Good Idea But Not Here! A Pilot Study of Swedish Tourism Stakeholders’ Perceptions of Halal Tourism

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- What knowledge is there in Sweden, especially in the tourism industry, about Halal tourism?

- (2)

- How do tourism stakeholders perceive a possible marketing of Sweden as a Halal tourism destination as well as opportunities and challenges that exist in this regard?

2. Research Context

3. Literature Review

3.1. Definition and Attributes

3.2. Impact

3.3. Challenges

3.4. Research Synthesis

4. Methodology and Data Collection Procedure

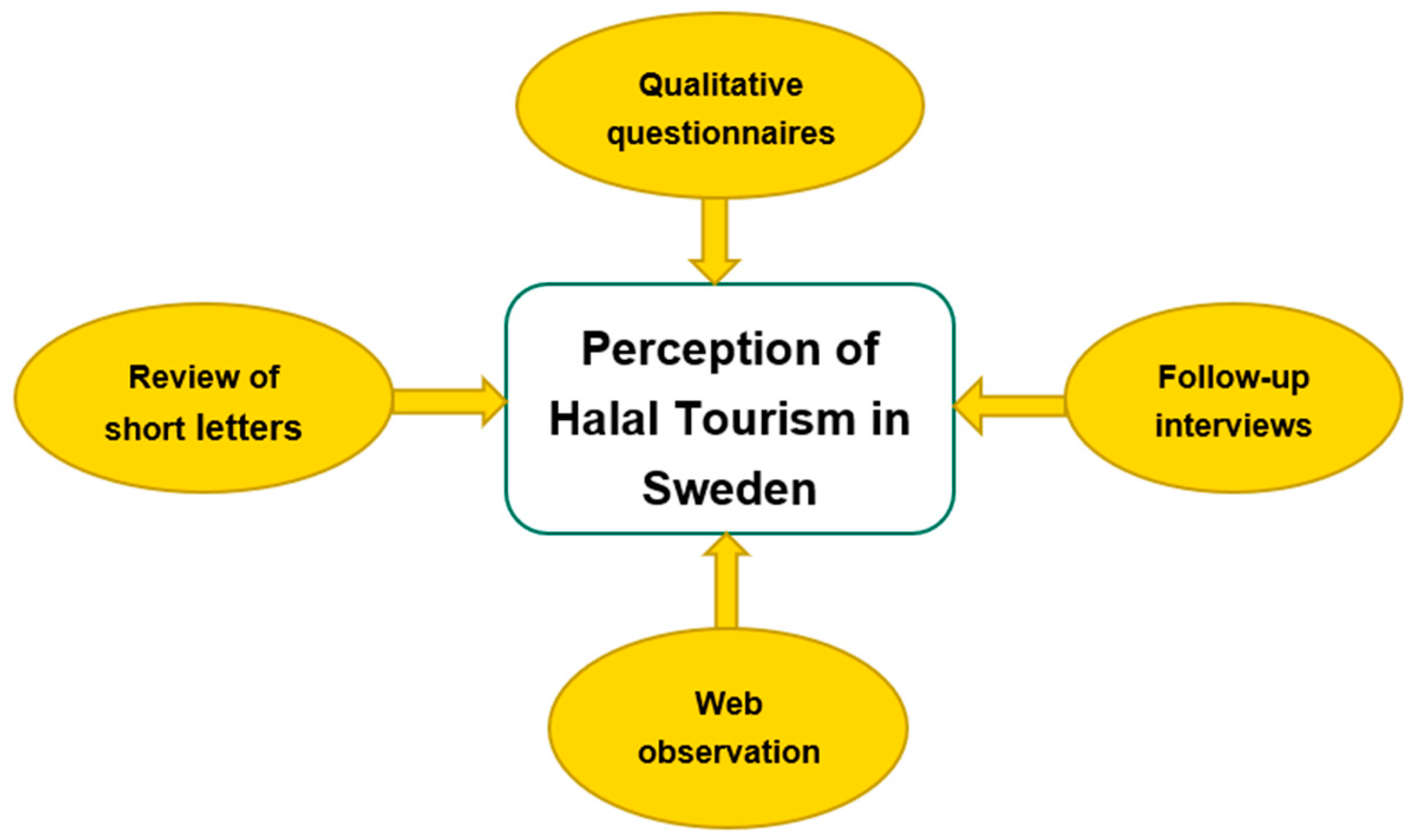

- Between June 2018 and June 2020, a questionnaire was sent through email (as an attached Worddocument) out to 258 persons in government, organizations and enterprises with a connection to the Swedish tourism industry. The reason behind this variation of workplaces was to get a broader perspective, and this method was chosen because of the ease of the method and its time and cost-effectiveness. The questionnaire contained 15 semistructured questions; five questions on demographic/background issues (Table 1) and the rest were core questions that required explanations and justifications. In the questionnaire the author gave initially a basic definition of Halal tourism, namely absence of gambling, alcohol and pork in the service, to facilitate for the interviewees. Ultimately, and after four reminders, only 25 persons sent completed questionnaires. With some exceptions, most respondents gave answers to all questions.

- The author also received 21 letters from the email recipients (henceforth recipients) who reasoned why they would not participate. Still, the author chose to include these letters in the analysis since they contained partly valuable information.

- A web observation in July 2020 by the author.

- A follow up interview in autumn 2020 with four of the respondents to get an even deeper insight. These interviews were conducted on Zoom and took 30 min/each on average.

Data Analysis

5. Findings and Analysis

5.1. Short Results of the Empirical Data

5.2. Low Knowledge of the Issue

“I had never heard the expression before I received your email, so I had no definition.”

“I, who have been in the industry for 20 years, cannot see that there has been any major discussion on it.”

5.3. Challenging Adaptation

“I believe that there is a great need to raise awareness and knowledge about Halal tourism in general, in Sweden.”

“Disadvantages—negative publicity seen from people’s ignorance and prejudices. Controversial for some, I think.”

“The disadvantage is that you need to adapt many businesses for this to become developed.”

“…. it is difficult to lay prayer rugs in our historic environments ……. Today we have a lack of space so it can be difficult to find prayer rooms that are available every day……. Food management is problematic as we still want to offer Swedish food above all…... It is important to train the staff and ensure that the adaptation works in everyday life.”

5.4. Uncertainty about the Economic Impact

“I think the adaptation should be in proportion to what you get out of this. If a company must build completely new kitchens, adapt spaces and hire knowledgeable people who will then take care of two groups per year, we may not have used our resources properly.”

“If Halal tourism means that no games, alcohol or pork may be served in the presence of these visitors, I think it is very unlikely that anyone in Sweden would see it as business potential to target these customers.”

“No, it is unprofitable from the beginning. Partly because of the need for investments in separated bathing facilities, partly because there is no income from alcohol and partly because it is culturally contradictory Swedish values.”

5.5. Cultural Impact: Scenarios of Fear

“Depending on degree of adaptation, polarization, i.e., the requirements are large enough to influence the requirements of other guests. Absence of pork no problems, games and gambling neither, nor (for me) absence of sales of alcohol. But for example, if other guests are not allowed to use their own wine in their rooms or on the terrace, it can be a problem for me too. Also risk of argument for extremists’ mantra of “Islamization”.”

“Absolutely, but only to the extent that it does not reduce the quality for the rest of the tourists…”

“I think that some ethical dilemmas can arise just in view of ideas about gender equality and the equal value of the genders that are worth considering if one decides to market Halal tourism.”

“…., it can easily end up in the teeth of those who have xenophobic views (media and extremist parties).”

“... clashes with our view of gender equality. We are the world’s most secular country, we are a leader in LGBTQ issues…”

“Sometimes there is criticism of both Halal and Kosher slaughter, which is a risk for companies that offer these services (hotels, shipping companies, incoming agencies, etc.)-if any group were to start demonstrating against the phenomenon, for example.”

5.6. A Possible Optimal Balance

“If one is looking for facilities that only strive to receive “Halal guests”, it is a boring development, I prefer to create arenas to meet no matter what one wants in his/her glass or on his/her plate—here we try to meet and respect everyone regardless of desire.”

“Personally, I think all customers’ wishes and needs should be met as far as possible, aslong as it does not “affect” other customers. In other words, it is totally okay to have a prayer room, serve Halal food as a special diet, pick out alcohol from minibars, etc. to individual customers who want this, but I doubt that in Sweden they may invest in special facilities where all guests should have this.”

“I guess there is a sliding scale of what needs a “Halal tourist” might have. On one extreme, there are perhaps the more orthodox Muslims who live the Qur’an more profoundly and thus, would have previously described needs for separate beaches, bathing times, etc. On the other hand, I see that there would be a large proportion of “Svensson Muslims” who have a more open attitude to Halal and above all would appreciate, for example, hotel that offer Halal-adapted food and drink, which would make the visit/everyday life easier.”

“For Muslim tourists, two basic aspects are particularly concerned: Halal food in restaurants and dignified conditions for religion practice in accordance with the standards ……. Halal tourism is not about “adapting ourselves to receive radical Islamists”, it is instead about creating and adapting a range of products and services that considers different cultures.”

5.7. Confusion over Marketing

“In the overall marketing of Sweden as a destination abroad, we focus on a large group of travelers who are curious about new destinations such as Sweden, primarily in nine countries in the world. Therefore, we do not have any specific knowledge about this area—yet.”

“I believe that destinations in Muslim regions have an advantage that can be difficult to compete with and that the target group for various reasons chooses these destinations over, for example, Sweden.”

“Do not think markets but target groups—it is more effective that way.”

“Halal is not about geography/market but a target group.”

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Implications and Limitations

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Razalli, M.R.; Abdullah, S.; Hasan, M.G. Developing a Model for Islamic Hotels: Evaluating Opportunities and Challenges. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Knowledge, Culture and Society 2012 (ICKCS 2012), Jeju Island, Korea, 29–30 June 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H.; Al-Ansi, A.; Olya, H.G.T.; Kim, W. Exploring halal-friendly destination attributes in South Korea: Perceptions and behaviors of Muslim travelers toward a non-Muslim destination. Tour. Manag. 2019, 71, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogan, E.; Sariisik, M. Halal tourism: Conceptual and practical challenges. J. Islam. Mark. 2019, 10, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samori, Z.; Salleh, N.S.M.D.; Khalid, M.M. Current trends on Halal tourism: Cases on selected Asian countries. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 19, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladiqi, S.; Wardhani, B.; Wekke, I.S.; Abdur Rahim, A.F. Globalization and the rise of cosmopolitan shariah: The challenge and opportunity of Halal tourism in Indonesia. Herald NAMSCA 2018, 1, 904–907. [Google Scholar]

- Ghazzi, O.A.; Kraidy, M.M. Neo-Ottoman Cool 2: Turkish Nation Branding and Arabic-Language Transnational Broadcasting. Int. J. Commun. 2013, 7, 2341–2360. [Google Scholar]

- Spain: Halal Tourism Conference Attracts Hotel Experts. 2014. Available online: https://halalfocus.net/spain-halal-tourism-conference-attracts-hotel-experts/ (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Religious Composition by Country, 2010–2050. 2020. Available online: https://www.pewforum.org/2015/04/02/religious-projection-table/2020/number/all/ (accessed on 8 July 2020).

- Jacob, F. These Are All the World’s Major Religions in One Map. 2019. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/03/this-is-the-best-and-simplest-world-map-of-religions (accessed on 8 July 2020).

- BNP Per Invånare. 2020. Available online: https://www.globalis.se/Statistik/BNP-per-invaanare (accessed on 8 July 2020).

- Vargas-Sanchez, A.; Moral-Moral, M. Halal tourism: State of the art. Tour. Rev. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J.C. Muslim travellers, tourism industry responses and the case of Japan. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2016, 41, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J.C. Halal food, certification and halal tourism: Insights from Malaysia and Singapore. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 19, 160–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.J.; Akbaba, A. The potential of Halal Tourism in Ethiopia: Opportunities, Challenges and Prospects. Int. J. Contemp. Tour. Res. 2018, 1, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, S. Managing Halal Knowledge in Japan: Developing Knowledge Platforms for Halal Tourism in Japan. Asian J. Tour. Res. 2017, 2, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanin, O.; Sriprasert, P.; Abd Rahman, H.; Don, M.S. Guidelines on Halal Tourism Management in the Andaman Sea Coast of Thailand. J. Econ. Bus. Manag. 2015, 3, 791–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suharko, S.; Khoiriati, S.D.; Krisnajaya, I.M.; Dinarto, D. Institutional conformance of Halal certifi cation organisation in Halal tourism industry: The cases of Indonesia and Thailand. Tour. Rev. 2018, 66, 334–348. [Google Scholar]

- Razzaq, S.; Hall, C.M.; Prayag, G. The capacity of New Zealand to accommodate the halal tourism market- Or not. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 18, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan-Hassan, W.M.; Awang, K.W. Halal Food in New Zealand Restaurants: An Exploratory Study. Int. J. Econ. Manag. 2009, 3, 385–402. [Google Scholar]

- Mutsikiwa, M.; Basera, C.H. The Influence of Socio-cultural Variables on Consumers’ Perception of Halal Food Products: A Case of Masvingo Urban, Zimbabwe. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2012, 7, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hall, M.C. Is Halal the New Nordic Cuisine? The Significance of the Contemporary Globalisation of Foodways for Food Tourism and Hospitality. Extended abstract. In Book of Abstracts, Proceedings of the Tomorrow’s Food Travel (TFT) Conference, Gothenburg, Sweden, 8–10 October 2018; University of Gothenburg: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ehle, D. Halalturism och Kosherturism. 2018. Available online: https://motargument.se/2018/08/07/halalturism-och-kosherturism/ (accessed on 8 July 2020).

- Lorentz, E. Danmark Rankat Lågt Inom Halalturism—Sverige Toppar Listan i Norden. 2018. Available online: https://nyheteridag.se/danmark-rankat-lagt-inom-halalturism-sverige-toppar-listan-i-norden/ (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Reimers, E. Secularism and Religious Traditions in Nonconfessional Swedish Preschools: Entanglements of Religion and Cultural Heritage. Br. J. Relig. Educ. 2020, 42, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Sweden/SCB. Utrikes Födda Samt Födda i Sverige Med en Eller Två Utrikes Födda Föräldrar Efter Födelseland/Ursprungsland, 31 December 2018, Totalt. 2020. Available online: www.scb.se (accessed on 1 July 2020).

- Bilden av Sverige Utomlands 2018-Årsrapport Från Svenska Institutet. 2020. Available online: https://si.se/app/uploads/2019/02/si_rapport_sverigebild_web_low.pdf (accessed on 8 July 2020).

- Nyorden 2017: Vad Betyder “Plogga” och “Omakase”? 2017. Available online: https://www.svd.se/nyorden-2017-vad-betyder-plogga-och-omakase (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- France Most Popular European Travel Destination for Muslims. 2014. Available online: https://halalfocus.net/france-most-popular-european-travel-destination-for-muslims/ (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Tillväxtverket. Antal Gästnätter Fördelat efter Hemland/Marknad (Nights Spent and Visitors’ Country of Residence). 2020. Available online: https://tillvaxtverket.se/statistik/vara-undersokningar/resultat-fran-turismundersokningar/2020-02-06-gastnatter-2019.html (accessed on 21 August 2020).

- Tillväxtverket. Fakta om Svensk Turism 2018; Tillväxtverket: Stockholm, Sweden, 2019; Available online: https://tillvaxtverket.se/vara-tjanster/publikationer/publikationer-2019/2019-06-18-fakta-om-svensk-turism-2018.html (accessed on 21 August 2020).

- Cohen Ioannides, M.W.; Ioannides, D. Global Jewish tourism-Pilgrimages and remembrance. In Tourism, Religion and Spiritual Journeys; Timothy, D.J., Olsen, D.H., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 156–171. [Google Scholar]

- Moira, P.; Mylonopoulos, D.; Vasilopoulou, P. Food Consumption during Vacation: The Case of Kosher Tourism. Int. J. Res. Tour. Hosp. 2015, 1, 9–22. [Google Scholar]

- Chieh Lu, A.C.; Gursoy, D.; Del Chiappa, G. The Influence of Materialism on Ecotourism Attitudes and Behaviors. J. Travel Res. 2016, 55, 176–189. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, T.; Chandrasekaran, U. Halal Marketing: Growing the Pie. Int. J. Manag. Res. Rev. 2013, 3, 3948. [Google Scholar]

- Shaari, J.A.N.; Khalique, M.; Malek, N.I.A. Halal Restaurant: Lifestyle of Muslims in Penang. Int. J. Glob. Bus. 2013, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Shaari, J.A.N.; Khalique, M.; Aleefah, F. Halal Restaurant: What Makes Muslim In Kuching Confident? J. Econ. Dev. Manag. IT Financ. Mark. 2014, 6, 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Haq, F.; Wong, H.Y. Is spiritual tourism a new strategy for marketing Islam? J. Islam. Mark. 2010, 1, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, R. Towards a High-quality Religious Tourism Marketing: The case of Haji Service in Saudi Arabia. Tour. Anal. 2012, 17, 509–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Gohary, H. Halal tourism, is it really Halal? Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 19, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kana, A.G. Religious Tourism in Iraq, 1996–1998: An Assessment. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2011, 2, 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- Ariyanto, A.; Chalil, R.D. The Role of Intellectual and Spiritual Capital in Developing Halal Tourism. In Proceedings of the 7th Annual International Conference (AIC) Syiah Kuala University and The 6th International Conference on Multidisciplinary Research (ICMR) in conjunction with the International Conference on Electrical Engineering and Informatics (ICELTICs) 2017, Banda Aceh, Indonesia, 18–20 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Duman, T. Value of Islamic Tourism Offering: Perspectives from the Turkish Experience. In Proceedings of the World Islamic Tourism Forum (WITF 2011), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 12–13 July 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kovjanic, G. Islamic Tourism as a Factor of the Middle East Regional Development. Turizam 2014, 18, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carboni, M.; Perelli, C.; Sistu, G. Is Islamic tourism a viable option for Tunisian tourism? Insights from Djerba. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2014, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani-Farahani, H.; Henderson, J.C. Islamic tourism and managing tourism development in Islamic societies: The case of Iran and Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2010, 12, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battour, M.; Ismail, M.N. Halal Tourism: Concepts, practices, challenges and future. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 19, 150–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsin, A.; Ramli, N.; Alkhulayfi, B.A. Halal Tourism: Emerging opportunities. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 19, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battour, M.; Hakimian, F.; Ismail, M.; Bogan, E. The perception of non-Muslim tourists towards halal tourism: Evidence from Turkey and Malaysia. J. Islam. Mark. 2018, 9, 823–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Callanan, M. The “Halalification” of tourism. J. Islam. Mark. 2017, 8, 558–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingett, F.; Turnbull, S. Halal holidays: Exploring expectations of Muslim-friendly holidays. J. Islam. Mark. 2017, 8, 642–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J.C. Sharia-compliant hotels. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2010, 10, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oktadiana, H.; Pearce, P.L.; Chon, K. Muslim travellers’ needs: What don’t we know? Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 20, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, J.; Scott, N. Muslim world and its tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 44, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeaheng, Y.; Al-Ansi, A.; Han, H. Halal-friendly hotels: Impact of halal-friendly attributes on guest purchase behaviors in the Thailand hotel industry. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 729–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elaziz, M.F.; Kurt, A. Religiosity, consumerism and halal tourism: A study of seaside tourism organizations in Turkey. Tourism 2017, 65, 115–128. [Google Scholar]

- Ghadami, M. The role of Islam in the tourism industry. Elixir Mgmt. Arts 2012, 52, 11204–11209. [Google Scholar]

- Bastman, A. Lombok Islamic Tourism Attractiveness: Non-Moslem Perspectives. Int. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2018, 7, 206–210. [Google Scholar]

- Dawood, S.R.S.; Leng, K.S.; Yusof, N. Regional Halal Clusters in the NCER Region: Revisiting the Role of Institutional Thickness. Int. J. Environ. Soc. Space 2014, 2, 47–60. [Google Scholar]

- Fithry, S.; Anwar, S. An Evaluation of Halal Tourism Program in East Lombok Regency Using Kirkpatrick’s Mode. Sumatra J. Disaster Geogr. Geogr. Educ. 2018, 2, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moldakhmet, B.; Nassimova, G.; Asan, A.B.A. Islam in Kazakhstan: Modern Trends and Stages of Development. Int. J. Soc. Manag. Econ. Bus. Eng. 2012, 6, 152–155. [Google Scholar]

- Gilani, M.K.Z.; Monsef, S.M.S. Strategic Planning for Halal Tourism Development in Gilan Province. Iran. J. Optim. 2017, 9, 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Rhama, B.; Alam, M.D.S. The Implementation of Halal Tourism in Indonesia National Park. In Proceedings of the Advances in Economics, Business and Management Research (AEBMR), International Conference on Administrative Science (ICAS 2017), Makassar, Indonesia, 20–21 November 2017; Volume 43, pp. 48–53. [Google Scholar]

- Isa, S.M.; Chin, P.N.; Muhammad, N.U. Muslim tourist perceived value: A study on Malaysia Halal tourism. J. Islam. Mark. 2018, 9, 402–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardi, Y.; Abror, A.; Trinanda, O. Halal tourism: Antecedent of tourist’s satisfaction and word of mouth (WOM). Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 23, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tama, H.A.; Voon, B.H. Components of Customer Emotional Experience with Halal Food Establishments. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 12, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.C.; Li, I.J.; Yen, S.Y.; Sher, P.J. What Makes Muslim Friendly Tourism? An Empirical Study on Destination Image, Tourist Attitude and Travel Intention. Adv. Manag. Appl. Econ. 2018, 8, 27–43. [Google Scholar]

- Abror, A.; Wardi, Y.; Trinanda, O.; Patrisia, D. The impact of Halal tourism, customer engagement on satisfaction: Moderating effect of religiosity. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 24, 633–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battour, M.; Battor, M.; Bhatti, M.A. Islamic attributes of destination: Construct development and measurement validation, and their impact on tourist satisfaction. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2013, 16, 556–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Moghavvemi, S.; Thirumoorti, T.; Rahman, M.K. The impact of tourists’ perceptions on halal tourism destination: A structural model analysis. Tour. Rev. 2020, 75, 575–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ansi, A.; Han, H. Role of halal friendly destination performances, value, satisfaction, and trust in generating destination image and loyalty. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2019, 13, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Rana, M.S.; Hoque, M.N.; Rahman, M.K. Brand perception of halal tourism services and satisfaction: The mediating role of tourists’ attitudes. Int. J. Tour. Sci. 2019, 19, 18–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasul, T. The trends, opportunities and challenges of halal tourism: A systematic literature review. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2019, 44, 434–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battour, M.; Ismail, M.N.; Battour, M. The Impact of Destination Attributes on Muslim Tourist’s Choice. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2011, 13, 527–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battour, M.; Ismail, M.N.; Battor, M.; Awais, M. Islamic Tourism: An empirical examination of travel motivation and satisfaction in Malaysia. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 50–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.K.; Zailani, S. The effectiveness and outcomes of the Muslim-friendly medical tourism supply chain. J. Islam. Mark. 2017, 8, 732–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.K.; Zailani, S.; Musa, G. The perceived role of Islamic medical care practice in hospital: The medical doctor’s perspective. J. Islam. Mark. 2018, 9, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junaidi, J. Halal-friendly tourism and factors influencing halal tourism. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2020, 10, 1755–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alina, A.R.; Rafida, A.R.N.; Syamsul, H.K.M.W.; Mashitoh, A.S.; Yusop, M.H.M. The Academia’s Multidisciplinary Approaches in Providing Education, Scientific Training and Services to the Malaysian Halal Industry. Middle-East J. Sci. Res. 2013, 13, 79–84. [Google Scholar]

- Razalli, M.R.; Abdullah, S.; Yusoff, R.Z. Is Halal Certification Process “Green”? Asian J. Technol. Manag. 2012, 5, 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Saad, H.E.; Ali, B.N.; Abdel-Ati, A.M. Sharia-compliant hotels in Egypt: Concept and challenges. Adv. Hosp. Tour. Res. (AHTR) 2014, 2, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Wimeina, Y.; Wahyuni, D. Identification of Halal Destination Criteria Fulfillment within Padang Beach Area as Tourism Attraction Icon of the City of Padang. In Proceedings of the International Conference of Applied Science on Engineering, Business, Linguistics and Information Technology (ICo-ASCNITech), Padang, Indonesia, 13–15 October 2017; pp. 299–2532. [Google Scholar]

- Talib, M.; Hamid, A.B.; Zulfakar, M.; Jeeva, A. Halal Logistics PEST Analysis: The Malaysia Perspectives. Asian Soc. Sci. 2014, 10, 119–131. [Google Scholar]

- Talib, M.S.A.; Rubin, L.; Zenghyi, V.K. Qualitative Research on Critical Issues in Halal Logistics. J. Emerg. Econ. Islam. Res. 2013, 1, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R.E.; Harrison, J.S.; Wicks, A.J.; Parmar, B.L.; De Colle, S. Stakeholder Theory—The State of the Art. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2010, 4, 403–445. [Google Scholar]

- Presenza, A.; Cipollina, M. Analysing tourism stakeholders’ networks. Tour. Rev. 2010, 65, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, L.R.; Ritchie, J.R.B. Destination stakeholders: Exploring identity and salience. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 711–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timur, S.; Getz, D. A network perspective on managing stakeholders for sustainable urban tourism. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2008, 20, 445–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuohino, A.; Konu, H. Local stakeholders’ views about destination management: Who are leading tourism development? Tour. Rev. 2014, 69, 202–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franch, M.; Martini, U.; Buffa, F. Roles and opinions of primary and secondary stakeholders within community-type destinations. Tour. Rev. 2010, 65, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komppula, R. The role of different stakeholders in destination development. Tour. Rev. 2016, 71, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laesser, C.; Beritelli, P. St. Gallen consensus on destination management. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2013, 2, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strobl, A.; Peters, M. Entrepreneurial reputation in destination networks. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 40, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kern, F. The Trials and Tribulations of Applied Triangulation: Weighing Different Data Sources. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2018, 12, 166–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekhet, A.K.; Zauszniewski, J.A. Methodological Triangulation: An Approach to Understanding Data. Nurse Res. 2012, 20, 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flick, U. Editorial Introduction. In Doing Interviews—Steinar Kvale; Flick, U., Ed.; The Sage Qualitative Research Kit, Sage Publications: London, UK, 2007; pp. ix–xiii. [Google Scholar]

- Kvale, S. Introduction to interview research. In Doing Interviews—Steinar Kvale; Flick, U., Ed.; The Sage Qualitative Research Kit, Sage Publications: London, UK, 2007; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Kvale, S. Qualitative Inquiry between Scientistic Evidentialism, Ethical Subjectivism and the Free Market. Int. Rev. Qual. Res. 2008, 1, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuirk, P.; O’Neill, P. Using Questionnaires in Qualitative Human Geography. In Qualitative Research Methods in Human Geography; Hay, I., Ed.; Faculty of Social Sciences—Papers; Oxford University Press: Don Mills, ON, Canada, 2016; pp. 246–273. Available online: https://ro.uow.edu.au/sspapers/2518 (accessed on 6 January 2021).

- Ishikawa, T. Japanese university students’ attitudes towards their English: Open-ended email questionnaire study. In ELF: Pedagogical and Interdisciplinary Perspect; Tsantila, N., Mandalios, J., Ilkos, M., Eds.; Deree—The American College of Greece: Athens, Greece, 2016; pp. 87–94. [Google Scholar]

- Murgan, M.G. A Critical Analysis of the Techniques for Data Gathering in Legal Research. J. Soc. Sci. Hum. 2015, 1, 266–274. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, V.; Braun, V. Thematic analysis. J. Posit. Psychol. 2017, 12, 297–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, K.E.; Latin, R.W. Essentials of Research Methods in Health, Physical Education, Exercise Science and Recreation, 3rd ed.; Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdan, R.C.; Biklen, S.K. Qualitative Research for Education, 5th ed.; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lune, H.; Berg, B.L. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences, 9th ed.; Pearson: Harlow, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Terry, G.; Hayfield, N.; Clarke, V.; Braun, V. Thematic Analysis. In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology, 2nd ed.; Willing, C., Stainton-Rogers, W., Eds.; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

| Gender | 13 men, 12 women |

| Age | Between 26 and 71 years old. Average 44 |

| Workplaces | 6 hotels and hostels |

| 3 museums | |

| 5 tourism consulting/PR companies/marketing | |

| 2 governmental authorities | |

| 3 municipal or regional tourism bureaus | |

| 1 destination management company, 1 sale agency, 1 amusement park, 1 tour operator, 1 cruising company | |

| 1 did not answer | |

| Position | 8 managers/section managers |

| 4 owners | |

| 5 CEOs | |

| 2 communicators | |

| 2 receptionists | |

| 1 analyst, 1 international marketing officer, 1 trainee | |

| 1 did not answer | |

| Work experience in tourism industry | Between 1 and 45 years. Average 21 years |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abbasian, S. Good Idea But Not Here! A Pilot Study of Swedish Tourism Stakeholders’ Perceptions of Halal Tourism. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2646. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052646

Abbasian S. Good Idea But Not Here! A Pilot Study of Swedish Tourism Stakeholders’ Perceptions of Halal Tourism. Sustainability. 2021; 13(5):2646. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052646

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbbasian, Saeid. 2021. "Good Idea But Not Here! A Pilot Study of Swedish Tourism Stakeholders’ Perceptions of Halal Tourism" Sustainability 13, no. 5: 2646. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052646

APA StyleAbbasian, S. (2021). Good Idea But Not Here! A Pilot Study of Swedish Tourism Stakeholders’ Perceptions of Halal Tourism. Sustainability, 13(5), 2646. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052646