1. Introduction

Mechtild Rössler [

1], the Director of UNESCO, states that there are 105 properties on the World Heritage List that are categorized as cultural landscapes so far. More than half of these still have active roles in sustaining the lives of local communities, including indigenous peoples. Rural landscapes have always been a source of life and inspiration. They are a living testimony to how humans have coexisted with nature. Despite this, many rural landscapes and their connection with people are under a growing threat due to various factors including depopulation and urbanization of rural communities and intensifying natural disaster and climate change risks.

According to Antrop [

2], the historic village as a living space is constantly changing and is a reflection of the life of the population and its activities in the area. It carries its history and present, which comprise the starting point for its future. This point of view shows that the concept of sustainability of historic village communities does not necessarily mean maintaining morphologically stable village environments. The concept of community sustainability should consider the changing morphology of each rural environment. However, UNESCO localities have specific rules. As stated by Rugeiero et al. [

3], the rural buildings, local context, natural environment and also agricultural activities are in close correlation with each other [

4]. In fact, the spread of rural buildings in agricultural territory has served the function of agricultural activities and has very often provided a useful dwelling for agricultural workers in the past [

5,

6]. These kinds of rural buildings represent a considerable heritage with high historical and architectural value. They have an important part in the image of the rural landscape [

7] and this image cannot be separated from the buildings that belong to it [

8], although land use in surrounding areas has changed.

Preserving the value of these territories is therefore a primary objective. Several authors around the world have focused on the assessment and possibilities of the sustainability of UNESCO sites in various respects, including for example [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14].

The site of Vlkolínec, which was inscribed on the UNESCO World Cultural and Natural Heritage List in 1993 (hereinafter referred to as the UNESCO World Heritage Site), is a village settlement type with wooden architecture typical for mountain and foothill areas with undisturbed log houses in the middle of traditionally used land with narrow-block fields and pastures. The settlement, which was first mentioned in 1461, has remained untouched by new construction and represents a unique urban complex of original folk buildings. It was originally a settlement of loggers, shepherds and farmers. At present, it is a living settlement, as the inhabitants still use or live in the houses. This partly hampers its sustainable development, as it is necessary to combine the requirements for the protection of UNESCO World Heritage sites and the needs of their inhabitants for adequate facilities and quality of life.

The time period from year 1769 to the present represents the stage when the appearance of the studied area was radically changed. In order for assessment objective changes in the landscape, we had need to use specific research materials. For this purpose, the historical maps from archives were selected. We had available cartographic products from 1783, 1823, 1949, 2007 and 2017.

Tourism is an opportunity but also poses a threat to UNESCO World Heritage Sites. The relationships between World Heritage sites which serve not only as a tourism product and its communities which live in or around the sites have several aspects [

15]. The complexity of these relationships can determine the potential for success in promoting their interests. According to Mansfeld [

16], the main task is to find the answer to the question: How can we maintain socio-cultural sustainability in such a site and at the same time share the cultural values of this site with tourists?

According to Murphy [

17], improving livelihoods and maximizing benefits for the domestic population includes developing the appropriate use of domestic work and the domestic production of goods and services, while developing appropriate and sustainable infrastructure, support policies and environmental strategies [

14,

18]. The development of sustainable tourism must be implemented through direct involvement of and cooperation between the local people, the private sector, development policy makers, academia and local active third sector organizations [

19].

Any form of tourism affects the indigenous population and the destination itself. According to Sabolová [

20], these effects can be perceived both positively and negatively. Scientific works from the 1960s, which focused on the impact of tourism, mainly considered the economic factors and positive impact of tourism. Later, the consequences of tourism began to be perceived more critically, mainly by anthropologists and sociologists who emphasized negative socio-cultural influences [

21]. During the 1980s and 1990s, the view of the impacts and consequences of tourism became more balanced [

22,

23] and both positive and negative influences were discussed, especially due to the idea of sustainable tourism [

20].

As [

24] point out in their study of the rural landscape, for its evaluation of the rural landscape, UNESCO places high values on the following parameters: historical features, traditional crops and local products, sustainability of land use and the presence of agricultural architecture.

Our paper provides an overview of the territorial development of an area with very specific protection and management. We recorded information about the landscape characteristics that disappear in the study area. It is necessary to archive information about landscape elements and social processes that have been implemented over the centuries in this attractive area.

The aim of the paper is to analyze the potential and the development of the UNESCO site in Vlkolínec according to maps, different forms of literature and other information sources, to present the changes in the structure of cultural landscape in the area based on available older photographs, historical maps and aerial photographs. It aims to identify landscape structures and propose a strategy for sustainable tourism development at the Vlkolínec that preserves its cultural, natural and landscape values.

2. Materials and Methods

We prepared the delimitation of the territory and the development of the settlement of the UNESCO site of Vlkolínec according to the available sources, from data provided by the staff of the Municipal Office in Ružomberok and data obtained from the Regional Administration of the Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic.

The historical landscape structure was interpreted in two time horizons, namely in 1783 and 1823. The use of the landscape in 1783 was processed using the documents of the First and Second Austro-Hungarian military mapping at a scale of 1:28,800. With the precision of their design as well as their content, the maps produced by this mapping meet the strict scientific research criteria necessary for their correct interpretation and evaluation for basic and applied research, especially historical, geographical and landscape-ecological research. They provide information on the relevant categories of land use represented mainly by land use forms such as arable land, permanent grassland, forest areas and built-up areas of a residential, productive or transport nature. The year 1949 was evaluated on the basis of archival military panchromatic aerial photographs at a scale of 1:15,000. Land use in the years 2007 and 2017 was interpreted using orthophotos at a scale of 1:5000 from 2007 and 2017 (Orthophotomap © Geodis Slovakia, s.r.o., 2003; Aerial photography and digital orthophotomap © Eurosense s.r.o. 2007, 2017), which were verified by field survey. The landscape structure maps were created in the environment of the “ArcGIS 9.2 software” geographic information systems. For the periods of 1949, 2007 and 2017, we interpreted the overall change in landscape use, as well as trends in the types of landscape use change according to the works of [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39], etc. When interpreting the historical state of use, we used old historical photographs, paintings as well as written documentation. The current state of land use was verified by field research. The basic information was obtained through consultation with the employees of the Municipal Office in Ružomberok, to which Vlkolínec belongs.

During the summer tourist season of 2017, we conducted a sociological survey directly at the site using guided interviews with homeowners (permanent residents and holiday cottage owners) and stakeholders. The interviews were focused on identifying problems and proposing solutions so as to avoid disturbing the uniqueness of this site, but at the same time to also attract tourists. Based on the results of the survey, we evaluated the identified phenomena, structures and values and compared them with the desired state of the landmark protection and the degree of sustainability. Overall, we managed to process 55 questionnaires (a number which is three times larger than the population). Data collection took place in the period from March to May of 2017. The respondents included 30 women (54%) and 25 men (46%), while the average age of the respondents was 42.5 years. The questionnaire contained 9 questions (open answers) focused on the current state and the future of the Vlkolínec site, and multiple answers were possible. The questionnaire also included information about the gender, age and education of the respondents.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the UNESCO Site Vlkolínec

The UNESCO site Vlkolínec is located in the northern part of Slovakia and administratively belongs to the town of Ružomberok (

Figure 1). Vlkolínec was established at the turn of the 14th and 15th centuries and its inhabitants made their living through agriculture, breeding of cattle and sheep, logging, beekeeping and the production of shingles [

40]. The historical character of the Vlkolínec settlement with unchanged wooden log houses has been preserved mainly due to its isolated location in the Veľká Fatra mountains at an altitude of 718 m above sea level at the southern foot of the Sidorovo hill (1099 m above sea level), which is the dominant feature of the area (

Figure 2). Its traditional folk architecture and natural environment with narrow strips of fields, wide meadows and pastures gave it a rare and unique but fragile genius loci. As a result of social changes, these traditional forms of farming gradually began to disappear from the landscape in the 1950s, and many disappeared altogether. As a result, the characteristic appearance of the Vlkolínec protection zone changed.

In 1977, the Vlkolínec site was declared a Folk Architecture Monument Reserve (FAMR) under the national legislation and its area was 4.9 ha. At present, Vlkolínec forms an administrative part of the town of Ružomberok in central Slovakia. It does not have a dedicated cadastral area; the information on the area refers to the designated Folk Architecture Monument Reserve of Vlkolínec with an area of 4.9 ha. It was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in December 1993 in Cartagena based on criteria 4 and 5. The fourth criterion includes unique examples of building types, architectural and technical groupings or landscapes which document a significant degree of human history. The fifth criterion includes unique examples of traditional settlement and land use which represents a given culture, or the interaction of human activity and the environment, especially when that landscape is vulnerable to the effects of irreversible change.

The settlement of the Vlkolínec area began in the period of the second half of the 14th and the first half of the 15th century [

40]. In 1461, it became a serf settlement of the town of Ružomberok. As a settlement belonging to the area of the town of Ružomberok, Vlkolínec was a part of the Likava Castle estate. This status lasted until the middle of the 20th century. After the Second World War, the inhabitants of Vlkolínec requested adequate living conditions, comparable to other local parts of the city. This brought up a proposal for the locals were to be relocated to Ružomberok, which was, however, not carried out. At present, Vlkolínec is treated as a part of Ružomberok.

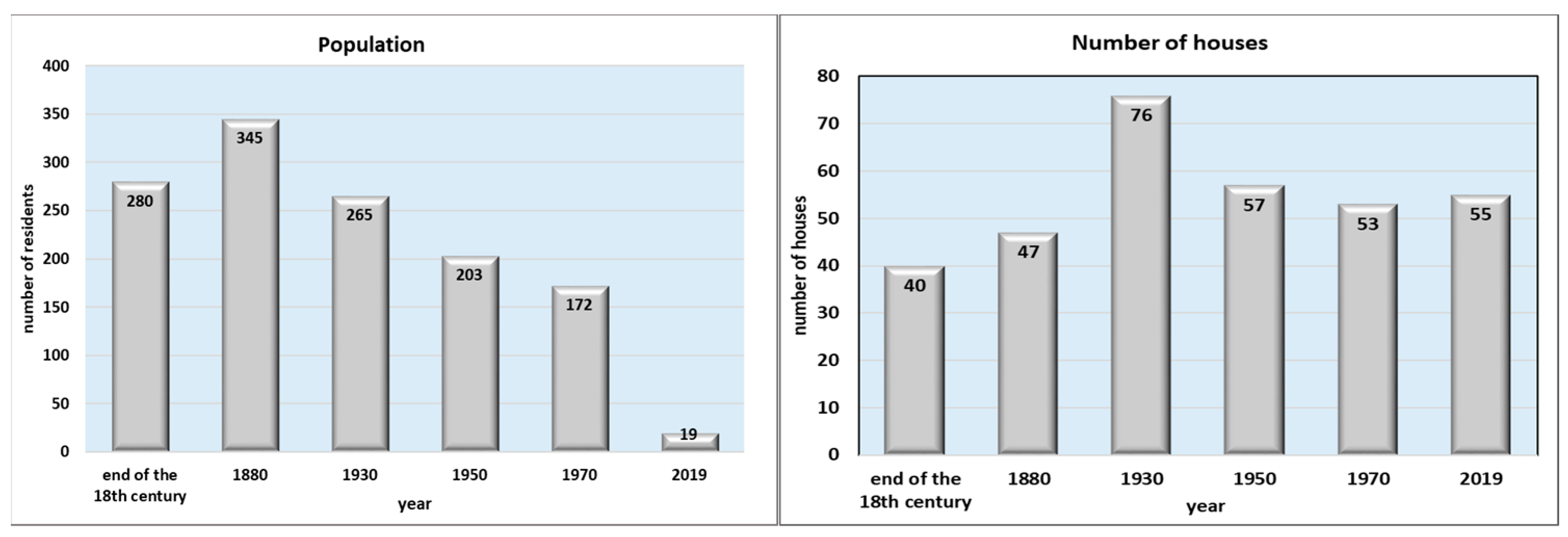

The development of the population can be followed only on the basis of historical sources; according to these historical sources, a total of 117 people lived at Vlkolínec in 1766, which grew to 334 in 1825. In 1869, Vlkolínec had its largest population of 345 inhabitants (

Figure 3). Subsequently the population decreased to 265 in 1935, 203 in 1950 and only 172 in 1971 [

40,

41]. At present, only 19 people live at Vlkolínec. A similar trend can be found when we look at the development of the number of houses. At the end of the 16th century, there were about 5 houses at Vlkolínec, with 4 settlements (

sessia) and 5 houses owned by five peasants (serfs). At the end of the 18th century there were 40 houses and in 1880 there was a total of 47 houses. In 1930 there were 76 houses and the maximum number was reached in 1935 when there were 82 houses. At this point of time, house numbers were assigned for the first time. In 1944, during the Slovak National Uprising, 13 houses burned down. At present, there are 55 houses at Vlkolínec (of which only 6 are permanently inhabited by 19 inhabitants) and 2 of them are brick houses [

42].

3.2. Historical Landscape Structures of the Vlkolínec Locality

Historical landscape structures represent the set of elements and phenomena in the landscape which arose from the deliberate activity of humans during history until the recent past. Such activity was transformed the nature or created new, still preserved structures [

43,

44,

45,

46]. The Vlkolínec locality presents a preserved form of the historical mountain archetype of the landscape [

47]. These are specific, time-bound and spatially constantly decreasing landscape structures. They are a relic of anthropic activities that have survived to the present day.

Two types of historical landscape structures are characteristic of Vlkolínec: architectural and agricultural.

3.2.1. Architectural Historical Structures

Vlkolínec is a lump village type with two-row alleys and long yards. Near the middle of the village, the street splits into two mutually perpendicular roads. The settlement axis of the village is formed by a stream flowing from the slopes of Sidorovo. The distribution of stream water is conducted through dug wooden gutters. Wooden log buildings are oriented with the gable facing the street, while long narrow yards are common for several residential houses built one behind the other or opposite each other. The yards are mostly open, though some of them are closed by slab gates with a characteristic shingled roof [

40].

Log haybarns are located on higher meadows around Vlkolínec. It is estimated that at the time of the greatest development of the village, there were about 60 of them in its vicinity [

48]. At present, the haybarns no longer fulfil their function, many have already disappeared and those that have been preserved are in poor technical condition. Since 2008, they have been filled with hay from mown meadows, which are used for winter feeding of forest animals (

Figure 4).

In addition to residential houses and farm buildings, part of the development also includes secular, religious and civic buildings: a wooden winch well from 1770 that is 12 m deep which served as the only source of drinking water in the village; the log bell tower has log sides lined on the outside with split shingles and a cross is placed on the top of the shingled roof. It was the only timepiece in the settlement and served to announce prayers. These buildings also include the brick building of the former burgher school—today it is a gallery and also contains the Church of the Visitation of the Blessed Virgin Mary from 1875 together with a local cemetery.

3.2.2. Agricultural Historical Structures Are Represented by Several Types at Vlkolínec

The Vlkolínec settlement and its surroundings are characteristic of the following types of agricultural elements of rural landscapes in the Liptov region:

gardens located in the immediate vicinity of the dwellings, behind the farm buildings,

a complex of terraced terrain with meadows divided by vegetation in parallel lines; this is a consequence of maintained alternating farming, expresses primary land use and is therefore considered as one of the most valuable elements (

Figure 5),

a homogeneous set of meadows and pastures, where boundaries were removed in the 1970s in order to merge the agricultural land.

At present, the original fields, which were traditionally worked by hoeing and plowing, have become practically non-existent. These were mostly converted into meadow-pasture vegetation. In the 1970s, the borders were also removed, and the merging created a uniform large set of meadows and pastures. The terraced arrangement of the terrain with meadows divided by linear and group shrubs and in some places by tree vegetation in parallel lines was preserved only in the western and north-western part. Few people live in the settlement and they are not engaged in the breeding of farm animals. With the disappearance of agricultural activity, successive processes are gradually taking place on the meadows and pastures.

3.3. Changes in Landscape Structure on Historical Maps and Aerial Photographs

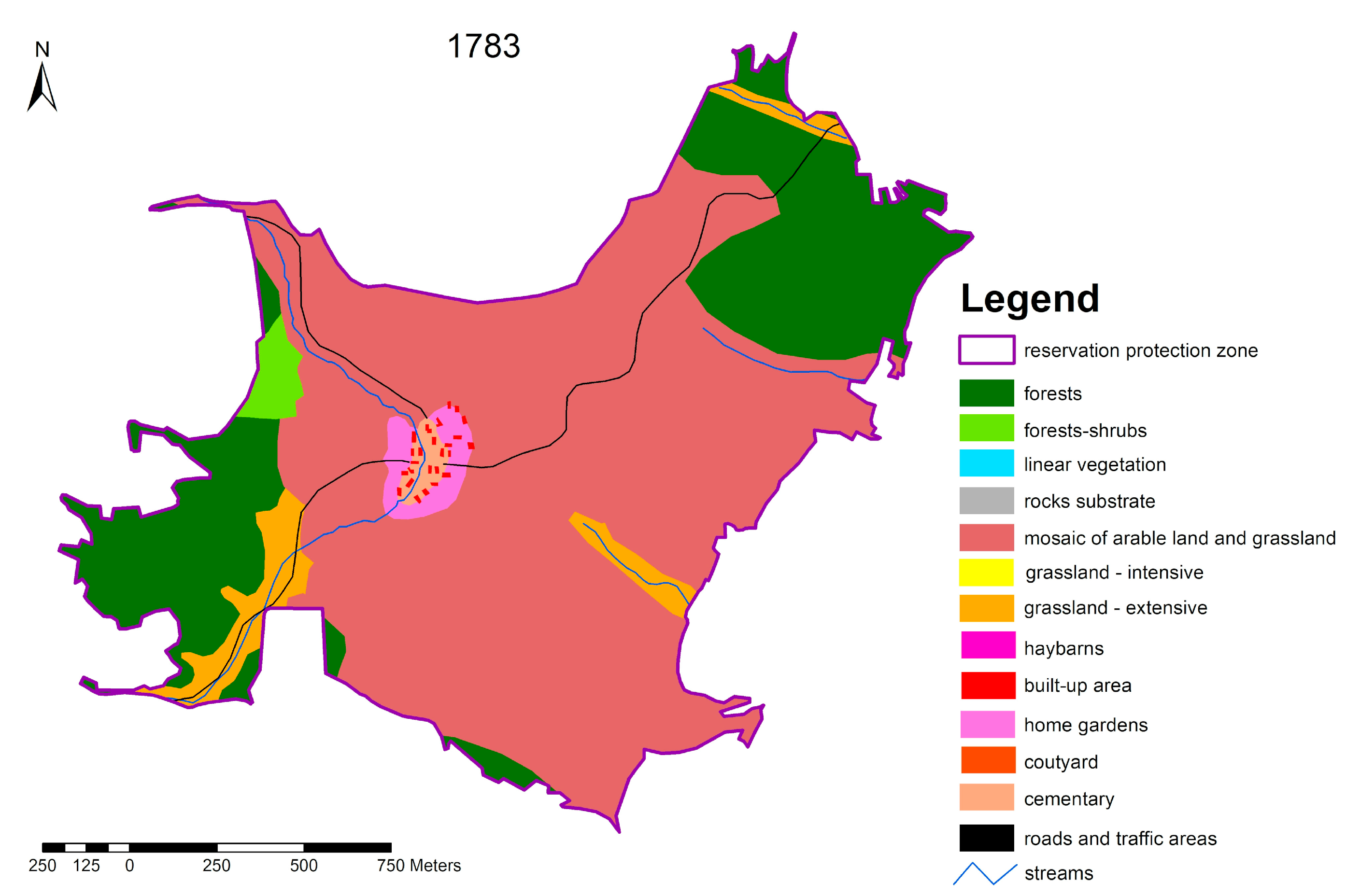

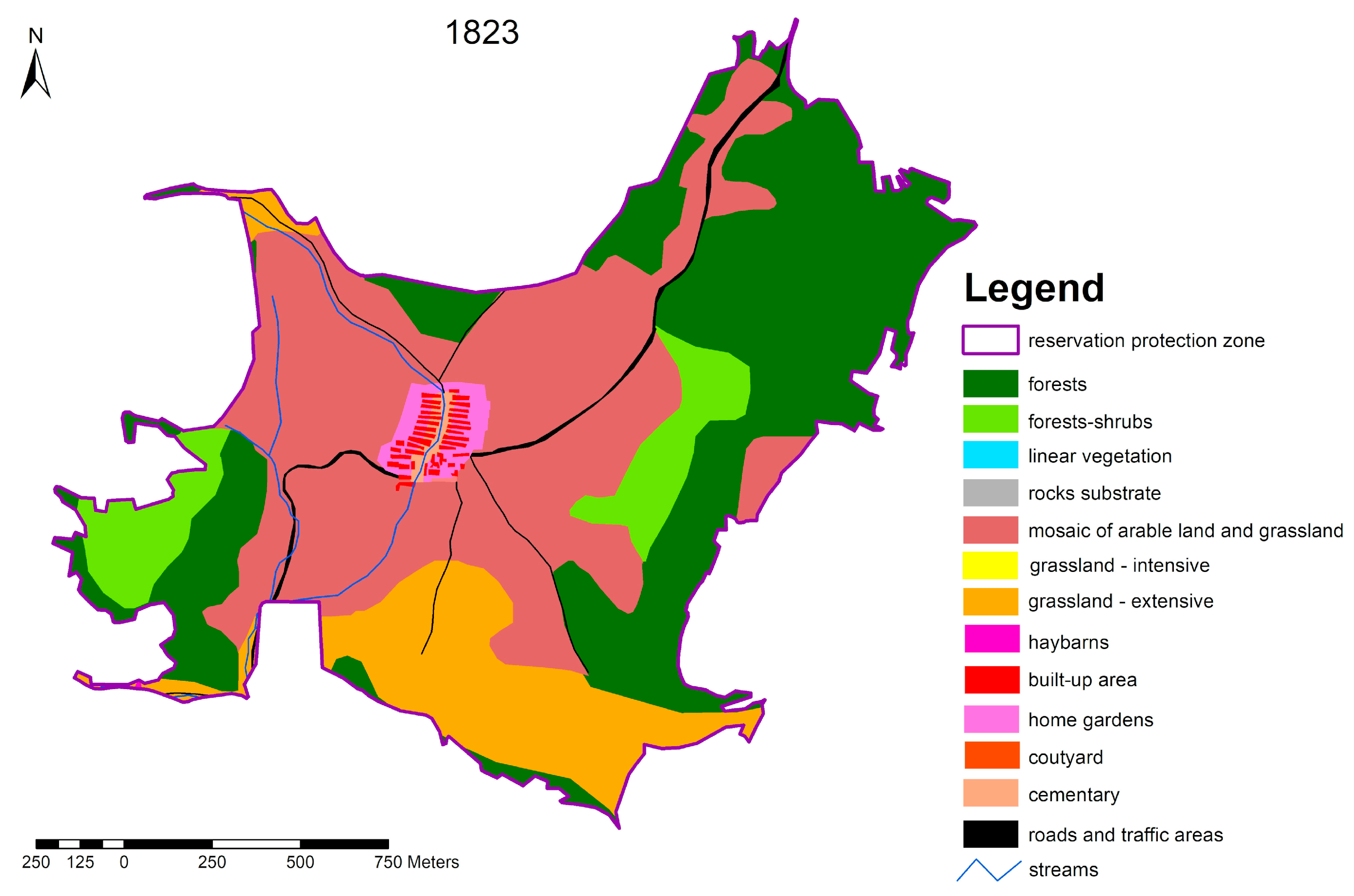

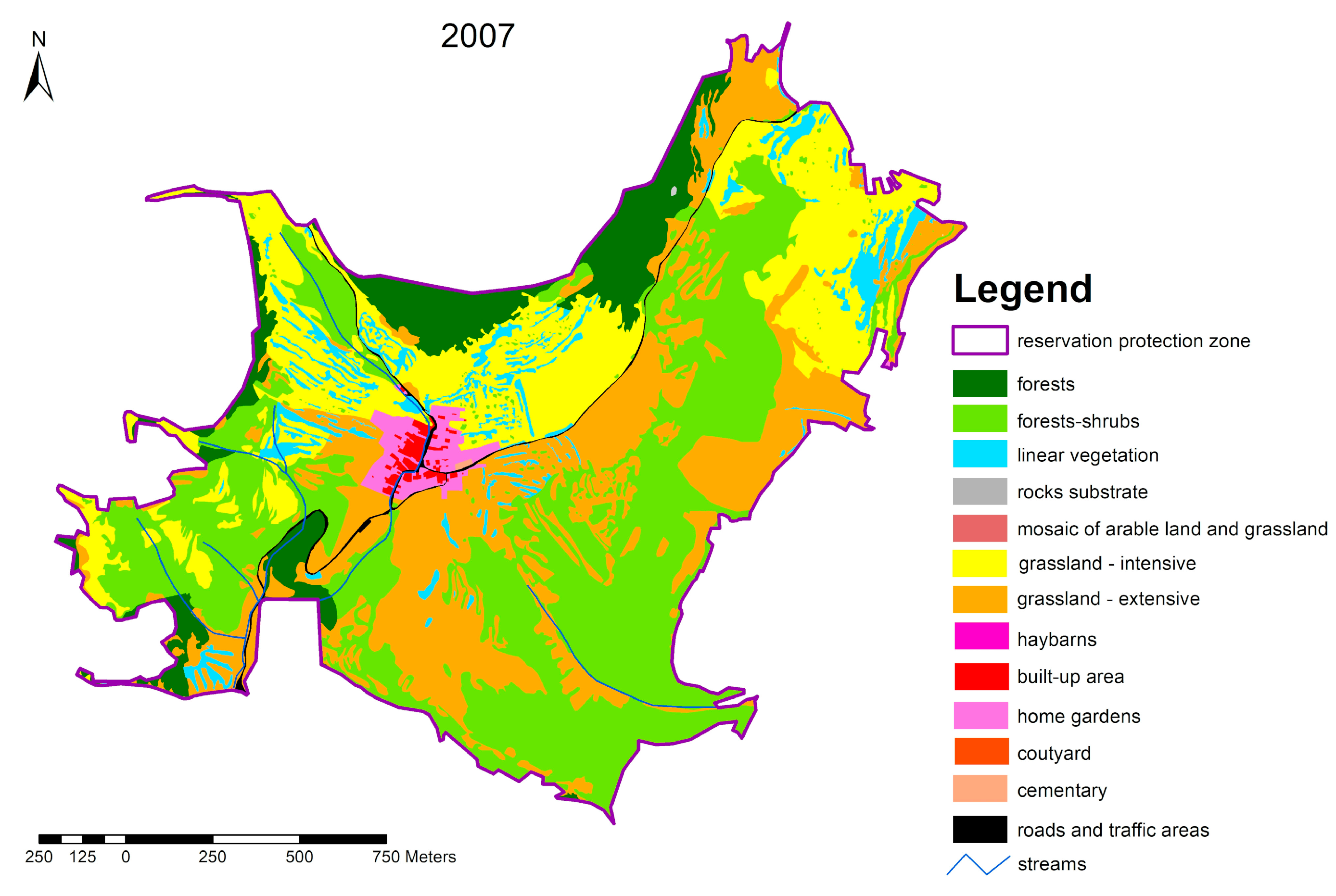

To assess the development of the secondary landscape structure of the Vlkolínec protection zone, we focused on the identification of landscape elements in the background materials (historical maps, aerial photographs) in the years of 1783, 1823, 1949, 2007 and 2017 (

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10,

Table 1). We wanted to visualize the development of the intensity of land use (especially the intensification of agriculture and the abandonment of mosaics), which may negatively affect the preservation of the main goal of the UNESCO World Heritage Site. In total, we interpreted 13 landscape elements, focusing on historical landscape structures. For these elements, we focused on identifying their area and percentage in the landscape in relation to their changes during the period under review.

3.3.1. Landscape Structure in 1783

The structure of the Vlkolínec landscape in the second half of the 18th century (1783) confirms the extensive agricultural focus which was influenced by morphometric and climatic conditions (

Figure 6). More than 2/3 of the area in this period were formed by various forms of mosaic of arable land and grassland. Their location was influenced by the morphometric characteristics of the area and accessibility from the settlement. These mosaics were directly connected to the family gardens and surrounded the settlement from all sides. At their edges around watercourses, we have identified compact extensive grasslands making up almost 5% of the area. More intensive use of them was probably hindered by periodic water logging. The second largest landscape element is formed by the forest stands. They make up more than 25% of the territory, mainly in the NE part below the Sidorovo hill and the SW part around the Laštek hill. In addition to built-up areas (0.26%) and house gardens (1.53%), we also included a landscape element of courtyards (0.65%). These formed an area in the middle of the settlement, which was used centrally, and it was not possible to identify a road within it. Roads were only identified only as lines connecting the settlement with the surrounding areas.

3.3.2. Landscape Structure in 1823

In the first half of the 19th century (1823), the character of the area began to change (

Figure 7). The morphometric parameters represented on the main influence for the decrease of arable land in mosaics with permanent grassland (almost 40% of the area). This decrease occurred to the benefit of grasslands in the southern part of the territory, the share of which increased to almost 14%, with an increase in the share of forest stands in the eastern part. Forest stands accounted for 35% of the area. In this period, we identified a relatively high proportion of forest cover (7.5%) in the former mosaics in the NW part of the territory. In addition to built-up areas, house gardens, yards and cemeteries, we also managed to identify haybarns. The occurrence of these farm buildings is related to the growth of compact grasslands in the area and the need for seasonal hay storage.

3.3.3. Landscape Structure in 1949

More than a hundred years later (1949), a significant difference in land use can already be seen (

Figure 8). The changes occurred mainly in the decline or extinction of forest stands (only 0.05%) and forest cover (5.23%), which were preserved, mainly in the vicinity of watercourses. Forest stands were transformed mainly into extensive grasslands. Grasslands made up 33% of the territory, and we have identified linear woody vegetation (7.27%) primarily in the vicinity of roads. The area had become significantly transformed into agricultural area. More than 50% of the area consisted of mosaics of arable land and permanent grassland. There was also a slight decrease of the built-up area—this was caused by the destruction (burned down) of several buildings during World War II.

3.3.4. Landscape Structure in 2007

In 2007, socialist collectivization was reflected in the area (

Figure 9). For the whole area, except for home gardens, arable land had almost completely disappeared. The mosaics became completely extinct. The landscape was extensifying. Marginal slope-exposed positions in the northern part were transformed into forest stands (almost 9%). In the southern, SE and NW parts, there was an intensive increase in forest cover (35%) which caused a compact overgrowth of grasslands. Forest stands were planted in degraded parts of exposed localities, in places of former pastures. The original mosaics are transformed into extensive permanent grasslands (10.7%) with linear vegetation (10.3%). North of the urban area and in the NE part of the territory, large-scale intensive grasslands were covering an area of more than 31%. Overall, the area was beginning to transform into a forest-agricultural landscape.

3.3.5. Landscape Structure in 2017

The use of land in 2017 was very similar to 2007. With the adjustment of extensive stands and the extinction of some linear stands, we could see an increase in large-scale intensive grasslands to 34% (

Figure 10). A similar trend (slight increase) could also be observed in forest stands and forest shrubs—some of the internal grasslands were being overgrown. In the area, we still managed to identify historical buildings such ashaybarns as the relics of the original cultural landscape.

3.4. Sociological Research

A total of 55 respondents (local stakeholders: permanent residents, cottagers, farmers, foresters) took part in the questionnaire survey, which involved 9 basic questions (open answers). Stakeholders clearly expressed that the main value of Vlkolínec is in the preservation of traditional architecture in the natural environment of the original cultural mountain agricultural landscape. All answers or options represented this view. Rural architecture with nature and environment were included in up to 63.5% of responses. When asked about the most valued features, it is also interesting to see the respondents saw Vlkolínec as a whole entity with peace and quiet but also noted a genius loci.

When considering the missing things in that location, it could be observed that the responses mentioning these things were “local” people. Among all the options, the lack of a shop and failure to improve the quality of roads ranked on the top place (39.1% of responses). At the same time, there is an effort to improve the situation for visitors and tourists, as the other options in the responses included the improvement or creation of services (mainly catering facilities) and subsequent construction of public toilets.

When asked about the outlook on what will happen in 20 years, the majority was in favor of better and original uses of the landscape in the context of not allowing the construction of new buildings in non-original architecture (21%). Furthermore, there is an effort to preserve the permanent population (16.1%), followed by expectations of the improvement of the condition of roads (14.5%). It could be said that all the responses, except for the one concerning the construction of the guest-house, are aimed at keeping Vlkolínec alive with permanent residents. At the same time, it is clear that the responses of the respondents are somewhat divided. While the holiday cottage owners would prefer the development of tourist infrastructure not directly in Vlkolínec—making up 38.5% of responses, the permanent residents would support development directly in Vlkolínec—making up 36.5% of respondents. However, the main problem seems to be the insufficient quality of transport roads (46.2% of responses). This confirms the absence of basic infrastructure in the area and the need of permanent residents to have it as close as possible. This was also true for the function of farm buildings. Approximately the same number of responses was in favor of the conversion of these buildings into housing (33.3%) and in favor of their preservation for farming purposes (32.4% of respondents).

For the question on where they would like to spend their free time, answers were prepared, which we selected on the basis of previous research. The questionnaires were applied for people who were directly interested in the existence of Vlkolínec as a locality with a major cultural and historical value. Almost half of the answers—39.1%—imagine their wooden house or their backyard with the garden as a good location to spend their free time in. However, the genius loci were also represented by the inhabitants of this rural site. As the landscape has pleasant aesthetics, up to 32.2% of responses mentioned spending their free time pleasantly in the surroundings and nature around Vlkolínec.

In terms of revitalization measures, respondents would support activities, preferably in the area of growing fruits, vegetables and other agricultural products, (16.7%) in the area of beekeeping development (12.1%) and in the area of livestock breeding (10.6%).

The reactions to the changes in the area over the last 10 years were quite interesting. We observed harmony between the holiday cottage owners and the locals. They all see the benefits in a higher number of cultural events, the improvement of the infrastructure for tourists (41.1%) and at the same time, the direct improvement of the situation in the municipality concerning the functioning of the civic association and fire protection (35.2%). On the other hand, a clear deterioration is perceived with regards to the reduction of the quality of transport infrastructure (28%), the reduction or non-use of landscape (14%) and the consequent negative impact of misbehaving tourists who do not respect the privacy of residents and holiday cottagers’ owners (a total of 24%). It was interesting to see several responses pointing to the negative experiences with forest animals damaging the property in gardens and the need for measures to protect them (as the responses mainly mentioned bears, this would also apply to beekeeping).

4. Discussion

Many destinations seek the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization’s (UNESCO) World Heritage status, as it has the potential to attract large tourist numbers. Hall and Piggin [

49] find in their study (46 sites) that over two thirds of the World Heritage Sites (WHSs) in their study (46 sites) recorded an increase in visitor numbers after gaining WHS status. Thus, the UNESCO label frequently functions as a destination brand [

50]. The designation of WHSs by UNESCO strengthens the international and national image of heritage destinations in the growing market of cultural tourism [

51].

Our results were confirmed by Gullino and Larcher [

24] and Gullino et al [

52]. In the 14 rural World Heritage Sites, they confirmed that integrity of landscape is a value of both cultural and natural landscapes and that it is the key to site identity. They demonstrated that UNESCO assigns a high value to the following parameters: historical features, traditional crops and local products, land-use and agricultural practice permanence and the presence of architecture related to agricultural activity. They found the relationship between culture and nature to best characterize the integrity of a rural landscape, rather than a natural or cultural landscape alone. The importance of the site is in its cultural and historical value. Vlkolínec already serves as a rural Ecomuseum (acting as a central attraction housing remarkable folk-life collections acting as central attraction housing remarkable folk-life collections). This is one of the goals that sites around the world are trying to achieve [

53].

In other countries, the value of the country is closely linked to the quality of the original rural landscape. These landscapes—that today still represent an element of strong characterization of single territorial realities—are those which denote a balanced intervention of humanity on the natural elements; they are landscapes that offer a clear presence of historical signs and legible links between structure and land use [

54]. Historical processes and the spatial level of biodiversity must be properly assessed, recognized and included in conservation strategies [

55]. Heritage is created for the purpose of current needs. To protect local agriculture from global competition, multi-functionality of agriculture was conceived and preservation of traditional rural landscapes was seen as a function of agriculture. When tourists visit destinations to appreciate the traditional agricultural landscape and/or experience traditional farming practices, they are agro-tourists as well as heritage tourists [

56]. According to [

57] ‘biocultural heritage’ recognizes not only ‘the inextricable relationship between nature and culture’ but also the importance of intangible features like ‘beliefs, values and practices of local people’. ‘Biocultural heritage’ comprises memory, experience, local knowledge and practices, associated ecosystems and biological resources [

58]. The goal of conserving traditional structures in a historic city is subject to continuous compromise and adaptation [

59]. The beauty is the characteristic of many system landscapes, including of the urban landscape and of the agrarian landscape. The “Hybrid Landscapes” represent the work of the human beings and the work of natural systems [

60].

The European Landscape Convention (ELC) may have a positive effect on such areas. Each European country has implemented the ELC differently based on its system of government and its traditions in landscape planning. Nonetheless, the impact of the ELC on various countries shows that the existence of a variety of approaches among the countries also occurs among the regions and municipalities of a single country [

61,

62,

63,

64,

65]. In Slovakia, local governments do not yet make real use of this potential. Local administration, which is usually in charge of world heritage city management, therefore should promote new management approaches such as a process-oriented approach which is sufficiently flexible, adaptive and responsive to fulfil the aforementioned requirements [

66]. Heritage sites are vulnerable to damage due to social, anthropological and environmental factors. In the case of weak management by local governments, there may be a degradation of the visual character, e.g., overgrown with invasive plants [

67]. Interpretation of remote sensing data is a suitable method for monitoring these changes in UNESCO localities. Earth Observation data, owing to its non-contact, cost effective, synoptic view and high repeatability properties, has a significant role to play in the estimation of land use changes [

68,

69,

70,

71,

72,

73,

74].

In order to understand the challenges and potential of the local/traditional use of knowledge tourism, firstly, the overall situation of securing and using the intangible cultural heritage also requires public participation. In line with [

75], which addressed this issue in Austria, we conducted a stakeholder survey of their views on tourism. They presented the gentrification of the territory and the loss of trade for the population as the main problems. This has also been confirmed in Spain [

76]. Another important factor is the equipment of the services of these sites, with a focus on the whole family [

77].

4.1. How Has the Vlkolínec Site Changed by Its Inscription on the UNESCO World Heritage List?

The inscription on the UNESCO World Heritage List brought many positives for the Vlkolínec site, but also many negatives and risks. These negatives include, in particular, a dramatic increase in the number of tourists who significantly disrupt the quality of everyday life of local people through the loss of their privacy.

Although there are no official figures on the attendance, they can be estimated on the basis of the entrance fees to the exhibition [

42]. We can conclude that attendance at Vlkolínec has been increasing for several years (except in 2015, during which the access road in the village of Biely Potok was reconstructed), and exceeded the number of 60,000 visitors.

Following the inscription on the UNESCO World Heritage List, the requirements for property owners have increased in relation to the way the maintenance work is done on their properties, the material used, the preservation of the historic color of houses, the method of fencing, etc. The loss of privacy of the indigenous people seems very negative due to the fact that many visitors do not respect the privacy of property owners. After paying the entrance fee when entering the village, they think they have the right to move around everywhere within the village like in an open-air museum.

This is also one of the reasons why the number of permanent residents is declining, with the current number only reaching 19. Gradually, homeowners who do not have a deeper personal relationship with the place are changing. Most houses are used as weekend housing or holiday cottages. Vlkolínec is thus losing a rare source of its uniqueness as a living village—its inhabitants. While log cabins and other cultural monuments in the Vlkolínec site are relatively well maintained and their condition is regularly monitored by the staff of the Regional Monuments Office in Žilina, farm buildings are falling into disrepair because the local inhabitants and cottage owners no longer keep cattle and do not use these buildings. Vehicles of both locals and tourists park chaotically in the site, souvenir and refreshments shops are aesthetically and architecturally unsuitable and the level of services offered is very low. At present, only a small number of local inhabitants are involved in providing a small number of services for the visitors and in organizing cultural and social events. These activities are provided primarily by the members of the Civic Association (OZ) Vlkolínec, which was founded in 2001. OZ Vlkolínec has signed a mandate agreement with the town of Ružomberok to ensure the collection of entry fees related to entry into Vlkolínec. These fees are used by OZ Vlkolínec to ensure services are provided for visitors to Vlkolínec, for organizing cultural and social events and for restoration and maintenance of monuments and sights at Vlkolínec.

The vulnerability of the surrounding natural environment due to the irreversible change in the lifestyle of its inhabitants is a particular issue. The land is no longer cultivated, so the fields and pastures are gradually overgrown with shrubs and trees, especially hazelnuts, rose hips, hawthorn and blackthorns. The typical terraced arrangement of the terrain has been only preserved in selected parts of the protection zone. According to [

78], this is a process that most likely cannot be reversed, only slowed down. The advancing secondary succession is clearly documented in the article by [

79] using the examples of a comparison of photographs from the state of Vlkolínec site in 1950, when most of the surrounding Vlkolínec landscape was farmed in the traditional way, with the current state (2020).

Although the return of the surrounding landscape to the “original” state of the landscape structure (e.g., to the state in the 1950s) is no longer possible, the town of Ružomberok has the ambition to preserve landscape structures thar are typical for the traditional forms of farming in the foothills in some selected parts of the Vlkolínec protection zone. In cooperation with the Agricultural Cooperative (PD) Ludrová, the Civic Association (OZ) Vlkolínec, Mestské lesy (Urban forestry) s.r.o. Ružomberok, the Catholic University of Ružomberok and other partners, the town administration is preparing proposals of revitalization plans for the restoration of traditional forms of farming in those parts which are accessible and where the remains of terraced fields are still preserved. The restoration of traditional forms of farming on selected fields should be gradually implemented in the next 10 to 15 years. The objective is to contribute to the reconstruction of characteristic landscape elements and historical landscape structures that were typical of Vlkolínec and its surroundings.

4.2. How to Keep a UNESCO Site Available for Further Generations?

Based on previous analyses, we can recommend the following proposals for preserving the site for future generations [

80]:

Completion of the transport infrastructure, i.e., construction of parking areas with service infrastructure (cafeteria, toilets, etc.), repair of the access road and local roads, improving the accessibility of the site by public transport, connection of the site with Skipark Ružomberok, construction of educational trails and increasing their attractiveness, construction of cycle paths and tourist routes or improvement of current ones.

Completion of infrastructure for sustainable tourism needs, in particular the construction of a larger number of catering facilities with year-round operation, construction of a sufficient number of public toilets, construction of an area for cultural and artistic activities (amphitheater/roofed podium), construction of entertainment and sports facilities for children (multifunctional playground), providing access to more buildings for visitors (so far this includes only 1 house and one granary), which would limit the movement of visitors in private premises of homeowners, restoration of farm buildings, haybarns, seeking opportunities to obtain subsidies for the restoration of monuments, organizing cultural events to present the development of folk crafts and the provision of internet connections.

Support of individual tourism and its soft forms (agrotourism, ecotourism), development of adventure tourism, intensification of cooperation with schools on school trips, schools in nature and increases in schooling demands throughout the year, increasing the number of activities in winter (e.g., offering multi-capacity accommodation for the organization of smaller conferences, corporate meetings, team buildings, etc.), cooperation with neighboring municipalities in providing services, the possibility of cottage holidays in adjacent valleys (Trlenská, Šepková, Dierová), attendance regulation—in terms of preserving and respecting the privacy of domestic residents—e.g., restriction of the free movement of visitors through information boards and the marking of private property.

Application of procedural measures creation of a job position—manager of the Vlkolínec destination—to coordinate the activities of the center, operatively resolve any issues, communicate with the public in order to build the Vlkolínec brand, provide marketing, etc., the need to work with the local population in order to find the optimal method of coexistence with visitors and tourists, reduction of the number of illegal accommodation providers and improvements of the regulations of visitors (determination of a tolerable number of visitors of the site), legalization of private accommodation, development of information and communication technologies and possibilities of online communication in product promotion and distribution, creation of local products and memorabilia—production and sale of local agricultural products grown or produced in the fields of Vlkolínec (e.g., flour and pastry products, honey and bee products, dried fruit, cheese, bryndza and other dairy products, distilleries, etc.) or creative workshops—organizing courses in bobbin-making, carpet weaving and creating fields on the land belonging to the town, on which the traditional way of farming for this region will be restored.

Preservation of terraced fields restoration of field roads—it is necessary to check the condition of the access roads to the fields and to propose measures to make them passable, remove overgrowth trees, develop a farming method, restore orchards and design a way to protect crops.

5. Conclusions

We assign a certain consequence status to the action of the human community, often without examining its causality. We can ask ourselves to what extent do the changes in society’s behavior affect the changes in the environment of unique spaces. The way humans use the landscape is partly dependent on natural conditions, but is also partly autonomous. The most valuable element of the landscape is its evolutionary synergetic feature in the form of the organization of the spatial-temporal rhythm of the landscape’s elements in space and time. We have an effective means in our hands for the protection of the landscape of Vlkolínec—the management of human activities. Each of the human transformations of the landscape must be seen in the context of socio-economic events that have taken place over a period of time in the past. Understanding the changes in land use completes the image of the society and its requirements for the landscape in the long term and only on that basis can we correctly interpret landscape changes and the respective causes. We can subsequently use the knowledge for the further sustainable development of the unique preserved landscape of Vlkolínec. The number of inhabitants using this area significantly affects its use. Social establishment, various types of ownership relations as well as the mutual relations in this social group of the population of Vlkolínec determine the quality of landscape use.

Our research had certain limitations due to the availability of information sources (cartographic products, demographic data, photographs of the landscape), especially from the past. Research reserves are also used in sociological research. In the beginning, the problem was for the locals to show a willingness to work with us. At the same time, some different needs of permanent residents and their requirements for quality of life were found compared to for cottagers or tourists.

Analyses of the changes in the Vlkolínec landscape and its map expression, as well as statistical analyses document a significant dependence on changes of the individual elements, especially on the socio-economic as well as legislative changes (being declared as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, nature protection, declaration of the NP Veľká Fatra, etc.) and last but not least the influence of natural factors—e.g., natural succession, erosion processes on the slope of Sidorovo, etc.

Vlkolínec was inscribed on the UNESCO World Cultural and Natural Heritage List as a remarkably intact preserved complex, which consists of typical log buildings of a characteristic Central European type. The settlement is one of the popular tourist destinations for domestic and foreign tourists. Visitors perceive this unique landscape complex as a balanced urban composition in harmony with the surrounding nature.

To this day, the settlement has not become a museum, but is a living village, as residents still use a number of the buildings. However, with the number of tourists growing more intense, the conflict between the needs of residents and homeowners and the pressure of tourism is sensed. This makes its sustainable development difficult, as it is essential to combine the requirements for the protection of UNESCO World Heritage sites with the needs of the inhabitants. The aim is that the activities of both of the parties lead to sustainable development and that the development of tourism is consistent with the preservation of the privacy of residents and homeowners.

Appropriate localization of activities in the landscape prevents future problems of use or non-use. When proposing sustainable use, it is necessary to analyze the development of landscape use in more depth. In this way we can determine the suitability of individual types of landscape ecological complex for use and this will bring us closer to long-term development trends in the landscape. Identification of areas with a different intensity of change in the observed period of 200–300 years in terms of landscape use is an auxiliary tool for economic operators in locating existing and planning new activities in the landscape (landscape ecological plans, land use plans, forest management plans).

However, it is also necessary to preserve the exterior of the settlement, terrace fields and the overall character of the cultural landscape that surrounds it. However, this collides with the current generation, which is not interested in land as such, so the preservation of this landscape is largely in the hands of civic associations and volunteers.

We focused the questionnaire survey on direct users of the area of Vlkolínec and its surroundings. We tried to collect the respondents’ personal views of the current state as well as perspectives for the future from the respondents. Due to the current socio-economic situation (low to almost no numbers of permanent residents) and unfavorable natural conditions for agriculture in the area, there is abandonment of the landscape, as well as intensive overgrowth with shrubs and trees. Without the willingness of local agricultural entities and the Municipal Office in Ružomberok, the original agricultural and current recreational function of the landscape could decline significantly. The only stable function of the landscape would remain in the form of forestry, which could be strengthened at the expense of the abandonment of agricultural land and forest expansion. Quality research needs to bring benefits not only in the theoretical and methodological area, but also in the application itself, in order for the results of research and evaluation to be used primarily in the planning and design area, as well as in the educational process. Knowledge of new qualitative indicators of the environment of rural settlements and knowledge of innovative methods of their evaluation will contribute to improving the overall quality of rural settlements, environmental protection, preserving ecological stability and diversity of the territory and rational use of natural and cultural-historical resources available to Slovak rural settlements. Thanks to the willingness of the current inhabitants, as well as their descendants, to preserve the historical biodiversity and landscape character, there is still the potential to preserve the genius loci of this site.

The results obtained so far show that by respecting the landscape ecological principles, the set of methodological procedures used allows us to manage the future care for the landscape of Vlkolínec. In this context, the information obtained becomes a significant contribution to its further development, management and planning.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.P., M.B. and I.T.; methodology, F.P., M.B. and I.T.; formal analysis, F.P., M.B., I.R., I.T. and E.P.; data curation, F.P.; writing—original draft preparation F.P., M.B., I.R., I.T. and E.P.; visualization, F.P., M.B., I.R., I.T. and E.P.; supervision, F.P., M.B. and E.P.; project administration, F.P. and M.B.; funding acquisition, M.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The results of this paper were elaborated within the projects: Vedecká Grantová Agentúra MŠVVaŠ SR a SAV: 2/0170/21: “Management of global change in vulnerable areas”, Vedecká Grantová Agentúra MŠVVaŠ SR a SAV: 1/0934/17 “Land-use changes of Slovak cultural landscape over the past 250 years and prediction of its further development”, Vedecká Grantová Agentúra MŠVVaŠ SR a SAV: 1/0658/19: “Ecosystem approaches to assessing of anthropogenic changed territories according to selected indicating groups of species”, VEGA 2/0077/21 “Integration of supply of selected ecosystem services for societal demand in terms of developing sustainable forms of tourism" and the Slovak Research and Development Agency under the Contract no. APVV-18-0185”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data used in this contribution are from public resources cited in the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Rössler, M. Rural Landscapes and Sustainable Development: International Day for Monuments and Sites 2019. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/news/1959 (accessed on 11 December 2020).

- Antrop, M. Sustainable landscapes: Contradiction, fiction or utopia? Landsc. Urban Plan. 2006, 75, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, J.A. Townships to Farmsteads: Rural Settlement Studies in Scotland, England and Wales; British Series: 293; British Archaeological Reports: Oxford, UK, 2000; p. 243. ISBN 1841711314. [Google Scholar]

- Picuno, P. Vernacular farm buildings in landscape planning: A typological analysis in a southern Italian region. J. Agric. Eng. 2012, 43, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Vaart, J.H.P. Towards a new rural landscape: Consequences of non-agricultural re-use of redundant farm buildings in Friesland. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2005, 70, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Sasso, P.; Caliandro, L.P. The role of historical agro-industrial buildings in the study of rural territory. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010, 96, 146–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, J.M.; Gallego, E.; García, A.I.; Ayuga, F. New uses for old traditional farm buildings: The case of the underground wine cellars in Spain. Land Use Policy 2010, 27, 738–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero, G.; Sasso, S.D.; Loisi, R.V.; Verdiani, G. Characteristics and distribution of trulli constructions in the area of the site of community importance Murgia of Trulli. J. Agric. Eng. 2013, 44, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirsop-Taylor, N.; Russel, D.; Winter, M. The Contours of State Retreat from Collaborative Environmental Governance under Austerity. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Han, B.; Wang, D.; Ouyang, Z. Ecological Wisdom and Inspiration Underlying the Planning and Construction of Ancient Human Settlements: Case Study of Hongcun UNESCO World Heritage Site in China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. World Heritage Site Designation Impacts on a Historic Village: A Case Study on Residents’ Perceptions of Hahoe Village (Korea). Sustainability 2016, 8, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullino, P.; Beccaro, G.L.; Larcher, F. Assessing and Monitoring the Sustainability in Rural World Heritage Sites. Sustainability 2015, 7, 14186–14210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antrop, M. Why Landscapes of the Past Are Important for the Future. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2005, 70, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoones, I. Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: A Framework for Analysis; IDS Working Paper 72; Institute of Development Studies (IDS): Brighton, UK, 1998; p. 22. [Google Scholar]

- Mansfeld, Y.; Jonas, A. Evaluating the socio-cultural carrying capacity of rural tourism communities: A ‘Value Stretch’ approach. TESG J. Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2006, 97, 583–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfeld, Y. Tourism, community and socio-cultural sustainability in Cultural Routes. In Cultural Routes Management: From Theory to Practice; Denu, P., Berti, E., Mariotti, A., Eds.; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2015; pp. 73–83. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, P.E. Tourism: A Community Approach (RLE Tourism); Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2013; p. 218. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, M.C. Progress in Tourism Management: Community Benefit Tourism Initiatives—A Conceptual Oxymoron? Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tromo, A.; Prete, M.I.; Napoli, J. Tourism Economy Related to Heritage. World Heritage: Socio-Economic Perspectives. In Tourism Management at UNESCO World Heritage Sites; Ascaniis, S., Gravari-Barbos, M., Contori, L., Eds.; Università della Svizzera italiana: Lugano, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 83–90. [Google Scholar]

- Sabolová, E. Selected impacts of tourism in region and theoretical basis of residents’ perception of tourism. Folia Geogr. 2013, 21, 119–128. [Google Scholar]

- De Kadt, E. Tourism—Passport to Development? Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1979; p. 360. [Google Scholar]

- Ap, J.; Crompton, J.L. Developing and testing tourism impact scale. J. Travel Res. 1998, 37, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inskeep, E. Tourism Planning—An Integrated and Sustainable Development Approach; Van Nostrand Reinhold: New York, NY, USA, 1991; p. 528. [Google Scholar]

- Gullino, P.; Larcher, F. Integrity in UNESCO World Heritage Sites. A comparative study for rural landscapes. J. Cult. Herit. 2013, 14, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ot’ahel’, J.; Feranec, J.; Kopecká, M.; Falt’an, V. Modification of the CORINE Land Cover method and the nomenclature for identification and inventorying of land cover classes at a scale of 1:10,000 based on case studies conducted in the territory of Slovakia. Geogr. Čas. 2017, 69, 189–224. [Google Scholar]

- Ot’ahel’, J.; Solár, V.; Matlovič, R.; Krokusová, J.; Pazúrová, Z.; Ivanová, M. Suburban landscape: Analyzes of manifestation of suburbanization in the hinterland of Prešov. Geogr. Čas. 2020, 72, 131–155. [Google Scholar]

- Kolejka, J. Landscape Mapping Using GIS and Google Earth Data. Geogr. Nat. Resour. 2018, 39, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skokanová, H.; Havlíček, M.; Klusáček, P.; Martinát, S. Five military training areas—Five different trajectories of land cover development? Case studies from the Czech Republic. Geogr. Cassoviensis 2017, 11, 201–213. [Google Scholar]

- Chrastina, P.; Trojan, J.; Župčan, L.; Tuska, T.; Hlásznik, P.P. Land use as a means of the landscape revitalisation: An example of the Slovak exploae of Tardoš (Hungary). Geogr. Cassoviensis 2019, 13, 121–140. [Google Scholar]

- Izakovičová, Z.; Miklós, L.; Miklósová, V. Integrative assessment of land use conflicts. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muchová, Z.; Raškovič, V. Fragmentation of land ownership in Slovakia: Evolution, context, analysis and possible solutions. Land Use Policy 2020, 95, 104644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muchová, Z.; Tárniková, M. Land cover change and its influence on the assessment of the ecological stability. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2018, 16, 2169–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pechanec, V.; Brus, J.; Kilianová, H.; Machar, I. Decision support tool for the evaluation of landscapes. Ecol. Inform. 2015, 30, 305–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilianová, H.; Pechanec, V.; Brus, J.; Kirchner, K.; Machar, I. Analysis of the development of land use in the Morava. River floodplain, with special emphasis on the landscape matrix. Morav. Geogr. Rep. 2017, 25, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jedlička, J.; Havlíček, M.; Dostál, I.; Huzlík, J.; Skokanová, H. Assessing relationships between land use changes and the development of a road network in the Hodonín region (Czech Republic). Quaest. Geogr. 2019, 38, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skokanová, H.; Netopil, P.; Havlíček, M.; Šarapatka, B. The role of traditional agricultural landscape structures in changes to green infrastructure connectivity. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2020, 302, 107071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlík, L.; Gábor, M.; Falt’an, V.; Lauko, V. Monitoring of vineyards utilization: Case study Modra (Slovakia). Geogr. Cassoviensis 2017, 11, 22–32. [Google Scholar]

- Slámová, M.; Belčáková, I. The Role of Small Farm Activities for the Sustainable Management of Agricultural Landscapes: Case Studies from Europe. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izakovičová, Z. Evaluation of the stress factors in the landscape. Ekológia 2000, 19, 92–103. [Google Scholar]

- Svrček, P.; Bišťan, M.; Dvorský, P. Vlkolínec, Krátka História, Architektúra a Život; Mesto Ružomberok: Ružomberok, Slovakia, 2008; p. 24. ISBN 978-80-969976-2-6. (In Slovak) [Google Scholar]

- Babál, M. Drevená Dedina Vlkolínec; Mestský Úrad: Ružomberok, Slovakia, 2002; p. 307. ISBN 80-966974-6-3. (In Slovak) [Google Scholar]

- Tomčíková, I.; Rakytová, I. Návrhy na podporu udržateľného cestovného ruchu v lokalite Vlkolínec. In Aktuální Problémy Cestovního Ruchu; Pachrová, S., Linderová, I., Doležalová, M., Eds.; Vysoká Školy Polytechnická Jihlava: Jihlava, Czech Republic, 2018; pp. 451–461. (In Slovak) [Google Scholar]

- Štefunková, D.; Dobrovodská, M. Kultúrno-historické zdroje Slovenska a ich význam pre trvalo udržateľný rozvoj. In Implementácia Trvalo Udržateľného Rozvoja; Izakovičová, Z., Kozová, M., Pauditšová, E., Eds.; Ústav Krajinnej Ekológie SAV pre SNK SCOPE: Smolenice, Slovakia, 1998; pp. 104–111. (In Slovak) [Google Scholar]

- Slamová, M.; Chudý, F.; Tomaštík, J.; Kardoš, M.; Modranský, J. Historical Terraces—current situation and future persectives for optimal land use management: The case study of Čierny Balog. Ann. Anal. Istrske Mediter. Stud. Ser. Hist. Sociol. 2019, 29, 85–100. [Google Scholar]

- Špulerová, J.; Dobrovodská, M.; Štefunková, D.; Piscová, V.; Petrovič, F. History of the Origin and Development of the Historical Structures of Traditional Agricultural Landscape. Hist. Čas. 2016, 64, 109–126. [Google Scholar]

- Slámová, M.; Belčáková, I. The vineyard landscapes. History and trends of viticulture in case studies from Slovakia|Los paisajes de viñedos. Historia y tendencias de la viticultura en casos de estudio de Eslovaquia. Pirineos 2020, 175, e056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hreško, J.; Petrovič, F.; Mišovičová, R. Mountain landscape archetypes of the Western Carpathians (Slovakia). Biodivers. Conserv. 2015, 24, 3269–3283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochel, B. Obnova senníkov v lokalite UNESCO Vlkolínec. In Zborník z Konferencie: 25. Výročie Zápisu Lokality Vlkolínec do Zoznamu Svetového Dedičstva UNESCO; Katolícka univerzita v Ružomberku: Ružomberok, Slovakia, 2018; pp. 75–81. (In Slovak) [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M.; Piggin, R. Tourism and world heritage in OECD countries. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2001, 26, 103–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, J.; Silvano, S. World heritage sites: The purposes and politics of destination branding. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2010, 27, 533–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parga-Dans, E.; González, P.A.; Enríquez, R.O. The social value of heritage: Balancing the promotion-preservation relationship in the Altamira World Heritage Site, Spain. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 18, 100499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullino, P.; Pomatto, E.; Gaino, W.; Devecchi, M.; Larcher, F. New challenges for historic gardens’ restoration: A holistic approach for the royal park of moncalieri castle (turin metropolitan area, Italy). Sustainability 2020, 12, 10067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, P. Ecomuseums and the Democratisation of Japanese Museology. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2004, 10, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devecchi, M. Production innovation and environmental protection in the management of rural landscapes: The UNESCO vineyard landscapes of Langhe-Roero and Monferrato. E3S Web Conf. 2019, 119, 00014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnoletti, M.; Tredici, M.; Santoro, A. Biocultural diversity and landscape patterns in three historical rural areas of Morocco, Cuba and Italy. Biodivers. Conserv. 2015, 24, 3387–3404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yotsumoto, Y.; Vafadari, K. Comparing cultural world heritage sites and globally important agricultural heritage systems and their potential for tourism. J. Herit. Tour. 2020, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocks, M.; Vetter, S.; Wiersum, K.F. From universal to local: Perspectives on cultural landscape heritage in South Africa. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2018, 24, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandarin, F.; van Oers, R. The Historic Urban Landscape: Managing Heritage in an Urban Century, 1st ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; p. 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angrisano, M.; Biancamano, P.F.; Bosone, M.; Carone, P.; Daldanise, G.; De Rosa, F.; Franciosa, A.; Gravagnuolo, A.; Iodice, S.; Nocca, F.; et al. Towards operationalizing UNESCO Recommendations on “Historic Urban Landscape”: A position paper. Aestium 2016, 69, 165–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindholm, K.J.; Ekblom, A. A framework for exploring and managing biocultural heritage. Anthropocene 2019, 25, 100195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Montis, A. Impacts of the European Landscape Convention on national planning systems: A comparative investigation of six case studies. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 124, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linkola, H. Administration, landscape and authorized heritage discourse—Contextualising the nationally valuable landscape areas of Finland. Landsc. Res. 2015, 40, 939–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, M. Policy change and ELC implementation: Establelishment of a baseline for understanding the impact on UK national policy of the European Landscape Convention. Landsc. Res. 2013, 38, 768–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandström, U.; Hedfors, P. Uses of the word ‘landskap’ in Swedish municipalities’ comprehensive plans: Does the European Landscape Convention require a modified understanding? Land Use Policy 2018, 70, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la, O.; Cabrera, M.R.; Marine, N.; Escudero, D. Spatialities of cultural landscapes: Towards a unified vision of Spanish practices within the European Landscape Convention. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2020, 28, 1877–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrić, L.; Hell, M.; van der Borg, J. Process orientation of the world heritage city management system. J. Cult. Herit. 2020, 46, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackleton, R.T.; Bertzky, B.; Wood, L.E.; Bunbury, N.; Jäger, H.; Van Merm, R.; Sevilla, C.; Smith, K.; Wilson, J.R.U.; Witt, A.B.R.; et al. Biological invasions in World Heritage Sites: Current status and a proposed monitoring and reporting framework. Biodivers. Conserv. 2020, 29, 3327–3347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olah, B. Potential for the sustainable land use of the cultural landscape based on its historical use (A model study of the transition zone of the Pol’ana Biosphere Reserve). Ekol. Bratisl. 2003, 22, 79–91. [Google Scholar]

- Vilbig, J.M.; Sagan, V.; Bodine, C. Archaeological surveying with airborne LiDAR and UAV photogrammetry: A comparative analysis at Cahokia Mounds. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2020, 33, 102509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanová, M.; Michaeli, E.; Boltižiar, M.; Fazekašová, D. The analysis of changes ecological stability of landscape in the contrasting region of the mountain range and a lowland. In Ecology, Economics, Education and Legislation, Proceedings of the 13th Internatio-nal Multidisciplinary Scientific Geoconference SGEM, Albena, Bulgaria, 16–22 June 2013; SGEM: Albena, Bulgaria, 2013; pp. 925–938. [Google Scholar]

- Druga, M.; Falťan, V.; Herichová, M. Návrh modifikácie metodiky CORINE Land Cover pre účely mapovania historických zmien krajinnej pokrývky na území Slovenska v mierke 1:10,000—príkladová štúdia historického k.ú. Batizovce (The proposal of the modification of the CORINE Land Cover nomenclature for the purpose of historical land cover change mapping in the territory of Slovakia in the scale 1:10,000—case study of historical cadastral area of Batizovce). Geogr. Cassoviensis 2015, 9, 7–34. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, N.; Tiwari, P.S.; Pande, H.; Agrawal, S. Utilizing Advance Texture Features for Rapid Damage Detection of Built Heritage Using High-Resolution Space Borne Data: A Case Study of UNESCO Heritage Site at Bagan, Myanmar. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 2020, 48, 1627–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olah, B.; Žigrai, F. The meaning of the time-spatial transformation of the landscape for its sustainable use (A case study of the transition zone of the Pol’ana Biosphere Reserve). Ekol. Bratisl. 2004, 23, 231–243. [Google Scholar]

- Falťan, V.; Saksa, M. Zmeny krajinnej pokrývky okolia Štrbského plesa po veternej kalamite v novembri 2004 (Land cover changes in the environs of Štrbské pleso after the wind disaster of November 2004). Geogr. Čas. 2007, 59, 359–372. [Google Scholar]

- Katelieva, M.; Muhar, A.; Penker, M. Nature-related knowledge as intangible cultural heritage: Safeguarding and tourism utilisation in Austria. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2020, 18, 673–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larraz, B.; García-Gómez, E. Depopulation of Toledo’s historical center in Spain? Challenge for local politics in world heritage cities. Cities 2020, 105, 102841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Park, C.; Kim, M. Tourism Destination Management Strategy for Young Children: Willingness to Pay for Child-Friendly Tourism Facilities and Services at a Heritage Site. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudáš, M. Pamiatková rezervácia ľudovej architektúry Vlkolínec v Zozname svetového dedičstva UNESCO (in Slovak). In Zborník z Konferencie: 25. Výročie Zápisu Lokality Vlkolínec do Zoznamu Svetového Dedičstva UNESCO; Katolícka univerzita v Ružomberku: Ružomberok, Slovakia, 2018; pp. 32–50. [Google Scholar]

- Boltižiar, M.; Petrovič, F. Zhodnotenie potenciálu historických fotografií, máp a leteckých snímok pre štúdium zmien kultúrnej krajiny na príklade lokality UNESCO—Vlkolínec (Slovensko). In Zborník z Konferencie: 25. Výročie Zápisu Lokality Vlkolínec do Zoznamu Svetového Dedičstva UNESCO; Katolícka univerzita v Ružomberku: Ružomberok, Slovakia, 2018; pp. 51–66. (In Slovak) [Google Scholar]

- Pauditšová, E.; Kozová, M.; Petrovič, F.; Piteková, J.; Rakytová, I.; Šalkovič, M.; Šlávka, M.; Tomčíková, I.; Papčo, P.; Vantara, P.; et al. Krajinná Štúdia—Vlkolínec; Verbum: Ružomberok, Slovakia, 2019; p. 101. ISBN 978-80-561-0668-6. (In Slovak) [Google Scholar]

| Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).