Rangeland Land-Sharing, Livestock Grazing’s Role in the Conservation of Imperiled Species

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

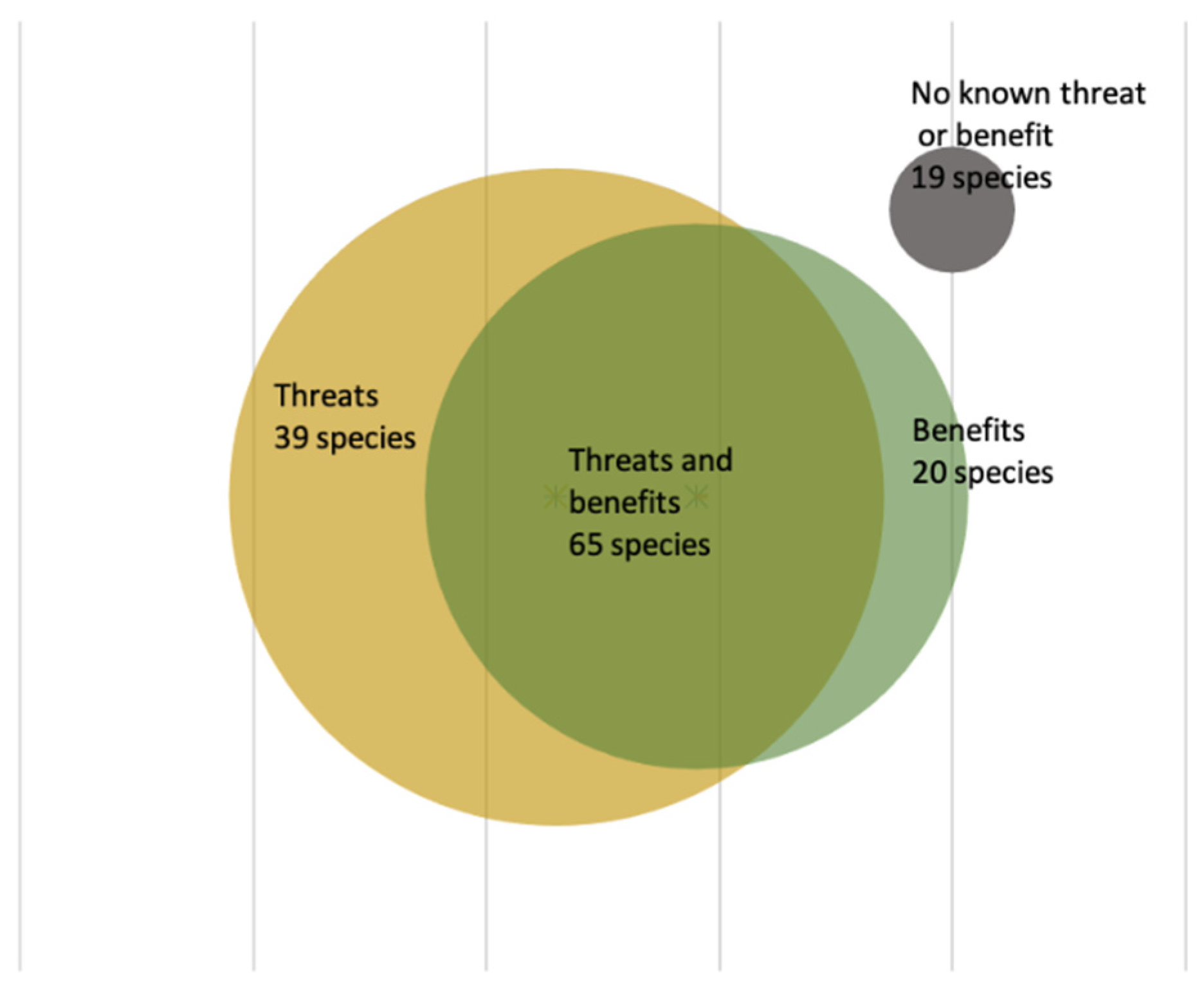

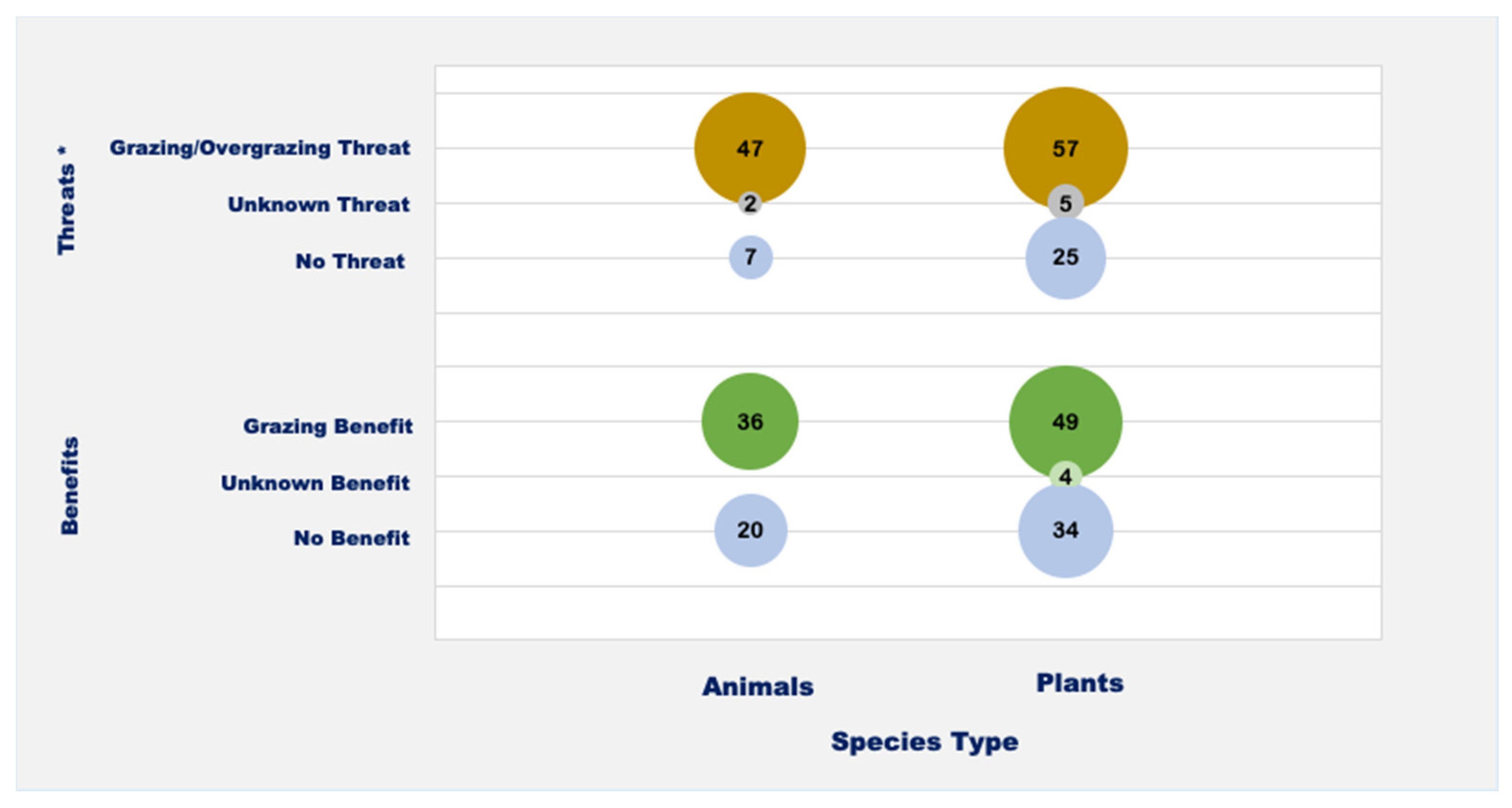

3.1. Grazing’s Impact by Species Type

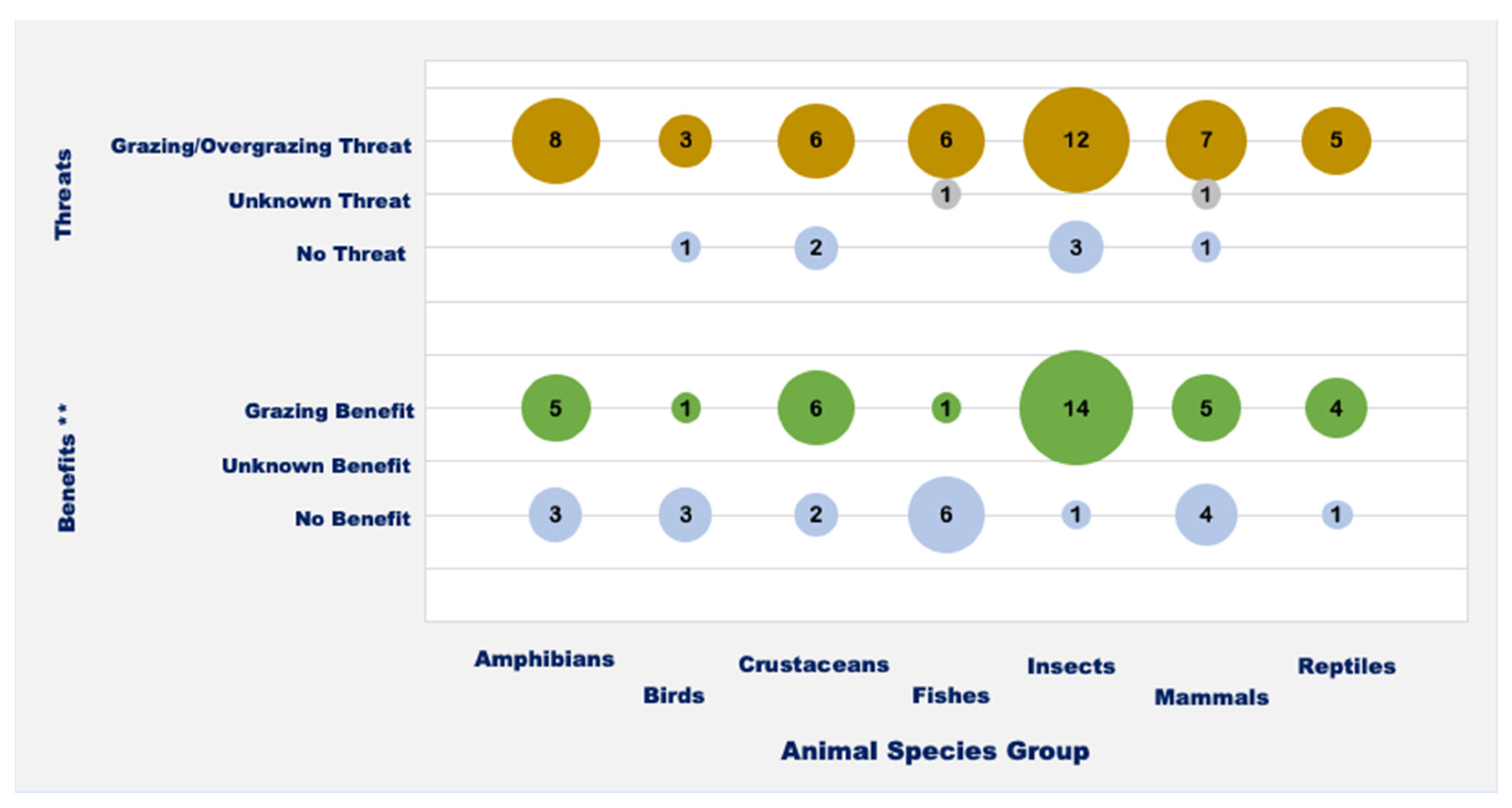

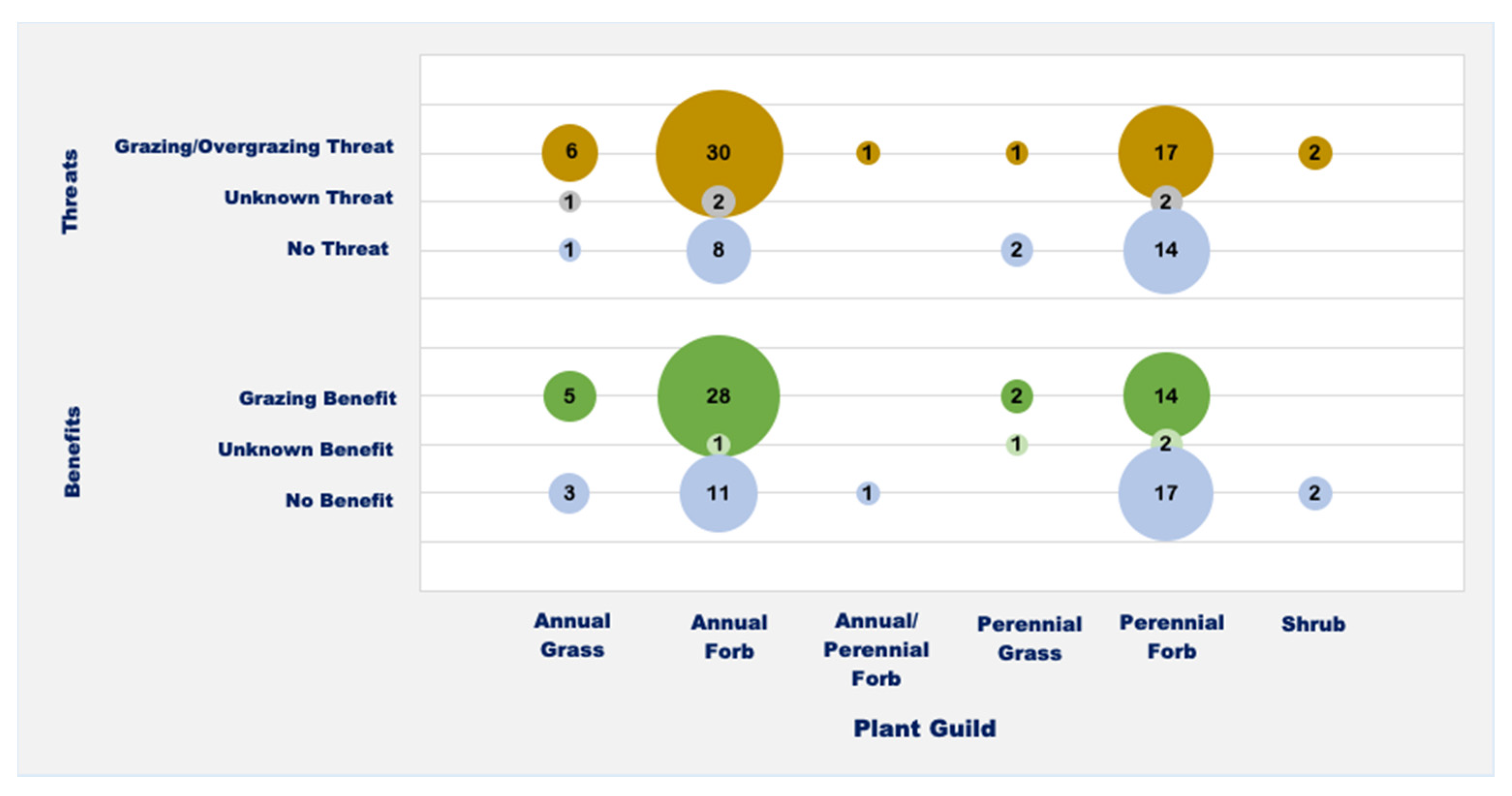

3.2. Grazing’s Impact by Animal Species Group and Plant Guild

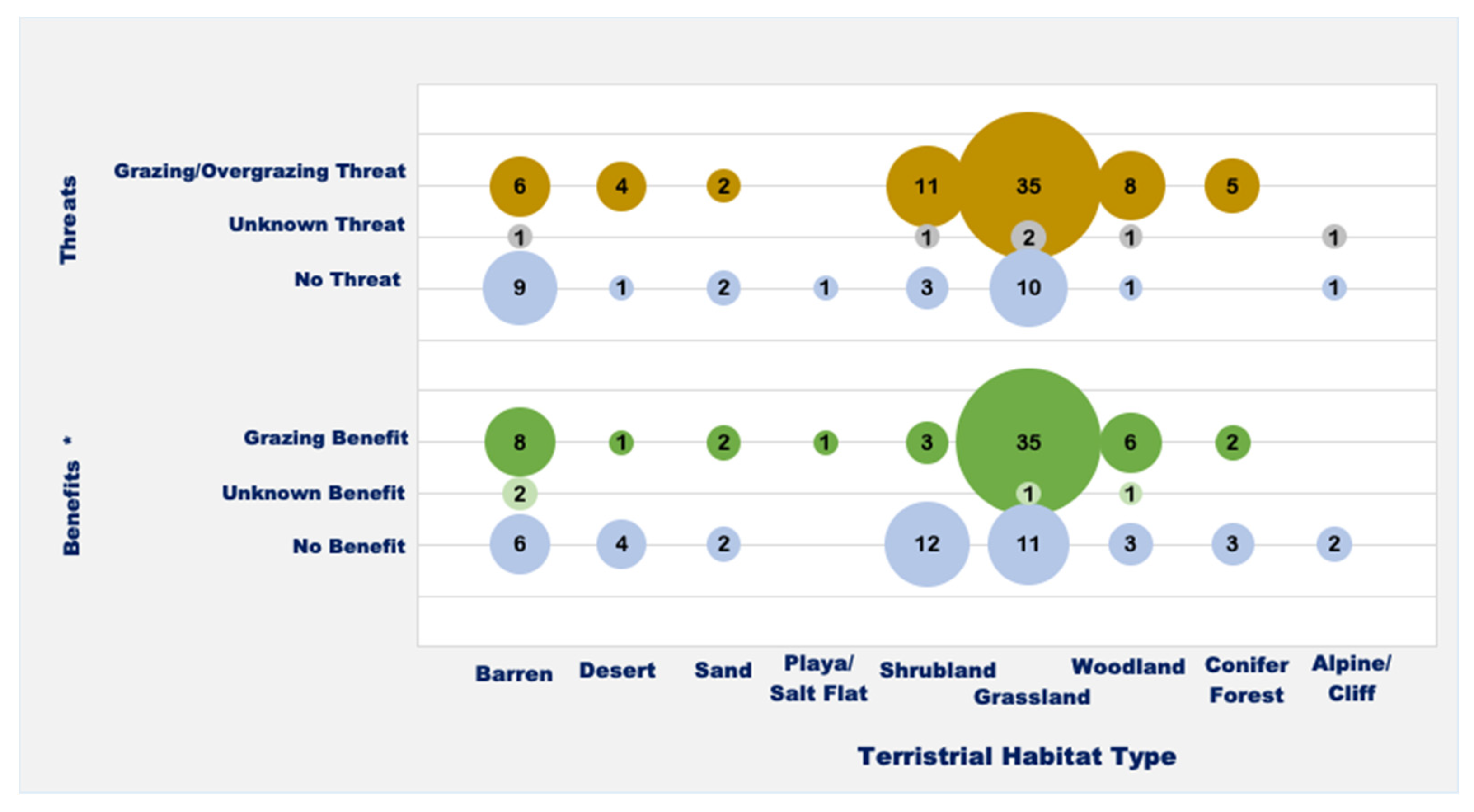

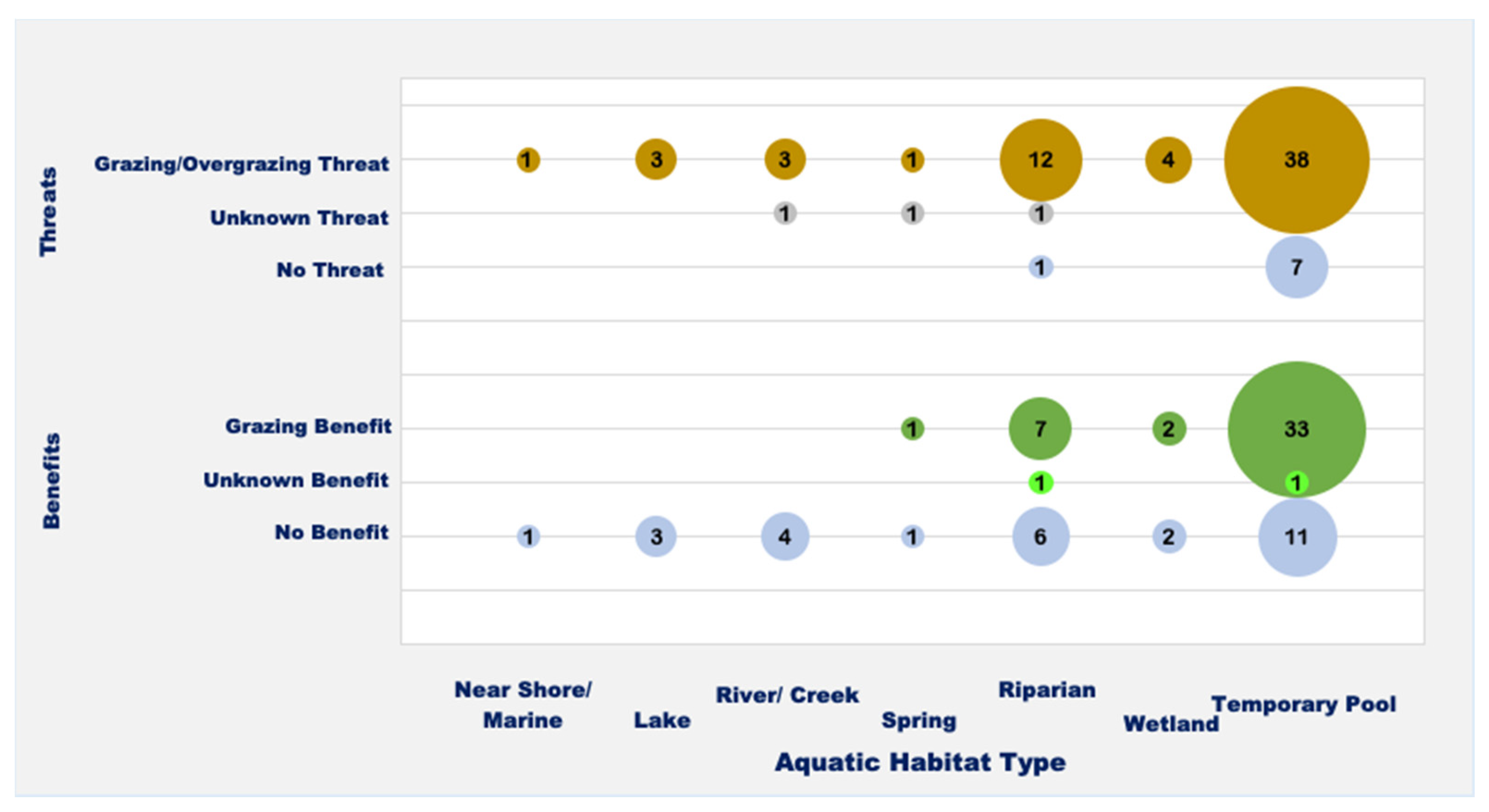

3.3. Grazing’s Impact by Ecosystem

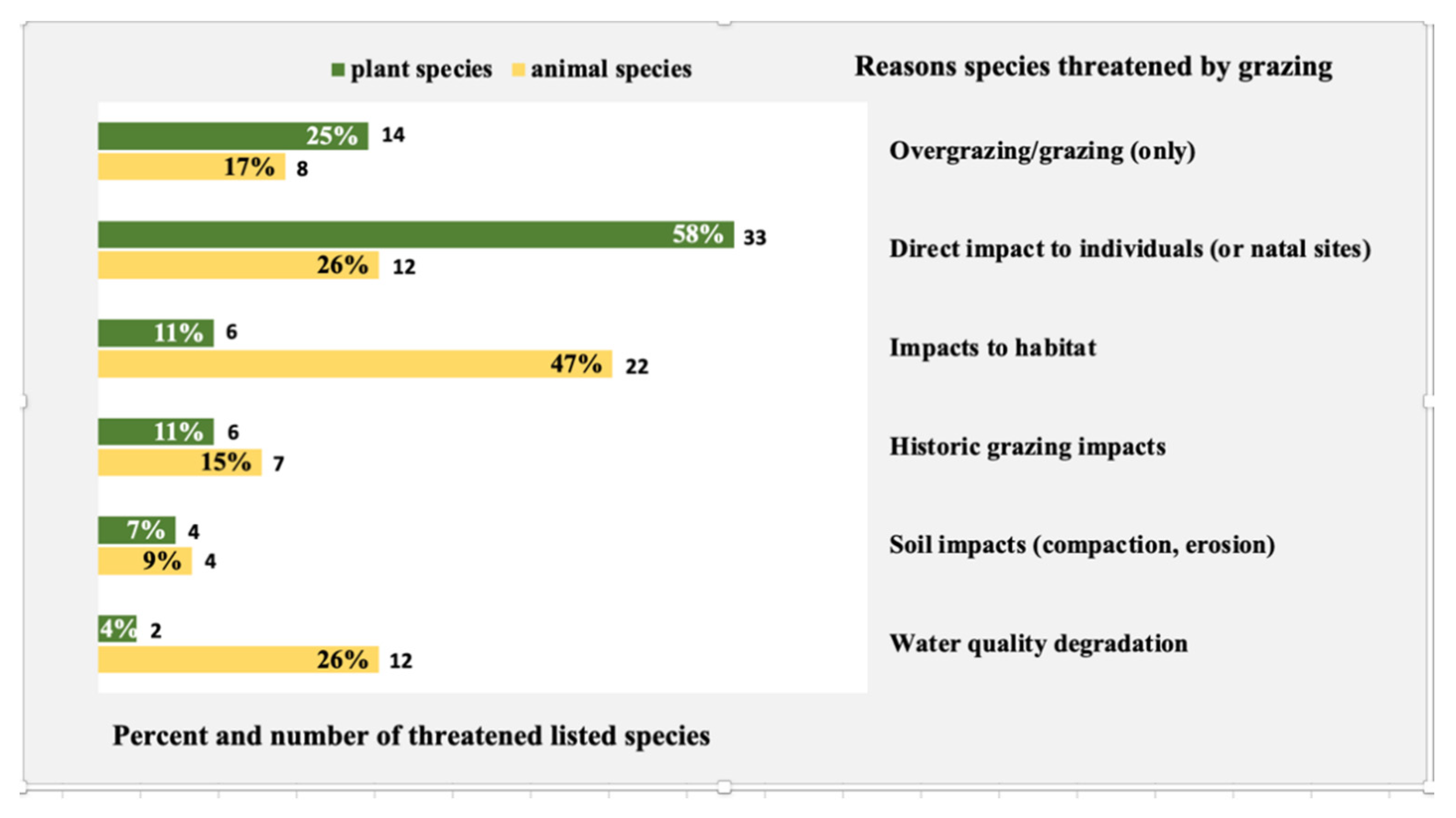

3.4. The Reasons Livestock Grazing Threatens Species

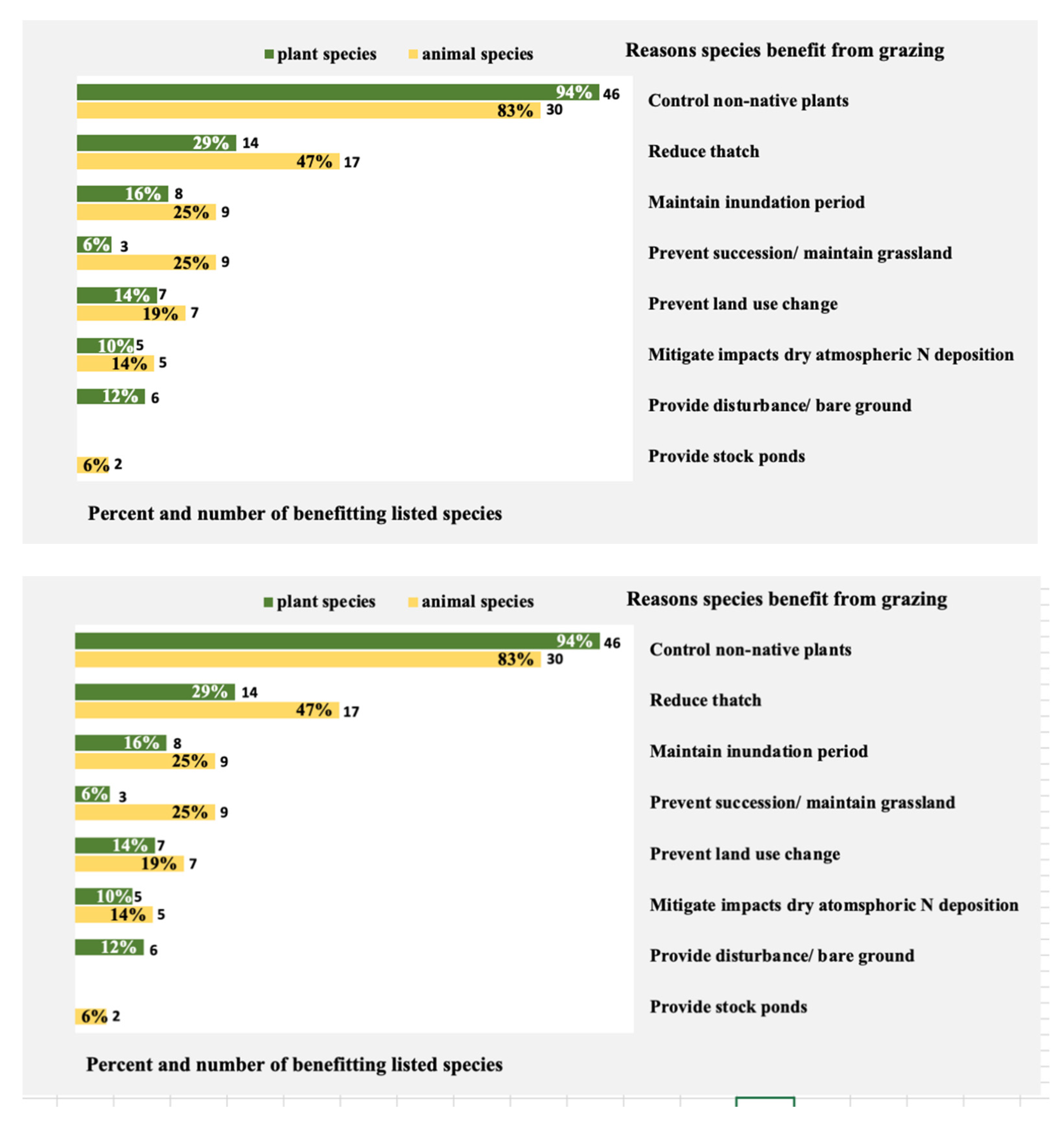

3.5. The Reasons Livestock Grazing Benefits Species

4. Discussion

4.1. Value and Limitations of Best Available Science and the USFWS Listings

4.2. Proper Management to Minimize Threats

4.3. Grazing Supports Conservation Reliant Species

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Holechek, J.L.; Piper, R.D.; Herbel, C.H. Range Management: Principles and Practices, 6th ed.; Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sayre, N.F.; Carlisle, L.; Huntsinger, L.; Fisher, G.; Shattuck, A. The role of rangelands in diversified farming systems: Innovations, obstacles, and opportunities in the USA. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galyean, M.L.; Ponce, C.; Schutz, J. The future of beef production in North America. Anim. Front. 2011, 1, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plieninger, T.; Ferranto, S.; Huntsinger, L.; Kelly, M.; Getz, C. Appreciation, use, and management of biodiversity and ecosystem services in California’s working landscapes. Environ. Manag. 2012, 50, 427–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charnley, S.; Sheridan, T.E.; Nabhan, G.P. (Eds.) Stitching the West Back Together: Conservation of Working Landscapes; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Green, R.E.; Cornell, S.J.; Scharlemann, J.P.; Balmford, A. Farming and the fate of wild nature. Science 2005, 307, 550–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, J.; Abson, D.J.; Butsic, V.; Chappell, M.J.; Ekroos, J.; Hanspach, J.; Kuemmerle, T.; Smith, H.G.; von Wehrden, H. Land sparing versus land sharing: Moving forward. Conserv. Lett. 2014, 7, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcove, D.S.; Rothstein, D.; Dubow, J.; Phillips, A.; Losos, E. Quantifying threats to imperiled species in the United States. BioScience 1998, 48, 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czech, B.; Krausman, P.R.; Devers, P.K. Economic associations among causes of species endangerment in the United States: Associations among causes of species endangerment in the United States reflect the integration of economic sectors, supporting the theory and evidence that economic growth proceeds at the competitive exclusion of nonhuman species in the aggregate. AIBS Bull. 2000, 50, 593–601. [Google Scholar]

- Howell, H.J.; Mothes, C.C.; Clements, S.L.; Catania, S.V.; Rothermel, B.B.; Searcy, C.A. Amphibian responses to livestock use of wetlands: New empirical data and a global review. Ecol. Appl. 2019, 29, e01976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schieltz, J.M.; Rubenstein, D.I. Evidence based review: Positive versus negative effects of livestock grazing on wildlife. What do we really know? Environ. Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 113003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolome, J.W.; Allen-Diaz, B.H.; Barry, S.; Ford, L.D.; Hammond, M.; Hopkinson, P.; Ratcliff, F.; Spiegal, S.; White, M.D. Grazing for biodiversity in Californian Mediterranean grasslands. Rangelands 2014, 36, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germano, D.J.; Rathbun, G.B.; Saslaw, L.R. Effects of grazing and invasive grasses on desert vertebrates in California. J. Wildl. Manag. 2012, 76, 670–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marty, J.T. Loss of biodiversity and hydrologic function in seasonal wetlands persists over 10 years of livestock grazing removal. Restor. Ecol. 2015, 23, 548–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyke, C.R.; Marty, J. Cattle grazing mediates climate change impacts on ephemeral wetlands. Conserv. Biol. 2005, 19, 1619–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, S. Cars, cows, and checkerspot butterflies: Nitrogen deposition and management of nutrient poor grasslands for a threatened species. Conserv. Biol. 1999, 13, 1476–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitschmidt, R.; Stuth, J. Grazing Management: An Ecological Perspective; Timber Press: Portland, OR, USA, 1991; p. 259. [Google Scholar]

- Koerner, S.E.; Smith, M.D.; Burkepile, D.E.; Hanan, N.P.; Avolio, M.L.; Collins, S.L.; Knapp, A.K.; Lemoine, N.P.; Forrestel, E.J.; Eby, S.; et al. Change in dominance determines herbivore effects on plant biodiversity. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 2, 1925–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milchunas, D.G. Responses of Plant Communities to Grazing in the Southwestern United States; Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-FTR-169; US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Augustine, D.J.; McNaughton, S.J. Ungulate effects on the functional species composition of plant communities: Herbivore selectivity and plant tolerance. J. Wildl. Manag. 1998, 62, 1165–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcove, D.S.; Bean, M.J.; Long, B.; Snape, W.J.; Beehler, B.M.; Eisenberg, J. The private side of conservation. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2004, 2, 326–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, N.; Mittermeier, R.A.; Mittermeier, C.G.; Da Fonseca, G.A.; Kent, J. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 2000, 403, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burge, D.O.; Thorne, J.H.; Harrison, S.P.; O’Brien, B.C.; Rebman, J.P.; Shevock, J.R.; Alverson, E.R.; Hardison, L.K.; RodrÍguez, J.D.; Junak, S.A.; et al. Plant diversity and endemism in the California Floristic Province. Madroño 2016, 63, 3–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, H.G. Sources of the Naturalized Grasses and Herbs in California Grasslands. In Grassland Structure and Function; Huenneke, L.F., Mooney, H.A., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1989; pp. 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Mooney, H.A.; Hamburg, S.P.; Drake, J.A. The Invasions of Plants and Animals into California. In Ecology of Biological Invasions of North America and Hawaii; Mooney, H.A., Drake, J.A., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1986; pp. 250–272. [Google Scholar]

- Zeder, M.A. Domestication and early agriculture in the Mediterranean Basin: Origins, diffusion, and impact. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 11597–11604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simberloff, D.; Martin, J.L.; Genovesi, P.; Maris, V.; Wardle, D.A.; Aronson, J.; Courchamp, F.; Galil, B.; García-Berthou, E.; Pascal, M.; et al. Impacts of biological invasions: What’s what and the way forward. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2013, 28, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huntsinger, L.; Bartolome, J.W.; D’Antonio, C.M. Chapter 20. Grazing Management of California Grasslands. In Ecology and Management of California Grasslands; Corbin, J., Stromberg, M., D’Antonio, C.M., Eds.; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2007; pp. 233–253. [Google Scholar]

- Huntsinger, L.; Bartolome, J.W. Cows? In California? Rangelands and livestock in the golden state. Rangelands 2014, 36, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, S.W. A Rancholabrean-age, latest Pleistocene bestiary for California botanists. Four Seas. 1996, 10, 4–34. [Google Scholar]

- Maestas, J.D.; Knight, R.L.; Gilgert, W.C. Cows, condos, or neither: What’s best for rangeland ecosystems? Rangel. Arch. 2002, 24, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Díaz, M.; Tietje, W.D.; Barrett, R.H. Effects of Management on Biological Diversity and Endangered Species. In Mediterranean Oak Woodland Working Landscapes Landscape Series, vol 16; Campos, P., Huntsinger, L., Oviedo Pro, J.L., Starrs, P.F., Diaz, M., Staniford, R.B., Montero, G., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 213–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremen, C. Reframing the land-sparing/land-sharing debate for biodiversity conservation. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2015, 1355, 52–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phalan, B.; Green, R.; Balmford, A. Closing yield gaps: Perils and possibilities for biodiversity conservation. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2014, 369, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butsic, V.; Kuemmerle, T. Using optimization methods to align food production and biodiversity conservation beyond land sharing and land sparing. Ecol. Appl. 2015, 25, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottet, A.; de Haan, C.; Falcucci, A.; Tempio, G.; Opio, C.; Gerber, P. Livestock: On our plates or eating at our table? A new analysis of the feed/food debate. Glob. Food Sec. 2017, 14, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for Conservation Innovation. Defenders of Wildlife, ESA Docs Search. Available online: https://esadocs.cci-dev.org/ (accessed on 10 July 2017).

- United States Fish and Wildlife Service. USFWS Environmental Conservation Online System (ECOS) Species Profiles. Available online: https://ecos.fws.gov/ecp0/reports/species-listed-by-state-report?state=CA&status=listed (accessed on 31 August 2017).

- Natureserve. Available online: http://services.natureserve.org (accessed on 1 May 2019).

- Comer, P.J.; Faber-Langendoen, D.; Evans, R.; Gawler, S.C.; Josse, C.; Kittel, G.; Menard, S.; P yne, M.; Reid, M.; Schulz, K.; et al. Ecological Systems of the United States: A Working Classification of U.S. Terrestrial Systems; NatureServe: Arlington, VA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Franke, T.M.; Ho, T.; Christie, C.A. The chi-square test: Often used and more often misinterpreted. Am. J. Eval. 2012, 33, 448–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Fish and Wildlife Service. Sierra Nevada Bighorn Sheep (Ovis Canadensis Californiana = Ovis Canadensis Sierrae) 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation; United States Fish and Wildlife Service: Ventura, CA, USA, 2008.

- United States Fish and Wildlife Service. Sidalcea keckii, Keck’s Checkermallow, 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation; USFWS: Sacramento, CA, USA, 2012.

- United States Fish and Wildlife Service. Cirsium Fontinale Var. Obispoense, Chorro Creek Bog Thistle, 5-Year Eeview: Summary and Evaluation; USFWS: Ventura, CA, USA, 2014.

- United States Fish and Wildlife Service. Arctostaphylos Pallida, Pallida Manzanita, 5-Year Eeview: Summary and Evaluation; USFWS: Sacramento, CA, USA, 2010.

- United States Fish and Wildlife Service. Cordylanthus Mollis Spp. Mollis, 5-Year Eeview: Summary and Evaluation; USFWS: Sacramento, CA, USA, 2009.

- United States Fish and Wildlife Service. Little Kern Golden Trout (Oncorhynchus Mykiss Whitei), 5-Year Eeview: Summary and Evaluation; USFWS: Sacramento, CA, USA, 2011.

- United States Fish and Wildlife Service. Paiute Cutthroat Trout (Oncorhynchus Clarkii Seleniris), 5-Year Eeview: Summary and Evaluation; USFWS: Reno, NV, USA, 2013.

- United States Fish and Wildlife Service. Kern Mallow (Eremalche Kernensis), 5-Year Eeview: Summary and Evaluation; USFWS: Sacramento, CA, USA, 2013.

- United States Fish and Wildlife Service. Blunt-Nosed Leopard Lizard (Gambelia Sila), 5-Year Eeview: Summary and Evaluation; USFWS: Sacramento, CA, USA, 2010.

- United States Fish and Wildlife Service. Giant Kangaroo Rat, Dipodomys ingens, 5-Year Eeview: Summary and Evaluation; USFWS: Sacramento, CA, USA, 2010.

- United States Fish and Wildlife Service. San Joaquin Kit Fox, Vulpes Macrotis Mutica, 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation; USFWS: Sacramento, CA, USA, 2010.

- United States Fish and Wildlife Service. Santa Cruz Tarplant, Holocarpha Macradenia, 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation; USFWS: Ventura, CA, USA, 2014.

- United States Fish and Wildlife Service. Ohlone Tiger Beetle, Cicindela Ohlone, 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation; USFWS: Arcata, CA, USA, 2009.

- United States Fish and Wildlife Service. Bay Checkerspot Butterfly, Euphydryas Editha Bayensis, 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation; USFWS: Sacramento, CA, USA, 2009.

- United States Fish and Wildlife Service. Lilium Occidentale, 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation; USFWS: Arcata, CA, USA, 2009.

- United States Fish and Wildlife Service. Conservancy Fairy Shrimp, Branchinecta Conservation, 5-Year Review: Summary and Evalution; USFWS: Sacramento, CA, USA, 2012.

- United States Fish and Wildlife Service. Lasthenia Conjugens Contra Costa Goldfields, 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation; USFWS: Sacrmanto, CA, USA, 2013.

- Marty, J.T. Effects of cattle grazing on diversity in ephemeral wetlands. Conserv. Biol. 2005, 19, 1626–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischner, T.L. Ecological costs of livestock grazing in western North America. Conserv. Biol. 1994, 8, 629–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.H.; McDonald, W. Livestock grazing and conservation on southwestern rangelands. Conserv. Biol. 1995, 9, 1644–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’antonio, C.M.; Meyerson, L.A. Exotic plant species as problems and solutions in ecological restoration: A synthesis. Restor. Ecol. 2002, 10, 703–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, R.D.; Bartolome, J.W. Grazing Ecology of California Grasslands. In Ecology and Management of California Grasslands; Corbin, J., Stromberg, M., D’Antonio, C.M., Eds.; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2007; pp. 197–206. [Google Scholar]

- Lowell, N.; Kelly, R.P. Evaluating agency use of “best available science” under the Endangered Species Act. Biol. Conserv. 2016, 196, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belsky, A.J.; Matzke, A.; Uselman, S. Survey of livestock influences on stream and riparian ecosystems in the western United States. J. Soil Water Conserv. 1999, 54, 419–431. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, G. The saga of the Santa Cruz tarplant. Four Seas. 1998, 10, 18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Germano, D.J.; Rathbun, G.B.; Saslaw, L.R. Managing exotic grasses and conserving declining species. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 2001, 29, 551–559. [Google Scholar]

- Briske, D.D.; Derner, J.D.; Milchunas, D.G.; Tate, K.W. An Evidence-Based Assessment of Prescribed Grazing Practices. In Conservation Benefits of Rangeland Practices: Assessment, Recommendations, and Knowledge Gaps; Briske, D.D., Ed.; USDA-NRCS: Washington DC, USA, 2011; pp. 21–74. [Google Scholar]

- Mysterud, A. The concept of overgrazing and its role in management of large herbivores. Wildl. Biol. 2006, 12, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coughenour, M.B.; Singer, F.J. The Concept of Overgrazing and Its Application to Yellowstone’s Northern Range. In The Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem: Redefining America’s Wilderness Heritage; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1991; pp. 209–230. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz, S.; Lavorel, S.; McIntyre, S.; Falczuk, V.; Casanoves, F.; Milchunas, D.G.; Skarpe, C.; Rusch, G.; Sternberg, M.; Noy-Meir, I.; et al. Plant trait responses to grazing–a global synthesis. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2007, 13, 313–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, C.S.; Beck, J.L.; Tanaka, J.A. Livestock grazing and sage-grouse habitat: Impacts and opportunities. J. Rangel. Appl. 2014, 1, 58–77. [Google Scholar]

- Krausman, P.R.; Naugle, D.E.; Frisina, M.R.; Northrup, R.; Bleich, V.C.; Block, W.M.; Wallace, M.C.; Wright, J.D. Livestock grazing, wildlife habitat, and rangeland values. Rangelands 2009, 31, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A. Effects of cattle grazing on North American arid ecosystems: A quantitative review. West. N. Am. Nat. 2000, 60, 155–164. [Google Scholar]

- George, M.R.; Jackson, R.D.; Boyd, C.S.; Tate, K.W. A Scientific Assessment of the Effectiveness of Riparian Management Practices. In Conservation Benefits of Rangeland Practices: Assessment, Recommendations, and Knowledge Gaps; Briske, D.D., Ed.; USDA-NRCS: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; pp. 213–252. [Google Scholar]

- Sliwinski, M.S.; Koper, N. Managing mixed-grass prairies for songbirds using variable cattle stocking rates. Rangel. Ecol. Manag. 2015, 68, 470–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malan, J.A.C.; Flint, N.; Jackson, E.L.; Irving, A.D.; Swain, D.L. Offstream watering points for cattle: Protecting riparian ecosystems and improving water quality? Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2018, 256, 44–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Callaghan, P.; Kelly-Quinn, M.; Jennings, E.; Antunes, P.; O’Sullivan, M.; Fenton, O.; Huallachain, D.O. The environmental impact of cattle access to watercourses: A review. J. Environ. Qual. 2019, 48, 340–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derose, K.L.; Roche, L.M.; Lile, D.F.; Eastburn, D.J.; Tate, K.W. Microbial Water Quality Conditions Associated with Livestock Grazing, Recreation, and Rural Residences in Mixed-Use Landscapes. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holechek, J.L.; Gomez, H.; Molinar, F.; Galt, D. Grazing studies: What we’ve learned. Rangel. Arch. 1999, 21, 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Luoto, M.; Pykälä, J.; Kuussaari, M. Decline of landscape-scale habitat and species diversity after the end of cattle grazing. J. Nat. Conserv. 2003, 11, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, D.R.; Marty, J.; Holland, R.F. Whither the rangeland?: Protection and conversion in California’s rangeland ecosystems. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e103468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, A.K.; Blair, J.M.; Briggs, J.M.; Collins, S.L.; Hartnett, D.C.; Johnson, L.C.; Towne, E.G. The keystone role of bison in North American tallgrass prairie: Bison increase habitat heterogeneity and alter a broad array of plant, community, and ecosystem processes. BioScience 1999, 49, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.M.; Goble, D.D.; Wiens, J.A.; Wilcove, D.S.; Bean, M.; Male, T. Recovery of imperiled species under the Endangered Species Act: The need for a new approach. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2005, 3, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohlf, D.J.; Carroll, C.; Hartl, B. Conservation-Reliant Species: Toward a Biology-Based Definition. BioScience 2014, 64, 601–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.M.; Goble, D.D.; Haines, A.M.; Wiens, J.A.; Neel, M.C. Conservation-reliant species and the future of conservation. Conserv. Lett. 2010, 3, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, T.M.; Bellard, C.; Ricciardi, A. Alien versus native species as drivers of recent extinctions. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2019, 17, 203–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavaleta, E.S.; Hobbs, R.J.; Mooney, H.A. Viewing invasive species removal in a whole-ecosystem context. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2001, 16, 454–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kettenring, K.M.; Adams, C.R. Lessons learned from invasive plant control experiments: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Appl. Ecol. 2011, 48, 970–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’antonio, C.M.; Vitousek, P.M. Biological invasions by exotic grasses, the grass/fire cycle, and global change. Ann. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1992, 23, 63–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapero, M.W.K.; Huntsinger, L.; Becchetti, T.A.; Mashiri, F.E.; James, J.J. Land manager perceptions of opportunities and constraints of using livestock to manage invasive plants. Rangel. Ecol. Manag. 2018, 71, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, J.D.; Chen, X.D.; Johnson, C.S. Effects of herbicides on Behr’s metalmark butterfly, a surrogate species for the endangered butterfly, Lange’s metalmark. Environ. Pollut. 2012, 164, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germano, D.J.; Rathbun, G.B.; Saslaw, L.R.; Cypher, B.L.; Cypher, E.A.; Vredenburgh, L.M. The San Joaquin Desert of California: Ecologically misunderstood and overlooked. Nat. Areas J. 2011, 31, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minnich, R.A. California’s Fading Wildflowers: Lost Legacy and Biological Invasions; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Z.Y.; Jiao, F.; Li, Y.H.; Kallenbach, R.L. Anthropogenic disturbances are key to maintaining the biodiversity of grasslands. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loeser, M.R.; Sisk, T.D.; Crews, T.E. Impact of grazing intensity during drought in an Arizona grassland. Conserv. Biol. 2007, 21, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rook, A.J.; Dumont, B.; Isselstein, J.; Osoro, K.; WallisDeVries, M.F.; Parente, G.; Mills, J. Matching type of livestock to desired biodiversity outcomes in pastures—A review. Biol. Conserv. 2004, 119, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuhlendorf, S.D.; Engle, D.M. Restoring heterogeneity on rangelands: Ecosystem management based on evolutionary grazing patterns. BioScience 2001, 51, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noy-Meir, I. Interactive effects of fire and grazing on structure and diversity of Mediterranean grasslands. J. Veg. Sci. 1995, 6, 701–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holechek, J.L.; Baker, T.T.; Boren, J.C.; Galt, D. Grazing impacts on rangeland vegetation: What we have learned. Rangelands 2006, 28, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, K.E.; Fowler, M.S.; Skov, M.W.; Doerr, S.H.; Beaumont, N.; Griffin, J.N. Livestock grazing alters multiple ecosystem properties and services in salt marshes: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Ecol. 2017, 54, 1395–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaplin-Kramer, R.; George, M.R. Effects of climate change on range forage production in the San Francisco Bay Area. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e57723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenn, M.E.; Allen, E.B.; Weiss, S.B.; Jovan, S.; Geiser, L.H.; Tonnesen, G.S.; Johnson, R.F.; Rao, L.E.; Gimeno, B.S.; Yuan, F.; et al. Nitrogen critical loads and management alternatives for N-impacted ecosystems in California. J. Environ. Manag. 2010, 91, 2404–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunt, I.D.; Eldridge, D.J.; Morgan, J.W.; Witt, G.B. A framework to predict the effects of livestock grazing and grazing exclusion on conservation values in natural ecosystems in Australia. Aust. J. Bot. 2007, 55, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, C.; Rohlf, D.J.; Li, Y.W.; Hartl, B.; Phillips, M.K.; Noss, R.F. Connectivity conservation and endangered species recovery: A study in the challenges of defining conservation-reliant species. Conserv. Lett. 2015, 8, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Categories for Grazing’s Mention | Impact Statements or Category Descriptions |

| Livestock grazing current |

|

| No longer a factor |

|

| No current threat |

|

| Other grazing threatens |

|

| Island species |

|

| Categories of grazing’s current threats | |

| Grazing or overgrazing threatens |

|

| Unknown grazing threat |

|

| No grazing threat |

|

| Categories of grazing’s current benefit | |

| Grazing benefits |

|

| Unknown grazing benefit |

|

| No grazing benefit |

|

| Livestock Grazing Mentions | # of Animal Species | % of Listed Species | # of Plant Species | % of Listed Species | Total | % of Listed Species | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Other grazers (feral, wild) | 1 | 7 | 8 | 3% | ||||

| Island species (historic, feral) | 3 | 21 | 24 | 9% | ||||

| No Longer (historic) | 2 | 17 | 13 | 5% | ||||

| No Current | 6 | 9 | 14 | 5% | ||||

| Livestock grazing current | 56 | 56% | 87 | 48% | 143 | 51% | ||

| Total grazing mentions | 68 | 68% | 141 | 78% | 209 | 74% | ||

| Total listed species | 100 | 182 | 282 | |||||

| Livestock Grazing Current (Threats and Benefits) | # of Animal Species n = 56 | % of Current Animals | # of Plant Species n = 87 | % of Current Plants | Total | % of Listed Species |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grazing threat | 47 | 84% | 57 | 66% | 104 | 37% |

| Unknown grazing threat | 2 | 4% | 5 | 6% | 7 | 2% |

| No grazing threat | 7 | 13% | 25 | 29% | 32 | 11% |

| Grazing benefit | 36 | 64% | 49 | 56% | 85 | 30% |

| Unknown grazing benefit | 0 | 4 | 5% | 4 | 1% | |

| No grazing benefit | 20 | 36% | 34 | 39% | 54 | 19% |

| Both grazing threat and benefit | 30 | 53% | 35 | 40% | 65 | 23% |

| Threat | Benefit | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difference in Grazing’s Role for Each | n | Pearson’s X2 | df | p-Value | Pearson’s X2 | df | p-Value | ||

| Animals vs. plants | 143 | 5.931 | 2 | 0.05 | * | 3.04 | 2 | 0.22 | |

| Animal species group | 56 | 10.385 | 12 | 0.58 | 17.07 | 6 | 0.01 | ** | |

| Plant guild | 87 | 10.001 | 10 | 0.44 | 17.396 | 10 | 0.07 | ||

| Terrestrial habitat | 105 | 25.835 | 16 | 0.06 | 29.161 | 16 | 0.02 | * | |

| Aquatic habitat | 73 | 20.126 | 12 | 0.07 | 18.473 | 12 | 0.10 | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barry, S.; Huntsinger, L. Rangeland Land-Sharing, Livestock Grazing’s Role in the Conservation of Imperiled Species. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4466. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084466

Barry S, Huntsinger L. Rangeland Land-Sharing, Livestock Grazing’s Role in the Conservation of Imperiled Species. Sustainability. 2021; 13(8):4466. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084466

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarry, Sheila, and Lynn Huntsinger. 2021. "Rangeland Land-Sharing, Livestock Grazing’s Role in the Conservation of Imperiled Species" Sustainability 13, no. 8: 4466. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084466

APA StyleBarry, S., & Huntsinger, L. (2021). Rangeland Land-Sharing, Livestock Grazing’s Role in the Conservation of Imperiled Species. Sustainability, 13(8), 4466. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084466