Achieving Social and Ecological Outcomes in Collaborative Environmental Governance: Good Examples from Swedish Moose Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

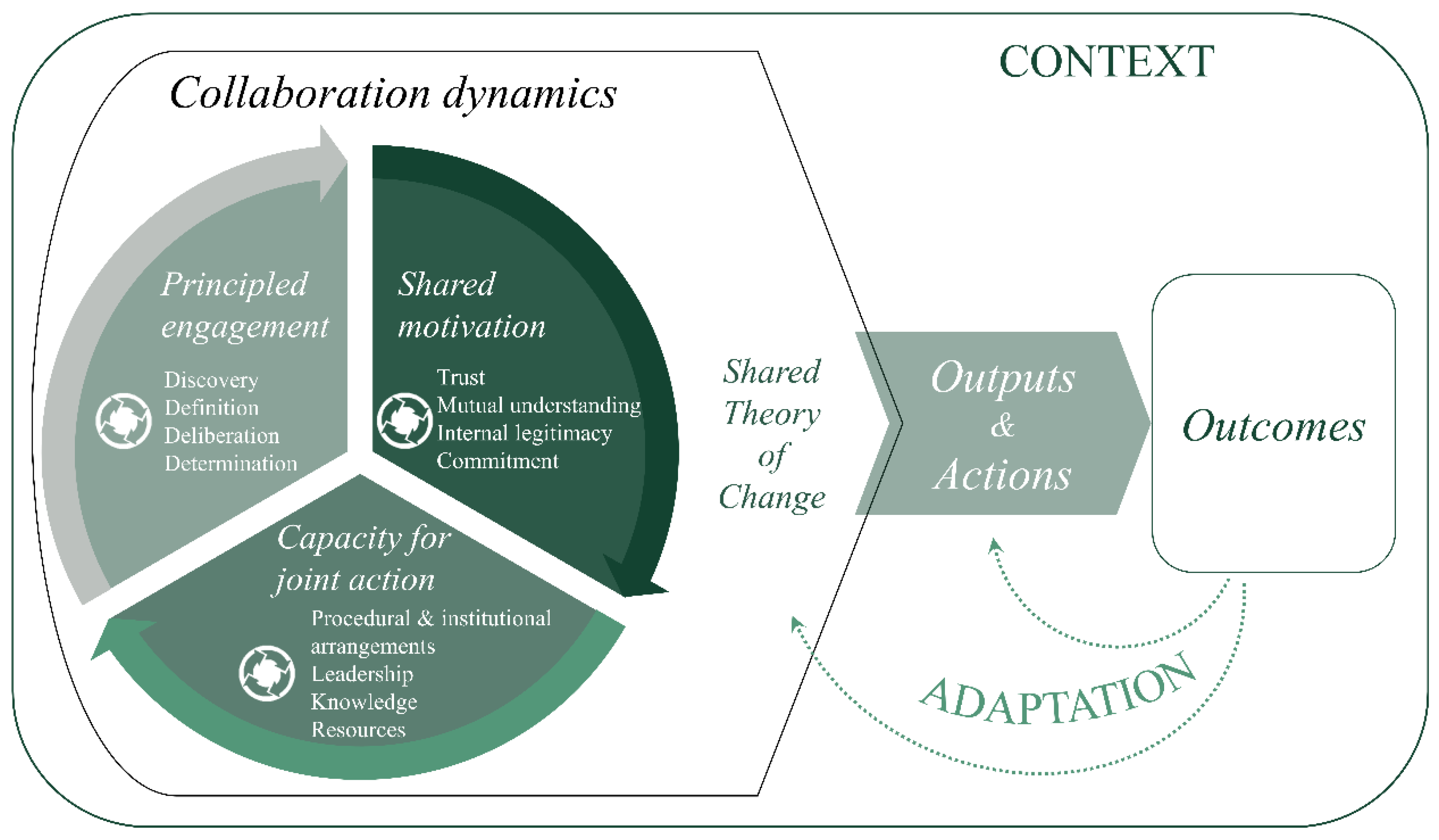

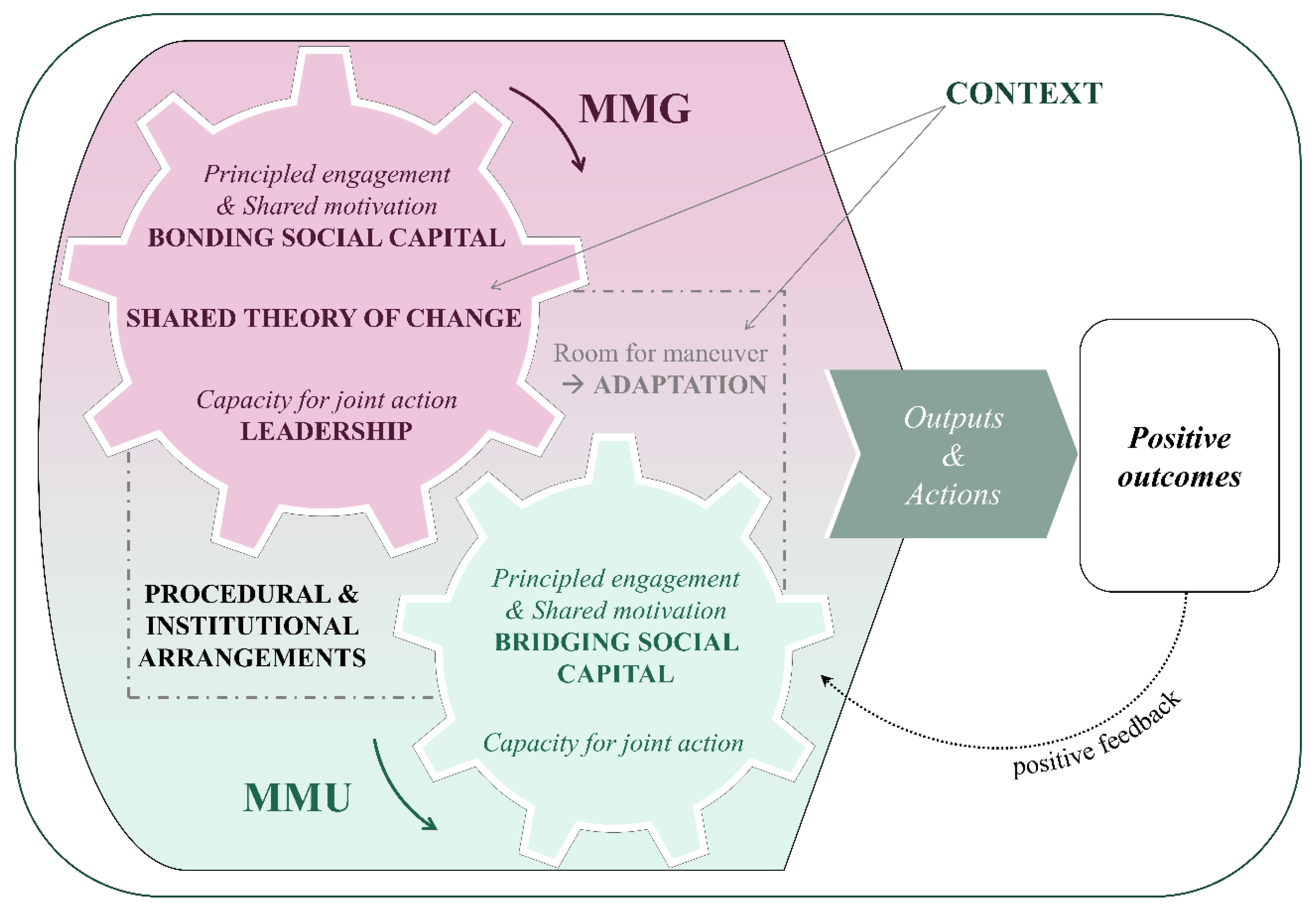

1.1. Analytical Framework

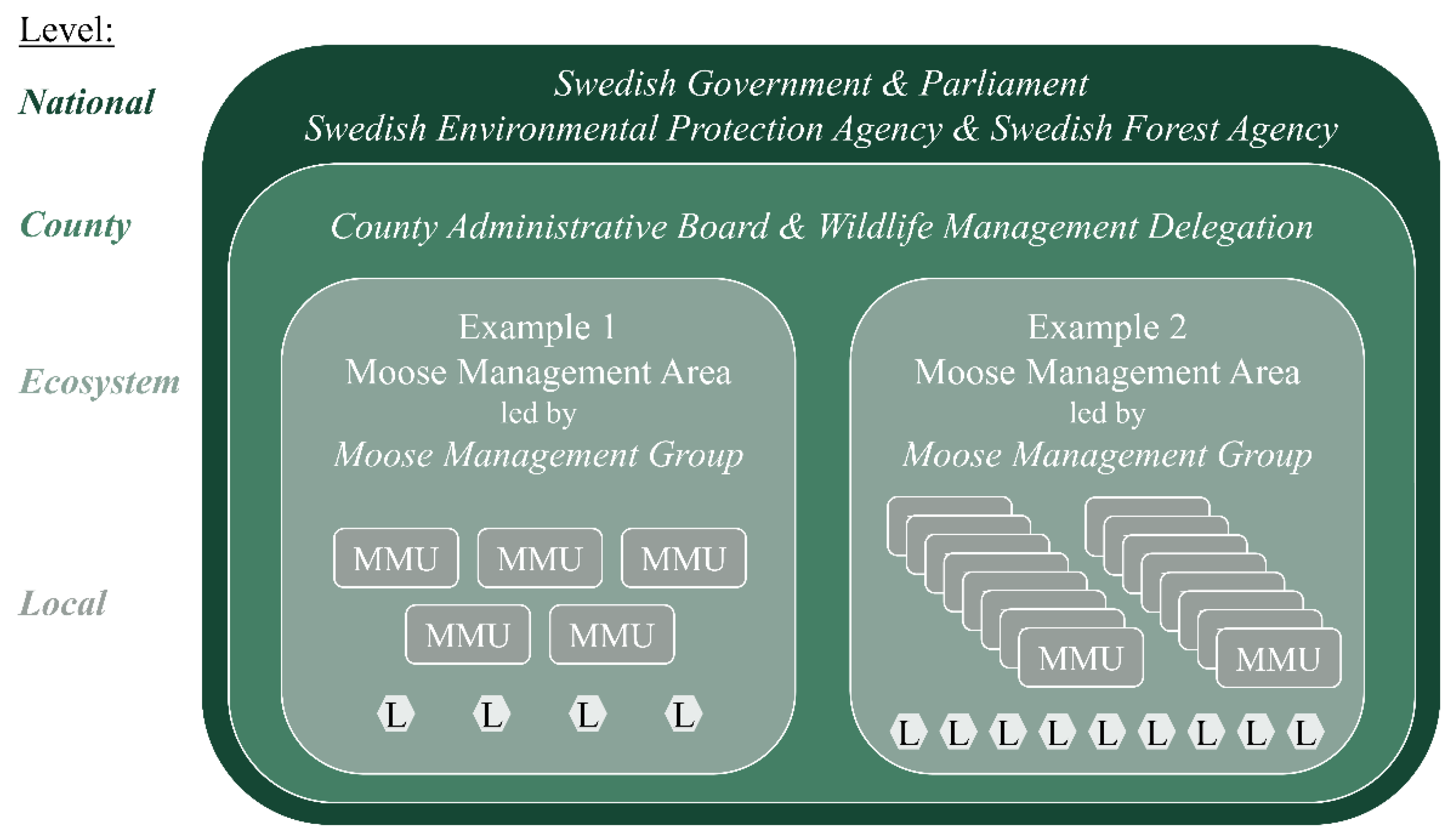

1.2. Study Context

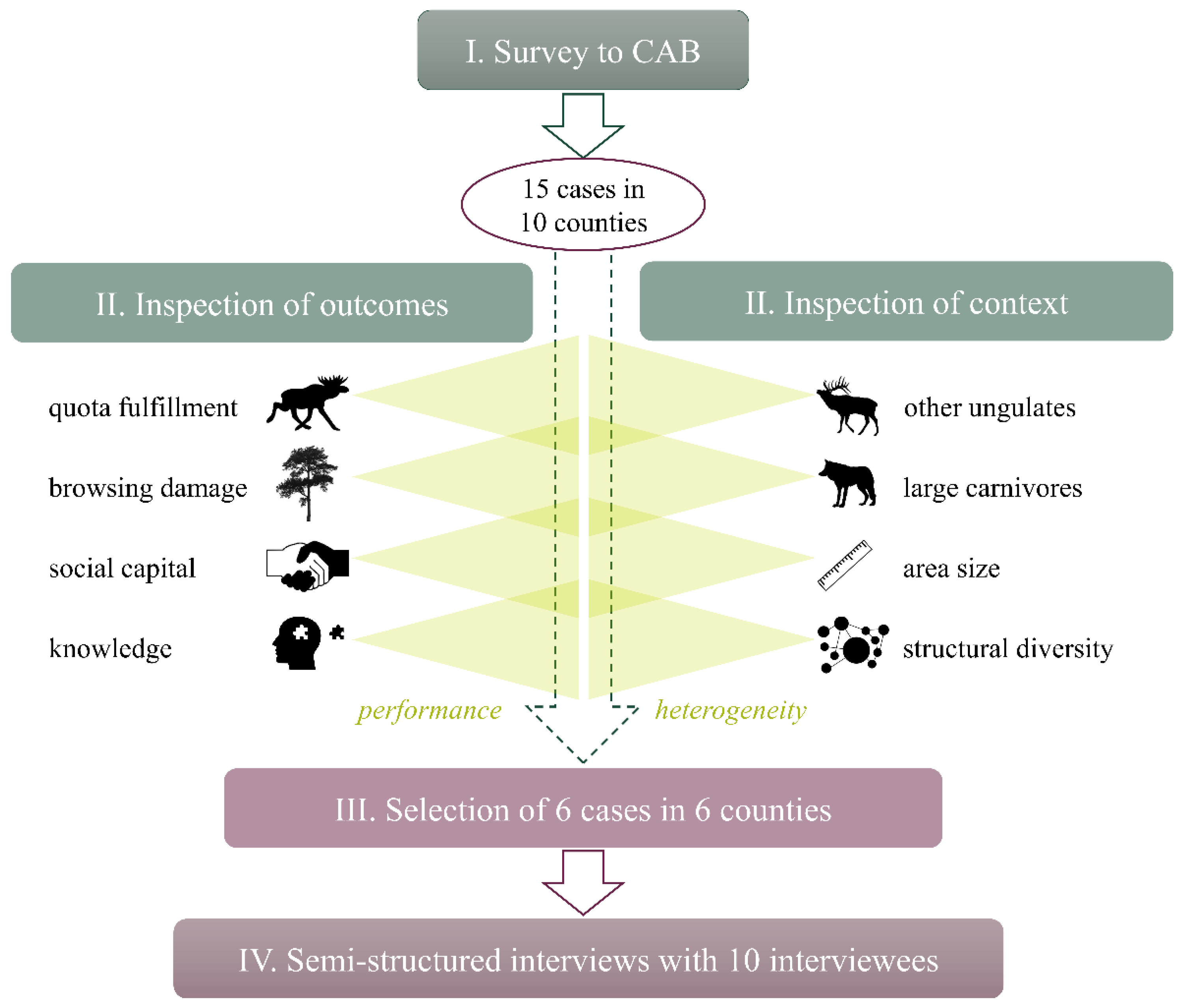

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Selection

2.2. Recruitment Process and Interviews

2.3. Thematic Analysis of the Qualitative Data

3. Results

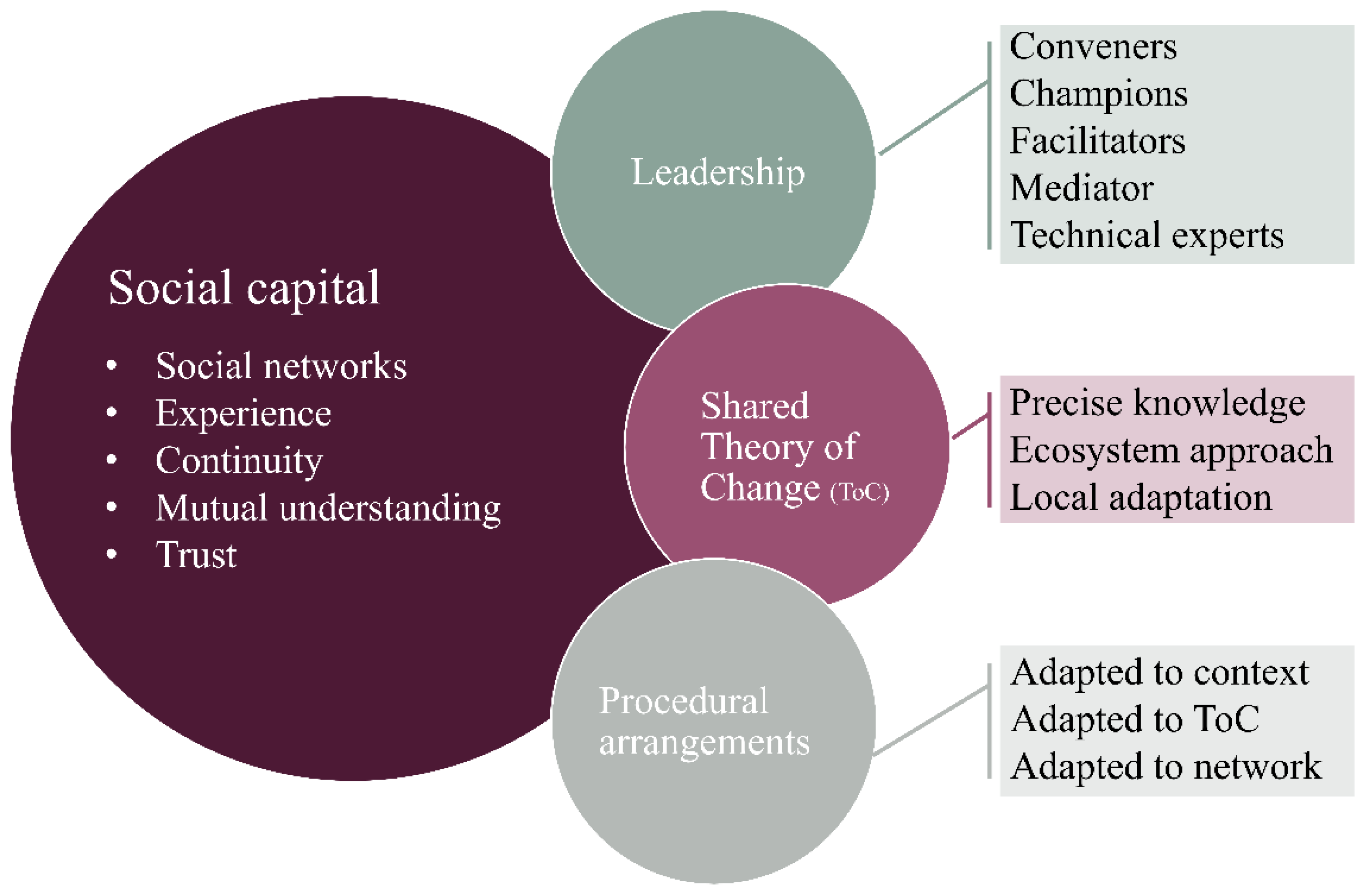

3.1. Commonalities among ‘Good Examples’

“... in this area there are many who know each other from before and have an interest in it [relevant management issues]. I don’t know what to say about it, but I feel that many have, that we have contacts, maybe not directly meeting each other or being on the same boards, but we still know each other in some way and have an understanding. We were not unknown to each other from the beginning, but in some way, there is someone, we had some contact, and we have a feeling of how things are.”(Interview 1, landowner representative)

“When it comes to knowledge about monitoring methods, we probably have general knowledge, but of course this is specialized knowledge. But we have X, who is very good at this and can calculate equations by himself without the help of the hunting association and others. It has an effect that we have someone who is very good with this... The rest of us may not have such great knowledge, but it is enough that one has this knowledge and that you can delegate to and trust the one who has the knowledge.”(Interview 1, landowner representative)

“... we are all, so to say, results-oriented people, ... and we have always understood each other’s way of being, even though we are so different. And that has done a lot I believe, because we have achieved results quite quickly in our way of working. We don’t have, and we don’t need to have, confrontations just for the sake of it, but rather we know where we are from the beginning and then we go from there.”(Interview 2, landowner representative)

“… when we’re out visiting the MMUs and participate in their collaboration meetings, or in general when we are acting outwards [of the group], we are always a landowner and a hunter representative together. This simply shows that we have talked with each other before. They can never drive a wedge between us when we’re out.”(Interview 3, landowner representative)

“... the landowner side maybe had meetings and we got opportunities to participate from the hunter side, or the other way around so landowners got to know how the hunter side sees things. So, we had an open dialogue all the time really, and did not need to prevaricate or argue about anything, and I believe it was good that it was open. We’ve also taken this with us to the MMUs and License areas really, so this is how we work the whole time. And I strongly believe that it has become clear to us and them, wherever we’ve been, X and I and the others, we discovered in different places that this was the way to go.”(Interview 2, hunter representative)

3.2. Variation among ‘Good Examples’

3.2.1. Leadership

“We’re often invited to consultation meetings out in the Moose Management Units and we often act as chairperson or something, because they think it’s nice that there will be outsiders.”(Interview 3, landowner representative)

“… we’ve been available all the time, really, when they run into worries and stuff. We’ve tried to address it, and things we don’t know anything about, we try to find out. So, we try to be very accessible all the time to help them... I feel it’s a winning concept then, so you almost don’t dare to stop it really, because it works well, really.”(Interview 2, hunter representative)

3.2.2. Shared Theory of Change

“When we make our MMU and MMA plans we try to take in as many facts as we can, so there are no doubts. It’s facts that we base it on all the time like Älgobs [moose observations], pellet counts, harvest statistics, age assessment, calf weights, reproduction, browsing pressure and even ÄBIN [browsing inventory].”(Interview 4, landowner representative)

“Then we have a guy, a hunter representative on our board, who keeps incredible statistics on everything and among other things age assessment... been doing it for about 20 years... It’s a thing that’s very valuable and we’re probably quite unique with here I think... that we have a long history of this. So that’s how we go about it then.”(Interview 4, landowner representative)

“… we have actually, both internally and externally, discussed holism in a completely different way than in areas where it’s been decided to just manage moose, which is our formal assignment. We have a holistic perspective when we formulate our management plans, we have it in the discussions with the CAB and you could say that it’s heavily reflected in our discussions with the MMUs.”(Interview 2, landowner representative)

“Because it’s such a large area, you have to work in a slightly different way … it’s important to include people who have local knowledge of all parts of the management area. Because we have large management areas, we all know the management area generally, but when it comes to the details, it’s usually someone who knows better than anyone else and then you have to trust that person more.”(Interview 5, landowner representative)

“There you have to have a feeling for the area, so you know in this part of the management area we have a higher moose population than in this other part. So, these two MMU plans cannot both harmonize or be exactly the same as the management plan, rather here it must be higher and here it may have to be lower than in the management plan.”(Interview 5, landowner representative)

“We need better tools. We work a lot with local inventories, pellet counts, browsing inventories, and we’re trying to get an App, to collect data in the field … With all due respect to ÄBIN, it describes the management area overall and it’s very, very difficult for people out in the MMUs to absorb that information. They say, ‘No, I don’t recognize my home area when I read ÄBIN’. But if they’ve done this browsing inventory we’re trying to introduce, they look with completely different eyes in the forest.”(Interview 3, landowner representative)

“We don’t just look at developments over a year, we look at trends and in which direction we’re heading. Because you also have to work long-term [...] when working with nature, there are both variations and annual variability. Like, it’s probably part of life that we’ll have to live with that we have some variations. But the important thing is that we stick to the long-term goal and don’t tinker with it.”(Interview 3, landowner representative)

3.2.3. Procedural Arrangements

“... an important factor was the introduction of a mentoring system in which each member of the MMG has responsibility for one or a few management units to especially assist them, follow them, and help them with different things. I don’t think that’s been bad at all really. And then we compile this information in the group, and if someone has a little difficulty fixing it, we help out all the time, so we’ve been a good working group in the management group, I think we’ve been successful in that way too, in fact.”(Interview 2, hunter representative)

“I feel that we can get even better at this with local inventories and the fun thing is that there’s a lot of interest in it. So, we feel very strong support for this when we’re out, not least after the recent collaboration meeting we had. So many people have come back and discussed this and wanted to get us to their local collaboration meetings. Plus, I feel there’s a surprisingly large attendance at our education courses. And yet, I feel that we can’t really deliver everything, because we don’t have this inventory App ready and we don’t have everything to present really well and clearly. But this is still developing.”(Interview 3, landowner representative)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liberg, O.; Bergstrom, R.; Kindberg, J.; von Essen, H. Ungulates and their management in Sweden. In European Ungulates and Their Management in the 21st Century; Apollonio, M., Andersen, O., Putman, R., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010; p. 618. [Google Scholar]

- Danell, K.; Bergström, R.; Mattsson, L.; Sörlin, S. Jaktens Historia i Sverige: Vilt-Människa-Samhälle-Kultur; Liber AB: Stockholm, Sweden, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sandström, C.; Wennberg Di Gasper, S.; Öhman, K. Conflict resolution through ecosystem-based management: The case of Swedish moose management. Int. J. Commons 2013, 7, 549–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardell, Ö. Swedish Forestry, Forest Pasture Grazing by Livestock, and Game Browsing Pressure Since 1900. Environ. Hist. 2016, 22, 561–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boman, M.; Mattsson, L.; Ericsson, G.; Kriström, B. Moose Hunting Values in Sweden Now and Two Decades Ago: The Swedish Hunters Revisited. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2011, 50, 515–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallgren, M.; Bergström, R.; Bergqvist, G.; Olsson, M. Spatial distribution of browsing and tree damage by moose in young pine forests, with implications for the forest industry. Ecol. Manag. 2013, 305, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Månsson, J.; Kalén, C.; Kjellander, P.; Andrén, H.; Smith, H. Quantitative estimates of tree species selectivity by moose (Alces alces) in a forest landscape. Scand. J. For. Res. 2007, 22, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uthållig Älgförvatlning i Samverkan; SOU 2009:54; Fritzes Offentliga Publikationer: Stockholm, Sweden, 2009; p. 218.

- Wennberg Di Gasper, S. Natural Resource Management in an Institutional Disorder: The Development of Adaptive Co-Management Systems of Moose in Sweden; Luleå University of Technology: Luleå, Sweden, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- CBD SBSTTA. Convention on Biological Diversity: Recommendation V/10 Ecosystem approach—Further conceptual elaboration. In Proceedings of the 5th Subsidiary Body of Scientific and Technological Advice Meeting, Montreal, QC, Canada, 31 January–4 February 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Älgförvaltningen; 2009/10:239; Fritzes Offentliga Publikationer: Stockholm, Sweden; p. 84.

- Emerson, K.; Nabatchi, T. Collaborative Governance Regimes; Georgetown University Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; p. 264. [Google Scholar]

- Jager, N.W.; Newig, J.; Challies, E.; Kochskämper, E. Pathways to Implementation: Evidence on How Participation in Environmental Governance Impacts on Environmental Outcomes. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodin, Ö. Collaborative environmental governance: Achieving collective action in social-ecological systems. Science 2017, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koontz, T.M.; Jager, N.W.; Newig, J. Assessing Collaborative Conservation: A Case Survey of Output, Outcome, and Impact Measures Used in the Empirical Literature. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2019, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjölander-Lindqvist, A.; Sandström, C. Shaking Hands: Balancing Tensions in the Swedish Forested Landscape. Conserv. Soc. 2019, 17, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjärstig, T.; Sandström, C.; Lindqvist, S.; Kvastegård, E. Partnerships implementing ecosystem-based moose management in Sweden. Int. J. Biodivers. Sci. Ecosyst. Serv. Manag. 2014, 10, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dressel, S.; Ericsson, G.; Sandström, C. Mapping social-ecological systems to understand the challenges underlying wildlife management. Environ. Sci. Policy 2018, 84, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uppföljning av Mål Inom Älgförvaltningen—Redovisning av Regeringsuppdrag; Swedish Environmental Protection Agency: Stockholm, Sweden, 2018; p. 59.

- Redovisning av Regeringsuppdrag om Älgförvaltning; Swedish Environmental Protection Agency: Stockholm, Sweden, 2015; p. 21.

- Ansell, C.; Gash, A. Collaborative governance in theory and practice. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2008, 18, 543–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, S.; Guerrero Gonzalez, A.; Wyborn, C. Understanding Effectiveness in its Broader Context: Assessing Case Study Methodologies for Evaluating Collaborative Conservation Governance. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2019, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newig, J.; Challies, E.; Jager, N.W.; Kochskaemper, E.; Adzersen, A. The Environmental Performance of Participatory and Collaborative Governance: A Framework of Causal Mechanisms. Policy Stud. J. 2018, 46, 269–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biddle, J.C.; Koontz, T.M. Goal specificity: A proxy measure for improvements in environmental outcomes in collaborative governance. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 145, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. A General Framework for Analyzing Sustainability of Social-Ecological Systems. Science 2009, 325, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koontz, T.M.; Newig, J. From Planning to Implementation: Top-Down and Bottom-Up Approaches for Collaborative Watershed Management. Policy Stud. J. 2014, 42, 416–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dressel, S.; Ericsson, G.; Johansson, M.; Kalén, C.; Pfeffer, S.E.; Sandström, C. Evaluating the outcomes of collaborative wildlife governance: The role of social-ecological system context and collaboration dynamics. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 105028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dressel, S.; Johansson, M.; Ericsson, G.; Sandström, C. Perceived adaptive capacity within a multi-level governance setting: The role of bonding, bridging, and linking social capital. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 104, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahl-Wostl, C. A conceptual framework for analysing adaptive capacity and multi-level learning processes in resource governance regimes. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2009, 19, 354–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F. Environmental Governance for the Anthropocene? Social-Ecological Systems, Resilience, and Collaborative Learning. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodin, Ö.; Sandström, A.; Crona, B. Collaborative Networks for Effective Ecosystem-Based Management: A Set of Working Hypotheses. Policy Stud. J. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, K.; Nabatchi, T. Evaluating the Productivity of Collaborative Governance Regimes: A Performance Matrix. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2015, 38, 717–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newig, J.; Fritsch, O. Environmental governance: Participatory, multi-level and effective? Environ. Policy Gov. 2009, 19, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A. Environmentality: Technologies of Government and the Making of Subjects; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2005; p. 344. [Google Scholar]

- Sjölander-Lindqvist, A.; Johansson, M.; Sandström, C. Individual and collective responses to large carnivore management: The roles of trust, representation, knowledge spheres, communication and leadership. Wildl. Biol. 2015, 21, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjölander-Lindqvist, A.; Risvoll, C.; Kaarhus, R.; Lundberg, A.-K.; Sandström, C. Knowledge claims and struggles in decentralized large carnivore governance: Insights from Norway and Sweden. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conley, A.; Moote, M.A. Evaluating collaborative natural resource management. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2003, 16, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, K.; Gerlak, A.K. Adaptation in Collaborative Governance Regimes. Environ. Manag. 2014, 54, 768–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebel, L.; Anderies, J.M.; Campbell, B.; Folke, C.; Hatfield-Dodds, S.; Hughes, T.P.; Wilson, J. Governance and the Capacity to Manage Resilience in Regional Social-Ecological Systems. Ecol. Soc. 2006, 11, 19. Available online: http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol11/iss1/art19/. [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.S.; Evely, A.C.; Cundill, G.; Fazey, I.; Glass, J.; Laing, A.; Newig, J.; Parrish, B.; Prell, C.; Raymond, C.; et al. What is Social Learning? Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelling, M.; High, C. Understanding adaptation: What can social capital offer assessments of adaptive capacity? Glob. Environ. Change 2005, 15, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paldam, M. Social Capital: One or Many? Definition and Measurement. J. Econ. Surv. 2000, 14, 629–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brondizio, E.S.; Ostrom, E.; Young, O.R. Connectivity and the Governance of Multilevel Social-Ecological Systems: The Role of Social Capital. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2009, 34, 253–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nenadovic, M.; Epstein, G. The relationship of social capital and fishers’ participation in multi-level governance arrangements. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 61, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grafton, R.Q. Social capital and fisheries governance. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2005, 48, 753–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Om Jakt och Viltvård; 1991/92:9; Fritzes Offentliga Publikationer: Stockholm, Sweden, 1991; p. 274.

- Dressel, S. Social-Ecological Performance of Collaborative Wildlife Governance: The Case of Swedish Moose Management. Doctoral Thesis, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Umeå, Sweden, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Robson, C. Real World Research, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2011; p. 586. [Google Scholar]

- Good Research Practice; Swedish Research Council: Stockholm, Sweden, 2017.

- Creswell, J.W.; Miller, D.L. Determining Validity in Qualitative Inquiry. Theory Pract. 2000, 39, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma-Wallace, L.; Velarde, S.J.; Wreford, A. Adaptive governance good practice: Show me the evidence! J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 222, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaffee, S.L. Collaboration Strategies for Managing Animal Migrations: Insights from the History of Ecosystem-Based Management. Environ. Law 2011, 41, 655. [Google Scholar]

- Olsson, P.; Folke, C.; Berkes, F. Adaptive Comanagement for Building Resilience in Social–Ecological Systems. Environ. Manag. 2004, 34, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galaz, V.; Olsson, P.; Hahn, T.; Folke, C.; Svedin, U. The problem of fit among biophysical systems, environmental and resource regimes, and broader governance systems: Insights and emerging challenges. In Institutions and Environmental Change—Principal Findings, Applications, and Research Frontiers; Young, O.R., King, L.A., Schröder, H., Eds.; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008; pp. 147–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, J.R.A.; Young, J.C.; McMyn, I.A.G.; Leyshon, B.; Graham, I.M.; Walker, I.; Baxter, J.M.; Dodd, J.; Warburton, C. Evaluating adaptive co-management as conservation conflict resolution: Learning from seals and salmon. J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 160, 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stöhr, C.; Lundholm, C.; Crona, B.; Chabay, I. Stakeholder participation and sustainable fisheries: An integrative framework for assessing adaptive comanagement processes. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dressel, S.; Sjölander-Lindqvist, A.; Johansson, M.; Ericsson, G.; Sandström, C. Achieving Social and Ecological Outcomes in Collaborative Environmental Governance: Good Examples from Swedish Moose Management. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2329. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042329

Dressel S, Sjölander-Lindqvist A, Johansson M, Ericsson G, Sandström C. Achieving Social and Ecological Outcomes in Collaborative Environmental Governance: Good Examples from Swedish Moose Management. Sustainability. 2021; 13(4):2329. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042329

Chicago/Turabian StyleDressel, Sabrina, Annelie Sjölander-Lindqvist, Maria Johansson, Göran Ericsson, and Camilla Sandström. 2021. "Achieving Social and Ecological Outcomes in Collaborative Environmental Governance: Good Examples from Swedish Moose Management" Sustainability 13, no. 4: 2329. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042329

APA StyleDressel, S., Sjölander-Lindqvist, A., Johansson, M., Ericsson, G., & Sandström, C. (2021). Achieving Social and Ecological Outcomes in Collaborative Environmental Governance: Good Examples from Swedish Moose Management. Sustainability, 13(4), 2329. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042329