Does the Past Affect the Future? An Analysis of Consumers’ Dining Intentions towards Green Restaurants in the UK

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

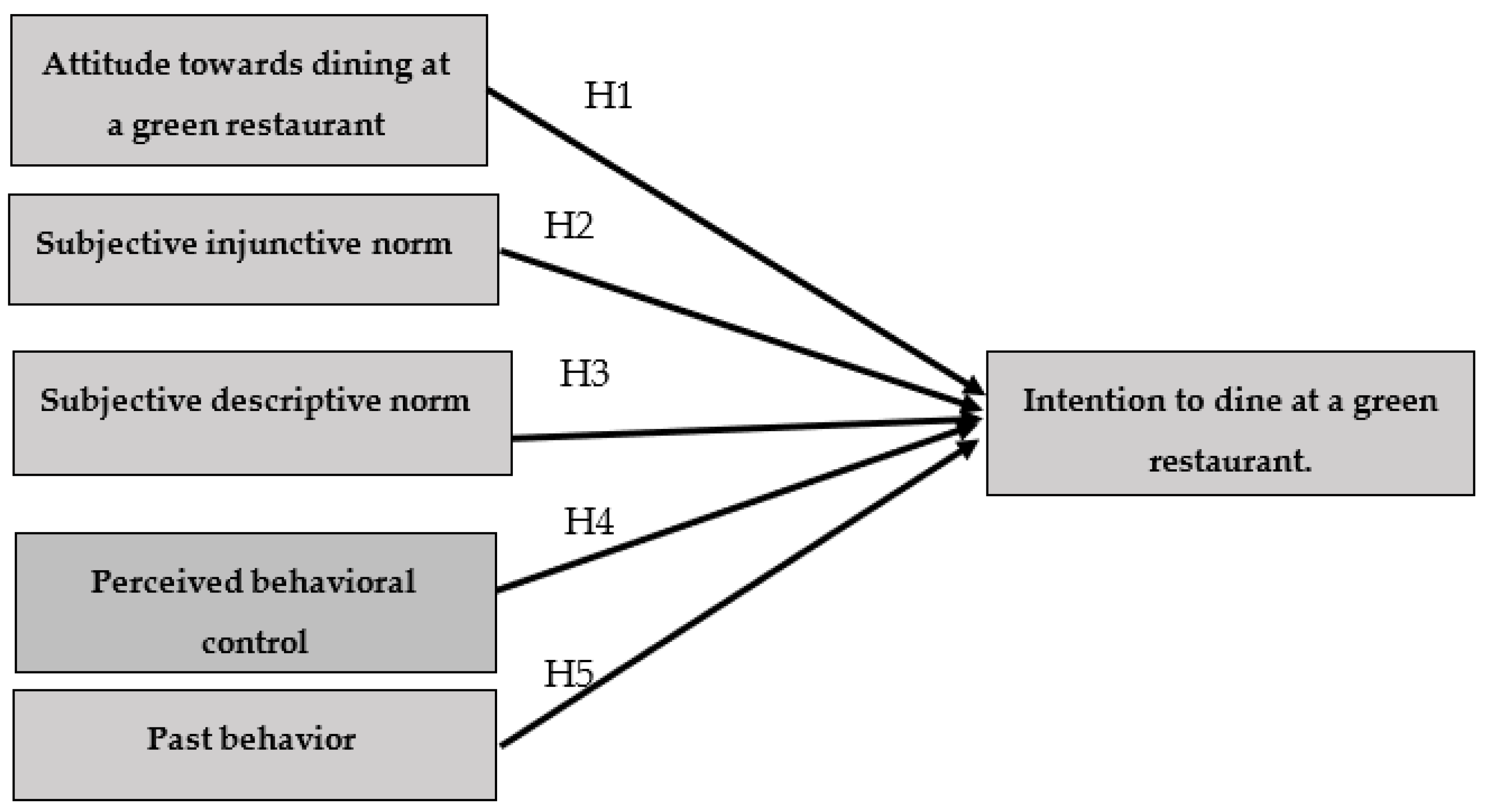

2.1. The Theory of Planned Behavior

2.2. Demographic Characteristics

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Questionnaire Development

3.2. Sampling and Data Collection

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Hypotheses Results

4.2. The Demographics Effect

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Limitations and Directions for Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, K.-N.; Hu, C.; Lin, M.-C.; Tsai, T.-I.; Xiao, Q. Brand knowledge and non-financial brand performance in the green restaurants: Mediating effect of brand attitude. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 89, 102566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Climate Change 2021—Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability: Regional Aspects; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Environmental Programme. The Sustainable Tourism Programme. Available online: https://stories.undp.org/categories/sustainable-tourism?year=2020 (accessed on 9 November 2021).

- Fang, Y.; Yin, J.; Wu, B. Climate change and tourism: A scientometric analysis using CiteSpace. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 108–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaali, N.; Al Marzouqi, A.; Dahabreh, F.; Mouzaek, E.; Portal, R.; Salloum, S. The Impact of Adopting Corporate Governance Strategic Performance in the Tourism Sector: A Case Study in the Kingdom of Bahrain. J. Leg. Ethical Regul. 2021, 24, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Fennell, D.A.; Bowyer, E. Tourism and sustainable transformation: A discussion and application to tourism food consumption. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2020, 45, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshurideh, M.; Kurdi, B.A.; Shaltoni, A.M.; Ghuff, S.S. Determinants of pro-environmental behavior in the context of emerging economies. Int. J. Sustain. Soc. 2019, 11, 257–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, T.K.; Kumar, A.; Jakhar, S.; Luthra, S.; Garza-Reyes, J.A.; Kazancoglu, I.; Nayak, S.S. Social and environmental sustainability model on consumers’ altruism, green purchase intention, green brand loyalty and evangelism. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 243, 118575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alameeri, K.; Alshurideh, M.; Al Kurdi, B.; Salloum, S.A. The Effect of Work Environment Happiness on Employee Leadership. In International Conference on Advanced Intelligent Systems and Informatics; Springer: Cario, Egypt, 2020; pp. 668–680. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H. Theory of green purchase behavior (TGPB): A new theory for sustainable consumption of green hotel and green restaurant products. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 2815–2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, N. Luxury restaurants’ risks when implementing new environmentally friendly programs–evidence from luxury restaurants in Taiwan. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 2409–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namkung, Y.; Jang, S. Are consumers willing to pay more for green practices at restaurants? J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2017, 41, 329–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimri, R.; Dharmesti, M.; Arcodia, C.; Mahshi, R. UK consumers’ ethical beliefs towards dining at green restaurants: A qualitative evaluation. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 48, 572–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento, C.V.; El Hanandeh, A. Customers’ perceptions and expectations of environmentally sustainable restaurant and the development of green index: The case of the Gold Coast, Australia. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2018, 15, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K. Consumer Skepticism about Quick Service Restaurants’ Corporate Social Responsibility Activities. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2020, 23, 417–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Hall, C.M. Can sustainable restaurant practices enhance customer loyalty? The roles of value theory and environmental concerns. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 43, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Predicting and Changing Behavior: The Reasoned Action Approach; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, J.; Modi, A.; Patel, J. Predicting green product consumption using theory of planned behavior and reasoned action. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 29, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Wang, S.; Li, J.; Li, H. Application of the extended theory of planned behavior to understand individual’s energy saving behavior in workplaces. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimri, R.; Patiar, A.; Kensbock, S.; Jin, X. Consumers’ intention to stay in green hotels in Australia: Theorization and implications. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2020, 44, 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.Y.; Chung, J.Y.; Kim, Y. Effects of Environmentally Friendly Perceptions on Customers’ Intentions to Visit Environmentally Friendly Restaurants: An Extended Theory of Planned Behavior. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 20, 599–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.-J. Investigating beliefs, attitudes, and intentions regarding green restaurant patronage: An application of the extended theory of planned behavior with moderating effects of gender and age. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 92, 102727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, H.; Dijkstra, M.; Kuhlman, P. Self-efficacy: The third factor besides attitude and subjective norm as a predictor of behavioral intentions. Health Educ. Res. 1988, 3, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towler, G.; Shepherd, R. Modification of Fishbein and Ajzen’s theory of reasoned action to predict chip consumption. Food Qual. Prefer. 1991, 3, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hsu, T.; Sheu, C. Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior to green hotel choice: Testing the effect of environmental friendly activities. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myung, E.; McClaren, A.; Li, L. Environmentally related research in scholarly hospitality journals: Current status and future opportunities. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 1264–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E.C.L.; Nimri, R.; Lai, M.Y. Uncovering the critical drivers of solo holiday attitudes and intentions. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2022, 41, 100913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior: Reactions and reflections. Psychol. Health 2011, 26, 1113–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, L.-l. Influencing Factors on Creative Tourists’ Revisiting Intentions: The Roles Of Motivation, Experience And Perceived Value. Ph.D. Thesis, Clemson University, Clemson, SC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, T.; Hsu, C.H. Theory of planned behavior: Potential travelers from China. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2004, 28, 463–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, L. The theory of planned behavior and the impact of past behavior. Int. Bus. Econ. Res. J. 2011, 10, 91. [Google Scholar]

- Ouellette, J.A.; Wood, W. Habit and intention in everyday life: The multiple processes by which past behavior predicts future behavior. Psychol. Bull. 1998, 124, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ritchie, B.W. Understanding accommodation managers’ crisis planning intention: An application of the theory of planned behavior. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1057–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Kim, Y. An investigation of green hotel customers’ decision formation: Developing an extended model of the theory of planned behavior. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 29, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namkung, Y.; Jang, S. Effects of restaurant green practices on brand equity formation: Do green practices really matter? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 33, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F.; Moskwa, E.; Wijesinghe, G. How sustainable is sustainable hospitality research? A review of sustainable restaurant literature from 1991 to 2015. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 22, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Lee, K.; Fairhurst, A. The review of “green” research in hospitality, 2000–2014: Current trends and future research directions. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 226–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leeuw, A.; Valois, P.; Ajzen, I.; Schmidt, P. Using the theory of planned behavior to identify key beliefs underlying pro-environmental behavior in high-school students: Implications for educational interventions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 42, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Y.M.; Wu, K.S.; Liu, H.H. Integrating Altruism and the Theory of Planned Behavior to Predict Patronage Intention of a Green Hotel. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2015, 39, 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.; Huang, S. An Extension of the Theory of Planned Behavior Model for Tourists. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2010, 36, 390–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M.S.; Chatzisarantis, N.L.; Barkoukis, V.; Wang, J.C.; Hein, V.; Pihu, M.; Soós, I.; Karsai, I. Cross-cultural generalizability of the theory of planned behavior among young people in a physical activity context. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2007, 29, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research Reading; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Ryu, K.; Jang, S. Intention to experience local cuisine in a travel destination: The modified theory of reasoned action. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2006, 30, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiPietro, R.B.; Gregory, S.; Jackson, A. Going green in quick-service restaurants: Customer perceptions and intentions. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2013, 14, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berezan, O.; Millar, M.; Raab, C. Sustainable Hotel Practices and Guest Satisfaction Levels. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2014, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.-Y.; Lehto, X.Y.; Morrison, A.M. Gender differences in online travel information search: Implications for marketing communications on the internet. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolau, J.L.; Guix, M.; Hernandez-Maskivker, G.; Molenkamp, N. Millennials’ willingness to pay for green restaurants. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 90, 102601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hsu, T.; Lee, A.; Sheu, C. Are lodging customers ready to go green? An examination of attitudes, demographics, and eco-friendly intentions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S. The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Collingridge, D. Validating a questionnaire. Retrieved Febr. 2014, 25, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Netemeyer, R.; Bearden, W.; Sharma, S. Scaling Procedures: Issues and Applications; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Van Selm, M.; Jankowski, N.W. Conducting online surveys. Qual. Quant. 2006, 40, 435–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.J.A.; Busser, J.A. Impact of service climate and psychological capital on employee engagement: The role of organizational hierarchy. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 75, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, L.H.; Tsai, C.H.; Yeh, S.S. Evaluation of Green Hotel Guests’ Behavioral Intention. Adv. Hosp. Leis. 2014, 10, 75–89. [Google Scholar]

- Nimri, R.; Patiar, A.; Kensbock, S. A green step forward: Eliciting consumers’ purchasing decisions regarding green hotel accommodation in Australia. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2017, 33, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al kurdi, B. Healthy-Food Choice and Purchasing Behavior Analysis: An Exploratory Study of Families in the UK. PhD. Thesis, Durham University, Durham, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Alshurideh, M.T. Do we care about what we buy or eat? A practical study of the healthy foods eaten by Jordanian youth. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2014, 9, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joghee, S.; Alzoubi, H.M.; Alshurideh, M.; Al Kurdi, B. The Role of Business Intelligence Systems on Green Supply Chain Management: Empirical Analysis of FMCG in the UAE. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Computer Vision, Settat, Morocco, 28–30 June 2021; Springer: Settat, Morocco, 2021; pp. 539–552. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G. Dimensionalizing Cultures: The Hofstede Model in Context. Online Read. Psychol. Cult. 2011, 2, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Measure | ATT | SIN | SDN | PBC | PB | INT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATT | 1.000 | |||||

| SIN | 0.077 (0.006) | 1.000 | ||||

| SDN | 0.335 (0.112) | 0.647 (0.419) | 1.000 | |||

| PBC | 0.379 (0.143) | 0.031 (0.001) | 0.242 (0.059) | 1.000 | ||

| PB | 0.145 (0.021) | 0.077 (0.006) | 0.269 (0.072) | 0.463 (0.214) | 1.000 | |

| INT | 0.187 (0.035) | 0.154 (0.024) | 0.306 (0.0936) | 0.682 (0.465) | 0.631 (0.398) | 1.000 |

| Mean | 5.45 | 4.78 | 4.92 | 5.83 | 5.26 | 5.31 |

| SD | 0.923 | 1.071 | 1.187 | 1.235 | 0.982 | 1.288 |

| CR | 0.943 | 0.603 | 0.909 | 0.807 | 0.728 | 0.768 |

| AVE | 0.718 | 0.611 | 0.923 | 0.789 | 0.643 | 0.741 |

| Paths | Coefficient | T-Value | Hypotheses |

|---|---|---|---|

| ATT → INT | 0.32 | 6.53 | H1: Supported |

| SIN → INT | 0.04 | 0.68 | H2: Not Supported |

| SDN → INT | 0.12 | 2.12 | H3: Supported |

| PBC → INT | 0.52 | 18.19 | H4: Supported |

| PB → INT | 0.16 | 3.76 | H5: Supported |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shishan, F.; Mahshi, R.; Al Kurdi, B.; Alotoum, F.J.; Alshurideh, M.T. Does the Past Affect the Future? An Analysis of Consumers’ Dining Intentions towards Green Restaurants in the UK. Sustainability 2022, 14, 276. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010276

Shishan F, Mahshi R, Al Kurdi B, Alotoum FJ, Alshurideh MT. Does the Past Affect the Future? An Analysis of Consumers’ Dining Intentions towards Green Restaurants in the UK. Sustainability. 2022; 14(1):276. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010276

Chicago/Turabian StyleShishan, Farah, Ricardo Mahshi, Brween Al Kurdi, Firas Jamil Alotoum, and Muhammad Turki Alshurideh. 2022. "Does the Past Affect the Future? An Analysis of Consumers’ Dining Intentions towards Green Restaurants in the UK" Sustainability 14, no. 1: 276. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010276

APA StyleShishan, F., Mahshi, R., Al Kurdi, B., Alotoum, F. J., & Alshurideh, M. T. (2022). Does the Past Affect the Future? An Analysis of Consumers’ Dining Intentions towards Green Restaurants in the UK. Sustainability, 14(1), 276. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010276