Abstract

Research on the COVID-19 crisis and its implications on regional resilience is still in its infancy. To understand resilience on its aggregate level it is important to identify (non)resilient actions of individual actors who comprise regions. As the retail sector among others represents an important factor in an urban regions recovery, we focus on the resilience of (textile) retailers within the city of Würzburg in Germany to the COVID-19 pandemic. To address the identified research gap, this paper applies the concept of resilience. Firstly, conducting expert interviews, the individual (textile) retailers’ level and their strategies in coping with the crisis is considered. Secondly, conducting a contextual analysis of the German city of Würzburg, we wish to contribute to the discussion of how the resilience of a region is influenced inter alia by actors. Our study finds three main strategies on the individual level, with retailers: (1) intending to “bounce back” to a pre-crisis state, (2) reorganising existing practices, as well as (3) closing stores and winding up business. As at the time of research, no conclusions regarding long-term impacts and resilience are possible, the results are limited. Nevertheless, detailed analysis of retailers’ strategies contributes to a better understanding of regional resilience.

1. Introduction

While research on COVID-19 has sharply increased during the year 2020, particularly in health science, bibliometric studies show that research in “physical sciences and social sciences and humanities lag behind significantly” [1] (p. 1). While it is argued that most other natural disasters including epidemics (e.g., SARS, Zika, Ebola) have temporal and spatial boundaries, the COVID-19 pandemic is seen to be transboundary and thus particularly challenging in terms of crisis management [2,3]. The virus is highly infectious and spreads quickly in times of increasing interconnectedness in economic, societal and private realms, and can have severe consequences (including death), particularly for elderly people as well as such with pre-existing health issues. However, while the pandemic is a biological or health crisis at first, restrictive governmental measurements threaten (transnational) societal and economic networks, locations and sectors on various scales. Even though the pandemic is global, the impacts are spatially uneven and become visible and tangible at certain locations and on individual levels. Uncertainty about measurements and time spans are particularly challenging on local and regional levels where the crisis is managed and measures are enforced [2]. Consequently, COVID-19 combines a health emergency with an economic crisis, making it a shock that is global and systemic in nature. Even though anticipatory risk management systems (natural and financial disasters) have become more common practice in order to strengthen sustainable development pathways, the latest in the aftermath of the financial crisis 2007/08 [4], they are of little value in the realm of COVID-19 pandemic. Governmental measures undertaken to prevent the virus from spreading included the restriction of people being spatially mobile, of businesses opening their shops as well as of industries producing their goods. This challenges retailers not only as they have to keep paying their dues, but also because they have to sell pre-ordered goods under these difficult and restrictive circumstances.

Research on the COVID-19 crisis and the implications for regional resilience is also still in its early stages [5]. Within urban regions, retail constitutes a major economic contribution and has significant societal and functional importance. As such, retail resilience can be seen as an important component for regional recovery [6] during and after crises. We contribute to existing research by analysing individual retailers’ resilience in times of the crisis initiated by measures responding to the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany beginning March 2020 and interpreting their effect on the resilience processes of the region. The focus on retailers makes sense as in addition to the disruptive changes that challenge their resilience and adaptability in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic, structural changes of recent years prevail, confronting retailers with short- as well as long-term hurdles. With approximately 410,000 small and medium-sized enterprises, around three million employees and an annual turnover of almost 500 billion euros, the retail sector represents the third largest industry in Germany [7]. The current COVID-19 pandemic, declared by the World Health Organization on 30 January 2020, led to two government sanctioned lockdowns in Germany (beginning 17 March as well as 16 December 2020) and elsewhere, whereby over 200,000 brick and mortar stores were not allowed to open their doors for customers [8], consequently, placing an enormous burden on many retailers. Despite the first easing of restrictions for the retail sector on 20 April, social distance rules, restrictions on the number of people and requirements to wear facemask still applied until the second lockdown in mid-December 2020, which was caused by the second wave of infections. Due to a number of long-lasting structural changes occurring in the retail industry, such as, inter alia, internationalisation, market concentration, digitalisation as well as changing consumer behaviours and demands, it has to be assumed that the COVID-19 crisis will contribute to an increase in the number of insolvencies. Retail locations are threatened by low retail vacancy rates and an increasing desolation of inner cities, which can lead to trading down effects [9], having negative impacts on the (commercial) quality of locations. Yet, a crisis affects different actors, including states and regions to varying degrees, as their reactions to the crisis differ considerably. While some emerge stronger, others face setbacks in their development, and yet others seem to be hardly affected [10] (p. 1). To intervene with trading down effects and to envisage sustainable development for future retail locations and urban centres, the dynamics can be described in terms of short-term resilience.

However, a variety of questions needs to be addressed when assessing resilience, as Martin and Sunley [11] (p. 12) amongst others critically inquire, “Resilience of what, to what, by what means, and with what outcome?” As a starting point for the investigation of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on urban systems, we analyse the spatial unit of Würzburg (Bavaria, Germany) city centre and coping strategies of textile retailers. Textile retailers seem to be among the most affected to the restrictions during and after the (first) lockdown(s) and retail is a major function of modern urban systems. Even though urban systems consist of many more social actors and stakeholders, the analysis of how (textile) retailers transform or persist and co-create functions, networks and agents of urban systems contributes to a better understanding of urban/regional resilience dimensions and processes. In consequence, we inquire multiple aspects of resilience on different scales, such as resilience of retailers (micro scale), e.g., [6,12], as well as of urban and regional units (meso scale), e.g., [13,14,15,16].

To achieve this aim, this study addresses the following main research questions: (1) How do individual retailers cope with the challenges of COVID-19?; (2) What kind of strategies do they apply?; as well as (3) How do the individual strategies contribute to the retailer’s resilience and the retail resilience to the regional resilience of the inner city of Würzburg accordingly?

To answer the research questions, this paper adopts a single case study approach based on thirteen in-depth interviews with mainly textile retailers. While resilience approaches in (evolutionary) economic geography largely focus on certain structures and agents on a macro/mesoscale, Bristow and Healy [14] (p. 928) argue that individual and collective actors play a key role in shaping resilience and that a “greater understanding is needed of how [social actors] behave or act in response to shocks and unanticipated events, and what influences their abilities and opportunities in this regard”. However, as pointed out by Strambach and Klement [10], examined elements relevant for resilience are measured empirically, mostly on the aggregate level. Furthermore, they argue that the actual processes and dynamics of the resistance and reorientation remain thereby invisible. Moreover, regarding factors of influence and effects only on the aggregate level, the heterogeneous distribution of the adaptability on the actor level remains hidden [17]. Thus, the micro-level relevant for political intervention can therefore still be regarded as largely unexplored. Our approach enables the collection of individual respectively detailed data, still allowing for statements regarding the second level and interpreting processes of co-creation/co-evolution of individual actors and the region. Consequently, the paper adds value to existing research on regional resilience by applying the concept to a pandemic crisis and by providing deeper insight into wider debates on the performance of retailers in particular.

The paper is organized as follows. Firstly, after discussing the theoretical framework, which is based on the concept of resilience, we are linking the two topics of regional and retail resilience. Secondly, we introduce our methods and materials based on the case- study approach adopted. Essentially, we analyse factors influencing the resilience of German-based (owner-operated) retailers in the Bavarian city of Würzburg via a range of expert interviews. The City of Würzburg was chosen as it represents a medium-sized city with above average retail centrality and as such is predestinated to analyse retail resilience during COVID-19. Our results are presented in section three, which is again organized in four subsections. To evaluate whether retailers and regions are resilient or not, we provide information on selected indicators of the socio-economic context of Würzburg and its surrounding region during the pre-crisis period. In the following two subsections, we reveal how COVID-19 affects retailers and how they cope with these challenges. In the final section of our results, we evaluate how retail resilience influences regional resilience and vice versa. The final section of the paper contains a discussion of the results and concluding remarks including an agenda for future research. The results can be summed up as follows: Among the retailers interviewed, a number of differing strategies as well as similar approaches have been identified, ranging from (1) the intention to bounce back to a pre-crisis state, (2) the establishment of additional sales channels and/or adaption of assortment mix or (3) the decision to close the store and to wind up the business. Concerning the co-construction of retail and regional resilience, our study adds to existing research as it reveals that regional and retail resilience mutually interact, while offering insights into resilience strategies on the micro-scale level.

Theoretical Background

The theoretical framework is based on the concept of resilience. Yet, a number of definitions exist and while the concept’s flexibility and inherent inclusiveness represents both its strength and weakness, there is much confusion on its actual meaning as well as its relation to “other key concepts like sustainability, vulnerability, and adaptation” [18] (pp. 311–312). Broadly speaking, resilience describes “how various types of systems respond to unexpected shocks” [19] (p. 5). Indeed, it has to be noted that the exposure of systems to unexpected shocks, events or structural change can also be explored alongside concepts such as vulnerability or sustainability that overlap in many dimensions [20]. As discussed elsewhere, e.g., [10,14], resilience is applied in various scientific disciplines, such as psychology [21,22], engineering, biological or earth science [23,24], supply chain management [25,26] and strategic management [27]. Thus, conceptualizations of resilience vary according to the reference systems (e.g., individual psychology, socio-ecological system, industry, actor network, spatial unit, etc.), the strategies (e.g., reactive or proactive), or the outcomes that are seen as being resilient (equilibrium or dynamic adaptation processes), e.g., [6,13,28]. Regarding the ability to dynamically adapt to external disturbance and permanently reorganise and co-create its configurations, Weick [29] as well as Lengnick-Hall and Beck [30] take this approach further and argue in the context of management strategies and organizational resilience that resilience reflects the capability to even emerge stronger from crisis/shock. To take advantage and improve during times of crisis or shock is sometimes described as “bouncing forward” [31] (p. 5).

In human geography, resilience is applied in several contexts e.g., in terms of urban, social or community resilience [5,32]. In economic geography, resilience is applied to an economic system “whether that is local, regional, national or supranational” or individual actors “such as firms, households, policy bodies or other actors” [33] (p. 2). Resilience is seen as the ability of an economy to at least retain its functionality for its actors in times of (external) disturbance [10,23,34,35]. Strambach and Klement [10] (p. 265) note that keeping a system’s functionality does not mean that structures and form remain the same. Instead, transformations of structural settings and configuration may occur to retain the system’s functionality. Thus, regional resilience includes both notions of equilibrium and adaptive capacity. Schiappacasse and Müller [36] (p. 57) confirm that in their systematic literature review “the dominating understanding includes resilience as both a state and a process”.

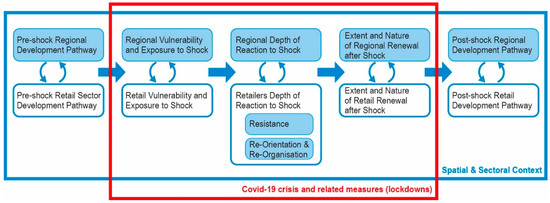

A widely recognized approach to regional resilience in geography focusses on regional economies shaped by certain industries, sectors, firms and institutions and is conceptualized by Martin [17], who identifies four interrelated dimensions that are seen to be necessary to understand the response of economic regions towards external shocks, namely resistance, reorientation, recovery and renewal. More current research on regional (economic) resilience, e.g., [5,11,37,38], develops this approach further and introduces three remaining dimensions, namely resistance, reorganisation/reorientation, recoverability (Figure 1). Resistance represents the persistence of a region or the ability to withstand a shock, which also reflects the vulnerability of a regional economy to crisis and is related to equilibrium notions of resilience. (Structural) reorientation (and reorganisation, as in the case of Evenhuis [38]) entails transformative practices and the extent of undergone changes and their implications for the region. Recovery concerns the speed, extent and nature of recovery that can resume pre-shock pathways as well as functionally or structurally shifted post-shock developmental pathways [10]. As such, recovery can reflect equilibrium and adaptive capacities. To put it in a nutshell, Foster [28] (p. 14) argues that “regional resilience [is] the ability of a region to anticipate, prepare for, respond to, and recover from a disturbance”.

Figure 1.

Regional and Retail Resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic. Source: Adapted from Martin and Sunley 2015 and Martin et al., 2016. Design: Julia Breunig.

The resilience framework strengthens some basic arguments derived from evolutionary economics, such as the advantages of diversity [17], seeing regional economies as path-dependent systems [39], or the potential of novelty and selection in economic systems as they adjust to evolving circumstances [15,40]. Furthermore, Dolega and Celinska-Janowicz [41] argue that future resilience of town centres is crucially dependent upon recognising and acting upon the challenges arising from current trends.

Whereas the significance of regional resilience, usually a mesoscale approach deriving from evolutionary perspectives on economies and regions [16] is still undecided, it is argued “that major shocks may exert a formative influence over how the economic landscape changes over time” [17] (p. 2).

Besides the recognition of useful insights concerning path-dependencies and path-creation of regions for creating resilience and hence sustainable development, the concept of (regional) resilience has not yet been applied without disapproval. Christopherson et al. [42] argue that the inquiry of regional resilience is an old one, generally questioning why some regions manage to overcome economic hardship while others do not. In a special issue on regional resilience in the Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, Pike et al. [43] generally criticize the application of equilibrium approaches. Hassink [39] even rejects the concept of regional resilience overall as it disregards the long-term aspects of regional adaptation. Christopherson et al. [42] (p. 7) similarly object that the competitiveness of a region is so deeply entwined with the growth of the economy that the contribution of resilience regarding the factors of regional sustainability and the relation between environmental and economic development is overlooked. They [42] (p. 6) argue that the concepts of adjustment and adaptation prove “more useful in analysing regional resilience”, yet, arguing that what makes a region stronger could weaken it for other crises to come. Bristow and Healy [14] (p. 928) equally point out that “[a] region may therefore be resilient in certain respects (e.g., in relation to its firms), but not in others (e.g., its labour market)”. Hu and Hassink [44] criticize the general disregard of regions’ adaption to a ‘slow-burn’ crisis in the long-term. Resilience has been criticized as being a comparatively fuzzy concept as it was developed in the realm of ecological systems being applied in social contexts [10,44]. As such, resilience is positively attributed even in social systems, whereby power relations are negated [34] as stability or equilibrium can mean to stabilize power relations and interests [36] (p. 53). Further criticism of the approach is levelled at its neglect of the role of actor-networks beyond the firm [43,44] and the “agency of actors in the system and how they might shape resilience capacities and emergent outcomes” [14] (p. 927).

While we recognize that urban environments in general are “[c]omplex, multi-scalar systems composed of socio-ecological and socio-technical networks that encompass governance, material and energy flows, infrastructure and form, and social-economic dynamics” [13] (p. 45), for our case studies we focus on the role of retailers’ agency in shaping their present/future. In other words, this implies that urban resilience has social, institutional, physical and economical dimensions. We focus on the economic dimension in the realm of textile retail.

Indeed, Müller [45] (p. 5) notes that there are plenty of inherent features that make some cities more resilient than others. Additionally, Christopherson et al. [42] point to manifold factors that influence and shape the resilience of regions. Examples are individual and collective human perception, behaviour and interaction, regional specific networks and varieties of actors, institutions and infrastructures or aspects like political and community governance and the ability to anticipate and plan for the future, but also creative and innovative workforce and a (diversified) commercial base [12,42,45].

Bristow and Healy [14] (p. 333) point out that further research is needed to understand how individual (non)action affects the aggregate resilience of a region or urban system and vice versa, calling for more empirical work in order “to understand these lower-level processes and behaviours and how they vary spatially, as well as how they then relate to and shape the ‘emergence’ of macro‘ structures and performance outcomes”. While Martinelli et al. [6] argue that the retail sector seems to represent an important factor in an urban region’s recovery, we reason that it can contribute to a regions resilience in general (Figure 1). It has been found that it is particularly vulnerable to natural disasters immediately after such events due to its dependence on consumption within times of uncertainty and (expected) economic crisis in which consumption can waiver [6]. Dolega and Celinska-Janowicz [41] (p. 10) as well as Martinelli et al. [6] (p. 1223) write that “the analysis of how small retail entrepreneurs mobilize their capabilities in the face of adverse events is limited in the literature, and the resilience concept has been rarely applied or studied for the retail sector”. In the context of earthquakes, a high ratio of closure among retailers could be identified as immediate response [46,47]. Moreover, it has been observed that the retail sector recovers quickly after natural disasters as it supplies people with daily needed goods and plays a crucial role in social terms [47].

We describe the individual retailer’s reactions to the crisis by applying the concept of resilience as introduced by Martin and Sunley [11] and known in economic geography, thereby focussing on the dimensions resistance and reorganisation/reorientation. As the crisis is still ongoing at the time of writing, the dimensions recovery/renewal or respectively the dimension of recoverability cannot be evaluated yet and are consequently neglected.

In our understanding of resilience, the microscale resilience of individual retailers (among others) influences the mesoscale resilience of the urban centre and vice versa. As argued earlier it is not an ‘either or’ of particular outcomes (e.g., equilibrium vs non-equilibrium) or strategies that lead to retailer or urban resilience, rather we can identify different forms of resilience within one region and among retailers. Indeed, how resilient a region/actor/etc. genuinely is can only be assessed during and after critical events, while at the same time resilience depends highly on individual assets [28] and “outcomes [that] need to be judged in relation to a region’s own ‘norms’” [14] (p. 933).

The paper addresses the paucity of research in the far-reaching role that resilience may play in the German retailing landscape in the midst of the COVID-19 crisis and the associated challenges. Conducting a contextual analysis of the Würzburg city centre, we wish to outline the region’s pre-crisis settings. Moreover, we examine whether observable strategies of individual retailers can contribute to sustainable development and regional resilience.

2. Materials and Methods

The methodology applied in this paper is as follows: Firstly, the individual retailers’ level is considered by conducting thirteen semi-structured expert interviews.

The interview partners were selected on the basis of a snowball sample. Initially, three representatives of retail relevant institutions (municipal representative, trade association, chamber of commerce) were identified as important informants, who in turn were asked at the end of the interviews, respectively, to name important case studies reflecting best and worst case scenarios. As the institutional representatives and the retailers aredifferently exposed to and affected by the crisis, their reflections differ accordingly. While the institutional representatives can be seen as experts overlooking a whole sector in a certain regional setting, the retailers are experts in their own business practices in specific locations, yet, most of them are very well informed about the sectoral and regional dynamics. The choice of our case study is motivated as follows. We have chosen textile retailers located in the city centre of Würzburg as they were and still are heavily affected by the lockdowns and the continuing restrictions imposed by the German government in response to the COVID-19 crisis. The example of Würzburg has been chosen, as it is an affluent medium-sized city with an above-average retail centrality; thus, representing an interesting example: On the one hand, the retail centrality may expose the businesses to the negative effects of fewer consumers. On the other hand, the city’s economically strong pre-COVID-19 circumstances and assets may lend it a higher level of resilience both during and post-COVID-19. The interview partners were the owner/senior executives of the respective retailers (Table 1). While some run clothing shops that specialise in women’s fashion, others operate highly specialized stores in terms of festive clothing. All interviewees point out the high and comprehensive customer service they offer. In order to receive a more balanced observation and further knowledge regarding the wider, regional level, additional retail specialists and consultants were questioned. These include representatives of the city, trade associations and retail related institutions. All interviews took place between October 2020 and January 2021 (via Zoom or personally) and lasted 50 to 140 min. We recorded and transcribed the interviews before their analysis. All interviews were conducted and analysed in the same way. Interview questions asked covered five main topics, namely:

Table 1.

List of Interview partners.

- Effects (e.g., What are the biggest challenges/problems your institution/organization/company has to deal with since the COVID-19 pandemic? Which of these challenges have existed before? Have they changed or intensified?)

- Würzburg city centre and surrounding area (e.g., What are the biggest challenges/problems for the retail trade in Würzburg since the COVID-19 pandemic—also compared to other regions; are there any specifics and if so, which ones and why?)

- Institutional and stakeholder environment (e.g., Do you use state/municipal/regional/private/institutional help or support measures? If so, which ones? If not, why not?)

- Reactions (e.g., If measures were taken: What do you hope to achieve through the implemented measures? Do you already assess the measures as successful? Do you want to keep them also “after” the COVID-19 pandemic? If you do not plan to continue the strategy(s), why not?)

- General assessment (e.g., Should similar crises occur again in the future, do you feel prepared to react appropriately?)

Secondly, in order to allow a conceptual analysis, secondary sources such as retail news report and industrial analytical reports provide contextual narratives related to the actions adopted by the respective retailers.

A limitation of this paper lies in the small number of expert interviews due to the restricted time frame since the start of the first lockdown in Germany in March 2020 is considerably short, long-term effects are not yet fully predictable and data collection could not occur as comprehensively as in studies on established subjects. Moreover, there is a risk that respondents might be subjective in their assessments of their own company’s circumstances as well as procedures and skills, as the COVID-19 crisis poses a heavy burden on most of the retailers, representing an emotional situation. Further, Williams et al. [48] point out the challenge of actor’s time perception, as interviewee’s assessment of which time period is relevant to the crisis, may differ significantly. Still, the explorative character of the study allows the propositions of initial conceptualizations as well as the derivation of numerous implications, which are of great value to further research in this field.

3. Results

3.1. Framing Retail Resilience: (Pre-Crisis) Conditions in Würzburg

With an area of 87.6 sq. km and around 130,000 inhabitants, Würzburg ranks as the fifth largest city in Bavaria and represents an important regional centre [49], revealing its importance among others in the areas of education and science as location for universities (JMU, FHWS, university of music) as well as for research centres such as Fraunhofer Institute. Besides being a cultural and business centre within the region of Mainfranken, Würzburg is the administrative centre where the regional government of Lower Franconia is located. In addition to approximately 35,000 students living and studying in Würzburg, “two-thirds of the employees in Würzburg commute in what reflects the cities transregional integration” (Interview II). Additionally, before the COVID-19 pandemic until the end of 2019, Würzburg had increasing high numbers of day visitors, 13 million, and 900,000 overnight visitors (Interview II).

The structural and functional importance of Würzburg is seen as an aspect that increases its resilience: “So you can see the transregional importance of Würzburg. And these are structures that perhaps also make it easier to cope with such a crisis compared to other locations here in the region” (Interview II). Further socio-economic indicators that mirror a potentially high resilience of Würzburg were low unemployment rates with 2.3% in 2019 [50] and high per capita income of 23,935 Euro in 2018 [51]. Ehrentraut et al. [52] analysed the impacts of the lockdown(s) on regional economies in Germany and found that in the city of Würzburg only 12.7% of employees paying social insurance contributions work in industries affected by the Corona pandemic, while in the German average this number accounts to 22.4%. This number is not surprising as Würzburg’s economy is largely based on services with the universities being the largest employer. However, services are not included in the study of Ehrentraut et al. [52] (p. 3). Yet, on a general level they [52] (p. 3) state that “large parts of the services sector are relatively ‘crisis-proof’ while the manufacturing sector is more severely affected. Public administration as well as education and teaching services (…) can be seen as comparatively stable in the context of demand and activity. Despite homeschooling and the closure of citizens’ offices, central jobs continue to be performed and wages and salaries are paid normally”. However, besides civil servants and marginally employed persons, self-employed persons are not included in the statistical basis of the study conducted by Ehrentraut et al. [52]. Thus, most independent owner-run retailers, who are seen to be critical of urban environments and account for the most affected by the pandemic crisis, are not represented. However, for our case study, trade and retail play a major role as “Würzburg is a trading city, was a trading city, became a trading city again after the Second World War” (Interview VII).

Regarding retail trade, the city of Würzburg benefits from the lack of other large cities within an immediate 100 km vicinity, leading to the fact that the city’s catchment area includes about 860,000 people [53]. In particular, the volume of retail spending, which was 928 million euros (11,282 euros per capita) in 2019 is significantly higher than the German (6836 euros per capita) average [54]. As pointed out by interviewee III: “Würzburg was doing pretty well. We have an incredibly high centrality rating, 160 to 200 depending on whom you ask, we are a magnet for the surrounding area, we are the shopping city in the region, so people come to us”. The city reveals a historically grown retail structure with nearly 70% of its city centre comprising gastronomy, retail, services and accommodation, while 30% represent residential usage, which altogether shows a good mix of uses [55]. In terms of retail, the city centre is characterized by a high density of retailers within walkable distance. “I believe that Würzburg is cleverly positioned in terms of its inner city structure. You have this pedestrian zone, but these 1b locations then branch off in a star shape, or in a star shape from the market square. And I think that is very important. Because for example in Frankfurt, Stuttgart, these long shopping streets, you can’t find the small stores, because they are too far away. And that is not the case in Würzburg. You can easily get to the 1b locations here. Or even to the 1c locations” (Interview V).

Almost one quarter of retail stores can be assigned to textile retailers [55]. Moreover, Würzburg’s city centre is characterised by a large number of independent / owner-operated retailers, including the textile sector with 61% of companies being owner-managed. This can be attributed to the numerous boutiques as well as some larger, owner-operated department stores [55]. “I think owner-operated specialist retailers are extremely important. Especially for the character of a city” (Interview I). Yet, the mix of chains and independent retailers in Würzburg is rather positive, compared to other cities of similar size [55] (Interview III), with “[b]oth [being] extremely important for the urban character and for the retail mix and also for the attractiveness of retail” (Interview I). While chains ensure greater customer frequency in the city centres, the small independent stores “make it cosy” (Interview X).

3.2. Challenging Retailers: COVID-19 Pandemic and Structural Change

Besides the two lockdowns, the acceleration of structural changes could be identified as the biggest challenge for retailers. The perceived hurdles are analysed in the following subsection. The two lockdowns prevented most retailers operating outside the grocery sector, while the textile sector accounts for one of the most affected retail industries [56]. This is also confirmed by our interviewees (e.g., Interview I, Interview III, Interview II, Interview V, Interview VI). One textile retailer provides the following explanation: “If people don’t attend events [such as weddings or birthday parties] and don’t go on vacation, then they don’t buy anything new. People are insecure; many receive short-time work allowance. And fashion is one of the most likely things to save money” (Interview IV). Besides being among the most severely hit actors, textile retailers are of particular importance for urban environments. The amount of stores and store spaces of textile retailers are among the largest within urban centres and shape a huge part of shopping areas, as it is the case for the city of Würzburg [55,57]. Thus, it can be expected that major restructurings in this retail segment not only would affect retailers on the individual level but also influence functional, physical and economic dimensions of urban environments in the long-run. Several interviewees also confirm that a differentiated analysis is needed, as even within the individual sectors, developments and strategies vary strongly: “it’s very important that we really don’t look at retail in general now, but look at how the single sectors have developed” (Interview I). This is due to the fact that “it is very individual how the crisis is dealt with and was dealt with, so that no general statements can be made” (Interview III). Although we agree on the urgent need to assess resilience on an individual basis, we argue in the following sections for several distinguishable categories of retailers’ strategies.

The first lockdown was perceived as a sudden shock, as one interviewee pointed out: “Everything was ruined over night” (Interview X). In addition to the closure of stationary stores, several uncertainties, such as how long the lockdown will last and which retailers are affected, posed additional challenges at the time of interview (Interview I, Interview VIII) as one retailer states: “No one knew what would happen next” (Interview VIII). While both lockdowns represent direct actions in trying to lower in-person-contacts in society, it could be argued that the second lockdown was more foreseeable for retailers than the first one. Indeed, one retailer confirmed that she felt more experienced with her strategies, set up during the first lockdown, and hence more prepared when the second lockdown was announced: “I think as an entrepreneur (…) I just grew a little bit through the first lockdown, I can react faster now. (…) Compared to the first lockdown there, it already took me a few days to find a rhythm and reorient myself” (Interview XI). Similarly, another retailer states regarding the second lockdown: “We see ourselves quite prepared” (Interview V). One interviewee pointed out that they were thinking pragmatically about a possible second lockdown, pushing online sales and hiring a blogger (Interview IX). While the interviewee will maintain her strategy, an additional member of staff for dealing with the increased online volume has been hired (Interview IX). At the time of research, the second lockdown was still ongoing and it could not be evaluated in how far the experiences and strategies developed during the first lockdown were feasible/sustainable after the second phase of lockdown. However, it can be argued that while the first lockdown was experienced as an unforeseeable shock, the second lockdown turned out to be the real crisis starting one week before Christmas, which usually represents an important time for retail-generated turnover. This was also stated by one retailer: “Even before Christmas, we have to close our stores. (…) Because most customers usually go shopping after Christmas, cashing in their vouchers or spending the money they received for Christmas. These vouchers will now basically turn into online vouchers for Zalando and Co, I assume.” (Interview X). The interview statements on the perception of the two lockdowns show already that different approaches were implemented. While one group of retailers can be identified who proactively reacted to the first lockdown and got prepared for the possibility of a second lockdown, or more generally to changing conditions in retailing, a second group did not undertake large restructurings and waited for the first lockdown to end and go on with business as usual/prior the lockdown. In terms of resilience, these approaches reflect either resistance to the crisis hoping to bounce back or reorientation strategies.

Yet, the interviews also demonstrate that while the store closure represents a major disruption, the question of resilience to what cannot easily be answered, as a number of structural challenges existed prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, e.g., [31] (p. 1). This is also confirmed by our interviewees: “I know that some companies consider not to continue. But this is not completely to blame on Corona, but also other reasons (…) I think structural change will certainly bring forward some things that might have come anyway” (Interview I). As interviewee III points out: “The changes would have happened even without Corona, they are just accelerated now. (…) Of course, people like to blame Corona because they want to legitimize their own failures or inaction. (…) In the past, retailers didn’t see these structural problems and didn’t see any need for action, but now they’re simply coming at them in full force” (Interview III). Structural change in retail can be conceptualized as slow shock and is characterized by digitization, changing consumer behaviour and demand as well as consolidation processes. Moreover, for apparel retail particular challenges include the rising number of seasons and discounts established by chain stores and fast fashion retailers (Interview VIII). One interviewee takes up the aspect of structural change as follows: “The retail sector has of course been forced to rethink. And they [retailers] have also noticed that the business model they have been using for perhaps 20 years is no longer the right one, or perhaps needs to be adapted a bit” (Interview III). Interview statements confirm that COVID-19 can be regarded as accelerant of a variety of structural changes.

3.3. Coping with Challenges: The Resilient Entrepreneur

On a general level, all interviewed retailers adopted mandatory hygiene and safety concepts, cancelled orders if possible and slightly adjusted their assortments. The majority of interviewed retailers offered price reductions once they were able to reopen their stores after the first lockdown in order to attract customers as well as to clear out their storage spaces. However, adjusting orders and assortments in the textile sector is usually not easy as these take place almost one year ahead. Moreover, all retailers took advantage of state aid, in particular short-time working allowances for their staff. A minority took out new loans or arranged rent waivers or deferrals. The biggest difference regarding retailers’ coping strategies could be observed in terms of e–commerce activities. Consequently, one of our main focus points is on online strategies in the following sections. Furthermore, the retailers personality turned out to play a major role regarding the resilience strategies.

Importantly, interviewees reveal that the entrepreneurs themselves seem to be an important source of resilience. This is also confirmed by authors conceptualizing resilience along organizational or community aspects. Indeed, Bristow and Healy [15] (p. 929) as well as Magis [58] (p. 411) see people as “active agents” in resilience who can develop and acquire critical sets of capacity. These processes require awareness of internal and external challenges for the business. One interviewee argues: “I think that many people have become aware of the vulnerable points within their business model as a result of Corona due to this external pressure (…) Those who have now diversified have had positive experiences and will continue to do so (…) those who have now fallen into resignation will have problems” (Interview II). While we generally agree with this argument, we have to point out the important distinction between resignation and non-active measurements that lie in a certain degree of awareness, consideration and conscious decision making for (non-)action. Firstly, we distinguish between two basic categories of retailers, namely proactive and reactive, e.g., [12,28]. While the ability to completely resist disturbances and being able to resume practicing business as usual (equilibrium) after an external shock certainly is one form of resilience, an actor is also resilient if able to dynamically adapt to changing external configurations (adaptive capacity) [59]. In the case of a large specialized family-run retailer, it is stated: “We have cut back our reorders, we have changed our opening hours, and we have also put employees on short-time working. So we have already done a number of things, including some on the cost side, in order to simply get through the crisis in good shape and we will ramp it up again when a certain normality returns” (Interview IV). Yet, regarding new approaches or strategies, they have “not done anything concrete” (Interview IV). Upon being asked whether he would change that approach in hindsight, he argues: “Why should that be? (…) Why should I change something that was highly profitable until six months ago, why should I change something brilliant?” (Interview IV). In addition, he states that “Of course we are suffering from Corona now, but I am convinced that when Corona returns to normal, or disappears, we will be back on track again” (Interview IV). Consequently, we argue that this textile retailer interprets his resilience as a prior-COVID-19 process, operating the business sustainably and building up enough security to survive the pandemic situation without adapting (or being able to adapt) his strategies (with the dimension of resistance prevailing) during the actual crisis.

Being proactive requires knowledge about the structural challenges and opportunities as well as the personal capacity to take risks in decision-making and to be creative and innovative [60]. According to Bristow and Healy [14] (p. 929) “Each agent in a complex system is continually searching for new ways of adapting to the environment. Thus, knowledge about the environment and how it is changing is the key to self-organization and the ability of agents to understand how and in what ways they need to adapt in order to survive”. During crisis, pressure is high and new or creative approaches might be necessary to deal with the unknown situation: “It’s actually different when they say you have to close the store the day after tomorrow and no one is allowed in and then when you’re here on Wednesday and the doors are closed and then suddenly you come up with ideas that you hadn’t thought of three days before” (Interview VII). Besides information, knowledge, awareness, self-organization, etc. there are less predictable aspects that seem to be important for resilience: “I think sometimes [decisions] need a bit of luck, but also someone who possessed the courage” (Interview I), which leads us to the personality of retailers. It can be argued that psychological aspects like personality and positive attitudes help to cope with emerging challenges and create resilience in the business [61]. Quotes from two proactive retailers seemingly coping successfully with the challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic support this argument: “I certainly do not look at anything negative, but only at inspiring things” (Interview V). Another retailer stated “I think you are the architect of your own luck and you have to step on the gas now” (Interview IX). While retailers’ decisions play a critical part, it is also the timescales in which they think, decide and act that are essential to adequately reply to shocks or crisis [48]. Indeed the interviews reveal that for successful crisis management it was crucial how long the shock for the individual retailers lasted for: “(…) we immediately took care of it and did it. Of course, it was a shock at first (…) Yet, then we immediately said we had to do something different. (…) So we didn’t stand still, but immediately went full throttle forward”. (Interview IX). This is also confirmed by the following statement “I also believe that we quickly got out of our state of shock and very quickly decided together as a team, adjusted to the new situation and then looked at what we could do”. (Interview VII). Pantanoa et al. [62] for instance note that retailers who were not quick to adapt and factor COVID-19 into their operations are currently facing an existential crisis, without bolstering this assumption with empirical data. While immediate action is important, the nature and the scope of the strategies are crucial too.

While some retailers attempted to reduce cost by decreasing opening hours and shortening staff, others reacted differently: “Our store was open and the whole team was there to simply say, ‘we are there for the customers’. We give them a sales experience; if they don’t spend money on vacation, they spend it with us” (Interview IX). Some retailers tried several strategies, continuously adapting their approach: “We tried to sell during this first lockdown phase via telephone sales and e-mail. That is extraordinarily difficult and six weeks via telephone didn’t even cover a daily income” (Interview VII). This particular retailer was re-evaluating their strategy on a daily basis. As pointed out by one interviewee, many of the measurements were a result of actionism, “where you had to do something that is not necessarily sustainable” (Interview III).

As argued earlier, diversification can positively contribute to resilience. In the case of one retailer, it is the broad assortment mix, which compensates the loss generated in the textile division (Interview VII). In retail, the diversification of sales channels represents another strategy and can be seen as upgrading/innovation. Archibugi [63] argues that crises enable the creation and the enhancement of innovations as well as their spread due to changing socio-political contexts. Concerning the COVID-19 pandemic, this certainly holds true for the accelerated increase in online retail. According to Dannenberg et al. [64] the severe governmental restrictions regarding society and economy led to a sharp increase in digitalisation, offering the possibility to contribute tremendously to the required reduction in face-to-face contact. Interestingly, retailers reporting the establishment of online retail have had this idea before: “So we have finally made this online store, which has already been in the pipeline for two years” (Interview V). In addition: “We suddenly got the online-store up and running within four weeks” (Interview VII). Others were already operating an online store, yet did not push online retail as strongly as they do now (Interview IX). In these cases e-commerce is used to complement the existing offline store, helping not only to generate turnover, but broadening the geographical scope of their customers: “We also thought at the beginning when we launched the online store that now everyone we know would order online. However, it is exactly the opposite. It’s almost exclusively new customers and that’s from all over Germany” (Interview V). The quick focus on online sales did not only help in creating turnover, but helped clearing the current inventory (Interview IX).

Other retailers decided against the establishment of e-commerce for several reasons, such as the complexity and lack of expertise and time (e.g., Interview VIII). Answering why they would not engage in e-commerce: “We are relatively clear in our demarcation in our strategy and clear in our corporate philosophy. For us, we have determined in our corporate philosophy, which we have also worked out over a longer period of time, that e-commerce is not a solution for us” (Interview IV). Yet, in several other cases, highly active approaches have been adopted, such as the implementation of digital applications, including the engagement in e-commerce. While it is clear that communication and exchange, e.g., [14,58], are critical to acquire information and knowledge to (re)shape behaviour, it becomes increasingly important to gain knowledge about how to operate digital communication for acquiring and spreading information to reach customers or a desired group of people. Establishing online sales channels or shifting the focus to online sales and marketing can be regarded as a successful reorientation during the COVID-19 crisis, consequently strengthening resilience. While some recognize this need or opportunity, as in the case of Interview XI, who states: “Of course during this lockdown it’s our only way to reach people quickly and bring them with us. It has always been important, but even more so now”, others were not able to successfully implement an online strategy due to several reasons, such as the unsuitability of products, the lack of knowledge, time and money as well as the non-existent possibility of marketing extra services that were usually seen as a competitive advantage, therewith preventing resilience. While Martin [17] (p. 15) argues that “adaptation is arguably a key source of economic resilience”, we find evidence that the adaption might also lead to emerging stronger from crisis/shock (Interview XI, Interview V, Interview IX), confirming the findings, such as of Weick [29] as well as Lengnick-Hall and Beck [30]. This concurs with Martinelli et al.’s [6] (p. 1224) line of argumentation, namely, that resilience represents “the ability to turn challenges into opportunities, and thereby improv[ing] performance”. One interviewee clearly confirms this anticipation: “Corona has really, as bad as it sounds, but without the pressure, we would not have gone through all these measures with such harshness and sometimes brutality. As the saying goes, necessity is the mother of invention, and necessity sometimes gives you the argument” (Interview VII).

3.4. Re-Contextualizing Retail Resilience in Würzburg

Besides the impact of individuality and retailers’ personality, the specific impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on retail structures also depends on location-specific factors, both internal and external to the retail sector. These might include aspects such as infection rates, existing mix of use and management mix (chain store operator vs. owner), ownership structures (leaseholders or owners of store premises), creativity and willingness to innovate on part of the retailers, municipal management style, financial situation of the municipality, purchasing power, unemployment rates or insolvencies. For Würzburg, one aspect is the traditionally strong focus on retail trade, which is also reflected in a high number of long-established retailers in certain locations: “They are located very strongly in the 1A and 1B locations and are dependent on foot traffic, and they have of course experienced this lockdown situation very negatively” (Interview II). While store location and customer structure may impact lockdown consequences, business models and their adaptations differ and these differences seem to be crucial: “I would now use the metaphor of a generation change to a certain extent, because we have a younger generation that is much more proactive and has a greater affinity for digital business and adapted its business model with corresponding digital strategies years ago. In terms of product ranges, procurement, and so on, they were much less afflicted than these traditionalists” (Interview II).

Not only in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and the lockdowns do digitization and e-commerce represent essential factors. Particularly for the city of Würzburg, a marketing advisor commented by email that there is almost no information on retail digitization processes in the region at all and wonders: “Why are retailers in Würzburg so reluctant to ‘digitize’?” [65]. One interviewee considers the following: “I think it shows a little bit this difference between old established and younger companies and stores. Because younger stores react on the market easier and faster. To say ok we’re going to go on Instagram and bash everything on it. (…) And as a small store I can more easily say ok, we’ll leave this now and go full throttle here and I think in these larger companies and businesses that’s sometimes harder to do” (Interview XI).

As for the resistance regarding the structural change and digitization in particular prior to COVID-19, several arguments were brought forward: “In many places we have fallen on deaf ears, because the need was ultimately not given, the sales were ok, you were satisfied with what you had” (Interview II). While the application of adaption processes sounds like a simple undertaking from the viewpoint of this interviewee, for some retailers this stands in sharp conflict to their personal vision of being a stationary retailer: “The merchandise is one thing, but the people who stand there and sell it with their heart and soul are the most important thing. (…) And you can’t do that online either” (Interview IX). Even if there is/was a strong desire to operate a stationary retail store, retailers who did not overlook current trends in demand, behaviour and digitization—even before the recent pandemic—turned out to be stronger (in terms of sales) during the lockdowns. Consequently, we argue that resilience is also based on awareness of and facing these structural challenges prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Generally, the interviewees were positive about the long-term retail developments in Würzburg as a transregional centre (e.g., Interview I, II, III). One interviewee states: “I think that will remain so. Sure, maybe the one or the other buys more online, but I still believe that people would like to go to Würzburg, that’s just a different experience to go into the stores and stroll through the streets and alleys” (Interview XI).

Martin [17] and Dawley et al. [66] argue that a more diverse economic structure contributes to regional resilience. Applying this line of argumentation to the case of Würzburg, it can be reasoned that the pre-crisis mix of use, assortments and ownership structures positively adds to resilience. Further, the high level of employees in service sectors such as administration, teaching and education as well as the high-average per-capita income allow the assumption of a low vulnerability of Würzburg and the region. However, as Würzburg city centre is characterized by high retail centrality among other indicators, it could also be particularly vulnerable to the threats confronting the retail industry. Yet, the development of centrality post-lockdown is unknown, as future consumer preferences (for example shopping regionally or online) as well as long-term impacts on sustainability of retail strategies are not fully predictable at this moment. Nevertheless, we argue that due to individual retailers’ successfully adopted strategies, retail resilience might contribute to regional resilience and vice versa.

Regarding the regional resilience, we argue that the positive framework conditions regarding Würzburg contribute positively to retailers’ medium-term resilience. Once they have overcome the lockdown, opening up their stationary shops, it can be assumed that the economic impact will be less severe due to factors mentioned above. Many interviewees reflected this optimistic outlook upon Würzburg: “After the first lockdown, some of the regular customers specifically supported their favorite stores. One customer said that she now spends the money she saved in the last few weeks specifically in the stores she wanted to support. (…) That really lifted our spirits. (…) I wouldn’t mind if it will be like that again after the current lockdown. (…) I bet a lot of people will come back now” (Interview XIII).

Generally, while the majority of interviewees seem optimistic, several point out that changes of the inner city will occur, such as, inter alia, shop closures, and that COVID-19 triggered selection processes. Hence, all of the interviewees agree to the assumption that Würzburg will retain its high transregional integration and centrality.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed a major shock on regions and their actors. Especially the two lockdowns imposed by the German government as a response to the pandemic heavily affected the retail sector.

We found that the two lockdowns were perceived as different in character. While the retailers interviewed regarded the first lockdown as a sudden shock, the second one was potentially more foreseeable, yet accelerated the challenges due to extending the duration of crisis. However, many developments occurring during the pandemic could be observed prior to the COVID-19 crisis, such as changing consumer preferences (e.g., ecommerce). We observed that retailers, who already started adapting to structural changes occurring prior to the pandemic, were able to respond more successfully to the challenges posed by the COVID-19 crisis. Furthermore, we argue that the duration of the resistance phase represents a crucial factor as to the overall resilience of the retailer. In the case of the interviewed textile retailers, those who quickly moved beyond the stage of resistance, but rather actively adapting their strategies, seem more successful. Yet, this does not imply that the strategies adopted during this time necessarily make them more resilient for future developments to come. However, in our interviews we identified three types of entrepreneurs (Table 2), such as the ones (1) intending to “bounce back” to a pre-crisis state, (2) reorganising existing practices, and (3) exiting business. Generally, the resilient entrepreneur is characterized by a high level of awareness and conscious decision-making. From the perspective of retail, the first two strategies represent a resilient entrepreneur, while the third strategy could be described as non-resilient. Yet, looking from a personal retailer’s point of view, the exiting strategy might also epitomize a rather resilient option, due to personal preferences or future plans. This highlights the fact that resilience is multi-layered in nature, mutually interacting and consisting of fluid dynamics. As such, resilience in one context does not necessarily mean resilience in another. However, from a broader perspective, two main groups of resilient retailers can be distinguished: The ones that intend to “bounce back” to a former stage, holding on to their previous/prior-COVID-19 strategy and the ones that use this kind of new window of opportunity for fundamental changes such as enhanced online strategy that may be favorable to sustainable development. This confirms the assumption that the crisis leads to selection processes, “separating the wheat from the chaff”, as articulated by one interviewee (Interview IX). The paper concludes that the crisis was particularly challenging for retailers with a strong focus on individual services, such as individual customer advisory, tailoring or even manufacturing of individual products. While all store-based retailers emphasized their philosophy to provide customers with extraordinary advice and service, those who started establishing online sales channels before the pandemic were quicker to expand their online sales to a level that they at least could survive. Rather long-established retailers seem less resilient due to two factors: Firstly, their location is often situated in the inner city centre, making them more dependent on foot traffic and less reachable in times of COVID-19. Secondly, their business routines being highly habitualized and as such often less flexible. Additionally, we found that is more complicated to adapt if the customer structure is characterized by a lower affinity for the Internet and may generally be older.

Table 2.

Summary of main results: Types of retailers’ resilience.

In the case of Würzburg, it can be assumed, that the strong regional assets helped retailers to be resilient. This, in turn, leads to the argument that retail resilience, resulting from individual retailers’ successfully adopted strategies, might contribute to regional resilience and vice versa. On a more general level, regional resilience is an inherently aggregate perspective. As such there is no ‘one’ type of actor contributing to high regional resilience. However, considering regional resilience in terms of processes that retain inner cities as trans-regionally integrated and central multipurpose/shopping locations, all of the three identified retailer types are contributing. Regional resilience is not increasing if all actors reacted the same.

While a detailed analysis of retailers’ strategies contributes to a better understanding of regional resilience, our findings nevertheless remain limited, as at the time of research, conclusions regarding the resilience to the second lockdown are not possible. Further limitations are grounded in the relatively small sample size. Moreover, the analysis of the region’s resilience remains superficial, as at the time of research conducted, the lockdowns were still in place. Yet, the Delphi method, which is a structured communication technique, originally developed as a systematic, interactive forecasting method, could be pointed out as an alternative when interviewing experts. Generally, research on resilience in pandemic crisis is still in its infancy. Our interviews opened up a multitude of further research agendas, such as the question of how to actually determine and measure retail resilience. Future research on COVID-19 should adopt concepts such as sustainability and vulnerability to analyse the exposure of systems to the pandemic [67]. Further research should address the role of social ties, such as loyalties of customers, staff and families or the embeddedness in multi-scalar and even digital networks. It can be assumed that social ties and interactions support resilience processes of retailers, particularly small entrepreneurs, and urban regions alike. Moreover, the interaction between economic and institutional actors as well as actors from civil society plays an essential role for regional resilience. Now, the question remains open as to whether there are certain actors or actor groups that are of particular importance for regional resilience. For a better understanding of spatially uneven developments, further regional case studies are needed. Given the fact that the crisis is ongoing, future research needs to address long-term effects.

Author Contributions

Both authors contributed equally to the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This publication was supported by the Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Würzburg.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from and anonymity was assured to all interview partners.

Data Availability Statement

The data basis consists of qualitative interviews. Anonymity has been assured to all interview partners.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aristovnik, A.; Ravšelj, D.; Umek, L. A Bibliometric Analysis of COVID-19 across Science and Social Science Research Landscape. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryce, C.; Ring, P.; Ashby, S.; Wardman, J.K. Resilience in the face of uncertainty: Early lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Risk Res. 2020, 23, 880–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzigbede, K.D.; Gehl, S.B.; Willoughby, K. Disaster resiliency of US local governments: Insights to strengthen local response and recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Adm. Rev. 2020, 80, 634–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmi, P.; Morrone, D.; Miglietta, P.P.; Giulio, F. How Did Organizational Resilience Work before and after the Financial Crisis? An Empirical Study. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2018, 13, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.; Hassink, R.; Tan, J.; Huang, D. Regional Resilience in Times of a Pandemic Crisis: The Case of COVID-19 in China. Tijdschr. Voor Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2020, 111, 497–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinelli, E.; Tagliazucchi, G.; Marchi, G. The resilient retail entrepreneur: Dynamic capabilities for facing natural disasters. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2018, 24, 1222–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EHI. Handelsdaten—Einzelhandel in Deutschland; EHI, 2020; Available online: https://www.handelsdaten.de/branchen/deutschsprachiger-einzelhandel (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- HDE German Trade Association. Herbstpressekonferenz, Handelsverband Deutschland (HDE) Berlin. 22 September 2020. Available online: https://einzelhandel.de/images/presse/Pressekonferenz/2020/HerbstPK/Charts-Herbst-PK-2020.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- Stepper, M.; Kurth, D. Transformation strategies for inner-city retail locations in the face of E-commerce. Urban Des. Plan. 2020, 173, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strambach, S.; Klement, B. Resilienz aus wirtschaftsgeographsicher Perspektive: Impulse eines “neuen” Konzepts. In Multidisziplinäre Perspektiven auf Resilienzforschung, Studien zur Resilienzforschung; Wink, R., Ed.; Springer Fachmedien: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.; Sunley, P. On the Notion of Regional Resilience: Conceptualisation and Explanation. J. Econ. Geogr. 2015, 15, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkip, F.; Kızılgün, Ö.; Akinci, G.M. Retailers’ resilience strategies and their impacts on urban spaces in Turkey. Cities 2014, 36, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerow, S.; Newell, J.P.; Stults, M. Defining urban resilience: A review. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 14, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bristow, G.; Healy, A. Regional Resilience: An Agency Perspective. Reg. Stud. 2013, 48, 835–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmie, J.; Martin, R.L. The economic resilience of regions: Towards an evolutionary approach. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2010, 3, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschma, R.; Martin, R. Editorial: Constructing an evolutionary economic geography. J. Econ. Geogr. 2007, 7, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R. Regional economic resilience, hysteresis and recessionary shocks. J. Econ. Geogr. 2012, 12, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerow, S.; Newell, J.P. Urban resilience for whom, what, when, where, and why? Urban Geogr. 2016, 40, 309–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, A.D.; Dolega, L.; Riddlesdena, D.; Longley, P.A. Measuring the spatial vulnerability of retail centres to online consumption through a framework of e-resilience. Geoforum 2016, 6, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatto, A.; Busato, F. Energy vulnerability around the world: The global energy vulnerability index (GEVI). J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 253, 118691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, G.E. The metatheory of resilience and resiliency. J. Clin. Psychol. 2002, 58, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powley, E.H. Reclaiming resilience and safety: Resilience activation in the critical period of crisis. Hum. Relat. 2009, 62, 1289–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, B.; Holling, C.S.; Carpenter, S.; Kinzig, A. Resilience, adaptability and transformability in social-ecological systems. Ecol. Soc. 2004, 9, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patriarca, R.; Bergström, J.; Di Gravio, G.; Constantino, F. Resilience engineering: Current status of the research and future challenges. Saf. Sci. 2018, 102, 79–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheffi, Y. The Resilient Enterprise. Overcoming Vulnerability for Competitive Advantage; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ponomarov, S.Y.; Holcomb, M.C. Understanding the concept of supply chain resilience. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2009, 20, 124–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantur, D.; İşeri-Say, A. Organizational resilience: A conceptual integrative framework. J. Manag. Organ. 2012, 18, 762–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, K.A. A Case Study Approach to Understanding Regional Resilience. UC Berkley IURD Working Paper Series. 2007. Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8tt02163 (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- Weick, K.E. The collapse of sense making in organizations: The Mann Gulch disaster. Adm. Sci. Q. 1993, 38, 628–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lengnick-Hall, C.A.; Beck, T.E. Adaptive fit versus robust transformation: How organizations respond to environmental change. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 738–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hynes, W.; Trump, B.; Love, P.; Linkov, I. Bouncing forward: A Resilience Approach to Sealing with COVID-19 and Future Shocks. Environment Systems and Decisions. Environ. Syst. Decis. 2020, 40, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, G.A. “Constructive tensions” in resilience research: Critical reflections from a human geography perspective. Geogr. J. 2018, 184, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bristow, G.; Healy, A. Introduction to the Handbook on Regional Economic Resilience. In Handbook on Regional Economic Resilience; Bristow, G., Healy, A., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2020; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Davoudi, S. Resilience, a bridging concept or a dead end? Plan. Theory Pract. 2012, 13, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, R. From knowledge based economy … to knowledge based economy? Reflections on changes in the economy and development policies in the North East of England. Reg. Stud. 2011, 45, 997–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiappacasse, P.; Müller, B. One fits all? Resilience as a Multipurpose Concept in Regional and Environmental Development. Raumforsch. Raumordn. Spat. Res. Plan. 2018, 76, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.; Sunley, P.; Gardiner, B.; Typer, P. How Regions React to Recessions: Resilience and the Role of Economic Structure. Reg. Stud. 2016, 4, 561–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evenhuis, E. New directions in researching regional economic resilience and adaptation. Geogr. Compass 2017, 11, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassink, R. Regional resilience: A promising concept to explain differences in regional economic adaptability? Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2010, 3, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenken, K.; Boschma, R. A theoretical framework for Evolutionary Economic Geography: Industrial dynamics and urban growth as a branching process. J. Econ. Geogr. 2007, 7, 635–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolega, L.; Celińska-Janowicz, D. Retail resilience: A theoretical framework for understanding town centre dynamics. Studia Reg. I Lokalne 2015, 2, 8–31. [Google Scholar]

- Christopherson, S.; Michie, J.; Tyler, P. Regional resilience: Theoretical and empirical perspectives. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2020, 3, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, A.; Dawley, S.; Tomaney, J. Resilience, Adaptation and Adaptability. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2010, 3, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Hassink, R. Adaptation, adaptability and regional economic resilience: A conceptual framework. In Handbook on Regional Resilience; Bristow, G., Healy, A., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2019; pp. 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, B. Urban and Regional Resilience—A New Catchword or a Consistent Concept for Research and Practice? In Urban Regional Resilience. How Do Cities and Regions Deal with Change? Müller, B., Ed.; German Annual of Spatial Research and Policy: Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Wasileski, G.; Rodríguez, H.; Díaz, W. Business closure and relocation: A comparative analysis of the loma prieta earthquake and Hurricane Andrew. Disasters 2011, 35, 102–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearson, M.; Lawrence, K.; Hickman, T. Retail recovery from natural disasters: New Orleans versus eight other United States disaster sites. Int. Rev. Retail Distrib. Consum. Res. 2011, 21, 415–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T.A.; Gruber, D.A.; Sutcliffe, K.M.; Shepherd, D.A.; Zhao, E.Y. Organizational Response to Adversity: Fusing Crisis Management and Resilience Research Streams. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2017, 11, 733–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LEP. Bavaria, Bayerische Staatsregierung: Landesentwicklungsprogramm Bayern; LEP: München, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Statistikatlas Würzburg Statistics of the City of Würzburg. 2019. Available online: https://statistik.wuerzburg.de/ (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- Lozina, K. Würzburger verdienen in der Region am meisten. Main Post. 5 January 2018. Available online: https://www.mainpost.de/regional/wuerzburg/wuerzburger-verdienen-in-der-region-am-meisten-art-9856486 (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- Ehrentraut, O.; Koch, T.; Wankmüll, B. Auswirkungen des Lockdown auf die Regionale Wirtschaft; Prognos, 2020. Available online: https://www.prognos.com/Corona-Regionale-Wirtschaft (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- Comfort Holding GmbH. City Navigator Würzburg; Comfort Holding GmbH: Düsseldorf, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- IHK Würzburg-Schweinfurt. Kennzahlen für den Einzelhandel im IHK-Bezirk. 2020. Available online: https://www.wuerzburg.ihk.de/kaufkraft.html (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- Puff, C. Konzeption Eines Monitoringsystems für den Innerstädtischen Einzelhandel Würzburgs. Master’s Thesis, Julius-Maximilians-University, Würzburg, Germany, 9 November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- HDE. Konsummonitor Corona; HDE, 2020; Available online: https://einzelhandel.de/component/attachments/download/10449 (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- Göbel, M. Einkaufen in der Stadt: Wie Steht der Würzburger Einzelhandel da? Mainpost, 20 June 2020. Available online: https://www.mainpost.de/regional/wuerzburg/einkaufen-in-der-stadt-wie-steht-der-wuerzburger-einzelhandel-da-art-10459943 (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- Magis, K. Community Resilience: An Indicator of Social Sustainability. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2010, 23, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žítek, V.; Klímová, V. Regional resilience redefinition: Postpandemic challenge. Sci. Pap. Univ. Pardubic. Ser. D Fac. Econ. Adm. 2020, 28, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, P.; Parrilli, M.D.; Curbelo, J.L. Innovation, Global Change and Territorial Resilience. In New Horizons in Regional Science; Edward Elger Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Yates, T.M.; Masten, A.S. Fostering the Future: Resilience Theory and the Practice of Positive Psychology. In Positive Psychology in Practice; Linley, P.A., Joseph, S., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004; pp. 521–539. [Google Scholar]

- Pantanoa, E.; Pizzi, G.; Scarpi, D.; Dennis, C. Competing during a pandemic? Retailers’ ups and downs during the COVID-19 outbreak. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 11, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archibugi, D. Blade Runner Economics: Will Innovation lead the Economic Recovery? Res. Policy 2017, 46, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dannenberg, P.; Fuchs, M.; Riedler, T.; Wiedemann, C. Digital Transition by COVID-19 Pandemic? The German Food Online Retail. Special Issue: The Geography of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Tijdschr. Voor Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2020, 111, 543–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anonymous. Personal E-Mail Correspondence. December 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dawley, D.; Houghton, J.D.; Bucklew, N.S. Perceived Organizational Support and Turnover Intention: The Mediating Effects of Personal Sacrifice and Job Fit. J. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 150, 238–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatto, A.; Drago, C. A taxonomy of energy resilience. Energy Policy 2020, 136, 111007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).