Human Dimensions of Urban Blue and Green Infrastructure during a Pandemic. Case Study of Moscow (Russia) and Perth (Australia)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

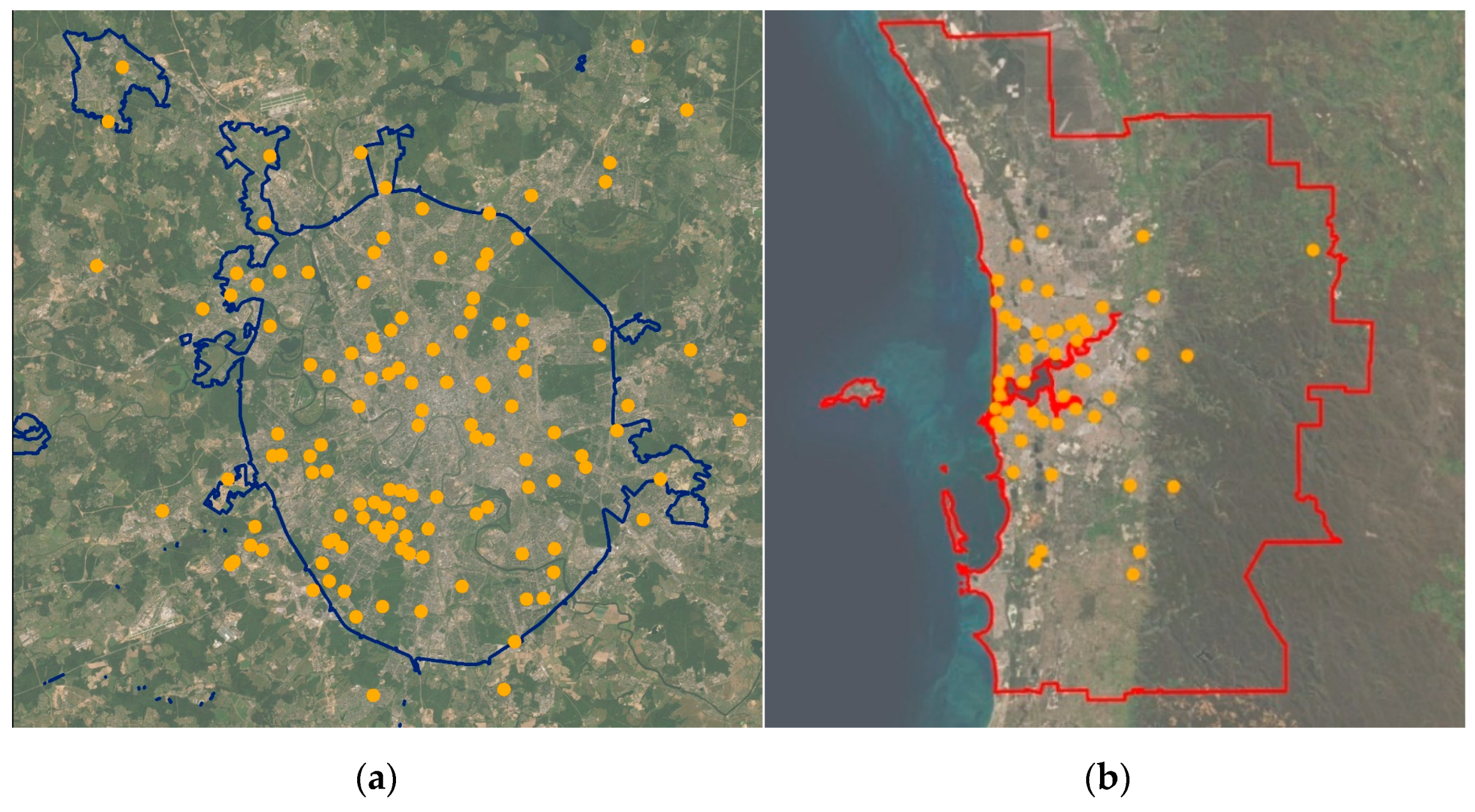

2.1. Study Sites

2.1.1. Perth

2.1.2. Moscow

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Questionnaire Design

- information on the area of residence (for geographical identification to confirm the respondent was in the metropolitan sample area, the extent/provision of urban BGI in the area, and how long each area was under lockdown);

- subjective values assigned to urban green and blue spaces;

- perceived personal impacts of COVID-19 related restrictions;

- self-reported impacts of COVID-19 restrictions on access to urban green and blue spaces;

- subjective assessment of urban green and blue spaces adequacy and quality in the respondents’ local neighborhood;

- general demographic information.

2.4. Survey Distribution

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Chronicle of COVID-19 Pandemic and Analysis of Its Impact

3.2. Social Survey Results

3.2.1. Description of Samples

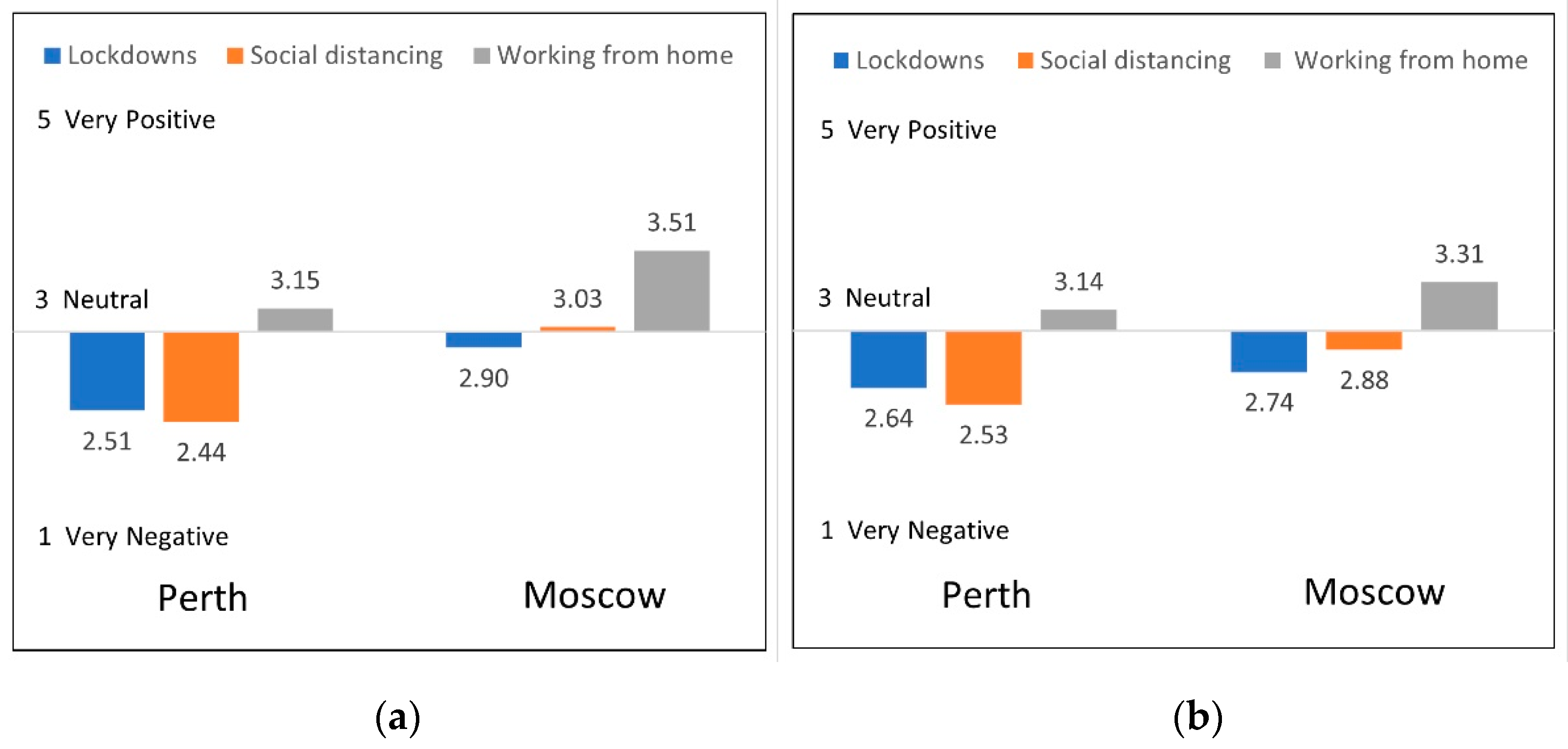

3.2.2. The Main Challenges of COVID-19 Restrictions

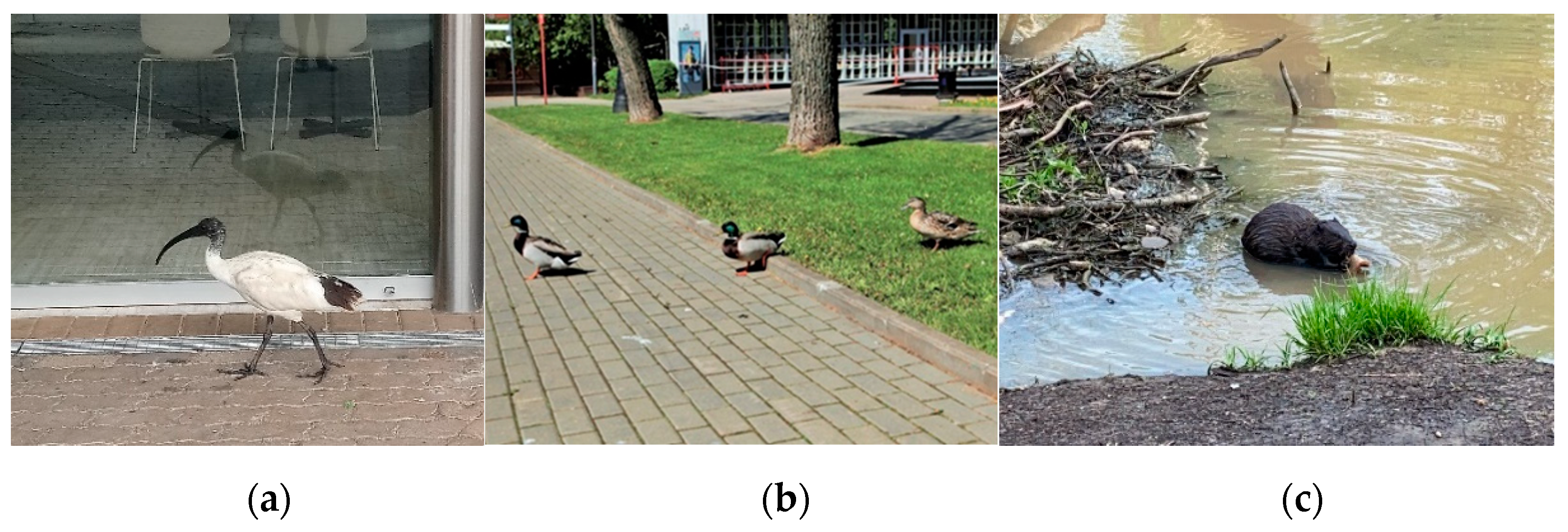

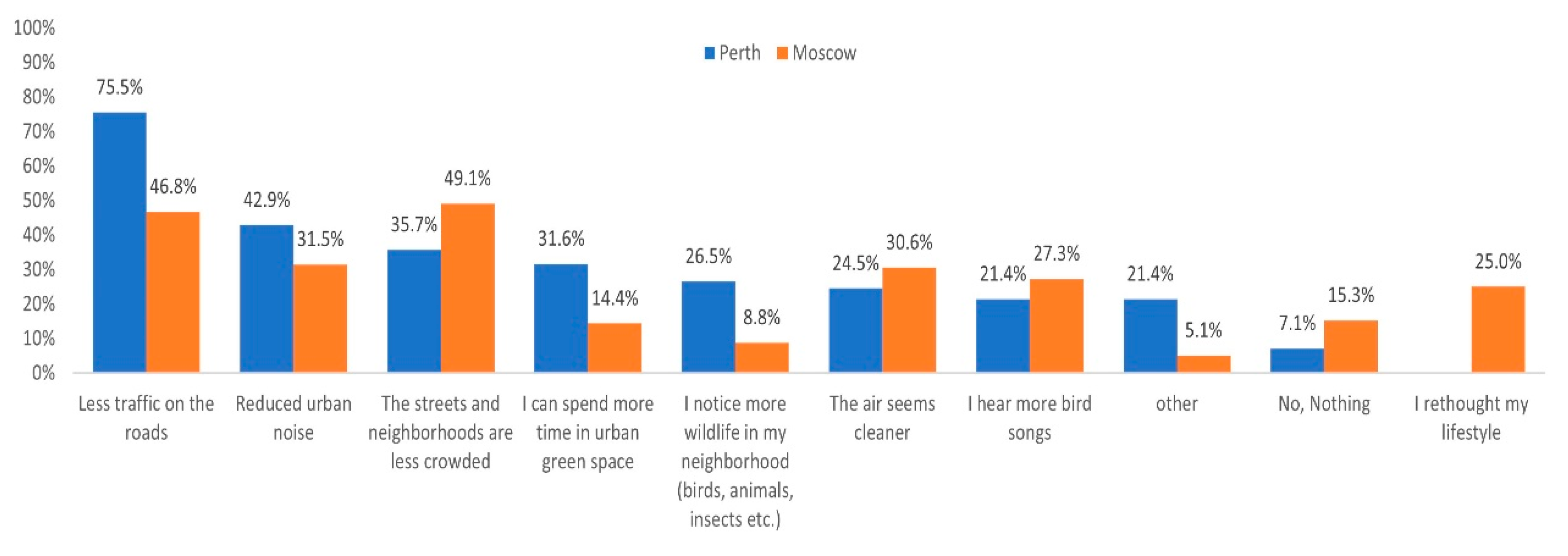

3.2.3. Perceived Benefits of COVID Restrictions

3.2.4. Activities to Cope with COVID Restrictions

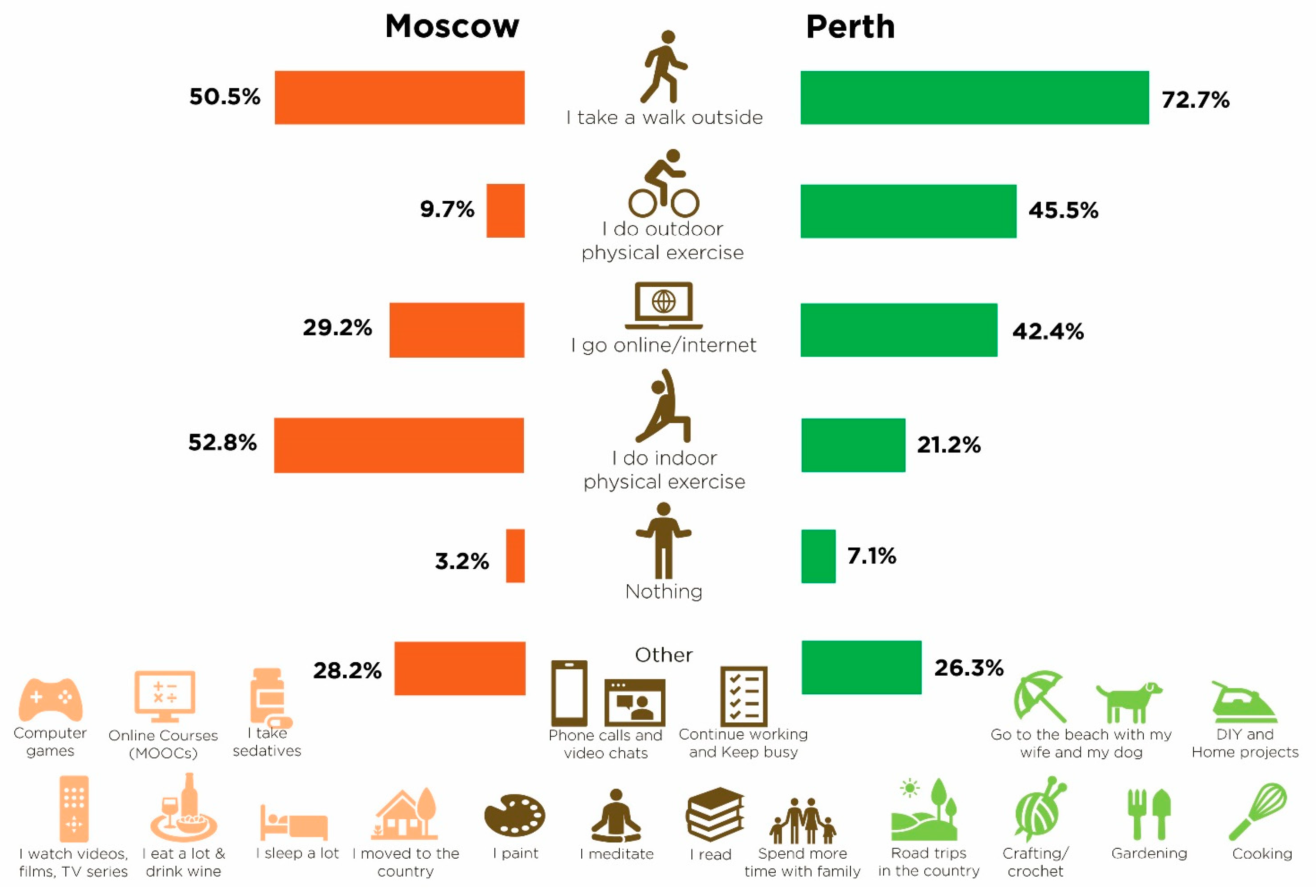

3.2.5. Importance of Contact with Nature for Physical and Mental Well-Being

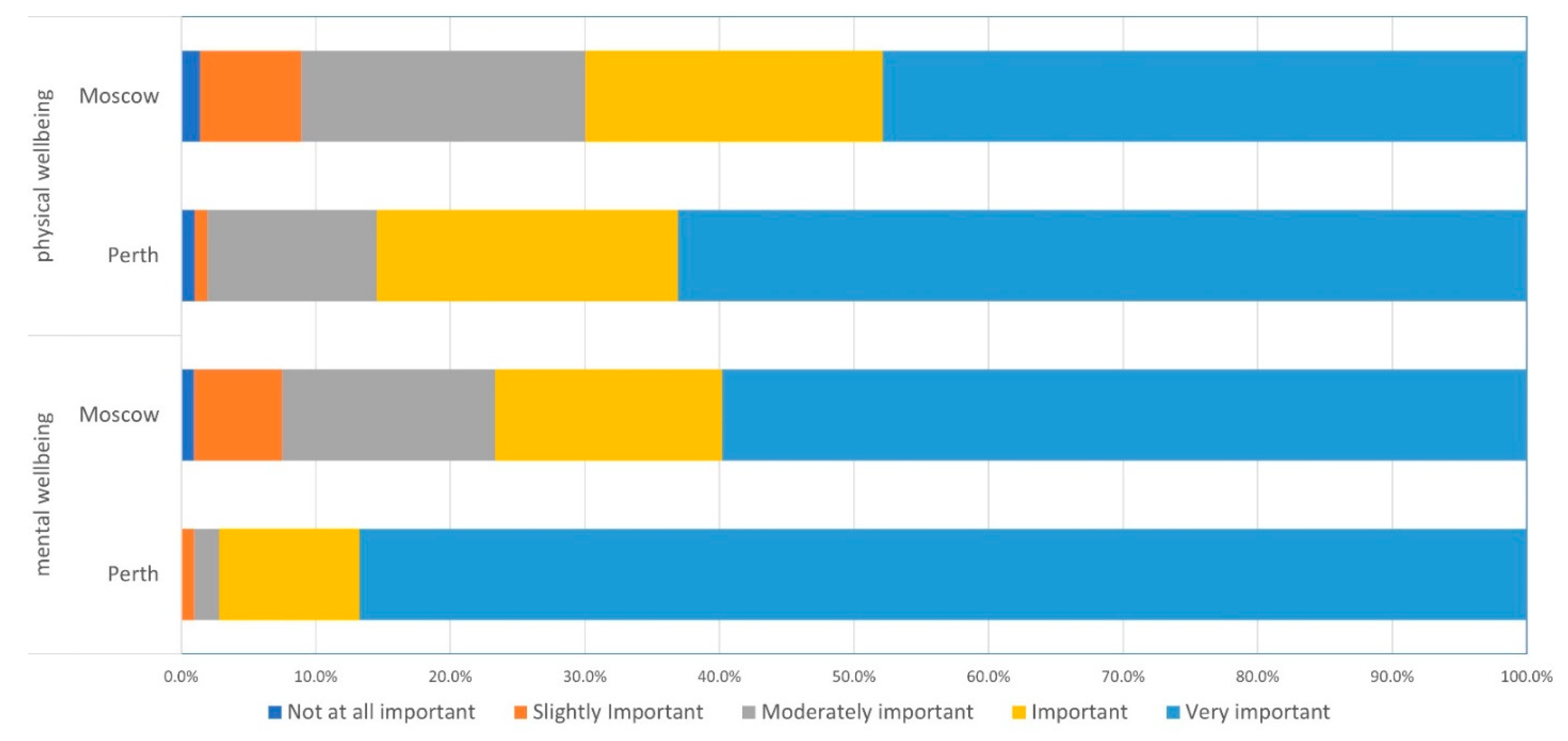

3.2.6. Perceived Personal Benefits of UGS

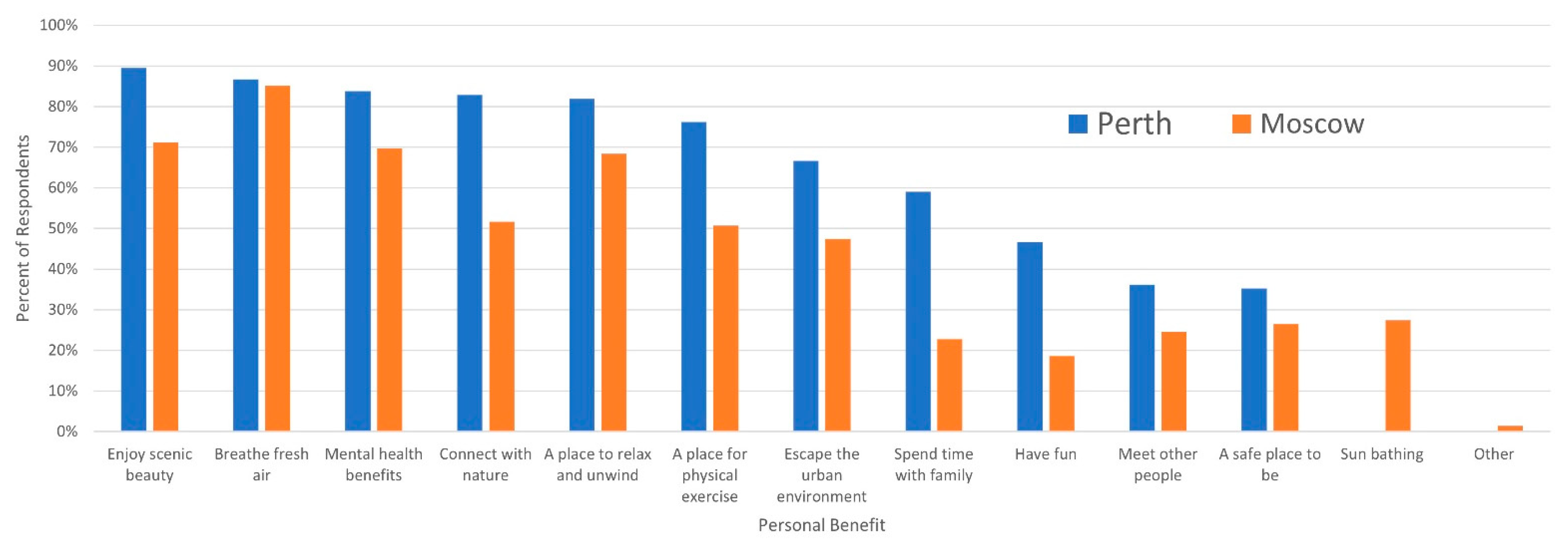

3.2.7. Changes in Urban Green and Blue Spaces Visitation

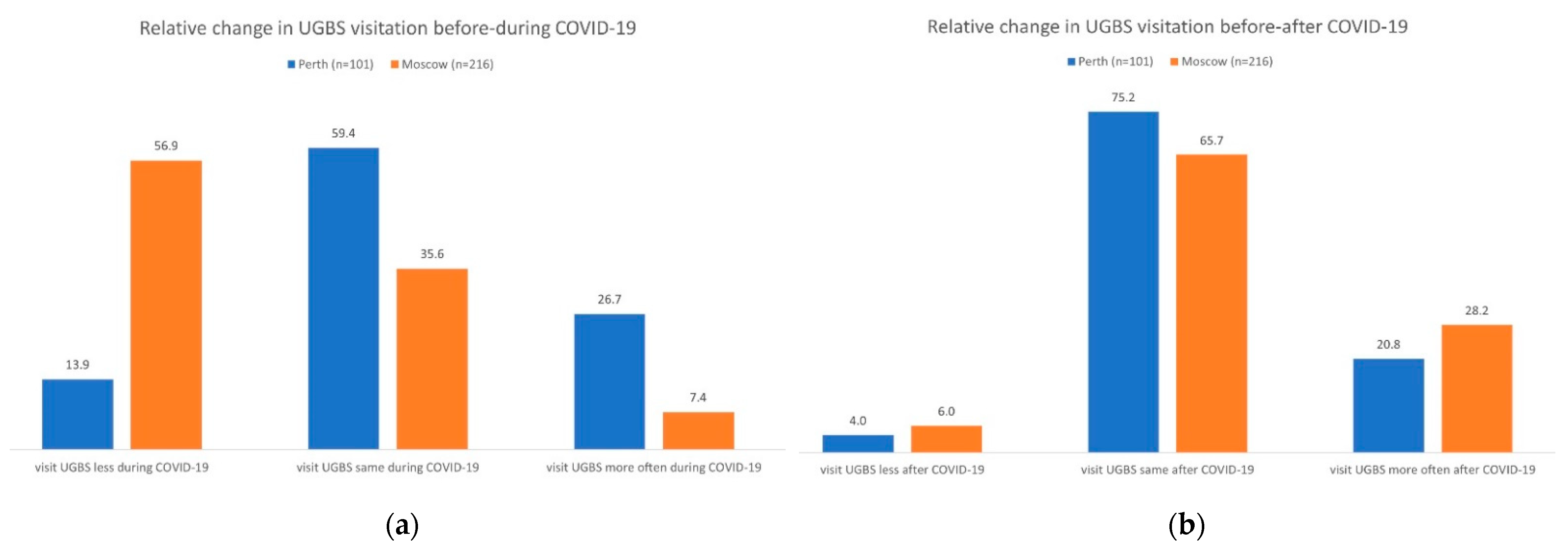

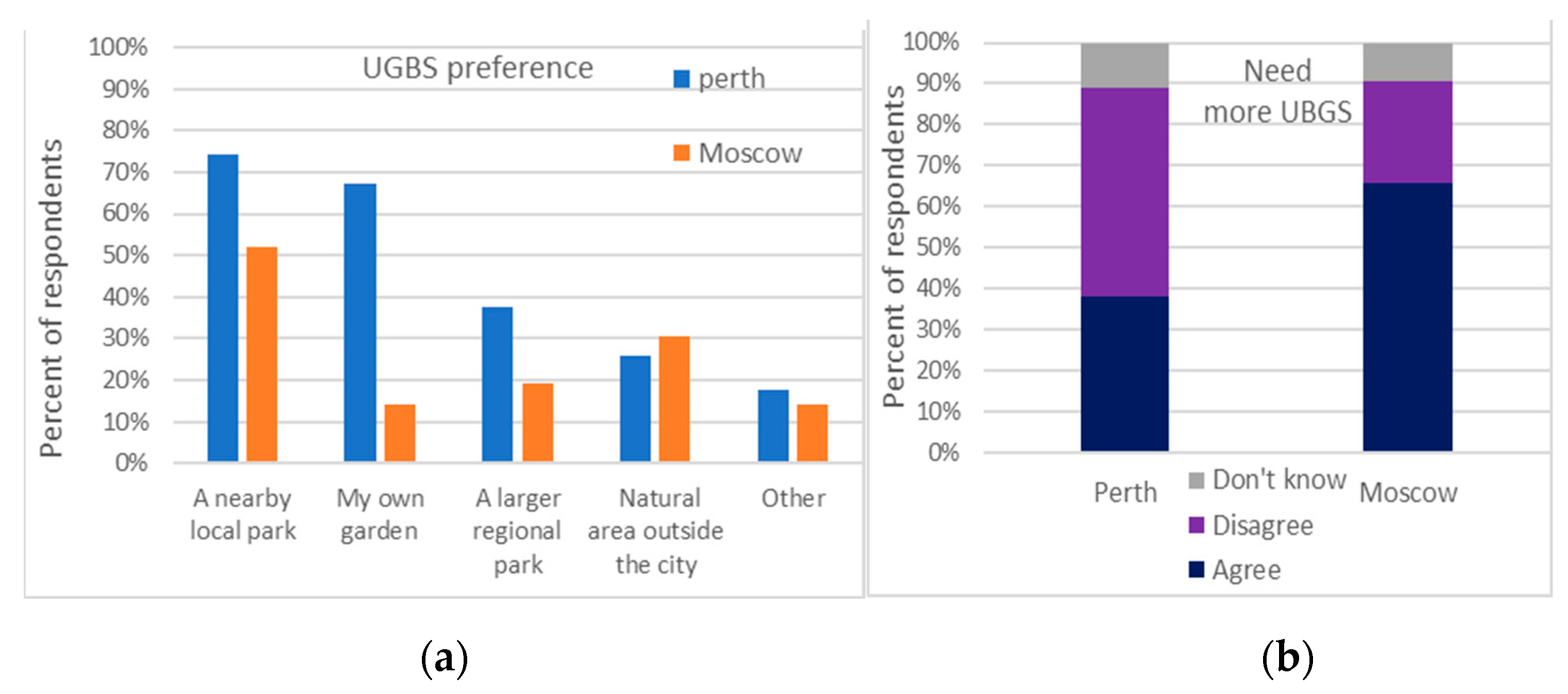

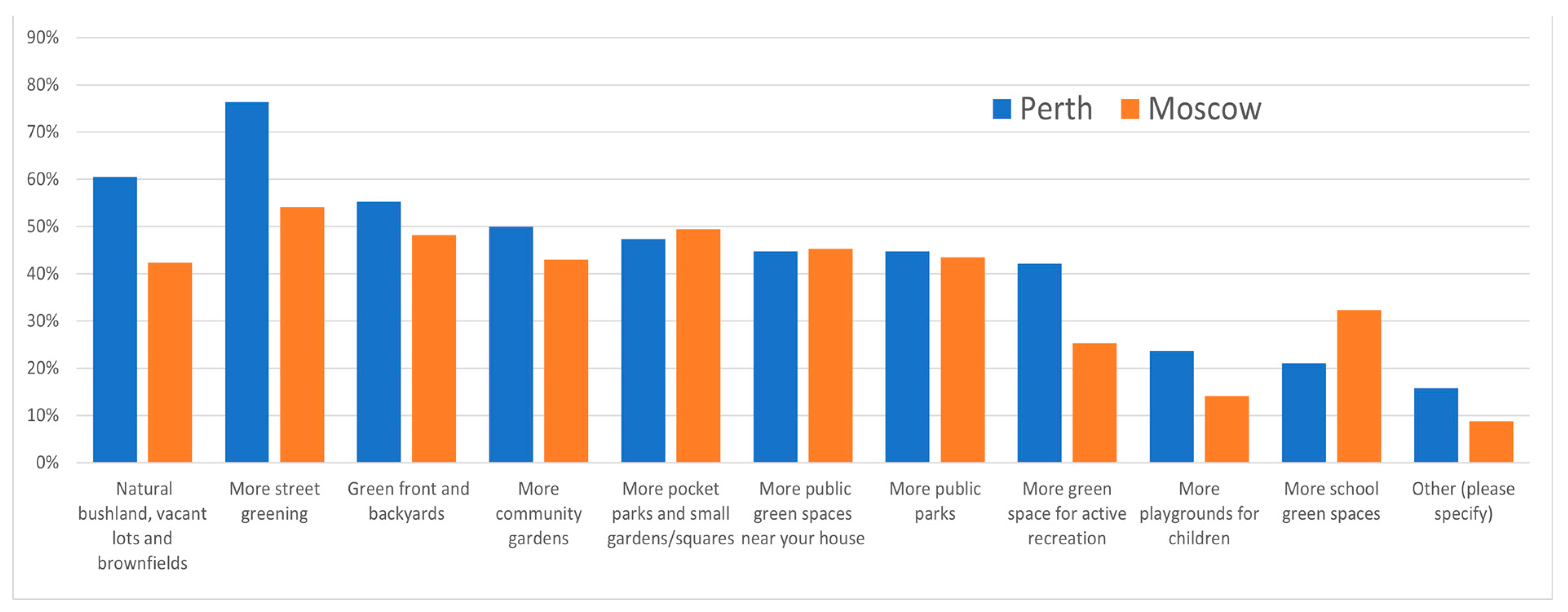

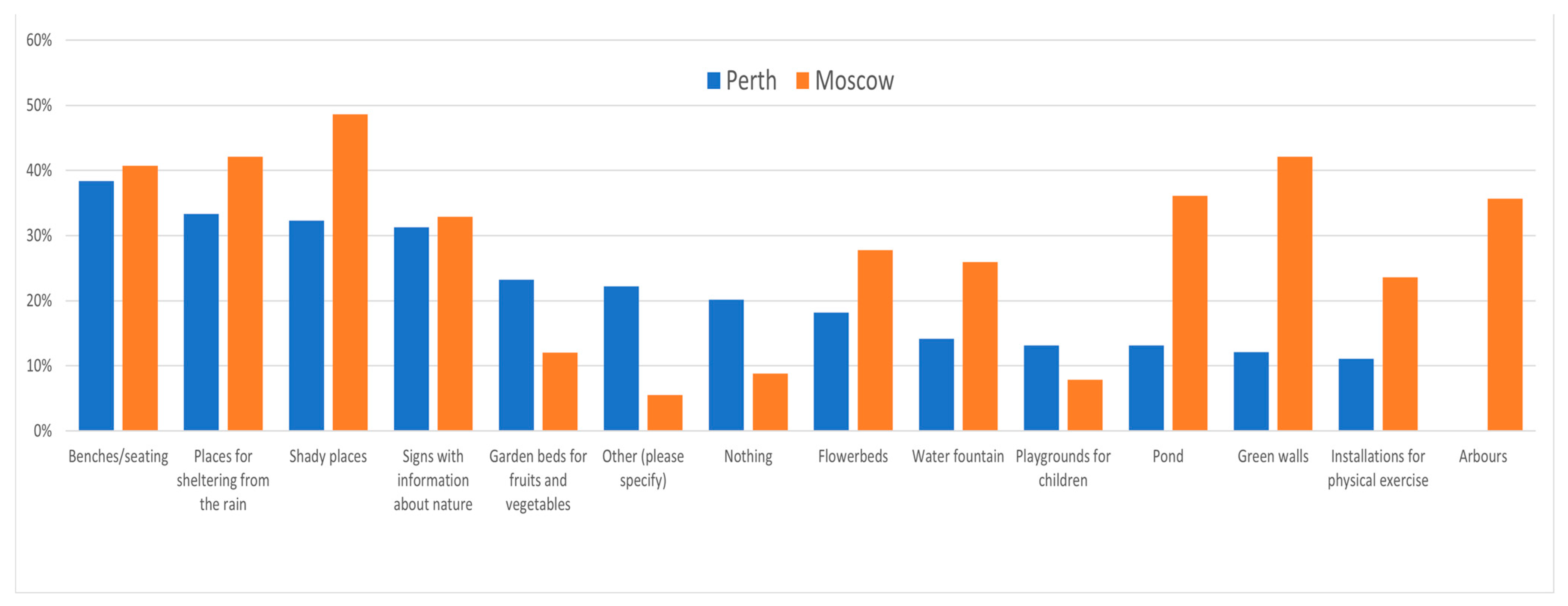

3.2.8. Urban Green and Blue Spaces Access Preferences and Demand

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xie, J.; Luo, S.; Furuya, K.; Sun, D. Urban Parks as Green Buers During the-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugolini, F.; Massetti, L.; Calaza-Martinez, P.; Cariñanos, P.; Dobbs, C.; Ostoic, S.K.; Marin, A.M.; Pearlmutter, D.; Saaroni, H.; Šaulienė, I.; et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the use and perceptions of urban green space: An international exploratory study. Urban For. Urban Green 2020, 56, 126888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouso, S.; Borja, A.; Fleming, L.E.; Gómez-Baggethun, E.; White, M.P.; Uyarra, M.C. Contact with blue-green spaces during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown beneficial for mental health. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, S.J.; Christiana, R.W.; Gustat, J. Recommendations for Keeping Parks and Green Space Accessible for Mental and Physical Health During COVID-19 and Other Pandemics. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2020, 17, 200204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghofrani, Z.; Sposito, V.; Faggian, R. A comprehensive review of blue-green infrastructure concepts. Environ. Sustain. 2017, 6, 15–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dushkova, D.; Ignatieva, M.; Melnichuk, I. Urban Greening as a Response to Societal Challenges. Towards Biophilic Megacities (Case Studies of Saint Petersburg and Moscow, Russia). In Making Green Cities: Concepts, Challenges and Practice; Breuste, J., Artmann, M., Ioja, C., Qureshi, S., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, M. Researching the links between parklands and health. In Wellness Tourism: A Destination Perspective; Voigt, C., Pforr, C., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 147–160. [Google Scholar]

- Ignatieva, M.; Haase, D.; Dushkova, D.; Haase, A. Lawns in Cities: From a Globalised Urban Green space phenomenon to Sustainable Nature-Based Solutions. Land 2020, 9, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, E.; Langemeyer, J.; Borgström, S.; McPhearson, T.; Haase, D.; Kronenberg, J.; Barton, D.N.; Davis, M.; Naumann, S.; Röschel, N.L.; et al. Enabling Green and Blue Infrastructure to Improve Contributions to Human Well-Being and Equity in Urban Systems. BioScience 2019, 69, 566–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreucci, A.B.; Russo, A.; Olszewska-Guizzo, A. Designing Urban Green Blue Infrastructure for Mental Health and Elderly Wellbeing. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grima, N.; Corcoran, W.; Hill-James, C.; Langton, B.; Sommer, H.; Fisher, B. The importance of urban natural areas and urban ecosystem services during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0243344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braubach, M.; Egorov, A.; Mudu, P.; Wolf, T.; Ward Thompson, C.; Martuzzi, M. Effects of Urban Green Space on Environmental Health, Equity and Resilience. In Nature-Based Solutions to Climate Change Adaptation in Urban Areas. Theory and Practice of Urban Sustainability Transitions; Kabisch, N., Korn, H., Stadler, J., Bonn, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabisch, N.; Haase, D. Urban nature benefits—Opportunities for improvement of health and well-being in times of global change. Who Newsl Hous. Health 2018, 29, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Völker, S.; Kistemann, T. The impact of blue space on human health and well-being—Salutogenetic health effects of inland surface waters: A review. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2011, 214, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamond, J.; Everett, G. Sustainable Blue-Green Infrastructure: A social practice approach to understanding community preferences and stewardship. Landsc. Urban Plan 2019, 191, 103639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Q.; Wang, L.; Guo, Q.; Li, Y.; Liu, M.; Xu, G. Evaluating Cultural Ecosystem Services of Urban Residential Green Spaces From the Perspective of Residents’ Satisfaction With Green Space. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ode Sang, Å.; Knez, I.; Gunnarsson, B.; Hedblom, M. The effects of naturalness, gender, and age on how urban green space is perceived and used. Urban For. Urban Green. 2016, 18, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, D.; Haase, D.; Mascarenhas, A.; Langemeyer, J.; Baro, F.; Kennedy, C.P.; Andersson, E.; McPhearson, T. Enabling Access to Greenspace during the Covid-19 Pandemic—Perspectives from Five Cities. Nat. Cities. 2020. Available online: https://www.thenatureofcities.com/2020/05/04/enabling-access-to-greenspace-during-the-covid-19-pandemic-perspectives-from-five-cities/ (accessed on 15 June 2020).

- Finnsson, P.T. COVID19 Crisis Highlights the Need for Accessible and Productive Urban Green Spaces. Nordregio Magazine 2020. Issue “Postpandemic Regional Development”. 2020. Available online: https://nordregio.org/nordregio-magazine/issues/post-pandemic-regional-development/covid19-crisis-highlights-the-need-for-accessible-and-productive-urban-green-spaces/ (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Uchiyama, Y.; Kohsaka, R. Access and Use of Green Areas during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Green Infrastructure Management in the “New Normal”. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinschroth, F.; Kowarik, I. COVID-19 crisis demonstrates the urgent need for urban greenspaces. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2020, 18, 318–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, S.; Deschacht, N. Public Awareness of Nature and the Environment During the COVID-19 Crisis. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2020, 76, 1149–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoari, N.; Ezzati, M.; Baumgartner, J.; Malacarne, D.; Fecht, D. Accessibility and allocation of public parks and gardens in England and Wales: A COVID-19 social distancing perspective. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0241102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennon, M. Green space and the compact city: Planning issues for a “new normal”. Cities Health 2020, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordshakeri, P.; Fazeli, E. How the COVID-19 pandemic highlights the lack of accessible public spaces in Tehran. Cities Health 2020, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, Z.S.; Barton, D.N.; Gundersen, V.; Figari, H. Urban nature in a time of crisis: Recreational use of green space increases during the COVID-19 outbreak in Oslo, Norway. SocArXiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennewell, C.; Shaw, B.J. Perth, Western Australia. Cities 2008, 25, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.; Newsome, D. Perth (Australia) as one of the world’s most liveable cities: A perspective on society, sustainability and environment. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2015, 1, 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, N.; Mittermeier, R.A.; Mittermeier, C.G.; da Fonseca, G.A.B.; Kent, J. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 2000, 403, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crilley, G.; Weber, D.; Taplin, R. Predicting visitor satisfaction in parks: Comparing the value of personal benefit attainment and service levels in Kakadu National Park, Australia. Visit. Stud. 2012, 15, 217–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyle, B.D.; Weiler, B. Revisiting the importance of visitation: Public perceptions of park benefits. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2017, 17, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madureira, H.; Nunes, F.; Oliveira, J.; Madureira, T. Preferences for urban green space characteristics: A comparative study in three Portuguese cities. Environments 2018, 5, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Van den Berg, A.E.; VanDijk, T.; Weitkamp, G. Quality over quantity: Contribution of urban green space to neighborhood satisfaction. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobyanin Explained the Rules of Walking and Outdoor Sports; RIA Novosti. 27 May 2020. Available online: https://ria.ru/20200527/1572086956.html?utm_source=yxnews&utm_medium=desktop&utm_referrer=https%3A%2F%2Fyandex.ru%2Fnews (accessed on 12 November 2020). (In Russian).

- Coronavirus Restrictions Leave Gyms Facing Tough Recovery as Fitness Industry Looks for Silver Lining. 28 May 2020. Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-05-28/gyms-hit-hard-by-coronavirus-crisis-as-fitness-industry-adapts/12293978 (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- Mental Disorders: What People Suffer after the Coronavirus. 4 August 2020. Available online: https://www.gazeta.ru/social/2020/08/04/13177285.shtml (accessed on 12 November 2020).

- WA Impact Statement: COVID-19 Pandemic. State of Western Australia 2020; Department of the Premier and Cabinet, Western Australia. Available online: https://www.wa.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-07/WA%20Impact%20Statement.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2020). (In Russian)

- Coronavirus COVID-19 Monitor. Moskalkova Reported an Increase in Cases of Domestic Violence during the Epidemic. Available online: https://coronavirus-monitor.ru/ru/novosti/moskalkova-soobshchila-o-roste-sluchaev-domashnego-nasiliya-vo-vremya-epidemii (accessed on 4 November 2020). (In Russian).

- Ministry of Transport of the Russian Federation. Transport of Russia. Information and Statistical Bulletin. January–June 2020. Available online: https://www.mintrans.gov.ru/documents/7/10880 (accessed on 17 November 2020). (In Russian)

- News. The Data Shows How the Coronavirus Shutdown Transformed Life in Australia’s Most Isolated City. Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-04-26/life-in-perth-during-a-global-coronavirus-pandemic-in-photos/12174454 (accessed on 25 November 2020).

- TASS. Mosekomonitoring Has Recorded a Decrease in Air Pollution in the Capital [Moscow]. Available online: https://tass.ru/moskva/9115199 (accessed on 17 November 2020). (In Russian).

- Australia’s Science Channel. These 5 Images Show How Air Pollution Changed over Australia’s Major Cities before and after Lockdown. Available online: https://australiascience.tv/air-pollution-over-australian-cities-during-lockdown/ (accessed on 29 November 2020).

- COVID-19 Mobility: Find out How People Move around the City in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Available online: https://www.google.com/covid19/mobility/?hl=ru (accessed on 3 December 2020). (In Russian).

- ICLEI. Australians More Positive about Public Green Spaces. Available online: https://www.icleioceania.org/icleioceanianews/2020/8/12/covid-19-green-space#:~:text=In%20April%202020%2C%20Greener%20Spaces,community%20attitudes%20towards%20green%20space (accessed on 20 December 2020).

- Buckley, S. Green Spaces Help Soothe COVID-19 Restrictions. Available online: https://www.architectureanddesign.com.au/news/a-greener-covid-19# (accessed on 18 March 2021).

- Sharifi, A.; Khavarian-Garmsir, A.R. The COVID-19 pandemic: Impacts on cities and major lessons for urban planning, design, and management. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 749, 142391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kronenberg, J.; Haase, A.; Laszkiewicz, E.; Antal, A.; Baravikova, A.; Dushkova, D.; Filčak, R.; Haase, D.; Ignatieva, M.; Khmara, Y.; et al. Environmental justice in the context of urban green space availability, accessibility, and attractiveness in postsocialist cities. Cities 2020, 106, 102862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadpoor, N.; Shahab, S. Urban form: Realising the value of green space: A planners’ perspective on the COVID-19 pandemic. Town Plan Rev 2021, 92, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Health England. Improving Access to Greenspace: A New Review for 2020; PHE Publications: London, UK, 2020; Available online: https://beyondgreenspace.net/2020/07/29/improving-access-to-greenspace-a-new-review-for-2020/ (accessed on 8 January 2021).

- Lopez, B.; Kennedy, C.; McPhearson, T. Parks are Critical Urban Infrastructure: Perception and Use of Urban Green Spaces in NYC During COVID-19. Preprints 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honey-Roses, J.; Anguelovski, I.; Bohigas, J.; Chireh, V.K.; Daher, C.; van den Bosch, C.K.; Litt, J.; Mawani, V.; McCall, M.K.; Orellana, A.; et al. The Impact of COVID-19 on Public Space: A Review of the Emerging Questions. Preprints 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, M.D.; Luís, N.C. COVID-19 Could Leverage a Sustainable Built Environment. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanzl, M. Urban forms and green infrastructure—The implications for public health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cities Health 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otu, A.; Charles, C.H.; Yaya, S. Mental health and psychosocial well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: The invisible elephant in the room. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2020, 14, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soga, M.; Evans, M.J.; Tsuchiya, K.; Fukano, Y. A room with a green view: The importance of nearby nature for mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ecol. Appl. 2020, 31, e2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takieddine, H.; AL Tabbah, S. Coronavirus Pandemic: Coping with the Psychological Outcomes, Mental Changes, and the “New Normal” During and After COVID-19. Open J. Depress. Anxiety 2020, 2, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuelsson, K.; Barthel, S.; Colding, J.; Macassa, G.; Giusti, M. Urban nature as a source of resilience during social distancing amidst the coronavirus pandemic. Landsc. Urban Plan 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cave, B.; Kim, J.; Viliani, F.; Harris, P. Applying an equity lens to urban policy measures for COVID-19 in four cities. Cities Health 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geary, R.S.; Wheeler, B. A call to action: Improving urban green spaces to reduce health inequalities exacerbated by COVID-19. Prev. Med. 2021, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, K.; Van Ham, C.; Andersson, E. Green Refuges for Enabling Cities’ Preparedness for Future Pandemics and Global Change; ENABLE Factsheet. 2020. Available online: https://oppla.eu/sites/default/files/images/ENABLE_factsheet_Green_spaces_as_pandemic_refuges.pdf?pk_campaign=Outline (accessed on 1 February 2021).

| Type of BGI | Perth | Moscow |

|---|---|---|

| Public parks: Perth: bigger parks (King’s Park), local “pocket” parks in neighborhoods; Moscow: historical gardens and parks of recreation and rest (Gorky Park) |  |  |

| Green squares and boulevards in neighborhoods, greening streets in all parts of both cities |  |  |

| Greening of residential areas (front/back yards): Perth: only in private gardens and houses within the city; Moscow: public green between multistorey apartment buildings, but greening of private houses in suburbia and New Moscow |  |  |

| Nature reserve: Perth: reserved remnants of native vegetation, bushland, Moscow: forest-parks within the city boundaries |  |  |

| Rain gardens, swales, and other bioretention facilities to manage stormwater and rainwater run-off by planting native flora into depressions or channels |  |  |

| Wetlands Perth: remnants of natural wetlands and designed wetlands. Moscow: natural and designed bogs in the nature parks and in the residential districts |  |  |

| Rivers and canals as public waterways for recreational purposes |  |  |

| Ponds and creeks for recreational purposes |  |  |

| Specific blue spaces typical only for Perth (seashores) and for Moscow (artificially created water reservoirs) |  |  |

| Parameter | Moscow | Perth |

|---|---|---|

| Reduced physical activity | Due to several restrictions (The Mayor of Moscow allowed outdoor sports activities only until 9 p.m. and walking within 2 km distance from home only three times a week without sitting on the benches), physical activities were reduced [34] | Some Perth people may have shifted to physical activity indoors given a reported spike in purchasing gym equipment and online fitness training [35] |

| Negative influence on mental health | More than half of people who have had a severe form of coronavirus subsequently experience depression, insomnia, panic attacks, and other generalized mental disorders defined as post-COVID syndrome. COVID-19 strongly affects people’s daily emotional lives, increasing stress levels due to the lockdown period lengthens the fear of getting sick, or financial difficulties, especially by families with children. Online or phone calls to psychotherapists and psychologists were perceived as not real supportive measures due to the absence of physical contacts [36] | It has been reported that calls to mental health helplines, such as the Beyond Blue COVID-19 line, increased. Social isolation and anxiety associated with the public health response had a major impact on vulnerable cohorts (particularly seniors and people with disabilities, and their careers) and compounded mental health issues [37] |

| Domestic violence | The number of victims of violence and cases of domestic violence has increased by 2.5 times since April 10 and during the whole pandemic [38] | Increases in family violence incidents of around 5% between March and May 2020 compared to the same time in 2019 [37] |

| Reduced traffic | Passenger use of public transport in May–June 2020 was reduced to 54.5% of that in January–March 2020 [39] | A 79% drop in public transport use in Perth, road traffic had dropped 47%, walking journeys were down 37% (end of April) [40] |

| Reduced air pollution | For carbon monoxide, experts recorded a decrease of 11%, and for sulfur dioxide by 30% [41] | Almost no change in nitrogen dioxide emission [42] |

| Green space visits | −6% (17 May 2020)—Russia +51% (19 June 2020)—Russia +69% (10 July 2020)—Russia +41% (21 August 2020)—Moscow [43] | Increase in the appreciation and demand for open public spaces, as outlined by Greener Spaces Better Places. A total of 87% of Australian urban councils had noted a positive shift in community attitudes towards green space [44] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dushkova, D.; Ignatieva, M.; Hughes, M.; Konstantinova, A.; Vasenev, V.; Dovletyarova, E. Human Dimensions of Urban Blue and Green Infrastructure during a Pandemic. Case Study of Moscow (Russia) and Perth (Australia). Sustainability 2021, 13, 4148. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084148

Dushkova D, Ignatieva M, Hughes M, Konstantinova A, Vasenev V, Dovletyarova E. Human Dimensions of Urban Blue and Green Infrastructure during a Pandemic. Case Study of Moscow (Russia) and Perth (Australia). Sustainability. 2021; 13(8):4148. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084148

Chicago/Turabian StyleDushkova, Diana, Maria Ignatieva, Michael Hughes, Anastasia Konstantinova, Viacheslav Vasenev, and Elvira Dovletyarova. 2021. "Human Dimensions of Urban Blue and Green Infrastructure during a Pandemic. Case Study of Moscow (Russia) and Perth (Australia)" Sustainability 13, no. 8: 4148. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084148

APA StyleDushkova, D., Ignatieva, M., Hughes, M., Konstantinova, A., Vasenev, V., & Dovletyarova, E. (2021). Human Dimensions of Urban Blue and Green Infrastructure during a Pandemic. Case Study of Moscow (Russia) and Perth (Australia). Sustainability, 13(8), 4148. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084148