Impacts of Employee Empowerment and Organizational Commitment on Workforce Sustainability

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Extant Literature

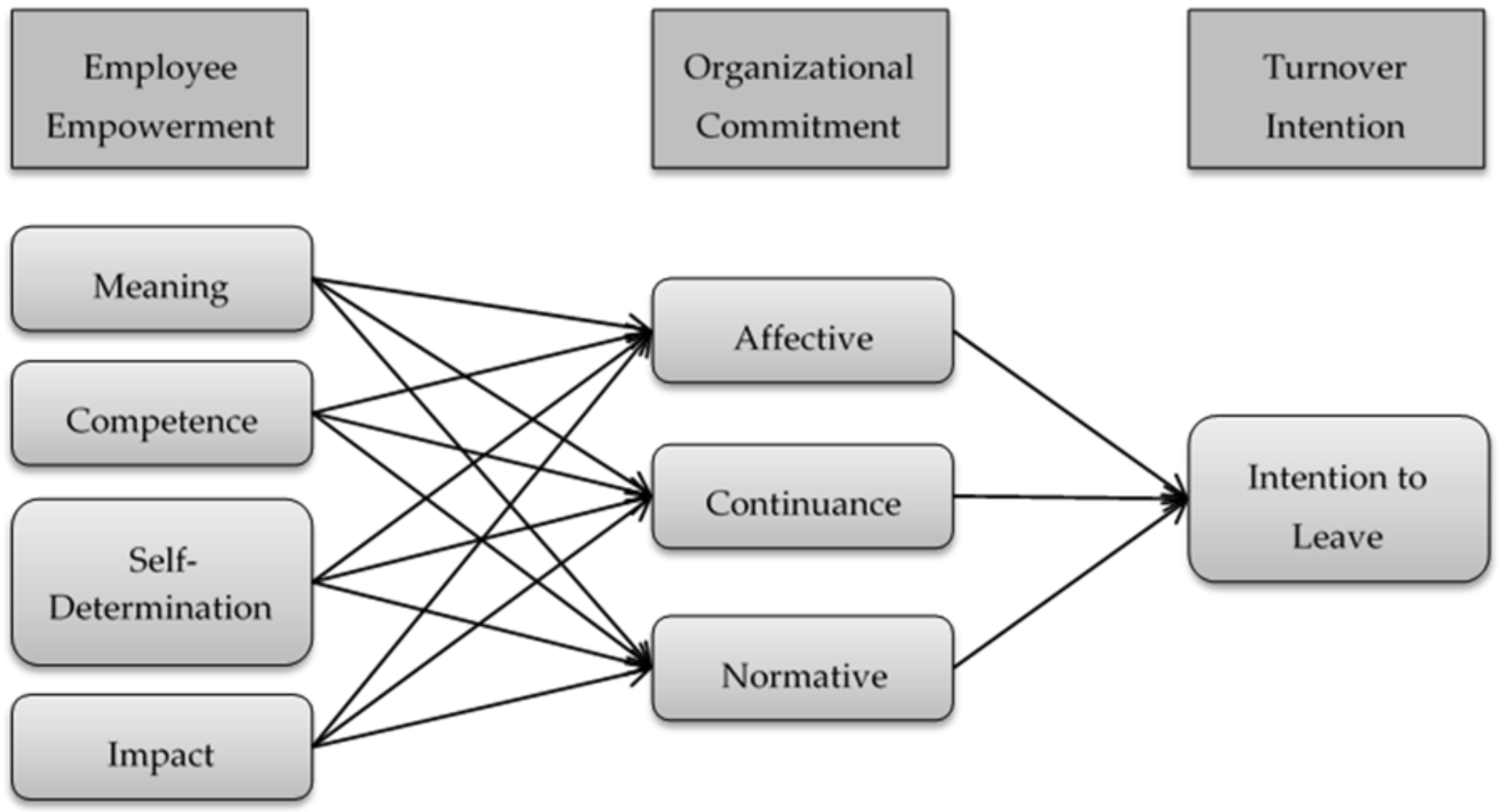

2.2. Hypotheses and Proposed Model

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample

3.2. Measures

3.3. Method of Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Demographics

4.2. Scale Reliability and Validity

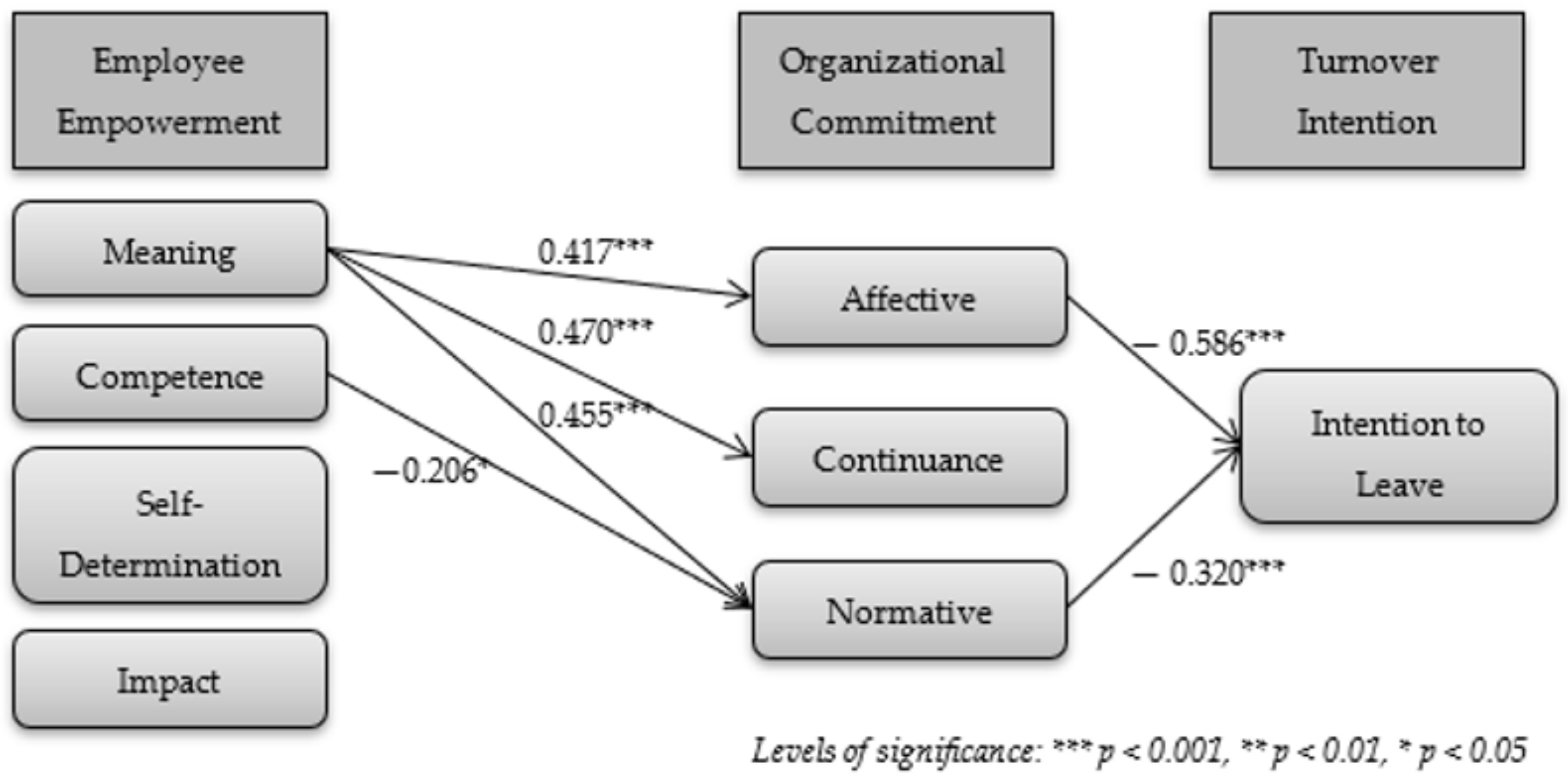

4.3. Structural Equation Modelling

5. Discussion

5.1. Findings and Implications

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bufquin, D.; DiPietro, R.B.; Partlow, C.; Smith, S.J. Differences in social evaluations and their effects on employee job attitudes and turnover intentions in a restaurant setting. J. Hum. Resour. Hosp. Tour. 2018, 17, 375–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, C. Restaurant Outlook Survey. Third Quarter. Available online: https://members.restaurantscanada.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/ROS-Q3-Final.pdf. (accessed on 16 September 2018).

- Destination Analysts. Tourism Market Research Blog; Destination Analysts: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, R.E.; Heckman, R.J. Talent management: A critical review. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2006, 16, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collings, D.G.; Mellahi, K. Strategic talent management: A review and research agenda. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2009, 19, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.C.; Murray, W.C. Evolving conceptions of talent management: A roadmap for hospitality and tourism. In Handbook of Human Resource Management in the Tourism and Hospitality Industries; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2018; pp. 153–183. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, E.; Lee, H. Employee Compensation Strategy as Sustainable Competitive Advantage for HR Education Practitioners. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daghfous, A.; Belkhodja, O. Managing Talent Loss in the Procurement Function: Insights from the Hospitality Industry. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.S.; Song, M.K.; Yoon, H.H. The Effects of Workplace Loneliness on Work Engagement and Organizational Commitment: Moderating Roles of Leader-Member Exchange and Coworker Exchange. Sustainability 2021, 13, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourism HR Canada. Tourism Labour Force Survey. Available online: https://tourismhr.ca/labour-market-information/tourism-labour-force-surve (accessed on 4 March 2021).

- Hotel Association of Canada. Available online: http://www.hotelassociation.ca (accessed on 4 March 2021).

- Labour Shortages; Hotel Association of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2019.

- CTRI. Bottom Line: Labour Challenges Threaten Tourism’s Growth; Canadian Tourism Research Institute: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Labour Market Information: Tourism Facts; Tourism HR Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2020.

- MacLean, K.; Cowan, A.; Coburn, K. Compensation Planning Outlook 2019: With Winter Update; Conference Board of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- R.A. Malatest & Associates. 2012 Canadian Tourism Sector Compensation Study; Canadian Tourism Human Resource Council: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Michaels, E.; Handfield-Jones, H.; Axelrod, B. The War for Talent; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- DiPietro, R.B.; Kline, S.F.; Nierop, T. Motivation and Satisfaction of Lodging Employees: An Exploratory Study of Aruba. J. Hum. Resour. Hosp. Tour. 2014, 13, 253–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, W.C. Preferred Job Rewards and Motivations of Canadian Hotel Employees. J. Hum. Resour. Hosp. Tour 2021, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, W. Leadership as Empowering Others. In Executive Power: How Executives Influence People and Organizations; Srivastva, S., Ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Conger, J.A.; Kanungo, R.N. The Empowerment Process: Integrating Theory And Practice. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1988, 13, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, B.; Han, H. The Effects of Empowerment on Employee Psychological Outcomes in Upscale Hotels. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2014, 23, 218–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.Y.Y. The Essence of Empowerment: A Conceptual Model and a Case Illustration. J. Appl. Manag. Stud. 1998, 7, 223–238. [Google Scholar]

- Daily, B.F.; Bishop, J.W. TQM Workforce Factors and Employee Involvement: The Pivotal Role of Teamwork. J. Manag. Issues 2003, 15, 393–412. [Google Scholar]

- Spreitzer, G.M. When Organizations Dare: The Dynamics of Individual Empowerment in the Workplace. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Michigan, Michigan, MI, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, K.; Velthouse, B. Cognitive Elements of Empowerment. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1990, 15, 666–681. [Google Scholar]

- Gist, M.E. Self-Efficacy: Implications for Organizational Behavior and Human Resource Management. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1987, 12, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Connell, J.P.; Ryan, R.M. Self-Determination in a Work Organization. J. Appl. Psychol. 1989, 74, 580–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B. The experience of powerlessness in organizations. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1989, 43, 207–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, R.C.; Fottler, M.D. Empowerment: A matter of degree. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 1995, 9, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geralis, M.; Terziovski, M. A quantitative analysis of the relationship between empowerment practices and service quality outcomes. Total. Qual. Manag. Bus. Excel. 2003, 14, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsun, D.L.; Enz, C.A. Predicting Psychological Empowerment among Service Workers: The Effect of Support-Based Relationships. Hum. Relat. 1999, 52, 205–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitner, M.J.; Booms, B.H.; Tetreault, M.S. The Service Encounter: Diagnosing Favorable and Unfavorable Incidents. J. Mark. 1990, 54, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolich, M.B. Alienating and liberating emotions at work. J. Contemp. Ethnogr. 1993, 22, 361–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Tayitiyaman, P.; Kim, W. The Effect of Management Commitment to Service on Employee Service Behaviors: The Mediating Role of Job Satisfaction. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2009, 33, 369–390. [Google Scholar]

- Mowday, R.T.; Steers, R.M.; Porter, L.W. The measurement of organizational commitment. J. Vocat. Behav. 1979, 14, 224–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, J.E.; Zajac, D.M. A Review and Meta-Analysis of the Antecedents, Correlates, and Consequences of Organizational Commitment. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 108, 171–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N.J. A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 1991, 1, 61–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, N.J.; Meyer, J.P. The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. J. Occup. Psychol. 1990, 63, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somers, M. Organizational Commitment, Turnover and Absenteeism: An Examination of Direct and Indirect Effects. J. Organ. Behav. 1995, 16, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N.J.; Smith, C.A. Commitment to Organizations and Occupations: Extension and Test of a Three-Component Conceptualization. J. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 78, 538–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.; Schuler, R.S. A meta-analysis and conceptual critique of research on role ambiguity and role conflict in work settings. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1985, 36, 16–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, P.; Santos, V.; Reis, I.; Martinho, F.; Martinho, D.; Sampaio, M.C.; Sousa, M.J.; Au-Yong-Oliveira, M. Strategic Talent Management: The Impact of Employer Branding on the Affective Commitment of Employees. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousef, D.A. Islamic work ethic—A moderator between organizational commitment and job satisfaction in a cross-cultural context. Pers. Rev. 2001, 30, 152–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heskett, J.L.; Sasser, W.E.; Schlesinger, L.A. The Service Profit Chain: How Leading Companies Link Profit and Growth to Loyalty, Satisfaction, and Value; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberg, R.J.; Lance, C.E. Examining the Causal Order of Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment. J. Manag. 1992, 18, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, M.; Cukier, W.; Holmes, M.R.; Hannan, C.-A. Career Satisfaction: A Look behind the Races. Relat. Ind. 2010, 65, 584–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, L.K.; Page, T.J.; Young, C.E. Assessing Hierarchical Differences in Job-Related Attitudes and Turnover among Retail Managers. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1996, 24, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, M.R. Organizational Commitment, Job Satisfaction, and Effort in the Service Environment. J. Psychol. 2001, 135, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishop, J.W.; Scott, K.D. An examination of organizational and team commitment in a self-directed team environment. J. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 85, 439–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbery, R.; Garavan, T.N.; O’Brien, F.; McDonnell, J. Predicting hotel managers’ turnover cognitions. J. Manag. Psychol. 2003, 18, 649–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusluvan, S.; Kusluvan, Z. Perceptions and attitudes of undergraduate tourism students towards working in the tourism industry in Turkey. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 251–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinkin, T.R.; Tracey, J.B. The Cost of Turnover. Cornell Hotel. Restaur. Adm. Q. 2000, 41, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearlman, D.; Schaffer, J. Labour Issues within the Hospitality and Tourism Industry: A Study of Louisiana’s Attempted Solutions. J. Hum. Resour. Hosp. Tour. 2013, 12, 217–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.; Johanson, M.M.; Guchait, P. Employees intent to leave: A comparison of determinants of intent to leave versus intent to stay. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trice, H.M.; Mowday, R.T.; Porter, L.W.; Steers, R.M. Employee-Organization Linkages: The Psychology of Commitment, Absenteeism, and Turnover. Contemp. Sociol. A J. Rev. 1984, 13, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nancarrow, S.; Bradbury, J.; Pit, S.W.; Ariss, S. Intention to Stay and Intention to Leave: Are They Two Sides of the Same Coin? A Cross-sectional Structural Equation Modelling Study among Health and Social Care Workers. J. Occup. Health 2014, 56, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, H.; Sun, N.; Yan, Q. New generation, psychological empowerment. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 2553–2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, K.; Su, S.; Munir, R. The relationship between the enabling use of controls, employee empowerment, and performance. Pers. Rev. 2018, 47, 257–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K.; Torres, E.; Ingram, W.; Hutchinson, J. A review of high performance work practices (HPWPs) literature and recommendations for future research in the hospitality industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 365–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humborstad, S.I.W.; Perry, C. Employee Empowerment, Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment: An in-Depth Empirical Investigation. Chin. Manag. Stud. 2011, 5, 325–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhaimi, S.A.; Abdullah, S.A.; Mohamad, M.; Yahya, K.S.; Razali, N.I. The Effects of Employee Empowerment, Teamwork and Training towards Organizational Commitment among Hotel Employees in Melaka. Glob. Bus. Manag. Int. J. 2018, 10, 734–742. [Google Scholar]

- Karatepe, O.M. High-Performance Work Practices, Perceived Organizational Support, and Their Effects on Job Outcomes: Test of a Mediational Model. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2015, 16, 203–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.M. Psychological empowerment and organizational commitment among employees in the lodging industry. J. Hum. Resour. Hosp. Tour. 2020, 19, 277–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzoli, G.; Hancer, M.; Park, Y. Employee Empowerment and Customer Orientation: Effects on Workers’ Attitudes in Restaurant Organizations. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2012, 13, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, C.-F. The Antecedents and Consequences of Psychological Empowerment: The Case of Taiwan’s Hotel Companies. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2008, 32, 40–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G.M. Psychological Empowerment in the Workplace: Dimensions, Measurement, and Validation. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 1442–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A.P. (Ed.) Discovering Statistics Using SPSS, 2nd ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, H.S.; Yoon, H.H. The effects of organizational service orientation on person–organization fit and turnover intent. Serv. Ind. J. 2013, 33, 7–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Palomo, D.; León-Gómez, A.; García-Lopera, F. Disentangling Organizational Commitment in Hospitality Industry: The Roles of Empowerment, Enrichment, Satisfaction and Gender. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 90, 102637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourism HR Canada. National Summary: Profile of Canada’s Tourism Employees. Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis, 5th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper, D.; Coughlan, J.; Mullen, M. Structural Equation Modelling: Guidelines for Determining Model Fit. Electron. J. Bus. Res. Methods 2008, 6, 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler, P.M. EQS Structural Equations Program Manual; Multivariate Software, Inc.: Encino, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Tepeci, M.; Bartlett, A. The hospitality industry culture profile: A measure of individual values, organizational culture, and person–organization fit as predictors of job satisfaction and behavioral intentions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2002, 21, 151–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: Towards a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables (n = 346) | # | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | Gender | Female | 212 | 61.3% |

| Male | 134 | 38.7% | ||

| Age | Less than 25 | 82 | 23.7% | |

| 26 to 30 | 77 | 22.3% | ||

| 31 to 40 | 83 | 24.0% | ||

| 41 to 50 | 56 | 16.2% | ||

| 51 and older | 48 | 13.9% | ||

| Education | High School | 96 | 27.7% | |

| Technical/Vocational School | 26 | 7.5% | ||

| College Diploma | 110 | 31.8% | ||

| University: Undergraduate Degree | 90 | 26.0% | ||

| University: Graduate Degree | 24 | 6.9% | ||

| Job Characteristics | Income (per year) | Under USD 20,000 | 51 | 14.7% |

| USD 20,001 to 30,000 | 83 | 24.0% | ||

| USD 30,001 to 40,000 | 72 | 20.8% | ||

| USD 40,001 to 60,000 | 77 | 22.3% | ||

| USD 60,001 to 80,000 | 30 | 8.7% | ||

| Over USD 80,000 | 33 | 9.5% | ||

| Position | Line Employee | 166 | 48.0% | |

| Supervisory | 68 | 19.7% | ||

| Management | 80 | 23.1% | ||

| Executive | 32 | 9.2% | ||

| Length of Service | Less than 1 year | 71 | 20.5% | |

| 1 year to less than 2 years | 56 | 16.2% | ||

| 2 year to less than 5 years | 90 | 26.0% | ||

| 5 year to less than 10 years | 65 | 18.8% | ||

| Over 10 years | 64 | 18.5% | ||

| Construct | Individual Variable | Factor Loading | AVE | CR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employee Empowerment | Meaning | The work I do is very important to me | 0.875 | 0.808 | 0.927 |

| My job activities are personally meaningful to me | 0.897 | ||||

| The work I do is meaningful to me | 0.924 | ||||

| Competence | I am confident about my ability to do my job | 0.841 | 0.668 | 0.858 | |

| I am self-assured about my capabilities to perform my work activities | 0.848 | ||||

| I have mastered the skills necessary for my job | 0.760 | ||||

| Self- Determination | I have significant autonomy in determining how I do my job | 0.789 | 0.680 | 0.864 | |

| I can decide on my own how to go about doing my work | 0.810 | ||||

| I have considerable opportunity for independence and freedom in how I do my job | 0.873 | ||||

| Impact | The impact I have on what happens in my department is large | 0.746 | 0.766 | 0.906 | |

| I have a great deal of control over what happens in my department | 0.952 | ||||

| I have significant influence over what happens in my department | 0.913 | ||||

| Organizational Commitment | Affective | I feel a strong sense of belonging to my organization | 0.797 | 0.610 | 0.824 |

| I feel emotionally attached to this organization | 0.787 | ||||

| I feel like a part of the family at my organization | 0.758 | ||||

| Continuance | I feel that I have too few options to consider leaving this organization | 0.806 | Na | Na | |

| Normative | Even if it were to my advantage, I do not feel it would be right to leave my organization now | 0.670 | 0.553 | 0.860 | |

| I would feel guilty if I left my organization now | 0.743 | ||||

| This organization deserves my loyalty | 0.788 | ||||

| I would not leave my organization right now because I have a sense of obligation to the people in it | 0.760 | ||||

| I owe a great deal to my organization | 0.751 | ||||

| Intention to Leave | Currently, I am seriously considering leaving my current job to work at another company | 0.877 | 0.640 | 0.899 | |

| I sometimes feel compelled to quit my job in my current workplace | 0.766 | ||||

| I will probably look for a new job in the next year | 0.805 | ||||

| Within the next 6 months, I would rate the likelihood of leaving my present job as high | 0.793 | ||||

| I will quit this company if the given condition gets even a little worse than now | 0.753 | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Murray, W.C.; Holmes, M.R. Impacts of Employee Empowerment and Organizational Commitment on Workforce Sustainability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3163. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063163

Murray WC, Holmes MR. Impacts of Employee Empowerment and Organizational Commitment on Workforce Sustainability. Sustainability. 2021; 13(6):3163. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063163

Chicago/Turabian StyleMurray, William C., and Mark R. Holmes. 2021. "Impacts of Employee Empowerment and Organizational Commitment on Workforce Sustainability" Sustainability 13, no. 6: 3163. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063163

APA StyleMurray, W. C., & Holmes, M. R. (2021). Impacts of Employee Empowerment and Organizational Commitment on Workforce Sustainability. Sustainability, 13(6), 3163. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063163