The Debate If Agents Matter vs. the System Matters in Sustainability Transitions—A Review of the Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Systemic typology, which consists of the levels of the multilevel perspective;

- Institutional typology, which consists of state, market and civil society;

- Governance typology, including actors at different levels of governance;

- Intermediaries.

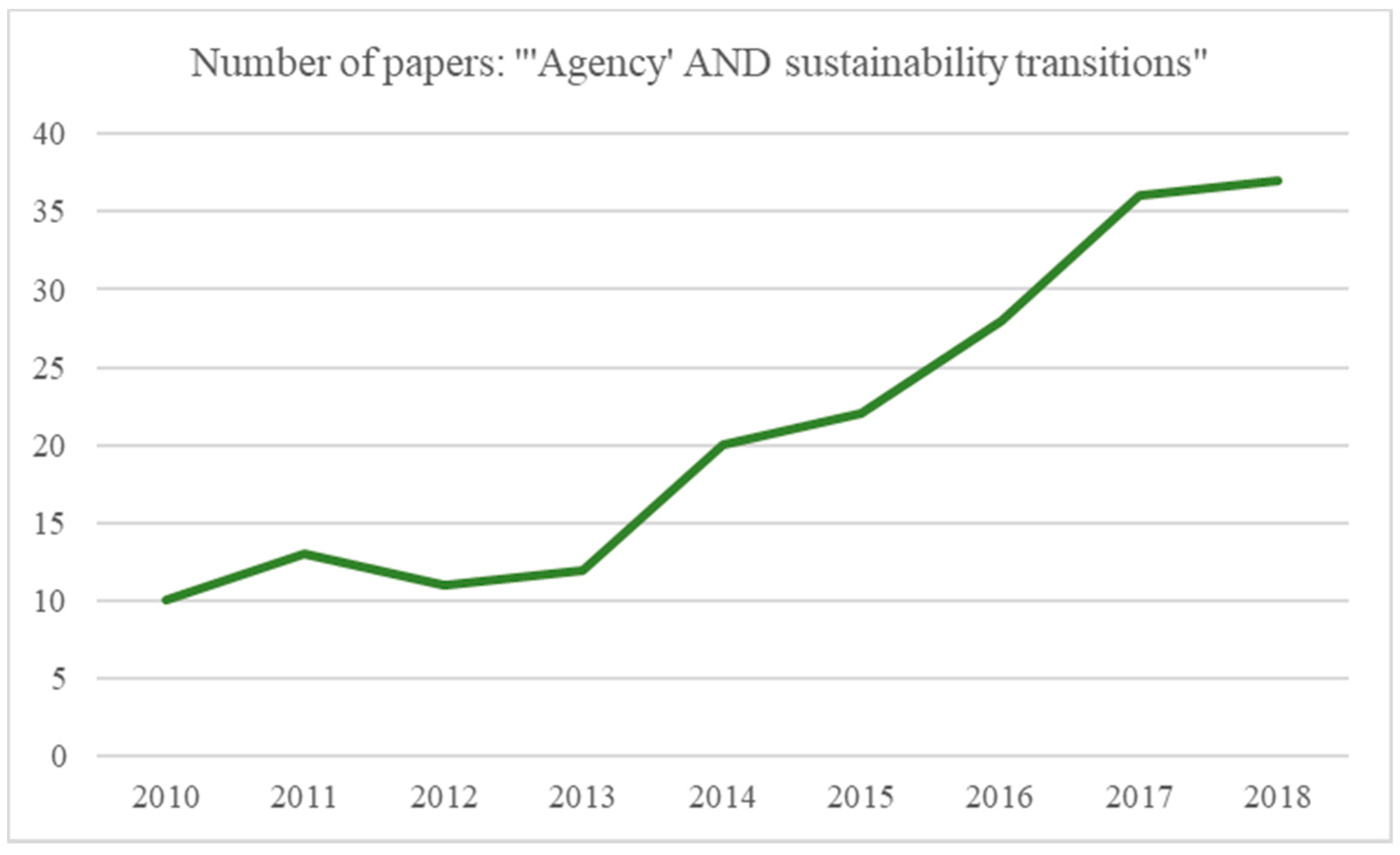

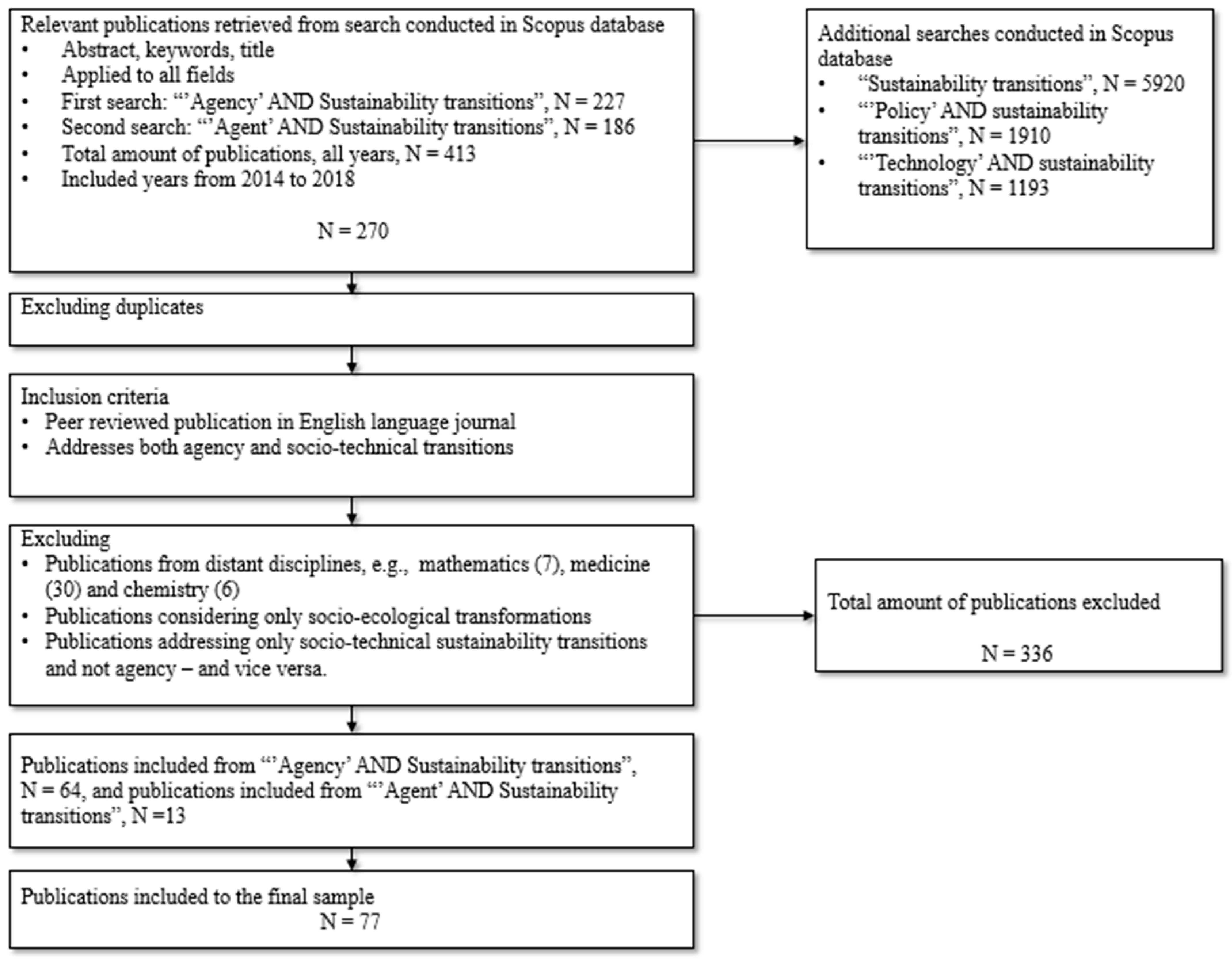

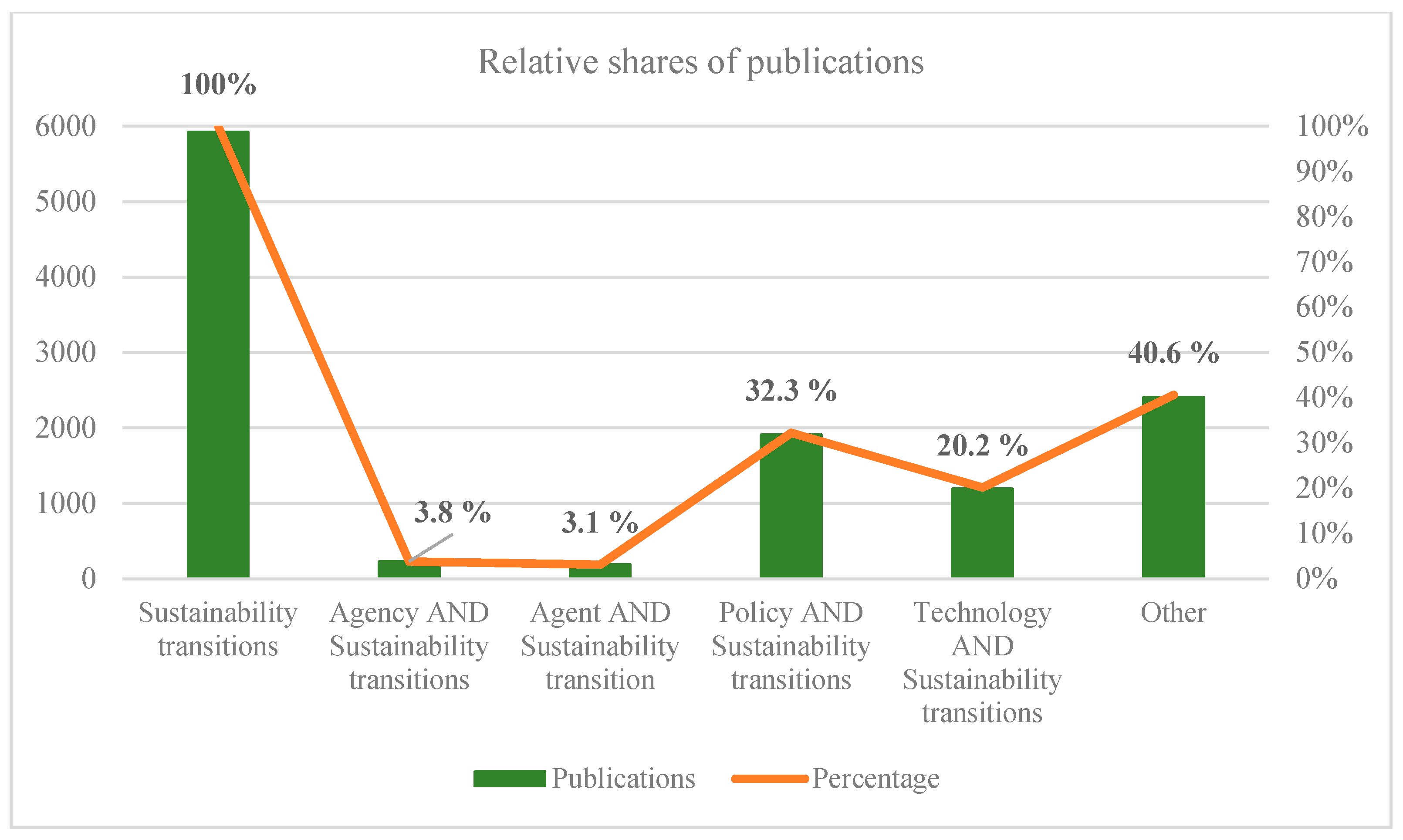

2. Research Methods and Setting

3. A Descriptive Analysis of the Sampled Articles

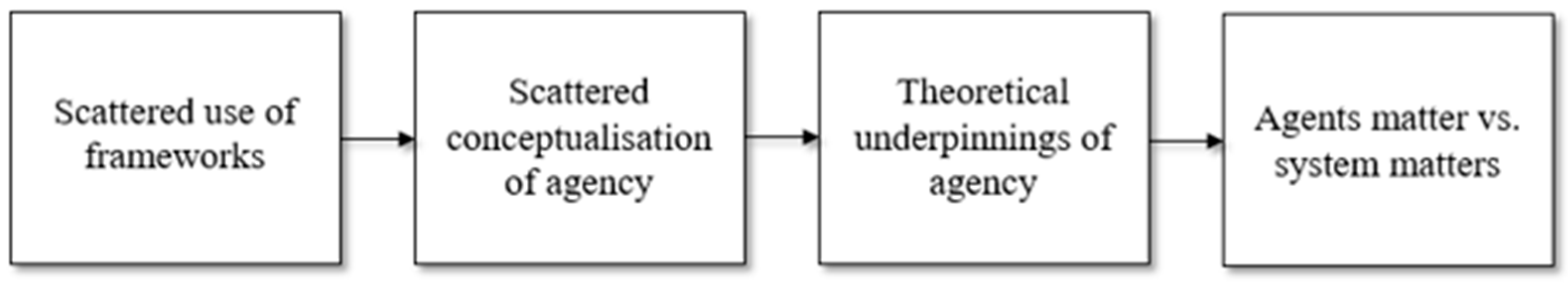

4. Conceptual Critique of the Literature

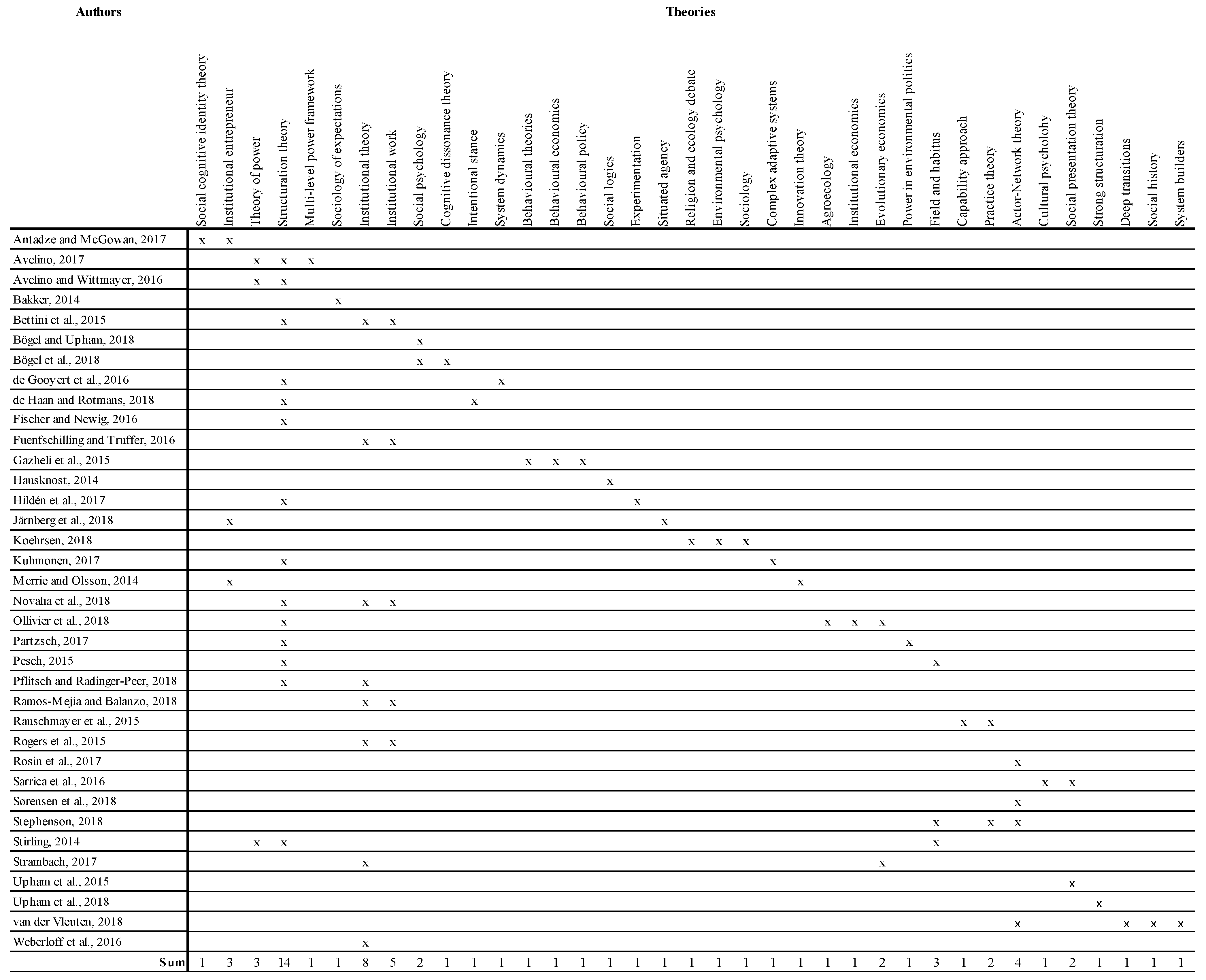

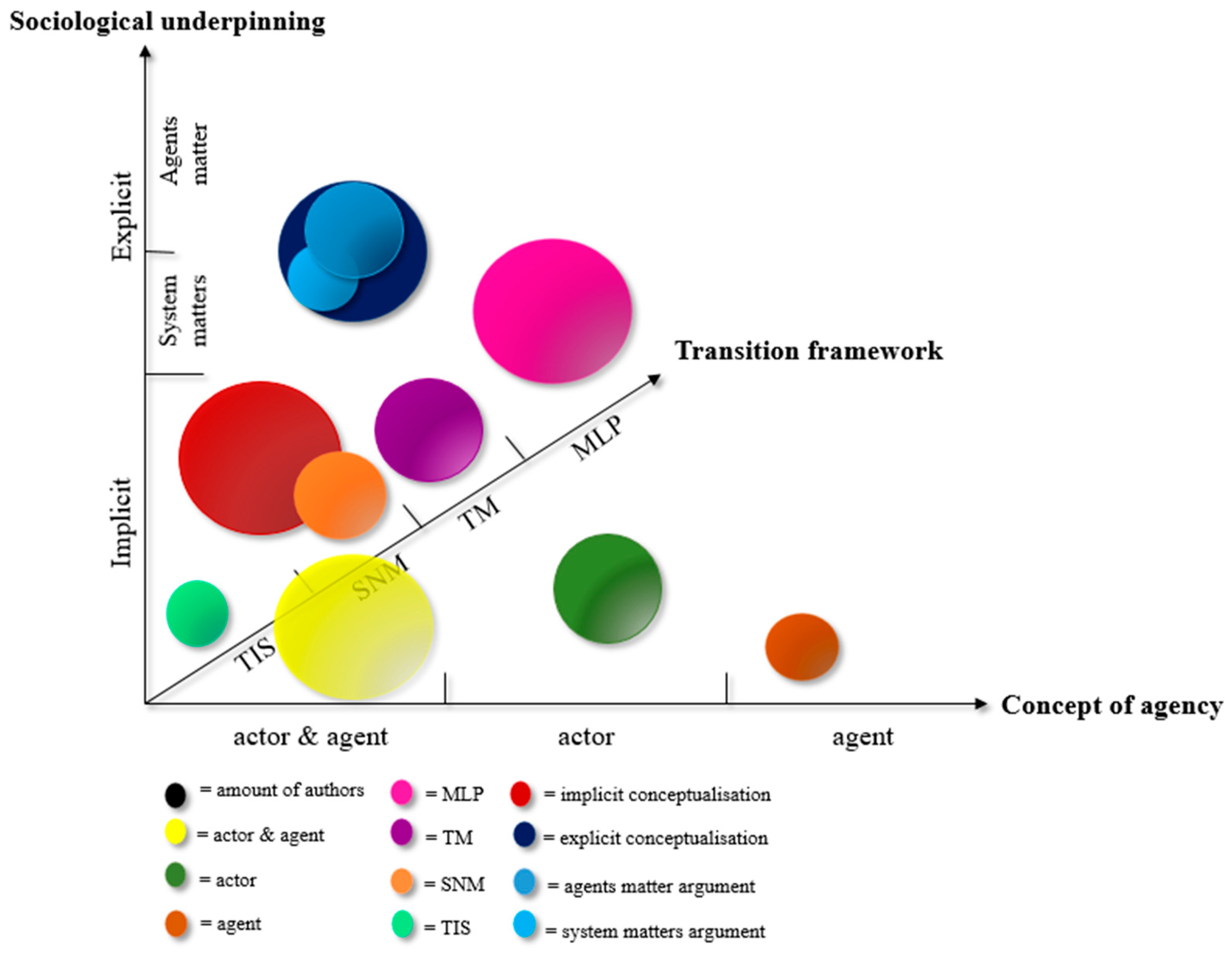

4.1. Scattered Use of Frameworks

4.2. Scattered Conceptualizations of Agency

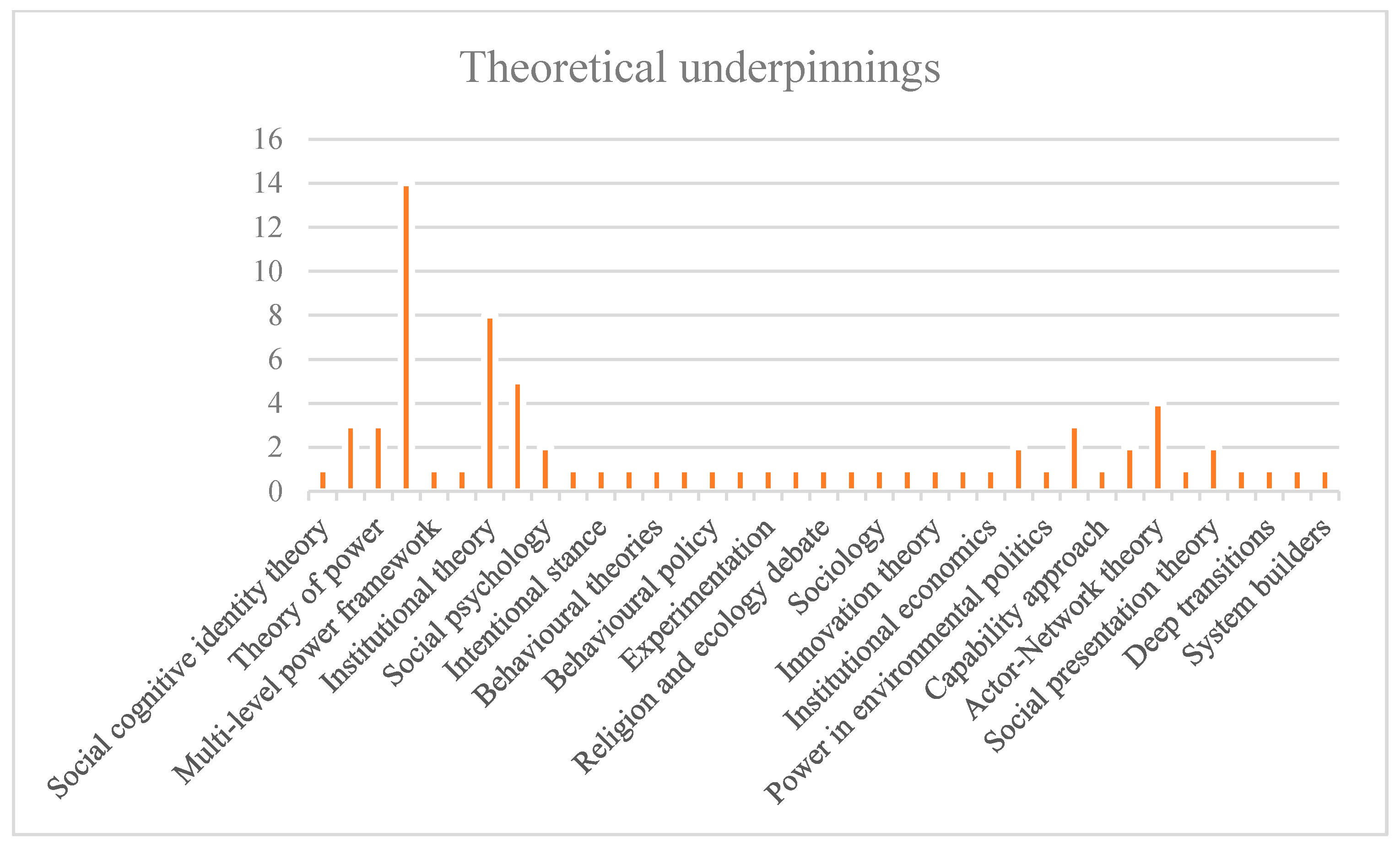

4.3. Theoretical Underpinnings of Agency

4.4. Agents Matter vs. System Matters

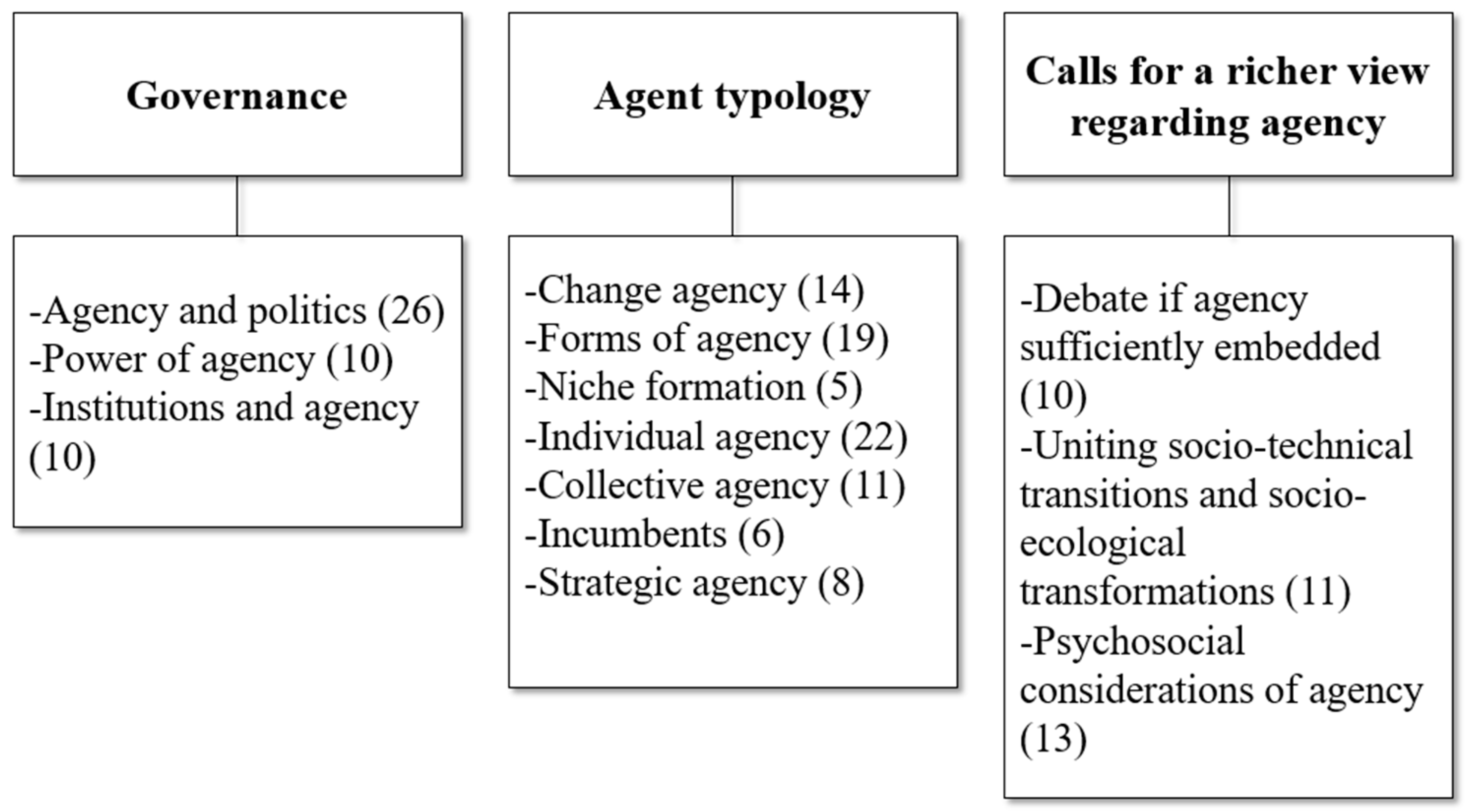

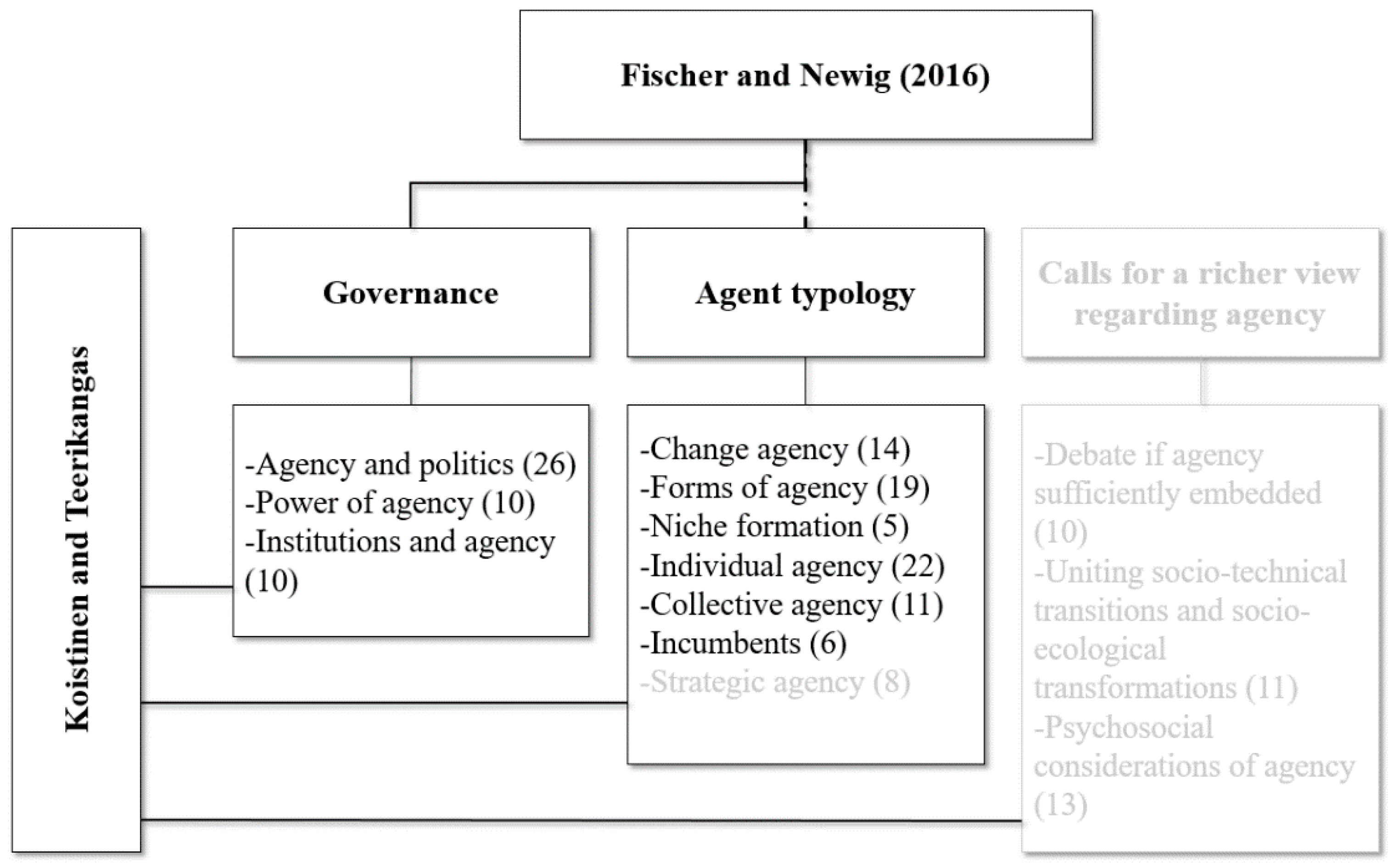

5. Continuous Emphasis on Governance and Agent Typologies

6. Conclusions

Limitations of Our Research and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Year | Authors | Publication |

|---|---|---|

| 2014 | Arapostathis, S., Pearson, P.J.G., Foxon, T.J. | UK natural gas system integration in the making, 1960–2010: Complexity, transitional uncertainties and uncertain transitions |

| 2014 | Bakker, S. | Actor rationales in sustainability transitions—Interests and expectations regarding electric vehicle recharging |

| 2014 | Frantzeskaki, N., Wittmayer, J., Loorbach, D. | The role of partnerships in “realising” urban sustainability in Rotterdam’s City Ports Area, the Netherland |

| 2014 | Hausknost, D. | Decision, choice, solution: “agentic deadlock” in environmental politics |

| 2014 | Merrie, A., Olsson, P. | An innovation and agency perspective on the emergence and spread of Marine Spatial Planning |

| 2014 | Stirling, A. | Transforming power: Social science and the politics of energy choices |

| 2014 | Wittmayer, J.M., Schäpke, N. | Action, research and participation: roles of researchers in sustainability transitions |

| Sum | 7 | |

| 2015 | Bergek, A., Hekkert, M., Jacobsson, S., Markard, J., Sandén, B., Truffer, B. | Technological innovation systems in contexts: Conceptualizing contextual structures and interaction dynamics |

| 2015 | Bettini, Y., Brown, R.R., de Haan, F.J., Farrelly, M. | Understanding institutional capacity for urban water transitions |

| 2015 | Bolton, R., Foxon, T.J., Hall, S. | Energy transitions and uncertainty: Creating low carbon investment opportunities in the UK electricity sector |

| 2015 | Ferguson, R.S., Lovell, S.T. | Grassroots engagement with transition to sustainability |

| 2015 | Gazheli, A., Antal, M., van den Bergh, J. | The behavioral basis of policies fostering long-run transitions: Stakeholders, limited rationality and social context |

| 2015 | Kern, F. | Engaging with the politics, agency and structures in the technological innovation systems approach |

| 2015 | Mercure, J.F. | An age structured demographic theory of technological change |

| 2015 | Pesch, U. | Tracing discursive space: Agency and change in sustainability transitions |

| 2015 | Rauschmayer, F., Bauler, T., Schäpke, N. | Towards a thick understanding of sustainability transitions—Linking transition management, capabilities and social practices |

| 2015 | Rogers, B.C., Brown, R.R., De Haan, F.J., Deletic, A. | Analysis of institutional work on innovation trajectories in water infrastructure systems of Melbourne, Australia |

| 2015 | Sorrell, S. | Reducing energy demand: A review of issues, challenges and approaches |

| 2015 | Upham, P., Lis, A., Riesch, H., Stankiewicz, P. | Addressing social representations in socio-technical transitions with the case of shale gas |

| Sum | 12 | |

| 2016 | Avelino, F., Wittmayer, J.M. | Shifting power relations in sustainability transitions: A multi-actor perspective |

| 2016 | Chelleri, L., Kua, H.W., Sánchez, J.P.R., Md Nahiduzzaman, K., Thondhlana, G. | Are people responsive to a more sustainable, decentralized, and user-driven management of urban metabolism? |

| 2016 | Condorelli, R. | Complex Systems Theory: Some Considerations for Sociology. |

| 2016 | Davidson, D.J., Jones, K.E., Parkins, J.R. | Food safety risks, disruptive events and alternative beef production: a case study of agricultural transition in Alberta |

| 2016 | de Gooyert, V., Rouwette, E., van Kranenburg, H., Freeman, E., van Breen, H. | Sustainability transition dynamics: Towards overcoming policy resistance |

| 2016 | de Haan, F.J., Rogers, B.C., Brown, R.R., Deletic, A. | Many roads to Rome: The emergence of pathways from patterns of change through exploratory modelling of sustainability transitions |

| 2016 | Fischer, L-B., Newig, J. | Importance of actors and agency in sustainability transitions: A systematic exploration of the literature |

| 2016 | Fuenfschilling, L., Truffer, B. | The interplay of institutions, actors and technologies in socio-technical systems—An analysis of transformations in the Australian urban water sector |

| 2016 | Gaede, J., Meadowcroft, J. | A question of authenticity: Status quo bias and the international energy agency’s world energy outlook |

| 2016 | Gorissen, L., Vrancken, K., Manshoven, S. | Transition thinking and business model innovation-towards a transformative business model and new role for the reuse centers of Limburg, Belgium |

| 2016 | Hermans, F., Roep, D., Klerkx, L. | Scale dynamics of grassroots innovations through parallel pathways of transformative change |

| 2016 | Mercure, J.F., Pollitt, H., Bassi, A.M., Viñuales, J.E., Edwards, N.R. | Modelling complex systems of heterogeneous agents to better design sustainability transitions policy |

| 2016 | Pitt, H., Jones, M. | Scaling up and out as a pathway for food system transitions |

| 2016 | Sarrica, M., Brondi, S., Cottone, P., Mazzara, B.M. | One, no one, one hundred thousand energy transitions in Europe: The quest for a cultural approach |

| 2016 | Stahlbrand, L. | The Food For Life Catering Mark: Implementing the Sustainability Transition in University Food Procurement |

| 2016 | Werbeloff, L., Brown, R.R., Loorbach, D. | Pathways of system transformation: Strategic agency to support regime change |

| 2016 | Wolfram, M., Frantzeskaki, N. | Cities and systemic change for sustainability: Prevailing epistemologies and an emerging research agenda |

| Sum | 17 | |

| 2017 | Affolderbach, J., Rob Krueger, R. | ‘“Just” ecopreneurs: reconceptualising green transitions and entrepreneurship’ |

| 2017 | Antadze, N., McGowan, K.A. | Moral entrepreneurship: Thinking and acting at the landscape level to foster sustainability transitions |

| 2017 | Avelino, F. | Power in Sustainability Transitions: Analysing power and (dis)empowerment in transformative change towards sustainabilit |

| 2017 | Haley, B. | Designing the public sector to promote sustainability transitions: Institutional principles and a case study of ARPA-E |

| 2017 | Hildén, M., Jordan, A., Huitema, D. | Special issue on experimentation for climate change solutions editorial: The search for climate change and sustainability solutions—The promise and the pitfalls of experimentation |

| 2017 | Johannessen, Å., Wamsler, C. | What does resilience mean for urban water services? |

| 2017 | Klinke, A. | Dynamic multilevel governance for sustainable transformation as postnational configuration |

| 2017 | Kuhmonen, T. | Exposing the attractors of evolving complex adaptive systems by utilising futures images: Milestones of the food sustainability journey |

| 2017 | Lockwood, M., Kuzemko, C., Mitchell, C., Hoggett, R. | Historical institutionalism and the politics of sustainable energy transitions: A research agenda. |

| 2017 | Loorbach, D., Frantzeskaki, N., Avelino, F. | Sustainability Transitions Research: Transforming Science and Practice for Societal Change |

| 2017 | Partzsch, L. | “Power with” and “power to” in environmental politics and the transition to sustainability |

| 2017 | Pesch, U., Vernay, A.L., van Bueren, E., Pandis Iverot, S. | Niche entrepreneurs in urban systems integration: On the role of individuals in niche formation |

| 2017 | Randelli, F., Rocchi, B. | Analysing the role of consumers within technological innovation systems: The case of alternative food networks |

| 2017 | Udovyk, O. | “I cannot be passive as I was before”: learning from grassroots innovations in Ukraine |

| 2017 | van Poeck, K., Læssøe, J., Block, T. | An exploration of sustainability change agents as facilitators of nonformal learning: Mapping a moving and intertwined landscape |

| Sum | 15 | |

| 2018 | Barnes, J., Durrant, R., Kern, F., MacKerron, G. | The institutionalisation of sustainable practices in cities: how initiatives shape local selection environments |

| 2018 | Boodoo, Z., Mersmann, F., Olsen, K.H. | The implications of how climate funds conceptualize transformational change in developing countries |

| 2018 | Brundiers, K., Eakin, H.C. | Leveraging post-disasterwindows of opportunities for change towards sustainability: A framework |

| 2018 | Bögel, P., Oltra, C., Sala, R., Lores, M., Upham, P., Dütschke, E., Schneider, U., Wiemann, P. | The role of attitudes in technology acceptance management: Reflections on the case of hydrogen fuel cells in Europe |

| 2018 | Bögel, P.M., Upham, P., 2018 | The role of psychology in sociotechnical transitions literature: A review and discussion in relation to consumption and technology acceptance |

| 2018 | de Haan, F.J., Rotmans, J. | A proposed theoretical framework for actors in transformative change |

| 2018 | Durrant, R., Barnes, J., Kern, F., Mackerron, G. | The acceleration of transitions to urban sustainability: a case study of Brighton and Hove |

| 2018 | Goyal, N., Howlett, M. | Technology and instrument constituencies as agents of innovation: Sustainability transitions and the governance of urban transport |

| 2018 | Järnberg, L., Enfors Kautsky, E., Dagerskog, L., Olsson, P. | Green niche actors navigating an opaque opportunity context: Prospects for a sustainable transformation of Ethiopian agriculture |

| 2018 | Kivimaa, P., Martiskainen, M. | Dynamics of policy change and intermediation: The arduous transition towards low-energy homes in the United Kingdom |

| 2018 | Kivimaa, P., Boon, W., Hyysalo, S., Klerkx, L. | Towards a typology of intermediaries in sustainability transitions: A systematic review and a research agenda |

| 2018 | Koehrsen, J. | Religious agency in sustainability transitions: Between experimentation, upscaling, and regime support |

| 2018 | Kuokkanen, A., Nurmi, A., Mikkilä, M., Kuisma, M., Kahiluoto, H., Linnanen, L. | Agency in regime destabilization through the selection environment: The Finnish food system’s sustainability transition |

| 2018 | Matschoss, K., Heiskanen, E. | Innovation intermediary challenging the energy incumbent: enactment of local socio-technical transition pathways by destabilisation of regime rules |

| 2018 | Mossberg, J., Söderholm, P., Hellsmark, H., Nordqvist, S. | Crossing the biorefinery valley of death? Actor roles and networks in overcoming barriers to a sustainability transition |

| 2018 | Novalia, W., Brown, R.R., Rogers, B.C., Bos, J.J. | A diagnostic framework of strategic agency: Operationalising complex interrelationships of agency and institutions in the urban infrastructure sector |

| 2018 | Ollivier, G., Magda, D., Mazé, A., Plumecocq, G., Lamine, C. | Agroecological transitions: What can sustainability transition frameworks teach us? An ontological and empirical analysis |

| 2018 | Pflitsch, G., Radinger-Peer, V. | Developing boundary-spanning capacity for regional sustainability transitions-A comparative case study of the universities of Augsburg (Germany) and Linz (Austria) |

| 2018 | Pigford, A.A.E., Hickey, G.M., Klerkx, L. | Beyond agricultural innovation systems? Exploring an agricultural innovation ecosystems approach for niche design and development in sustainability transitions |

| 2018 | Ramos-Mejía, M., Balanzo, A. | What it takes to lead sustainability transitions from the bottom-up: Strategic interactions of grassroots ecopreneurs |

| 2018 | Stephenson, J. | Sustainability cultures and energy research: An actor-centred interpretation of cultural theory |

| 2018 | Sørensen, K.H., Lagesen, V.A., Hojem, T.S.M. | Articulations of sustainability transition agency. Mundane transition work among consulting engineers |

| 2018 | Temper, L., Walter, M., Rodriguez, I., Kothari, A., Turhan, E. | A perspective on radical transformations to sustainability: resistances, movements and alternatives |

| 2018 | Upham, P., Dütschke, E., Schneider, U., Oltra, C., Sala, R., Lores, M., Klapper, R., Bögel, P. | Agency and structure in a sociotechnical transition: Hydrogen fuel cells, conjunctural knowledge and structuration in Europe |

| 2018 | van der Vleuten, E. | Radical change and deep transitions: Lessons from Europe’s infrastructure transition 1815–2015 |

| 2018 | Wanner, M., Hilger, A., Westerkowski, J., Rose, M., Stelzer, F., Schäpke, N. | Towards a Cyclical Concept of Real-World Laboratories: A Transdisciplinary Research Practice for Sustainability Transitions |

| Sum | 26 | |

| Total | 77 |

Appendix B

References

- Rockström, J.; Steffen, W.; Noone, K.; Persson, Å.; Chapin, F.S.; Lambin, E.F.; Lenton, T.M.; Scheffer, M.; Folke, C.; Schellnhuber, H.J.; et al. A safe operating space for humanity. Nature 2009, 461, 472–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagerberg, J. Mobilizing innovation for sustainability transitions: A comment on transformative innovation policy. Res. Policy 2018, 47, 1568–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levänen, J.; Eloneva, S. Fighting sustainability challenges on two fronts: Material efficiency and the emerging carbon capture and storage technologies. Environ. Sci. Policy 2017, 76, 131–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markard, J.; Raven, R.; Truffer, B. Sustainability transitions: An emerging field of research and its prospects. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 955–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loorbach, D.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Avelino, F. Sustainability Transit. Research: Transforming Science and Practice for Societal Change. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2017, 42, 599–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Haan, F.J.; Rotmans, J. A proposed theoretical framework for actors in transformative change. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2018, 128, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antadze, N.; McGowan, K.A. Moral entrepreneurship: Thinking and acting at the landscape level to foster sustainability transitions. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2017, 25, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivimaa, P.; Boon, W.; Hyysalo, S.; Klerkx, L. Towards a typology of intermediaries in sustainability transitions: A systematic review and a research agenda. Res. Policy 2018, 48, 1062–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avelino, F.; Wittmayer, J.M. Shifting power relations in sustainability transitions: A multi-actor perspective. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2016, 18, 628–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, L.-B.; Newig, J. Importance of actors and agency in sustainability transitions: A systematic exploration of the literature. Sustainability 2016, 8, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Vleuten, E. Radical change and deep transitions: Lessons from Europe’s infrastructure transition 1815-2015. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2018, 32, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesch, U. Tracing discursive space: Agency and change in sustainability transitions. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2015, 90, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddens, A. The Constitution of Society; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Archer, M. Realist Social Theory: The Morphogenetic Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.; Strauss, A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Aldine: Chicago, IL, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Koistinen, K. Actors in Sustainability Transitions; Acta Universitatis Lappeenrantaensis: Lappeenranta, Finland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Matschoss, K.; Heiskanen, E. Innovation intermediary challenging the energy incumbent: Enactment of local socio-technical transition pathways by destabilisation of regime rules. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2018, 30, 1455–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Järnberg, L.; Enfors Kautsky, E.; Dagerskog, L.; Olsson, P. Green niche actors navigating an opaque opportunity context: Prospects for a sustainable transformation of Ethiopian agriculture. Land Use Policy 2018, 71, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, N.; Howlett, M. Technology and instrument constituencies as agents of innovation: Sustainability transitions and the governance of urban transport. Energies 2018, 11, 1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercure, J.F. An age structured demographic theory of technological change. J. Evol. Econ. 2015, 25, 787–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahlbrand, L. The Food For Life Catering Mark: Implementing the Sustainability Transition in University Food Procurement. Agriculture 2016, 6, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Affolderbach, J.; Rob Krueger, R. “Just” ecopreneurs: Reconceptualising green transitions and entrepreneurship. Loc. Environ. 2017, 22, 410–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, J.; Durrant, R.; Kern, F.; MacKerron, G. The institutionalisation of sustainable practices in cities: How initiatives shape local selection environments. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2018, 29, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, R.S.; Lovell, S.T. Grassroots engagement with transition to sustainability. Ecol. Soc. 2015, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossberg, J.; Söderholm, P.; Hellsmark, H.; Nordqvist, S. Crossing the biorefinery valley of death? Actor roles and networks in overcoming barriers to a sustainability transition. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2018, 27, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollivier, G.; Magda, D.; Mazé, A.; Plumecocq, G.; Lamine, C. Agroecological transitions: What can sustainability transition frameworks teach us? An ontological and empirical analysis. Ecol. Soc. 2018, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauschmayer, F.; Bauler, T.; Schäpke, N. Towards a thick understanding of sustainability transitions-Linking transition management, capabilities and social practices. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 109, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfram, M.; Frantzeskaki, N. Cities and systemic change for sustainability: Prevailing epistemologies and an emerging research agenda. Sustainability 2016, 8, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, H.; Jones, M. Scaling up and out as a pathway for food system transitions. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Gooyert, V.; Rouwette, E.; van Kranenburg, H.; Freeman, E.; van Breen, H. Sustainability transition dynamics: Towards overcoming policy resistance. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2016, 111, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanner, M.; Hilger, A.; Westerkowski, J.; Rose, M.; Stelzer, F.; Schäpke, N. Towards a Cyclical Concept of Real-World Laboratories: A Transdisciplinary Research Practice for Sustainability Transitions. Disp 2018, 54, 94–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundiers, K.; Eakin, H.C. Leveraging post-disasterwindows of opportunities for change towards sustainability: A framework. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haley, B. Designing the public sector to promote sustainability transitions: Institutional principles and a case study of ARPA-E. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2017, 25, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazheli, A.; Antal, M.; van den Bergh, J. The behavioral basis of policies fostering long-run transitions: Stakeholders, limited rationality and social context. Futures 2015, 69, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuenfschilling, L.; Truffer, B. The interplay of institutions, actors and technologies in socio-technical systems-An analysis of transformations in the Australian urban water sector. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2016, 103, 298–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durrant, R.; Barnes, J.; Kern, F.; Mackerron, G. The acceleration of transitions to urban sustainability: A case study of Brighton and Hove. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2018, 26, 1537–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, F. Engaging with the politics, agency and structures in the technological innovation systems approach. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2015, 16, 67–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelleri, L.; Kua, H.W.; Sánchez, J.P.R.; Md Nahiduzzaman, K.; Thondhlana, G. Are people responsive to a more sustainable, decentralized, and user-driven management of urban metabolism? Sustainability 2016, 8, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udovyk, O. “I cannot be passive as I was before”: Learning from grassroots innovations in Ukraine. Eur. J. Res. Educ. Learn. Adults 2017, 8, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pigford, A.A.E.; Hickey, G.M.; Klerkx, L. Beyond agricultural innovation systems? Exploring an agricultural innovation ecosystems approach for niche design and development in sustainability transitions. Agric. Syst. 2018, 164, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randelli, F.; Rocchi, B. Analysing the role of consumers within technological innovation systems: The case of alternative food networks. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2017, 25, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bögel, P.; Oltra, C.; Sala, R.; Lores, M.; Upham, P.; Dütschke, E.; Schneider, U.; Wiemann, P. The role of attitudes in technology acceptance management: Reflections on the case of hydrogen fuel cells in Europe. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 188, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condorelli, R. Complex Systems Theory: Some Considerations for Sociology. Open J. App. Sci. 2016, 6, 422–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields. Amer. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettini, Y.; Brown, R.R.; de Haan, F.J.; Farrelly, M. Understanding institutional capacity for urban water transitions. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2015, 94, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novalia, W.; Brown, R.R.; Rogers, B.C.; Bos, J.J. A diagnostic framework of strategic agency: Operationalising complex interrelationships of agency and institutions in the urban infrastructure sector. Environ. Sci. Policy 2018, 83, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werbeloff, L.; Brown, R.R.; Loorbach, D. Pathways of system transformation: Strategic agency to support regime change. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 66, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, B.C.; Brown, R.R.; De Haan, F.J.; Deletic, A. Analysis of institutional work on innovation trajectories in water infrastructure systems of Melbourne, Australia. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2015, 15, 42–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrie, A.; Olsson, P. An innovation and agency perspective on the emergence and spread of Marine Spatial Planning. Mar. Policy 2014, 44, 366–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Mejía, M.; Balanzo, A. What it takes to lead sustainability transitions from the bottom-up: Strategic interactions of grassroots ecopreneurs. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avelino, F. Power in Sustainability Transitions: Analysing power and (dis)empowerment in transformative change towards sustainability. Environ. Policy Gov. 2017, 27, 505–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildén, M.; Jordan, A.; Huitema, D. Special issue on experimentation for climate change solutions editorial: The search for climate change and sustainability solutions-The promise and the pitfalls of experimentation. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 169, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, J. Sustainability cultures and energy research: An actor-centred interpretation of cultural theory. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 44, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stones, R. Structuration Theory; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhmonen, T. Exposing the attractors of evolving complex adaptive systems by utilising futures images: Milestones of the food sustainability journey. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2017, 114, 214–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pflitsch, G.; Radinger-Peer, V. Developing boundary-spanning capacity for regional sustainability transitions-A comparative case study of the universities of Augsburg (Germany) and Linz (Austria). Sustainability 2018, 10, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partzsch, L. “Power with” and “power to” in environmental politics and the transition to sustainability. Environ. Polit. 2017, 26, 193–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stirling, A. Transforming power: Social science and the politics of energy choices. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2014, 1, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A. The odd couple: Margaret Archer, Anthony Giddens and British social theory. British Soc. J. 2010, 61, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, S. Actor rationales in sustainability transitions-Interests and expectations regarding electric vehicle recharging. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2014, 13, 60–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausknost, D. Decision, choice, solution: “agentic deadlock” in environmental politics. Environ. Polit. 2014, 23, 357–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upham, P.; Dütschke, E.; Schneider, U.; Oltra, C.; Sala, R.; Lores, M.; Klapper, R.; Bögel, P. Agency and structure in a sociotechnical transition: Hydrogen fuel cells, conjunctural knowledge and structuration in Europe. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 37, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehrsen, J. Religious agency in sustainability transitions: Between experimentation, upscaling, and regime support. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2018, 27, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bögel, P.; Upham, P. The role of psychology in sociotechnical transitions literature: A review and discussion in relation to consumption and technology acceptance. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2018, 28, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F. Ontologies, socio-technical transitions (to sustainability), and the multi-level perspective. Res. Policy 2010, 39, 495–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, O.R. A survey of general systems theory. Gen. Syst. 1964, 9, 61–80. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, R.R.; Winter, S. An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Dosi, G. Technological paradigms and technological trajectories: A suggested interpretation of the determinants and directions of technical change. Res. Policy 1982, 6, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.W.; Rowan, B. Institutionalized organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. Amer. J. Soc. 1977, 83, 340–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.J. Interest and Agency in Institutional Theory. In Institutional Patterns in Organizations: Culture and Environments; Zucker, L.G., Ed.; Ballinger Publishing: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Garud, R.; Jain, S.; Kumaraswamy, A. Institutional entrepreneurship in the sponsorship of common technological standards: The case of Sun Microsystems and Java. Acad. Manag. J. Manag. J. 2002, 45, 196–214. [Google Scholar]

- King, A. Against structure: A critique of morphogenetic social theory. Soc. Rev. 1999, 47, 199–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritzer, G.; Stepnisky, J. Sociological Theory; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Ann. Rev. Psych. 2001, 52, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaede, J.; Meadowcroft, J. A question of authenticity: Status quo bias and the international energy agency’s world energy outlook. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2016, 18, 608–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arapostathis, S.; Pearson, P.J.G.; Foxon, T.J. UK natural gas system integration in the making, 1960-2010: Complexity, transitional uncertainties and uncertain transitions. Environ. Innov. Soc. Trans. 2014, 11, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, M.; Kuzemko, C.; Mitchell, C.; Hoggett, R. Historical institutionalism and the politics of sustainable energy transitions: A research agenda. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2017, 35, 312–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercure, J.F.; Pollitt, H.; Bassi, A.M.; Viñuales, J.E.; Edwards, N.R. Modelling complex systems of heterogeneous agents to better design sustainability transitions policy. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2016, 37, 102–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boodoo, Z.; Mersmann, F.; Olsen, K.H. The implications of how climate funds conceptualize transformational change in developing countries. Clim. Dev. 2018, 10, 673–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinke, A. Dynamic multilevel governance for sustainable transformation as postnational configuration. Innovation 2017, 30, 323–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorissen, L.; Vrancken, K.; Manshoven, S. Transition thinking and business model innovation-towards a transformative business model and new role for the reuse centers of Limburg, Belgium. Sustainability 2016, 8, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesch, U.; Vernay, A.L.; van Bueren, E.; Pandis Iverot, S. Niche entrepreneurs in urban systems integration: On the role of individuals in niche formation. Environ. Plan. A 2017, 49, 1922–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Poeck, K.; Læssøe, J.; Block, T. An exploration of sustainability change agents as facilitators of nonformal learning: Mapping a moving and intertwined landscape. Ecol. Soc. 2017, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittmayer, J.M.; Schäpke, N. Action, research and participation: Roles of researchers in sustainability transitions. Sustain. Sci. 2014, 9, 483–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermans, F.; Roep, D.; Klerkx, L. Scale dynamics of grassroots innovations through parallel pathways of transformative change. Ecol. Econ. 2016, 130, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergek, A.; Hekkert, M.; Jacobsson, S.; Markard, J.; Sandén, B.; Truffer, B. Technological innovation systems in contexts: Conceptualizing contextual structures and interaction dynamics. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2015, 16, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, R.; Foxon, T.J.; Hall, S. Energy transitions and uncertainty: Creating low carbon investment opportunities in the UK electricity sector. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2015, 34, 1387–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Haan, F.J.; Rogers, B.C.; Brown, R.R.; Deletic, A. Many roads to Rome: The emergence of pathways from patterns of change through exploratory modelling of sustainability transitions. Environ. Model. Softw. 2016, 85, 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, K.H.; Lagesen, V.A.; Hojem, T.S.M. Articulations of sustainability transition agency. Mundane transition work among consulting engineers. Environ. Innov. Soc. Trans. 2018, 28, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuokkanen, A.; Nurmi, A.; Mikkilä, M.; Kuisma, M.; Kahiluoto, H.; Linnanen, L. Agency in regime destabilization through the selection environment: The Finnish food system’s sustainability transition. Res. Policy 2018, 47, 1513–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantzeskaki, N.; Wittmayer, J.; Loorbach, D. The role of partnerships in “realising” urban sustainability in Rotterdam’s City Ports Area, the Netherlands. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 406–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivimaa, P.; Martiskainen, M. Dynamics of policy change and intermediation: The arduous transition towards low-energy homes in the United Kingdom. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 44, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upham, P.; Lis, A.; Riesch, H.; Stankiewicz, P. Addressing social representations in socio-technical transitions with the case of shale gas. Environ. Innov. Soc. Trans. 2015, 16, 120–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarrica, M.; Brondi, S.; Cottone, P.; Mazzara, B.M. One, no one, one hundred thousand energy transitions in Europe: The quest for a cultural approach. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, D.J.; Jones, K.E.; Parkins, J.R. Food safety risks, disruptive events and alternative beef production: A case study of agricultural transition in Alberta. Agric. Hum. Values 2016, 33, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannessen, Å.; Wamsler, C. What does resilience mean for urban water services? Ecol. Soc. 2017, 22, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorrell, S. Reducing energy demand: A review of issues, challenges and approaches. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 47, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hölscher, K.; Wittmayer, J.; Loorbach, D. Transition versus transformation: What’s the difference? Environ. Innov. Soc. Trans. 2018, 27, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temper, L.; Walter, M.; Rodriguez, I.; Kothari, A.; Turhan, E. A perspective on radical transformations to sustainability: Resistances, movements and alternatives. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 747–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrell, G.; Morgan, G. Sociological Paradigms and Organisational Analysis; Heinemann: Burlington, VT, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

| Journal | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 | 2015 | 2014 | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions | 6 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 15 |

| Sustainability | 3 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| Technological Forecasting & Social Change | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 6 |

| Energy Research & Social Science | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| Ecology and Society | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| Journal of Cleaner Production | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Environmental Science and Policy | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Sustainability Science | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Environmental Politics | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Ecological Economics | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Research Policy | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Technology Analysis & Strategic Management | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Environment and Planning A | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Futures | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Annual Review of Environment and Resources | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Global Environmental Change | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Agricultural Systems | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Energies | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Environmental Policy and Governance | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Land use Policy | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| European Planning Studies | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Economic Geography | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Economy and Space | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Agriculture | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Agriculture and Human Values | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Journal of Evolutionary Economics | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Environmental Modelling & Software | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Local Environment | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| disP—The Planning Review | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Marine Policy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Climate and Development | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| European Journal for Research on the Education and Learning of Adults | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 25 | 17 | 16 | 12 | 7 | 77 |

| Theme | Authors |

|---|---|

| Agency and politics | Arapostathis et al., 2014; Avelino, 2017; Avelino and Wittmayer, 2016; Barnes et al., 2018; Bettini et al., 2015; Bolton et al., 2015; de Gooyert et al., 2016; Frantzeskaki et al., 2014; Gaede and Meadowcroft, 2016; Gazheli et al., 2015; Goyal and Howlett, 2018; Haley, 2017; Hausknost, 2014; Hildén et al., 2017; Kern, 2015; Kivimaa and Martiskainen, 2018; Klinke, 2017; Loorbach et al., 2017; Mercure et al., 2016; Partzsch, 2017; Pesch et al., 2017; Pitt and Jones, 2016; Rosin et al., 2017; Stirling, 2014; Sørensen et al., 2018; Udovyk, 2017 |

| Total: 26 | |

| Individual agency | Antadze and McGowan, 2017; Bakker, 2014; Bögel and Upham, 2018; de Haan and Rotmans, 2018; Fischer and Newig, 2016; Gazheli et al., 2015; Koehrsen, 2018; Kuhmonen, 2017; Kuokkanen et al., 2018; Lockwood et al., 2017; Mercure, 2015; Mossberg et al., 2018; Partzsch, 2017; Pesch, 2015; Pesch et al., 2017; Pflitsch and Radinger-Peer, 2018; Rauschmayer et al., 2015; Sarrica et al., 2016; Stahlbrand, 2016; Upham et al., 2018; van Poeck et al., 2017; Wittmayer and Schäpke, 2014 |

| Total: 22 | |

| Forms of agency | Avelino and Wittmayer, 2016; Bakker, 2014; Bettini et al., 2015; de Haan and Rotmans, 2018; Fischer and Newig, 2016; Gorissen et al., 2016; Goyal and Howlett, 2018; Kivimaa and Martiskainen, 2018; Koehrsen, 2018; Kuokkanen et al., 2018; Matschoss and Heiskanen, 2018; Merrie and Olsson, 2014; Mossberg et al., 2018; Rosin et al., 2017; Stahlbrand, 2016; Sørensen et al., 2018; van Poeck et al., 2017; Wittmayer and Schäpke, 2014; Wolfram and Frantzeskaki, 2016 |

| Total: 19 | |

| Change agency | Affolderbach and Krueger, 2017; Boodoo et al., 2018; Brundiers and Eakin, 2018; Chelleri et al., 2016; Frantzeskaki et al., 2014; Klinke, 2017; Pflitsch and Radinger-Peer, 2018; Pigford et al., 2018; Ramos-Mejía and Balanzo, 2018; Stahlbrand, 2016; Temper et al., 2018; van Poeck et al., 2017; Wanner et al., 2018; Wittmayer and Schäpke, 2014 |

| Total: 14 | |

| Psychosocial considerations of agency | Antadze and McGowan, 2017; Bakker, 2014; Bögel et al., 2018; Bögel and Upham, 2018; Gazheli et al., 2015; Koehrsen, 2018; Pesch, 2015; Sarrica et al., 2016; Sorrell, 2015; Stephenson, 2018; Upham et al., 2015; Upham et al., 2018; van der Vleuten, 2018 |

| Total: 13 | |

| Uniting sociotechnical transitions and socioecological transformations | Brundiers and Eakin, 2018; Davidson et al., 2016; Ferguson and Lovell, 2015; Hausknost, 2014; Johannessen and Wamsler, 2017; Järnberg et al., 2018; Merrie and Olsson, 2014; Ollivier et al., 2018; Pigford et al., 2018; Strambach, 2017; Temper et al., 2018 |

| Total: 11 | |

| Collective agency | Bergek et al., 2015; de Haan and Rotmans, 2018; Durrant et al., 2018; Fischer and Newig, 2016; Frantzeskaki et al., 2014; Hermans et al., 2016; Kuokkanen et al., 2018; Lockwood et al., 2017; Merrie and Olsson, 2014; Mossberg et al., 2018; Sarrica et al., 2016 |

| Total: 11 | |

| Debate if agency sufficiently embedded | Avelino and Wittmayer, 2016; Bakker, 2014; de Haan and Rotmans, 2018; Fischer and Newig, 2016; Gazheli et al., 2015; Pesch, 2015; Sarrica et al., 2016; Upham et al., 2018, Upham et al., 2015; van der Vleuten, 2018 |

| Total: 10 | |

| Power of agency | Avelino, 2017; Avelino and Wittmayer, 2016; Durrant et al., 2018; Järnberg et al., 2018; Lockwood et al., 2017; Loorbach et al., 2017; Partzsch, 2017; Pigford et al., 2018; Randelli and Rocchi, 2017; Stirling, 2014 |

| Total: 10 | |

| Institutions and agency | Antadze and McGowan, 2017; Arapostathis et al., 2014; Barnes et al., 2018; Bettini et al., 2015; Fuenfschilling and Truffer, 2016; Koehrsen, 2018; Lockwood et al., 2017; Novalia et al., 2018; Rogers et al., 2015; Strambach, 2017 |

| Total: 10 | |

| Strategic agency | Bergek et al., 2015; de Haan et al., 2016; Gorissen et al., 2016; Järnberg et al., 2018; Kuokkanen et al., 2018; Novalia et al., 2018; Sørensen et al., 2018; Werbeloff et al., 2016 |

| Total: 8 | |

| Incumbents | Bakker, 2014; Bergek et al., 2015; Bolton et al., 2015; Fischer and Newig, 2016; Lockwood et al., 2017; Matschoss and Heiskanen, 2018 |

| Total: 6 | |

| Niche formation | Gazheli et al., 2015; Hildén et al., 2017; Kivimaa and Martiskainen, 2018; Pesch, 2015; Pesch et al., 2017 |

| Total: 5 |

| Transition Framework | Authors |

|---|---|

| Multilevel perspective | Antadze and McGowan, 2017; Arapostathis et al. 2014; Avelino, 2017; Avelino and Wittmayer, 2016; Bakker, 2014; Bergek et al., 2015; Bolton et al., 2015; Brundiers and Eakin, 2018; Bögel and Upham, 2018; de Gooyert et al., 2016; de Haan and Rotmans, 2018; de Haan et al., 2016; Fischer and Newig, 2016; Gazheli et al., 2015; Gorissen et al., 2016; Goyal and Howlett, 2018; Haley, 2017; Järnberg et al., 2018; Koehrsen 2018; Kuhmonen, 2017; Kuokkanen et al., 2018; Loorbach et al., 2017; Matschoss and Heiskanen, 2018; Hermans et al., 2016; Mercure, 2015; Mossberg et al., 2018; Ollivier et al., 2018; Pesch, 2015; Pitt and Jones, 2016; Rauschmayer et al., 2015; Sarrica et al., 2016; Sørenssen et al., 2018; Sorrell, 2015; Stahlbrandt, 2016; Temper et al., 2018; Upham et al., 2015; Upham et al., 2018; van der Vleuten 2018; Wanner et al., 2018; Wolfram and Frantzeskaki, 2016 |

| Total: 40 | |

| Transition management | Avelino and Wittmayer, 2016; Boodoo et al., 2018; Bettini et al., 2015; Brundiers and Eakin, 2018; de Gooyert et al., 2016; de Haan and Rotmans, 2018; Fischer and Newig, 2016; Frantzeskaki et al., 2014; Fuenfschilling and Truffer; 2016; Gazheli et al., 2015; Gorissen et al., 2016; Hildén et al., 2017; Loorbach et al., 2017; Mossberg et al., 2018; Pesch, 2015; Ollivier et al., 2018; Rauschmayer et al., 2015; van Poeck et al., 2017; Wanner et al., 2018; Wittmayer and Schäpke, 2014; Wolfram and Frantzeskaki, 2016 |

| Total: 21 | |

| Strategic niche management | de Haan and Rotmans, 2018; Fischer and Newig, 2016; Gazheli et al., 2015; Hildén et al., 2017; Kivimaa and Martiskainen, 2018; Loorbach et al., 2017; Mossberg et al., 2018; Ollivier et al., 2018; Pesch, 2015; Pesch et al., 2017; Pitt and Jones, 2016; Ramos-Mejía and Balanzo, 2018; Rauschmayer et al., 2015; Sorrell, 2015; Udovyk, 2017; Wolfram and Frantzeskaki, 2016 |

| Total: 16 | |

| Technological innovation system | Bergek et al., 2015; de Haan and Rotmans, 2018; Fischer and Newig, 2016; Fuenfschilling and Truffer; 2016; Haley, 2017; Kern, 2015; Koehrsen 2018; Loorbach et al., 2017; Mossberg et al., 2018; Ollivier et al., 2018; Randelli and Rocchi, 2017; Wolfram and Frantzeskaki, 2016 |

| Total: 12 | |

| Mix of frameworks | Avelino and Wittmayer, 2016; Bergek et al., 2015; Brundiers and Eakin, 2018; de Goyyert et al., 2016; de Haan and Rotmans, 2018; Fischer and Newig, 2016; Fuenfschilling and Truffer, 2016; Gazheli et al., 2015; Gorissen et al., 2016; Haley, 2017; Hildén, 2017; Koehrsen, 2018; Loorbach et al., 2017; Mossberg et al., 2018; Ollivier et al., 2018; Pesch, 2015; Pitt and Jones, 2016; Rauschmayer et al., 2015; Sorrell, 2015; Wanner et al., 2018; Wolfram and Frantzeskaki, 2017 |

| Total: 21 | |

| Not defined | Affolderbach and Krueger, 2017; Barnes et al., 2018; Bögel et al., 2018; Chelleri et al., 2016; Davidson et al., 2016; Durrant et al., 2018; Ferguson and Lovell, 2015; Gaede and Meadowcroft, 2016; Hausknost, 2014; Johannessen and Wamsler, 2017; Klinke, 2017; Lockwood et al., 2017; Mercure et al., 2016; Merrie and Olsson, 2014; Novalia et al., 2018; Partzsch, 2017; Pflitsch and Radinger-Peer, 2018; Pigford et al., 2018; Rogers et al., 2015; Rosin et al., 2017; Stephenson, 2018; Stirling, 2014; Strambach, 2017; Weberloff et al., 2016 |

| Total: 24 |

| Authors | Frameworks | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MLP | TM | SNM | TIS | |

| Avelino and Wittmayer, 2016 | x | x | ||

| Bergek et al., 2015 | x | x | ||

| Brundiers and Eakin, 2018 | x | x | ||

| de Gooyert et al., 2016 | x | x | ||

| de Haan and Rotmans, 2018 | x | x | x | x |

| Fischer and Newig, 2016 | x | x | x | x |

| Fuenfschilling and Truffer, 2016 | x | x | ||

| Gazheli et al., 2015 | x | x | ||

| Gorissen et al., 2016 | x | x | ||

| Haley, 2017 | x | x | ||

| Hildén et al., 2017 | x | x | ||

| Koehrsen, 2018 | x | x | x | |

| Loorbach et al., 2017 | x | x | x | x |

| Mossberg et al., 2018 | x | x | x | x |

| Ollivier et al., 2018 | x | x | x | x |

| Pesch, 2015 | x | x | x | |

| Pitt and Jones, 2016 | x | x | ||

| Rauschmayer et al., 2015 | x | x | x | x |

| Sorrell, 2015 | x | x | x | |

| Wanner et al., 2018 | x | x | x | |

| Wolfram and Frantzeskaki, 2017 | x | x | x | x |

| Sum | 19 | 17 | 13 | 11 |

| Used Term | Authors |

|---|---|

| Agent and actor | Affolderbach and Krueger, 2017; Antadze and McGowan, 2017; Avelino, 2017; Avelino and Wittmayer, 2016; Barnes et al., 2018; Brundiers and Eakin, 2018; Bögel and Upham, 2018; Davidson et al., 2016; de Gooyert et al., 2016; de Haan and Rotmans, 2018; Ferguson and Lovell, 2015; Frantzeskaki et al., 2014; Gazheli et al., 2015; Goyal and Howlett, 2018; Haley, 2017; Gorissen et al., 2016; Hausknost, 2014; Johanessen and Wamsler, 2017; Klinke, 2017; Loorbach et al., 2017; Matschoss and Heiskanen, 2018; Mossberg et al., 2018; Partzsch, 2017; Pesch 2015; Pesch et al., 2017; Pflitsch and Radinger-Peer, 2018; Pigford et al., 2018; Pitt and Jones, 2016; Ramos-Mejía and Balanzo, 2018; Randelli and Rocchi, 2017; Rauschmayer et al., 2015; Sarrica et al., 2016; Strambach, 2017; Upham et al., 2015; Upham et al., 2018; Temper et al., 2018; van Poeck et al., 2017; Wanner et al., 2018; Weberloff et al., 2016; Wittmayer and Schäpke, 2014 |

| Total: 40 | |

| Actor | Arapostathis et al., 2014; Bakker, 2014; Bergek et al., 2015; Bettini et al., 2015; Bodoo et al., 2018; Bolton et al., 2015; de Haan et al., 2016; Durrant et al., 2018; Fischer and Newig, 2016; Fuenfschilling and Truffer, 2016; Gaede and Meadowcroft, 2016; Hermans et al., 2016; Järnberg et al., 2018; Kern, 2015; Kivimaa and Martiskainen, 2018; Koehrsen, 2018; Kuokkanen et al., 2018; Lockwood et al., 2017; Ollivier et al., 2018; Rogers et al., 2015; Sorrell, 2015; Stirling, 2014; Sørensen et al., 2018; Stephenson, 2018; van der Vleuten, 2018; Wolfram and Frantzeskaki, 2016 |

| Total: 26 | |

| Agent | Chelleri et al., 2016; Hildén et al., 2017; Kuhmonen, 2017; Mercure, 2015; Mercure et al., 2016; Merrie and Olsson, 2014; Novalia et al., 2018; Rosin et al., 2017; Stahlbrand, 2016; Udovyk, 2017 |

| Total: 10 |

| Agency and Sociology Addressed Explicitly | Agency and Sociology Addressed Implicitly |

|---|---|

| Avelino, 2017; Avelino and Wittmayer, 2016; Bakker, 2014; Bettini et al., 2015; Bögel and Upham, 2018; Bögel et al., 2018; de Gooyert et al., 2016; de Haan and Rotmans, 2018; Fischer and Newig, 2016; Fuenfschilling and Truffer 2016; Gazheli et al., 2015; Hildén et al., 2017; Hausknost, 2014; Järnberg et al., 2018; Koehrsen, 2018; Kuhmonen, 2017; Merrie and Olsson, 2014; Novalia et al., 2018; Ollivier et al., 2018; Partzsch, 2017; Pesch, 2015; Pflitsch and Radinger-Peer, 2018; Ramos-Mejía and Balanzo, 2018; Rauschmayer et al., 2015; Rogers et al., 2015; Rosin et al., 2017; Sarrica et al., 2016; Stirling, 2014; Strambach, 2017; Sørensen et al., 2018; Stephenson, 2018; Upham et al., 2015; Upham et al., 2018; van der Vleuten 2018; Weberloff et al., 2016 | Affolderbach and Krueger, 2017; Arapostathis et al., 2014; Barnes et al., 2018; Bergek et al., 2015; Bolton et al., 2015; Bodoo et al., 2018; Brundiers and Eakin, 2018; Chelleri et al., 2016; Davidson et al., 2016; de Haan et al., 2016; Durrant et al., 2018; Ferguson and Lovell, 2015; Frantzeskaki et al., 2014; Gaede and Meadowcroft, 2016; Goyal and Howlett, 2018; Gorissen et al., 2016; Haley, 2017; Hermans et al., 2016; Johannessen and Wamsler, 2017; Kern, 2015; Kivimaa and Martiskainen, 2018; Klinke, 2017; Kuokkanen et al., 2018; Lockwood et al., 2017; Loorbach et al., 2017; Matschoss et al., 2018; Mercure, 2015; Mercure et al., 2016; Mossberg et al., 2018; Pesch et al., 2017; Pigford et al., 2018; Pitt and Jones, 2016; Randelli and Rocchi, 2017; Rosin et al., 2017; Sorrell 2015; Stahlbrand, 2016; van Poeck et al., 2017; Temper et al., 2018; Udovyk, 2017; Wanner et al., 2018; Wittmayer and Schäpke, 2014; Wolfram and Frantzeskaki, 2016 |

| Total: 36 | Total: 41 |

| Agents Matter | System Matters | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Authors | Theoretical Underpinnings | Authors | Theoretical Underpinnings |

| Antadze and McGowan, 2017 | Social cognitive identity theory Institutional entrepreneur | Bettini et al., 2015 | Structuration theory Institutional theory Institutional work |

| Avelino, 2017 | Theory of power Structuration theory Multilevel power framework | de Gooyert et al., 2016 | System dynamics Structuration theory |

| Avelino and Wittmayer, 2016 | Theory of power Structuration theory | Fischer and Newig, 2016 | Structuration theory |

| Bakker, 2014 | Sociology of expectations | Fuenfschilling and Truffer, 2016 | Institutional theory Institutional work |

| Bögel and Upham, 2018 | Social psychology | Kuhmonen, 2017 | Complex adaptive systems Structuration theory |

| Bögel et al., 2018 | Social psychology Cognitive dissonance theory | Merrie and Olsson, 2014 | Innovation theory Institutional entrepreneur |

| de Haan and Rotmans, 2018 | Structuration theory Intentional stance | Novalia et al., 2018 | Structuration theory Institutional theory Institutional work |

| Gazheli et al., 2015 | Behavioral theories Behavioral economics Behavioral policy | Ollivier et al., 2018 | Agroecology Institutional economics Evolutionary economics Structuration theory |

| Hausknost, 2014 | - Social logics | Pflitsch and Radinger-Peer, 2018 | - Institutional theory - Structuration theory |

| Hildén et al., 2017 | Structuration theory Experimentation | Rogers et al., 2015 | Institutional theory Institutional work |

| Järnberg et al., 2018 | Institutional entrepreneur Situated agency | Strambach, 2017 | Institutional theory Evolutionary economics |

| Koehrsen, 2018 | Religion and ecology debate Environmental psychology Sociology | Weberloff et al., 2016 | Institutional theory |

| Partzsch, 2017 | Structuration theory Power in environmental politics | ||

| Pesch, 2015 | Structuration theory Field and habitus | ||

| Ramos-Mejía and Balanzo, 2018 | Institutional theory Institutional work | ||

| Rauschmayer et al., 2015 | Capability approach Practice theory | ||

| Rosin et al., 2017 | Actor–network theory | ||

| Sarrica et al., 2016 | Cultural psychology Social presentation theory | ||

| Sørensen et al., 2018 | Actor–network theory | ||

| Stephenson, 2018 | Cultural theory Practice theory Field and habitus Structuration theory | ||

| Stirling, 2014 | Theory of power Field and habitus Structuration theory | ||

| Upham et al., 2015 | Social representation theory | ||

| Upham et al., 2018 | Strong structuration | ||

| van der Vleuten, 2018 | Deep transitions Social history Actor–network theory System builders | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Koistinen, K.; Teerikangas, S. The Debate If Agents Matter vs. the System Matters in Sustainability Transitions—A Review of the Literature. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2821. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052821

Koistinen K, Teerikangas S. The Debate If Agents Matter vs. the System Matters in Sustainability Transitions—A Review of the Literature. Sustainability. 2021; 13(5):2821. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052821

Chicago/Turabian StyleKoistinen, Katariina, and Satu Teerikangas. 2021. "The Debate If Agents Matter vs. the System Matters in Sustainability Transitions—A Review of the Literature" Sustainability 13, no. 5: 2821. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052821

APA StyleKoistinen, K., & Teerikangas, S. (2021). The Debate If Agents Matter vs. the System Matters in Sustainability Transitions—A Review of the Literature. Sustainability, 13(5), 2821. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052821