Sustainability Practices in Hospitality: Case Study of a Luxury Hotel in Arrábida Natural Park

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Sustainability in the Hotel Sector

2.2. Environmental and Social Sustainability Practices

2.3. Motivations for Sustainability Practices

2.4. Benefits of Implementing Sustainability Practices

2.5. Sustainability from a Customer Perspective

2.6. Sustainability Practices and Performance

3. Methodology

4. Findings

4.1. Environmental Sustainability Practices

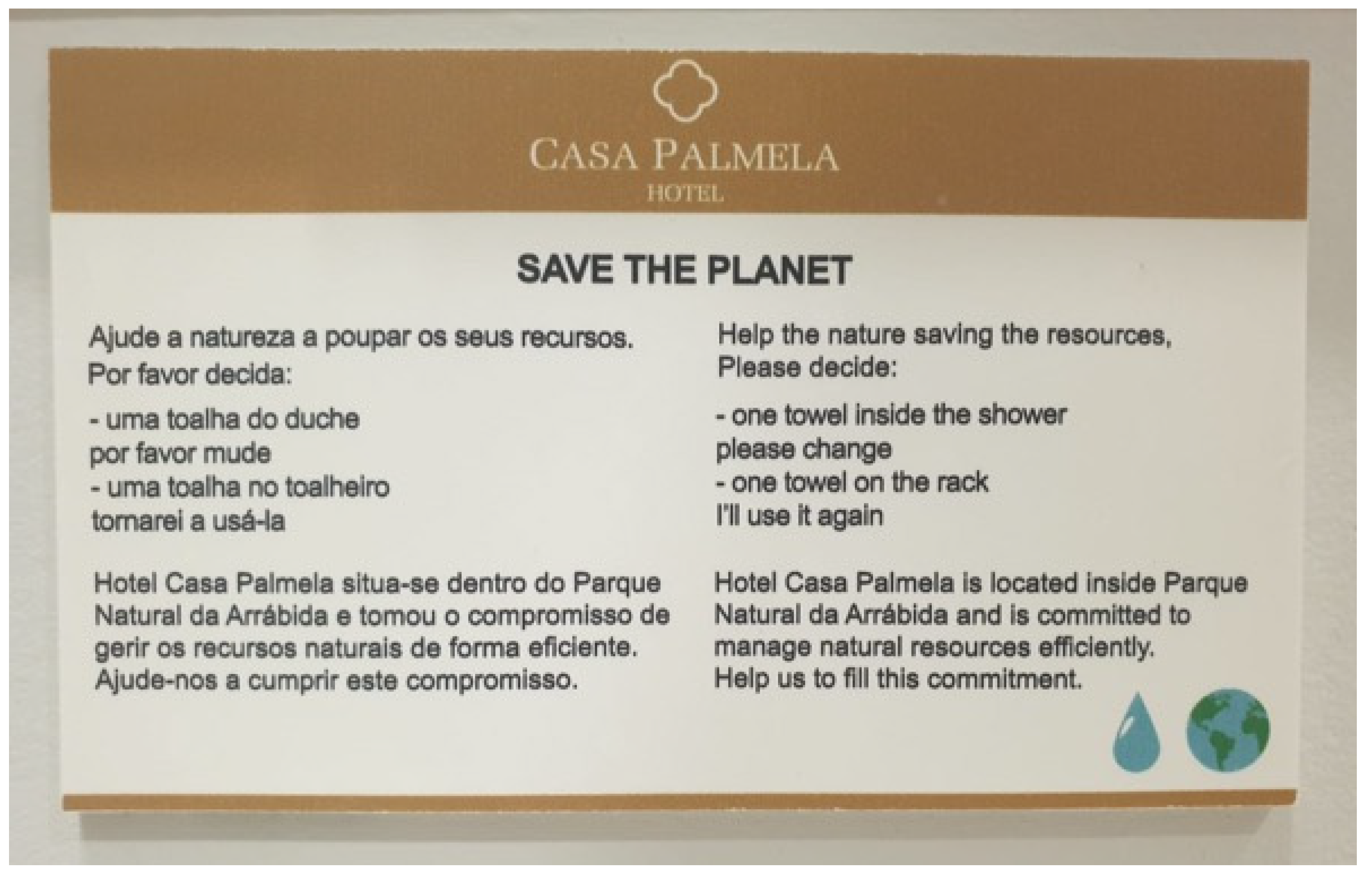

4.1.1. Practices for Reducing Water Consumption

4.1.2. Energy Reduction Practices

4.1.3. Waste Separation

4.1.4. Food Leftovers

4.1.5. Ecological Products

4.1.6. Prevention of CO2 Emissions

4.1.7. Laundry

4.2. Raising Customers’ Awareness of Environmental Issues

4.3. Social Sustainability Practices

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Managerial Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Data collection technique | Contribuition |

| Semi-structured interview and emails | Understanding the environmental and social practices adopted by the hotel, the management’s perception of the benefits and results from their adoption, how the hotel contributes to customers’ awareness of environmental issues, what specific environmental sustainability practices have had to be adopted by the hotel due to the fact that it is located in a natural park. |

| Direct observation (visit the hotel) | Observation of the various practices implemented by the hotel and taking photographs to prove their existence. |

| Document analysis (Hotel’s website, websites with online reviews, reports with energy and water consumption, permit granted by the Instituto de Conservação da Natureza e Floresta (ICNF), booklets) | Understanding whether the clients in their reviews mentioned any dissatisfaction with the implementation of environmental management practices. Confirm the results obtained in terms of cost reduction. Understanding what specific environmental sustainability practices have had to be adopted by the hotel due to the fact that it is located in a natural park. Understanding how the Hotel’s website promotes environmental campaigns. Understanding how the hotel communicates its environmental policy to customers and raises customers’ awareness of environmental issues. |

Appendix B

- (1)

- I would like to know if your hotel Casa de Palmela has any corporate social responsibility policies? Or any environmental policies?

- (2)

- To what extent do you consider that improving social responsibility and reducing environmental impacts is associated with the hotel’s culture?

- (3)

- Is improving social responsibility and reducing environmental impacts part of the hotel’s strategic planning?

- (4)

- Was an environmental impact study carried out before the restructuring? What is the reason for this study having been carried out?

- (5)

- Have employees had any training on environmental and social sustainability practices?

- (6)

- In your opinion, do you think that clients value the implementation of environmental sustainability practices? Or social sustainability practices? Or on the contrary, are they resistant to the changes implemented?

- (7)

- In your opinion, how does the Casa de Palmela differentiate itself from its competitors?

- (1)

- Does the hotel have any environmental system certification? If yes, when did you obtain it? What is the main reason for seeking environmental certification of the hotel establishment?

- (2)

- What specific environmental sustainability practices have had to be adopted due to the fact that the hotel is located in a natural park?

- (3)

- What environmental sustainability practices have been adopted since the hotel began operating?

- -

- Practices to reduce water consumption. If yes, how?

- -

- Practices to reduce energy consumption. If yes, how?

- -

- Practices to purchase more environmentally friendly cleaning products. If yes, how?

- -

- Practices for managing food waste. If yes, how?

- -

- Practices to avoid or reduce the waste of fresh products. If yes, how?

- -

- Waste separation practices. If yes, how?

- -

- Practices to promote environmental information (education) to guests. If yes, how?

- -

- Does your hotel establishment have an environmental management policy that promotes the adoption of environmental practices with suppliers? If yes, what actions have been taken (reduction of plastic packaging, smaller quantities, fewer deliveries, etc.)? If yes, how?

- (1)

- What practices has the hotel implemented to promote conscious consumption?

- (2)

- How does the hotel manage seasonal fluctuations in employee needs? (Are they transferred to other units, assigned other duties, hire temporary workers for peak season, etc.?)

- (3)

- Do you try to hire employees from the community where the hotel is located?

- (4)

- What is the hotel’s hiring policy in terms of gender?

- (5)

- What is the hotel’s involvement with local communities (contribution to the local economy, purchase of products for hotel consumption, handicraft, etc.)?

- (6)

- Are employees involved/informed in changes made at strategy level? How are they involved (e.g., meetings, email)?

- (7)

- Does the hotel encourage its employees to make more conscious choices in relation to consumption, health, community, and planet? How?

- (8)

- Does the hotel have an improvement suggestion program for employees? If yes, in your opinion, do you think that this program has led to an improvement in employee satisfaction? Did any of the proposals made by the employees refer to improvements in environmental management? Or at the level of social responsibility? Were these improvement proposals implemented?

- (9)

- In the hotel’s marketing campaigns are environmental campaigns promoted?

- (1)

- What are the environmental performance indicators that your hotel evaluates annually?

- (2)

- Does your hotel set targets (annual, quarterly, etc.) to improve these indicators?

- (3)

- In your opinion, do you think that the adoption of environmental management practices contributes to improving the image of the hotel? And social practices?

- (4)

- Have the environmental management practices adopted by your hotel allowed the hotel to reduce operating costs?

- (5)

- Which practices, in your opinion, have contributed the most to cost reduction?

- (6)

- Do you consider that the implementation of sustainability practices has contributed to increase/decrease customer satisfaction towards the hotel? If yes, why?

- (7)

- Do you consider that quality and efficiency have changed with the adoption of environmental practices? In what way?

- (8)

- Do you consider that the implementation of sustainability practices has contributed to an increased level of employee satisfaction?

Appendix C

References

- Dhingra, R.; Kress, R.; Upreti, G. Does lean mean green? J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 85, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.S.; Okumus, F.; Chan, W. The applications of environmental technologies in hotels. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2017, 26, 23–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segarra-Oña, M.D.V.; Peiró-Signes, A.; Albors-Garrigós, J.; Miret-Pastor, P. Impact of innovative practices in environmentally focused firms: Moderating factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2011, 5, 425–434. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.J.; Joglekar, N.; Verma, R. Pushing the frontier of sustainable service operations management: Evidence from US hospitality industry. J. Serv. Manag. 2012, 23, 377–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, M.; Bienstock, C.C. Corporate sustainability: An integrative definition and framework to evaluate corporate practice and guide academic research. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 76, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modica, P.D.; Altinay, L.; Farmaki, A.; Gursoy, D.; Zenga, M. Consumer perceptions towards sustainable supply chain practices in the hospitality industry. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 358–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, C.; Sarıbaş, Ö. Luxury Tourism in Turkey. Int. J. Contemp. Econ. Adm. Sci. 2014, 4, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Amatulli, C.; De Angelis, M.; Stoppani, A. The appeal of sustainability in luxury hospitality: An investigation on the role of perceived integrity. Tour. Manag. 2021, 83, 104–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, N.; Chen, A. Examining consumers’ luxury hotel stay repurchase intentions-incorporating a luxury hotel brand attachment variable into a luxury consumption value model. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 1348–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, N.; Chen, A. Luxury hotels going green–the antecedents and consequences of consumer hesitation. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1374–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscardo, G.; Benckendorff, P. Sustainable luxury: Oxymoron or comfortable bedfellows. In Proceedings of the 2010 international Tourism Conference on Global Sustainable Tourism, Mbombela, Nelspruit, South Africa, 15–19 November 2010; pp. 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, Y.; Tang, L.; Luo, Y. Two decades of research on luxury hotels: A review and research Agenda. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2016, 17, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.; Hillier, D.; Comfort, D. Sustainability in the global hotel industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 26, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Almeida, M.D.M.; Bagur-Femenias, L.; Llach, J.; Perramon, J. Sustainability in small tourist businesses: The link between initiatives and performance. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 21, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travel, W.T.T.C. Tourism: Economic Impact 2018: World; World Travel and Tourism Council: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Robin, C.F.; Pedroche, M.S.C.; Astorga, P.S. Revisiting green practices in the hotel industry: A comparison between mature and emerging destinations. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 1415–1428. [Google Scholar]

- Robin, C.F.; Valencia, J.C.; Muñoz, G.J.; Astorga, P.S.; Martínez, D.Y. Attitude and behavior on hotel choice in function of the perception of sustainable practices. Tour. Manag. Stud. 2016, 12, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragon-Correa, J.A.; Martin-Tapia, I.; de la Torre-Ruiz, J. Sustainability issues and hospitality and tourism firms’ strategies: Analytical review and future directions. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 27, 498–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segarra-Oña, M.D.V.; Peiró-Signes, Á.; Verma, R.; Miret-Pastor, L. Does environmental certification help the economic performance of hotels? Evidence from the Spanish hotel industry. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2012, 53, 242–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, N.; Baris, E. Environmental protection programs and conservation practices of hotels in Ankara, Turkey. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 604–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohdanowicz, P. European hoteliers’ environmental attitudes: Greening the business. Cornell Hotel Restaur. Adm. Q. 2012, 46, 188–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cingoski, V.; Petrevska, B. Making hotels more energy efficient: The managerial perception. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraživanja 2018, 31, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graci, S. Examining the factors that impede sustainability in China’s tourism accommodation industry: A case study of Sanya, Hainan, China. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2012, 19, 38–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miththapala, S.; Jayawardena, C.; Mudadeniya, D. Responding to trends: Environmentally-friendly sustainable operations (ESO) of Sri Lankan hotels. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2013, 5, 442–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Antón, J.M.; del Mar Alonso-Almeida, M.; Celemín, M.S.; Rubio, L. Use of different sustainability management systems in the hospitality industry. The case of Spanish hotels. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 22, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bučar, K. Green Orientation in Tourism of Western Balkan Countries. In Green Economy in the Western Balkans: Towards a Sustainable Future; Emerald Publishing Limited: London, UK, 2017; pp. 175–209. [Google Scholar]

- Prud’homme, B.; Raymond, L. Implementation of sustainable development practices in the hospitality industry: A case study of five Canadian hotels. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 609–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.B.; Kumar, M. Corporate Social Responsibility in Indian Tour Operation Industry. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Syst. 2018, 11, 82. [Google Scholar]

- Kasim, A.; Gursoy, D.; Okumus, F.; Wong, A. The importance of water management in hotels: A framework for sustainability through innovation. J. Sustain. Tour. 2014, 22, 1090–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. European Policy on Corporate Social Responsibility. European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2011. Available online: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2011:0681:FIN:EN:PDF (accessed on 8 November 2020).

- Stylos, N.; Vassiliadis, C. Differences in sustainable management between four-and five-star hotels regarding the perceptions of three-pillar sustainability. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2015, 24, 791–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohdanowicz, P.; Zientara, P. Hotel companies’ contribution to improving the quality of life of local communities and the well-being of their employees. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2009, 9, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherapanukorn, V.; Focken, K. Corporate social responsibility (CSR) and sustainability in Asian luxury hotels: Policies, practices and standards. Asian Soc. Sci. 2014, 10, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattera, M.; Moreno-Melgarejo, A. Strategic Implications of Corporate Social Responsibility in Hotel Industry: A Comparative Research Between NH Hotels and Meliá Hotels International. High. Learn. Res. Commun. 2012, 2, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapiņa, I.; Maurāne, G.; Stariņeca, O. Human resource management models: Aspects of knowledge management and corporate social responsibility. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 110, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mežinska, I.; Lapiņa, I.; Mazais, J. Integrated management systems towards sustainable and socially responsible organisation. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2015, 26, 469–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, K.F.; Thai, V.V.; Wong, Y.D. The effect of continuous improvement capacity on the relationship between of corporate social performance and business performance in maritime transport in Singapore. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2016, 95, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, T.; Fenclova, E.; Dinan, C. Tourism and corporate social responsibility: A critical review and research agenda. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2013, 6, 122–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boley, B.B.; Uysal, M. Competitive synergy through practicing triple bottom line sustainability: Evidence from three hospitality case studies. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2013, 13, 226–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, I. Different shades of green: Environmental management in hotels in Accra. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 16, 450–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kularatne, T.; Wilson, C.; Månsson, J.; Hoang, V.; Lee, B. Do environmentally sustainable practices make hotels more efficient? A study of major hotels in Sri Lanka. Tour. Manag. 2019, 71, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longoni, A.; Cagliano, R. Environmental and social sustainability priorities: Their integration in operations strategies. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2015, 35, 216–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, Á.; Silva, G.M.; Patuleia, M.; González-Rodríguez, M.R. Developing sustainable business models: Local knowledge acquisition and tourism lifestyle entrepreneurship. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Almeida, M.; Llach, J.; Marimon, F. A closer look at the ‘Global Reporting Initiative’ sustainability reporting as a tool to implement environmental and social policies: A worldwide sector analysis. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2014, 21, 318–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohdanowicz, P.; Martinac, I. Determinants and benchmarking of resource consumption in hotels-Case study of Hilton International and Scandic in Europe. Energy Build. 2007, 39, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Styles, D.; Schönberger, H.; Galvez Martos, J.L. Best environmental management practice in the tourism sector. Publ. Off. Eur. Union Luxemb. 2013, 1, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavilanes, J.E.; Ludeña, C.F.; Cassagne, Y.J. Sustainable Practices in Luxury Class and First-Class Hotels of Guayaquil, Ecuador. ROSA DOS VENTOS-Turismo e Hospitalidade 2019, 11, 400–416. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, K.T.; Wang, J.C.; Wang, Y.C. Analysis and benchmarking of greenhouse gas emissions of luxury hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 51, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.H.; Barber, N.; Kim, D.K. Sustainability research in the hotel industry: Past, present, and future. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2015, 28, 576–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, L.C.; Leonidou, C.N.; Fotiadis, T.A.; Aykol, B. Dynamic capabilities driving an eco-based advantage and performance in global hotel chains: The moderating effect of international strategy. Tour. Manag. 2015, 50, 268–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirghafoori, S.H.; Andalib, D.; Keshavarz, P. Developing green performance through supply chain agility in manufacturing industry: A case study approach. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017, 24, 368–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellmeister, A.; Richins, H. Green to Gold: Beneficial Impacts of Sustainability Certification and Practice on Tour Enterprise Performance. Sustainability 2019, 11, 709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Line, N.D.; Hanks, L. The effects of environmental and luxury beliefs on intention to patronize green hotels: The moderating effect of destination image. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24, 904–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohdanowicz, P.; Zientara, P.; Novotna, E. International hotel chains and environmental protection: An analysis of Hilton’s we care! programme (Europe, 2006–2008). J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 797–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, M.R.; Porter, M. Creating shared value. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 62–77. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, P.; Hillier, D.; Comfort, D. Sustainability in the hospitality industry: Some personal reflections on corporate challenges and research agendas. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 36–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carcano, L. Strategic management and sustainability in luxury companies: The IWC case. J. Corp. Citizsh. 2013, 36–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haleem, F.; Farooq, S.; Boer, H.; Gimenez, C. The moderating role of stakeholder pressure in the relationship between CSR practices and financial performance in a globalizing world. In Proceedings of the 22nd International EurOMA Conference, Neuchâtel, Switzerland, 26 June–1 July 2015; The European Operations Management Association: Neuchâtel, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bagur-Femenias, L.; Llach, J.; del Mar Alonso-Almeida, M. Is the adoption of environmental practices a strategical decision for small service companies? An empirical approach. Manag. Decis. 2013, 51, 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meixell, M.J.; Luoma, P. Stakeholder pressure in sustainable supply chain management: A systematic review. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2015, 45, 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoddard, J.E.; Pollard, C.E.; Evans, M.R. The triple bottom line: A framework for sustainable tourism development. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2012, 13, 233–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, E.; Rey-Maquieira, J.; Lozano, J. Economic incentives for tourism firms to undertake voluntary environmental management. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muff, K.; Dyllick, T. What does sustainability for business really mean? And when is a business truly sustainable? In Sustainable Business: A One Planet Approach; Jeanrenaud, S., Gosling, J., Jeanrenaud, J.P., Eds.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2017; Chapter 13; pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Kleindorfer, P.R.; Singhal, K.; Van Wassenhove, L.N. Sustainable operations management. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2005, 14, 482–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gast, J.; Gundolf, K.; Cesinger, B. Doing business in a green way: A systematic review of the ecological sustainability entrepreneurship literature and future research directions. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 147, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golini, R.; Longoni, A.; Cagliano, R. Developing sustainability in global manufacturing networks: The role of site competence on sustainability performance. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2014, 147, 448–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.S.; Hawkins, R. Attitude towards EMSs in an international hotel: An exploratory case study. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 29, 641–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, D.; Jang, J.; Lee, J. Environmental management strategy and organizational citizenship behaviors in the hotel industry: The mediating role of organizational trust and commitment. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 1577–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, L.; Zhang, J.J.; Lawrence, B. The Moderating Role of Hotel Type on Advertising Expenditure Returns in Franchised Chains. J. Advert. 2020, 49, 575–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kularatne, T.; Wilson, C.; Hoang, V.; Lee, B. Technical efficiency and environmental management of hotels: The case of Sri Lanka. In Proceedings of the Western Economic Association International, 12th International Conference, Singapore, 7–10 January 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bello, F.G.; Banda, W.J.; Kamanga, G. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) practices in the hospitality industry in Malawi. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2017, 6, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Hays, D.; Ozretic-Došen, Đ. Greening hotels-building green values into hotel services. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 20, 85–102. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira-Moliner, J.; Font, X.; Tarí, J.J.; Molina-Azorin, J.F.; Lopez-Gamero, M.D.; Pertusa-Ortega, E.M. The Holy Grail: Environmental management, competitive advantage and business performance in the Spanish hotel industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 27, 714–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, I.; Alcaraz, J.M.; Susaeta, L.; Suárez, E.; Pin, J. Managing sustainability for competitive advantage: Evidence from the hospitality industry. IESE Business School Working Paper No. WP-1115-E. 2015. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2598500 (accessed on 8 November 2020).

- Meirinhos, M.; Osório, A. The case study as research strategy in education. EduSer Revista de Educação 2010, 2, 49–65. [Google Scholar]

- Michael, G.; Winfried, R.; Barbara, W. Research Notes and Commentaries: What Passes as a Rigorous Case Study? Strateg. Manag. J. 2008, 29, 1465–1474. [Google Scholar]

- Freitas, W.; Jabbour, C. Using Case Study(S) as a Qualitative Research Strategy: Good Practices and Suggestions. Study Debate Mag. 2011, 18. Available online: http://www.meep.univates.br/revistas/index.php/estudoedebate/article/view/560 (accessed on 9 November 2020).

- Radwan, H.R.; Jones, E.; Minoli, D. Solid waste management in small hotels: A comparison of green and non-green small hotels in Wales. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 533–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kind, A.M.; Borchgrevink, C.P.; Brymer, R.A.; Kacmar, K.M. Customer service behaviour and attitudes amongst hotel managers. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2005, 24, 373–397. [Google Scholar]

- Presbury, R.; Fitzgerald, A.; Chapman, R. Impediments to improvements in service quality in luxury hotels. Manag. Serv. Qual. Int. J. 2005, 15, 357–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrington, T.; Curran, R.; Gori, K.; O’Gorman, K.D.; Queenan, C.J. Corporate social responsibility: Reviewed, rated, and revised. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Luo, Q.; Ritchie, B.W. Afraid to travel after COVID-19? Self-protection, coping and resilience against pandemic ‘travel fear’. Tour. Manag. 2021, 83, 104261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenker, S.; Kock, F. The coronavirus pandemic—A critical discussion of a tourism research agenda. Tour. Manag. 2020, 81, 104164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pereira, V.; Silva, G.M.; Dias, Á. Sustainability Practices in Hospitality: Case Study of a Luxury Hotel in Arrábida Natural Park. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3164. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063164

Pereira V, Silva GM, Dias Á. Sustainability Practices in Hospitality: Case Study of a Luxury Hotel in Arrábida Natural Park. Sustainability. 2021; 13(6):3164. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063164

Chicago/Turabian StylePereira, Vitor, Graça Miranda Silva, and Álvaro Dias. 2021. "Sustainability Practices in Hospitality: Case Study of a Luxury Hotel in Arrábida Natural Park" Sustainability 13, no. 6: 3164. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063164

APA StylePereira, V., Silva, G. M., & Dias, Á. (2021). Sustainability Practices in Hospitality: Case Study of a Luxury Hotel in Arrábida Natural Park. Sustainability, 13(6), 3164. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063164