Parents’ Perspectives on Remote Learning in the Pandemic Context

Abstract

1. Introduction and Background

2. Research Design and Methodology

3. Results

4. Conclusions and Discussion

- (1)

- Teachers also tried to organize lessons on online communication platforms (Zoom, Skype, Microsoft Teams). In general, this trend is to be welcomed, but the availability of technologies should be taken into account as data show that in many families, devices are shared, and this means that there could be occasions when students are not able to join synchronous learning because their siblings have online lessons at that time.

- (2)

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNESCO. Education: From Disruption to Recovery. 2020. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse (accessed on 23 December 2020).

- Hodges, C.; Moore, S.; Lockee, B.; Trust, T.; Bond, A. The Difference between Emergency Remote Teaching and Online Learning. 2020. Available online: https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/3/the-difference-between-emergency-remote-teaching-and-online-learning%C2%A0%C2%A0 (accessed on 23 December 2020).

- Carlson, J.F. Context and regulation of homeschooling: Issues, evidence, and assessment practices. Sch. Psychol. 2020, 35, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, A.; Donnelly, M. New Frontiers in Research and Practice on Homeschooling. Peabody J. Educ. 2019, 94, 259–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolly, J.L.; Matthews, M.S. The shifting landscape of the homeschooling continuum. Educ. Rev. 2020, 72, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, J.; Farenga, P. Teach Your Own: The John Holt Book of Homeschooling; Da Capo Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, B.D. A systematic review of the empirical research on selected aspects of homeschooling as a school choice. J. Sch. Choice 2017, 11, 604–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- English, R. The Accidental Home Educator: A New Conceptualisation of Home Education Choice. In Global Perspectives on Home Education in the 21st Century; Rebecca English, Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, L.M. Schooling During the COVID-19 Pandemic: How Emergency Education Savings Accounts Can Meet the Needs of Every American Child; The Heritage Foundationm: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED605387.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2021).

- Henderson, L.J.; Williams, J.L.; Bradshaw, C.P. Examining home-school dissonance as a barrier to parental involvement in middle school. Prev. Sch. Fail. Altern. Educ. Child. Youth 2020, 64, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaRocque, M.; Kleiman, I.; Darling, S.M. Parental Involvement: The Missing Link in School Achievement. Prev. Sch. Fail. Altern. Educ. Child. Youth 2011, 55, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolbert, L.S.; de Ruyter, D.J.; Schinkel, A. What attitude should parents have towards their children’s future flourishing? Theory Res. Educ. 2018, 16, 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enembreck, F.; Barthès, J.A. A social approach for learning agents. Expert Syst. Appl. 2013, 40, 1902–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Cao, S.; Li, H. Young children’s online learning during COVID-19 pandemic: Chinese parents’ beliefs and attitudes. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 118, 105440, ISSN 0190-7409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amber, G.; Ogurlu, U.; Logan, N.; Cook, P. Parents’ Experiences with Remote Education during COVID-19 School Closures. Am. J. Qual. Res. 2020, 4, 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontanesi, L.; Marchetti, D.; Mazza, C.; Di Giandomenico, S.; Roma, P.; Verrocchio, M.C. The effect of the COVID-19 lockdown on parents: A call to adopt urgent measures. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2020, 12, S79–S81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubene, Z. Digital Childhood: Some Reflections from the Point of View of Philosophy of Education/Zanda Rubene. References: P.75-77//. In Innovations, Technologies and Research in Education; Daniela, L., Ed.; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2018; Chapter Six; pp. 64–77. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, H.; Shwetlena, S. The COVID-19 Pandemic: Shocks to Education and Policy Responses; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jellen, J.; Ohlbrecht, H. Parenthood in a Crisis: Stress Potentials and Gender Differences of Parents during the Corona Pandemic. Int. Dialogues Educ. 2020, 7, 44–51. [Google Scholar]

- Kesson, K.R. We are All Unschoolers Now. Middle Grades Rev. 2020, 6, 2. Available online: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/mgreview/vol6/iss1/2 (accessed on 13 January 2021).

- Bubb, S.; Jones, M.A. Learning from the COVID-19 home-schooling experience: Listening to pupils, parents/carers and teachers. Improv. Sch. 2020, 23, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, L.-A.; Vu, H.Q. Navigating ‘Home Schooling’ during COVID-19: Australian public response on Twitter. Media Int. Aust. 2021, 178, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mußél, F.; Kondratjuk, M. Home Schooling due to the Corona Pandemic: An Invitation to Think Further. Int. Dialogues Educ. 2020, 7, 28–40. [Google Scholar]

- Roshgadol, J. Quarantine Quality Time: 4 in 5 Parents Say Coronavirus Lockdown has Brought Family Closer Together. StudyFinds. 2020. Available online: https://www.studyfinds.org/quarantine-quality-time-4-in-5-parents-say-coronavirus-lockdown-has-brought-family-closer-together/ (accessed on 13 January 2021).

- Andrew, A.; Cattan, S.; Costa Dias, M.; Farquharson, C.; Kraftman, L.; Krutikova, S.; Phimister, A.; Sevilla, A. Learning during the Lockdown: Real-time Data on Children’s Experiences during Home Learning (Institute for Fiscal Studies Briefing Note No. BN288). 2020. Available online: https://www.ifs.org.uk/publications/14848 (accessed on 13 January 2021).

- Lewis, H. The Coronavirus is a Disaster for Feminism. Atlantic 2020. Available online: https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2020/03/feminism-womens-rights-coronavirus-covid19/608302/ (accessed on 14 January 2021).

- Möhring, K.; Naumann, E.; Reifenscheid, M.; Blom, A.G.; Wenz, A.; Rettig, T.; Lehrer, R.; Krieger, U.; Juhl, S.; Friedel, S.; et al. Die Mannheimer Corona-Studie: Schwerpunktbericht zu Erwerbstätigkeit und Kinderbetreuung [The Mannheim Corona Report: Focus on employment and childcare]. 2020. Available online: https://www.uni-mannheim.de/gip/corona-studie/ (accessed on 8 January 2021).

- Frey, B. The SAGE Encyclopedia of Educational Research, Measurement, and Evaluation (Vols. 1–4); SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavrakas, P.J. Encyclopedia of Survey Research Methods. In SAGE Research Methods; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; Volume 0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salkind Neil, J. Encyclopedia of Research Design. In SAGE Research Methods; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010; Volume 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniela, L.; Rūdolfa, A.; Rubene, Z. Distance education and learning platforms–Evaluation tool. In Distance Learning in Times of Pandemic: Issues, Implications and Best Practice; Taylor & Francis: Oxfordshire, UK, 2021; in press; ISBN 9780367765705. [Google Scholar]

- Pellas, N.; Kazanidis, I.; Konstantinou, N.; Georgiou, G. Exploring the educational potential of three-dimensional multi-user virtual worlds for STEM education: A mixed-method systematic literature review. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2017, 22, 2235–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullinane, C.; Montacute, R. COVID-19 and Social Mobility Impact Brief #1: School Closures. 2020. Available online: https://www.suttontrust.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/School-Shutdown-Covid-19.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2021).

- Thomas, M.S.C.; Rogers, C. Education, the science of learning, and the COVID-19 crisis. Prospects 2020, 49, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinsone, B.; Stokenberga, I. Parents’ perspective on distant learning at home during COVID-19 related restrictions. In Distance Learning in Times of Pandemic: Issues, Implications and Best Practice; Taylor & Francis: Oxfordshire, UK, 2021; in press; ISBN 9780367765705. [Google Scholar]

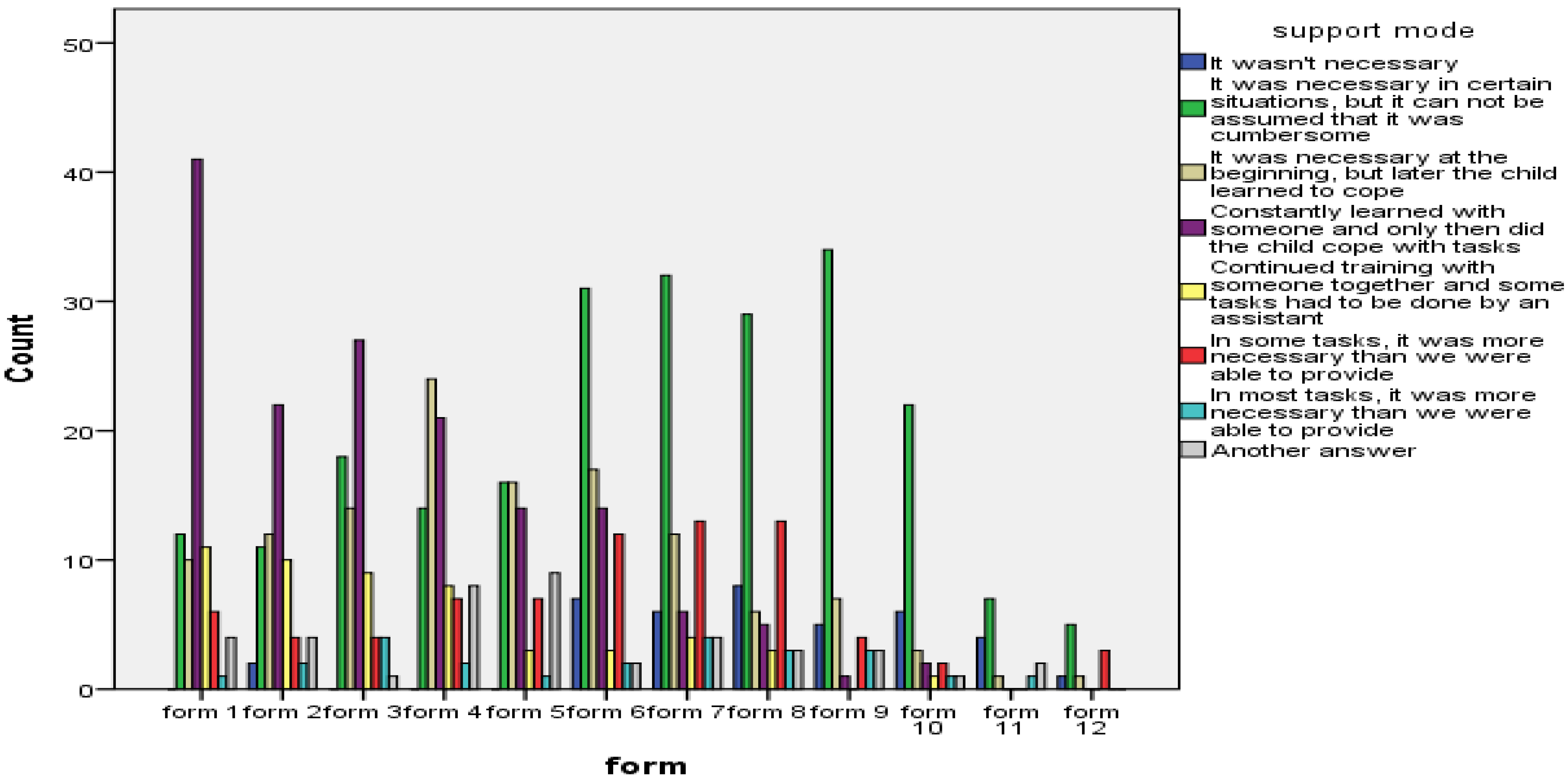

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valid | form 1 | 85 | 10.1 | 11.5 | 11.5 |

| form 2 | 67 | 8.0 | 9.1 | 20.6 | |

| form 3 | 77 | 9.2 | 10.4 | 31.0 | |

| form 4 | 84 | 10.0 | 11.4 | 42.4 | |

| form 5 | 66 | 7.9 | 8.9 | 51.4 | |

| form 6 | 88 | 10.5 | 11.9 | 63.3 | |

| form 7 | 81 | 9.7 | 11.0 | 74.3 | |

| form 8 | 70 | 8.3 | 9.5 | 83.7 | |

| form 9 | 57 | 6.8 | 7.7 | 91.5 | |

| form 10 | 38 | 4.5 | 5.1 | 96.6 | |

| form 11 | 15 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 98.6 | |

| form 12 | 10 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 738 | 88.0 | 100.0 | ||

| Missing | System | 101 | 12.0 | ||

| Total | 839 | 100.0 | |||

| Form | Online Lessons (Skype, Zoom, WhatsApp, etc.) | Sending Tasks That Had to Be Printed and Completed after Sending the Completed Work to the Teacher | Assigning tasks Using Online Learning Platforms (Uzdevumi.lv, Fizmix.lv, etc.) | Assigning Essays and Reports (Digital Submission) | Assigning Tasks from Books Where Certain Tasks Had to Be Completed (Printed Version) | Assigning creative Tasks Where the Child Needed to Do Something Independently | Physical Activities | Video Filming about the Assignment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| form 1 | Mean | 3.29 | 2.42 | 2.87 | 3.69 | 2.28 | 2.27 | 2.74 | 2.88 |

| N | 85 | 85 | 85 | 85 | 85 | 85 | 85 | 85 | |

| SD | .884 | 1.062 | .884 | .951 | 1.053 | .762 | .693 | .944 | |

| form 2 | Mean | 2.99 | 2.81 | 2.64 | 3.55 | 2.40 | 2.40 | 2.75 | 3.24 |

| N | 67 | 67 | 67 | 67 | 67 | 67 | 67 | 67 | |

| SD | .945 | 1.062 | .753 | .974 | .970 | .698 | .659 | .986 | |

| form 3 | Mean | 2.88 | 2.65 | 2.35 | 3.42 | 2.56 | 2.36 | 2.65 | 2.96 |

| N | 77 | 77 | 77 | 77 | 77 | 77 | 77 | 77 | |

| SD | .959 | 1.109 | .757 | .951 | 1.019 | .705 | .739 | .924 | |

| form 4 | Mean | 2.92 | 2.70 | 2.31 | 3.15 | 2.54 | 2.57 | 2.82 | 3.20 |

| N | 84 | 84 | 84 | 84 | 84 | 84 | 84 | 84 | |

| SD | .764 | 1.062 | .711 | 1.035 | .937 | .682 | .697 | .875 | |

| form 5 | Mean | 2.83 | 2.74 | 2.33 | 3.00 | 2.67 | 2.55 | 2.74 | 3.11 |

| N | 66 | 66 | 66 | 66 | 66 | 66 | 66 | 66 | |

| SD | .852 | .997 | .810 | 1.008 | 1.043 | .706 | .640 | .862 | |

| form 6 | Mean | 2.74 | 3.00 | 2.23 | 3.08 | 2.70 | 2.77 | 2.92 | 3.22 |

| N | 88 | 88 | 88 | 88 | 88 | 88 | 88 | 88 | |

| SD | .890 | .994 | .798 | .834 | 1.063 | .739 | .776 | .809 | |

| form 7 | Mean | 2.84 | 2.99 | 2.40 | 3.02 | 3.00 | 2.83 | 3.20 | 3.56 |

| N | 81 | 81 | 81 | 81 | 81 | 81 | 81 | 81 | |

| SD | .941 | 1.066 | .918 | 1.183 | 1.275 | .985 | .781 | .962 | |

| form 8 | Mean | 2.91 | 3.24 | 2.41 | 3.03 | 2.96 | 3.06 | 3.13 | 3.46 |

| N | 70 | 70 | 70 | 70 | 70 | 70 | 70 | 70 | |

| SD | .794 | 1.122 | 1.042 | 1.007 | 1.069 | .866 | .883 | .912 | |

| form 9 | Mean | 2.67 | 2.86 | 2.09 | 2.68 | 2.91 | 2.77 | 2.95 | 3.35 |

| N | 57 | 57 | 57 | 57 | 57 | 57 | 57 | 57 | |

| SD | .893 | 1.109 | .635 | .909 | 1.040 | .866 | .789 | .916 | |

| form 10 | Mean | 2.58 | 3.16 | 2.13 | 2.87 | 3.55 | 2.84 | 3.03 | 3.37 |

| N | 38 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 38 | |

| SD | .858 | 1.366 | .777 | 1.070 | 1.245 | .973 | .822 | .942 | |

| form 11 | Mean | 3.13 | 3.33 | 2.67 | 2.80 | 3.53 | 3.33 | 3.27 | 3.40 |

| N | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | |

| SD | 1.060 | .976 | 1.113 | 1.146 | 1.060 | 1.397 | .961 | .910 | |

| form 12 | Mean | 2.40 | 3.70 | 2.80 | 2.30 | 2.80 | 2.60 | 3.30 | 3.50 |

| N | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | |

| SD | .966 | .675 | 1.229 | .675 | 1.135 | .966 | 1.059 | 1.354 | |

| Total | Mean | 2.89 | 2.86 | 2.41 | 3.16 | 2.72 | 2.64 | 2.90 | 3.23 |

| N | 738 | 738 | 738 | 738 | 738 | 738 | 738 | 738 | |

| SD | .900 | 1.099 | .858 | 1.033 | 1.109 | .846 | .774 | .935 | |

| N | Mean | Std. Deviation | Variance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mother | 738 | 3.57 | 1.901 | 3.615 |

| Father | 738 | 5.25 | 1.696 | 2.878 |

| Other children in the family | 738 | 6.14 | 1.403 | 1.968 |

| Grandparents | 738 | 6.26 | 1.454 | 2.115 |

| Teachers | 738 | 4.25 | 1.787 | 3.193 |

| Other people | 738 | 6.50 | 1.348 | 1.816 |

| Valid N (listwise) | 738 |

| Yes, Regularly | Minimally and Irregularly | No | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regular information on how remote learning will be organized | 377 | 238 | 107 |

| Guidelines on the use of digital tools | 143 | 154 | 410 |

| Guidelines on the use of conferencing tools (Zoom, Skype, Teams, etc.) | 145 | 145 | 416 |

| Online courses to help parents understand how to use digital tools and learning materials | 23 | 53 | 634 |

| Online courses to help students understand how to use digital tools and learning materials | 43 | 84 | 581 |

| Information on how to support the student during remote learning | 138 | 175 | 395 |

| Mean | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Form | Regular Information on How Remote Learning Will Be Organized | Guidelines on the Use of Digital Tools | Guidelines on the Use of Conferencing Tools (Zoom, Skype, Teams, etc.) | Online Courses to Help Parents Understand How to Use Digital Tools and Learning Materials | Online Courses to Help Students Understand How to Use Digital Tools and Learning Materials | Information on How to Support the Student during Remote Learning |

| form 1 | 2.40 | 2.42 | 2.92 | 2.82 | 2.48 | |

| form 2 | 1.66 | 2.43 | 2.48 | 2.88 | 2.84 | 2.43 |

| form 3 | 1.63 | 2.47 | 2.36 | 2.95 | 2.89 | 2.36 |

| form 4 | 1.83 | 2.43 | 2.41 | 2.93 | 2.74 | 2.49 |

| form 5 | 1.62 | 2.40 | 2.43 | 2.89 | 2.78 | 2.37 |

| form 6 | 1.46 | 2.29 | 2.42 | 2.82 | 2.77 | 2.15 |

| form 7 | 1.59 | 2.28 | 2.38 | 2.81 | 2.77 | 2.24 |

| form 8 | 1.56 | 2.45 | 2.35 | 2.90 | 2.77 | 2.44 |

| form 9 | 1.55 | 2.28 | 2.25 | 2.69 | 2.57 | 2.27 |

| form 10 | 1.65 | 2.47 | 2.42 | 2.89 | 2.72 | 2.56 |

| form 11 | 1.71 | 2.36 | 2.29 | 2.50 | 2.21 | 2.36 |

| form 12 | 1.33 | 1.78 | 1.67 | 2.56 | 2.33 | 1.89 |

| Total | 1.63 | 2.38 | 2.38 | 2.86 | 2.76 | 2.36 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Daniela, L.; Rubene, Z.; Rūdolfa, A. Parents’ Perspectives on Remote Learning in the Pandemic Context. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3640. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073640

Daniela L, Rubene Z, Rūdolfa A. Parents’ Perspectives on Remote Learning in the Pandemic Context. Sustainability. 2021; 13(7):3640. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073640

Chicago/Turabian StyleDaniela, Linda, Zanda Rubene, and Arta Rūdolfa. 2021. "Parents’ Perspectives on Remote Learning in the Pandemic Context" Sustainability 13, no. 7: 3640. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073640

APA StyleDaniela, L., Rubene, Z., & Rūdolfa, A. (2021). Parents’ Perspectives on Remote Learning in the Pandemic Context. Sustainability, 13(7), 3640. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073640