1. Introduction

Groundwater from karst aquifers is considered an important resource and is extensively used for public water supply. In Europe, carbonate terrains occupy about 35% of the land surface, and in some countries karst groundwater contributes up to 50% to the total drinking water supply. In many regions it is the only available freshwater resource [

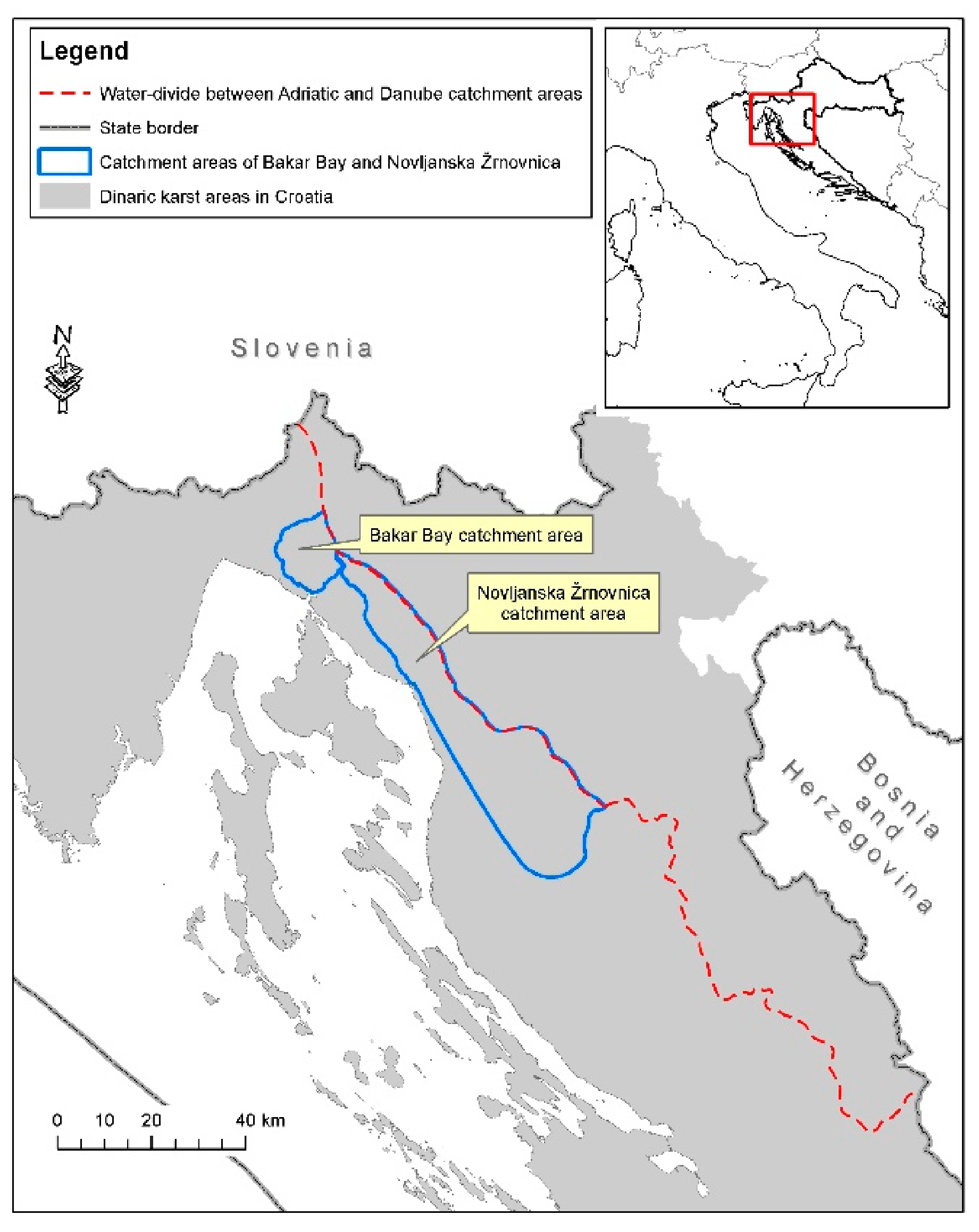

1]. In Croatia almost 50% of all public water supplies are from karst aquifers (

Figure 1; [

2]).

Karst aquifers are particularly vulnerable to contamination because of their thin soils or absence of covering deposits, flow concentration within the epikarst zone and concentrated recharge via swallow holes. As a result, contaminants may easily reach the groundwater and be rapidly transported in karst conduits over large distances [

3]. For these reasons, it is very important to determine the level of vulnerability of karst aquifers for their protection and remediation, but also for spatial planning.

There are two main river basins in Croatia: the Danube River Basin and the Adriatic Sea River Basin. Each of them is further divided into several dozen grouped groundwater bodies, and river basin management plans are developed at that level in accordance with the Water Framework Directive [

4]. Precisely because of this, these basins are a very important for observation of and research on water resources, from the regional to local scales. The catchments shown in this paper are parts of grouped bodies of groundwater, i.e., they must be subjected to a very detailed analysis on a local scale. Therefore, groundwater resources need to be contextualized in multiscalar dimensions. This is an important characteristic of groundwater resources, as well as the fact that they are invisible, and therefore pose an additional challenge to their management and governance [

5].

The first estimates of the intrinsic vulnerability of water resources in Europe, based on the differences in the lithological composition of rocks, were made in 1968 by Margat and in 1970 by Albinet and Margat for France [

6,

7]. Ten years later, Vierhuff and his associates made a similar estimate for West Germany [

8]. During the 1990s, Europe’s first project related exclusively to the protection of karst aquifers was launched [

1]. The project emphasized the importance of a multidisciplinary approach to research into karst areas, using geological, geomorphological, geophysical, hydrological, geochemical and other means of investigation in order to obtain information about the karst environment and dynamics of the groundwater flow. From about 1985 to recent times, researchers worldwide have developed numerous methods and, in the early 2000s, GIS technology started to be used in such analyses. Some of the methods were developed primarily to assess the intrinsic vulnerability of karst aquifers. They were used for the protection of karst aquifers or as one of the fundamental bases for the development of regional spatial plans. Some of these methods include DRASTIC [

9], AVI [

10], GOD [

11,

12], EPIK [

13,

14,

15], the Irish Method [

16], REKS [

17], the Austrian Method [

18], VULK [

19], LEA [

20], PI [

21,

22], COP [

23], SINTACS [

24], The Slovene Method [

25] and CC-PESTO [

26], as well as many other methods. The framework for vulnerability mapping was set up through the project COST 620 [

27].

That methods were applied in several catchments worldwide and, because of the specific characteristics of some karst areas, some of the methods could be applied without modification of the parameters [

28,

29]; whilst others had to have some parameters modified [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]. For some areas, a comparative analysis of the use of several of the most common methods of intrinsic vulnerability mapping has been conducted [

35,

36].

The problem is that only a few of the developed methods can be used for vulnerability analysis of deep karst aquifers, like Dinaric karst aquifers, or in the wider Mediterranean region, but mostly with some limitations. Some of the methods can be used in karst aquifers but some of the parameters used in that multiparameter methods are not fully suitable for specific characteristics of karst aquifers like Dinaric karst aquifers (e.g., large amount of precipitation, depth to groundwater, groundwater dynamics, lack of covering deposits, direct input of surface waters into groundwater through swallow- holes, very large karst springs, etc.).

There are several methods for determining the intrinsic vulnerability of karst aquifers that are frequently used in hydrogeological practice. The Karst Aquifer Vulnerability Assessment (KAVA) method was developed on the same pilot areas for which intrinsic vulnerability maps were made using the COP [

23], SINTACS [

24] and PI [

21,

22] methods. Those methods were tested with the conditions of Dinaric karst deep aquifers and some of them had some limitations, but there were also some very good parameters which were used and modified in the KAVA method.

The PI method [

21,

22] seems at first sight to be simple, but its basic (P and I) parameters require extensive calculation of subparameters, and this creates considerable complexity. This complex method for assessment of the impact of covering soils is unsuited to this region, which mostly lacks covering deposits. Also, the range of values for factor P (recharge) is also unsuitable, because the cutoff point for the maximum precipitation class is only 400 mm/year. All of the Dinaric karst area in Croatia falls into this category, and in some areas the average yearly precipitation is more than 4000 mm. The same problem can also be expected in the other countries in the Dinaric karst region (Slovenia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, Albania), but also in the other karst aquifers in the European part of the Mediterranean area. The surface catchment area maps produced by the PI method are, however, very good and we used this idea in the KAVA method.

The COP method [

23] uses excessive zoning around the main sinkholes in its assessment of concentrated infiltration. The 11 categories, all utilizing a score range from 0 to 1, contrast awkwardly with the three categories used to define the influence of sinking watercourses, and this creates problems in the presentation of aquifer vulnerability.

Although the SINTACS method [

24] seems at first sight very complex, it mostly works well, because each parameter is strictly defined and described in detail, and there is no need to define subparameters. The main objection to the method after implementation in the pilot areas in the Dinaric karst in Croatia was that it used too many geological parameters and with them explained all the other parameters, except the depth to the groundwater (S1) and the topographic slope (S2). This could cause the final map to be very subjective, although the vulnerability map produced for the study area was good.

The Karst Aquifer Vulnerability Assessment method is derived from a combination of parameters adjusted to the specific characteristics of the Dinaric karst aquifers and is designed primarily for assessment of the intrinsic vulnerability of karst aquifers and sources, where the final spatial analysis and vulnerability maps are made with multiparameter GIS technology. The method was developed within the GEF UNEP/MAP MedPartnership Project, UNESCO-IHP sub-component 1.1 “Management of coastal aquifers and groundwater”. The idea of the project was that karstic aquifers make up a large proportion of the aquifers in the Mediterranean region, so developing a new method for their analysis would contribute greatly to hydrogeological practice in that area. This research endeavor was prompted by the high importance of karst aquifers in providing a water supply to a large concentration of the regional population, and by the hope of increasing tourism in the Mediterranean region. In these conditions, it is necessary to harmonize and improve efficiency in the protection of these valuable natural resources in various countries to safeguard the current and future development of the region.

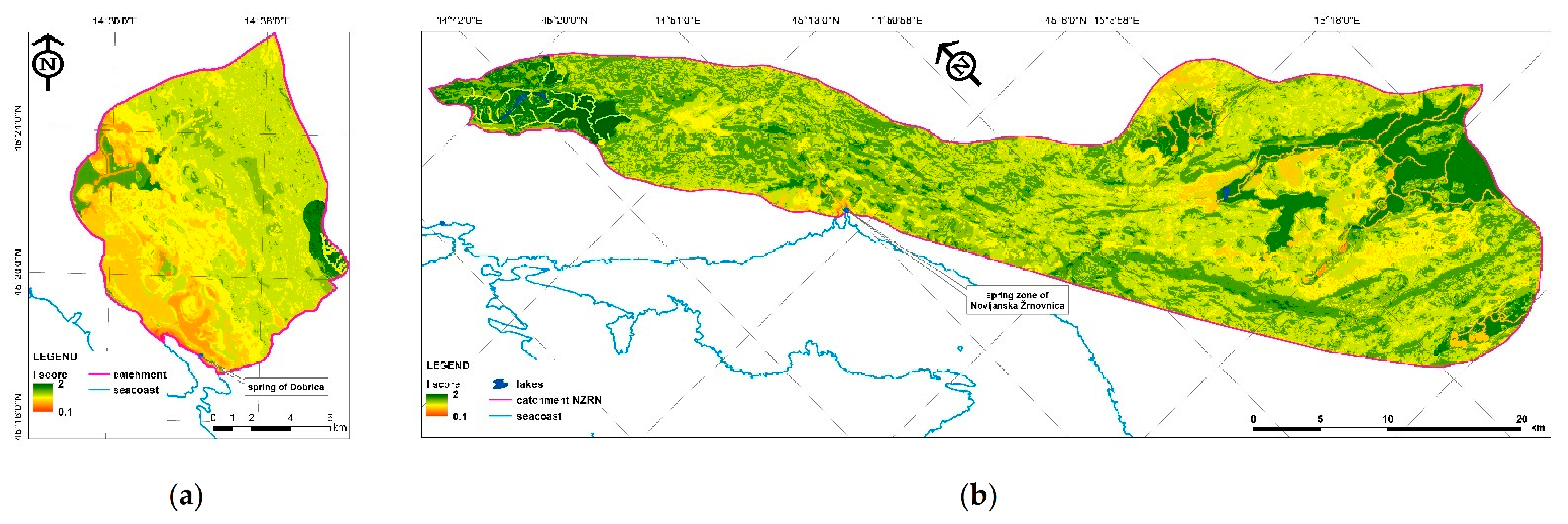

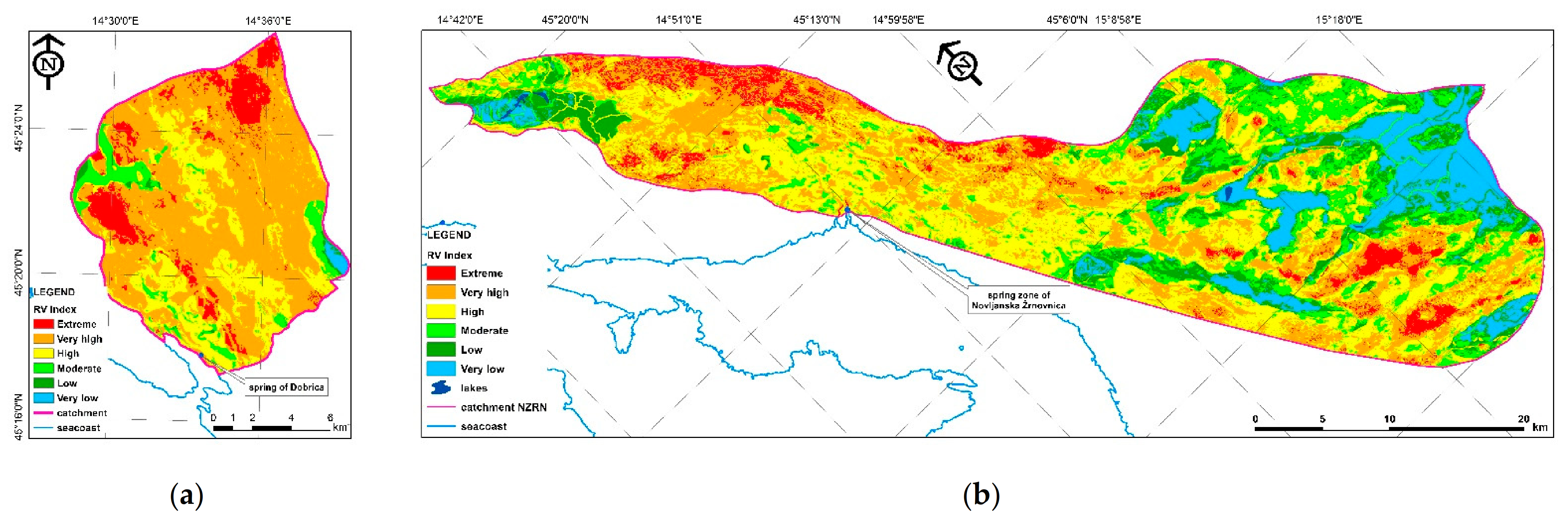

The novel KAVA method was tested on several different catchments in the Dinaric karst region in Croatia, and in this paper we present its application in two neighboring catchment areas in the northern part of the Dinaric karst area in Croatia: the Novljanska Žrnovnica and Bakar Bay catchment areas (

Figure 1).

Although Novljanska Žrnovnica is a typical catchment area of the Dinaric karst in which is represented almost all the karst phenomena and forms involved in the development of the method, it was also necessary to apply the method to another catchment with slightly different characteristics. For this purpose, the Bakar Bay catchment was selected, a smaller karst catchment area situated adjacent to the Novljanska Žrnovnica catchment area.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of the KAVA Method

The KAVA method is based on an origin–pathway–target conceptual model, which was proposed within the project COST 620 [

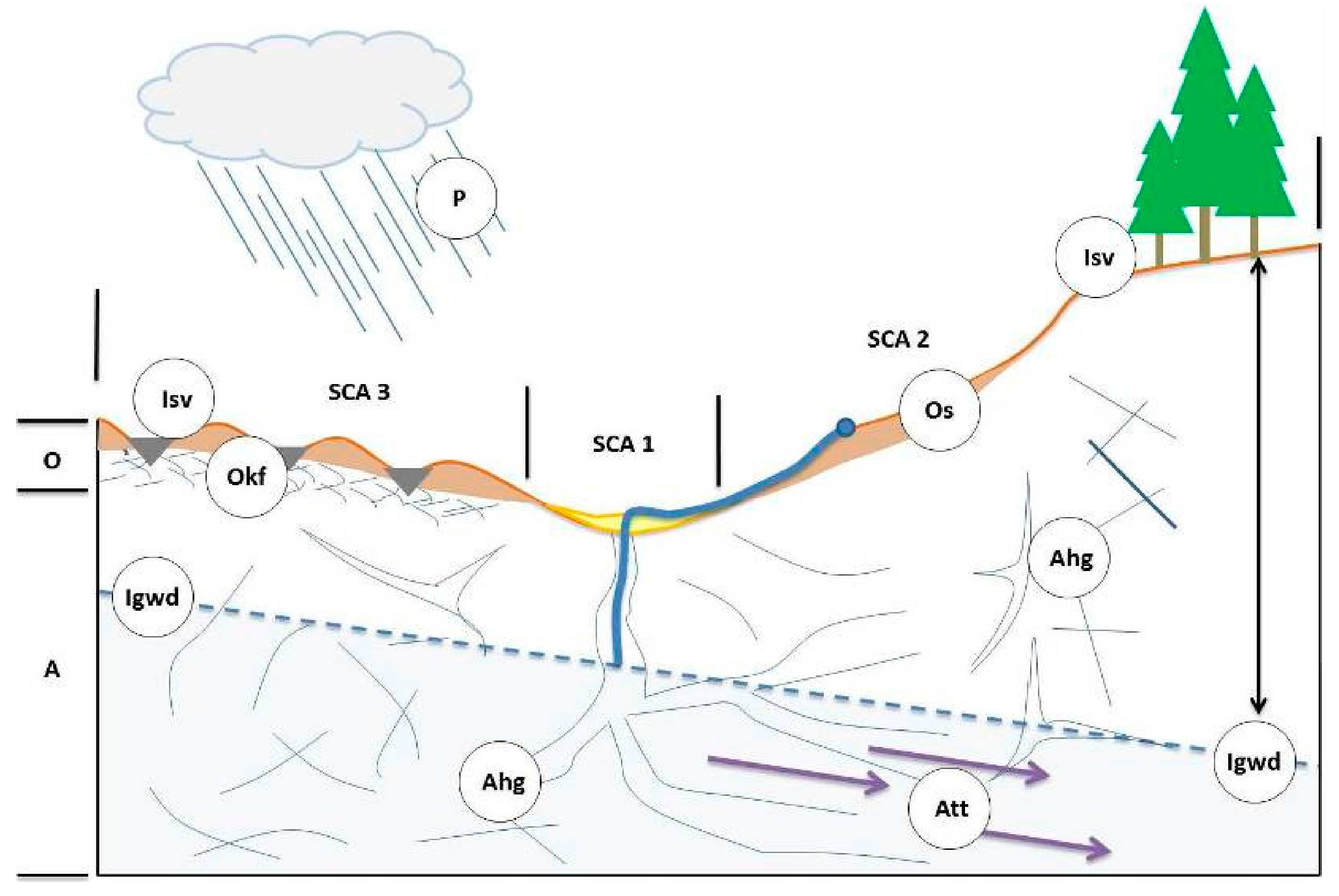

27]. It is primarily designed for assessment of intrinsic vulnerability, with the final spatial analysis and vulnerability maps being made with multiparameter GIS methodology. Four of the basic factors of the KAVA method for assessing intrinsic vulnerability are: overlay protection (O factor), precipitation influence (P factor), infiltration conditions (I factor) and aquifer conditions (A factor) (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

Unlike the European approach [

27] and other existing methods for intrinsic vulnerability assessment, in the KAVA method the unsaturated and saturated parts of karst aquifers are treated together. There are several reasons for this, but the primary one is due to the simplification of the overall model (the principle of Occam’s razor). Given that the carbonate karst aquifer is a highly heterogeneous and anisotropic medium, without a sufficient number of quite expensive and detailed exploration wells, which would provide sufficient certainty for the determination of groundwater levels, the separation of the unsaturated and saturated parts of karst aquifers is hardly feasible. For these reasons, the boundary between unsaturated and saturated zones in karst aquifers is often determined empirically or approximately, and the use of unsaturated zone thickness is generally an unreliable parameter, which is the lack of all models that use it.

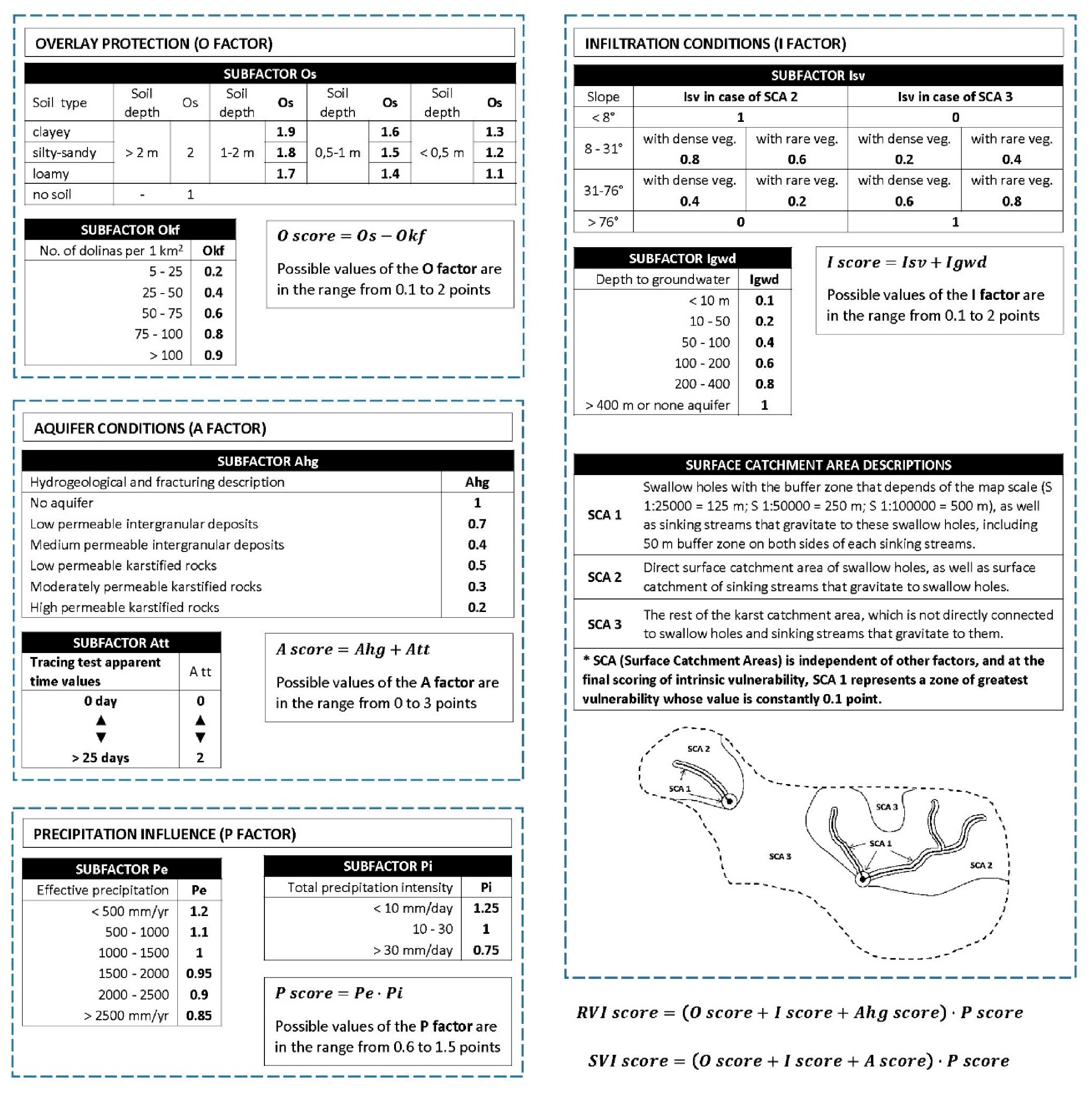

2.2. Overlay Protection (O Factor)

The O factor defines the protective role of covering layers of karst catchments, the hydrogeological protective role of which can vary from place to place due to the different characteristics of subsurface zones in the condition of open karst. Therefore, when determining the value of the O factor, two basic data sets are used: the subfactor Os (soils) and subfactor Okf (karst features).

The Subfactor Os (soils) is evaluated to present the protective role of the covering soil. It is a biologically active zone of the aquifer in relation to the ground surface, which may result in detention and/or partial degradation of potential contaminants on the surface or at the surface. For this reason, when designing a karst intrinsic vulnerability project, it is always necessary to evaluate the protective role of soil cover according to the available soil data. Some of the key parameters required to estimate the protective role of covering soils are soil texture, particle size distribution and thickness of the covering soil.

The Subfactor Os was originally proposed as part of the COP method [

23], in which overlying soil is divided into four basic groups according to its texture and grain size distribution. In the KAVA method, these soil categories are further simplified because the Dinaric karst catchments are mostly without cover deposits. The final assessment and scoring of the

O factor was adapted to additionally estimated characteristics of epikarst zones.

The subfactor Okf (karst features) defines the impact of karstified and highly permeable surface and subsurface zones of karst aquifers on the overall intrinsic vulnerability of karst catchments, i.e., the impacts of epikarst zones. The epikarst zone can vary in thickness from a few meters to tens of meters, and is individually assessed as, due to its creation and the processes that happen in it, it is structurally different from the rest of the karst aquifer.

The problem with the analysis of epikarst zones is that they generally are not visible on the surface and their thickness and distribution can be determined only by detailed geophysical surveys and exploratory drilling. However, their existence is more often determined by the indirect method—by using spatial analysis of karst geomorphological features on the surface, which indicate its origin and development. The most commonly used analysis is the density of sinkholes on the surface. The basic assumption is that an epikarst zone exists even when it is not visible on the surface, as long as there are conditions that enable its development—pure limestone with visible severe open fracture systems, karst geomorphological indicators such as sinkholes, etc. [

37].

The values of the

O factor are obtained by subtracting the subfactor

Okf from the subfactor

Os as shown in Equation (1):

Possible O factor values ranges from 0.1 to 2 points. Very small values (0.1 to 0.5) correspond to the areas where the soil is very poorly developed or absent and where many dolines are present. Small to moderate values (0.5 to 1) correspond to the areas where the soil is developed to a depth of 1 m and many dolines are present, as well as areas where the soil is slightly shallower and fewer dolines are present per km2. Moderate to high values (1 to 1.5) correspond to areas where the soil is mainly developed to a depth of 2 m and fewer dolines are present. Very high values (over 1.5) generally correspond to areas where the soil is developed to a depth of 1 to 2 m and few dolines are present, as well as areas with very deep soils (>2 m) and no occurrence of dolines.

In the preparation of the final intrinsic vulnerability map with the KAVA method, unclassified O factor values must be used.

2.3. Precipitation Influence (P Factor)

The influence of precipitation (P factor) is an external stress applied to the whole vulnerability assessment used in the KAVA method. In assessing the P factor, an effective amount of rainfall must be taken into account. It is the part of the total rainfall that has a real chance of infiltrating from the surface and with percolation sinking into the deeper parts of the karst aquifer.

The effective precipitation impact on the vulnerability is expressed in the form of the Pe subfactor (effective precipitation). In assessing the vulnerability of karst aquifers the most critical factors are considered in the Pe subfactor scoring, namely the high intensity and amount of rainfall that causes rapid infiltration and transport of water with potential contaminants into the deeper parts of the aquifer.

Taking into account the fact that the distribution of total annual rainfall may also further affect the vulnerability of karst catchments, an additional Pi subfactor (precipitation intensity) is also used to determine the total P factor. This allows further modification, as needed, of the effective rainfall influence.

The values of the subfactor Pe (effective precipitation) are determined from the values of the mean effective rainfall in the catchment area. Values ranging from 1000 to 1500 mm/yr are taken as neutral, while all other values can modify the total intrinsic vulnerability of karst catchment (

Figure 3). Data on effective rainfall can be obtained from previous research, meteorological and precipitation maps, etc., as well as through the calculation of many empirical formulas [

38,

39,

40] that take into account the overall mean amount of precipitation, air temperature and other parameters relevant to effective precipitation evaluation.

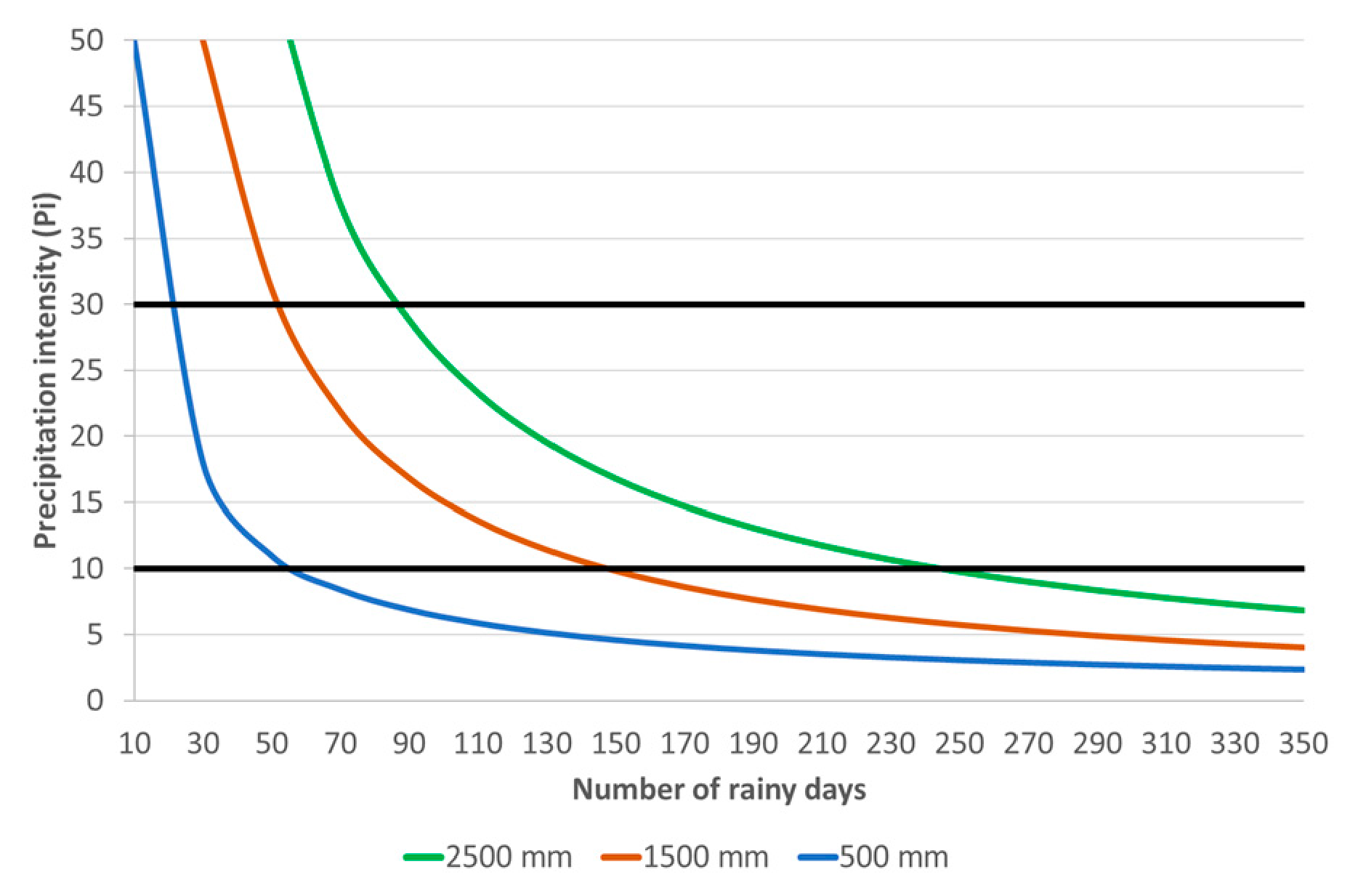

Subfactor

Pi (precipitation intensity) is determined from the values of the mean annual rainfall and the total number of rainy days in the catchment area, using Equation (2):

Fewer rainy days for the same total amount of rainfall causes higher precipitation intensities, which results in the increased intrinsic vulnerability of karst aquifers. In addition, more intense precipitation favors the concentrated infiltration of water into the karst underground, i.e., flushing of the aquifer unsaturated zone. On the other hand, more rainy days causes lower precipitation intensity and more uniform distribution of total rainfall during the year. This reduces the aquifer intrinsic vulnerability due to increased (slower) diffusion infiltration of water into the karst underground. To assess the overall impact of the

Pi subfactor, three categories of rainfall intensity are used (

Figure 3), the principle selection of which is shown in

Figure 4 for three values of the total mean annual rainfall.

The P factor was developed based on the guidelines proposed by the project COST 620 [

27] with a certain simplification of the whole procedure and keeping in mind that precipitations represent external stress, which further modifies the total vulnerability assessment; in the case of intense rainfall this can be a positive effect of dilution of pollution.

P factor values are obtained by multiplying

Pe and

Pi subfactors (Equation (3)):

Possible P factor values range from 0.6 to 1.5.

In the preparation of the final intrinsic vulnerability map with the KAVA method, unclassified P factor values should be used.

2.4. Surface Catchments Areas

The surface catchment area (SCA) parameter is obtained by spatial analysis of hydrological phenomena on the surface of certain karst catchment area. The basis of the analysis is the separation of the main surface catchment areas for swallow-hole zones and the sinking streams that gravitate to them.

After an analysis, karst catchments can be divided at surface into three main areas, according to

Figure 3. In further spatial analyses dependent on these areas, the conditions of diffuse or concentrated infiltration of surface water into the karst underground are estimated (SCA 2 and SCA 3), and the final intrinsic vulnerability map emphasizes the areas of greatest vulnerability (SCA 1), which include sinkholes, sinkhole zones and surface water bodies that affect them.

Depending on the scale of the final intrinsic vulnerability map, the buffer zones around SCA 1s should be defined according to

Figure 3.

2.5. Infiltration Conditions (I Factor)

Assessment of the degree of surface water infiltration into the deeper parts of the karst aquifer depends on many parameters that control the processes of surface and subsurface water flow. The most important are: terrain slopes, properties of overlay deposits, the presence of vegetation and the presence of morphological forms that cause local infiltration anomalies (sinkholes, caves, dolines, etc.).

Taking into account the fact that some of these parameters have been already used in the assessment of the O factor (properties of cover sediments and karst geomorphological forms), the I factor is developed in such a way that its impact on karst catchment vulnerability depends on two distinct yet mutually connected layers: the Isv subfactor (slope and vegetation) and the Igwd subfactor (depth to groundwater).

The Isv subfactor (slope and vegetation) defines conditions at the ground surface that can affect the infiltration of surface water, and consequently conditions that affect the intrinsic vulnerability of the karst catchment, i.e., through this subfactor the influences of the terrain slope and vegetation cover on the infiltration are combined. The Vegetation parameter (v) is used for determination of the areas that are covered with dense or sparse vegetation (

Figure 3). Areas covered by dense vegetation include parts of the catchment area that are covered by forests, bushy forests and bushes, while the rest of the catchment area includes the areas covered by sparse vegetation, as well as those areas where there is no vegetation cover. This information can usually be obtained through spatial analysis of land-use maps or Corine Land Cover (CLC) maps. The slope parameter (s) can be obtained relatively easily from digital elevation models by using spatial analysis methods. After analysis has been conducted, obtained values can be further classified into one of four proposed categories of slopes (

Figure 3).

Slope categories and vegetation classification were developed using only two categories taken from the COP method [

23] because this was the most appropriate method for the catchment areas in the Dinaric karst, with regard to estimation of surface water infiltration.

Given the fact that the Isv subfactor is directly controlled by hydrological conditions on the catchment surface, prior to its overall impact assessment on catchment vulnerability it is necessary to align it with the SCA parameter.

When assessing the Isv in the SCA 2 area, the conditions of concentrated infiltration of water into the karst underground are assumed, because dominant surface runoffs related to concentration and flow of surface water to watercourses and their swallow holes are in this area. In such conditions, the combination of slopes and vegetation provides the Isv subfactor value, which suggests greater vulnerability in cases of major slopes and scarce vegetation (

Figure 3). In real conditions, this means shorter transport time and rapid water infiltration into the karst underground.

When assessing the Isv in the SCA3 area, conditions of diffuse infiltration of water into the karst underground are assumed, because longer retention of water on the catchment surface is dominant in this area. Therefore, the impact assessment of slopes and vegetation is determined in a reverse manner to the previous case. The Isv subfactor values are such that they indicate greater vulnerability in cases of small slopes and scarce vegetation (

Figure 3).

The Igwd subfactor (groundwater depth), through the assessment of the depth to groundwater values, defines the impact (the importance) of the infiltrated surface water on the overall intrinsic vulnerability of a specific karst catchment area, where the values of the subfactor Igwd are not only related to the unsaturated zone, but to the whole aquifer. Although this subfactor is difficult to determine, it is not negligible. A deeper water table means that the impact of infiltrated surface water will be smaller, due to a longer and/or prolonged transport time of potentially contamination water toward the saturated part of the karst aquifer.

For the best assessment of Igwd subfactor values, it is necessary to have a good piesometric boreholes network of the whole catchment area. With such data and with good spatial analysis, it is possible to determine the position of the water table in the karst aquifer and prepare a groundwater depth map (GWDM).

Due to a lack of such data in karst areas, it is very difficult to make accurate groundwater depth maps. In this case, it is possible to estimate the Igwd subfactor based on good knowledge about hydrogeological relations in the karst catchment, particularly using knowledge of the absolute groundwater level in the aquifer. To obtain a final GWDM a map of the absolute level of groundwater is subtracted from the digital terrain model (elevation map). The final groundwater depth map obtained by spatial analyses of boreholes data or by estimation is the base for the scoring of the Igwd subfactor.

Some of the vulnerability assessment methods for intrinsic vulnerability often divide the saturated and unsaturated zones of the aquifer, which is generally reasonable in the case of intergranular aquifers, but not in the case of karst aquifers. In the KAVA method, the exact depth to groundwater is not specified, but the range of values is, which means easier empirical evaluation of this parameter for researchers. This is actually a modified and further simplified version of the approach used in the SINTACS method [

24], which also does not take into account exact values, but the ranges of depth to groundwater.

The I factor values are obtained by summing the subfactors

Igwd and

Isv (which specifically define the SCA 2 and SCA 3 parts of the catchment area), because ultimately the influence of each of these two subfactors complements the other, as shown in Equation (4):

Possible values are in the range of 1.5 to 2, implying that this factor impacts the overall intrinsic vulnerability of karst aquifers in a way that is always decreasing it—the only question is to what extent.

In preparing the final intrinsic vulnerability map with the KAVA method, unclassified I factor values must be used.

2.6. Aquifer Conditions (A Factor)

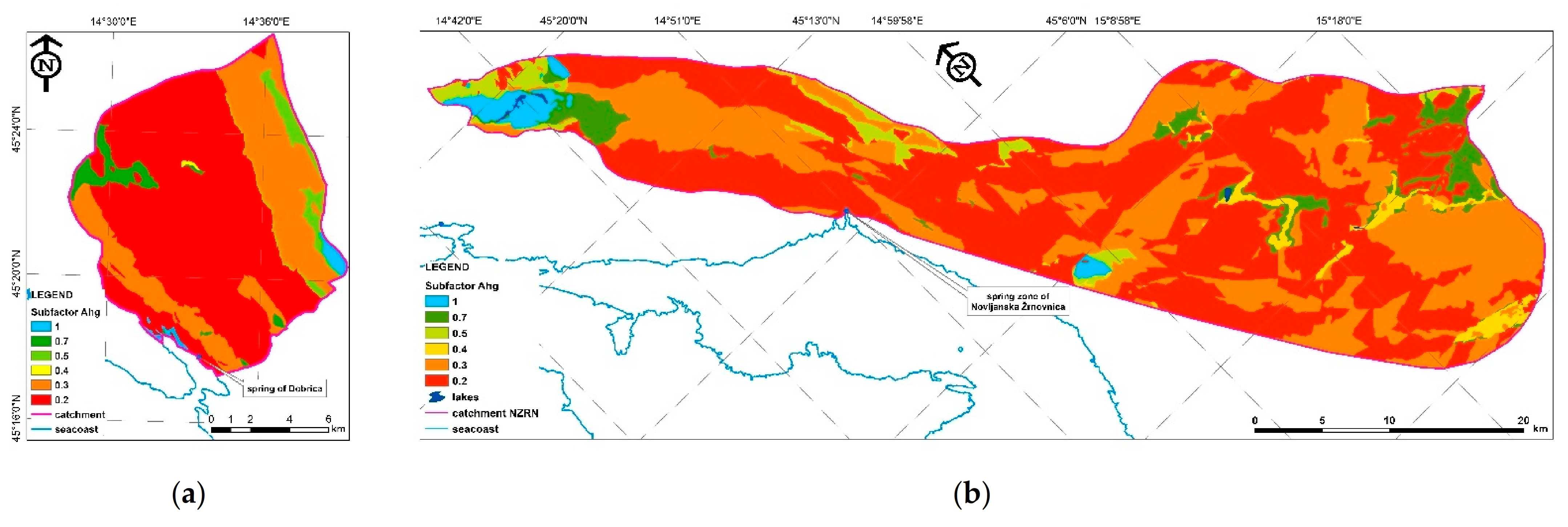

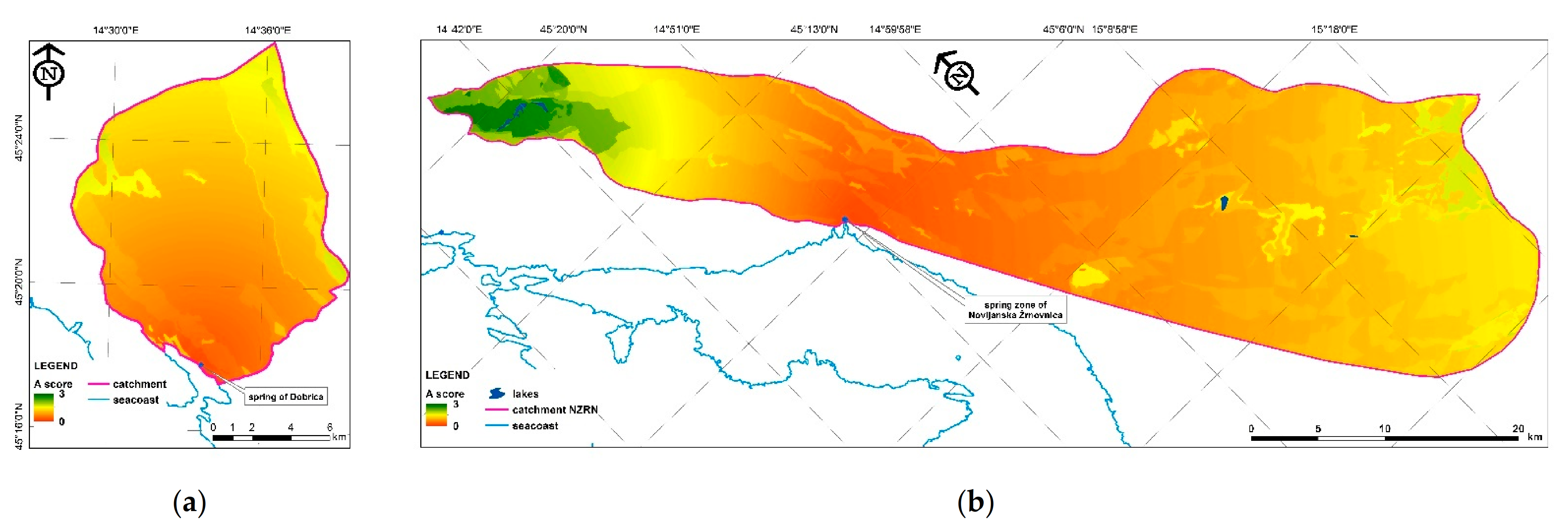

Conditions in the karst aquifer itself, important for the assessment of intrinsic vulnerability, are defined as the A factor, the overall impact of which is estimated through two layers of data: static conditions in karst aquifers are estimated with the Ahg subfactor (hydrogeological description) and dynamic conditions in karst aquifers are estimated with the Att subfactor (tracing tests).

In determining the Ahg subfactor values (hydrogeological description), static conditions in the karst aquifer are estimated based on available geological, lithological and hydrogeological data, while the basic criteria are the lithological composition of the rocks and the level of karstification. Other information that may also help in the assessment of this subfactor come from geomorphologic analysis, the results of speleological exploration, the results of well testing, spring hydrograph analysis, hydrochemical analysis and geophysical surveys.

Scoring of the Ahg subfactor is adapted to the overall methodology and represents a relative and immeasurable value. These values only indicate the fact that one hydrogeological formation, relatively speaking, is more or less vulnerable than another (

Figure 3).

In determining the Att subfactor values (tracing tests), dynamic conditions in the karst aquifer are estimated based on the results of tracing tests in the observed karst catchment area. Observed tracing tests have to be performed during the rain seasons when the groundwater flow velocities are the highest. Data can be obtained by analyzing the discrete apparent time values.

It is possible to obtain these values for each tracing test by processing and analyzing all relevant tracing tests—apparent groundwater velocities and distance of tracer injection and tracer appearance sites. Using GIS spatial analysis with suitable interpolation methods, it is possible to obtain from discrete apparent time values a continuous spatial distribution of tracing values relevant for an investigated karst catchment area.

It should be noted that the quality of spatial interpolation of tracing results will be more reliable the better the spatial distribution of the conducted tracing tests, which also results in more uniform values for tracing tests carried out in the same part of the catchment area.

Smaller values of the Att subfactor suggest better “connectivity” of a certain part of the catchment with the karst source or source zone, which actually increases the overall vulnerability of that part of catchment area compared to the rest of the area (

Figure 3).

When assessing the values of the Ahg and Att subfactors, it should be taken into account that, in relative time, these values are fixed, i.e., their potential variability cannot significantly effect the overall intrinsic vulnerability assessment of the karst system. This is important to note because karst aquifers can be very dynamic hydrogeological systems, as is the case of the karst area of the Dinarides in Croatia. In such conditions, some parts of the karst aquifers can change their hydrogeological function over time (e.g., permanent and temporary karst springs) and in space (e.g., fluctuations in the water table). However, due to the simplification of the model, these changes should be taken into account only when there are justifiable reasons or new knowledge (e.g., new hydrogeological studies, new tracing test results, etc.). In such cases, both subfactors should be re-evaluated and scored again and their impact on the overall intrinsic vulnerability of the karst system reassessed.

The A factor values (

A scores) are obtained by summing the

Ahg and

Att subfactors, as the effects of these two subfactors complement each other (Equation (5)):

Possible values are in the range of 0.2 to 3. Smaller values indicate the greater vulnerability of a karst system conditioned by greater karstification, potentially better permeability of layers and tracing test results that show better and faster connections with the karst spring. High values of the A factor indicate parts of the catchment area that are not directly related to karst springs, or parts of catchment areas for which the permeability is limited. These are very often areas made of non-carbonate rocks, in which shallow subsurface aquifers with limited spreading could be developed.

In preparing the final intrinsic vulnerability map with the KAVA method, unclassified A factor values should be used.

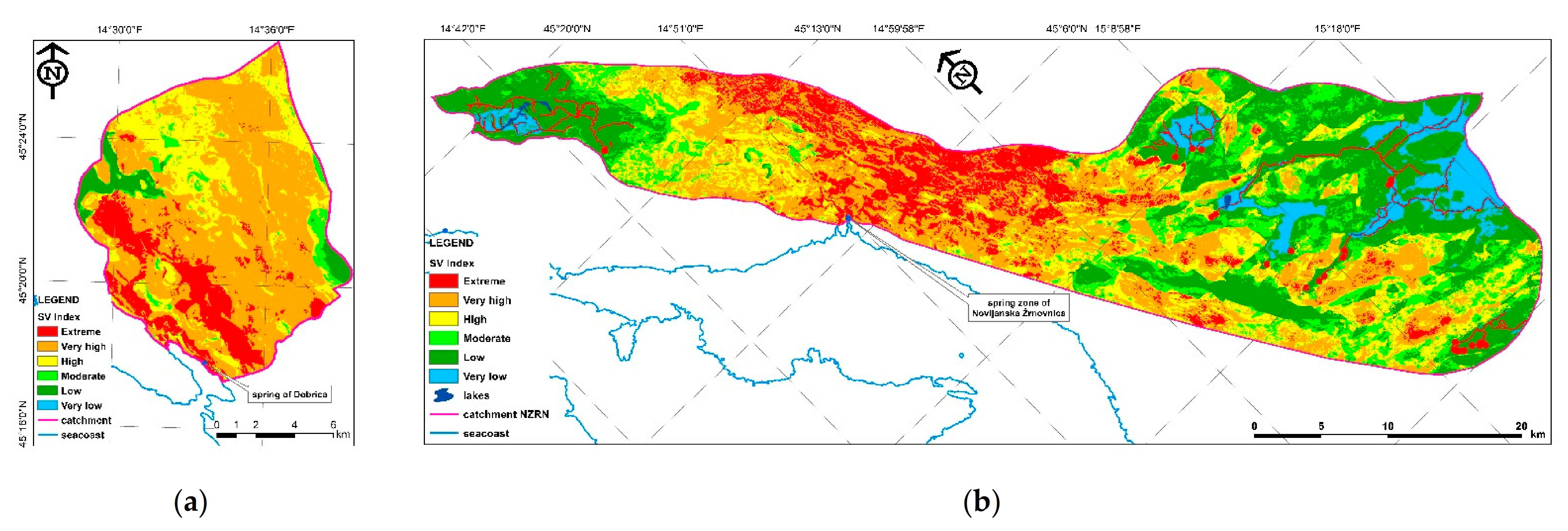

2.7. Vulnerability Indices

The overall results of the karst catchment analysis are two indices of vulnerability. The source vulnerability index (SV index) refers to the assessment of the intrinsic vulnerability of karst springs (Equation (6)), and the resource vulnerability index (RV index) refers to the assessment of the intrinsic vulnerability of karst aquifers (Equation (7)).

In calculations of both indices, a critical parameter is the A factor. Specifically, when assessing the intrinsic vulnerability of karst springs (source vulnerability), values of the total A factor related to the observed spring are used, since in this case the A factor takes into account the static and dynamic conditions in the karst system.

By separating the A factor into the two main subfactors (

Ahg and

Att) and taking into account only subfactor

Ahg, an estimation of the intrinsic vulnerability of the karst aquifer (resource vulnerability) can be obtained, because in this case the A factor considers only the static conditions in the karst aquifer.

Calculation of both indices is made in such a way that the scores obtained by calculation of each factor (O score, I score, A score) are summed altogether and multiplied by the score of the P factor (P score), which represents the external stress in the KAVA method. After that, the additional extraction of the most vulnerable parts in the catchment area (swallow holes, swallow hole zones and zones of sinking streams that gravitate to these swallow holes) should be undertaken in such a way that the SCA 1 parts of the catchment area automatically have a unique value of 0.1 points.

Finally, the SV index values range between 0.25 and 10.5, and the RV index values range between 0.25 and 7.5.

For the final intrinsic vulnerability map, the obtained values of these two indices are classified into six categories of vulnerability (

Table 1). The spatial distribution of the SV index is displayed in the form of a source vulnerability map and the spatial distribution of the RV index in the form of a resource vulnerability map.

4. Conclusions

The multiparameter KAVA methodology was developed as part of projects for the UNESCO-IHP in 2014 [

41,

44] and 2015 [

45] examining the intrinsic vulnerability of the Novljanska Žrnovnica karstic spring catchment area and the Bakar Bay catchment area, located at the northern part of the Croatian seacoast. Although Novljanska Žrnovnica is a typical catchment area of the Dinaric karst in which almost all the karst phenomena and forms could be found with the development of the KAVA method, it was necessary to test the method in another catchment with slightly different characteristics. For this purpose, the Bakar Bay catchment was selected, a smaller karst catchment area situated adjacent to the Novljanska Žrnovnica catchment area.

The verification of the KAVA methodology was carried out according to the existing KAVA methodology in the same way as the majority of the previous analyses on the Bakar Bay catchment area. In this way, initial vulnerability maps were obtained. By comparing the vulnerability maps and all subfactors and factors for both catchment areas, detailed multiparameter analysis of the obtained data was performed.

Recommendations for the management of groundwater can be divided into four categories: restrictions, active protection measures, remediation actions and dissemination.

Restrictions can be developed according to the corresponding vulnerability classes, primarily for the locating of new (potentially polluting) human activities. In the case of karst aquifers, the protection criteria can be specified in accordance with the vulnerability class determined by the RV index. In the case of karst springs or groundwater intakes, the protection criteria can be specified in accordance with the vulnerability class determined by the SV index.

Active protection measures may include frequent water quality monitoring in the very high and extreme vulnerability karst areas, if it is possible with the morphology of the terrain. They may also include actions to improve the situation of water, such as construction of public water supply and wastewater disposal systems, introduction of clean production, ecological farming and installation of tanks for hazardous and polluting substances with additional multiple protection.

Remediation actions primarily refer to existing human activities that may threaten the good condition of groundwater in a certain karst area. A necessary remediation action program may include a list of all pollutants in the karst area, a list of priority remediation procedures, etc.

Dissemination activities refer to public participation, at a certain scale; this is always welcome and there are very good reasons why such activities should be organized, especially at a local scale. Local public participation meetings could be held, organized either by the competent authority or by local water managers.

The KAVA method was developed because only a very small number of the methods previously developed can be used without significant limitations in determining the intrinsic vulnerability of karst aquifers, such as aquifers in the Dinaric karst. Due to the very similar characteristics of karst aquifers, this method can be used in the wider Mediterranean area as well as in Croatia, which was the intention of the UNESCO projects within which this method was developed.

The results of the vulnerability mapping can be used as a tool—as additional information—in complex hydrogeological research work in a particular catchment area and in groundwater protection projects.