1. Introduction

The smart city process needs to be anthropocentric; we must not see the smart city process solely as a technology implementation task, but as a reformation of public space to suit the needs of individual humans. Most importantly, we need to incorporate systematic and conceptual solutions that solve the causes of problems rather than just the consequences. At all times, we need to consider the human scale of all things [

1].

The importance of analyzing the current situation, data, and possibility of improvements were confirmed by Angelidou [

2] in her paper focusing on the development of smart cities. The author also mentioned that it is easy to be enticed by impressive visions of smart cities and pay attention to what is missing rather than utilizing amenities of the city. She also highlights the importance of selecting a few main areas that need to be improved as a matter of priority. Different locales have different priorities; for example in Amsterdam the focus was mostly on energy and open data, and in Rio de Janeiro, the focus was on security and transport. According to her research, including stakeholders is essential in order to create “morally balanced and socially aware smart city strategies”. Stakeholders can, for example, provide important information about the needs of the city or increase the public acceptance of projects. She also mentioned that smart cities can be developed through small-scale projects if they are a part of broader strategic plans anticipating synergies among them. These small projects are more user-friendly and increase the awareness and possibility of acceptance by citizens. A case study from Barcelona [

3] confirms the importance of cooperation of multiple subjects while planning a strategy (not only governance, but also other organizations and communities). The vision and goals should be shared with the most important stakeholders. As the city’s inhabitants, citizens should also be involved while the projects are being designed, implemented, and evaluated. In [

4], Angelidou, M. notes that stakeholders should share their needs with governments, and that it is important to include experts from various fields while planning smart city strategies and adapt the strategies to local contexts.

In another paper [

5], Angelidou, M. points out the importance of taking into account both technology (digital intelligence) and knowledge (smart intelligence) to help with the realization of smart cities and further urban development, which many strategies fail to do. According to her research, demand-driven solutions are more effective than supply-driven solutions in smart cities. A smart city strategy should try to meet the needs of citizens. She states that raising citizens awareness, improving their skills with technologies, and providing access to them is essential [

4].

Currently, there seems to be a vacuum of scientific findings in detailing how to cope with long distance strategy preparation under the influence of the COVID-19 crisis. However, some interesting research about the influence of the current crisis on mobility has been done. Researchers have suggested possible directions in urban and mobility planning based on lessons learned during the pandemic. The mode choice in many cities has changed during the pandemic. There was an increase in car use and decrease in traveling by public transport [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10].

Campisi et al. [

6] focused on the influence of COVID-19 on the resilience of sustainable mobility in Sicily. The authors used a questionnaire, undertaken in spring 2020, to compare the travel behavior of people before and during the pandemic. People liked the idea of using micro-mobility during the pandemic. According to the authors, this can be seen as useful information to create sustainable urban plans and a motivation for decision-makers who promote the use of walking, cycling, micro-mobility, and public transport. They also mentioned that bicycles should be an alternative, particularly in less densely populated parts of the towns, and that the space that was originally meant to be used for transit and the parking of cars can be used for cycling. There are many ways to repurpose parking spaces that occupy public space. Giving them back to people is only one variant.

Özden et al. [

8] reported similar findings. The authors used data by Apple Inc. (Cupertino, CA, USA) and Google Inc. (Menlo Park, CA, USA), which provided data such as driving and walking trends and daily location access trends from three time periods: before the pandemic, during temporary lockdowns, and normalization. They suggest turning the current crisis into an opportunity, by making strategic plans to improve the infrastructure for cyclists and pedestrians. People are using micro-mobility more than ever before, and the reduced demand for public transport is expected to remain low for some time (due to sanitary issues and fear of contamination). The authors also recommend improving the connectivity of transit stations and P+R (park and ride) lots to attain a proper level of the sustainability and resiliency of mobility.

As with other study, in a recent Italian paper (Barbarossa, L.) [

7], the improvement of cycling and walking infrastructure is also recommended. The authors mention that due to the need of social distancing, public transport systems are not able to run at full capacity. Thus, public transport might not be in competition with private cars. However, increased usage of private cars can lead to an increase in air pollution. In their research, they found that many cities around the world are adopting the following measures: widening pavements that are close to parks, schools, and shops, removing motor traffic from residential areas, and building safe cycling routes to offices, schools, and close to main roads (by closing unnecessary roads and squares to motorized traffic). All of this is to support sustainable mobility (cycling and walking). As an example, the article states that Paris plans to make amenities reachable within a 15 min non-motorized trip for its residents; London plans to build new cycling and walking routes next to major roads; and Mexico City plans to build new bike paths in order to encourage people to stay away from public transport.

Combs et al. [

11] noticed worldwide measurements such as carving out roadway space for pedestrian and cyclists or reducing speed limits. Basu et al. [

9] added that a multi-modal approach will be needed to ensure affordable and sustainable urban mobility.

In the paper from González-Sánchez et al. [

12], recommendations for making effective policy decisions based on SWOT analysis (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats) to address the situation after the pandemic were suggested. They focused on sustainable mobility and gender equality. In total, they created 16 strategies. For our paper, the most relevant seem to be facilitating public transport with bicycles or personal mobility vehicles, improving the safety of public transport and restoring confidence, redistribution of public space to prefer active mobility, and lowering the number of lanes for private cars, speed and parking.

In summary, scientists from various regions recommend supporting micro-mobility (bicycles, scooters, motorcycles) and walking infrastructure in order to offer alternative transportation modes to cars, while enabling the maintaining of social distancing in the future. This provides an interesting view over some troublesome areas, which are described below as parking and public transport. While it is necessary to still focus on the overall improvement and changed approach to these areas, it is also necessary to consider the recent findings and always support micro-mobility.

As described above, many cities currently face the need to redevelop their infrastructure to be able to compete globally. To reach that, it is necessary to maintain or enhance the quality of life by improving city services and resources [

13]. The city of Chișinău is no exception.

While the project itself was aimed at analysis of the current state of transport and mobility in Chișinău city, and after that, recommendation of particular measures, the paper shall explore the chosen approach, most important findings and their respective measures, and the added value of cooperation. All steps of document creation need to be discussed, so that the main goal of the paper can be reached.

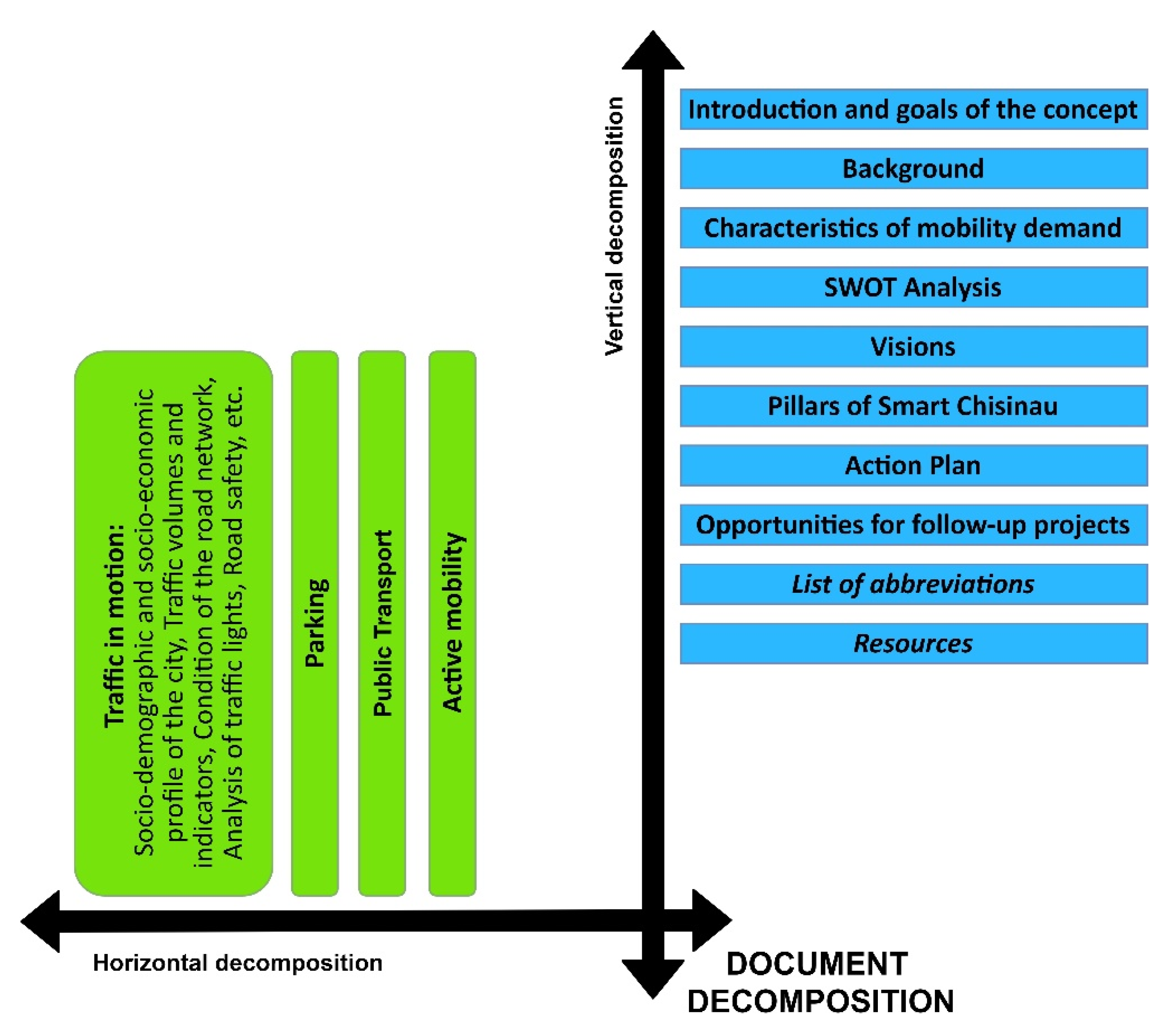

To see to the specific needs of the city of Chișinău (or rather, the Republic of Moldova) four main areas of expertise with respect to mobility have been defined. These have been visualized in the horizontal decomposition in the figure below (

Figure 1): Traffic in motion, Parking, Public transport, and Active mobility (walking, cycling, other means of micro-mobility). The municipality gives the greatest heed to parking and public transport, and rightfully so. Even though the document formally distinguishes four main areas of expertise, there always needs to be a certain level of overlap into other fields (such as urbanism, healthcare/emergency services, etc.). The vertical decomposition follows frequently used and agreed upon structures of strategic documents (the intention was to define problems through thorough analysis and communication) and propose solutions that follow a simple vision.

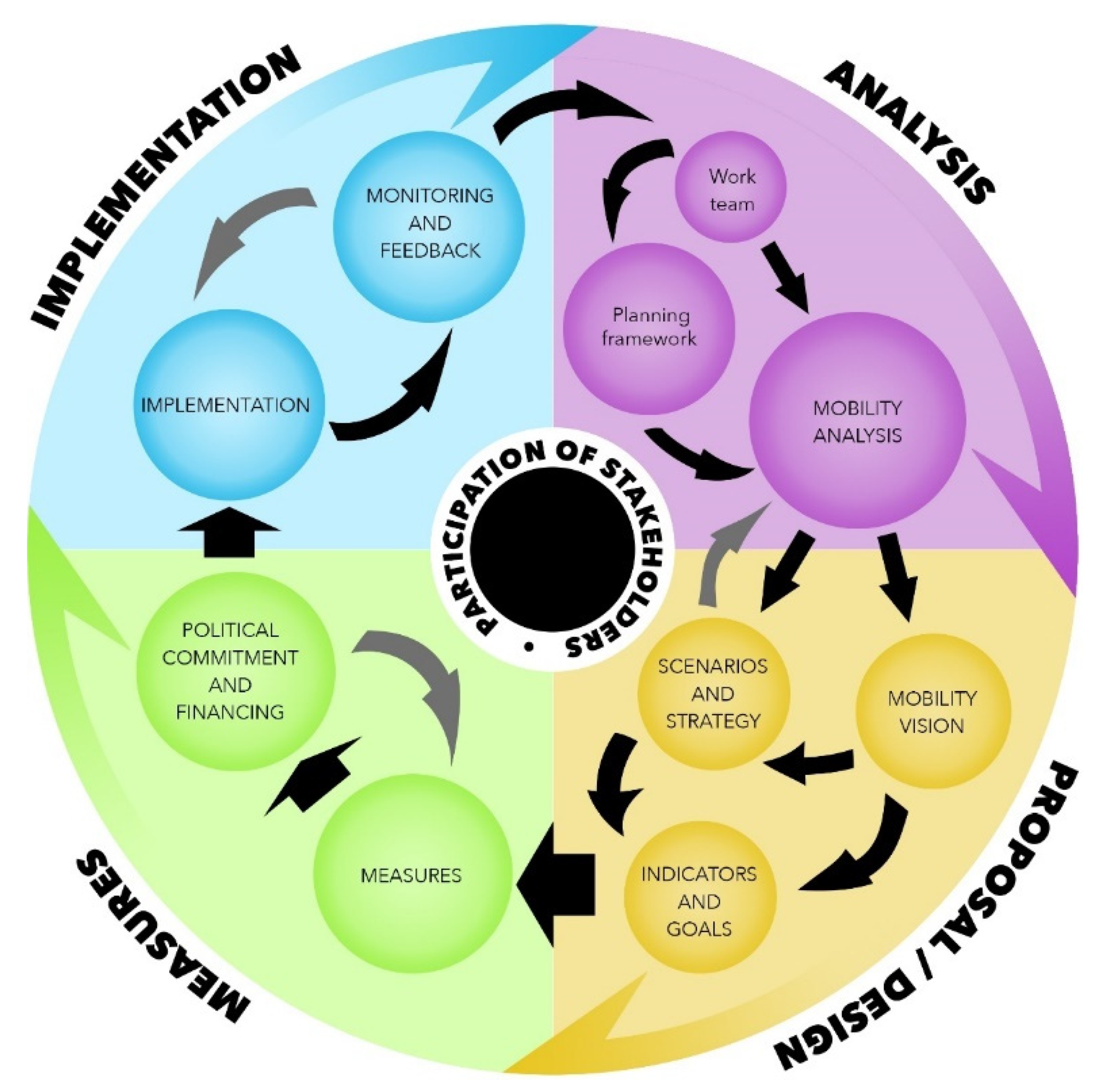

Perhaps the most important premise to mention is that the effort does not end with this project. Moreover, the work is not finished by the completion of the document. While in theory this might seem rather obvious, in many cases, municipalities tend to cease their efforts after a document has been created, even though this is when the actual work starts. With no follow-up, there is no reason to invest energy into strategic document projects. The working team bases their estimates on the idea of a cyclic approach to city planning, as shown in

Figure 2. In this approach, the implementation phase is both the end of the project and the beginning. Any public project that hopes to be successful must not fail to include all necessary stakeholders.

The goal of the article is to assess whether it is possible to create a well-received strategic document (in this case, a smart mobility strategy) while the effects of the global pandemic caused by COVID-19 change the known factors and force the team to work from abroad, rendering them unable to visit the site. Initially, the project was to include multiple trips to the Republic of Moldova (the teams is from Czech Republic—part of a UNDP project aimed at the transfer of knowledge). However, due to the effect of the above-mentioned global crisis, it was not possible to visit the country. The only means available were online meetings and communication and the analysis of available data. Unsupervised, no other measurements and surveys could take place. Fortunately, the city already had several interesting datasets.

Throughout the work on the strategic document, the team devoted significant amounts of energy on researching the matter of the degrading condition effects to the project. However, no scientific articles or other papers were found which could help the teams work through the problems that arose. Therefore, the team was forced to create their own methodological approach on how to deal with such conditions. Everything is based on a straightforward hypothesis.

Procedure: to counter the effect of the global crisis (pandemic-related measures of COVID-19), such as forced work from abroad and the inability to physically visit the site, existing data sources were chosen to be a determining factor in weakness identification and section prioritization.

Hypothesis 1. Using data from traffic flow volumes provided by the police, the data of accident rates, data about queue creation and communication with stakeholders are enough to properly identify priority areas of expertise within Smart Mobility.

To confirm or disprove this hypothesis, this article will cover how the data and other sources of information were analyzed, and what was found after additional communication with the city and stakeholders. There was also an additional hypothesis made by the team when working on the initial hypothesis. The second hypothesis will be referred to later in this work as a Hypothesis 2.

Hypothesis 2. The city of Chișinău is made for cars, not for the people, lacking an anthropocentric approach.

Proving this hypothesis is possible through the same approach as proving the first hypothesis, with data analysis.

2. Methods

The structure and approach chosen for this project were the same as in numerous strategic documents throughout Europe and Czech Republic to further the transfer of knowledge (an important aspect of the cooperation). Cooperation with other cities and experience and knowledge exchange is a practice in smart city strategies of existing cities with international characteristics [

4].

The whole chosen process is systematic in its nature and can be summarized in several steps, as follows:

- -

Communication with stakeholders;

- -

Detailed analysis of available data;

- -

Defining vision and strategic goals;

- -

Describing individual measures.

The fundamental idea is to define the problem based on thorough communication and detailed analysis, subsequently agreeing on a common goal to support (vision) and finally to reach the goal through individual measures (sorted into strategic goals that follow similar division as the analytical part does). The approach has firm roots in new European Sustainable Urban Mobility Plan methodology—aka SUMP 2.0 [

15] (CIVITAS SUMPs-Up, 2020).

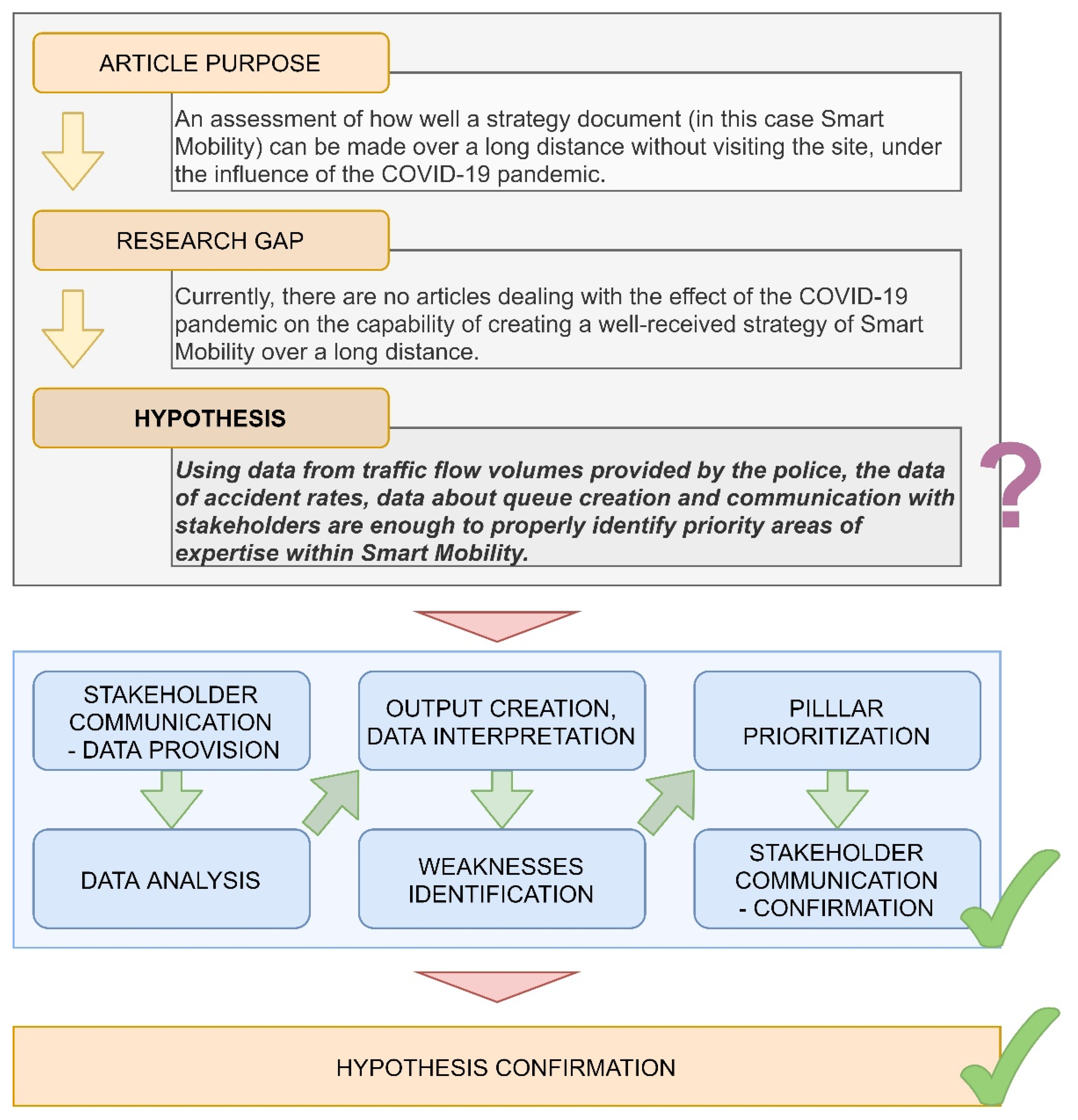

For the chosen approach, or methodology, to counter the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, see

Figure 3. There are two main changes to be made: (i) the communication is needed to be given greater heed, because the visit and personal discussion were canceled; (ii) because no additional data could be collected by the team (and no surveys could take place), it was necessary to carefully chose which data to work with.

The reasoning behind this methodology was based on the size of the city and the current situation. Conducting any large-scale survey over a long distance was out of the scope and nullified. A city of this magnitude needed to be described through hard data combined with clear communication.

The first step was the communication with stakeholders (See

Section 2.1), then the data analysis was performed (

Section 2.2), creating heatmaps of road infrastructure, accidents, and traffic flows volumes. The research team expected that by watching traffic flow and traffic jams, the most problematic locations will be found. Afterwards, a summary of weaknesses was conducted through the SWOT analysis. This was followed by the creation of a vision (

Section 2.3) and suggestion of measures to address discovered problems (

Section 2.4). Again, the findings needed to be properly communicated with the stakeholders and the city. This step would confirm or reject the hypothesis.

2.1. Communication with Stakeholders

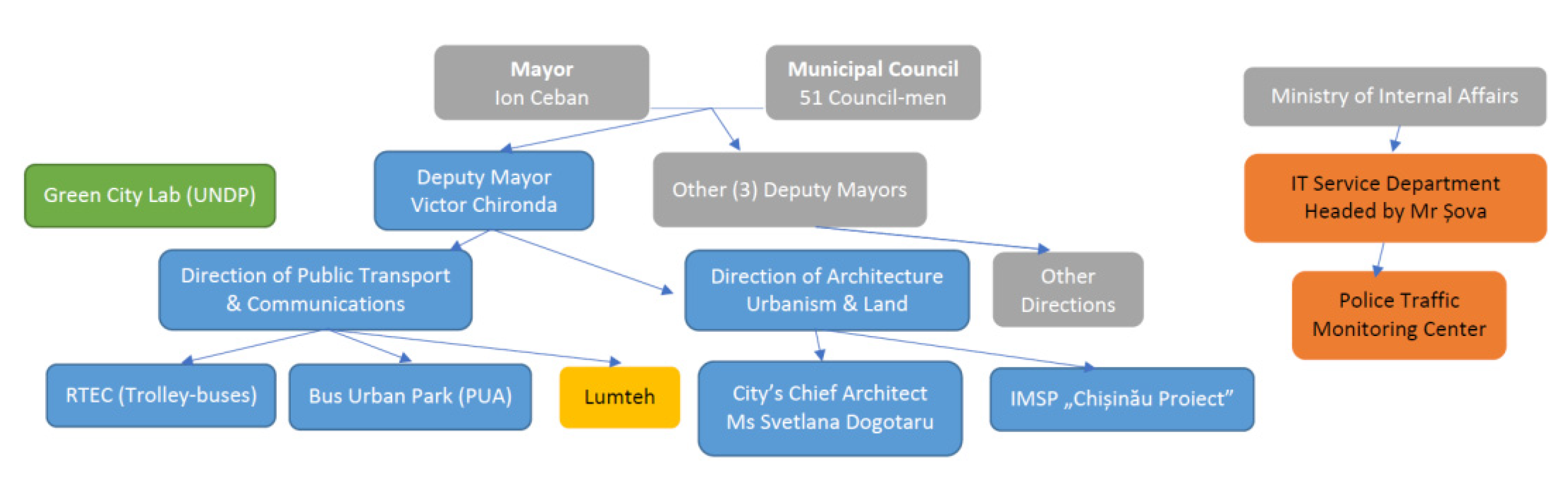

Proper communication is the very basis of proper understanding of a subject at hand. The authors of the document were from a foreign country and initial visits were made impossible due to COVID-19 related restrictions; therefore, a proper mode of communication needed to be arranged. In the figure below (

Figure 4), a map of stakeholders can be seen. These are the same entities and institutions that would be consulted in person; however, due to the above-mentioned difficulties, these had to be “visited” in a virtual environment. To compensate for the long-distance communication and diminish the impact of not being able to visit the site personally, the communication was made more frequent and longer to cover all important aspects. This was all made possible by the unyielding effort of the teams in the Czech Republic and in the Republic of Moldova. Through this thorough communication, all necessary topics were covered.

2.2. Data Analysis

The first step of analysis was completed through analytical work with map data. This step can be called the mapping phase. In this case, the most prominent and useful data source was OpenStreetMap data available in GIS (Geographic Information System) formats and applications. This gave the project, or rather the city, a tangible scope for the team to focus on. It allowed the authors to experience the spatial dimensions and understand what the terrain and urbanistic structure looked like and how they might affect the day-to-day life of residents and visitors. In

Figure 5, there is the visualization of the road infrastructure in the city of Chișinău. The location of various points of interest (such as frequent traffic jams, data collectors, etc.) were then added through communication with stakeholders.

After the city was mapped, then came the collection of other data sources (e.g., socio-demographic and socio-economic data, heat-maps from Strava [

16], data collection points, data of road accidents, etc.). The visualization of heat-maps accidents can be found in

Figure 6. All the datasets were provided by the municipality, municipality institutions, or by stakeholders.

Traffic flow volume data proved to be the most interesting (analysis-wise), because it provided a number of opportunities and ways to analyze the traffic in Chișinău utilizing this data. The possible visualization is displayed in the figures below (

Figure 7 and

Figure 8).

Combining the data with the location of frequent traffic jams (based on local experience) and the utilization of Greenshield’s model—the mathematical relationship between velocity, traffic density and traffic flow volumes [

18,

19]—allowed the team to properly assess the state of road traffic in the city. The cumulation of traffic jams, parts of the infrastructure with high traffic flow volumes, and the geometrical properties of the infrastructure itself provided enough insight to confirm Hypothesis 2 of a city made mostly for cars and not people (this being one of the fundamental errors that the vast majority of cities made in the past and are only now addressing).

2.3. Vision

The vision determines the main direction, or rather, the destination, that the political representation of the city wishes to reach in its long-term development and urban planning. It sets boundaries for individual measures and gives context.

2.4. Measures

The measures were divided among strategic goals or subchapters, all in support of the main vision. Although all measures (and all strategic goals) should be equally important in the long-term planning, it is understandable that there is a certain level of priority in short-term planning. For instance, the two main areas of expertise that are discussed in this paper (parking and public transport) are the imminent threats to sustainable mobility, because they are believed to be the core problems to the population.

3. Analysis of Existing Problems in the City of Chișinău

This chapter describes problems found in the city of Chișinău during the project. While there are several insufficiencies and possible problems, two areas of expertise stand out as the greatest opportunities for change and improvement. These two areas are parking and public transport.

3.1. Parking

The main problem with parking in the city of Chișinău is that it is free and unregulated. It is even possible to park on the sidewalk and in the green areas. This, in addition to problems with the public transport (further described in the next chapter), leads to massive use of cars which has environmental and other consequences.

However, the problem is more robust. The car user is seen as the obvious customer when planning further development. Individuals are starting to notice that there are simply too many cars and too little space. Dedicated parking spaces are outdated and inefficient, meaning no one can always have a guaranteed parking spot, requiring parking to be severely regulated and digitized.

It was discovered that the demand for short-term parking (up to 150 min) is about ten-fold higher than the demand for longer parking [

20]. This also poses a problem because there are fewer parking spaces left for local inhabitants who encounter difficulties finding a parking spot. It is apparent that many cars are parked illegally, for example on the pavement, which further degrades the public space and restricts pedestrian movement.

Another problem, in this case with solving the parking issues in the city, is the lack of norms. Moldovan norms on road construction and traffic regulation do not mention the dimensions of a parking space. This makes it harder for the experts to solve these problems. There are no given legislative requirements for a parking space; therefore, any design could be denied if the concept of parking regulation is disputed.

3.2. Public Transport

The main problem of the public transport is that there is no integration. There are, in fact, three separate transport systems. One of them is railway transport, the second one is transport organized by a municipal company, which consists of buses and trolleybuses, and the third one is minibus transport (marshrutkas).

Although Chișinău has a good accessibility of public transport stops, and 90% of the area is theoretically in quite a short walking distance to a public transport stop (250 m in the city center and 500 m in other parts of the city), actual walking distances can be longer. This can be due to long intervals at some stops. The situation induced is that it may actually be faster for the passenger to walk to a farther stop that has more frequent public transport service.

The trolleybus network measures 285 km, which makes it one of the densest trolleybus networks in the world (in relation to the size of the city). However, the infrastructure is outdated. Although the investments in the new vehicles have started, about one-third of the vehicles are over the age of ten years. In 2019, the trolleybuses transported about 17.4 million passengers on 31 lines.

The bus network consists of 23 bus lines, of which 18 are suburban. Both buses and trolleybuses are available in both standard and articulated versions. The buses carried about 145 million passengers in 2019, which is about 400,000 passengers per day. Given that there are 127 bus vehicles in circulation in Chișinău, this means every bus carries 3150 passengers per day on average, which is about 50 journeys per day, at full capacity, every day. The vehicles are generally very crowded. The bus vehicle fleet is quite obsolete. and the average age of the vehicles is 14 years.

Apart from the buses and trolleybuses, there are also 43 lines (of which 23 are suburban) of minibuses (marshrutkas) with 743 vehicles in service. These vehicles are even older than the buses; the average age of the minibuses is 18.5 years. With a capacity of 15 passengers per vehicle, it is questionable whether this transport mode is suitable in a large city, such as Chișinău. It may be needed to transform this system to a more suitable mode of transport in the future.

The city of Chișinău has over 500,000 inhabitants and the share of public transport in transport performance is estimated to be about 60%; therefore, it is recommended for a tram or railway system to be the backbone of public transport. The existing railway system appears to be suitable for this purpose, it just needs to be integrated in the city’s public transport system.

Additional problems with the public transport lie in punctuality, the regularity of service, and the fare system. Every line has its own interval of service, which is based on both the demand for transport and cruising time of the line. Thus, every line has its own intervals, independent of other lines. This leads to other various problems, especially for the passengers. The punctuality of the public transport vehicles is monitored using the GPS system, however there is no set standard for transport punctuality. The punctuality is affected by the poor technical conditions of both the vehicle fleet and the infrastructure. The fare is combined within the transport system, based on distance traveled and number of journeys. The price of single ride tickets is so low that people are not encouraged to buy a subscription ticket; currently, only about 1.5% of riders use these.

All data above are taken from the analytical part of the Smart Transport and Mobility Strategy and Action Plan for Chișinău City [

17].

4. Examples of Using the Methods/Measures

Not only are parking and public transport the most prominent among the areas of expertise, but these also need to be seen as two systems that work best when they co-exist symbiotically. These should be extensions of one another and should not be seen as competing systems [

21]. An important aspect of determining whether the chosen methodology for specifying the priority areas was to not only discuss this with the stakeholders, but also to choose suitable measures, that could counter the problems and identifying these measures (at least partially) could be implemented within a shorter timeframe (within five years).

4.1. Parking

The problem lies in how the people understand (or rather misunderstand) the place of the car in public space; therefore, adding extra capacity will not solve the problem, it would simply postpone it. Additional capacity is only a panacea when accompanied by additional steps.

The solution itself can be simplified into three parts: zone creation (including pricing policy), digitization, and P+R utilization. The creation of zones (see

Figure 9) gives the police and administration a simple-to-define and simple-to-use tool for regulation. It also enables simple city-wide changes in pricing policy (benefiting the residents and restricting visitors in the center). The change from non-regulated free parking to city-wide zones will be the most difficult change to accept if not communicated properly. Digitization allows for simple management, enforcement and user experience (it might seem overly regulated at first, but in the end, this benefits both the city and the citizens). Lastly, P+R parking (if placed logically) will allow commuters to leave their cars on the edge of the city and transfer to public transport (this creates the greatest cooperation between the two systems). The unifying component is proper parking management, which can be reached through several measures, that are not necessarily budgetarily intense.

A rough summary can be that people unfortunately cannot park wherever and whenever they like; they need to understand the restrictions that come with limited space. The public space should belong to the people, not to their cars.

4.2. Public Transport

In order to create an efficient transport system, to solve the problems of all its individual components and combine them into one coordinated system, an integrated transport system (ITS) is needed. The integration process consists of the appointment of an ITS coordinator who will manage and fund the public transport service, while the transport companies will only maintain the public transport operation. The coordinator will also elaborate the ITS quality standards and methodology of their implementation and the strategy documents. ITS also includes the construction and modernization of railway infrastructure, together with the construction of multimodal changes near the most important train stops.

In order to make the system work as intended, it is needed to include all modes of transport into the system, including trains, and coordinate them. Including the trains in the system brings a significant increase in transport capacity and cruising speed, which helps the public transport compete against individual car transport.

The next improvement should be the optimization of inter-stop distances in the public transport network. Truncated distances cause vehicles to stop too often, and therefore slow down the public transport. On the other hand, extended inter-stop distances cause lengthened walking distances; therefore, some people may opt for using a car instead of the public transport. Another means of raising the cruising speed of the public transport is the prioritization or preference of public transport. That means elaborating a strategy for public transport prioritization development with emphasis on comprehensive transport solutions.

An integrated transport system also includes quality control, i.e., standards for the punctuality of operation. These should be developed and include an acceptable deviation from the timetable by the level of demanding character. For example, the integrated transport system in Prague demands that at least 80% of the tram connections are delayed, at most, by 3 min [

23]. Deviations from the timetable should be continuously monitored and analyzed.

The final part of the integrated transport system is the fare system. The fare should be uniform, based on the number of stops, on distance, or a combination of these, regardless of carrier or transport mode used. One ticket should be valid in all means of transport of all carriers. All tickets, even short-term ones, should be transferable. There should be emphasis on subscription time fares, which are the best motivators for using public transport. This all will massively increase the motivation of people to use public transport. Furthermore, the fares should be gradually increasing in order to cover around 25% of the operating costs.

5. Discussion

The presented procedure described in this article fully respects methodological approaches such as the Newcastle City Council Smart City Strategy 2017–2021 (Australia) [

24]. However, unlike other methodologies, it differs in that it pays close attention to the analytical part and is able to adapt to the specifics of transport planning in each European city. The procedure is adapted to local conditions (especially as regards the delimitation of the territory, preparation management structures and monitored data, etc.) and emphasizes the local context. It is also well in line with the latest utilized approaches in the smart city, such as properly defined ontology in system hierarchy, the utilization of agent-based systems, etc. [

21,

25,

26,

27], or more abstract smart city approaches, such as seeing the information system and its similarities to quantum physics [

28].

In this article, the main finding is based in the experience of working on a project heavily influenced by the current global pandemic crisis while working from abroad. The lack of some data, lack of on-site survey of the working team, and having to conduct all interviews and communication solely through the digital environment have all put the team through a test of how possible it is to reach the correct conclusion about the current state of transport and mobility. While the project did provide a challenge for the team, in respect to suboptimal conditions, the experience was, in truth, extremely important for future projects, should some form of restrictions remain for an extended period. There is little to no possibility to conduct such a project differently with our current knowledge base.

Finding no relevant research on this particular topic was a disappointment, because there is no comparison for different approaches to such a task. The influences of the global pandemic crisis, however, have been subjected to multiple research projects, that did provide a lot of insight for the authors. For instance, the current dissatisfaction and overall mistrust of public transport, that should, under normal circumstances, provide a core transport system to any major city, does point towards micro-mobility-oriented transportation systems. Hopefully, trust in the public transport will slowly return, and perhaps this will be accompanied by major transformations in inter-modality and incorporation of the first and last mile solutions into the current public transport systems [

17,

22].

The use of digital technologies to communicate have taken hold in our society at the beginning of 2020, due to COVID-19, and made their way into almost all areas of expertise, to include everyday life. Based on the experience from this project, it is likely that a considerable percentage of foreign cooperation will move to the digital environment. Whether this is good or bad will be revealed with time.

There is a substantial difference in culture and history between the Czech Republic and the Republic of Moldova; as the data analysis showed, there is still prevailing love for car ownership in the Republic of Moldova—proving the hypothesis (the initial hypothesis, defined by the team for the project) [

17]. This is now beginning to change in Czech Republic. However, there are also some similarities (it can be difficult to follow well thought-through strategies if the ever-changing political representation cannot provide “quick win” solutions along with the long-term planning, because the voters usually do not see that deep into city planning. Just like the Czech Republic has a lot to gain from its neighbors, Germany and Austria, in terms of sustainable mobility, there is a lot of potential for the Republic of Moldova to draw from the same experience from the Czech Republic (because some of the problems Moldova is facing right now, the Czech Republic has faced in the past as well).

Overall, most research focuses on the direct impact of the crisis to mobility in general. While the lack of research directed at the topic at hand provided no further insights, the relevant research on the impact to the mobility as a whole did put things into perspective and was quite beneficial in respect to having a broader understanding of the influence of the global pandemic. It did not help the team with finding out how it affected the creation of strategic documents. In this project, perhaps the most interesting thing is that the team managed to create a very precise analysis of the current state with no direct contact with the city.

It is necessary to point out that the smart city and smart mobility, etc., should not be considered solely for bigger cities (capital cities or other regional cities with hundreds of thousands or even millions of citizens); it should be possible to utilize basic findings even for smaller cities and villages. This research, however, focuses on an experience based on a project for the capital city of the Republic of Moldova, the city of Chișinău (around 640,000 citizens). While the findings should be relevant for similar cities, it is doubtful that it can be used for any city, town, or village, regardless of the size. Further research should be conducted that considers differently sized cities, possibly enabling a meta-analysis.

Further research for multiple areas of expertise, different environments, and different sizes of cities should provide enough data for meta-analysis, helping to provide more certainty into how to create a strategy under the influence of a global pandemic while working from abroad. Some experiences are not transferable, and one study does not cover all possibilities. Some experiences, however, are transferable, such as those regarding communications with officials. While the current crisis may (hopefully) end soon, others might follow in the future, and we should be prepared.

6. Conclusions and Recommendation

To conclude, the first hypothesis for this article was proved; the analyzed data allowed the team to specify what should be a priority. This was later confirmed by the municipality to be indeed the case. Data allowed for problem formulation, that pointed to two areas of expertise: parking and public transport [

17,

22]. Not only are parking and public transport seen by the municipality as most important, but they are also the most challenging to truly solve, because some steps can involve greater opposition from users if not communicated properly. They do, however, not necessarily need to be expensive, as opposed to some costly infrastructural changes. Most of the measures in these two areas can be described as organizational. Although the hypothesis was proved, it should be emphasized that multiple visits to the site should be always included in such projects, if the situation allows. However, if the situation proves more challenging, it certainly is possible to conduct the work virtually, in the sense of not being present.

The hardest challenge to overcome was indeed the limitations of the crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. However, a quick replanning took place, and the result was very promising in the end. The outputs of the analysis and prioritization proved to be most beneficial to the municipality, because they are now able to be drawn from the findings. The premise of the project has always been foreign cooperation. Therefore, it was always known that most of the work would be conducted from abroad with limited journeys to the city. An advantage can be seen in 100% of work being done from abroad, that every key person was very keen and prepared to react and offer any assistance. Additionally, in future, expenses can be cut by removing the travel fees, because everyone was very aware of what inactivity in these worsened conditions could bring. In contrast, not seeing the city first-hand could have created a crooked idea of what problems the city is actually facing (this is the reason why stakeholder confirmation was necessary).

The proactive approach from the city representatives was a refreshing change and was one of the main driving forces of this project, combined with the increased flexibility needed from the authors. Everyone needed to deal with the changing circumstances of COVID-19, and the way everything was managed allowed for the completion of this document and important experience for both sides. The approach is unique because of COVID-19; every single step of the creation of the presented strategy (such as communication with stakeholders or the analysis of the current state), was done at a distance, because the research team could not travel to Chișinău due to the global pandemic.

The most important thing to do now is to never stop. In order to maintain pace with other fast-growing cities, the updating of transportation networks should never stop. Otherwise, the city will not attract people and ideas [

29].

This document only provides a plan. Immediate implementation of short-term plans and further development need to keep this idea alive. Not adhering to strategic documents seems to be the weakness in Czech Republic, at times. Only time will tell if the city of Chișinău can work well enough with what they attained from the project. It is also important to not be afraid to update the document if necessary. Provided that the end-goal is visible and tangible, the journey can evolve. The upcoming months after the delivery of the design part to the city of Chișinău (aimed at implementation) should provide opportunity for the team to visit the city and see everything first-hand (survey the city). The most important aspect of these visits should be assessment, and whether these visits change the opinion of the team on how they assessed the city problems from a long-distance with the initial analysis. In other words, it provides an opportunity to compare long-distance work and first-hand experience on the same city and the same project.