The Restorative Effect of the Presence of Greenery on the Classroom in Children’s Cognitive Performance

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review

1.2. Objectives

2. Methodology

2.1. Study 1

2.1.1. Hypotheses

2.1.2. Participants and Contexts

2.1.3. Measurements

- (1)

- Sustainable and selective attention—The Bell test [43] is a standardized measure of selective and sustained attention, suitable for primary school children. The test consists of an A4 sheet, filled with 280 black drawings of different symbols (e.g., tree, horse, apple, bell), of which 35 are bells. The task of attention is to mark all the bells with a pencil in a period of 120s. The attention score is the total number of marked bells, ranging from 0 to 35. Badly marked symbols are not considered;

- (2)

- Working memory—Digital span test was used to evaluate working memory (in WISC-IV, Wechsler intelligence scale for children). It is a standardized measure for attention and concentration, connected with the maintenance of information and working memory. This task is originally administered individually, being here collectively administered in the classroom context (as previously used by [6]). Children are read a series of numbers, and then write them on a sheet of paper (instead of repeating them aloud as in the original version). The set of digits that must be registered in the same order (DSF) as shown is composed of five series of digits (from 2 to 6 digits) and the registration in reverse order (DSB) is composed of four series of digits (from 2 to 5 digits). As in the original task, the total score is calculated as the sum of the series accurately written (DSF- Digital span forward and DSB- Digital span backward);

- (3)

- Classroom Evaluation—three questions were asked to evaluate the classroom (“do you like your classroom?”, “Do you think your classroom is beautiful?”, “Do you think your classroom is cheerful?”). The students answered a 6-point graphical scale (emotion mood scale), which presented drawings of faces that varied between a big smile or a crying face. Cronbach’s alpha of the scale revealed a value of 0.867, which is considered a good value;

- (4)

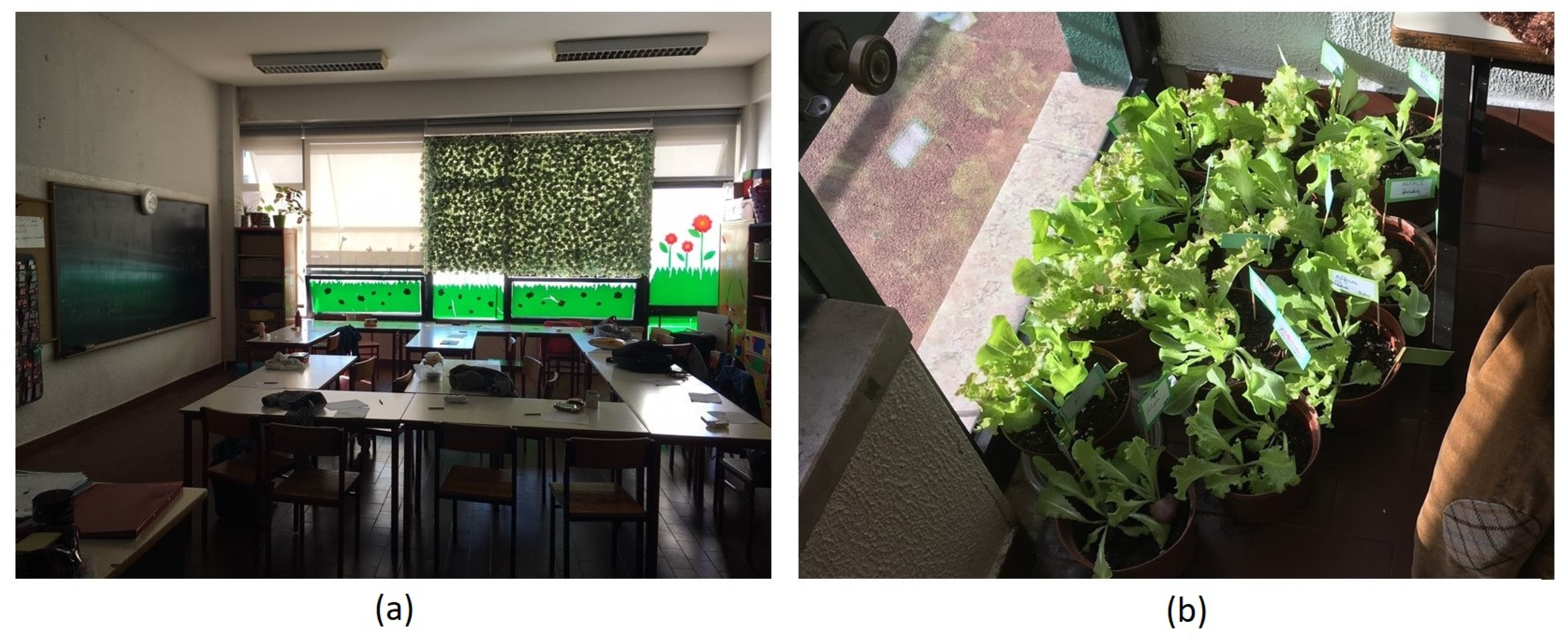

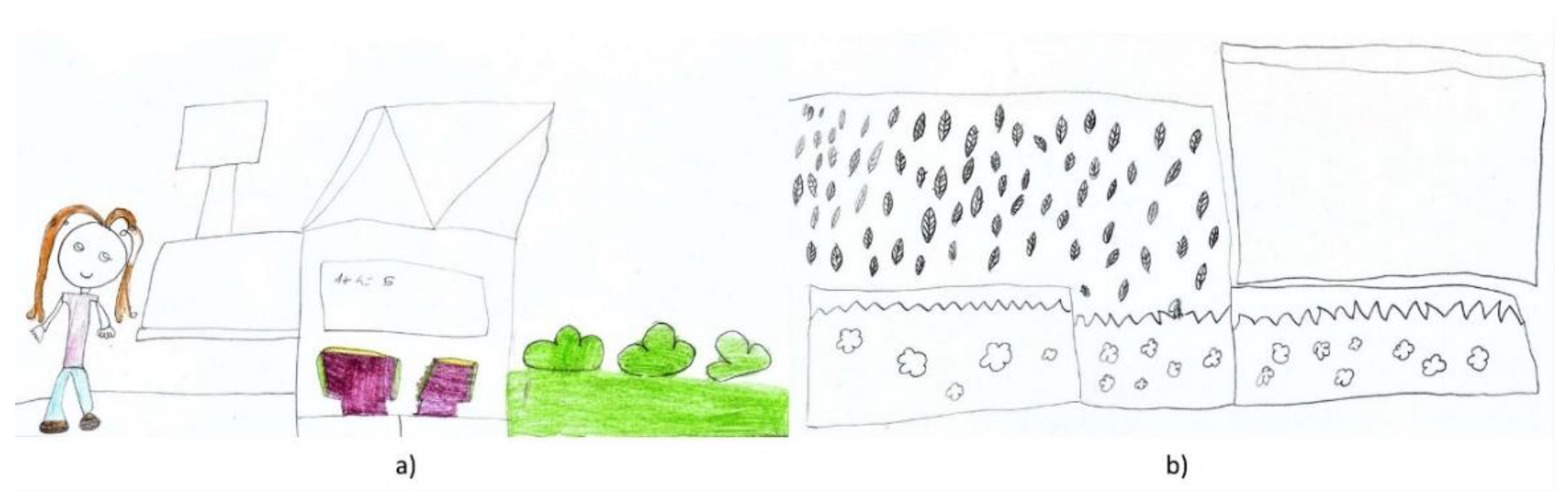

- Classroom drawing—Students were asked to draw a picture of their classroom on a white A4 sheet for 20 min. The purpose of this request was to verify in each of the evaluation moments whether the children included elements of greenery in the drawing, namely, whether in T2 they included the green wall, and in T3 they included the green wall and vegetable pots. The evaluation of the drawings was carried out by two researchers, which identified the green elements present in the drawing and categorized them into three categories: green wall, vegetable pots, other elements of greenery (e.g., vases, flowerpots, drawings or pictures with flowers).

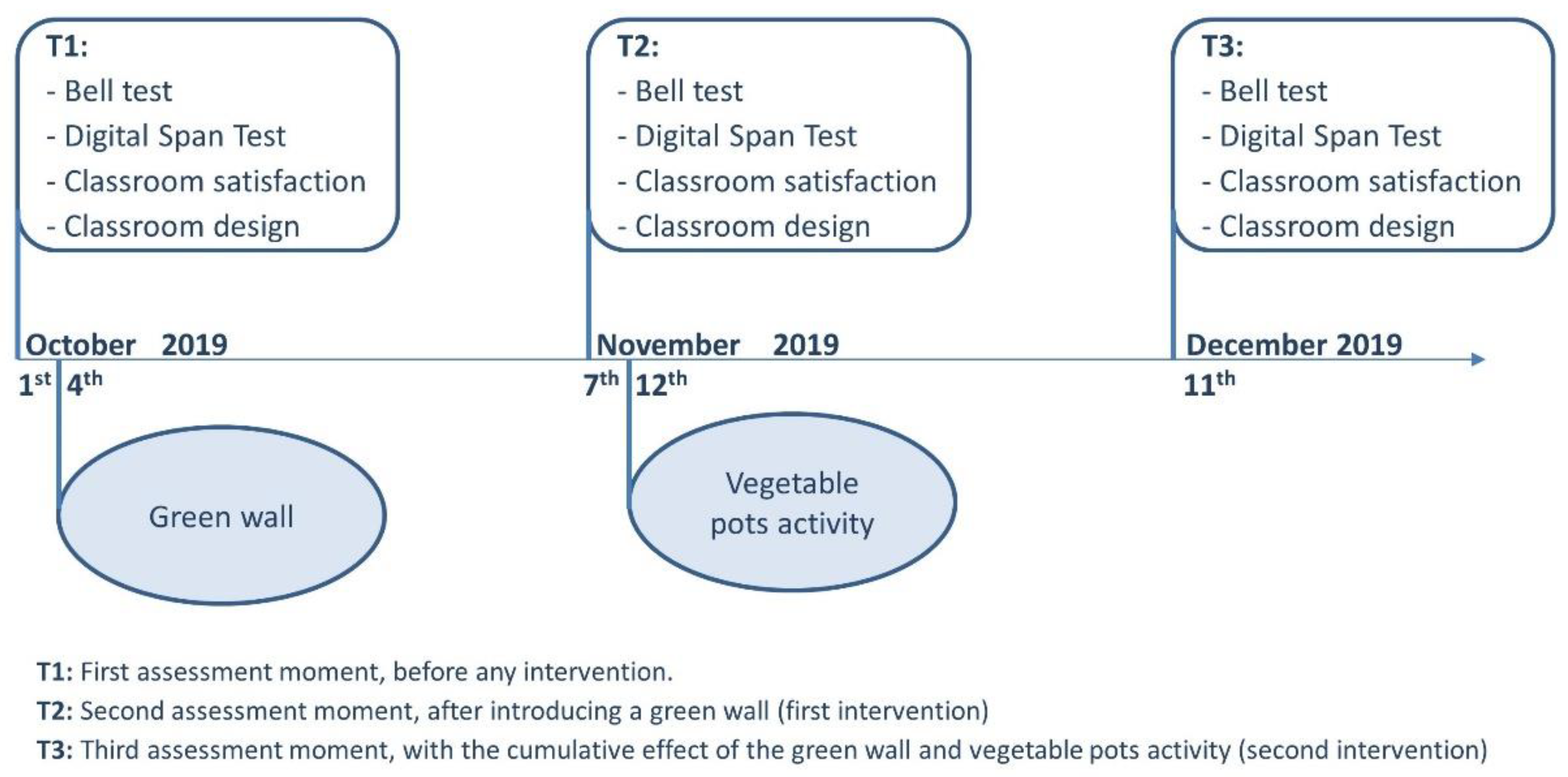

2.1.4. Procedure

2.2. Study 2

2.2.1. Hypotheses

2.2.2. Participants and Contexts

3. Results

3.1. Study 1

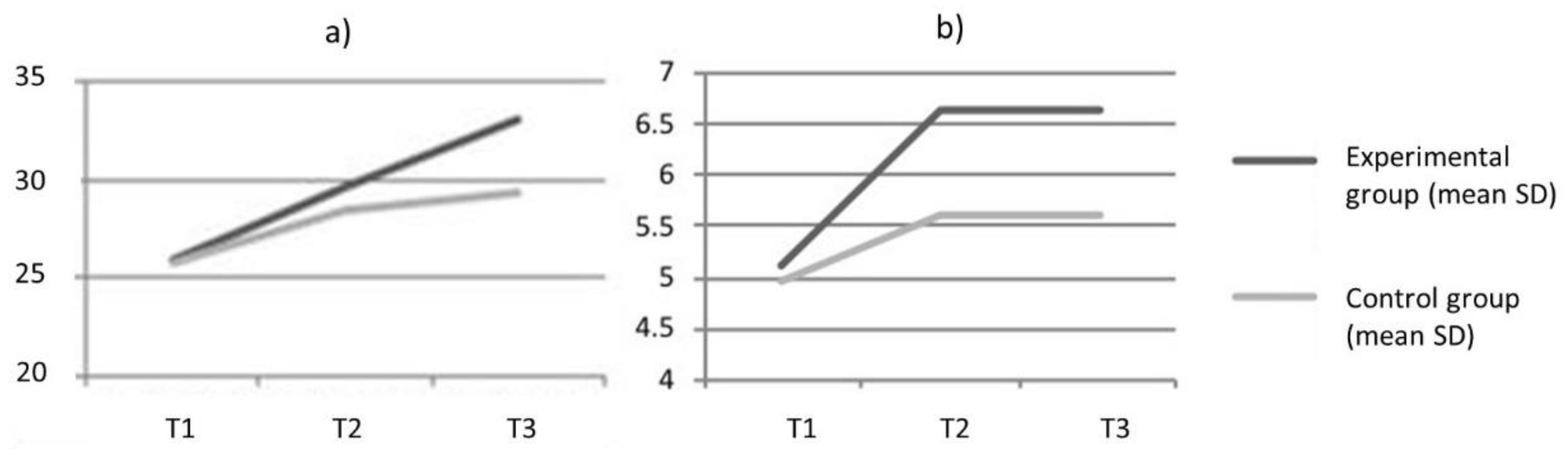

3.1.1. H1 and H2—Sustained and Selective Attention

3.1.2. H3 and H4—Working Memory

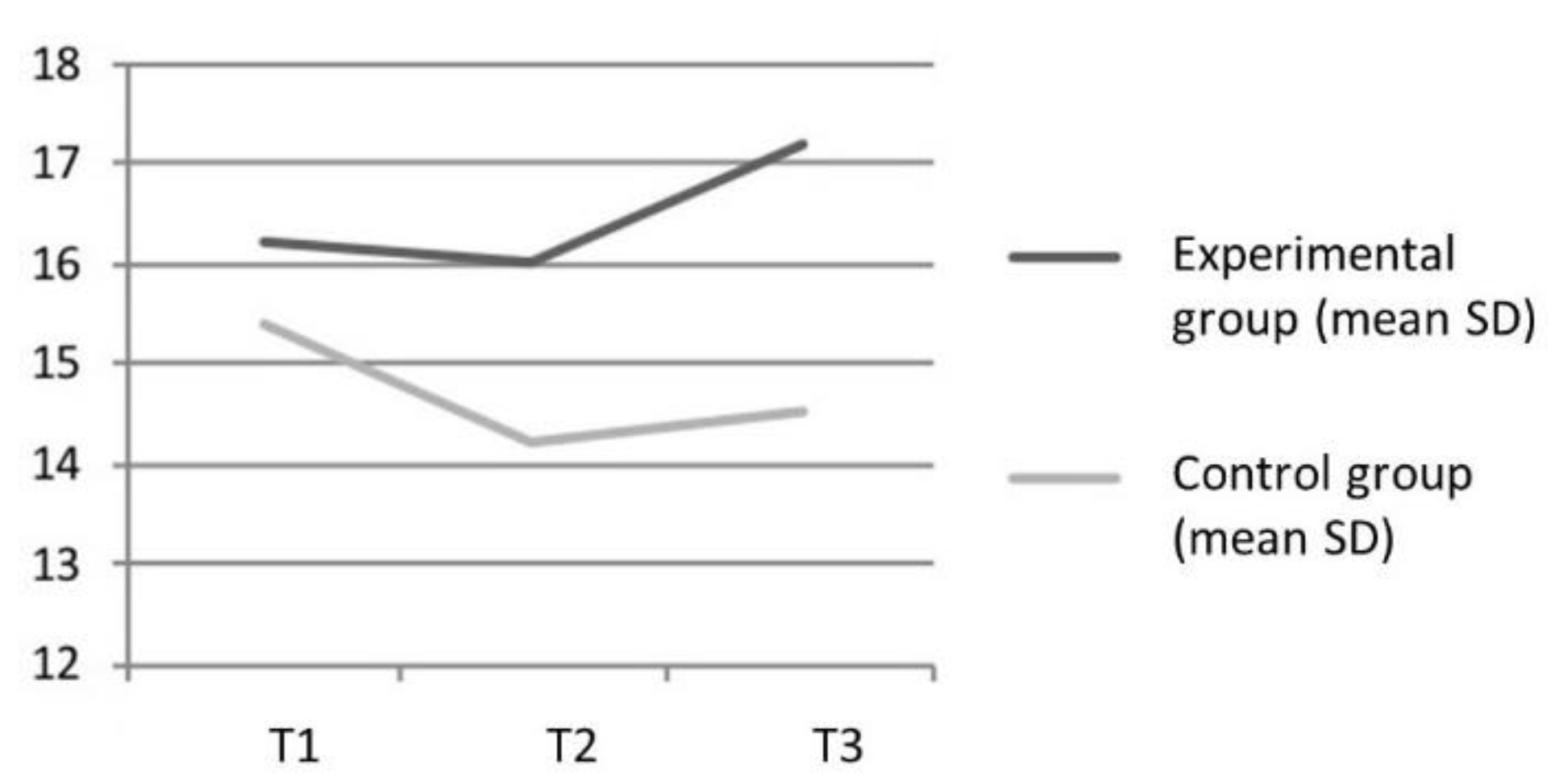

3.1.3. H5 and H6—Satisfaction

3.1.4. Classroom Drawing—Presence of Natural Elements

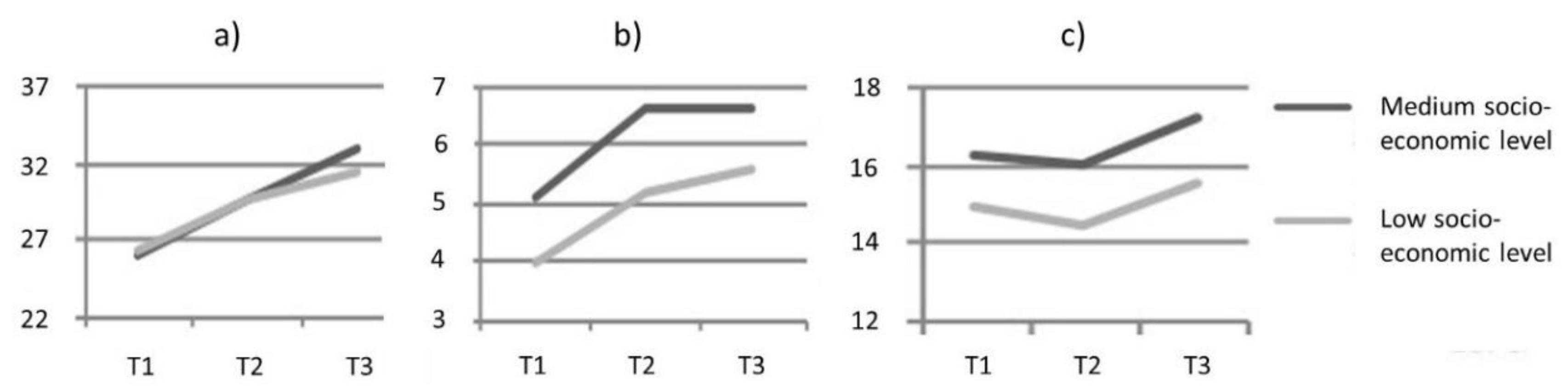

3.2. Study 2

3.2.1. H1 and H2—Sustained and Selective Attention

3.2.2. H3 and H4—Working Memory

3.2.3. H5 and H6—Satisfaction

3.2.4. H7—Classroom Drawing—Presence of Natural Elements

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kuo, F.E. Coping with Poverty. Environ. Behav. 2001, 33, 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, F.E.; Sullivan, W.C. Environment and Crime in the Inner City. Environ. Behav. 2001, 33, 343–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, M.B.; Martin, M.D.; Sajady, M.A. Implementing Green Walls in Schools. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, S. The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amicone, G.; Petruccelli, I.; De Dominicis, S.; Gherardini, A.; Costantino, V.; Perucchini, P.; Bonaiuto, M. Green Breaks: The Restorative Effect of the School Environment’s Green Areas on Children’s Cognitive Performance. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staats, H. Restorative Environments. In Restorative Environments; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hartig, T.; Korpela, K.; Evans, G.W.; Gärling, T. A measure of restorative quality in environments. Scand. House Plan. Res. 1997, 14, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, T.R.; Maguire, C.P.; Nebel, M.B. Assessing the restorative components of environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collado, S.; Corraliza, J.A. Children’s Restorative Experiences and Self-Reported Environmental Behaviors. Environ. Behav. 2013, 47, 38–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S.; Ryan, R. With People in Mind: Design and Management of Everyday Nature; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Han, K.-T. Influence of Limitedly Visible Leafy Indoor Plants on the Psychology, Behavior, and Health of Students at a Junior High School in Taiwan. Environ. Behav. 2008, 41, 658–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, L.; Keena, K.; Pevec, I.; Stanley, E. Green schoolyards as havens from stress and resources for resilience in childhood and adolescence. Health Place 2014, 28, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, R. Does Access to Green Space Impact the Mental Well-being of Children: A Systematic Review. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2017, 37, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrus, G.; Passiatore, Y.; Pirchio, S.; Scopelliti, M. Contact with nature in educational settings might help cognitive functioning and promote positive social behaviour. El contacto con la naturaleza en los contextos educativos podría mejorar el funcionamiento cognitivo y fomentar el comportamiento social positivo. Psyecology 2015, 6, 191–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Sullivan, W.C. Impact of views to school landscapes on recovery from stress and mental fatigue. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 148, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mårtensson, F.; Boldemann, C.; Söderström, M.; Blennow, M.; Englund, J.-E.; Grahn, P. Outdoor environmental assessment of attention promoting settings for preschool children. Health Place 2009, 15, 1149–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, F.E.; Taylor, A.F. A Potential Natural Treatment for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: Evidence from a National Study. Am. J. Public Health 2004, 94, 1580–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dadvand, P.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J.; Esnaola, M.; Forns, J.; Basagaña, X.; Alvarez-Pedrerol, M.; Rivas, I.; López-Vicente, M.; Pascual, M.D.C.; Su, J.; et al. Green spaces and cognitive development in primary schoolchildren. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 7937–7942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akpinar, A. How is high school greenness related to students’ restoration and health? Urban For. Urban Green. 2016, 16, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corraliza, J.A.; Collado, S.; Bethelmy, L. Nature as a Moderator of Stress in Urban Children. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 38, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelz, C.; Evans, G.W.; Röderer, K. The Restorative Effects of Redesigning the Schoolyard. Environ. Behav. 2013, 47, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.F.; Kuo, F.E.; Sullivan, W.C. Views of nature and self-discipline: Evidence from inner city children. J. Environ. Psychol. 2002, 22, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, M.; Browning, M.H.E.M.; Penner, M.L. Do Lessons in Nature Boost Subsequent Classroom Engagement? Refueling Students in Flight. Front. Psychol. 2018, 8, 2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckworth, A.L.; Seligman, M.E.P. Self-discipline gives girls the edge: Gender in self-discipline, grades, and achievement test scores. J. Educ. Psychol. 2006, 98, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuoka, R.H. Student performance and high school landscapes: Examining the links. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010, 97, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrus, G.; Pirchio, S.; Passiatore, Y.; Mastandrea, S.; Scopelliti, M.; Bartoli, G. Contact with Nature and Childrens Wellbeing in Educational Settings. J. Soc. Sci. 2012, 8, 304–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hodson, C.B.; Sander, H.A. Green urban landscapes and school-level academic performance. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 160, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-D.; McNeely, E.; Cedeño-Laurent, J.G.; Pan, W.-C.; Adamkiewicz, G.; Dominici, F.; Lung, S.-C.C.; Su, H.-J.; Spengler, J.D. Linking Student Performance in Massachusetts Elementary Schools with the “Greenness” of School Surroundings Using Remote Sensing. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e108548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, W.T.V.; Tam, T.Y.T.; Pan, W.-C.; Wu, C.-D.; Lung, S.-C.C.; Spengler, J.D. How is environmental greenness related to students’ academic performance in English and Mathematics? Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 181, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.-T. Influence of passive versus active interaction with indoor plants on the restoration, behaviour and knowledge of students at a junior high school in Taiwan. Indoor Built Environ. 2017, 27, 818–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-Y.; Song, J.-S.; Kim, H.-D.; Yamane, K.; Son, K.-C. Effects of Interior Plantscapes on Indoor Environments and Stress Level of High School Students. J. Jpn. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2008, 77, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Berg, A.E.V.D.; Wesselius, J.E.; Maas, J.; Tanja-Dijkstra, K. Green Walls for a Restorative Classroom Environment: A Controlled Evaluation Study. Environ. Behav. 2016, 49, 791–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohr, V.I.; Pearson-Mims, C.H.; Goodwin, G.K. Interior Plants May Improve Worker Productivity and Reduce Stress in a Windowless Environment. J. Environ. Hortic. 1996, 14, 97–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dravigne, A.; Waliczek, T.M.; Lineberger, R.; Zajicek, J. The Effect of Live Plants and Window Views of Green Spaces on Employee Perceptions of Job Satisfaction. HortScience 2008, 43, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bringslimark, T.; Hartig, T.; Patil, G.G. The psychological benefits of indoor plants: A critical review of the experimental literature. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 422–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, J.; Burchett, M.; Torpy, F. Plants in the Classroom Can Improve Student Performance. National Interior Plantscape Association 2010. Available online: http://www.wolvertonenvironmental.com/Plants-Classroom.pdf (accessed on 17 February 2021).

- Doxey, J.S.; Waliczek, T.M.; Zajicek, J.M. The Impact of Interior Plants in University Classrooms on Student Course Performance and on Student Perceptions of the Course and Instructor. HortScience 2009, 44, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fjeld, T. The Effect of Interior Planting on Health and Discomfort among Workers and School Children. HortTechnology 2000, 10, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Mattson, R.H. Stress recovery effects of viewing red-flowering geraniums. J. Ther. Hortic. 2002, 13, 4–12. [Google Scholar]

- Hung, M.F.; Chang, C.Y. The Effect of Plants on Preschool Children’s Attention in the Classroom. Hortic. NCHU 2002, 27, 77–86. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, T.-Y.J.; Chiang, Y.-C. Well-being, health and urban coherence-advancing vertical greening approach toward resilience: A design practice consideration. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 182, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biancardi, A.; Stoppa, E. Il test delle Campanelle modificato: Una proposta per lo studio dell’attenzione in etá evolutiva. Psichiatr. dell’Infanzia dell’Adolescenza 1997, 64, 73–84. [Google Scholar]

- Bagot, K.L.; Allen, F.C.L.; Toukhsati, S. Perceived restorativeness of children’s school playground environments: Nature, playground features and play period experiences. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 41, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S. Visual landscapes and psychological well-being. Landsc. Res. 1979, 4, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S. Natural versus urban scenes: Some psychophysiological effects. Environ. Behav. 1981, 13, 523–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danforth, P.; Waliczek, T.; Macey, S.; Zajicek, J. The effect of the National Wildlife Federation’s Schoolyard Habitat Program on fourth grade students’ standardized test scores. HortTechnology 2008, 18, 356–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemmer, C.; Waliczek, T.; Zajicek, J. Growing Minds: The Effect of a School Gardening Program on the Science Achievement of Elementary Students. HortTechnology 2005, 15, 448–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.M.; Gaston, K.J.; Warren, P.H.; Thompson, K. Urban domestic gardens (V): Relationships between landcover composition, housing and landscape. Landsc. Ecol. 2005, 20, 235–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teotónio, I.; Cabral, M.; Cruz, C.O.; Silva, C.M. Decision support system for green roofs investments in residential buildings. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 249, 119365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsadek, M.; Liu, B.; Lian, Z. Green façades: Their contribution to stress recovery and well-being in high-density cities. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 46, 126446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Moment | Experimental Group (Mean, SD) | Control Group (Mean, SD) | T | Sig | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sustained selective attention | T1 | 26.00 | 25.75 | 0.242 | 0.810 |

| T2 | 29.69 | 28.53 | 1.527 | 0.131 | |

| T3 | 33.00 | 29.30 | 5.560 | 0.000 | |

| Working memory | T1 | 5.13 | 4.95 | 0.671 | 0.504 |

| T2 | 6.62 | 5.60 | 3.594 | 0.001 | |

| T3 | 6.64 | 5.62 | 3.126 | 0.003 | |

| Classroom satisfaction | T1 | 16.20 | 15.37 | 1.227 | 0.223 |

| T2 | 16.00 | 14.20 | 2.116 | 0.037 | |

| T3 | 17.18 | 14.50 | 3.626 | 0.000 |

| Group | T1 | T2 | T3 | F | Sig | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sustained selective attention | Experimental Group | 26.00A | 29.69B | 33.00C | 91.889 | 0.000 |

| Control Group | 25.75A | 28.53B | 29.30B | 14.142 | 0.000 | |

| Working memory | Experimental Group | 5.13A | 6.62B | 6.64B | 40.979 | 0.000 |

| Control Group | 4.95a | 5.60b * | 5.62b | 4.194 | 0.019 | |

| Classroom satisfaction | Experimental Group | 16.20 | 16.00a * | 17.18b * | 4.415 | 0.015 |

| Control Group | 15.37 | 14.20 | 14.50 | 2.759 | 0.070 |

| Moment | Classroom Satisfaction | Experimental Group | Control Group |

|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | Other green elements | 10 (22%) | 7 (17.5%) |

| T2 | Other green elements | 11 (24%) | 5 (12.5) |

| Green wall | 1 (2%) | 0 | |

| T3 | Other green elements | 16 (36%) | 3 (7.5%) |

| Green wall | 5 (11%) | 0 | |

| Vegetable pots | 20 (44%) | 0 |

| Groups | T1 | T2 | T3 | F | Sig | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sustained selective attention | Middle-class school | 26.00A | 29.69B | 33.00C | 91.889 | 0.000 |

| Low-class school | 26.37A | 29.63B | 31.33C | 19.302 | 0.000 | |

| Working memory | Middle-class school | 5.13A | 6.62B | 6.64B | 40.979 | 0.000 |

| Low-class school | 3.97A | 5.17B | 5.60B | 15.371 | 0.000 | |

| Classroom satisfaction | Middle-class school | 16.2 | 16.00a * | 17.18b * | 4.415 | 0.015 |

| Low-class school | 14.97 | 14.47 | 15.57 | 1.006 | 0.372 |

| Moment | Middle-Class School (Mean) | Low-Class School (Mean) | t | Sig | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sustained selective attention | T1 | 26.00 | 26.37 | −0.325 | 0.746 |

| T2 | 29.69 | 29.63 | 0.060 | 0.952 | |

| T3 | 33.00 | 31.33 | 2.722 | 0.008 | |

| Working memory | T1 | 5.13 | 3.97 | 4.226 | 0.000 |

| T2 | 6.62 | 5.17 | 4.512 | 0.000 | |

| T3 | 6.64 | 5.60 | 3.160 | 0.002 | |

| Classroom satisfaction | T1 | 16.20 | 14.97 | 1.464 | 0.147 |

| T2 | 16.00 | 14.47 | 1.624 | 0.109 | |

| T3 | 17.18 | 15.57 | 2.446 | 0.017 |

| Moment | Classroom Satisfaction | Medium-Class School | Lower-Class School |

|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | Other green elements | 10 (22%) | 0 |

| T2 | Other green elements | 11 (24%) | 2 (7%) |

| Green wall | 1 (2%) | 3 (10%) | |

| T3 | Other green elements | 16 (36%) | 2 (7%) |

| Green wall | 5 (11%) | 6 (20%) | |

| Vegetable pots | 20 (44%) | 10 (33%) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bernardo, F.; Loupa-Ramos, I.; Matos Silva, C.; Manso, M. The Restorative Effect of the Presence of Greenery on the Classroom in Children’s Cognitive Performance. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3488. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063488

Bernardo F, Loupa-Ramos I, Matos Silva C, Manso M. The Restorative Effect of the Presence of Greenery on the Classroom in Children’s Cognitive Performance. Sustainability. 2021; 13(6):3488. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063488

Chicago/Turabian StyleBernardo, Fátima, Isabel Loupa-Ramos, Cristina Matos Silva, and Maria Manso. 2021. "The Restorative Effect of the Presence of Greenery on the Classroom in Children’s Cognitive Performance" Sustainability 13, no. 6: 3488. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063488

APA StyleBernardo, F., Loupa-Ramos, I., Matos Silva, C., & Manso, M. (2021). The Restorative Effect of the Presence of Greenery on the Classroom in Children’s Cognitive Performance. Sustainability, 13(6), 3488. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063488