1. Introduction

Little is known about the contribution of bills (laws-under-consideration) to the promotion of housing rights. Less is known on whether the content of housing-related-bills reflects the State’s ruling political and economic regime, and what type of housing related rights are being enacted under a certain political-economic regime (provisions or protections). Will changes in the political-economic regime be reflected in the contents or volume of housing-related bills? And what type of bill is most likely to be enacted: a provision or a protection? The answers of these questions are the challenges of this study.

While some bills will evolve from an idea to a published statute, a relatively large number will never pass the first vote, leaving a variety of economic, social and political concerns unattended.

The relevance of the above questions is heightened by the escalating global housing- crisis, amid the global financial meltdown of 2007–2008 [

1,

2]. The crisis most commonly manifested in a shortage of affordable housing for moderate- and low-income households [

3,

4,

5]. Consequently, governments worldwide stepped in to increase the supply of affordable housing, through various legislative and policy tools to promote the right to housing. Spain, for example, enacted laws to increase the protection of mortgage consumers [

6]; and the United States Congress passed the Housing and Economic Recovery Act of 2008 [

7]. Thus, it is now more important than ever to explore the various instruments available in countries around the globe to promote housing rights.

This paper examines a previously denoted relation between bills and changes in the dominant political-economic conditions [

8] looking at the case of Israel. Israel is interesting for three main reasons. First, during the country’s 71-year existence it has undergone changes in its dominant political-economic regime, reflecting a global policy change from a social-democratic state to a neoliberal one [

9,

10,

11]. Second, the country’s population growth of 1.9% (2018), higher than the OECD average (0.7%), and large immigration waves makes housing generation a pressing concern, thus we would expect diligent legislative activity. Third, unlike most OECD countries, where housing prices fell sharply following the 2007–2008 financial crisis and began to recover only in 2012 [

12], Israel experienced a sharp rise in housing prices: Between 2007 and 2015 the cost of both new and second-hand housing rose by 70% [

13]. This rise contributed to the eruption of Israel’s largest-ever social protest, in the summer of 2011, over the high cost of living [

14,

15,

16,

17]. We would also expect to see the repercussion of such events in the proposed bills.

Our theoretical framework is based on the classic distinction between legal provisions (positive rights) and legal protection (negative rights) from the realm of human rights. Where according to literature social democracies or welfare states are associated with provisions (such as health care, education, and adequate housing) while neoliberal regimes are associated with protections that minimize state intervention in the individual’s life (as well as in the housing market) [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23].

The theoretical framework is followed by an empirical cumulative-aggregative analysis, which examines (quantitatively and qualitatively) the scope and content of housing-related bills in the Knesset (the Israeli parliament) since its establishment in 1948. In this sense, this research is innovative, creating a unique housing-related bills library, and the first to analyze these bills.

The research findings are counterintuitive. During the first decades, Israel, often described as a welfare state, enacted mostly protections, whereas in later decades, under a dominant neoliberal regime, several bills proposed housing provisions. The volume of bills and the thematic range increased significantly over the years.

These findings bridge the often-separated fields of housing studies and housing policy (and law). With the global housing affordability crisis, they also offer a new and unexplored methodology to learn about housing legislation practices, that could be potentially replicated to other countries, and could be useful to international bodies (UN-Habitat, for example) that are currently looking alter the legal and institutional housing rights landscapes and to promote housing rights.

This paper has five sections. The next section introduces the main literature on housing rights and the political-economic nexus. The third section describes the methodology. The fourth and fifth sections present the analysis, and the sixth discusses the findings.

2. Housing Rights and Housing Legislation

Various instruments have been employed to promote housing rights including different fiscal and policy tools [

24,

25,

26]. Nevertheless, most countries have failed to adopt the full extent necessary to ensure the widespread enjoyment of housing rights [

26,

27]. One of the key instruments is legislation, and some scholars consider it to be the most important tool [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32].

This section, briefly reviews the development of housing law overtime by thematic strands, we later use these strands for our own thematic classification of housing related bills. However, before we dive into the thematic strands, it should be noted that this is not a legal analysis study. We do not analyze laws, only bills. Unlike laws, the intentions of which, may be open to interpretation, bills are laws-under-consideration or drafts of laws that come with a long explanatory note intended to convince other parliament members that the proposed law is important and makes sense. Bills are an important indicator of a variety of economic, social and political concerns brought before Parliament. Unapproved bills may not be able to get a majority because of narrow coalition considerations, regardless of their potential contribution to society.

The history of housing within the modern law curriculum is relatively short. According to Partington (1983) [

33] there was no body of legislation called housing law. Housing legislation was drawn from many areas of legislation (e.g., criminal, civil, and international) [

34]. At the beginning of the 20th century, post-World War I it evolved as “public housing law”.

In the last decades, scholars [

33] started outlining the different types of legal relationships in housing and mapping its chronological evolution in several strands according to the type and theme of the legislation enacted [

34]. They often involved the provision of various housing rights.

The first strand of housing law included poor laws that evolved into modern social rights, social welfare law, and homelessness legislation. Poor laws included themes such as eligibility, deserving individuals, and importance of locality [

35].

The second strand was sanitation or public health; it was also the first legislative intervention in the relationship between landlord and tenant concerning the state of rented properties. Unlike the poor law, diseases like cholera affected all classes. The principal concerns were overcrowding and common lodging houses that were regarded as unhygienic. Powers were given to close or demolish individual housing units that were unfit for human habitation and to clear areas of unsanitary housing [

36].

A third strand were security concerns, which were pressing during World War I. Rent control and security of tenure were made available because of wartime conditions. Rent control fitted into the complex of direct controls over prices, materials, and manpower. Because new housing construction was on hold and increasing demand could not be met, housing shortages led to rent increases, and nonpayers were evicted [

37].

The fourth strand was tenure, which belongs to property law. In terms of housing law, tenure relates to a range of rights and obligations held by the occupier and by housing providers [

34].

A strand that is particular to Israel is land use, established by the Planning and Construction Law, which regulates, restricts, or permits certain features of housing [

38]. These strands expose the variety of legal areas where housing may be promoted [

31].

Housing Provisions and Protections

The contemporary debate over rights including housing had its roots in the post-World War II period, with the 1948 UN Declaration of Human Rights (UNDHR) [

39].

Although the UN asserted in multiple documents that human rights are, inter alia, universal and inalienable, interdependent and indivisible, scholars offered various classifications of human rights. One common classification distinguished positive from negative rights, based on Isaiah Berlin’s seminal work “Two concepts of liberty” (1969) [

40].

Positive rights entitle the holder to the provision of some good or service that mandates action and others must act with respect to the right holder. Rights considered positive, as initially proposed by Vašák (1979) [

41], were mostly economic, social and cultural rights such as housing, food, education, employment.

Negative rights entitle the holder to a certain freedom or protection from harm if he or she tries to get something for himself or herself (inaction) [

18,

21,

22] and forbids others from acting against the right holder. Rights considered negative include civil and political rights such as freedom of speech, life, private property.

In theory, housing was often classified positive, a good to be provided by the State. However, today we know housing rights can appear in both positive (provisions) or negative (protections) forms. Following Vasaks’s proposition, Oren (2017) [

32] found in a survey of the world’s constitutions that a minority of housing rights clauses contained negative rights (19%). Although a majority of 81% (clauses in 64 national constitutions with direct and embedded housing rights) still committed to positively provide, or strive to provide, housing or the means and measures to obtain housing.

The positive-negative rights classification points out at the state’s role, the budgetary allocation of resources, and the political-economic regimes. Marks [

22] (2009: 221–237) suggested positive-rights require large expenditure and therefore corresponded to social democracies or welfare states committed to adequate housing, health care provision, education and to its residents. While negative rights require the state to act solely as a regulator, an invest much less money, corresponding to liberal or neoliberal political-economic regimes based on minimal state intervention in the individual’s life and in the economic market as well as in the housing market [

19,

20,

22,

23].

This approach had been countered as some argue that housing rights are not purely limited to one regime or another [

27,

31,

39,

42,

43]. Nevertheless, we found that Mark’s [

22] theoretical distinction reflects well the state’s willingness to invest (or not) in the provision of various public services, on top of them, housing, and we connect between the type of right and the type of regime it represents to analyse the “housing rights” proposed in the evaluated bills.

3. Research Methodology

The methodology combines quantitative and qualitative methods to empirically analyze the full set of housing-related bills proposed by the Israeli Parliament (the Knesset) since its inception (1948 to June 2019).

First, we created a housing-related bills (“hatzaot hok” in Hebrew) library. To identify these bills, we selected 10 Hebrew keywords, including various inflections of the following terms: housing, home, rental, and mortgage. Then we used JavaScript code to extract the relevant bills from the Knesset’s open legislation database through a scraping process. Our first search retrieved 3099 bills that were sorted and cleaned. The word “house” appeared in unrelated contexts, for example, beit din (“house of judgment,” the Hebrew term for “court”). We reduced the number of bills to 932 following three rounds of sorting: one programmed and two manual.

At the second stage we carried out the data analysis, both quantitative and qualitative. The bills in our library were classified into five dimensions:

(1) Time—Sorted into seven decades, starting from the 1950s. This enabled us to compare quantitatively the number of bills submitted each decade in each category.

(2) The bill’s status—enacted or not enacted. Because of the large number of bills and the variety of issues they deal with, we could not address the various legislative phases of each bill.

(3) The bill’s initiator—If introduced by the government, a “governmental bill” or by one or several MKs (members of the ‘Knesset’), “private bill” (In exceptional cases, the initiator of the bill could be a Knesset committee). Governmental bills require a greater consensus and have a better chance of being enacted but are harder to achieve.

(4)

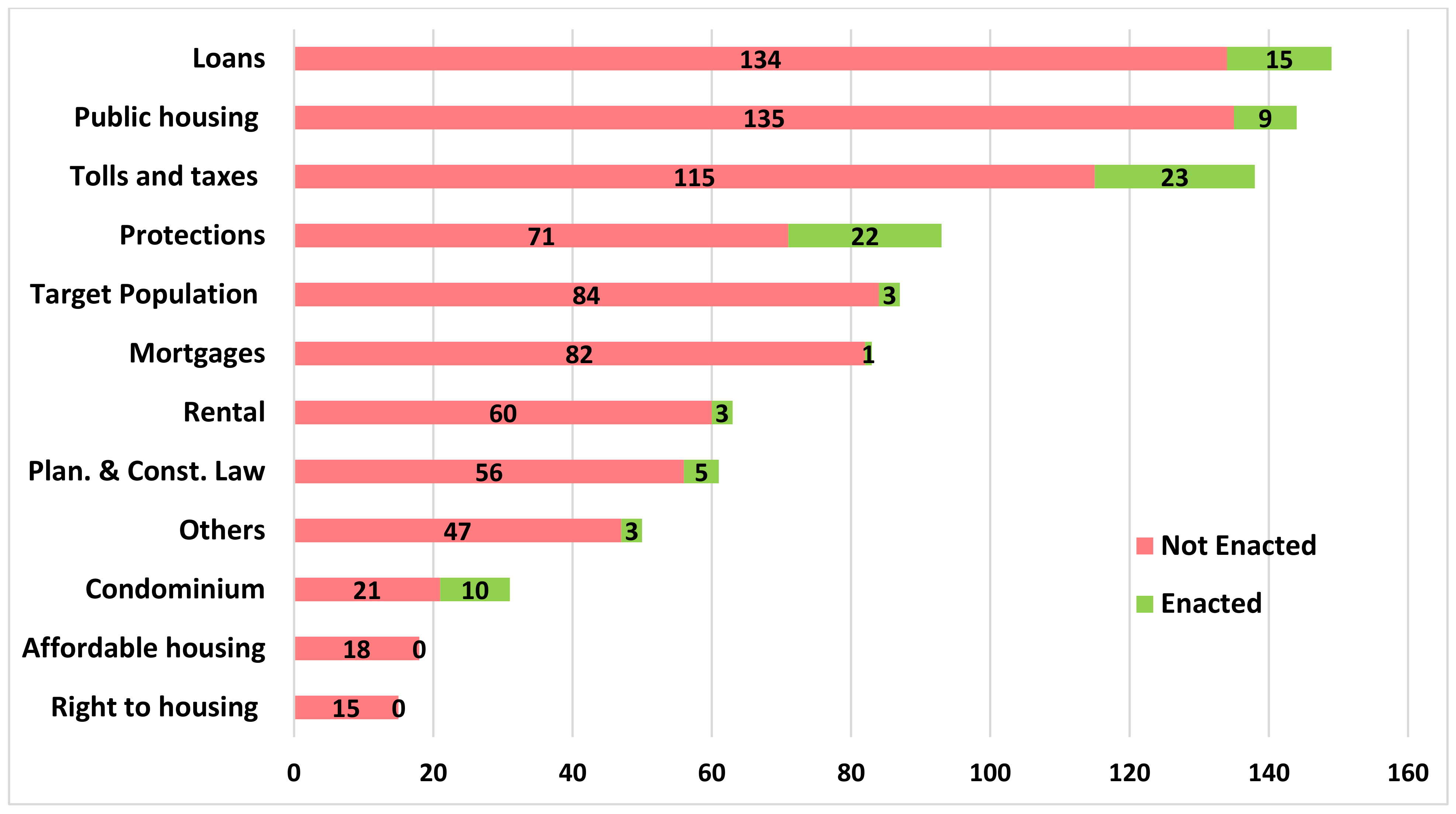

Theme—12 sub-categories from the library findings based on the strands mentioned in the second section are presented in

Figure 1.

To assure the exclusiveness of the thematic classification (for example, a bill on discounted rents for new immigrants, could classify either as target populations or rental) we used the explanatory notes as a clarification.

Appendix A lists the various themes included under each category.

(5) Type of rights—We classified each bill either as promoting positive or negative right (provisions vs. protections), as mentioned in the second section. Negative rights included bills proposing various procedural aspects, such as conditions for mortgage eligibility or tax relief; the authority and threshold conditions for joint-home decisions; regulation of condominium budget management; and the licencing conditions to operate sheltered housing. This classification was particularly challenging, requiring in-depth examination of each bill. An exception was the protection topic (for example, tenant protection), which included negative rights.

Methodological Obstacles and Challenges

At the database level, the scraped bills were withdrawn from a governmental website, forcing us to rely on published material. Therefore, any unpublished material may have been automatically excluded from the library. Since, housing is not considered a sensitive area of information, one may assume that the entire set of bills were published. Using JavaScript code to sort relevant bills may save time, but it is highly dependent on the selection of keywords. We took in consideration the possibility that some bills may have been missed or omitted. We did not rely solely on the programmed sorting; we also scanned the bills manually, to “clean” the data, omit irrelevant bills, or add important missing bills.

A second challenge we encountered concerned the classification between positive and negative rights. In cases where the classification was ambivalent (25 cases, 2.6% only), in a similar way to the thematic classification, we read the bill and retrieved our decision using the explanatory notes. For example, a bill from 2011 on designation of apartments for social housing was classified as a provision, although the bill requires private developers to allocate 8% of any residential development for social housing. This is because, the bill’s explanatory notes emphasize the active role of the government in implementing it: “the government will purchase the dwellings allocated for social housing; The purchase will be at the price that would be obtained from the sale of the same apartment from a voluntary seller to a voluntary buyer, as determined by the government appraiser or whoever he authorized”.

A third challenge was acknowledging that not all bills are created equal. Some proposals suggest light and narrow changes, while others proposed draconian and radical ones. We decided to give all the bills equal weight to try to capture the larger picture.

We explained to our readers that this is not a legal analysis. We did not evaluate existing laws, neither their effects. Our research is a cumulative-aggregative analysis of law proposals, most of which were never enacted. We examined the volume of housing-related bills, and the percentage of approved bills. We also classified the bills thematically and observed the variations overtime. The analysis of the laws, their specific contribution and impact are beyond the scope of this research and require a separate in-depth analysis.

5. Analysis of Housing-Related Bills by Decade

In this section, we examine the housing-related bills proposed between the years 1948 and July 2019, divided into seven decades. In each decade we analyze the categories described above. We also examine the dominant political-economic regime of each decade and changes that occurred. We present the story of each decade, to understand the changes in housing legislation over time.

5.1. First Decade—The 1950s

Israel was established in 1948, initiating its legislative work in January 1949. Israel was declared a social-democratic welfare regime and remained such for the first three decades (1950s–1970s), allocating budgets for social services, public education, public hospitals and public housing; and creating the National Insurance Institute, the basis for the nationwide organizational infrastructure of social services [

9,

45].

Within three years of Israel’s establishment, a massive wave of immigration doubled the population (from 717,000 in October 1948 to 1.4 million in October 1951) [

46]. Urging the authorities to house immigrants in public housing [

38]. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s public housing comprised about 60% of all residential units and over 50% of all housing construction [

47,

48,

49,

50,

51].

However, the state’s massive involvement in the housing sector was not reflected in the bills submitted during this decade. Our study reveals that during the first decade, the Knesset’s work on housing-related-bills focused on protections. 68% of the proposed laws were negative rights including amendments of the Tenant Protection Law, laws protecting immigrants and soldiers’ rights (target populations) and regulation of condominiums (3 of 22 bills, 14%). The 32% rest were positive bills meant to enable the state to obtain loans to subsidize the construction of residential units for immigrants. In terms of quantity, the majority of proposed bills (19 of 22, 86%), were enacted and 90% of them were governmental initiatives.

These findings were surprising since the government played an active role on the housing scene in this decade. However, these were the years of the state’s establishment. Broad protections (negative-rights legislation) were appropriate for a democratic state at the outset, which begins to enact the basic principles of its’ civil rights and protections. In a state that was in charge of massive provision, the remaining concerns were protections.

5.2. Second Decade—The 1960s

During the second decade, substantial waves of immigrants continued to arrive in Israel, totaling more than 200,000 individuals in the first half of the 1960s [

46].

The absolute number of housing-related bills decreased compared to the previous decade (from 22 to 14). According to our findings, during this second decade parliamentary work promoted again protections or negative rights (100%); only 50% were enacted. Most of these bills (12 of 14, 86%) were amendments to the Tenant Protection Law. Enacted laws included an amendment to the condominium law concerning the registration of an apartment. Unapproved bills included a proposal to privatize public housing units (classified as negative). This bill was eventually enacted (in a different format) in the 1990s, when Israel’s political economy had changed. About half of the bills were private initiatives, but only a single of these was enacted; all but one of the government-initiated bills were enacted.

5.3. Third Decade—The 1970s

In the 1970s, as immigration declined, public-housing construction also dropped to an estimated 30% of all building starts. In this period, the government switched from supporting housing construction (supply side) to offering financial incentives for housing ownership through subsidized mortgages (demand side) [

52].

During this decade, the percentage of enacted bills dropped from half to a third (5 of 16, 31%). As in previous decades, all bills enacted were protections (negative), mainly amendments to the Tenant Protection Law concerning rental fees (1 of 7, 14%). Of two additional bills regarding rental, the Knesset enacted one, the Rent and Lending Act, which regulates property use without granting ownership, regardless of the fee. Three enacted bills pertain to the Income Tax Act, offering tax exemption for those who let a residence (Tolls and Taxes category). Four bills, offering provisions and classified as positive, proposed state-allocated resources to build housing for young couples and married soldiers; none of these bills was enacted. In this decade, only governmental bills were enacted (5 of 7, 71%).

5.4. Fourth Decade—The 1980s

The 1980s marked an era of transition in Israel as it did in many parts of the world, shifting towards a capitalist state dominated by neoliberal rationalities, institutions, and practices [

53]. Neoliberalism is characterized by economies dominated by a free market, operating in a deregulated and privatized environment [

54,

55,

56].

In Israel, the shift to a neoliberal economy was accompanied by privatizing of public companies, curbing organized labor, implementing fiscal austerity mechanisms, and retrenching of the welfare state [

10,

11]. In the mid-1980s, the government began the privatization of public housing [

48,

49,

50,

51].

During this decade, 21 bills were proposed, all of them presenting negative rights, protection. Additional amendments to the Tenant Protection Law were proposed, procedures defining the majority needed for condominium renovation, and tax benefits for elderly that rent their apartment due to entering a nursing home. Bills spread between four categories: protections (8 of 21); taxes and tolls (8 of 21); rental (3 of 21); and condominiums (2 of 21) (see

Appendix B). Only four bills were enacted—three governmental bills dealing with protections and one private bill in the condominium category.

5.5. Fifth Decade—The 1990s

The 1990s, saw conflicting trends with regard to the government intervention in housing matters. At the beginning of the 1990s, a mass immigration of nearly one million people from the former Soviet Union created an urgent need for more housing, leading the government to resume the construction of public housing [

53,

57]. In the mid-1990s, with the slowing immigration, it suspended new construction, continued the privatization of public housing, and enacted two public housing laws: The Public Housing Law (Acquisition Law), and the Public Housing Tenant Rights Law, both laws are explained below.

The massive wave of immigration effected the Knesset’s work, and was expressed in a dramatic increase in the number of housing-related bills proposed: 171 bills, eight times the number proposed in the previous decade, and only 19 (11%) of them enacted (19 of 171). Not only did the number of bills go up, the variety of themes addressed increased significantly from four categories to 10, and the content of the bills in some categories changed. In the category of target population, for example, most of the bills referred to new immigrants—building temporary housing for them or housing them in Jewish settlements in the Samaria and Gaza areas, with state subsidies.

Unlike previous decades, this decade saw 36% (62 of 171) of the housing-related bills address provisions (positive rights). Most dealt with state loans for new immigrants or for public construction of new-immigrant housing. The four provisions enacted dealt with state loans for new immigrants.

The majority of the enacted bills (15 of 19) included negative rights, most of them in the category of ‘tolls and taxes’ dealt with income-tax exemptions on rental income and betterment tax on new apartments sold. As to the thematic group ‘public housing’, the two enacted bills on the subject were negative. The first, and more famous, is the Public Housing Act of 1998, which encouraged the privatization of public housing units by offering tenants beneficial conditions (discounts of up to 90%) in purchasing the apartments they lived in. The second, the Public Housing Tenant Rights Act, deals with protections of public housing tenants and their families in various cases, for example, a death in the family.

We also found two new thematic categories in this decade. The first is “Planning and Construction Law” as parliament members explored the possibility of promoting housing generation through amendments to the Planning and Construction Law, 1965 that later became increasingly used. The second category “Other” (11 of 171), included particular bills that could not be included in any other category; such as a sale ban of housing to foreigners, and conditions for tenders for the development of residential units in nationally owned lands. None of the bills in these two categories was enacted.

Surprisingly, during this decade, unlike previous decades, almost all the bills proposed (160 of 171, 94%) and most of the bills enacted (10 of 19, 53%) were privately initiated. Out of these, a single provision offered loans for immigrants. Only 11 government bills were submitted, and nine were approved: six concerned tax relief, classified as negative, and three concerned housing loans for immigrants, classified as positive.

5.6. Sixth Decade—The 2000s

The early millennium in Israel, was portrayed by Benchetrit (2014) [

58] as “the lost decade” of housing policy as intensified neoliberalism allowed market forces to determine housing-construction locations, quantity, price, and target clientele, average apartment size and construction standards. The most tangible consequence of the do-nothing government housing policy was the dramatic rise in housing prices. From 2007 to 2013, housing prices rose precipitously by over 70% in real terms, adjusting for changes in the Consumer Price Index [

59].

Our findings showed a 45% increase in the total number of bills proposed compared to the previous decade. Very few government-initiated bills were proposed (9 of 242, 4%) and they were all protections. Seven of them were enacted, including protection for housing-loan takers, tax relief, and two laws on earthquake preparedness (TAMA 38) [

60,

61,

62].

The 233 private bills were diverse and included a number of new categories and themes that first appeared during the sixth decade. A quarter of all private bills (61 of 236) contained provisions (positive rights). These bills included the affordable housing bill, a practice benchmarked from abroad, under which developers would have to sell 30% of the built housing units for an affordable price up to 30% of the dweller’s income; the social-housing bill, which required developers to allocate 10% of all residential development to social-housing units and required the government to purchase these apartments at market price; the rental construction bill, which required the state to build housing units for rental units, allocate 40% of all public construction for rental, and make building permits for private construction conditional on the allocation of 10% for rental; and a construction bill for single new immigrants, based on a similar mechanism to that of the rental construction bill.

The private and positive bills also expanded their target populations. In addition to the traditional target populations (soldiers, children in need, and people with disabilities) the bills included new target populations, such as casualties of the Chernobyl disaster, labor migrants, and Israeli citizens evicted from the Gaza Strip in summer 2005. A single private and positive bill out of 61 was enacted—an amendment to the Public Housing Tenant Rights Act requiring the state to allocate funds to install solar water heaters in public housing units.

The majority of private negative rights pertained to tolls and taxes, loans, or mortgages. Seven were enacted, six providing amendments to the Housing Loans Act, and one concerning guarding in condominiums. Another innovation attributed to this decade were eight consecutive proposals to anchor a fundamental right to housing, recognizing housing as a human right. These unapproved proposals were reflections of a larger constitutional revolution in the process of expanding a judicial review of the Knesset’s laws [

63].

5.7. Seventh Decade—The 2010s

The seventh decade is characterized by the centrality of housing. The skyrocketing cost of living, the great increase in housing costs, and the lack of affordable housing sparked the country’s largest social protest ever, in the summer of 2011. Demonstrations and protests were held throughout the country [

3,

14,

17].

Following the 2011 protest, the government made a series of decisions to increase the supply of housing units to lower prices [

15,

60,

64,

65,

66]. Among these the government signed an “umbrella agreement” (Heskem Gag in Hebrew) with local authorities to quickly increase the supply of housing units; establishing the National Housing Committee to accelerate planning procedures; setting up the Urban Renewal Authority to address urban renewal development, both nationally and locally; and granting rights to build on publicly owned lands to developers so as to lower the price of housing units as part of Target Price and Resident’s Price programs. It should be note, that in Israel, 93% of the lands are nationally owned [

67,

68].

It would seem that the centrality of housing was reflected in the substantial increase in the number of housing-related bills proposed during this decade (446 of 933), which was half of all housing-related bills proposed over the seven decades. However, as in the previous decade, only 4% (19 of 446) were government bills. Moreover, only 6% (25 of 446) of all the bills were enacted, and only 1.7% of the total enacted bills were housing-related (

Table 1). Of the enacted bills, only one was positive: loans for housing. Five enacted government bills, resulting directly from the social protests, established committees (known as VADAL and VATMAL) to promote massive and accelerated housing construction through a fast track.

Of all the submitted bills, 96% (427 of 446) were private initiatives and included a wide range of themes and categories. The most contested subject was public housing; it included 105 bills of which five were enacted; all included negative rights, protecting the tenants of public housing in case of divorce or enabling them to access public housing information.

During this period, the percentage of private positive bills increased substantially to almost 40% (168 of 446). Most of the bills were variations or duplicates of bills submitted in previous decades, and more than half were public- or social-housing affairs. Of particular interest are six bills concerning housing alternatives for disadvantaged populations living in three neighborhoods undergoing urban regeneration processes (Givat Amal and Argazim in Tel Aviv and the Yemenite Valley in Jerusalem) [

69]. None of these bills were enacted.

The private bills classified as negative (261 of 427) included mainly protections or procedures regarding loans, mortgages, and tolls and taxes. For the first time, a large number of bills addressed equality of opportunity in various areas. In the protections category, most of the bills (20 of 27) dealt with the requirement to prohibit housing discrimination or with equal opportunity in the place of residence; under the rental category, for the first time there were bills calling for the enactment of a Fair Rent Act (7 of 27). The basic bill concerning the right to housing was introduced seven times, and 17 different bills were introduced regarding affordable housing. But the only bill enacted was a private bill on affordable housing that an amendment of the Planning and Building Act. The amendment recognized affordable housing as a public land use, thus enabling authorities to designate land for affordable housing construction. The law did not define affordable housing.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

This study was an empirical cumulative-aggregative analysis to examine (quantitatively and qualitatively) the scope and content of housing-related bills proposed in the Knesset since its establishment in 1948 until today (2019). The bills were classified according to five dimensions: Decade (1–7), Status (enacted/not enacted), Initiator (private, government), Theme (12 subcategories) and Type of rights (positive/negative). We used the classical theoretical framework that distinguishes between positive and negative rights, that reflects well the state’s role and willingness to invest (or not) in the provision of various public services, and therefore is an indicator of the state political-economic regime. The literature attributes positive-rights legislation (provisions) to social democracies or welfare states, and negative-rights legislation (protections) to neoliberal states [

18,

21,

22].

We presented the key findings on the five dimensions. Then wwe examined the significance of the findings for the question of whether legislation was a successful parliamentary task to promote housing rights in a democratic state.

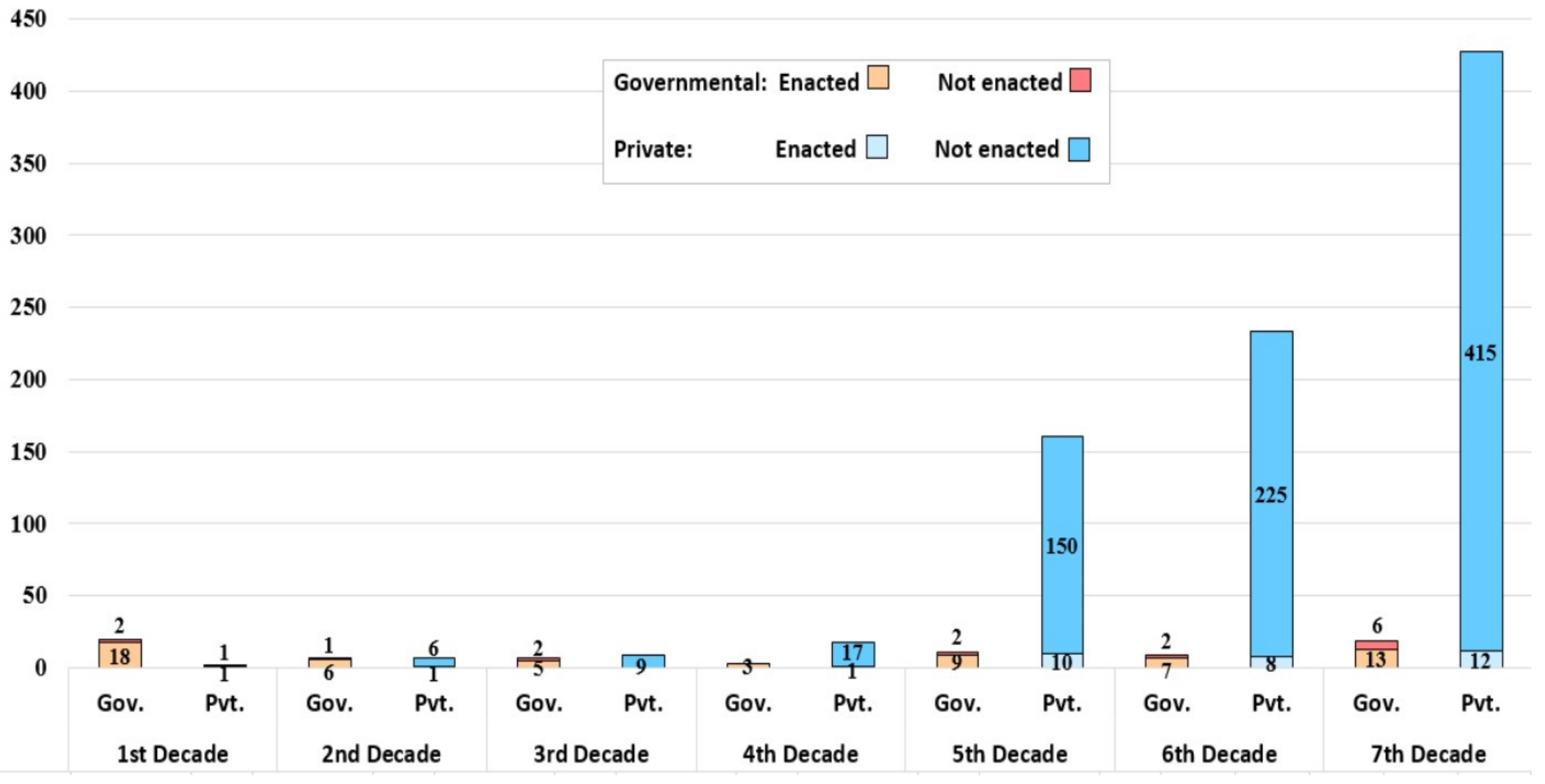

A total of 932 housing-related bills were proposed over seven decades. The most notable finding was the significant increase in the number and percentage of private-initiative bills.

Figure 2 shows a similarly small and unchanged number of governmental proposals in the first and seventh decades. The number of private proposals, however, increased significantly, especially starting in the 1990s (fifth decade). Of all enacted bills, 35% (33 of 94) were private. Only two were enacted in the first two decades, and all others from the 1990s onward. These findings might be overstated, because some private bills were processed in the Knesset with government approval or even blessing. Nevertheless, it may have implied a shift in the Knesset toward more individual parliamentary work by MKs. A recent study found that the number of private bills introduced in Israel was very large in comparison to the number introduced in other countries [

70].

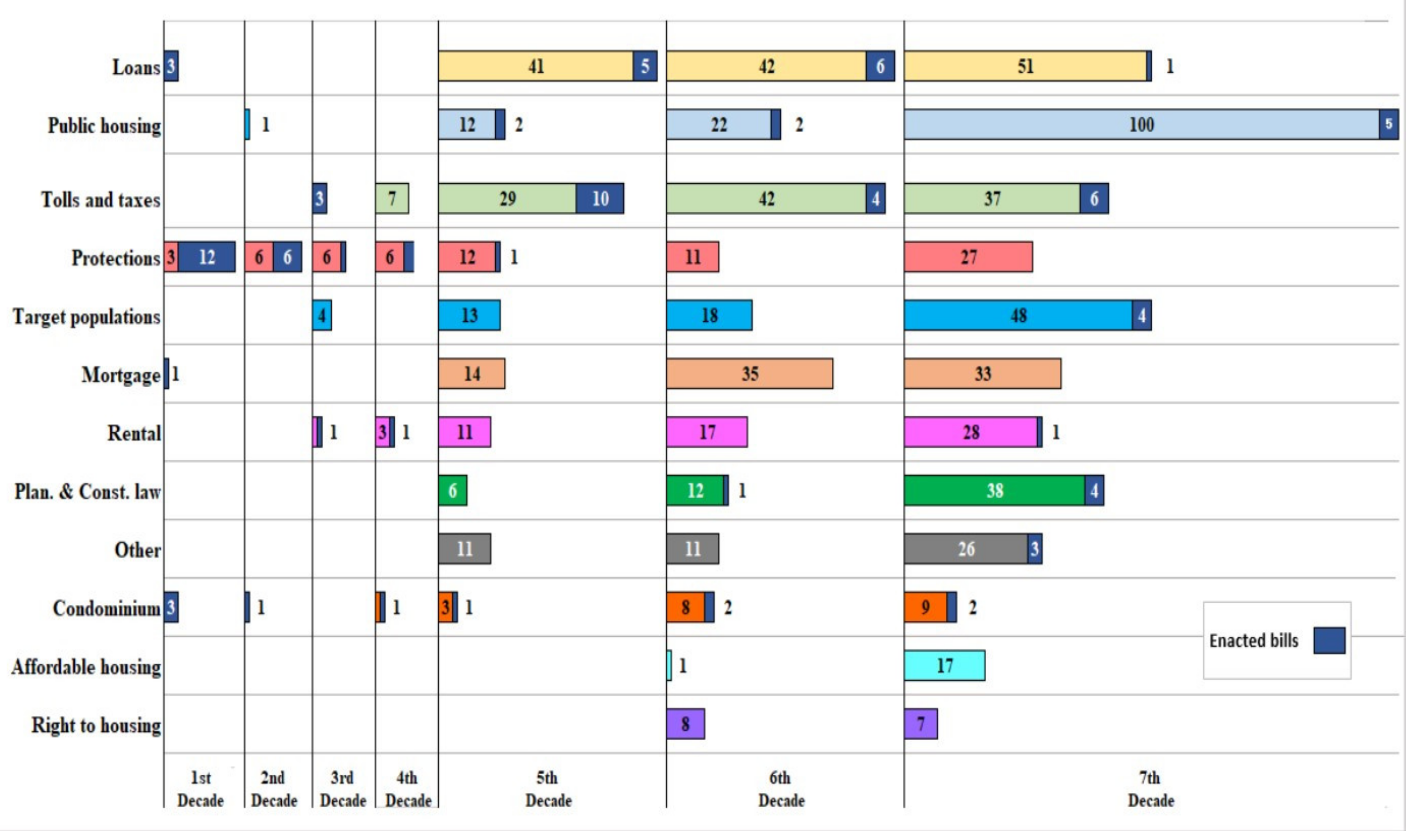

Another interesting finding related to the variety of themes the bills addressed, as shown in

Figure 3. The themes became diverse in recent decades, especially since the 1990s. During the first four decades, thematic groups ranged among four to five themes, focusing on the category protections. Since the fifth decade, the number has expanded to 10–12 themes.

The significant increase in private bills, and the thematic range, may have been attributed to political changes, and political fragmentation that has characterized Israel in the last three decades. The multiplicity of parties running for general election led to a sectoral parliament and to political instability [

71].

The most interesting finding, which contradicts the literature, related to the distinction between positive and negative rights. The research findings showed counterintuitive relations between the state’s dominant political economy and the type of housing-related rights it promoted (

Figure 4).

Despite Israel’s social-democratic and welfare state roots, 90% of its enacted housing legislation promoted negative rather than positive rights. Looking at the bills proposed, there was a greater balance—68% of all housing-related bills included negative rights, and 32% addressed positive rights.

In the first four decades (1950s–1980s), when Israel was a social-democratic state, the Knesset enacted only three bills containing positive rights, which were only 3% of all enacted bills, and 33% of all positive enacted bills. All three bills concerned state loans for the construction of housing for immigrants. These findings were seemingly surprising knowing that the government was a powerful player on the housing scene during the decade. However, as previously mentioned, since the state was in charge of massive provision, the remaining concerns were inevitably aspects of protection. In total, only 3% of all positive bills introduced were introduced by the end of the 1980s.

Since the 1990s, when the overall neoliberal policy became more entrenched, 67% (6 of 9) of the positive bills were enacted. Most of them (4 of 6) were enacted during the 1990s as a result of the mass immigration from the former Soviet Union and required government investment to provide housing for the new immigrants. The enacted bills dealt mainly with loans the government was required to provide housing for new immigrants. Most (8 of 9) of the enacted public housing bills were negative rights, dealing with protections of the public housing tenant or with conditions for the privatization of public housing units.

These interesting findings raise two sets of questions: First, how can these findings be explained? Did not the political-economic regime effect housing legislation?

A possible explanation for some of the findings is that regardless of the political-economic regime, negative rights (protections) did not require large investments by the central government and therefore obtain the majority needed for enactment with greater ease. An in-depth examination of the positive legislation over the years indicates that most positive legislation (7 of 9, 78%) was enacted during the first (1950s) and fifth (1990s) decades. Both periods were characterized by mass immigration, which explains the similarities in creating state loans to provide housing for new immigrants. Interestingly, Hananel (2019) [

50] unfolded the apparent housing-related anomaly in the 1990s by claiming that following the mass immigration from the former Soviet Union, the neoliberal government had to act in an emergency state to approve positive legislation and to allocate resources to provide housing. However, as the decade progressed and the wave of immigration receded, the need for positive legislation fell and the government reverted to a neoliberal policy [

72]. Evidence of this can be seen in two negative laws on public housing passed towards the end of the fifth decade [

48]. If we exclude the positive immigrants legislation of the 1990s, we find only two approved positive bills over the last three decades (from the 1990s to the present). Hence, although we did not find a correlation between the political-economic regime and the type of housing-related legislation (protections vs. provisions), the influence of the dominant political economy on such legislation cannot be ruled out.

Another possible explanation for the rise in negative rights bills was the increasing importance of property rights in general and private property in particular in countries with a neoliberal political economy, such as in Israel.

On the other hand, it is also reasonable to assume that the growing socioeconomic disparities and the rising cost of living, as it has been the case in Israel since the 2000s, will encourage MKs to introduce corrective measures like private bills that promote positive rights, as previously seen. During these decades, for the first time, social affairs came to the fore in housing-related bills; examples included housing equality, the demand for fairness and nondiscrimination in housing, and recognition of the fundamental right to housing. However, none of these bills was enacted.

We were surprised to find out that although the social protest of 2011 dealt directly with housing issues, only five new laws were passed in the seventh decade as a direct result of the protest, and they all concerned establishing committees (the VADAL and the VATMAL) to promote massive and accelerated (private) housing construction through a fast track. We did not find that new bills encouraged the investment of resources in housing or substantial government intervention. It should be noted, that from a methodological standpoint an empirical analysis of the bills (such as we did), made it hard to reach further findings regarding the influence of the social protest on legislation. We can assume that the social protest was very much alive in various parliamentary discussions. Moreover, as we already mentioned, we referred each bill equally, and did not give weight to the impact of the bill and the significant reform it may lead to. Thus, future research is required on the matter.

To sum up, now we ask: what can be learned from the research findings about the contribution of the legislative branch to housing-law making and to the promotion of housing rights? Furthermore, what are the broader implications?

Our research findings showed that a very low percentage of housing-related bills in Israel (positive housing rights in particular) became law. Even following the largest social protest in Israel’s history in 2011, the Knesset did not enact many bills that required the investment of resources for housing. We do know that following 2011 summer protest, the government made many housing policy decisions using a variety of policy tools aimed at different populations [

16,

63,

66], but only a minor part of these policy decisions completed the legislative process.

These finding suggest that the promotion of substantial rights may have been abolished in parliament by decisions of ad hoc coalitions and party considerations against the interests of the public, especially the disadvantaged. At the practical level, this trend is reflected in a planning and housing policy that ignores the needs of a variety of disadvantaged populations in society [

65,

69,

73,

74,

75,

76].

Nowadays, in the face of the global housing affordability crisis, the need to promote housing rights, especially for the most disadvantaged in society is pressing and evident.

In our normative view, states are obliged to react and ensure that every person has access to affordable housing; to guarantee that people can lead private lives, with adequate living conditions, and in an environment that is accessible to employment, infrastructure, and social services. Favorable laws demand approval. Thus, it is both interesting and important to examine the role of housing bills and its ramifications in other parts of the world.