Baroque Origins of the Greenery of Urban Interiors in Lower Silesia and the Border Areas of the Former Neumark and Lusatia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods. State of the Art and Sources

3. Results

3.1. Avenues and Tree Espaliers—The Beginnings of Urban Green Space in European Municipalities

3.2. Greenery of Urban Ducal Residences in Lower Silesia

3.3. Tree Espaliers in Municipalities and Their Periphery

3.4. Avenues in Squares and Streets of Lower Silesian-Lusatian Border Municipalities

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Details and Data Supplemental to the Main Text

Source of Figures

References

- Lawrence, H.W. City Trees: A Historical Geography from the Renaissance through the Nineteenth Century; University of Virginia Press: Charlottesville, VA, USA; London, UK, 2006; ISBN 978-0813928005. [Google Scholar]

- Bronisch, P. Geschichte von Neusalz an der Oder; Siltz: Neusalz, German, 1893. [Google Scholar]

- Herda, M. Dyhernfurth; Schlesische Vorzeitung: Wohlau, Germany, 1913. [Google Scholar]

- Kaszuba, E.; Ziątkowski, L. Historia Brzegu Dolnego; Korab: Brzeg Dolny/Wrocław, Poland, 1998; ISBN 83-910321-0-8. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski, S. Kompleks urbanistyczny Żagania jako element dziedzictwa kulturowego. In Dziedzictwo Artystyczne Żagania; Czechowicz, B., Konopnicka, M., Eds.; Oficyna Wydaw. ATUT- Wrocławskie Wydaw; Oświatowe: Wrocław/Zielona Góra/Żagań, Poland, 2006; pp. 17–25. ISBN 8374320435. [Google Scholar]

- Andrzejewski, T.; Gącarzewicz, M.; Sobkowicz, R. Dzieje Nowej Soli. Wybór Źródeł i Materiałów; Muzeum Miejskie w Nowej Soli: Nowa Sól, Poland, 2006; ISBN 83-919139. [Google Scholar]

- Jagiełło, M.; Brzezowski, W.; Wowrzeczka, B. Gardens and parks in the settlments of the unity of the Brethren in Lusatia, Hesse and Silesia in the XVIII century (Herrnhut, Herrnhaag, Niesky, Nowa Sól, Godnów, Piława Górna). Czas. Tech. Archit. 2016, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzezowski, W.; Jagiełło, M. Ogrody na Śląsku. Barok; Oficyna Wydawnicza Politechniki Wrocławskiej: Wrocław, Poland, 2017; Volume 2, ISBN 9788374939522. [Google Scholar]

- Szymańska-Dereń, M. Trzebiechów. In Zamki, Dwory i Pałace Województwa Lubuskiego, 2nd ed.; Bielinis-Kopeć, B., Ed.; Wojewódzki Urząd Ochrony Zabytków: Zielona Góra, Poland, 2008; pp. 417–419. ISBN 978-83-924669-3-2. [Google Scholar]

- Wernher, F.B. Topographia Oder Prodromus Delineati Silesiae Ducatus; Manuscript; Biblioteka Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego (BUWr) Oddział Rękopisów, Biblioteka Cyfrowa Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego: Wrocław, Poland, 1750–1800; Volume 1, Available online: Oai:bibliotekacyfrowa.pl:14302 (accessed on 27 October 2020).

- Wernher, F.B. Topographia Oder Prodromus Delineati Principatus Lignicensis Bregensis, et Wolaviensis [...]; Manuscript; BUWr Oddział Rękopisów, Biblioteka Cyfrowa Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego: Wrocław, Poland, 1750–1800; Volume 2, Available online: Oai:bibliotekacyfrowa.pl:14652 (accessed on 27 October 2020).

- Wernher, F.B. Silesia in Compendio Seu Topographia das ist Praesentatio und Beschreibung des Herzogthums Schlesiens [...] Pars I; Manuscript; BUWr Oddział Rękopisów, Biblioteka Cyfrowa Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego: Wrocław, Poland, 1750–1800; Volume 3, Available online: Oai:bibliotekacyfrowa.pl:15414 (accessed on 27 October 2020).

- Wernher, F.B. Topographia Seu Compendium Silesiae, Pars II […]; Manuscript; BUWr Oddział Rękopisów, Biblioteka Cyfrowa Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego: Wrocław, Poland, 1750–1800; Volume 4, Available online: oai:bibliotekacyfrowa.pl:16339 (accessed on 27 October 2020).

- Wernher, F.B. Topographia Seu Compendium Silesiae, Pars V [...]; Manuscript; BUWr Oddział Rękopisów, Biblioteka Cyfrowa Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego: Wrocław, Poland, 1750–1800; Volume 5, Available online: Oai:bibliotekacyfrowa.pl:16345 (accessed on 27 October 2020).

- Wernher, F.B. Topographia Silesiae, Münsterberg-Frankenstein, Schweidnitz, Freie Standesherrschaften; Manuscript; Rep. 135, Nr. 526-2; Geheimes Staatsarchiv Preußischer Kulturbesitz XVII. HA: Berlin, Germany, 1750–1800; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Wernher, F.B. Scenographia Urbium Silesiae; Hofmann: Nürnberg, 1737–1752; BUWr Oddział Starych Druków: Wrocław, Poland; Available online: Oai:bibliotekacyfrowa.pl:15058 (accessed on 27 October 2020).

- Bunzlau 2758 [New Nr 4759], Topographische Karte (Messtischblatt) Ostdeutschland 1: 25,000; Map; Wydział Geografii i Studiów Regionalnych Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego; Königlich-Preussische Landesaufnahme: Berlin, Germany, 1888; Available online: http://maps.mapywig.org/m/German_maps/series/025K_TK25/4759_(2758)_Bunzlau_1888_UW.jpg (accessed on 27 October 2020).

- Trebschen 2192 [New Nr 3960], Topographische Karte (Messtischblatt) Ostdeutschland 1: 25,000; Map; BUWr; Reichsamt für Landesaufnahme: Berlin, Germany, 1896; Available online: https://www.bibliotekacyfrowa.pl/dlibra/publication/33891/edition/40950 (accessed on 27 October 2020).

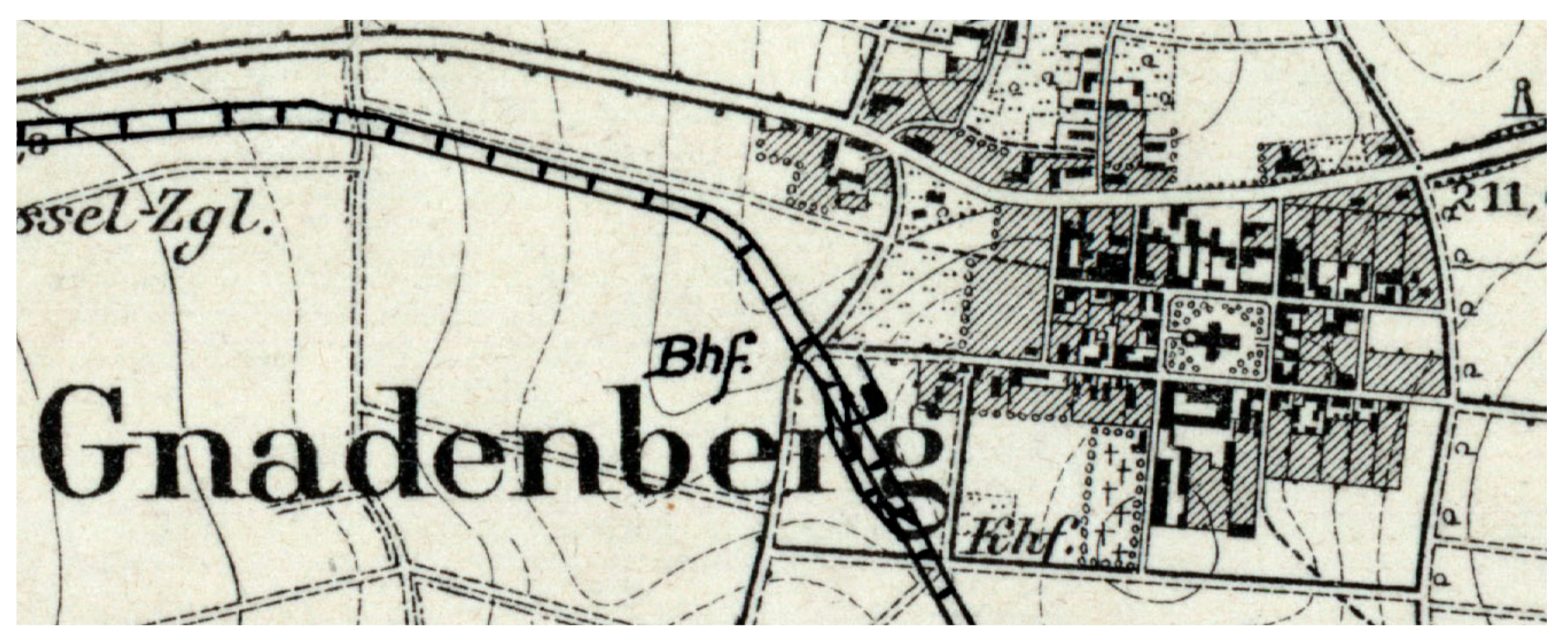

- Gnadenfrei 3135 [New Nr 5366], Topographische Karte (Messtischblatt) Ostdeutschland 1: 25,000; Wydział Nauk Geograficznych Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego, Biblioteka WNG; Königlich-Preussische Landesaufnahme: Berlin, Germany, 1900; Available online: http://maps.mapywig.org/m/German_maps/series/025K_TK25/5366_(3135)_Gnadefrei_1900_BWNG_UL.jpg (accessed on 27 October 2020).

- Halbau 2552 [New Nr 4457], Topographische Karte (Messtischblatt) Ostdeutschland 1: 25,000; Sächsische Landesbibliothek—Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Dresden (SLUB); Königlich-Preussische Landesaufnahme: Berlin, Germany, 1905; Available online: http://www.deutschefotothek.de/documents/obj/71054713 (accessed on 27 October 2020).

- Auras 2766 [New Nr 4767] Topographische Karte (Messtischblatt) Ostdeutschland 1: 25,000; Map; Reichsamt für Landesaufnahme: Berlin, Germany, 1916; Available online: https://www.bibliotekacyfrowa.pl/dlibra/publication/33753/edition/44017/content (accessed on 27 October 2020).

- Neusalz 2335 [New Nr 4160] Topographische Karte (Messtischblatt) Ostdeutschland 1: 25,000; Map; Reichsamt für Landesaufnahme: Berlin, Germany, 1922; Available online: http://maps.mapywig.org/m/German_maps/series/025K_TK25/4160_(2335)_Neusalt_1922_UW.jpg (accessed on 27 October 2020).

- Lucae, F. Schlesiens Curiose Denckwürdigkeiten Oder Vollkommene Chronica von Ober- und Nieder-Schlesien; Knoch: Franckfurt, Germany, 1689; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann, F.A. Beyträge zur Beschreibung von Schlesien; Bd. 7; Tramp Press: Brieg, Prussia, 1796; p. 100. [Google Scholar]

- Meissner, J.G. Kurze Beschreibung von Schlesien [...], 3rd ed.; 1795; Linsner: Bunzlau, Prussia, 1805; p. 111. [Google Scholar]

- Bratring, F.W. Statistisch-Topographische Beschreibung der Gesammten Mark Brandenburg; Maurer: Berlin, Prussia, 1809; Volume 3, p. 329. [Google Scholar]

- Schumann, F.A.; Schiffner, A. Vollständiges Staats- Post- und Zeitungslexikon von Sachsen; Schumann: Zwickau, Prussia, 1816; Volume 3, pp. 670–671. [Google Scholar]

- Boccacio, G. Decameron, (1470 ca); Laterza: Bari, Italy, 1927; p. 184. Available online: https://it.wikisource.org/wiki/Pagina:Boccaccio_-_Decameron_I.djvu/188 (accessed on 27 October 2020).

- Battisti, E. “Natura artificiosa” to “Natura artificialis”. In The Italian Garden; Coffin, D.R., Ed.; Dumbarton Oaks: Washigton, DC, USA, 1972; pp. 15–16. [Google Scholar]

- MacDougall, E.B. Fountains, Statues, and Flowers: Studies in Italian Gardens of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries; Dumbarton Oaks: Washigton, DC, USA, 1994; p. 97. [Google Scholar]

- Estienne, C. De re Hortensi Libellus; V. Lugduni: Paris, France, 1536; p. 19. [Google Scholar]

- Wimmer, K.A. Alleen—Begriffsbestimmung, Entwicklung, Typen, Baumarten. In Alleen in Deutschland; Lehmann, I., Rohde, M., Eds.; Edition Leipzig: Leipzig, Germany, 2006; pp. 14–23. [Google Scholar]

- Palladio, A. Delle vie, Cap. Primo. In I Quatro Libri dell Architettura; Venezia 1570; repr. Hoepli: Milano, Italy, 1945; pp. 262–266. Available online: https://www.liberliber.it/mediateca/libri/p/palladio/i_quattro_libri_dell_architettura/pdf/palladio_i_quattro_libri_dell_a.pdf (accessed on 27 October 2020).

- Braun, G.; Hogenberg, F. Brugae [Brugge]. In Flandricarum Urbium Ornamenta; Map; Bibliotheque Nationale de France, Gallica: Cologne, France, 1572; p. 625. Available online: http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b550045931.r=bruges.langEN (accessed on 27 October 2020).

- Braun, G.; Hogenberg, F. Harlemum, Sive ut Ha: Barlan Her:lemum Urbs Hollandia Famosa; The Barry Lawrence Ruderman Map Collection: La Jolla, CA, USA, 1575; Available online: https://exhibits.stanford.edu/ruderman/catalog/tt323th0524 (accessed on 27 October 2020).

- Braun, G.; Hogenberg, F. Gouda, Elegantiss Hollandiae Opp. ad Isalam Amnem, ubi Goudam flu. à Quo Oppidum Nomen Habet, Absorbet 1585; The Allard Pierson in Focus: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1588; Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/11245/3.163 (accessed on 27 October 2020).

- Braun, G.; Hogenberg, F. Campia. Campen; Zuiderzeemuseum Enkhuizen: Enkhuizen, The Netherlands, 1589–1635; Available online: https://www.zuiderzeecollectie.nl/object/collect/Zuiderzee_museum-3041 (accessed on 27 October 2020).

- Kaart Met Stadsmuren Voor Den Haag; Holland Nationaal Archief: The Hague, The Netherlands, 1530. Available online: https://geschiedenisvanzuidholland.nl/collecties/kaart-met-stadsmuren-voor-den-haag-1530- (accessed on 27 October 2020).

- Londerseel van, J. Lange Voorhout, Vogelvlucht; engraving; Rijksdienst voor het Cultureel Erfgoed: Amersfoort, The Netherlands, 1614; Available online: https://beeldbank.cultureelerfgoed.nl/rce-mediabank/detail/4bdf0d89-bd02-71fe-92d6-be6309b8c39a/media/98b4d8bf-207a-f1d8-bb1b-91e968f23e69?mode=detail&view=horizontal&q=20085921&rows=1&page=1&sort=order_s_objectnummer%20asc (accessed on 27 October 2020).

- Blaeu, J. Het Voorhout Haga Comitis Vulgo’s Graven-Hage. In Blaeu’s Toonneel der Steden; Delft University of Technology: Delft, The Netherlands, 1649; Available online: https://repository.tudelft.nl/view/MMP/uuid:4985aa39-66cd-4649-97c9-5f8e2f383784 (accessed on 27 October 2020).

- Mourik van, P.; Veen van der, G. Langs Haagse Bomen; Eburon Uitgeverij, B.V.: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2013; p. 17. ISBN 9059727320. [Google Scholar]

- Lange Voorhout. In Het Lange Voorhout: Monumenten, Mensen en Macht; Wijsenbeek-Olthuis, T. (Ed.) Geschiedkundige Vereniging Die Haghe: Zwolle/Waanders/Den Haag, The Nederlands, 1998; ISBN 90-400-9244-3. Available online: https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lange_Voorhout (accessed on 27 October 2019).

- Berckenrode, B.F. Plattegrond van Amsterdam (Blad Middenboven); Rijksprentenkabinet, Rijksmuseum: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1625; Available online: https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/collection/RP-P-1892-A-17491A (accessed on 27 October 2020).

- Braun, G.; Hogenberg, F. Civitates Orbis Terrarum, Liber Primus; Coloniae Agrippinae. Map; BUWr Oddział Zbiorów Kartograficznych: Wrocław, Poland, 1612; pp. 46–47. Available online: https://www.bibliotekacyfrowa.pl/dlibra/publication/31483/edition/110258/content (accessed on 27 October 2020).

- Blaeu, W.J. Roma (1663). In Het Nieuw Stede Boek van Italie, Ofte Naauwkeurige Beschrijving van Alle Deszelfs Steden, Paleyzen, Kerken &c., Nevens de Land-Kaarten van Alle Deszelfs Provincien; map; Mortier, C.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Utrecht University Library: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 1704; p. 4A. Available online: https://objects.library.uu.nl/reader/viewer.php?obj=1874-36121&pagenum=9&lan=en (accessed on 27 October 2020).

- Merian, M. Reims En Champagne. In Topographia Galliae; Map; Merian: Franckfurt/Koblenz, Germany, 1655; p. 24C. Available online: LandesbibliothekszentrumRheinland-Pfalz2011pdf (accessed on 27 October 2020).

- Schaber, W. Schloss Hellbrunn und die Hellbrunner Allee. In 400 Jahre Hellbrunner Allee; Gföllner, K., Ed.; Samson Druck: Salzburg, Germany, 2015; pp. 7–13. ISBN 978-3-85015-282-2. Available online: https://www.salzburg.gv.at/kultur_/Documents/Publikationen/400_Jahre_Hellbrunner_Allee_online_2.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- Schlager, G. Salzburger Baumschutzverordnung 1992—Wunsch und Wirklichkeit. Nat. Landsch. 1993, 68, 302–307. [Google Scholar]

- Clundert, [ca 1632]; Blaeu, J.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1649–1652; Map. Rijksprentenkabinet, Rijksmuseum: Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Available online: https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/collection/RP-P-AO-14-61-1 (accessed on 3 December 2020).

- Willemstadt, 1632; Blaeu, J.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1649–1652; Map. Rijksprentenkabinet, Rijksmuseum: Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Available online: https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/collection/RP-P-AO-14-62 (accessed on 3 December 2020).

- Falda, G.B. Novissima et Accuratissima Delineatio Romae Veteris et Novae; map; Feuille de la, J.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; The Getty Research Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1690; Available online: https://rosettaapp.getty.edu/delivery/DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_pid=FL2115639 (accessed on 3 December 2020).

- de Vaugondy, G.R.; Delamarche, C.F. Plan Geometral De Paris Et De Ses Fauxbourgs; map; A Paris: Chez Delamarche, Géog., Rue du Foin St. Jacques, au Collège de Mtre; Gervais: Paris, France, 1797; Available online: https://collections.leventhalmap.org/search/commonwealth:6w924q228 (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- Waltern, J.F. Die Konigl. Preus. u. Churf. Brandenburg. Residenz-Stadt Berlin; Homann: Nuremberg; [1740 ca]; map. Zentral- und Landesbibliothek Berlin: Berlin, Germany. Available online: https://digital.zlb.de/viewer/toc/15453578/1/-/ (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- Faber, J.H. Topographische, Politische und Historische Beschreibung der Reichs- Wahl- und Handelsstadt Frankfurt am Mayn; Jäger: Frankfurt, Germany, 1788; Volume 1, pp. 25–61. [Google Scholar]

- Seutter, M. Topographia Sedis Imperatoriæ Moscovitarum Petropolis Anno 1744 Jam Publici Juris Facta; Map; BnF Gallica: Augsburg, Germany, 1744; Available online: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b530395167 (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- Fischer, J.B. Geschichte und Beschreibung der Markgräfl.-Brandenb. Haupt- & Res. Stadt Anspach; Fischer: Neu-Anspach, Germany, 1786; p. 32. [Google Scholar]

- Heinritz, J.G. Geschichte der Stadt Bayreuth (in drei Teilen); Bayreuth, 1823; Reed. Stadtarchiv Bayreuth: Bayreuth, Germany, 2019; Volume 1, pp. 56–57. Available online: https://www.bayreuth.de/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Heinritz_Geschichte-der-Stadt-Bayreuth.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- Decret No. 96 Berlin 26 Nov. 1746. In Novum Corpus Constitutionum Prussico-Brandenburgensium; Königl. Preußische Acad. der Wiss.: Berlin, Germany, 1771; Volume 4, p. 614. Available online: https://www.bayreuth.de/rathaus-buergerservice/stadtverwaltung/zahlen-fakten-2/stadtgeschichte/bayreuther-stadtgeschichte/ (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- Gottlieb Beckmann, J. Edickt wegen Satzung Weiden und Linden. Ed. 10 Juli 1743. In Beyträge zur Verbesserung der Forstwissenschaft; Beckmann, J.G., Ed.; Bd. 3; Stossel: Chemnitz, Germany, 1763; p. 183. [Google Scholar]

- Edict XXXII, Berlin 13 November 1742. Edict XXXII, Berlin 13 November 1742. Corpus Constitutionum Marchicarum, Continuatio II. Derer in der Chur- und Marck Brandenburg, Auch Incorporirten Landen, Ergangenen Edicten, Mandaten, Rescripten, von 1741. Biß 1744. Inclusive. 1744, p. 83. Available online: https://web-archiv.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/altedrucke.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/Rechtsquellen/CCMC2/start.html?image=06351&size=1 (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- Pfeiffer von, J.F. Vermischte Verbeßrungsvorschläge und freie Gedanken über Verschiedene, den Nahrungszustand, die Bevölkerung und Staatswirtschaft der Deutschen, betreffende Gegenstände; In der Eßlingerischen Buchhandlung: Frankfurt, Germany, 1778; Volume 1, pp. 60–70. [Google Scholar]

- Verordnung wegen der Maulber-Baume […]. 16 August 1765. In Novum Corpus; Königl. Preußische Acad. der Wiss.: Berlin, Germany, 1766; Volume 3, p. 1008.

- Sturm, L. Geschichte der Stadt Goldberg in Schlesien; Sturm: Goldberg, Prussia, 1888; p. 409. [Google Scholar]

- Kunz, H. Das Schloss der Piasten zum Briege; Bänder: Brieg, Prussia, 1885. [Google Scholar]

- Bimler, K. Das Piastenschloss zu Brieg; Maruschke und Berendt: Breslau, Germany, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Zlat, M. Zamek piastowski w Brzegu; Instytut Śląski w Opolu: Opole, Poland, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Zlat, M. Brama zamkowa w Brzegu. Biul. Hist. Szt. 1962, 24, 284–322. [Google Scholar]

- Schönwälder, K.F. Geschichtliche Ortsnachrichten von Brieg und Seiner Umgebung; Kern: Brieg, Prussia, 1847; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Grund Oder Abris der Stad Grosglogau; [1618–1632]; map. BUWr Oddział Zbiorów Kartograficznych: Wrocław, Poland. Available online: Oai:bibliotekacyfrowa.pl:37485 (accessed on 27 October 2020).

- Boras, Z. Książęta Piastowscy Śląska; Wyd. Śląsk: Wrocław, Poland, 1972; p. 456. [Google Scholar]

- Aigentliche Vorbildung der Vestung Brieg Wie Selbte Gelegen und Mit Ihren Bollwercken Versehen; BUWr Oddział Zbiorów Kartograficznych: Wrocław, Poland. Available online: http://www.bibliotekacyfrowa.pl/dlibra/publication/28379?tab=1 (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- Bimler, K. Das Piastenschloss zu Ohlau; Maruschke und Berendt: Breslau, Germany, 1936. [Google Scholar]

- Lutsch, H. Verzeichnis der Kunstdenkmäler der Provinz Schlesien; Korn: Breslau, Prussia, 1889; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Eysymontt, R. Architektura miasta Oławy. In Oława; Eysymontt, R., Ed.; Institute of Archeology and Ethnology of the Polish Academy of Sciences: Wrocław, Poland, 2015; Volume 4, pp. 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Geissler, K.G. Situations Plan F. Von dem Königs Schloss zu Ohlau; Eysymontt, R., Atlas Historyczny Miast Polskich, Czaja, R., Śląsk, Młynarska-Kaletynowa, M., Eds.; Institute of Archeology and Ethnology of the Polish Academy of Sciences: Wrocław, Poland, 2015; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Säbisch, V. Plan of Bastion Fortifications of Oława; Eysymontt, R., Atlas Historyczny Miast Polskich, Czaja, R., Śląsk, Młynarska-Kaletynowa, M., Eds.; Institute of Archeology and Ethnology of the Polish Academy of Sciences: Wrocław, Poland, 2015; Volume 4, p. 44. [Google Scholar]

- Ohlau. Gezeichnet von Hauptmann Chalaupka. 1 gez. Blatt (Kopie); Atlas Historyczny Miast Polskich; Eysymontt, R.; Czaja, R.; Śląsk; Młynarska-Kaletynowa, M. (Eds.) Institute of Archeology and Ethnology of the Polish Academy of Sciences: Wrocław, Poland, 2015; Volume 4, p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Wernher, F.B.; Engelbrecht, M. Arx Olavie in Silesia In Views of Cistercian Monasteries and Palaces of Lower Silesia; [Augsburg?]; BUWr Oddział Starych Druków: Wrocław, Poland, 1739; p. 38. Available online: https://www.bibliotekacyfrowa.pl/dlibra/publication/10927/edition/69639/content (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- Wissmach, E. Die Stadt Ohlau und ihre Umgebung; Magistr. der Stadt Ohlau: Ohlau, Germany, 1929; pp. 22–24. [Google Scholar]

- Eysymontt, R. Rozwój przestrzenny, architektura, sztuka. In Wołów. Zarys Monografii Miasta; Kościk, E., Ed.; Silesia: Wrocław/Wołów, Poland, 2002; pp. 154–198. ISBN 83-85689-99-0. [Google Scholar]

- Sinapius, J. Olsnographia oder Eigentliche Beschreibung des Oelsnischen Fürstenthums In Nieder-Schlesien welche in zwey Haupt-Theilen so wohl insgemein Dessen Rahmen, Situation, Regenten Religions-Zustand, [...] Ausgefertiget von Johanne Sinapio, [...]. T.1; Brandenburger: Leipzig, Germany, 1706; Volume 2, pp. 516–519. [Google Scholar]

- Bimler, K. Die Schlesischen Massiven Wehrbauten, Fürstentum Oels—Wohlau; Kommission Heydebrand: Breslau, Germany, 1942; Volume 3, pp. 22–30. [Google Scholar]

- Schulze, H. Die Succession im Fürstenthum Oels Beim Abgange der Ältem Linie des Hauses[…]; Korn: Breslau, Prussia, 1868; pp. 6–7. [Google Scholar]

- Herbst, G. Des Schlesischen Gärtners Lustiger Spatziergang. 1692. Available online: http://diglib.hab.de/wdb.php?dir=drucke/oe-283&distype=thumbs (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- Jenderich, C. Mahre eigentilische Abbildung […] Residenz in Bernstadt; Bernstadt, Germany, 1692; p. 414. [Google Scholar]

- Heinirch, A. Wallenstein als Herzog von Sagan; Goerlich & Coch: Breslau, Germany, 1896. [Google Scholar]

- Wernher, F.B. Das Fürstenthum Sagan in Nieder Schlesien; BUWr Oddział Zbiorów Kartograficznych: Wrocław, Poland, 1750; Available online: Oai:bibliotekacyfrowa.pl:37488 (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- Leipelt, A. Geschichte der Stadt und des Herzogthums Sagan...; Rauertsch: Sorau, Prussia, 1853; pp. 128–129. [Google Scholar]

- Kanold, J. Sammlung von Natur- und Medicin-, Wie Auch Hierzu Gehörigen Kunst- und Literatur Geschichten; Richter: Leipzig, Germany, 1726; pp. 747–753. [Google Scholar]

- Gierowski, J. Miasta, manufaktury. In Historia Śląska; Part 3; Maleczyński, K., Ed.; Ossolineum: Wrocław/Warszawa/Kraków, Poland, 1963; Volume 1, p. 214. [Google Scholar]

- Sammlung Der Wichtigsten Und Nöthigsten, Bisher Aber Noch Nicht Herausgegebenen Käyser- Und Königlichen Auch Hertzoglichen Privilegien, Statuten, Rescripten und Pragmatischen Sanctionen des Landes Schlesien: Aus den nach und nach publicirten Königlichen Ober-Amts-Patenten, wie auch aus den wichtigsten Landes-Cantzeleyen und Archiven. Bd. 2; Habsburg Empire: Breslau, Poland, 1739; Volume 2, pp. 423–424.

- Schmidt, F.J. Geschichte der Stadt Schweidnitz; Heege: Schweidnitz, Prussia, 1846; Volume 2, p. 300. [Google Scholar]

- Wernher, F.B.; Merz, J.G. Prospectus Templi Evangelici Extra Urbem Iauriam […]; engraving; Österreichische Nationalbibliothek: Wien, Austria, 1735; Available online: Oai:baa.onb.at:19191100 (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- Festungsplan von Schweidnitz. In Befestigungsentwürfe für die Stadt Schweidnitz; Walrave, G.C.; Sers, L.P.; Enbers, W.; Foris, F.A.; Dariez (Eds.) Staatbibliothek Berlin: Berlin, Germany, 1743–1748. [Google Scholar]

- Wernher, F.B.; Merz, J.G. Prospectus Templi Evangelici Extra Urbem Sanagum […]; Österreichische Nationalbibliothek: Wien, Austria, 1735; Available online: Oai:baa.onb.at:19252904 (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- Wernher, F.B.; Merz, J.G. Prospectus Templi Evangelici Extra Urbem Hirschbergam in Silesia Inferiore, Cui Nomen ad Crucem Christi. Prospect der Evangelischen Kirche vor der Stadt Hirschberg, in Nider Schlesien, genandt zum Creutz-Christi. 1709; Österreichische Nationalbibliothek: Wien, Austria, 1735; Available online: Oai:baa.onb.at:13889693 (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- Plan de la Bataille de Breslau 1757; Map; Hond: Paris, France, 1758; Available online: https://polska-org.pl/915320,foto.html?idEntity=554891 (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- Bataille De Breslau 22. Nov. 1757. In Collection de Quarante Deux Planes de Batailles, Sieges et Affaires les Plus Memorables de la Guerre de Sept Ans […]; map; Roesch, J.F. (Ed.) Jaeger: Franckfurt, Germany, 1790; Available online: https://polska-org.pl/831827,foto.html?idEntity=554891 (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- Plan vor den Gegend und den Draeffen Welche un die Stadt Breslau Bis Lissa Hin Ligen, 1756, map. Available online: https://polska-org.pl/632755,foto.html?idEntity=3571227 (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- Breslau, 270, Topographische Karte, Pruss.Generalstab, 1826–1831, Hosse: [Breslau] 1832, with Changes from 1856, map. Available online: https://polska-org.pl/7902794,foto.html?idEntity=3571227 (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- Breslauer Regierungs Bezirk. 1828–1831. Available online: oai:kpbc.umk.pl:171533 (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- Grundriss der Königl. Prusisch. und Herzogl. Schlesischen Haupt-Stadt Bresslau; map; BUWr Oddział Zbiorów Kartograficznych: Wrocław, Poland, 1750; Available online: Oai:bibliotekacyfrowa.pl:42002 (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- Herold, J. Von Scheitnig und Seinem Parke, dem “Fürstengarten”: Eine Ortsgeschichtliche Darstellung; Trewendt & Granier: Breslau, Germany, 1913; p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Sinapius, J. Schlesische Curiositäten Erste Vorstellung, Darinnen die Ansehnlichen Geschlechter Des Schlesischen Adels; Sinapius: Leipzig, Germany, 1720; p. 344. [Google Scholar]

- Foerster, A. Geschichtliches von den Dörfern des Grünberger Kreises; Weller: Grünberg, Germany, 1905; p. 207. [Google Scholar]

- Hinz, B. Die Schöppenbücher der Mark Brandenburg: Besonders des Kreises Züllichau -Schwiebus; Gerd, H., Ed.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 1964; pp. 88, 153. [Google Scholar]

- Worbs, J.G. Geschichte des Herzogthums Sagan; Frommann: Züllichau/Sagan, Prussia, 1795; pp. 90, 395. [Google Scholar]

- Knie, J.G. Alphabetisch-Statistisch-Topographische Übersicht der Dörfer, Flecken, Städte und andern Orte der Königl. Preuß. Provinz Schlesien; Graß, Barth und Co.: Breslau, Prussia, 1845. [Google Scholar]

- Sinapius, J. Des Schlesischen Adels Anderer Theil, Oder Fortsetzung Schlesischer Curiositäten: Darinnen Die Gräflichen, Freyherrlichen und Adelichen Geschlechter, So Wohl Schlesischer Extraction, Als auch Die aus Andern Königreichen und Ländern in Schlesien Kommen, Und Entweder Darinnen Noch Floriren, Oder Bereits Ausgangen, Jn Völligen Abrisse Dargestellet Werden, Nebst Einer Nöthigen Vorrede und Register; Rohrlach: Leipzig, Germany; Breslau, Poland, 1728; p. 178. [Google Scholar]

- Simonetti, Giulio. In Allgemeines Lexikon der Bildenden Künstler von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart. Begründet von Ulrich Thieme und Felix Becker; Vollmer, H. (Ed.) Siemering–Stephens; Seemann, E.A.: Leipzig, Germany, 1937; Volume 31, p. 73. [Google Scholar]

- Kalinowski, K. Architektura Doby Baroku na Śląsku; Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe: Warszawa, Poland, 1977; p. 132. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, H. Katasterkarte Halbau; Map; Technische Universität Berlin: Berlin, Germany, 1907; Available online: https://architekturmuseum.ub.tu-berlin.de/index.php?p=79&POS=2 (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- Halbau 2552 [New Nr 4457], Topographische Karte (Messtischblatt) Ostdeutschland 1: 25,000; Königlich-Preussische Landesaufnahme: Berlin, Germany, 1939. Available online: https://www.bibliotekacyfrowa.pl/dlibra/publication/33832/edition/42477 (accessed on 27 October 2020).

- Lindenstrasse, Halbau. 1900. Available online: https://polska-org.pl/8185306,foto.html?idEntity=599261 (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- Zollner, J.F. Briefe über Schlesien, Krakau, Wieliczka und die Grafschaft Glätz aufeiner Reise im Jahr 1791, Berlin, 1792. Konopnicka, M. tr. In Źródła i Materiały do Dziejów Środkowego Nadodrza; Bartkiewicz, K., Ed.; Pedagogical University of Tadeusz Kotarbiński in Zielona Góra: Zielona Góra, Poland, 1996; pp. 103–104. [Google Scholar]

- Grüß aus Neusalz, Bresslauer Strasse, Postcard; Bohm: Neusalz, Germany, 1900; Available online: https://polska-org.pl/912284,foto.html?idEntity=596123 (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- Mettele, G. Weltbürgertum oder Gottesreich: Die Herrnhuter Brüdergemeine Als Globale Gemeinschaft 1727–1857; Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht: Göttingen, Germany, 2009; pp. 49–54. ISBN 978-3-525-36844-2. [Google Scholar]

- Karczyńska, H. Odnowiona Jednota Braterska w XVIII-XX w.; Semper: Warszawa, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Battek, M.J. Ansiedlung der Unitäts-Brüder in Schlesien. Available online: https://docplayer.org/50866439-Ansiedlung-der-unitaets-brueder-in-schlesien-und-ihre-spuren.html (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- Lewis, M.J. City of Refuge: Separatists and Utopian Town Planning; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA; Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 22–113. ISBN 13 9780691171814. [Google Scholar]

- Neudecker, C.G. Geschichte des Evangelischen Protestantismus in Deutschland; K.F. Köhler: Leipzig, Prussia, 1845; Volume 2, pp. 646–655. [Google Scholar]

- Keyl, M.; Krause, I.G. Grundriss und Prospecte der Drey Evangelischer Bruder Gemein Orte in Marggraffthum Ober Lausitz, Herrnhut, Nisky, Klein-Welke: [gewidmet:] Reichsgrafen zu Reuss Heinrich den XXVIII,...; Sächsische Landesbibliothek—Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Dresden (SLUB), Kartensammlung: Dresden, Germany, 1782; Available online: http://www.deutschefotothek.de/documents/obj/70400307 (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- Reuter, P.C. Herrenhaag; Moravian Archive: Winston-Salem, NC, USA, 1760; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/P-C-G-Reuter-Herrnhag-nd-Courtesy-of-the-Moravian-Archives-Winston-Salem-North_fig4_265839817 (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- Reuter, P.C. Nieska; Moravian Archive: Winston-Salem, NC, USA, 1760; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/P-C-G-Reuter-Nieska-1760-Courtesy-of-the-Moravian-Archives-Winston-Salem-North_fig5_265839817 (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- Brandt, A.L. Büdingen Herrnhaag; SLUB: Dresden, Germany, 1755; Available online: https://www.slub-dresden.de/ueber-uns/buchmuseum/ausstellungen-fuehrungen/archiv-der-ausstellungen/ausstellungen-2010/die-welt-in-herrnhut/herrnhut-impressionen/ (accessed on 27 November 2020).

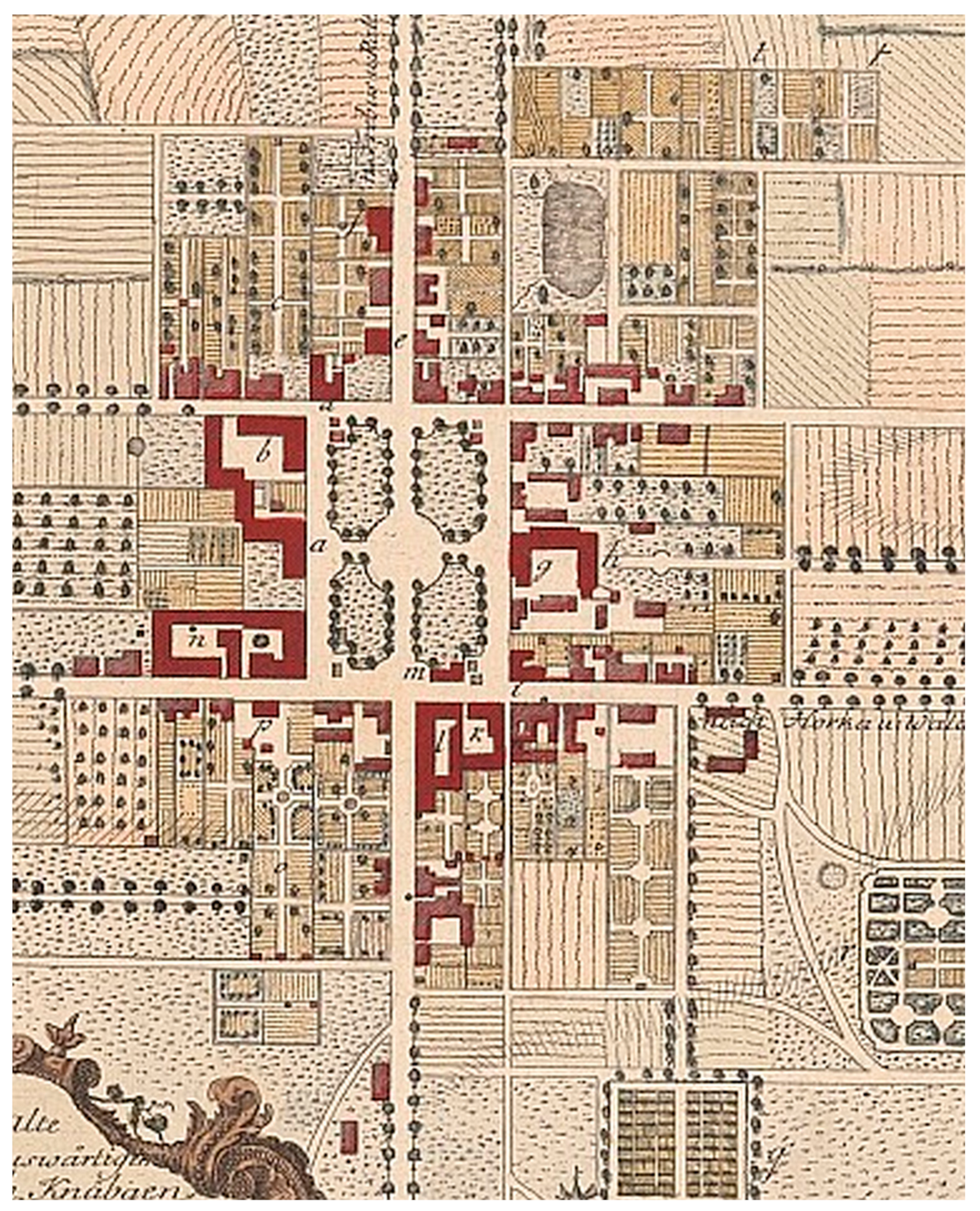

- Brandt, A.L. Gnadenfrei; SLUB: Dresden, Germany, 1755; Available online: https://www.slub-dresden.de/ueber-uns/buchmuseum/ausstellungen-fuehrungen/archiv-der-ausstellungen/ausstellungen-2010/die-welt-in-herrnhut/herrnhut-impressionen/ (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- Brzezowski, W. Ślązacy a teoria sztuki ogrodniczej od XVI do XVIII w. w świetle zbiorów Biblioteki Uniwersyteckiej we Wrocławiu, The Silesians and theories of garden art from the 16th to the 18th century with new research from the Wrocław University Library collection. Architectus 2013, 33, 5–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szilágyi, K.; Lahmer, C.; Szabó, K. Allées in Landscape Architecture and Garden. Art—Types, Preservation, and Renewal of the Living. Heritage of Baroque Allées in Hungary. Land 2020, 9, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ludwig, B. Baroque Origins of the Greenery of Urban Interiors in Lower Silesia and the Border Areas of the Former Neumark and Lusatia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2623. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052623

Ludwig B. Baroque Origins of the Greenery of Urban Interiors in Lower Silesia and the Border Areas of the Former Neumark and Lusatia. Sustainability. 2021; 13(5):2623. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052623

Chicago/Turabian StyleLudwig, Bogna. 2021. "Baroque Origins of the Greenery of Urban Interiors in Lower Silesia and the Border Areas of the Former Neumark and Lusatia" Sustainability 13, no. 5: 2623. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052623

APA StyleLudwig, B. (2021). Baroque Origins of the Greenery of Urban Interiors in Lower Silesia and the Border Areas of the Former Neumark and Lusatia. Sustainability, 13(5), 2623. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052623