Household Food Waste from an International Perspective

Author Contributions

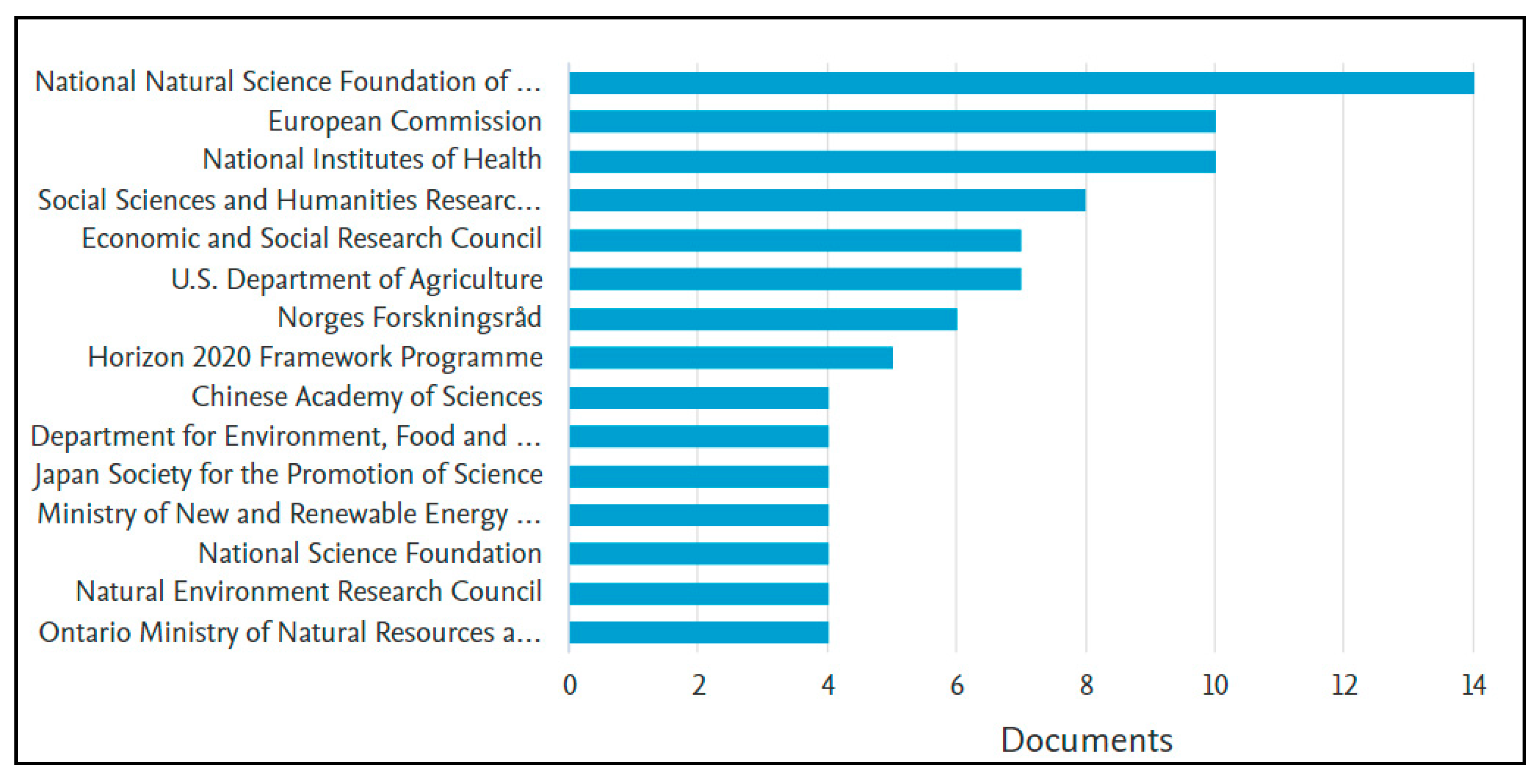

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gustavsson, J.; Cederberg, C.; Sonesson, U.; van Otterdijk, R.; Meybeck, A. Global Food Losses and Food Waste: Extent, Causes and Prevention; Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Forbes, H.; Quested, T.; O’Connor, C. Food Waste Index Report 2021; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- European Commision. EC Delegated Decision, C. 3211 Final and Annex. Supplementing Directive 2008/98/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council as Regards a Common Methodology and Minimum Quality Requirements for the Uniform Measurement of Levels of Food Waste. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/transparency/regdoc/rep/3/2019/EN/C-2019–3211-F1-EN-MAIN-PART-1.PDF (accessed on 3 March 2021).

- Giordano, C.; Falasconi, L.; Cicatiello, C.; Pancino, B. The role of food waste hierarchy in addressing policy and research: A comparative analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 252, 119617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, C.; Piras, S.; Boschini, M.; Falasconi, L. Are questionnaires a reliable method to measure food waste? A pilot study on Italian households. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 2885–2897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, C.; Alboni, F.; Falasconi, L. Quantities, determinants and awareness of households’ food waste in Italy: A com-parison between diary and questionnaires quantities. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elimelech, E.; Ert, E.; Ayalon, O. Exploring the Drivers behind Self-Reported and Measured Food Wastage. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Werf, P.; Seabrook, J.A.; Gilliland, J.A. Food for thought: Comparing self-reported versus curbside measurements of household food wasting behavior and the predictive capacity of behavioral determinants. Waste Manag. 2020, 101, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Herpen, E.; van Geffen, L.; Vries, M.N.-D.; Holthuysen, N.; van der Lans, I.; Quested, T. A validated survey to measure household food waste. MethodsX 2019, 6, 2767–2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebersorger, S.; Schneider, F. Discussion on the methodology for determining food waste in household waste composition studies. Waste Manag. 2011, 31, 1924–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicatiello, C. Measuring household food waste at national level: A systematic review on methods and results. CAB Rev. Perspect. Agric. Veter. Sci. Nutr. Nat. Resour. 2018, 13, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham-Rowe, E.; Jessop, D.C.; Sparks, P. Identifying motivations and barriers to minimising household food waste. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2014, 84, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham-Rowe, E.; Jessop, D.C.; Sparks, P. Predicting household food waste reduction using an extended theory of planned behaviour. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2015, 101, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stancu, V.; Haugaard, P.; Lähteenmäki, L. Determinants of consumer food waste behaviour: Two routes to food waste. Appetite 2016, 96, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Werf, P.; Seabrook, J.A.; Gilliland, J.A. Reduce food waste, save money: Testing a novel intervention to reduce household food waste. Environ. Behav. 2021, 53, 151–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, C.; Goucher, L.; Quested, T.; Bromley, S.; Gillick, S.; Wells, V.K.; Evans, D.; Koh, L.; Kanyama, A.C.; Katzeff, C.; et al. Review: Consumption-stage food waste reduction interventions—What works and how to design better interventions. Food Policy 2019, 83, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soma, T.; Li, B.; Maclaren, V. Food waste reduction: A test of three consumer awareness interventions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quested, T.; Marsh, E.; Stunell, D.; Parry, A. Spaghetti soup: The complex world of food waste behaviours. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2013, 79, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visschers, V.H.M.; Wickli, N.; Siegrist, M. Sorting out food waste behaviour: A survey on the motivators and barriers of self-reported amounts of food waste in households. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 45, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schanes, K.; Dobernig, K.; Gözet, B. Food waste matters—A systematic review of household food waste practices and their policy implications. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 182, 978–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Geffen, L.; Van Herpen, E.; Van Trijp, H. Household food waste—How to avoid it? an integrative review. Food Waste Management 2019, 27–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soma, T. The tale of the crying rice: The role of unpaid foodwork and learning in food waste prevention and reduction in Indonesian households. In Learning, Food and Sustainability: Sites for Resistance and Change; Sumner, J., Ed.; Pal-grave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA; pp. 19–34.

- Soma, T. Gifting, ridding and the “everyday mundane”: The role of class and privilege in food waste generation in Indonesia. Local Environ. 2017, 22, 1444–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popkin, B.M. The nutrition transition and obesity in the developing world. J. Nutr. 2001, 131, 871S–873S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herzberg, R.; Schmidt, T.G.; Schneider, F. Characteristics and determinants of domestic food waste: A representative diary study across Germany. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Werf, P.; Larsen, K.; Seabrook, J.; Gilliland, J. How neighbourhood food environments and a pay-as-you-throw (payt) waste program impact household food waste disposal in the city of Toronto. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, M.H.; Ghazi, T.; Hamzah, M.; Manaf, L.; Tahir, R.; Nasir, A.M.; Omar, A.E. Impact of movement control order (MCO) due to coronavirus disease (COVID-19) on food waste generation: A case study in Klang Valley, Malaysia. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelau, C.; Sarbu, R.; Serban, D. Cultural influences on fruit and vegetable food-wasting behavior in the European Union. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations Across Nations; Sage Publication: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Pocol, C.; Pinoteau, M.; Amuza, A.; Burlea-Schiopoiu, A.; Glogovețan, A.-I. Food waste behavior among romanian consumers: A cluster analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falasconi, L.; Cicatello, C.; Franco, S.; Segre, A.; Setti, M.; Vttuari, M.; Cusano, I. Consumer approach to food waste: Evidences from a large scale survey in Italy. Italian Rev. Agric. Econ. 2016, 71, 266–278. [Google Scholar]

- Gaiani, S.; Caldeira, S.; Adorno, V.; Segrè, A.; Vittuari, M. Food wasters: Profiling consumers’ attitude to waste food in Italy. Waste Manag. 2018, 72, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Talia, E.; Simeone, M.; Scarpato, D. Consumer behaviour types in household food waste. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 214, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, K.; Javadi, F.; Hiramatsu, M. Influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on household food waste behavior in Japan. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal-Mones, B.; Barco, H.; Diaz-Ruiz, R.; Fernandez-Zamudio, M.-A. Citizens’ food habit behavior and food waste consequences during the first COVID-19 lockdown in Spain. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, V.; Cequea, M.; Neyra, J.V.; Ferasso, M. Consumption behavior and residential food waste during the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak in Brazil. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Hassen, T.; El Bilali, H.; Allahyari, M.S. Impact of COVID-19 on food behavior and consumption in Qatar. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jribi, S.; Ben Ismail, H.; Doggui, D.; Debbabi, H. COVID-19 virus outbreak lockdown: What impacts on household food wastage? Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 22, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Principato, L.; Secondi, L.; Cicatiello, C.; Mattia, G. Caring more about food: The unexpected positive effect of the Covid-19 lockdown on household food management and waste. Socioecon. Plan Sci. 2020, 100953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przezbórska-Skobiej, L.; Wiza, P. Food waste in households in Poland—Attitudes of young and older consumers towards the phenomenon of food waste as demonstrated by students and lecturers of PULS. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keegan, E.; Breadsell, J. Food waste and social practices in Australian households. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, C.; Piras, S.; Graziano, R.P.; Lazzarini, M.; Spaghi, S. Alternative food networks and household food waste: Evidence from an Italian case study. In Proceedings of the RETASTE Conference, Session: Food Loss and Waste Prevention, Athens, Greece, 6–8 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, D. Blaming the consumer—Once again: The social and material contexts of everyday food waste practices in some English households. Crit. Public Heal. 2011, 21, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messner, R.; Richards, C.; Johnson, H. The “Prevention Paradox”: Food waste prevention and the quandary of systemic surplus production. Agric. Hum. Values 2020, 37, 805–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berti, G.; Giordano, C.; Mininni, M. Assessing the transformative potential of food banks: The case study of magazzini sociali (Italy). Agriculture 2021, 11, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNCTAD Handbook of Statistics 2020 Population. Available online: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/tdstat45_FS11_en.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2021).

- Köster, E. Diversity in the determinants of food choice: A psychological perspective. Food Qual. Preference 2009, 20, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gram, M. Self-reporting vs. observation: Some cautionary examples from parent/child food shopping behaviour. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2010, 34, 394–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, L.G.; Keller, P.A.; Vallen, B.; Williamson, S.; Birau, M.M.; Grinstein, A.; Haws, K.L.; LaBarge, M.C.; Lamberton, C.; Moore, E.S.; et al. The squander sequence: Understanding food waste at each stage of the consumer decision-making process. J. Public Policy Mark. 2016, 35, 292–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | Objective | Methodology | Country |

|---|---|---|---|

| Van der Werf et al. 2020 | Assessing household food waste quantities and determinants | Waste compositional analysis on a large-scale sample | Canada |

| Herzberg et al. 2020 | Assessing household food waste and determinants | Food diaries on a large-scale sample | Germany |

| Heikal et al. 2020 | Assessing household food waste during the first COVID-19 lockdown | Application of proxy over a waste compositional analysis | Malaysia |

| Pelau et al. 2020 | Establishing relation between cultural influence (Hofstede’s cultural dimensions) and fruits/veg waste | Hofstede’s cultural dimensions analysis | European Union |

| Pocol et al. 2020 | Identifying types of consumers depending on their perception of food waste | On-line questionnaire | Romania |

| Qian et al. 2020 | Assessing household food waste during the first COVID-19 lockdown | On-line questionnaire | Japan |

| Przezbórska-Skobiej et al. 2021 | Attitudes of young and older consumers towards the phenomenon of food waste | On-line questionnaire | Poland |

| Vidal-Mones et al. 2021 | Food habits and food waste during the first lockdown due to COVID-19 | On-line questionnaire | Spain |

| Schmitt et al. 2021 | Food consumption and wastage behavior in Brazil during the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak | On-line questionnaire | Brazil |

| Keegan and Breadsell 2021 | Household food waste quantities and motivations | Social practice theory approach and food waste diary | Australia |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Giordano, C.; Franco, S. Household Food Waste from an International Perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5122. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13095122

Giordano C, Franco S. Household Food Waste from an International Perspective. Sustainability. 2021; 13(9):5122. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13095122

Chicago/Turabian StyleGiordano, Claudia, and Silvio Franco. 2021. "Household Food Waste from an International Perspective" Sustainability 13, no. 9: 5122. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13095122

APA StyleGiordano, C., & Franco, S. (2021). Household Food Waste from an International Perspective. Sustainability, 13(9), 5122. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13095122