showing a preference for Greece (shorter physical distance) vs. Ethiopia (longer physical distance), this is not true for highly ethnocentric consumers. This consumer segment, driven by economic motives, is more likely to penalize products linked with international locations that pose a high economic threat to the domestic economy/self. Hence, contrary to the spatial lens predictions, we found that highly ethnocentric consumers show a stronger negative bias towards Greece (shorter physical distance) than Ethiopia (longer physical distance).

In addition, our results also reveal that highly ethnocentric consumers may not penalize (or may even reward) international CRM campaigns when the international scope represents a very low/no threat to the domestic economy/self. Previous studies have suggested that ethnocentric consumers act with empathy towards their compatriots and are driven by economic motives [33,63]. Our study shows that they may also act with empathy towards economically disadvantaged foreign populations (that are not perceived as posing an economic threat to the country/self) and consider them as part of their in-group, hence supporting them through their purchases. Social identity literature suggests that boundaries between in-group and out-groups are not fixed and who is considered part of the in-group typically depends on how the individual identifies or at least affiliates with it [89]. Although, typically, foreign countries are considered part of the out-groups [33,58], this is not always the case.

Finally, it is worth noting that although our study was conducted in December 2017 (soon after the Brexit referendum in UK), our results are even more relevant today since ethnocentric feelings are on the rise across the world because of more recent threats such as the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic has increased fear and uncertainty across the world and has changed perceptions regarding foreign countries, resulting in increased ethnocentric feelings [25,30,31]. In addition, it has recently been found that ethnocentrism has been one of the most important factors affecting consumer preferences during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown period [26]. Hence, our findings are particularly important and relevant nowadays.

5.2. Theoretical Contributions

This study offers new insights on how CET operates within a new context, that of CRM campaigns with varying geographic scopes. In fact, our study has shown that in the context of CRM campaigns, the geographic scope acts as a situational cue for ethnocentric consumers for domestic country bias. In addition, our study extends current literature on CRM effectiveness, e.g., [20,21,22,23,24,43], by suggesting a new significant factor that can affect the success of CRM campaigns, consumers’ ethnocentric identity. This identity should be considered in future studies examining the role of geographic scope on CRM effectiveness.

In addition, our study extends current CRM literature examining the role of geographic scope [20,22,24,53] by comparing various international scopes. Previous researchers in that stream have focused on national vs. international comparisons while ignoring any comparisons between various international scopes. In this study, we confirm there is a diversity of consumer responses towards international locations that vary in economic threat levels.

Finally, many previous studies examining the role of geographic scope have used a spatial lens, e.g., [20,24,54]. Our study reveals new boundaries for using a spatial lens when examining the geographic scope of the campaign. In line with previous scholars, e.g., [20], who have suggested that, in CRM campaigns, the shorter the cause proximity is not always better (due to important factors that interact with cause proximity), we also confirm this proposition. As shown in this study, highly ethnocentric consumers are an important consumer segment that may affect the success of CRM campaign but do not always prefer the shorter physical location. Their purchasing intentions depend on the perceived economic threat [34] of the physical location. This is an important finding revealing new boundaries of how a spatial lens operates when other factors such as an ethnocentric identity and cause proximity are considered together.

5.3. Managerial Implications

Managers should consider the geographic scope of their campaign especially when operating in highly ethnocentric environments. In this context, managers should design either national CRM campaigns or international CRM campaigns with scopes perceived as low/no economic threat to the domestic economy. Managers who wish to support an international cause should remember that not all international scopes are equally penalized by ethnocentric consumers. International locations that pose a lower economic threat to the domestic economy will be a better choice compared to scopes posing a higher economic threat. In addition, international scopes that pose a very low or no economic threat may be as good as national scopes since in this case consumers may show a positive bias towards this campaign. This result is important not only for designing effective CRM campaigns but also for encouraging managers to support more international causes through their campaigns. Extant donations literature suggest that most corporate donations go to national causes [90] leaving a big shortage of money for international causes [91]. Thus, the results of this study may help managers reverse this trend in corporate donations.

Finally, our results indicate that managers of international brands may be able to overcome the negative bias of ethnocentric consumers for their products by carefully selecting the scope of their CRM campaigns. For example, in the absence of any cue to the brand’s place of origin, MNCs involved in CRM campaigns with national scope or a scope that poses no economic threat to the domestic economy may be able to overcome the negative bias of ethnocentric consumers for their foreign products.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Several limitations in the present study should be acknowledged. First, other factors that could influence the in-group vs. out-group bias, such as the place of origin [59], consumer animosity [92], consumer affinity [93], or cultural similarity [65], were not considered in this study. To comprehensively explain the ethnocentric effects towards campaigns with varying geographic scopes, future studies could try also addressing these factors.

Second, there are certain limitations around our sample. In particular, our study involved a small sample of British consumers with cross-sectional data. These results may not be free from endogeneity bias. As suggested by previous scholars [43], to address this limitation, future researchers should collect data at multiple points in time. Additionally, despite our efforts to collect a representative sample of UK population using Qualtrics panels, this type of non-probability sampling technique introduces a source of bias to the results (as it is not truly random); hence, our findings may not be generalizable to the UK population. Qualtrics panels have often been embraced by many management and marketing scholars, e.g., [94,95,96], owing to the numerous benefits they provide over traditional ‘convenience’ samples. For example, they provide researchers a convenient way to reach a potentially unlimited number of participants while keeping costs (financial and time) to a minimum [76]. In addition, online panels give researchers access to a more diverse pool of participants, resulting in more representative samples of the population and more generalizable results [97]. Moreover, participation in the research is truly voluntary, as participants can freely decide whether to volunteer to participate in the survey, hence increasing attention and effort while completing the survey [97]. However, on the flip side, participants in the online panel may pose as participants from the population of interest while they may not be. In addition, online panels utilize consumers who have internet connectivity and actively participate in consumer research studies, thus making them potentially more engaged in global consumer culture compared to the rest of the population [94], hence introducing another source of bias in the results. Therefore, our findings may not be generalizable to the UK population.

Third, in this study, we have chosen one national country (UK) and two international countries (Greece and Ethiopia) to test any consumer differences towards different international geographic scopes. Since CET effects are considered country-specific [59], we do not know if our results would change when using different international or national countries; hence, our results cannot be generalized beyond the scope of this study. In addition, in this study, we used a low cost/convenience product, but since CET effects are also considered product-specific [59], it would be good for future scholars to replicate this study across different countries and products. Finally, our study used the social cause of hunger and food insecurity. Although this cause has been reported in the literature as important for British consumers in the UK [77], other causes may function differently [98] and future studies should examine different causes or even allow participants to select a cause that is important to them; see, for example, [99].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.B.; methodology, I.B.; formal analysis, I.B. and D.M.; writing—original draft preparation, I.B.; writing—review and editing, I.B. and D.M.; funding acquisition, I.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was funded by the Business Economic and Informatics School Research Grant (SRG), Department of Management, Birkbeck, University of London, UK.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the department of Management, Birkbeck College, University of London, UK on 30 November 2016.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data used in this study can be found at Figshare: doi:10.6084/m9.figshare.17099825.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A. Constructs and Measures

Appendix A.1. Consumer Ethnocentrism (CET)

Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree).

Cronbach’s a: 0.933, CR: 0.928, AVE: 0.570.

- Buying British goods helps me to maintain my British identity.

- I believe that purchasing British goods should be a moral duty of every British citizen.

- It always makes me feel good to support British products.

- A real Briton should always back British products.

- British people should always consider British workers when making their purchase decisions.

- I would be convinced to buy domestic goods if a campaign was launched in the mass media promoting British goods.

- If British people are made aware of the impact on the economy of foreign product consumption, they will be more willing to purchase domestic goods.

- I would stop buying foreign products if the British government launched a campaign to make people aware of the positive impact of domestic goods consumption on the British economy.

- I prefer buying British products because I am more familiar with them

- I prefer buying British products because I am following the consumption patterns of those passed on to me by my older family members.

Appendix A.2. Purchase Intentions (PI)

Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree).

Cronbach’s a: 0.920, CR: 0.920, AVE: 0.793.

- 11.

- It is very likely that I will buy this brand in the future.

- 12.

- I will consider purchasing this brand the next time I need this product.

- 13.

- I will try this brand in the future.

Appendix A.3. Consumer Cause Identification (CCI)

10 item Semantic differential scale (5-point items).

Cronbach’s a: 0.960, CR: 0.960, AVE: 0.710.

I feel that the social cause of combating hunger and food insecurity (is):

- 14.

- important/unimportant

- 15.

- of concern/of no concern

- 16.

- irrelevant/relevant

- 17.

- means a lot to me/means nothing to me

- 18.

- valuable/worthless

- 19.

- matters/does not matter

- 20.

- non-exciting/exciting

- 21.

- appealing/unappealing

- 22.

- essential/non-essential

- 23.

- significant/insignificant.

References

- Flis, S. The Rise of Cause Marketing. 21 February 2020. Available online: https://www.business2community.com/social-business/the-rise-of-cause-marketing-02286159 (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Edelman. Edelman Earned Brand Global Report. 2018. Available online: https://www.edelman.com/sites/g/files/aatuss191/files/2018-10/2018_Edelman_Earned_Brand_Global_Report.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Cone Communication. Porter Novelli/Cone Gen Z Purpose Study. 2019. Available online: https://www.conecomm.com/research-blog/cone-gen-z-purpose-study (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- IEG. IEG Sponsorship Report 2018: What Sponsors Want and Where Dollars Will Go in 2018. 2018. Available online: www.sponsorship.com (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Varadarajan, P.R.; Menon, A. Cause-related marketing: A co-alignment of marketing strategy and corporate philanthropy. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 58–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kotler, P.; Lee, N. Best of Breed: When It Comes to Gaining a Market Edge While Supporting a Social Cause, “Corporate Social Marketing” Leads the Pack. Soc. Mark. Q. 2005, 11, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lii, Y.-S.; Lee, M. Doing Right Leads to Doing Well: When the Type of CSR and Reputation Interact to Affect Consumer Evaluations of the Firm. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 105, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, C.N.; Katsikeas, C.S.; Morgan, N.A. “Greening” the Marketing Mix: Do Firms Do It and Does It Pay Off? J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2013, 41, 151–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsikeas, C.S.; Leonidou, C.N.; Zeriti, A. Eco-Friendly Product Development Strategy: Antecedents, Outcomes, and Contingent Effects. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2016, 44, 660–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bhattacharya, C.; Sen, S. Consumer–Company Identification: A Framework for Understanding Consumers’ Relationships with Companies. J. Mark. 2003, 67, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Crisafulli, B.; Quamina, L.T. How intensity of cause-related marketing guilt appeals influences consumers: The roles of company motives and consumer identification with the brand. J. Advert. Res. 2019, 60, 148–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisafulli, B.; Singh, J.; Quamina, L.T. Tackling Global Challenges Through Cause-Related Marketing: How Brands Should Promote Their Support to Social Causes. 2019. Available online: https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/27054/1/Best%20Practice%20case_Guilt%20Appeals%20in%20Cause%20Marketing_Accepted%2015%2003%2019.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Harrington, J. When Good Campaigns Go Bad: Six Recent Clangers. 2018. Available online: www.prweek.com/article/1491434/when-good-campaigns-go-bad-six-recent-clangers (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Chang, C.-T.; Cheng, Z.H. Tugging on heartstrings: Shopping orientation, mind-set, and consumer responses to cause-related marketing. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 127, 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-E.; Johnson, K.K.P. The Impact of Moral Emotions on Cause-Related Marketing Campaigns: A Cross-Cultural Examination. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 112, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabri, O. The Detrimental Effect of Cause-Related Marketing Parodies. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 151, 517–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladero, M.M.G.; Casquet, C.G.; Singh, J. Understanding factors influencing consumer attitudes toward cause-related marketing. Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Mark. 2015, 20, 52–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fries, A.J. The effects of cause-related marketing campaign characteristics—A literature review. Mark.-J. Res. Manag. 2010, 6, 145–157. [Google Scholar]

- Nejati, M. Successful cause-related marketing. Strateg. Dir. 2014, 30, 35–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Kim, J. How spatial distance and message strategy in cause-related marketing ads influence consumers’ ad believability and attitudes. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Trent, E.S.; Sullivan, P.M.; Matiru, G.N. Cause-related marketing: How generation Y responds. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2003, 31, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhamme, J.; Lindgreen, A.; Reast, J.; Van Popering, N. To do well by doing good: Improving corporate image through cause-related marketing. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 109, 259–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Saleme, P.; Pang, B.; Durl, J.; Xu, Z. A Systematic Review of Experimental Studies Investigating the Effect of Cause-Related Marketing on Consumer Purchase Intention. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strizhakova, Y.; Coulter, R.A. Spatial Distance Construal Perspectives on Cause-Related Marketing: The Importance of Nationalism in Russia. J. Int. Mark. 2019, 27, 38–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travers, M. Cultural Psychology Research Suggests the U.S. May Be Less Individualistic after Coronavirus Pandemic. Forbes. 23 March 2020. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/traversmark/2020/03/23/what-will-the-post-covid-19-world-look-like-lessons-from-cultural-psychology/#354b79073f58 (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Migliore, G.; Rizzo, G.; Schifani, G.; Quatrosi, G.; Vetri, L.; Testa, R. Ethnocentrism Effects on Consumers’ Behavior during COVID-19 Pandemic. Economies 2021, 9, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenblatt, P.C. Origins and effects of group ethnocentrism and nationalism. J. Confl. Resolut. 1964, 8, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siamagka, N.-T.; Balabanis, G. Revisiting consumer ethnocentrism: Review, reconceptualization, and empirical testing. J. Int. Mark. 2015, 23, 66–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Končar, J.; Marić, R.; Vukmirović, G.; Vučenović, S. Sustainability of Food Placement in Retailing during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walden, M.; Yang, S. As Coronavirus Sparks Anti-Chinese Racism, Xenophobia Rises in China Itself. ABC News, 14 April 2020. Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-04-09/coronavirus-intensifies-anti-foreigner-sentiment-in-china/12128224(accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Rich, M. As Coronavirus Spreads, so Does Anti-Chinese Sentiment. The New York Times, 13 February 2020. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/30/world/asia/coronavirus-chinese-racism.html(accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Shimp, T.A.; Sharma, S. Consumer ethnocentrism: Construction and validation of the CETSCALE. J. Mark. Res. 1987, 24, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Verlegh, P.W.J. Home country bias in product evaluation: The complementary roles of economic and socio-psychological motives. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2007, 38, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Shimp, T.A.; Shin, J. Consumer ethnocentrism: A test of antecedents and moderators. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1995, 23, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H. Social identity and intergroup behavior. Soc. Sci. Inf. 1974, 13, 65–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In Political Psychology: Key Readings; Jost, J.T., Ed.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 276–293. [Google Scholar]

- La Ferle, C.; Kuber, G.; Edwards, S.M. Factors impacting responses to cause-related marketing in India and the United States: Novelty, altruistic motives, and company origin. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Scodellaro, A.; Pang, B.; Lo, H.Y.; Xu, Z. Attribution and Effectiveness of Cause-Related Marketing: The Interplay between Cause–Brand Fit and Corporate Reputation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pracejus, J.W.; Olsen, G.D. The role of brand/cause fit in the effectiveness of cause-related marketing campaigns. J. Bus. Res. 2004, 57, 635–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendini, M.; Peter, P.C.; Gibbert, M. The dual-process model of similarity in cause-related marketing: How taxonomic versus thematic partnerships reduce skepticism and increase purchase willingness. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 91, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafferty, B.A. The relevance of fit in a cause–brand alliance when consumers evaluate corporate credibility. J. Bus. Res. 2007, 60, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zasuwa, G. Do the ends justify the means? How altruistic values moderate consumer responses to corporate social initiatives. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3714–3719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, W.-Y.; Song, H.-S.; Kim, D.-H.; Byon, K.K. Cause-Related Marketing and Purchase Intention toward Team-Licensed Products: Moderating Effects of Sport Consumers’ Altruism. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yen, G.F.; Yang, H.T. Does Consumer Empathy Influence Consumer Responses to Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility? The Dual Mediation of Moral Identity. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lerro, M.; Raimondo, M.; Stanco, M.; Nazzaro, C.; Marotta, G. Cause Related Marketing among Millennial Consumers: The Role of Trust and Loyalty in the Food Industry. Sustainability 2019, 11, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Strahilevitz, M.; Myers, J.G. Donations to Charity as Purchase Incentives: How Well They Work May Depend on What You Are Trying to Sell. J. Consum. Res. 1998, 24, 434–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, T.; Wang, S.S. Cause-Related Marketing in the Telecom Sector: Understanding the Dynamics among Environmental Values, Cause-Brand Fit, and Product Type. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.; Liu, H. Goodwill hunting? Influences of product-cause fit, product type, and donation level in cause-related marketing. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2012, 30, 634–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, D.; Kim, J.A.; Doh, S.J. The Dual Processing of Donation Size in Cause-Related Marketing (CRM): The Moderating Roles of Construal Level and Emoticons. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cornwell, T.; Coote, L.V. Corporate sponsorship of a cause: The role of identification in purchase intent. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demetriou, M.; Papasolomou, I.; Vrontis, D. Cause-related marketing: Building the corporate image while supporting worthwhile causes. J. Brand Manag. 2009, 17, 266–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen, P.S.; Mohr, L.A.; Webb, D.J. Charitable programs and the retailer: Do they mix? J. Retail. 2000, 76, 393–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, J.K.; Stutts, M.A.; Patterson, L.T. Tactical considerations for the effective use of cause-related marketing. J. Appl. Bus. Res. 1991, 7, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grau, S.L.; Folse, J.A.G. Cause-related marketing: The influence of donation proximity and message-framing cues on the less-involved consumer. J. Advert. 2007, 36, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Du, L.; Li, J. Cause’s attributes influencing consumer’s purchasing intention: Empirical evidence from China. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2008, 20, 363–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, J.K.; Patterson, L.T.; Stutts, M.A. Consumer perceptions of organizations that use cause-related marketing. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1992, 20, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schons, L.M.; Cadogan, J.; Tsakona, R.J. Should charity begin at home? An empirical investigation of consumers’ responses to companies’ varying geographic allocations of donation budgets. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 144, 559–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankarmahesh, M.N. Consumer ethnocentrism: An integrative review of its antecedents and consequences. Int. Mark. Rev. 2006, 23, 146–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balabanis, G.; Diamantopoulos, A. Domestic country bias, country-of-origin effects, and consumer ethnocentrism: A multidimensional unfolding approach. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2004, 32, 80–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeugner-Roth, K.P.; Žabkar, V.; Diamantopoulos, A. Consumer ethnocentrism, national identity, and consumer cosmopolitanism as drivers of consumer behavior: A social identity theory perspective. J. Int. Mark. 2015, 23, 25–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazquez-Resino, J.; Gutierrez-Broncano, S.; Jimenez-Estevez, P.; Perez-Jimenez, I. The effects of ethnocentrism on product evaluation and purchase intention: The case of extra virgin olive oil. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, T.; Kwon, I.G. Globalization and reluctant buyers. Int. Mark. Rev. 2002, 19, 663–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balabanis, G.; Siamagka, N.T. Inconsistencies in the behavioural effects of consumer ethnocentrism. Int. Mark. Rev. 2017, 34, 166–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Strizhakova, Y.; Coulter, R.A. Drivers of Local Relative to Global Brand Purchases: A Contingency Approach. J. Int. Mark. 2015, 23, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.M.; Nam, H. How inter-country similarities moderate the effects of consumer ethnocentrism and cosmopolitanism in out-group country perceptions. Int. Mark. Rev. 2019, 37, 130–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, M.A. Social Identity Theory. In Contemporary Social Psychological Theories; Burke, P.J., Ed.; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 2006; pp. 111–136. [Google Scholar]

- Balabanis, G.; Diamantopoulos, A. Consumer Xenocentrism as Determinant of Foreign Product Preference: A System Justification Perspective. J. Int. Mark. 2016, 24, 58–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumner, W.G. Folkways: A Study of the Sociological Importance of Usages, Manners, Customs, Mores and Morals; Ginn and Co.: Boston, MA, USA, 1906. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, A. Activating the self-importance of consumer selves: Exploring identity salience effects on judgements. J. Consum. Res. 2004, 31, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haslam, S.A. Psychology in Organizations: The Social Identity Approach; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Van Knippenberg, D. Work Motivation and Performance: A Social Identity Perspective. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 49, 357–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Zhu, W.; Gouran, D.; Kolo, O. Moral Identity centrality and cause related marketing. The moderating effects of brand social responsibility image and emotional brand attachment. Eur. J. Mark. 2015, 50, 236–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquino, K.; Freeman, D.; Reed, A.I.I.; Lim, V.K.G.; Felps, W. Testing a social cognitive model of moral behavior: The interactive influence of situation and moral identity centrality. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 97, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirmani, A. The self and the brand. J. Consum. Psychol. 2009, 19, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skitka, L.J. Of different minds: An accessible identity model of justice reasoning. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2003, 7, 286–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter, C.O.L.H.; Outlaw, R.; Gale, J.P.; Cho, T.S. The Use of Online Panel Data in Management Research: A Review and Recommendations. J. Manag. 2019, 45, 319–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Butler, P. UK hunger Survey to Measure Food Insecurity. The Guardian, 27 February 2019. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2019/feb/27/government-to-launch-uk-food-insecurity-index(accessed on 30 November 2021).

- End Hunger UK. Why End UK hunger? The Case from Public Opinion. 2019. Available online: https://www.endhungeruk.org/2019/12/16/public/ (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Lafferty, B.A. Cause-Related Marketing: Does the Cause Make a Difference in Consumers’ Attitudes and Purchase Intentions Toward the Product? Working Paper; Department of Marketing, Florida State University: Tallahassee, FL, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Office for National Statistics (ONS). Population of the UK by Country of Birth and Nationality. 2021. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/internationalmigration/datasets/populationoftheunitedkingdombycountryofbirthandnationality (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Chang, C.-T. To donate or not to donate? Product characteristics and framing effects of cause-related marketing on consumer purchase behavior. Psychol. Mark. 2008, 25, 1089–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folse, J.A.G.; Niedrich, R.W.; Grau, S.L. Cause-Relating Marketing: The Effects of Purchase Quantity and Firm Donation Amount on Consumer Inferences and Participation Intentions. J. Retail. 2010, 86, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putrevu, S.; Lord, K.R. Comparative and non-comparative advertising: Attitudinal effects under cognitive and affective involvement conditions. J. Advert. 1994, 23, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis, 5th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, F.D. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, P.A.O.; Silva, S.C. The role of consumer-cause identification and attitude in the intention to purchase cause related products. Int. Mark. Rev. 2020, 37, 603–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Ang, T.; Liou, R.-S. Does the global vs. local scope matter? Contingencies of cause-related marketing in a developed market. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 108, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.C. Towards a Cognitive Redefinition of the Social Group. In Social Identity and Intergroup Relations; Tajfel, H., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010; pp. 15–40. [Google Scholar]

- Marquis, C.; Glynn, M.A.; Davis, G.F. Community isomorphism and corporate social action. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 925–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Development Initiatives. Global Humanitarian Assistance Report. 2018. Available online: http://devinit.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/GHA-Report-2018.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Riefler, P.; Diamantopoulos, A. Consumer animosity: A literature review and a reconsideration of its measurement. Int. Mark. Rev. 2007, 24, 87–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, G.; Tu, H.; Cheng, B. Interactive effect of consumer affinity and consumer ethnocentrism on product trust and willingness-to-buy: A moderated-mediation model. J. Consum. Mark. 2018, 35, 688–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strizhakova, Y.; Coulter, R.A.; Price, L. The fresh start mindset: A cross-national investigation and implications for environmentally friendly global brands. J. Int. Mark. 2021, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trautwein, S.; Lindenmeier, J. The effect of affective response to corporate social irresponsibility on consumer resistance behaviour: Validation of a dual channel model. J. Mark. Manag. 2019, 35, 253–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Crilly, D.; Ni, N.; Jiang, Y. Do-no-harm versus do-good social responsibility: Attributional thinking and the liability of foreignness. Strateg. Manag. J. 2016, 37, 1316–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, T.P.; Loraas, T.M. Using Qualtrics Panels to Source External Auditors: A Replication Study. J. Inf. Syst. 2019, 33, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howie, K.M.; Yang, L.; Vitell, S.J.; Bush, V.; Vorhies, D. Consumer Participation in Cause-Related Marketing: An Examination of Effort Demands and Defensive Denial. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 147, 679–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christofi, M.; Vrontis, D.; Leonidou, E.; Thrassou, A. Customer engagement through choice in cause-related marketing: A potential for global competitiveness. Int. Mark. Rev. 2018, 37, 621–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).