1. Introduction

Climate change is happening, even if global efforts to reduce emissions prove effective [

1]. According to recent observations, the global average annual land ocean surface was, in the period 2009–2018, almost 1 degree warmer than the pre-industrial average; the year 2018 was the world’s fourth warmest year on record. Future projections reveal an increase of global temperature between 0.3 and 1.7 degrees (in the lowest emissions scenario) and between 2.6 and 4.8 (for the highest one) (ibid.). The risk of extreme weather and climate-related events (e.g., floods and droughts) will probably increase. This would have an impact on several economic sectors (agriculture and tourism, firstly), natural ecosystems and biodiversity, human health, and well-being [

2,

3,

4].

Adaptation policies to these changes appear urgent and require some form of global collective action [

5]. Climate change is in fact depicted as a problem to be resolved at the international level, as it is characterized by uncertain settings in which unstructured, international, multi-territorial interdependencies dynamically evolve, and where different bodies perceive and assess them differently [

6].

Traditional approaches to this problem view multilateral agreements negotiated by the national government as the central mechanism of climate change governance [

7]. The Paris Conference is at its core and remains a central forum for global climate governance [

8].

Nevertheless, many climate change policies currently can be observed at the most decentralized levels. As suggested by Gupta [

9], more institutions are significantly participating at different levels of society and contribute to a web of policies at different scales and governance structures. In bi- and multilateral agreements, many states coordinate and mutually foster their climate policies [

10] and they also organise some transnational networks, such as C40 or ICLEI, to commit to specific climate targets. Under the umbrella of these agreements and networks, national states also adopt unilateral national climate policies or provide support for national initiatives [

11,

12]. In recent times, other bodies also operate within the same framework: financial institutions, NGOs, corporations, associations, groups of citizens. Their larger participation in the climate change issues restructures the international approaches to climate governance, which were focused mainly on nation states as the only relevant bodies [

13]. Going beyond these approaches would involve reviewing international multilateralism, as well as the cooperative efforts among countries, towards a new, more appropriate arena for climate governance decisions. It also implies the displacing of traditional top-down, institutionally driven climate governance for more polycentric bottom-up strategies where the role of non-state and sub-national actors appears essential [

14]. Finally, it enables the implementation of policies that are targeted more to the specific territories and therefore enables climate governance to be integrated into the multi-focused process of achieving sustainable development also at local level [

15].

In all these respects, the literature advances the discussion on the most appropriate governance structures and stakeholders’ involvement as well as on the coherence of the adopted decisions and mechanisms with the existing and wider-scales strategies. Some scholars assume a sort of shift away from the centrality of the UNFCCC at the international level or the EU at European or national level to an ongoing fragmentation of climate governance. Zelli and van Asselt [

16] or Keohane and Victor [

17] promote the horizontal differentiation at the international level and do not support the hypothesis of a single regime for climate change. By contrast, other authors claim there is potential “anarchic inefficiency” because of this fragmentation of the competences for the adaptation climate policies [

18] or conflicting expectations regarding the role and influence of several bodies [

7]. Others investigate emerging new bodies in the governance arena (NGOs, associations, private citizens, etc), and their relations [

19] or the growth of transnational climate change governance [

20].

This debate has also flourished in Europe, where the European Union contributes to the emerging climate change governance, promoting the initiatives and strategies at the European level as well as in the European countries.

Recently, the EU has presented the EU climate actions [

21] to fight climate change through local policies and close cooperation with international partners. The first climate actions include the European Climate Law to enshrine the 2050 climate-neutrality objective into EU law and the European Climate Pact to engage citizens and all parts of society in climate action. It also comprises the 2030 Climate Target Plan with a list of activities to further reduce net greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% by 2030. The realisation of all these actions will involve the reinforcement of the competences of the central states, as well as the closest collaboration among government institutions, non-governmental bodies and private citizens. With these documents, the EU definitively opens the scenario to other non-governmental bodies but does not restrict specific inclusion to institutional mid-level organisations.

European countries operate by considering an additional layer of regional and macro-regional cooperation that includes climate change alongside many other policies. A European Union (EU) macro-regional strategy is “a policy framework which allows countries located in the same region to jointly tackle and find solutions to problems or to better use the potential they have in common” [

22]. Currently, there are four macro-regions in Europe (Baltic Sea, Danube region, Adriatic-Ionic region, and Alpine region/ EUSALP) which are addressing some common problems related to navigability, pollution, global trade and competition, etc.).

Notwithstanding the increasing attention, precise recommendations for the governance of climate changes at this level are still lacking. Macro-regions span several states with some common climate or morphological features. To govern their territories, they adopt wider-scale strategies which are not mandatory or do not take sufficient account of the specificities of any included regions. Each region is differently administrated according to national and regional laws. In force of these regulations, each of them adopts specific climate adaptation strategies for addressing just the challenges of the territories they govern, without considering the effects on the ones nearby. Thanks to the ongoing decentralisation of the climate policies towards the lowest levels of government, a growing number of nongovernmental organisations and subnational authorities have initiated programmes to share public understanding of climate change or continued to develop innovative policies at lower governmental levels.

Within the macro-regions and across regions, local conditions and climate changes can be similar; however, their impacts can vary significantly at single territory level, and extend their effects beyond traditional administrative boundaries.

To address these impacts and adapt local societies to them, governance of climate issues is expected to take effective and timely responses and to be tailored to the specific communities and localities [

23]. However, several challenging factors can reduce its effectiveness (e.g., multi-actor interest, information scarcity, lack of coordination, geographical specificities, etc.).

This is particularly true and challenging for the Alpine area, which is today a fragile ecosystem due to the current climate changes [

24]. Traditionally, its mountains play an important role in influencing European and local climate conditions, as their presence influences the direction and consistency of wind, precipitation, and temperature. Over the last decades, this role is under pressure as climate change transforms the area in a place of high-risk environments (e.g., glacial lake outburst, avalanches, etc.) [

25]. These changes in turn influence the richness of natural resources, the diversity of the fauna, and the opportunity to exploit them for economic reasons (touristic and agricultural activities) [

26]. Impacts can be different even between similar administrative units, as their effects shape territories independently from the institutional borders set by law [

27]. These borders divide the Alpine area into eight countries (Italy, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, France, Slovenia, Monaco, and Liechtenstein), 48 regions/autonomous provinces and 5700 municipalities. Each institution has specific competences on climate changes policies and adopt different governance structures and mechanisms to govern the administrated territories. In addition to these national, regional and local governments, the following bodies have some degree of authority and actively promote the interests of this area: one international institution (the Alpine Convention), one transnational strategy (EUSALP Strategy), and the European funds beneficiary area (the Alpine area for Alpine Space Program-Interreg).

Despite the plurality of the involved bodies, limited focus is placed on the administrative level at which the respective relative decisions take place or on the relationship between institutional and non-governmental actors. Scarce attention is also given to the governance mechanisms, including planning and programming systems instruments, and their coherence with the existing and wider-scales strategies adopted to address climatic vulnerabilities [

28].

To fill this gap, this paper briefly describes the strategies recently formulated at the European level vis à vis the climate change adaptation for the entire Alpine regions. It also lists some essential characteristics of the governance structures/mechanisms adopted for addressing the specific challenges (risks, vulnerabilities, etc.) connected to climate change in the Alpine regions and specifically in South Tyrol. Beyond these mechanisms, the paper also investigates which are the main stakeholders who have been involved in developing and implementing climate change adaptation strategies in the Alpine regions and in South Tyrol. It also analyses how these strategies relate to EU, transnational, and/or national climate change adaptation strategies and what interactions exist across Alpine, national, and sub-national policy domains. Finally, it reflects on whether these wider-scale strategies take sufficient account of South Tyrol.

Compared to other Alpine regions and autonomous provinces, South Tyrol has greater legislative autonomy, which allows it to adopt more targeted policies in response to the needs of its territory.

For a few years, South Tyrol has been particularly active within EUSALP, and especially in the action groups where climate issues are addressed. This autonomous province has also drafted some strategic plans for the implementation of measures to adapt to climate change, also in collaboration with associations, universities, and local research centres. In 2020, the Joint Research Centre for the Covenant of Mayors of the European Commission approved the PAESC (Action Plan for Sustainable Energy and Climate) for the Municipality of Bolzano, which had already been well-received by the City Council in May. The Plan is the result of a long study carried out with the internal resources of the Municipality, of the Geology, Civil Protection and Energy Office, and it follows the City Council resolution of 2017, with which the City of Bolzano decided to join the Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy. The PAESC identifies the actions necessary to reduce CO2 emissions by at least 40% by 2030, compared to the year 2010, taken as the reference year, and indicates the actions necessary to enable the city to adapt to climate change. In the case of Bolzano, the estimated reduction in emissions is 40.65%, going from 520,700 tons of CO2 in 2010 to 309,046 tons of CO2 in 2030.

Methodologically, the paper is based on a document analysis concerning climate adaptation strategies adopted in the last five years at the European level by the Alpine Convention, EUSALP action groups, the Alpine area for Alpine Space Program-Interreg, and by national and local institutions to govern climate changes in all Alpine regions/autonomous provinces.

The paper is structured as follows. The second section briefly describes some principles of climate change governance while the following section discusses the adopted method. The fourth section briefly explains the climate adaptation strategies adopted by the Alpine Convention, EUSALP action groups, Alpine Space Program-Interreg at European level and by Alpine regions and autonomous provinces in the last 5 years. The next sections illustrate the test area, the South Tyrol, the past and future-estimated climate changes, and their hypothetical impacts on economic activities. The next paragraph answers the various questions that have been raised, specifying the adapted strategies, the institutions and citizens’ involvement and relationship with other strategies at different territorial levels. The final paragraphs encompass discussion and conclusion.

2. Background

Climate change governance refers to a particular decision-making process associated with climate change at multiple levels of administrations and society. It includes decisions regarding the adaptation of territories and individuals to expected and current climate and its effects [

29] and hence is more locally oriented than mitigation policies which include interventions to reduce pollutions and emissions (ibid.). This kind of governance has rapidly evolved into a complex structure that extends from the global to national and macro-regional up to municipal levels [

23].

Negotiations at the international level have shed light on the difficulties in moving towards a great involvement of the singular states within the multilateralism framework, as well as on the peculiarities of interests of different territories. This has brought the climate governance issues under the umbrella of the international community which decides to set common objectives and a minimum framework of procedures and rules. Together, national states aim to achieve global goals, while they define their commitment individually for their reference territory. Within them, other bodies operate and contribute to formulate and implement more detailed strategies (national and local institutions, agencies and individuals). There is, in fact, an ongoing shift in power and authority relations along three dimensions: (i) devolution of power from central to local governments; (ii) increased sharing of power between the state and civil society; (iii) reduction of state sovereignty through joining of international coordination mechanisms [

30]. The resulting increased number of participants reflects the “glocal” nature of climate changes which go beyond administrative boundaries [

31] and confirm the existing mismatches between jurisdictional and climate change challenges scales.

This situation involves implies the adoption of correct decisions in terms of governance structures and mechanisms, stakeholders’ involvement and linkages with the existing and wider-scale strategies.

Underdal (2010) [

32] suggests a more balanced power distribution, which combines sufficiently decentralised adaptive governance for enabling local initiatives to grow, but also fosters networks for the rolling out of best practices and enhancing collective action across scale. Bulkeley (2005) [

33] outlines that environmental decisions are created, constructed, regulated and contested, between, across and among different echelons through networking and this implies in turn that governance occurs through interactions between formal and informal spheres of authority. Many other approaches are formulated and varied in relation to the choices made in terms of shared components (mechanisms, stakeholders’ involvement and links with wider-scale strategies). Sapiains et al. [

7] list 30 different types of climate and/or environmental governance with a focus on climate change and cluster them into six groups. One of these is related to the multi-level governance which gathers different components (organisations, scales and interactions) into a broader scheme (e.g., [

34,

35]). Its imperative characteristic is decentralisation as “decision-making taking place at a range of territorial levels or scales” (Peel et al., 2012, p. 251) [

36]. The emergent actors, in addition to the governmental ones, play an essential role, and do not necessarily cooperate at the same level.

The second cluster includes the approaches which assume it is essential for the global governance to tackle climate change problems. While most of these approaches devote some importance to the national states which continue to play a central role, part of them reveal a great emphasis on developing comprehensive adaptation strategies in which the role of the scientific community become increasingly important (e.g., [

37,

38,

39]).

The third cluster comprises transnational, polycentric and adaptive governance approaches which emphasize the role of private actors in climate governance and the forms of their participation (public–private agreements or informal law-making), as well as of the national states which remain key players in the transnational governance (e.g., [

40,

41]). However, questions about authority and legitimacy of these actors are often neglected with an enthusiastic narrative on transnational initiatives. Unlike these approaches, those included in cluster 4 insist on the role of local communities and city networks. As such, they theorize a sort of “polycentric order” which includes “orchestration” [

14], new instruments to consider transnational law [

35], non-state and sub-state agency and/or actors [

11], and networked governance [

42]. They focus on local experiences, using, as a case study, “urban or local governance”. Other territorial scales, such as the macro-regional level, for example, are ignored.

The last cluster includes an example of transformative and experimental approaches which adopt “learning by doing” mechanisms at more local scales (e.g., [

43]).

The plurality of these approaches depends on the mismatches between jurisdictional and climate change challenges scales. Differences in spatial, time and sectoral scales make it difficult to adopt general or multi-disciplinary plans or long-term strategies at a higher level. Laws on climate change are less frequent and adopted by central government. There might be the problem of overcoming legal inconsistencies and tensions about the distribution of competences across institutional levels among the network, the integration of policies and the presence of local barriers to implementation. Some literature evidence that local actors are likely more engaged in sharing information and collaborating on adaptation issues while international and national actors discuss and collaborate more on mitigation [

44].

Governance of climate changes is crucial in mountain areas and for their resilience. These areas have special vulnerabilities and are among the most exposed and sensitive to climate change. Topography is articulated and, consequently, climate conditions can change at very short distances. Differences in altitude are also important and impact differently on climate conditions. Another impact factor vis à vis mountains concerns the presence of glaciers and permafrost, which may trigger slope instability with the increasing risks of rock fall, mud and debris flows, etc. Changes in atmospheric wind flow patterns induce large, varying precipitations. These peculiarities expose mountains both to the direct effects of climate change (e.g., floods) and indirect (such as loss of biodiversity). Another critical factor is the extent of mountains that exceed administrative boundaries and spread across different regions and nations.

Notwithstanding these geographical and administrative peculiarities, the climate change adaptation governance is often similar to the rest of the country and specific tools are not applied locally. Unconventional schemes are sometimes adopted to tackle the local climatic problems, as well as to coordinate the multiple institutional and non-institutional actors which assist locally. Collaboration between communities is important and can be systematically assessed through the existence and strength of connections between actors and their embeddedness in the broader socio-economic network. For example, Luthe et al. (2012) [

45] demonstrate the existence of a governance network with high diversification capability in the Swiss Gotthard region, which depends on the high cohesion, the close collaboration and the limited innovative capacity. According to the authors, this network is also conditioned by the existence of only two subgroups, and the considerable flexibility through the centralized structure, while its weaknesses are a low density, uneven distribution of power, and a lack of integration of some supply chain sectors into the overall network.

3. The Alps in a Changing Climate

The Alps present a climatic variability that encompasses colder areas at higher altitudes and warmer ones located especially in the valleys. Precipitation is unevenly distributed, with an increasing trend since 1971, in the eastern part of the Alps, and a decreasing one in the western part. Temperatures have also increased in the last few years. Future scenarios reveal that summers will be drier whereas winters with more precipitation will be more likely. Extreme weather events, such as heavy rainfalls and droughts, as well as more days and nights with extreme temperatures, can also be expected. Temperature will increase significantly in the period 2021–2050 (

Figure 1).

Precipitation varies across the Alps. It is most intense in the northern Alps, Ticino (Switzerland), northern Italy, while it is less in the south-western parts of the Alpine arc (

Figure 2).

4. Method

The method adopted in the present paper consists of a document analysis of the most important climate adaptation strategies recently formulated at the European level for the entire Alpine regions. These strategies are directly downloaded from the websites of their adopting institutions and are listed below (

Table 1).

The analysis also includes the study of regional and provincial strategies adopted in the same field by local governments in the largest Alpine states (Austria, Switzerland, Germany, Italy and France) in the last five years. These documents are here listed (

Table 2):

The analysis of both kinds of documents is addressed to detail some essential characteristics of the governmental structure adopted at the regional level for all Alpine regions and specifically for South Tyrol for addressing climate change adaptation issues. Specifically, it investigates: (i) the governance structures and mechanisms, (ii) stakeholders’ involvement and (iii) linkages with the existing and wider-scale strategies. Regarding point (i) the study considers information related to the institutions involved in climate change adaptation policies and the instruments they adopted to formulate and implement them (laws, plans, etc.). Concerning point (ii), it selects the most relevant information about the participation of stakeholders, in particular associations, citizens, non-profit organisations. Finally, regarding point (iii), the analysis reflects on the references to plans, projects, and actions promoted by Alpine Convention, EUSALP and Alpine Space-Interreg in the documents analysed and how the regulations contained in them have been transposed in the documents adopted at the national or regional level.

5. The Climate Adaptation Strategies and Associated Governance Structure for the Alpine Area at European Level

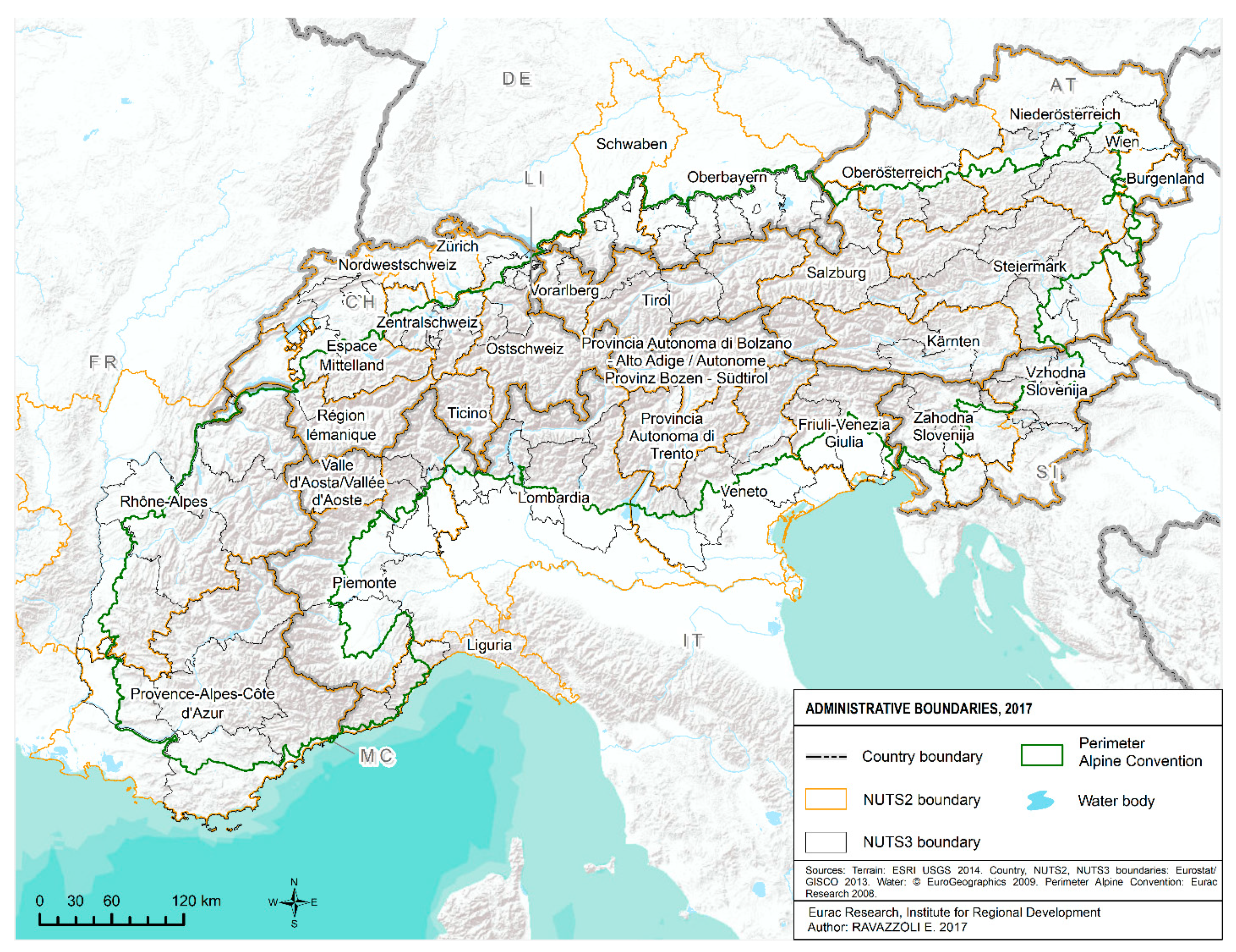

From an administrative point of view, three different institutions operate and have authority in the Alpine area for its promotion: an international institution (the Alpine Convention), a transnational strategy (EUSALP Strategy) and the European funds beneficiary area (the Alpine area for Alpine Space Program-Interreg) (

Figure 3).

The Alpine Convention is an international treaty signed by Austria, France, Germany, Italy, Switzerland, Liechtenstein, Slovenia, Monaco, and the European Union in 1995. Its goals concern the sustainable development and the protection of the Alps, as well as to preserve this territory for future generations through transnational cooperation involving national, regional and local authorities.

Being a legally binding instrument, its decisions are included in specific protocols which are mandatory for the signatory states.

On climate issues, the Alpine Convention adopted a Declaration on Climate Change in 2006, the Action Plan on Climate Change in the Alps in 2009, followed in many thematic working groups by a series of climate-relevant activities, which led to the creation of Alpine guidelines in the field of water management (including hydropower), natural hazards, and adaptation at local level. Some years ago, it published the vision “Renewable Alps” (2014) and approved the Sixth Report on the State of the Alps entitled “Greening the Economy in the Alpine Region” (2016) [

50]. In 2016, it set the objective “Tackling action on climate change” as one of the six priorities of the Multiannual Work Plan (MAP) [

51] for the period 2017–2022 and decided “to establish an Alpine Climate Board in order to bundle together existing climate change initiatives and contributions in the Alpine area and to elaborate proposals for a concrete Target System of the Alpine Convention in regard to the perspective of a “climate-neutral Alpine space” in accordance with the European and international objectives”. The Alpine Climate Board carried out a stocktake of all activities (more than 100) by all agencies in the Alpine areas. On this basis, it drafted the Alpine Climate Target System 2050, which was adopted in 2019 in the frame of the Innsbruck Declaration. Since then, the Alpine Climate Board has been focusing on the development of an updated Climate Action Plan to be adopted in 2020 and on the facilitation of the operationalisation of the Alpine Climate Target System 2050. To this effect, the Board determined an array of implementation pathways and organized a matchmaking workshop targeted at representatives of all sectors of activity in the Alps. Finally, it currently operates also together with the contracting parties, the observers, and the thematic working bodies of the Convention on cross-sectoral aspects of adaptation on the production of guidelines, workshops and experimentation projects.

EUSALP (EU Strategy for the Alpine region) is a macro-regional strategy and an integrated framework endorsed to address common challenges faced by the Alpine region by the European Council. It works for promoting cross-border cooperation in the Alpine states, identifying common goals, and implementing them more effectively. In addition to the political organisations, action groups (i.e., groups of stakeholders and change-makers) operate to better coordinate national policies and decisions. They aim at highlighting the areas where activity is already in progress—either at EU-level or in other international frameworks—but which require enhanced efforts of coordination within the Alpine Region and coherent funding strategies as a condition for success in their implementation.

Within one of these groups, the Action group 8, mountain regions discuss how to improve risk management and to better manage climate change, including major natural risks prevention. The outputs are studies, good practices, policy enhancement options on risk and adaptation policy. The same regions also coordinate efforts in common projects, like CAPA (the Climate Change Adaptation Platform for the Alps) [

53]. This platform facilitates exploration of knowledge clusters that are summarized by experts and which are significant for Alpine territories, from the local to the transnational.

The Alpine area for Alpine Space Program-Interreg is not a consolidated institution but is a European transnational cooperation programme for the Alpine region. It provides a framework to facilitate the cooperation between economic, social and environmental key players in seven Alpine countries, and between various institutional levels. Lastly, it financed seven projects related to climate issues: ALPTREES (for supporting European forests and urban areas against climate change; CaSCo (for the reduction of carbon dioxide emissions); CESBA Alps (to improve the sustainability of the Alpine built environment); GoApply (for developing national strategies and action plans on Climate Change Adaptation); GreenRisk4ALPs and OpenSpaceAlps (for the promotion of green and open areas); and SESAM (for boosting the competitiveness of Alpine dairy farming and preserving local traditions and culture).

By means of the Alpine Climate Target System 2050, the Alpine Convention fits into the national and local governance system (

Figure 4).

The decisions of both Alpine Space Program-Interreg and EUSALP are not mandatory for the regions. Relative policies should be adopted and implemented at a lower level. Initiatives, working groups or platforms are being looked at with interest, because they are trying to translate and implement European and national guidelines within homogeneous supra-regional (transnational) areas. These European or macro-regional programmes do not dictate the governance structures/instruments with which to pursue the objectives recommended by them. The choices are left to the lowest decision-making levels. For now, the preferred tools remain the drafting of a plan or a project. The first is generally a long-term and mono-sectoral document which considers only the effects produced by a single sector of activity on the climate for several years. Its adoption procedure is relatively simple as it requires just an agreement among the participants to the programmes; however, it hardly considers the cross-sectoral effects of climate change and mono-sectoral policies. The project is preferred as a tool as it has a limited duration when the activities are appropriately targeted and objectives oriented. A system for monitoring the effectiveness on the climatic conditions, a set of incentives and a penalty system are still lacking. With regard to stakeholders’ involvement, consultation of lower levels of government, associations or groups of citizens is somewhat limited to a few public instances such as working groups or conferences.

Links with existing and wider-scale strategies are constantly recommended in reports, studies and international climate change adaptation targets.

6. The Climate Adaptation Strategies and Associated Governance Structure for the Alpine Area at Regional/Provincial Levels

The Alpine area extends across eight countries (Italy, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, France, Slovenia, Monaco and Liechtenstein), 48 regions/autonomous provinces and 5700 municipalities. As such, in addition to these international institutions, national, regional, and local organisations operate for the promotion of this area (

Figure 5). The great territorial diversity and the presence of numerous institutions at several levels require specific strategies to address adaptation and local resilience to climate change.

In Austria, the responsibility for the coordination of climate policies lies with the Federal Ministry for Climate Protection, Environment, Energy, Mobility, Innovation, and Technology. These policies involve different competences at the federal and regional level. In 2019, the Austrian Federal Government drew up a comprehensive national energy and climate plan for achieving the Paris climate protection goals. This plan covers those sectors that are not subject to the EU Emissions Trading System, such as transport, agriculture, or buildings. It also includes regulations related to the tourism, energy, health, transport sectors, as well as ecosystem and biodiversity, spatial planning, and trade & industry. In the run-up to the work, a broad consultation was conducted, nearly 300 measures were included, an impact assessment was carried out, the investment needs were identified and feedback from the European Commission was incorporated.

Impact assessment demonstrates the way to achieve the objectives and was carried out by a scientific consortium consisting of the Federal Environment Agency, the Austrian Energy Agency, Vienna, and Graz Universities of Technology and WIFO. It consists of a comprehensive, data-based impact analysis that outlines the path to achieving the objectives, including the effects on the employment situation, gross domestic product, and income distribution. In terms of participation, some Austrian regions have participated in the Pilot Programme “Climate Change Adaptation Model Regions for Austria—KLAR!”, which offers a process-oriented approach for municipalities to raise awareness for climate change adaptation and implement concrete actions at the regional level. In their adaptation measures, the participating regions focus on bringing together the population and people from the affected fields of action, informing them and raising their awareness of adaptation to climate change. Wider large-scale strategies are taken into consideration, as the objectives of international treaties, European institutions and other organisations operating transnationally at Alpine level are included in all planning documents. Austrian Alpine regions contribute to harmonize the strategies and work by both a bottom-up and top-down approach, also suggesting solutions within the different working groups of the EUSALP and the Alpine Convention.

In Switzerland, for the energy and climate issues, the cantons meet at the technical level in the Conference of Cantonal Energy Offices and the Conference of Heads of Environmental Protection Agencies, and at the governmental level in the Conference of Cantonal Energy Directors and the Swiss Conference of Cantonal Directors of Public Works, Spatial Planning and the Environment. These institutions develop and coordinate the joint activities of the cantons in the field of energy and climate policy. Four regional conferences—Eastern Switzerland with Liechtenstein, Central Switzerland, North-western Switzerland, and Western Switzerland (ENFK)—enable the cantons to work closely together to define the implementation of energy and climate policy measures, the information to be disseminated and the training to be provided in the regions concerned. Recently, they have supported the efforts of the confederation in facilitating the expansion of energy supply networks in Switzerland and in border regions by simplifying authorisation procedures, without affecting the right of appeal of environmental associations and strengthening basic and advanced training programmes for consultants to building owners (planners, architects, engineers, building technicians), in collaboration with the federal authorities. However, institutional interest is confined almost exclusively to energy issues and almost none to climate issues, although the cantons’ energy policy is geared to climate protection objectives and the protection of resources. In the same period, many cantons have drawn up strategies, programmes, guidelines or planning reports on their energy and climate policy, formulating concrete targets and plans of measures. In 2020, the Federal Office for the Environment evaluated the effects of climate change abroad and the risks and opportunities for Switzerland. In this last document and in those previously mentioned, there is no specific reference to the Alpine area (covering 60% of the national territory) or to the participation of the community or other private stakeholders.

Germany has set itself ambitious climate targets. The Climate Action Plan 2050 adopted by the Federal Cabinet at the end of 2016 demonstrated the German government commitment to tackle climate change with ambitious climate policy and the implementation of the Paris Agreement measures. The plan centres on the goal of achieving extensive greenhouse gas neutrality by 2050 and of keeping global warming significantly below two degrees Celsius, or even below 1.5 degrees. The German government considers long-term strategies and facilitative dialogue as key instruments for future-oriented, reliable policy planning and for the revision or elaboration of nationally determined contributions (NDCs) of all parties in 2020 and the estimation of the economic, social, and other ecological impacts of possible measures. The Climate Action Plan 2050 provides guidance for all areas of action up to 2050 and for upcoming investments. Restructuring the energy sector is a key aspect of the plan, but it is not the only one. Building, transport, agriculture sectors, and their implications on climate conditions were considered in the plan. The programmes of measures are fleshed out in cooperation with the stakeholders in the Climate Action Alliance and civil groups, as well as in coordination with the German Bundestag. German government appoints a scientific platform comprising selected research institutions in the fields of natural and social sciences to perform these tasks. The programme plan will continue to be reviewed and updated in the future as part of a public dialogue process with broad participation by the Länder, local authorities, the private sector, civil groups, and the communities. The participation processes related to the Climate Action Plan 2050 itself will be regularly evaluated and further developed. Germany’s 2016 national climate strategy was preceded by the Climate Action Programme 2020, which was adopted by the Federal Cabinet in 2014. None of the above documents contain specific requirements for the German Alpine regions.

In France, there is the Ministry for the Ecological Transition whose general mission is to prepare and implement the government’s policy in all areas related to ecology, energy transition and biodiversity protection, and climate change. In 2017, it prepared the “Plan climate” [

68,

69]. This plan aims at drawing up future solutions through strengthening the attractiveness and scientific cooperation mechanisms in key areas to combat climate change. It attributes to the government the function to promote green and responsible finance labels, to consider how to take better account of climate risks in financial regulation. It also pays close attention to all energy issues and specifically to develop clean and accessible mobility for all, to eradicate fuel poverty in ten years, and place the circular economy at the heart of the energy transition. This plan also includes actions for mobilizing society, through the introduction of a participatory budget and the adoption of a logic of co-construction with the territorial levels of governance, including local institutions and civil society. Regarding the existing climate policies, the plan ensures the coherence of policies for adapting to changes in the national (Climate Plan 2017, territorial planning for adaptation) and international context (Paris Agreement, Global Agenda for Climate Action, European Union adaptation strategy). However, this plan does not specifically focus on French Alpine regions.

In Italy, the regions and the environment agencies represent the reference for environmental protection, climate change action, environmental data collection, technical-scientific consultancy and technical control functions, and tasks on issues related to the environment. They also develop applied research activities, training, information and education on climate change and carry out technical-scientific coordination and incentivisation activities vis à vis issues related to climate change. Specifically, the Alpine regions have adopted regional strategies and plans to address local climate challenges, and documents to guide the administration to reduce the negative impacts of climate change. The adaptation measures will be identified according to a priority criterion starting from an analysis of scientific evidence, expected scenarios and vulnerability analysis and will be integrated into sector plans and programmes in a mainstreaming process. Appropriate adaptation measures have already been adopted for some regional sector plans. The discourse of all these documents foresees the participation of different stakeholders, but the methodology for their involvement has yet to be defined in detail for all regions. Moreover, this discourse takes as a reference the National Strategy for Adaptation to Climate Change, adopted in 2015, and the National Plan for Adaptation to Climate Change whose approval process is still not definitively concluded. These documents have been thoroughly based on the involvement of stakeholders and decision-makers and on the principle of preferring mainstream adaptation across existing policies rather than introducing new ones. Important elements of reference are the documents presented at EUSALP and European level, which are reported in any strategies and plans. Their legal references include EU directives and regulations, and the accompanying national legislation. The Alpine Convention Guidelines for climate change adaptation at a local level provide a solid process overview of the main impacts, as it advises local institutions on climate adaptation and introduces criteria for the analysis of vulnerability and risk assessment.

7. The South Tyrol

South Tyrol is in the heart of the Alps and is an entirely mountainous province. The topography determines local climatic conditions and influences the formation and distribution of landscapes, watercourses, and settlements. The area benefits from the interaction of three types of climate: humid-moderate (North-West Atlantic); dry with cold winters and hot summers (continental East); and warm with wet winters and dry summers (southern Mediterranean). The Alps hinder the direct penetration of air masses, such as the Foehn (warm dry fall wind), making the region drier compared to other Alpine areas. The orientation of the slopes has a decisive effect on the irradiation conditions. Temperatures fall as the altitude increases, while precipitation intensifies. The valley systems are deeply engraved by rivers and streams, particularly from the Adige river. Most of the local population is concentrated in valleys. The pressure for land conversion for settlement and productive uses has decreased the forest cover, with consequences on the climate, particularly changes in the albedo (i.e., the ability of the surface to reflect the incoming radiation), evaporation rates and soil roughness. The “heat island” effect occurs in local larger cities, mainly caused by the greater heating of the built-up areas, reduced dispersion of evaporation and the reduction of green surfaces.

Table 3 lists climate factors and relative projected changes/impacts for South Tyrol:

These effects produce changes and impacts on different sectors.

Table 4 lists them.

South Tyrol is part of EUSALP and the Interreg Alpine Space and has signed the Alpine Convention. It is an autonomous province and, compared to other Italian provinces and regions, has greater autonomy in many matters, including those relating to climate protection. This autonomy has been recognised by the Italian Constitution because of its history, multilingualism, and the presence of people from different cultural and national backgrounds. It is a province, and it is a distinct and autonomous entity with respect to the region; however, it exercises powers and functions that are proper to a region. In particular, it exercises legislative competence (and this is the most important difference compared to the other Italian provinces, which have only regulatory competence, in a very circumscribed field of subjects): it therefore passes laws in the most important sectors of local social and economic life, within a wide range of competences assigned by the statute and carried out in the application rules. Constantly over the last decades, in accordance with the concept of autonomy that is not static but dynamic, i.e., aimed at a progressive expansion of the exercise of self-government, additional competences have been conferred on South Tyrol, usually in the form of delegation, in addition to supplementing and updating the application rules already issued. The process of extending autonomy is ongoing and discussions with the State on the transfer of further competences to the province, such as those relating to tax agencies or the administration of justice, are currently taking place in the appropriate fora. Together with Trentino (IT) which has a similar level of autonomy, it is the only province in the Alpine area. In addition to the three above-mentioned European experiences, South Tyrol also participates in EUREGIO, another international organization with Trentino and Tyrol (AT).

8. The Governance of Climate Issues in South Tyrol

At national level, the Italian climate adaptation strategy highlights the vulnerability of the entire Alpine area and promotes the production of more reliable climate change scenarios. It detects the critical situation of the three-times-higher increase in temperatures in the Alpine territory, its impacts on the precipitation distribution, snow cover duration and the reach of glaciers. The strategy evidences the higher vulnerability to a wide spectrum of natural risks and the growing demographic and environmental pressure on these regions, and it proposes an analysis of the climatic impacts on the mountain hydrographic basins and water reserves (glaciers, snow). However, none of these measures are specifically targeted for South Tyrol. A process is currently underway to upgrade regional and municipal planning structures and methods concerning mitigation and adaptation. The process is promoted by the European Commission and has references to some examples of beneficial coordination between municipalities (e.g., the Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy). It will become a strategic reality by 2030 with the Sustainable Energy and Climate Action Plan (SECAP).

Recently, the Second Report on Natural Capital (2018) [

71] strengthens awareness on the theme of Natural Capital and its integration in political decision-making processes. However, this report addresses the entire Alpine eco-region and not just South Tyrol. With reference to this region, it focuses on the effects on soil fertility loss, fragmentation of natural resources, and forest management by suggesting the realisation of green infrastructures along the main valleys, about the Eastern Alps. In addition, it mentions the need to focus on the revitalisation of water bodies to improve the ecosystem services of this landscape element. Although it highlights the importance of these measures to address the climate challenges for the Alpine area, it includes just recommendations and not concrete actions.

South Tyrol has not adopted a long-term and concerted strategy for climate adaptation actions and has not promoted other forms of systematisation of sectoral policies.

The most important strategy paper for climate change adaptation is the Climate Plan Energy South Tyrol 2050 [

72], which implements the national energy strategy on a provincial scale. The strategy is a sort of roadmap that describes the path to be followed to transform the area into a real “Climate-Land”, a model for the protection of climate and biodiversity in the Alps. It is inspired by the UN General Assembly resolution (UN, A/Res/62/196, 2008) [

73] that assumes: “Sustainable mountain development is a key component for achieving the Millennium Development Goals in many regions of the world”. Similarly, it takes into account the Report of the UN Conference on Sustainable Development [

74] that reiterated this concept and the need to develop adequate mitigation measures for mountain regions.

By enhancing the ability of local authorities and private operators to shape integrated energy and climate strategies, this document suggests some measures to reduce CO

2 emissions, promotes renewable energies and the adoption of other energy efficiency measures by 2050. These measures are in line with “Strategia Energetica Nazionale” (National Energy Strategy) regulations that define the development scenario of the energy sector in 2030 by incentivising energy efficiency and the use of renewable resources as well as encouraging the decarbonisation process with climate-changing emissions reduction targets of 39% by 2030 and 63% by 2050 [

75]. Despite its goal to empower local, public and private operators, to implement sustainable energy and climate strategies, this plan focuses on the past and future implications of climate change just as a direct consequence of energy policies. The effects produced by other economic activities are just marginally mentioned. For these reasons, it cannot be considered as a general policy framework for the future. However, its elaboration has constituted a recent example of collaboration among public and private actors. It is, in fact, drafted by the Province of Bolzano together with BOKU University and the CasaClima Agency. The setting of intermediate objectives and the obligation to renew and translate the new knowledge into concrete measures derived from technological innovations or changed framework conditions make the plan innovative and in line with the need to review the decisions previously periodically taken.

Climate issues are also considered in some sectoral plans, but marginally.

The local RDP (rural development programme) provides for some financial contributions to support farmers who adopt extensive agronomic practices compatible with biodiversity and with lower levels of carbon dioxide, methane, and nitric oxide emissions. This adopted approach for addressing climate vulnerability is mono-sectorial and based on a dual governance mechanism. In fact, it does refer specifically just to one economic sector (agriculture), does not assume any intercorrelated and indirect effects on other economic sectors. It also strengthens the links to just one institution (the Province that allows the financial contribution) and the beneficiary firms and does not include any reference to local urban gardens [

76,

77].

The Urban Mobility Plan 2020 [

78] includes measures to reduce CO

2 emissions and promote the use of ecological transport. These measures are part of the provincial measures package Green Mobility to foster sustainable mobility in the Province of Bolzano and to create a model for sustainable Alpine mobility [

79]. They are financed by provincial financial resources and are a good example of intermunicipal cooperation. The plans and these measures are inspired by general and previously shared aims in line with provincial and sectoral plans in terms of mobility and economic development. They also have considered demographic dynamics. Climate variations are just considered as an indirect consequence of their implementation and not a driver factor.

Although tourism is an important economic sector for the South Tyrol, the relevant strategy document does not contribute to design a legal framework for climate protection or an adaptation strategy [

80]. It highlights the importance of snowfall: its reduction leads to a contraction of the winter season and a greater use of artificial snow, the production of which has a significant environmental impact. It points out that the increase in summer temperatures in urban centres at lower altitudes leads tourists to move to other, more elevated places at higher altitudes. This shift forces the traditional tourist localities to reformulate their touristic offers, while the places to which the new preference of tourists is directed must be equipped with new facilities, whose development has further impacted on the surrounding environment. Likewise, the snow concentration or high temperatures in some periods lead to overtourism. Although demonstrating all possible climate impacts, the strategy paper does not make recommendations for climate protection in the tourism sector, does not give indication of concrete policies or include any specific considerations about transport connectivity impacts on the accessibility of touristic centres.

Some years ago, the Provincial law n.17/2017 introduced in the decision-making phase the obligation to consider the effects on the environment of provincial plans and programmes. This is a direct implementation of some laws adopted previously at national level and obliges provincial departments to evaluate possible impacts of the adopted measures in economic, social terms, but also in climate and natural ones. This impact evaluation was not mandatory and only a few departments adopted it in the legislative process. However, this is still an ex-ante evaluation, i.e., carried out before the law enters into force. There are no mechanisms to date that assess the environmental impacts and climate of laws ex post, i.e., after a certain period of coming into force. In some documents, these aims are considered as preamble or general principles or do not include specific actions to achieve them. They lack a monitoring system to verify periodically the achievement of relative goals.

In 2020, the Joint Research Centre Covenant of Mayors of the European Commission approved the PAESC (Action Plan for Sustainable Energy and Climate) of the Municipality of Bolzano, which had already been well-received by the City Council last May. The Plan is the result of a long study carried out with the internal resources of the Municipality, in particular of the Geology, Civil Protection and Energy Office, and it follows the City Council resolution of 2017, with which the City of Bolzano decided to join the Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy.

The climate governance in South Tyrol is composed of the Province of Bolzano (with initiatives, regulatory and planning power and competence), the agency for the civil protection, Kasaclima, Ökoinstitut, Federazione protezionisti Sudtirolesi and Eurac Research (for scientific and thematic consultations).

The most active participants are the provincial departments. The coordination of their actions is limited and does not take place within periodic meetings or coordination programmes. Coordination between Province and local municipalities is also difficult. Even if they adopt sectoral plans and some of them also adopt climate plans, their decisions do not merge into a unitary document at the provincial level. The result is the drafting of sectoral plans or legislative proposals that are not integrated with each other. In addition, individual projects or adaptation actions are carried out, but their impacts are often considered insufficient. The involvement of private associations or citizens is rather limited. The most active private association is the Ökoinstitut, which deals with the topic of climate protection. This institute collaborates with and supports the province and communities to develop measures for better energy efficiency or more sustainable transport; it collaborates with private companies to optimize their energy consumption and achieve more careful handling of resources. It also supports private and public bodies in planning green events, which are events that are planned, organised, and implemented according to sustainability criteria, including the use of sustainable products, energy efficiency, local value creation and waste management.

9. Discussion

Climate change governance in the Alpine area includes macro-regional/European actors (EUSALP, Alpine Convention, the Alpine area for Alpine Space Program-Interreg), national ones (national states) and regional/provincial actors (the regions and the provinces), which differently operate, formulate and implement climate adaptation strategies.

At the European and national level, the policies and strategies define specific aims and targets and policy guidelines for the whole Alpine area, specifically ignoring the South Tyrol and other Alpine regions in detail.

This offers an inclusive view of all territories, which does not take sufficient account of the different climatic conditions or the climate change adaptation needs of the Alpine regions. The Alpine Convention acts include data and future scenarios about the entire area, as well as policy guidelines. Only recently, it has opened the discussion to the several agencies which operate on climate issues within a multi-participatory committee. Like EUSALP decisions, the Alpine Convention acts do not specify the systems with which to pursue the objectives recommended by them. The implementation choices are left to lower decision-making levels. For now, the preferred tools remain the drafting of a plan or a project. At the national level, all Alpine countries adopt a general framework for climate policies, sometimes with a specific act, other times together with decisions about energy policies. At a lower administrative level, provincial documents include measures intended to reach the fixed targets at European and national level or include some specific recommendations directly suggested by wider policies. Devolution of power was implemented in all considered countries. Referring to Sapiains et al. [

7] and their clustering of climate adaptation governance, different models adopted in the European countries can be included among the clusters considered. The governance structure adopted at Alpine level by the three international institutions refer to the first cluster; it can be assimilated to a multi-governance system where different players are included in a broader scheme. At the level of the single state, the majority of European countries could be included in the second cluster, as they attribute great importance to the role of the state in climate policy formulation and implementation. However, some elements suggest that there is an ongoing transformation towards the third and the fourth clusters where the role of subnational initiatives is more relevant. Two countries, Austria and Italy specifically promote examples of transformative and experimental approaches at the regional level. This is true also for South Tyrol where some characteristics of the first cluster (the essential role of the government and in this case of the provincial government, in addition to the plurality of players, specifically) and of the new narratives with local communities and city networks (of the fourth cluster) merge with the element of innovation typical of the last cluster.

Climate change governance in South Tyrol includes national and macro-regional/ European players (Italian government, EUSALP, Alpine Convention, the Alpine area for Alpine Space Program-Interreg), provincial players (the Province of Bolzano), which operate, formulate and implement climate adaptation strategies differently.

The Climate Plan Energy South Tyrol 2050 is based on European and national plans, guidelines and benchmarks on CO2, energy issues. However, many local stakeholders believe that Italian and European policies are not region-specific and therefore they are unable to adequately consider the local climate conditions. Contrarily, the regulations included in provincial documents refer specifically to the provincial territory, and the inefficiency of some of them demonstrate that the province or the municipality are not the optimal territorial areas for the correct implementation of climate policies—as the climate of South Tyrol is heavily influenced by its geographical position in the heart of the Alps. As such, they hypothesize that these policies could be more effective if implemented at the wider Alpine scale.

Devolution of power from central to local governments leads to great autonomy for the province, compared to the national state. This implies that this province is free to adopt more territorial-targeted policies that can best meet the needs and characteristics of the territory. However, the adoption of such policies can generate territorial disparities with territories located in other neighbouring Italian regions that do not benefit from the same degree of autonomy. This could also make coordination between the same Italian regions and autonomous provinces difficult for the formulation of common policies.

Sharing power and responsibilities among bodies interested in climate issues is not so evident in South Tyrol as the participation of local associations or private individuals in decisions vis à vis this field is limited. This prevents the acquisition of different and bottom-up suggestions. Finally, adhering to the three international coordination mechanisms already mentioned, South Tyrol loses part of its sovereignty. However, because the acts produced at this international level are just recommendations or project proposals, South Tyrol remains free to decide extensively its policies on climate issues, without incurring penalties. Power distribution is balanced in favour of the province, with scarce possibility to promote local initiatives and foster best practices adoption at the local level.

Differences in spatial, time and sectoral scales make it difficult to adopt general or multi-disciplinary plans or long-term strategies at the provincial level. Unlike other Alpine regions, South Tyrol lacks general and transversal climate policy. The 2050 Climate-Energy strategy is not divided into integrated local actions and does not contain planning and sectorial policies for sustainable development; it merely explains measures to reduce pressures and over-exploitation of natural energy resources and promotes the use of innovative technologies and methods for renewable energies. Only the RDP promotes the implementation of measures aimed at reducing the hydro-geological risk, preventing erosion, and improving land and water management, according to a multi-sector approach. However, this approach is not used for actions to support rural development at the local level. Other sectors, such as tourism and transport, do not provide for coordinated actions; rarely, they assume specific actions limited to singular projects. This implies limited knowledge about the reciprocal influence of each economic sector on climate issues as well as scarce opportunities to implement coordinated actions; these impediments are common among the sectors.

The absence of a general and multi-sector strategy is probably due to the difficulty of coordinating the high number of players involved as well as the scarce collaboration among provincial departments. These factors inhibit a general, multi-annual policy framework that could inspire annual policies and monitor climate change in the long term.

10. Conclusions

This article describes the climate governance system existing in the Alpine regions and specifically in South Tyrol and the adaptation strategies to address climate challenges. No comparative study has been carried out, nor has a specific study on South Tyrol been done recently. The findings of the present study are therefore relevant.

A framework strategy at Alpine or provincial level does not exist. The few prescriptions on climate issues are included in mono-sectoral plans related just to the administered territories. The participation of local bodies is not incentivized and limited to just a few initiatives. Although important, interactions across Alpine, national, and sub-national policy domains are limited. To obtain a comprehensive overview of the current changes as well as to validate the models used for the scenarios, developing and strengthening the measurement networks of climatic parameters—not just in South Tyrol, but in all remote mountain alpine regions—should be encouraged. A better definition of the territorial framework of policies is not the only effective mechanism for addressing the specific challenges of climate in this region. The definition of responsibilities of local institutions and their involvement is another key issue of fundamental importance, underestimated in South Tyrol, but planned in the other Alpine regions. Similarly, the incentives to coordinate strategies and actions at the sub-national level (among different regions, including those belonging to different states, but with similar climatic conditions) should be encouraged, but currently, it is not considered a crucial policy option. This uncertainty makes it difficult to define a long-term strategy which, by contrast, has been adopted in some Alpine countries only at national level without taking territorial specificities into account. Coordination between the various players and the clear allocation of their competences is therefore more urgent than ever.

However, the urgency to study the impacts of climate change on human activities and to mitigate their effects requires consideration of long-term adaptation policies that are transversal to all sectors of activity. As such, the improvement of knowledge and an appropriate system for its dissemination, and the definition of a dedicated plan are essential. The next research would be focused on the analysis of existence and strength of connections between the various bodies, and their embeddedness in the broader socio-economic network, through social network analysis techniques. Furthermore, they could explore new methods to promote the integration of some supply chain sectors into the overall network, as well as to monitor the effectiveness of the plan or the project on the climatic conditions and the introduction of a penalty system.

The paragraph “The governance of climate issues in South Tyrol” was written considering the results of the European project ESPON Bridges.