Grey’s Anatomy: Gender Differences in Specialty Choice for Medical Students in China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

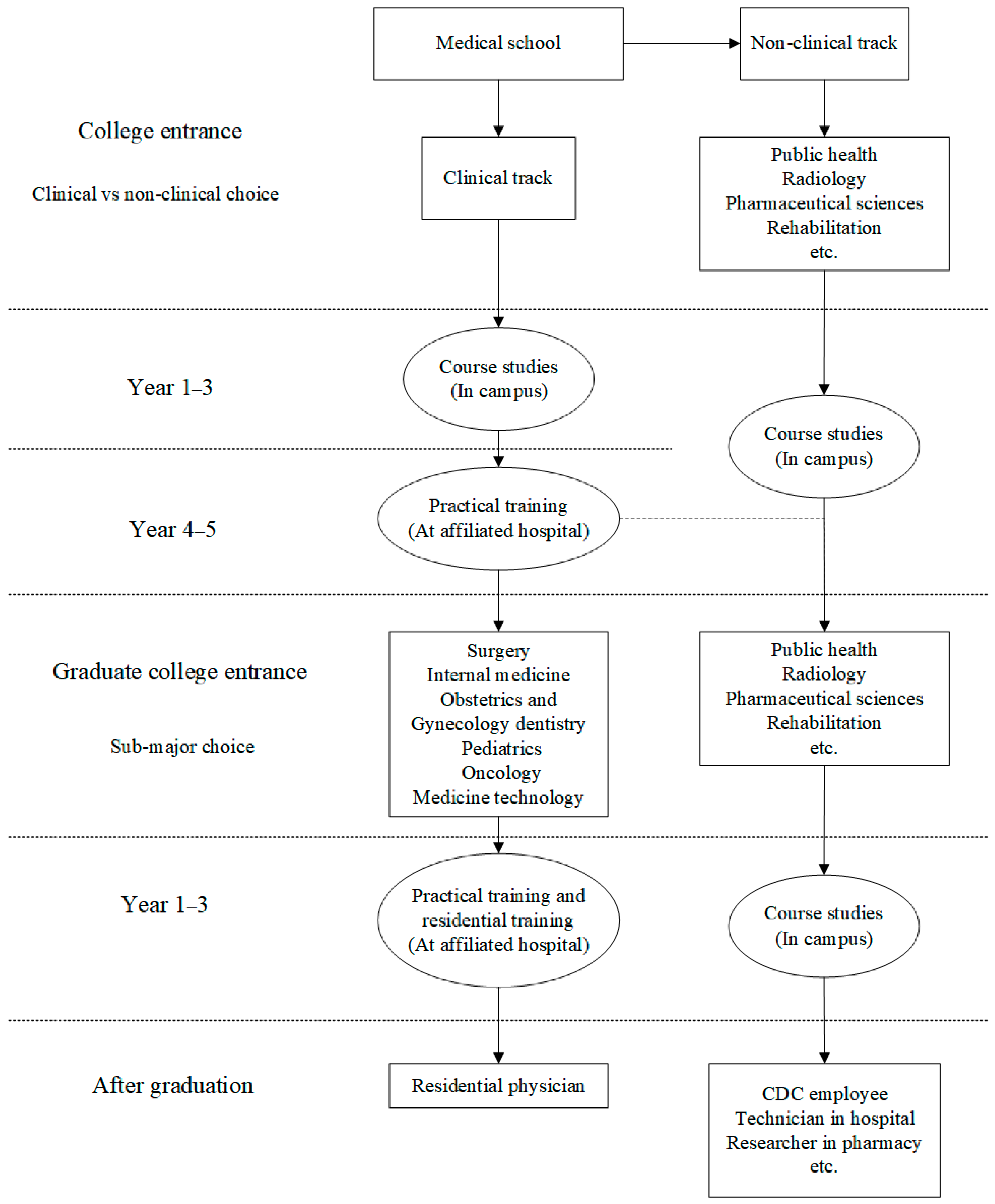

1.1. Medical Education in China

1.2. A Brief Review of Literature on Gender Differences in Major Choice

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

- (1)

- Physical Demand

- (2)

- Anticipated Discrimination

- (3)

- Work-Life Balance

- (4)

- Peer Effects and Role Models

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C

| Questions | No. of Answers | No. of Viewers |

|---|---|---|

| Is it really bad for a woman to be a surgeon? | 21 | 72,133 |

| Is surgery for girls? | 11 | 27,171 |

| Is it good for girls to study surgery? | 5 | 8977 |

| Why do you rarely see female doctors in general surgery? | 28 | 192,834 |

| Is surgery suitable for girls? | 18 | 120,219 |

| Is it really impossible for a female student to take the medical examination for cardiac surgery? | 10 | 8511 |

| Is it really impossible for a girl to study cardiac surgery in the medical examination? | 6 | 1322 |

| Is it impossible for a woman to work in surgery? | 1 | 540 |

| Why are there so few female surgeons when more and more women are studying surgery? | 5 | 5409 |

Appendix D

| Panel A | Standardized Score of Theory Course | |||

| Internal | Surgery | Obstetrics | Pediatrics | |

| Female | 0.712 *** | 0.748 *** | 0.713 *** | 0.793 *** |

| (0.075) | (0.085) | (0.081) | (0.082) | |

| Observations | 478 | 482 | 481 | 481 |

| R2 | 0.467 | 0.282 | 0.392 | 0.348 |

| Panel B | Standardized Score of Practice Course | |||

| Internal | Surgery | Obstetrics | Pediatrics | |

| Female | 0.485 *** | 0.301 *** | 0.608 *** | 0.720 *** |

| (0.086) | (0.058) | (0.084) | (0.083) | |

| Observations | 481 | 481 | 478 | 479 |

| R2 | 0.288 | 0.699 | 0.381 | 0.295 |

Appendix E

References

- Bertrand, M. Gender in the Twenty-First Century. AEA Pap. Proc. 2020, 110, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves-Sorenson, C.; Snyder, J. The gender earnings gap for physicians and its increase over time. Econ. Lett. 2012, 116, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguli, I.; Sheridan, B.; Gray, J.; Chernew, M.; Rosenthal, M.B.; Neprash, H. Physician Work Hours and the Gender Pay Gap —Evidence from Primary Care. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1349–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoff, T.; Lee, D.-R. The Gender Pay Gap in Medicine: A Systematic Review. Health Care Manag. Rev. 2020, 46, E37–E49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigh, J.P.; Tancredi, D.; Jerant, A.; Romano, P.S.; Kravitz, R.L. Lifetime Earnings for Physicians across Specialties. Med. Care 2012, 50, 1093–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kane, L. Medscape Physician Compensation Report 2021. 2021. Available online: https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2021-compensation-overview-6013761 (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Zhang, C.; Liu, Y. The salary of physicians in Chinese public tertiary hospitals: A national cross-sectional and follow-up study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xepoleas, M.D.; Munabi, N.C.O.; Auslander, A.; Magee, W.P.; Yao, C.A. The experiences of female surgeons around the world: A scoping review. Hum. Resour. Health 2020, 18, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AAMC. 2020 Physician Specialty Data Report. 2020. Available online: https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/interactive-data/active-physicians-sex-and-specialty-2019 (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Dickson, L. Race and gender differences in college major choice. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 2010, 627, 108–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, B. College major choice and the gender gap. J. Hum. Resour. 2013, 48, 545–595. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, C.; Tsang, M.C.; Ding, X. Gender disparities in science and engineering in Chinese universities. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2010, 29, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, H. The Status of Women in STEM in Higher Education: A Review of the Literature 2007–2017. Sci. Technol. Libr. 2017, 36, 235–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. Why students choose STEM majors: Motivation, high school learning, and postsecondary context of support. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2013, 50, 1081–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ost, B. The role of peers and grades in determining major persistence in the sciences. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2010, 29, 923–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justman, M.; Méndez, S.J. Gendered choices of STEM subjects for matriculation are not driven by prior differences in mathematical achievement. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2018, 64, 282–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Main, J.B.; Ost, B. The Impact of Letter Grades on Student Effort, Course Selection, and Major Choice: A Regression-Discontinuity Analysis. J. Econ. Educ. 2014, 45, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaney, J.M.; Devereux, P.J. Understanding gender differences in STEM: Evidence from college applications. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2019, 72, 219–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loyalka, P.K.; Maani, M.; Qu, Y.; Sylvia, S. Absolute versus Comparative Advantage: Consequences for Gender Gaps in STEM and College Access. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2908533 (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Card, D.; Payne, A.A. High School Choices and the Gender Gap in Stem. Econ. Inq. 2020, 59, 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melak, A.; Singh, S. Women’s Participation and Factors Affecting Their Academic Performance in Engineering and Technology Education: A Study of Ethiopia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, S.; Ginther, D. Women and STEM; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; No. w23525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altonji, J.G.; Arcidiacono, P.; Maurel, A. The Analysis of Field Choice in College and Graduate School: Determinants and Wage Effects. Handb. Econ. Educ. 2015, 5, 305–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, M.C.; Goldhaber, D.; Huntington-Klein, N. Do completed college majors respond to changes in wages? Econ. Educ. Rev. 2015, 49, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Han, L.; Winters, J.V. Industry Fluctuations and College Major Choices: Evidence from an Energy Boom and Bust. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2020, 77, 101996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montmarquette, C.; Cannings, K.; Mahseredjian, S. How do young people choose college majors? Econ. Educ. Rev. 2002, 21, 543–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arcidiacono, P.; Hotz, V.J.; Maurel, A.; Romano, T. Ex Ante Returns and Occupational Choice. J. Polit. Econ. 2020, 128, 4475–4522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuben, E.; Sapienza, P.; Zingales, L. How stereotypes impair women’s careers in science. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 4403–4408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Charness, G.; Cobo-Reyes, R.; Meraglia, S.; Sánchez, Á. Anticipated Discrimination, Choices, and Performance: Experimental Evidence. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2020, 127, 103473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valk, R.; Srinivasan, V. Work–family balance of Indian women software professionals: A qualitative study. IIMB Manag. Rev. 2011, 23, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Minnotte, K.L.; Pedersen, D.E. Department Environment and Work-to-Life Conflict among Faculty in the STEM Fields. J. Fam. Issues 2019, 40, 1299–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jean, V.A.; Payne, S.C.; Thompson, R.J. Women in STEM: Family-Related Challenges and Initiatives. In Gender and the Work-Family Experience; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 291–311. [Google Scholar]

- Bronson, M.A. Degrees Are Forever: Marriage, Educational Investment, and Lifecycle Labor Decisions of Men and Women. 2014, 2. (Working Paper). Available online: https://cmepr.gmu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/Bronson_Paper.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Mouganie, P.; Wang, Y. High-Performing Peers and Female STEM Choices in School. J. Labor Econ. 2020, 38, 805–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Riegle-Crumb, C.; Morton, K. Gendered Expectations: Examining How Peers Shape Female Students’ Intent to Pursue STEM Fields. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brenøe, A.A.; Zölitz, U. Exposure to More Female Peers Widens the Gender Gap in Stem Participation. J. Labor Econ. 2020, 38, 1009–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arcidiacono, P.; Nicholson, S. Peer effects in medical school. J. Public Econ. 2005, 89, 327–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Porter, C.; Serra, D. Gender Differences in the Choice of Major: The Importance of Female Role Models. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 2020, 12, 226–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, S.D.; Adelman, R.M.; Bodford, J.E.; Graudejus, O.; Okun, M.A.; Kwan, V.S.Y. The Effects of a Female Role Model on Academic Performance and Persistence of Women in STEM Courses. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2016, 38, 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, G.L.; Davis, W.K.; Yan, A.C.; Fantone, J.C., III. Following medical school graduates into practice: Residency directors’ assessments after the first year of residency. Acad. Med. 2000, 75, S15–S17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Case, S.M.; Swanson, D.B.; Ripkey, D.R.; Bowles, L.T.; Melnick, D.E. Performance of the class of 1994 in the new era of USMLE. Acad. Med. 1996, 71, S91–S93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krueger, P.M. Do women medical students outperform men in obstetrics and gynecology? Acad. Med. J. Assoc. Am. Med. Coll. 1998, 73, 101–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cullen, Z.; Perez-Truglia, R. The Old Boys’ Club: Schmoozing and the Gender Gap; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; No. w26530. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.; Cheng, T.C. How do gender differences in family responsibilities affect doctors’ labour supply? Evidence from Australian panel data. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 265, 113475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortés, P.; Pan, J. When Time Binds: Substitutes for Household Production, Returns to Working Long Hours, and the Skilled Gender Wage Gap. J. Labor Econ. 2019, 37, 351–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, M.C. When does gender matter? Gender differences in specialty choice among physicians. Work. Occup. 2011, 38, 221–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiligers, P.J. Gender differences in medical students’ motives and career choice. BMC Med. Educ. 2012, 12, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Clinic | ||

| Female | −0.049 *** | −0.047 *** | −0.107 *** |

| (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.019) | |

| Female * enrolled in 2005–2010 | 0.031 | ||

| (0.023) | |||

| Female * enrolled in 2010–2015 | 0.060 *** | ||

| (0.022) | |||

| Female * enrolled after 2015 | 0.115 *** | ||

| (0.023) | |||

| Master’s degree | −0.012 * | −0.012 * | |

| (0.007) | (0.007) | ||

| Enrollment year FE | No | Yes | Yes |

| Birth province FE | No | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 23,108 | 20,335 | 20,335 |

| R2 | 0.002 | 0.045 | 0.047 |

| Mean of Y | 0.385 | 0.401 | 0.401 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Surgery | ||

| Female | −0.490 *** | −0.497 *** | −0.521 *** |

| (0.008) | (0.009) | (0.020) | |

| Female * enrolled in 2005–2010 | −0.001 | ||

| (0.026) | |||

| Female * enrolled in 2010–2015 | 0.048 * | ||

| (0.026) | |||

| Female * enrolled after 2015 | 0.045 | ||

| (0.028) | |||

| Master’s degree | −0.046 *** | −0.047 *** | |

| (0.009) | (0.009) | ||

| Enrollment year FE | No | Yes | Yes |

| Birth province FE | No | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 8899 | 8146 | 8146 |

| R2 | 0.323 | 0.344 | 0.345 |

| Mean of Y | 0.239 | 0.239 | 0.239 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Surgery | ||

| Female | −0.633 *** | −0.640 *** | −0.643 *** |

| (0.035) | (0.044) | (0.043) | |

| Internal theory | −0.046 | −0.072 | |

| (0.035) | (0.050) | ||

| Surgery theory | 0.041 | 0.056 | |

| (0.029) | (0.042) | ||

| Obstetrics theory | −0.028 | −0.079 * | |

| (0.030) | (0.044) | ||

| Pediatrics theory | −0.007 | 0.024 | |

| (0.031) | (0.045) | ||

| Internal practice | 0.022 | 0.057 * | |

| (0.021) | (0.031) | ||

| Surgery practice | 0.039 | 0.039 | |

| (0.033) | (0.041) | ||

| Obstetrics practice | −0.025 | −0.015 | |

| (0.027) | (0.038) | ||

| Pediatrics practice | 0.026 | 0.066 ** | |

| (0.033) | (0.032) | ||

| Female * internal theory | 0.073 | ||

| (0.051) | |||

| Female * surgery theory | −0.026 | ||

| (0.053) | |||

| Female * obstetrics theory | 0.118 ** | ||

| (0.049) | |||

| Female * pediatrics theory | −0.089 * | ||

| (0.053) | |||

| Female * internal practice | −0.091 ** | ||

| (0.039) | |||

| Female * surgery practice | −0.004 | ||

| (0.040) | |||

| Female * obstetrics practice | −0.010 | ||

| (0.045) | |||

| Female * pediatrics practice | −0.090 * | ||

| (0.046) | |||

| Observations | 547 | 470 | 470 |

| R-squared | 0.461 | 0.485 | 0.508 |

| Mean of Y | 0.367 | 0.396 | 0.396 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shao, X.; Wang, T. Grey’s Anatomy: Gender Differences in Specialty Choice for Medical Students in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 230. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010230

Shao X, Wang T. Grey’s Anatomy: Gender Differences in Specialty Choice for Medical Students in China. Sustainability. 2022; 14(1):230. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010230

Chicago/Turabian StyleShao, Xiaofeng, and Tianyu Wang. 2022. "Grey’s Anatomy: Gender Differences in Specialty Choice for Medical Students in China" Sustainability 14, no. 1: 230. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010230

APA StyleShao, X., & Wang, T. (2022). Grey’s Anatomy: Gender Differences in Specialty Choice for Medical Students in China. Sustainability, 14(1), 230. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010230