Cause-Related Marketing in the Telecom Sector: Understanding the Dynamics among Environmental Values, Cause-Brand Fit, and Product Type

Abstract

1. Introduction

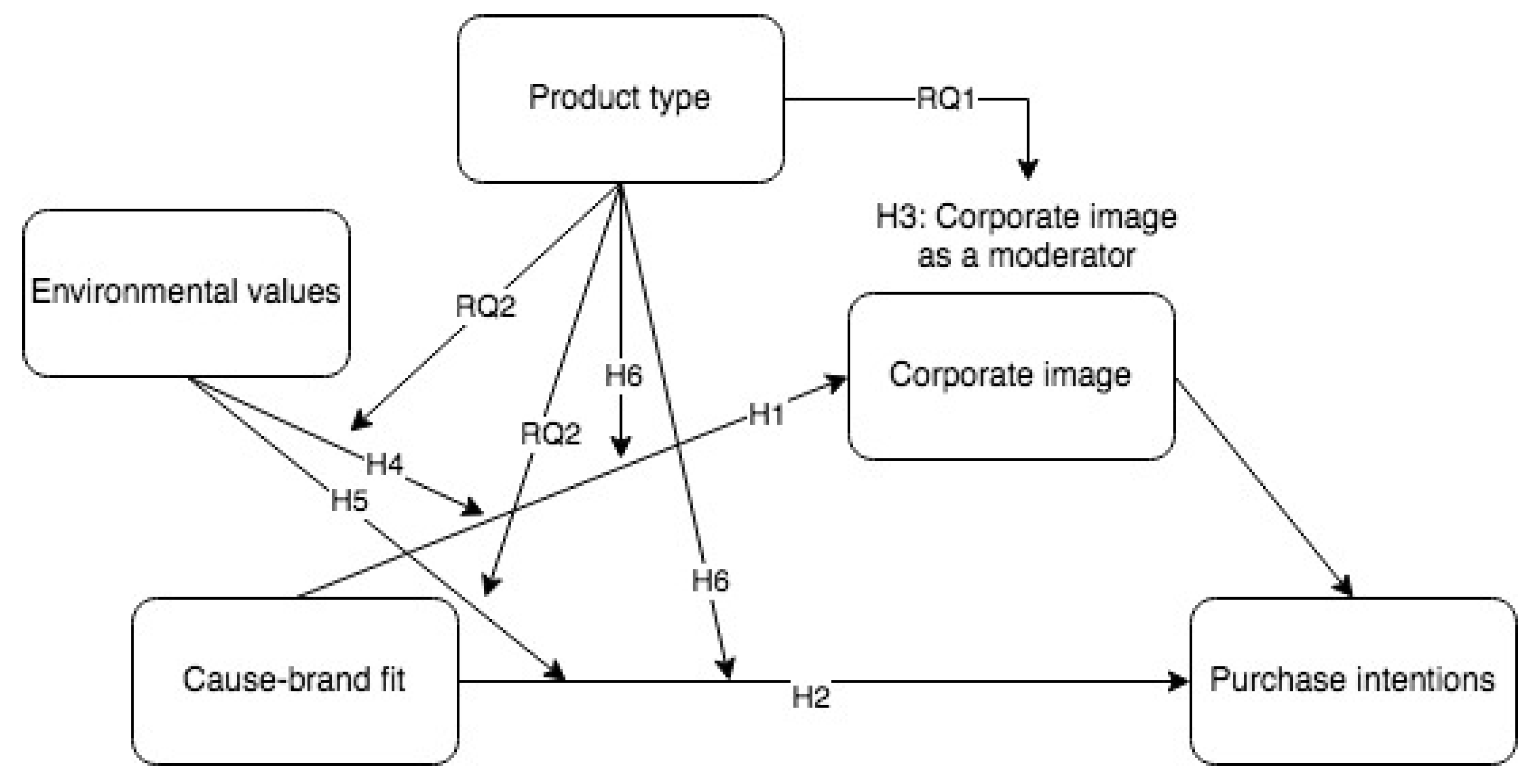

2. Theoretical Framework, Hypotheses, and Research Questions

2.1. Cause-Related Marketing

2.2. The Effect of Cause-Brand Fit on Corporate Image and Purchase Intentions

2.3. Overall Relationship Among CRM, Corporate Image, and Purchase Intention

2.4. The Role of Environmental Values

2.5. The Moderating Role of Product Type

3. Methods

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Stimulus Materials and Pretest

3.3. Participants and Procedure of the Experiment

3.4. Dependent Variable

3.5. Mediating and Moderating Variables

4. Results

4.1. Manipulation Check

4.2. Hypotheses Testing and Research Questions

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Buhmann, K.; Jonsson, J.; Fisker, M. Do no harm and do more good too: Connecting the SDGs with business and human rights and political CSR theory. Corp. Gov. 2019, 19, 309–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhmann, K. Future perspectives: Doing good but avoiding SDG-washing. Creating relevant societal value without causing harm. In OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises: A Glass Half Full; Mulder, H., Voort, S.V., Eds.; OECD: Paris, France; Nyenrode Business University: Nyenrode, Poland, 2018; pp. 127–134. [Google Scholar]

- Grimmer, M.; Woolley, M. Green marketing messages and consumers’ purchase intentions: Promoting personal versus environmental benefits. J. Mark. Commun. 2014, 20, 231–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-H.; Shin, D. Consumers’ responses to CSR activities: The linkage between increased awareness and purchase intention. Public Relat. Rev. 2010, 36, 193–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimmer, M.; Bingham, T. Company environmental performance and consumer purchase intentions. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1945–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C.R. A call for more research on ‘green’ or environmental advertising. Int. J. Advert. 2015, 34, 573–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafferty, B.A. The relevance of fit in a cause–brand alliance when consumers evaluate corporate credibility. J. Bus. Res. 2007, 60, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chéron, E.; Kohlbacher, F.; Kusuma, K. The effects of brand cause fit and campaign duration on consumer perception of cause-related marketing in Japan. J. Consum. Mark. 2012, 29, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melero, I.; Montaner, T. Cause-related marketing: An experimental study about how the product type and the perceived fit may influence the consumer response. Eur. J. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2016, 25, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, X.; Heo, K. Consumer responses to corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives: Examining the role of brand-cause fit in cause-related marketing. J. Advert. 2007, 36, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T. The value basis of environmental concern. J. Soc. Issues 1994, 50, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P. Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strahilevitz, M.; Myers, J.G. Donations to charity as purchase incentives: How well they work may depend on what you are trying to sell. J. Consum. Res. 1998, 24, 434–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghingold, M. Guilt arousing communications: An unexplored variable. In Advances in Consumer Research; Monroe, K., Ed.; Association of Consumer Research: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1981; Volume 8, pp. 442–448. [Google Scholar]

- Lerro, M.; Raimondo, M.; Stanco, M.; Nazzaro, C.; Marotta, G. Cause Related Marketing among Millennial Consumers: The Role of Trust and Loyalty in the Food Industry. Sustainability 2019, 11, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadarajan, P.R.; Menon, A. Cause-related marketing: A coalignment of marketing strategy and corporate philanthropy. J. Mark. Manag. 1988, 52, 58–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brønn, P.; Vrioni, A. Corporate social responsibility and cause-related marketing: An overview. Int. J. Advert. 2001, 20, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreasen, A.R. Profits for nonprofits: Find a corporate partner. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1996, 74, 47–50. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.J.; Dacin, P.A. The company and the product: Corporate associations and consumer product responses. J. Mark. 1997, 61, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Lai, K.K. The effect of corporate social responsibility on brand loyalty: The mediating role of brand image. Total. Qual. Manag. Bus. Excel. 2014, 25, 249–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Riel, C.B.; Fombrun, C.J. Essentials of Corporate Communication: Implementing Practices for Effective Reputation Management; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2007; p. 40. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C.-P. The relationships among corporate social responsibility, corporate image and economic performance of high-tech industries in Taiwan. Qual Quant. 2009, 43, 417–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, P.; del Bosque, I.R. Explaining Consumer Behavior in the Hospitality Industry: CSR Associations and Corporate Image. In Handbook of Research on Global Hospitality and Tourism Management; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2015; pp. 501–519. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.-Y. Does corporate social responsibility influence customer loyalty in the Taiwan insurance sector? The role of corporate image and customer satisfaction. J. Promot. Manag. 2019, 25, 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, D.; Monroe, K.B.; Krishnan, R. The effects of price-comparison advertising on buyers’ perceptions of acquisition value, transaction value, and behavioral intentions. J. Mark. 1998, 62, 46–59. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, J.D.; Gadhavi, D.D.; Shukla, Y.S. Consumers’ responses to cause related marketing: Moderating influence of cause involvement and skepticism on attitude and purchase intention. Int. Rev. Public Nonprofit Mark. 2017, 14, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Does doing good always lead to doing better? Consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility. J. Mark. Res. 2001, 38, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.; Cameron, G.T. Conditioning effect of prior reputation on perception of corporate giving. Public Relat. Rev. 2006, 32, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker-Olsen, K.L.; Cudmore, B.A.; Hill, R.P. The impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, S.; Kahn, B.E. Corporate sponsorships of philanthropic activities: When do they impact perception of sponsor brand? J. Consum. Psychol. 2003, 13, 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigné-Alcañiz, E.; Currás-Pérez, R.; Ruiz-Mafé, C.; Sanz-Blas, S. Cause-related marketing influence on consumer responses: The moderating effect of cause–brand fit. J. Mark. Commun. 2012, 18, 265–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, N.; Guha, A.; Biswas, A.; Krishnan, B. How product–cause fit and donation quantifier interact in cause-related marketing (CRM) settings: Evidence of the cue congruency effect. Mark. Lett. 2016, 27, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Mandler, G. The Structure of Value: Accounting for Taste. In Affect and Cognition: The 17th Annual Carnegie Symposium on Cognition; Margaret, H., Clarke, S., Fiske, S.T., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1982; pp. 3–36. [Google Scholar]

- Jurca, M.A.; Madlberger, M. Ambient advertising characteristics and schema incongruity as drivers of advertising effectiveness. J. Mark. Commun. 2015, 21, 48–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjödin, H.; Törn, F. When communication challenges brand associations: A framework for understanding consumer responses to brand image incongruity. J. Consum. Behav. 2006, 5, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmon-Kizer, T.R. The effects of schema congruity on consumer response to celebrity advertising. J. Mark. Commun. 2017, 23, 162–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pracejus, J.W.; Olsen, G.D. The role of brand/cause fit in the effectiveness of cause-related marketing campaigns. J. Bus. Res. 2004, 57, 635–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosmayer, D.C.; Fuljahn, A. Corporate motive and fit in cause related marketing. J. Prod. Brand. Manag. 2013, 22, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafferty, B.A. Selecting the right cause partners for the right reasons: The role of importance and fit in cause-brand alliances. Psychol. Mark. 2009, 26, 359–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.; Gürhan-Canli, Z.; Schwarz, N. The effect of corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities on companies with bad reputations. J. Consum. Psychol. 2006, 16, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zasuwa, G. The role of company-cause fit and company involvement in consumer responses to CSR initiatives: A meta-analytic review. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, E.R.; Balmer, J.M. Managing corporate image and corporate reputation. Long Range Plann. 1998, 31, 695–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demetriou, M.; Papasolomou, I.; Vrontis, D. Cause-related marketing: Building the corporate image while supporting worthwhile causes. J. Brand. Manag. 2010, 17, 266–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhamme, J.; Lindgreen, A.; Reast, J.; Van Popering, N. To do well by doing good: Improving corporate image through cause-related marketing. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 109, 259–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornwell, T.B.; Coote, L.V. Corporate sponsorship of a cause: The role of identification in purchase intent. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Kumar Dokania, A.; Swaroop Pathak, G. The influence of green marketing functions in building corporate image: Evidences from hospitality industry in a developing nation. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 2178–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. Consumer responses to the food industry’s proactive and passive environmental CSR, factoring in price as CSR tradeoff. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grau, S.L.; Folse, J.A.G. Cause-related marketing (CRM): The influence of donation proximity and message-framing cues on the less-involved consumer. J. Advert. 2007, 36, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broderick, A.; Jogi, A.; Garry, T. Tickled pink: The personal meaning of cause related marketing for customers. J. Mark. Manag. 2003, 19, 583–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohlmann, C.; Krumbholz, L.; Zacher, H. The triple bottom line and organizational attractiveness ratings: The role of proenvironmental attitude. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 912–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.T.; Liu, H.W. Goodwill hunting? Influences of product-cause fit, product type, and donation level in cause-related marketing. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2012, 30, 634–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernev, A. The goal-attribute compatibility in consumer choice. J. Consum. Psychol. 2004, 14, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, U.; Dhar, R.; Wertenbroch, K. A behavioral decision theory perspective on hedonic and utilitarian choice. In Inside Consumption: Frontiers of Research on Consumer Motives, Goals, and Desires; Ratneshwar, S., Glen Mick, D., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2005; Volume 1, pp. 144–165. [Google Scholar]

- Melnyk, V.; Klein, K.; Völckner, F. The double-edged sword of foreign brand names for companies from emerging countries. J. Mark. 2012, 76, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghi, I.; Antonetti, P. High-fit charitable initiatives increase hedonic consumption through guilt reduction. Eur. J. Mark. 2017, 51, 2030–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, R.W. Possessions and the extended self. J. Consum. Res. 1988, 15, 139–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Duque, L.C. Familiarity and format: Cause-related marketing promotions in international markets. Int. Mark. Rev. 2019, 5, 901–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortin, D.; Uncles, M.; Carlson, J.; O’Cass, A. Managing web site performance taking account of the contingency role of branding in multi-channel retailing. J. Consum. Mark. 2011, 28, 524–531. [Google Scholar]

- Speed, R.; Thompson, P. Determinants of sports sponsorship response. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2000, 28, 226–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insightxplore. iPhone Users Increased by 5%; Smart TV Box/ Stick Use Reached 10%. Available online: https://www.ixresearch.com/news/news_02_21_19 (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- TWNIC. 2020 Taiwan Internet Report. Available online: https://report.twnic.tw/2020/en/index.html (accessed on 10 January 2021).

- Riordan, C.M.; Gatewood, R.D.; Bill, J.B. Corporate image: Employee reactions and implications for managing corporate social performance. J. Bus. Ethics 1997, 16, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.E. The new environmental paradigm scale: From marginality to worldwide use. J. Environ. Educ. 2008, 40, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, L.C.R.; Chaminda, J.W.D. Corporate social responsibility and product evaluation: The moderating role of brand familiarity. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2013, 20, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türkel, S.; Uzunoğlu, E.; Kaplan, M.D.; Vural, B.A. A strategic approach to CSR communication: Examining the impact of brand familiarity on consumer responses. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2016, 23, 228–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godey, B.; Manthiou, A.; Pederzoli, D.; Rokka, J.; Aiello, G.; Donvito, R.; Singh, R. Social media marketing efforts of luxury brands: Influence on brand equity and consumer behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 5833–5841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; Hung, C.; Frumkin, P. An experimental test of the impact of corporate social responsibility on consumers’ purchasing behavior: The mediation role of trust. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 2972–2982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strahilevitz, M. The effects of product type and donation magnitude on willingness to pay more for a charity-linked brand. J. Consum. Psychol. 1999, 8, 215–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitt, T. Marketing intangible products and product intangibles. Cornell Hotel Restaur. Adm. Q. 1981, 22, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Rodríguez-Serrano, M.Á.; Lambkin, M. Corporate social responsibility and marketing performance: The moderating role of advertising intensity. J. Advert. Res. 2017, 57, 368–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.; Oh, S. Introduction to the special issue on social and environmental issues in advertising. Int. J. Advert. 2016, 35, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

| Corporate Image | Purchase Intentions | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| df | F | P | η2 | Df | F | p | η2 | |

| Cause-brand fit | 3 | 5.49 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 3 | 3.61 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Product type | 1 | 2.52 | 0.18 | 0.02 | 1 | 2.19 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| Fit × type | 3 | 0.42 | 0.74 | 0.00 | 3 | 1.39 | 0.25 | 0.00 |

| Error | 1167 | 1167 | ||||||

| Total | 1175 | 1175 | ||||||

| DV = Corporate Image | DV = Purchase Intention | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unstandardized coefficient | p | Unstandardized coefficient | p | |

| WFP | 0.25 (0.08) | 0.00 | 0.08 (0.12) | 0.48 |

| GWF | 0.31 (0.08) | 0.00 | 0.16 (0.12) | 0.19 |

| IEMFA | 0.21 (0.08) | 0.01 | −0.06 (0.12) | 0.63 |

| Product type (hedonic product = 1) | −0.09 (0.05) | 0.10 | −0.35 (0.08) | 0.00 |

| Corporate image | 0.70 (0.04) | 0.00 | ||

| Conditions | Index | BootSE | BootLLCI | BootULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WFP vs. control | 0.16 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.32 |

| GWF vs. control | 0.21 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.38 |

| IEMFA vs. control | 0.20 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.38 |

| Conditions | Effect | BootSE | BootLLCI | BootULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hedonic product (i.e., iPhone) | ||||

| WFP | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.26 |

| GWF | 0.17 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.33 |

| IEMFA | 0.07 | 0.07 | −0.05 | 0.21 |

| Utilitarian product (i.e., 4G service) | ||||

| WFP | 0.22 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.43 |

| GWF | 0.26 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.47 |

| IEMFA | 0.23 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.44 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shih, T.; Wang, S.S. Cause-Related Marketing in the Telecom Sector: Understanding the Dynamics among Environmental Values, Cause-Brand Fit, and Product Type. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5129. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13095129

Shih T, Wang SS. Cause-Related Marketing in the Telecom Sector: Understanding the Dynamics among Environmental Values, Cause-Brand Fit, and Product Type. Sustainability. 2021; 13(9):5129. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13095129

Chicago/Turabian StyleShih, Tsungjen, and Shaojung Sharon Wang. 2021. "Cause-Related Marketing in the Telecom Sector: Understanding the Dynamics among Environmental Values, Cause-Brand Fit, and Product Type" Sustainability 13, no. 9: 5129. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13095129

APA StyleShih, T., & Wang, S. S. (2021). Cause-Related Marketing in the Telecom Sector: Understanding the Dynamics among Environmental Values, Cause-Brand Fit, and Product Type. Sustainability, 13(9), 5129. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13095129